4.1. Hypothesis Validation: Accuracy vs. Computational Efficiency Trade-Off

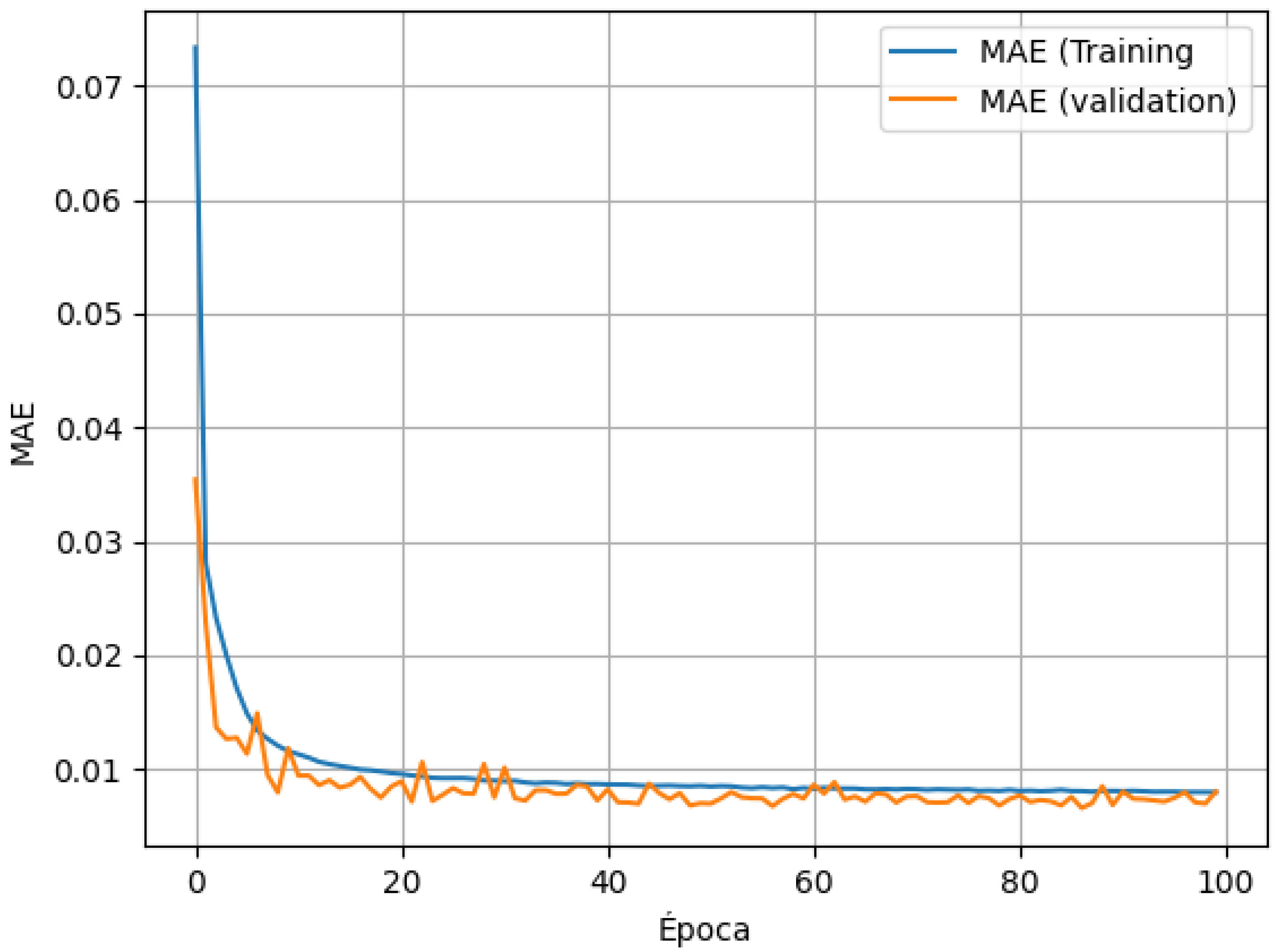

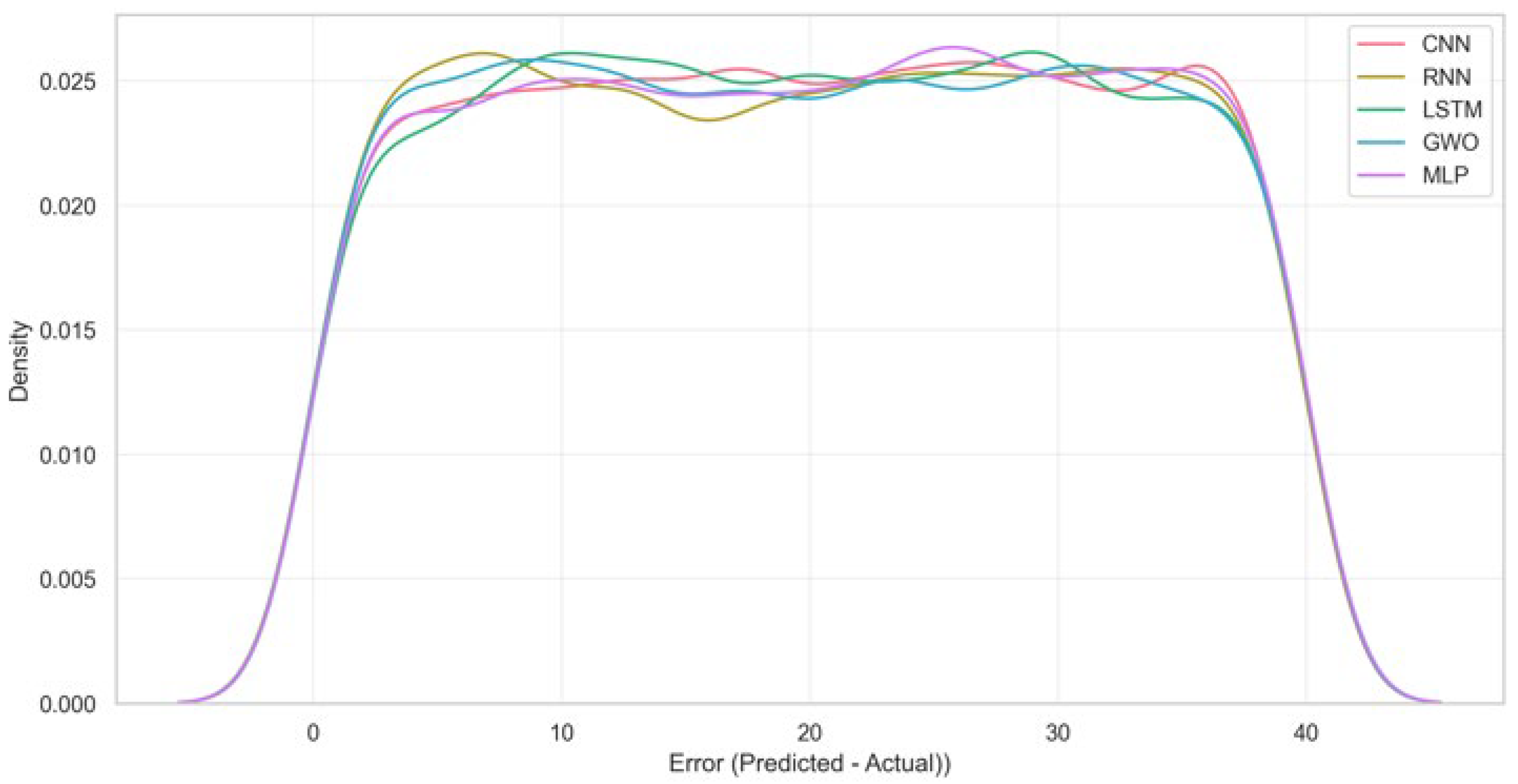

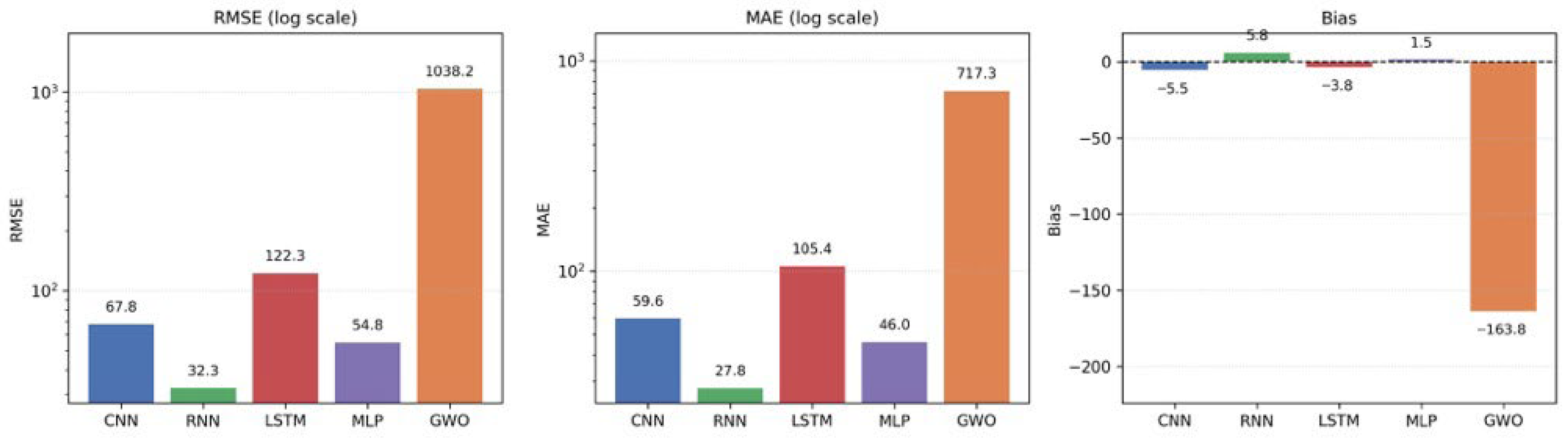

The results show that under the present experimental setting, simpler neural architectures such as MLP and RNN can match or even outperform more complex models such as LSTM and CNN while requiring substantially lower computational resources. Among all of the evaluated models, the RNN achieved the highest predictive accuracy (RMSE ≈ 32.3, MAE ≈ 27.8, R

2 ≈ 0.96), and the MLP also exhibited competitive performance (R

2 ≈ 0.88). In contrast, the LSTM and CNN presented higher error levels (R

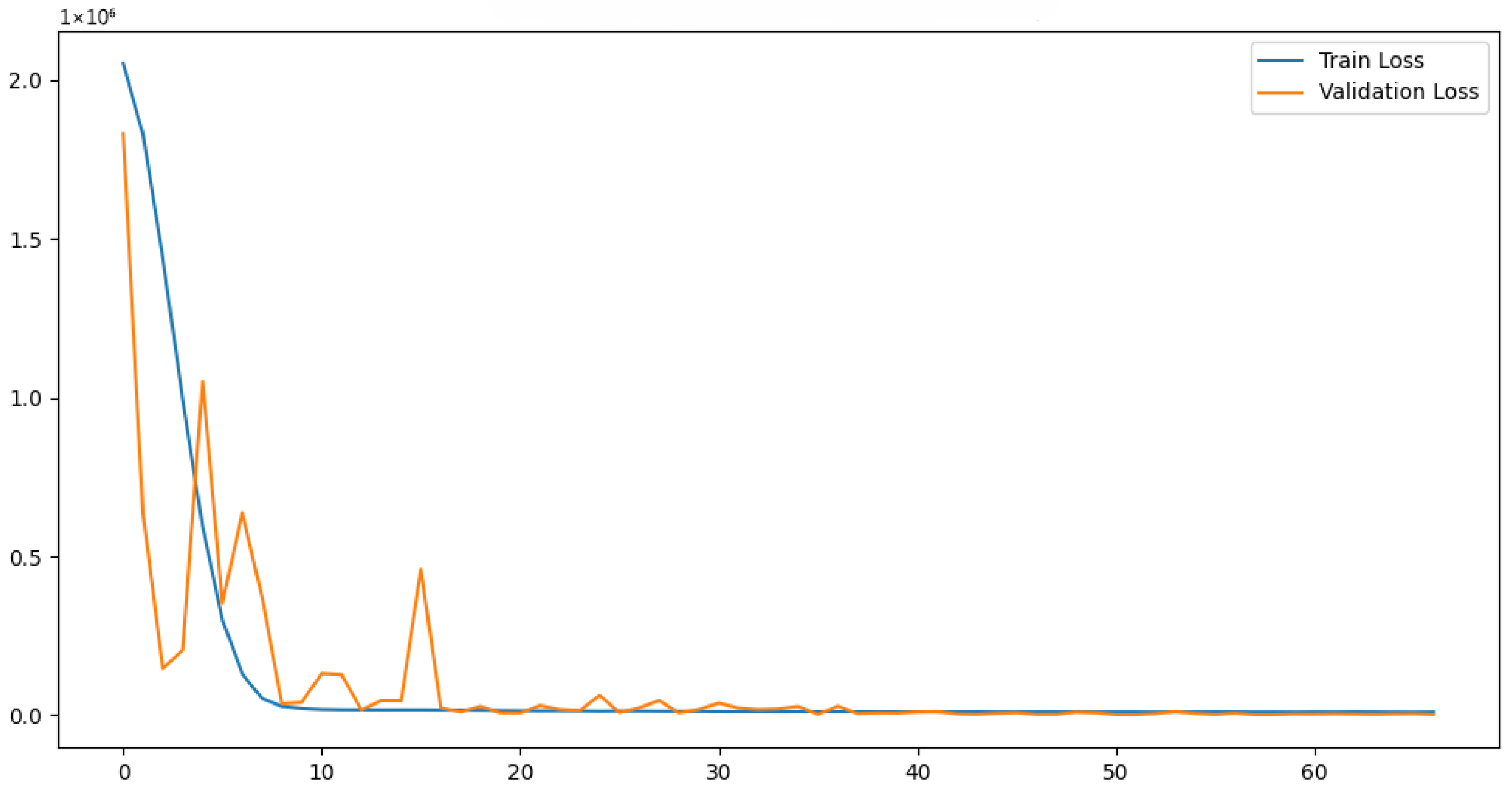

2 ≈ 0.39 and 0.81, respectively), despite their greater architectural complexity. The LSTM, in particular, displayed clear signs of overfitting, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

The comparatively low performance of the LSTM relative to the simpler RNN, despite both models being trained with the same 30-day input window, suggests sensitivity to training configuration rather than an intrinsic limitation of gated recurrent units. In spatiotemporal regression problems characterized by extremely high-dimensional output spaces (10,965 outputs), LSTM architectures can become more difficult to optimize and are more susceptible to over-parameterization under limited regularization. Although vanishing or exploding gradients were not explicitly diagnosed, the observed training instability and divergence between training and validation errors are consistent with gradient sensitivity issues commonly reported in deep recurrent architectures operating under high-dimensional output constraints.

Within the unified training protocol adopted in this study, the LSTM consistently exhibited poorer validation behavior than the RNN. This outcome is compatible with several non-exclusive factors, including suboptimal learning-rate dynamics, insufficient regularization relative to model capacity, and a potential mismatch between the fixed 30-day temporal window and the effective temporal dependencies governing daily GHI fields. These observations motivate future controlled experiments incorporating gradient clipping, alternative learning-rate schedules, and different look-back windows to assess whether LSTM performance can be recovered under a more carefully tuned regime. Similar behavior has been reported in previous studies, where well-tuned simpler architectures matched or outperformed more complex models in daily forecasting tasks [

17,

19].

From a computational perspective, both the RNN and MLP achieved their predictive skill with substantially lower training time and GPU memory consumption than the LSTM and the MLP–GWO, as detailed in

Section 2.4. This favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency makes these simpler architectures particularly attractive for operational or resource-constrained environments [

17,

19,

30].

Regarding Hypothesis H2, the results indicate that incorporating the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) to tune the MLP did not provide performance gains sufficient to offset the additional computational cost. The MLP–GWO model produced unrealistic predictions, with extremely large errors (RMSE ≈ 1038.2) and a highly negative coefficient of determination (R

2 ≈ −43.2;

Table 3 and

Table 4). Quantitatively, while the baseline MLP achieved an RMSE ≈ 54.8, MAE ≈ 46.0, and R

2 ≈ 0.88, the MLP–GWO configuration yielded an RMSE ≈ 1038.2, MAE ≈ 717.3, and R

2 ≈ −43.2, together with very large P95 errors (≈ 2421.4 kWh·m

−2·day

−1) and infinite Jensen–Shannon divergence (

Table 3 and

Table 4). These metrics demonstrate that under the present configuration, the parameter sets selected by the GWO led to predictions that were statistically incompatible with the ERA5-based reference distribution.

It is important to explicitly acknowledge that no dedicated diagnostic analyses of the GWO optimization process were performed in this study. In particular, convergence trajectories, sensitivity to population size, and sensitivity to the number of iterations were not systematically evaluated. The reported results therefore correspond to a representative, but not exhaustive, configuration of the metaheuristic search. For reproducibility, the final GWO-selected setup consisted of 384 and 192 neurons in the first and second hidden layers, respectively, a dropout rate of 0.28, and a learning rate of 4.2 × 10−3, with a population of 20 individuals evolved over 30 iterations using validation MAE as the fitness metric.

Under this specific experimental configuration—characterized by an extremely high-dimensional output space (10,965 grid points), spatially aggregated error metrics acting as a noisy fitness signal, and a limited search budget—the use of a population-based, gradient-free optimizer to tune the MLP yielded no practical performance advantages over standard gradient-based training. However, these findings should not be interpreted as a general limitation of the Grey Wolf Optimizer or of metaheuristic optimization methods as a class [

5,

31], but rather as an outcome that is conditional on the constraints and design choices of the present study.

Regarding temporal context, the recurrent models (RNN and LSTM) were trained using a 30-day input window, whereas the MLP and 1D-CNN relied on single-day inputs, following common practice in daily atmospheric forecasting. Since the LSTM did not outperform the RNN even under identical input-window conditions, the observed performance differences can more plausibly be attributed to differences in model stability and optimization behavior rather than to input length alone. A sensitivity analysis conducted for the RNN using 7-, 15-, and 30-day input windows showed progressively improved performance with increasing window length, which saturated around 30 days, suggesting diminishing returns. This behavior indicates that the RNN’s predictive skill arises from capturing sub-seasonal temporal patterns rather than simply from increased historical input.

Overall, the limitations identified for the MLP–GWO configuration are strictly conditional on the present experimental setup, including the ERA5-driven predictors, the specific MLP architecture summarized in

Table 2, and the GWO hyperparameter ranges described in

Section 2.5.1. Consequently, while gradient-based optimization remains more reliable and efficient than the tested GWO configuration for this particular high-dimensional daily solar forecasting task, broader conclusions regarding metaheuristic optimization require further targeted investigation beyond the scope of this study.

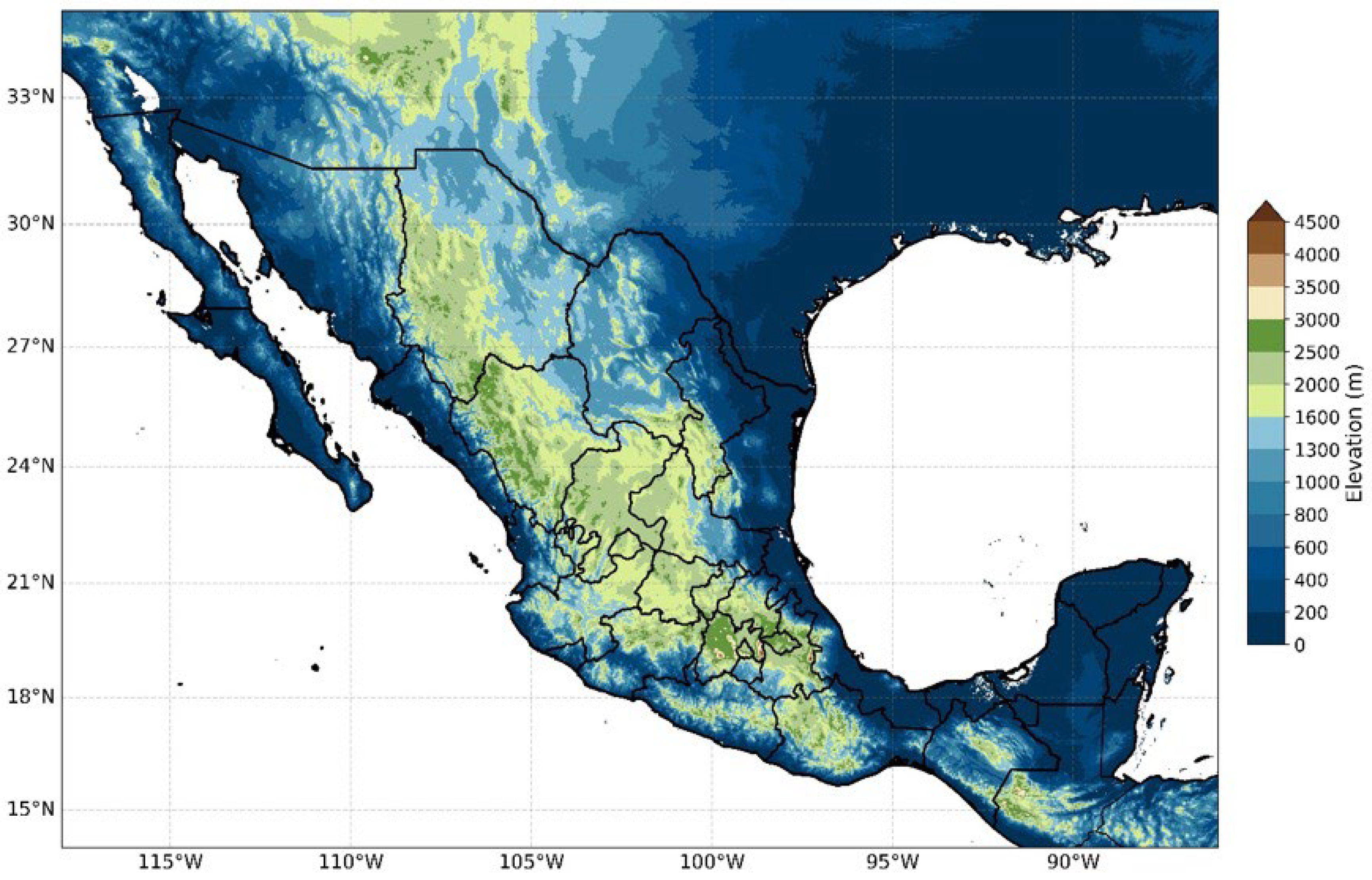

4.2. Spatial Fidelity: Emulation of ERA5 Patterns and Topographic Limitations

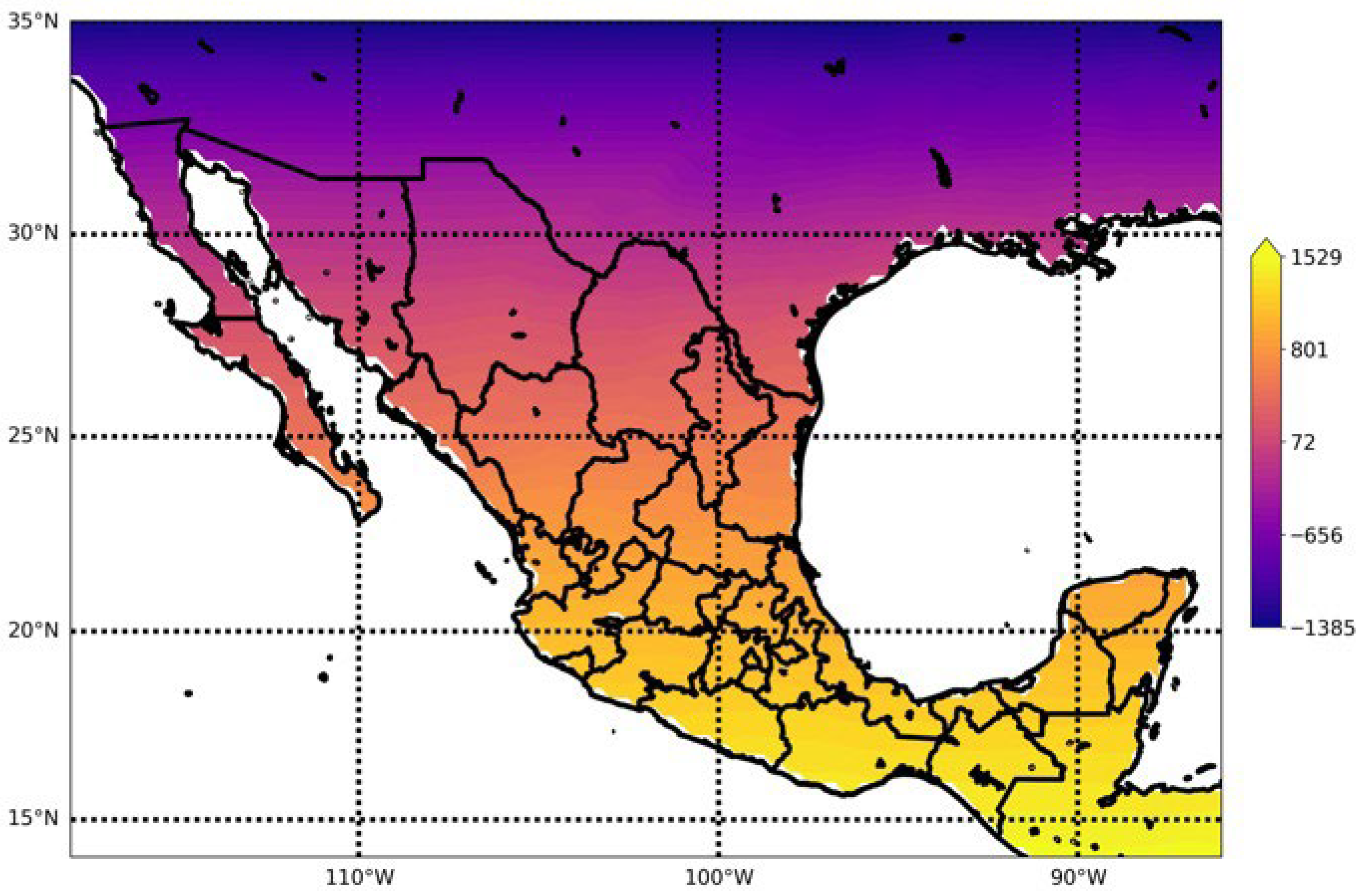

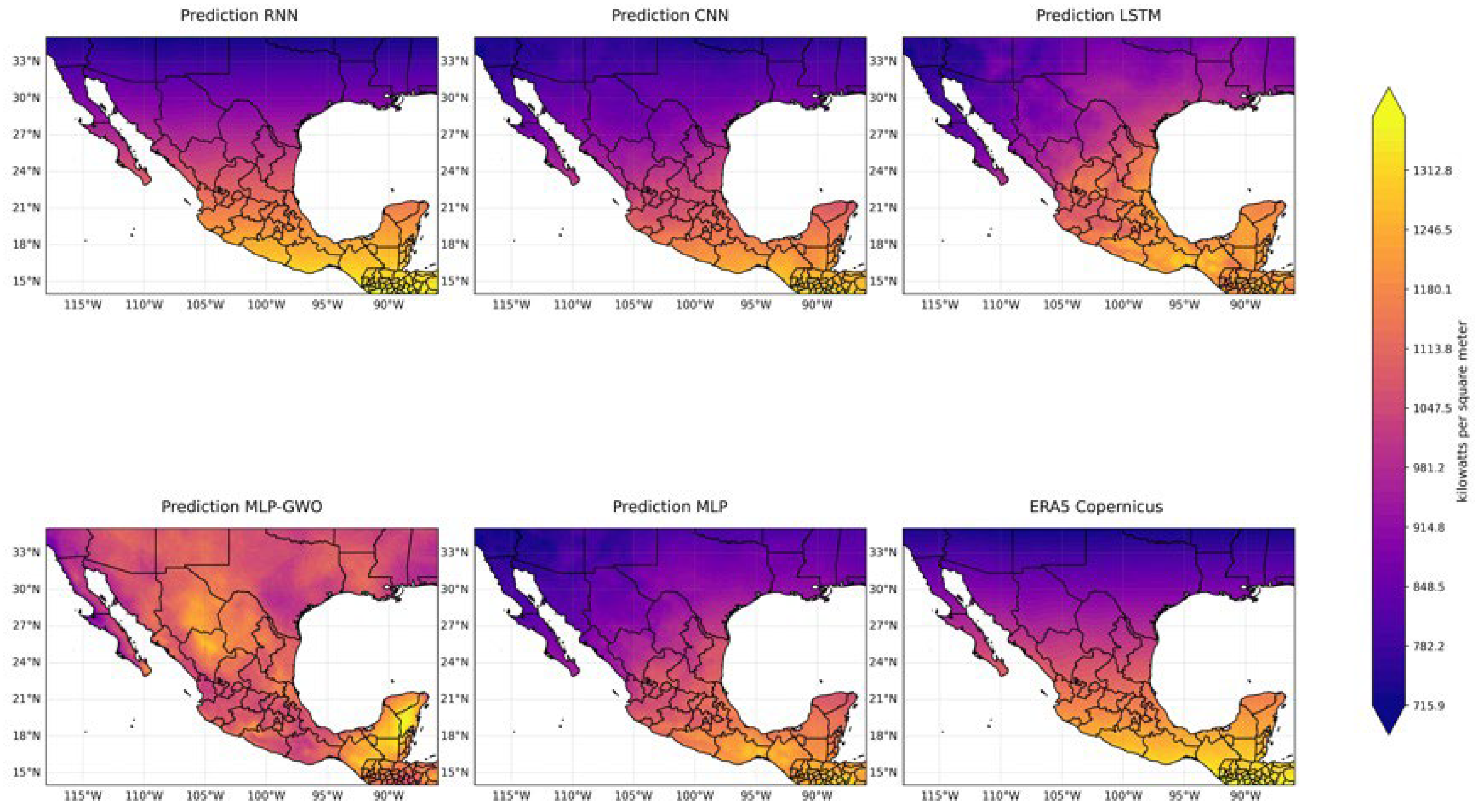

The spatial prediction maps (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) complement the statistical evaluation by illustrating how effectively the different models reproduce the large-scale spatial structure of ERA5-based solar potential over Mexico. Rather than aiming at fine-scale spatial downscaling, the evaluated architectures are explicitly designed to function as fast spatial surrogates of ERA5 climatology under constrained computational resources, consistent with the lightweight modeling objective of this study.

The RNN and MLP models successfully reconstructed the dominant spatial gradients of daily solar potential across the Mexican domain. These include the high-irradiance plateaus over northern Mexico, reduced values in the more humid southeastern regions, and broad modulations associated with major orographic features such as the Sierra Madre Occidental. This behavior indicates that even relatively lightweight architectures are capable of learning the nonlinear mapping between coarse-scale atmospheric predictors and surface solar radiation fields at the ERA5 spatial scale, including over topographically complex regions [

26].

Importantly, the reproduced patterns correspond to the large-scale climatological structure represented in ERA5, rather than to localized fine-scale variability. This is consistent with the intended role of the models as statistical emulators of reanalysis fields rather than as downscaling tools.

The spatial distribution of prediction errors is structured rather than random. The largest discrepancies relative to ERA5 were concentrated in regions where the reanalysis itself is known to exhibit higher uncertainty, particularly areas characterized by complex terrain and persistent cloud cover, such as southern Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico region [

6,

9]. This suggests that the models largely inherit the spatial smoothness and limitations of the ERA5 product, rather than correcting its known biases.

The localized noise and artifacts observed in the CNN and LSTM spatial maps (

Figure 8) further support this interpretation. These patterns indicate that the networks primarily learn and reproduce the ERA5 spatial climatology at its native ~0.25° resolution, including its smoothing behavior, instead of generating physically sharper gradients or performing implicit statistical downscaling [

11].

As anticipated in

Section 2.5.1, the relatively weaker performance of the 1D-CNN compared to the RNN is largely attributable to the adopted data representation rather than to an intrinsic limitation of convolutional modeling. In this study, the spatial grid was intentionally flattened into a one-dimensional index, thereby removing explicit two-dimensional latitude–longitude neighborhood relationships. This design choice was made to enforce architectural comparability across model families and to keep memory usage and training time within the hardware constraints defined by Hypotheses H1 and H2.

Under this representation, one-dimensional convolutional filters operate along a linearized feature sequence that lacks physical spatial adjacency. As a result, the CNN is inherently constrained in its ability to extract coherent spatial features that depend on local two-dimensional neighborhoods. The noisier and less spatially coherent CNN forecasts observed in regions of complex topography (

Figure 8) therefore reflect a loss of spatial topology rather than a fundamental shortcoming of convolutional approaches.

Two-dimensional convolutional architectures that preserve spatial adjacency would be better suited to capturing such features; however, their substantially higher memory and computational requirements place them outside the scope of the proposed lightweight framework and the resource constraints considered in this work.

These findings indicate that 1D-CNNs applied to flattened geophysical fields offer limited advantages when strict computational constraints are imposed. While more expressive convolutional architectures may yield improved spatial coherence if spatial structure is preserved and hardware limitations are relaxed, such configurations fell beyond the objectives of this study.

Accordingly, the comparatively weaker and noisier performance of the 1D-CNN should not be interpreted as evidence against convolutional modeling for solar radiation forecasting in general. Instead, it is a direct consequence of the intentionally simplified spatial representation and strict computational constraints adopted here. Under representations that preserve two-dimensional spatial adjacency—such as lightweight 2D CNNs or patch-based convolutional schemes—convolutional architectures would be expected to demonstrate stronger spatial coherence, but at the cost of increased memory usage and training time.

Overall, the proposed models should be interpreted as efficient and statistically consistent emulations of ERA5-based solar potential rather than as high-resolution spatial reconstructions. They are therefore best interpreted as being suitable for applications where ERA5-level accuracy is sufficient, including regional solar resource assessment, preliminary site screening, and system-level energy modeling requiring spatially complete daily inputs [

6,

32].

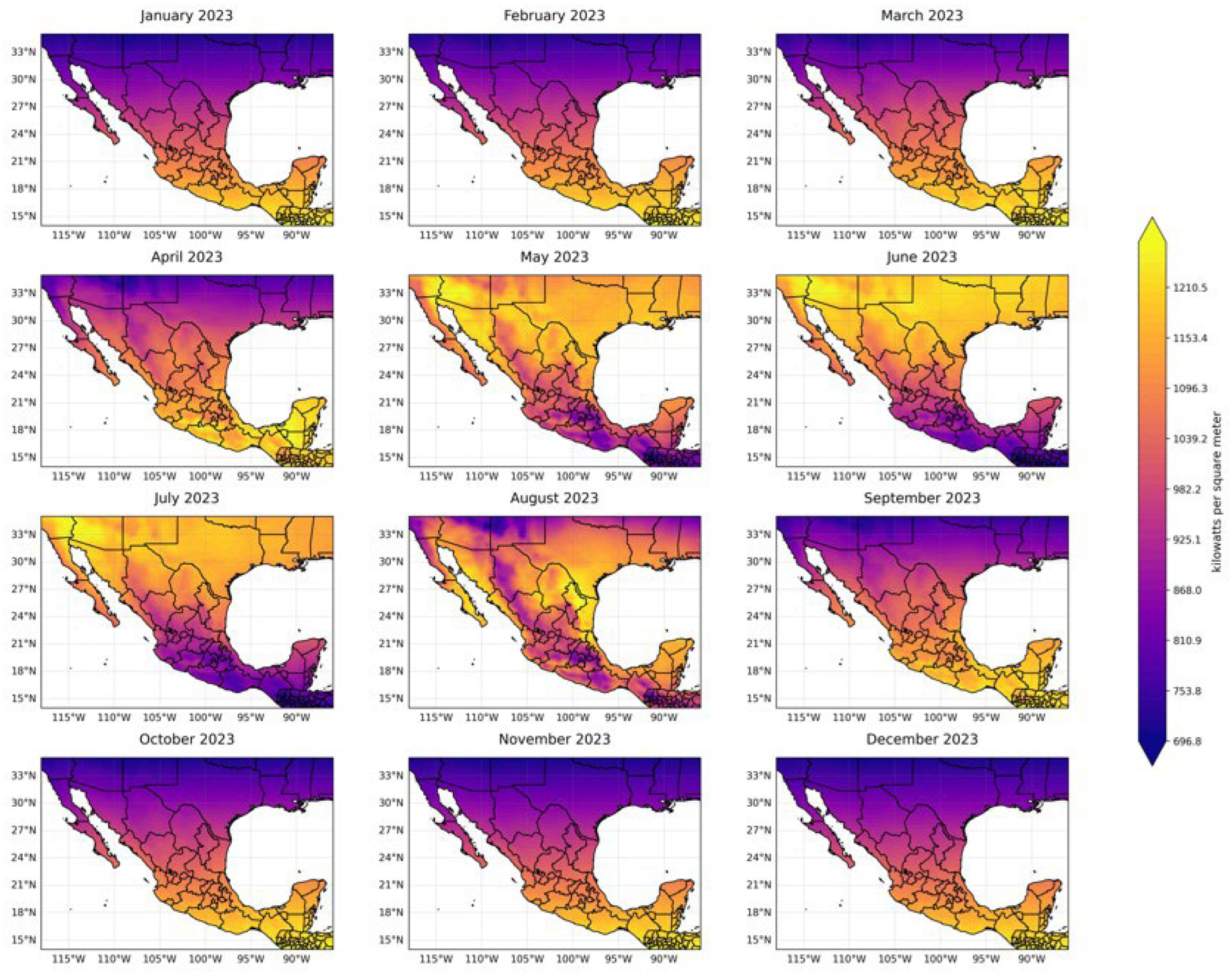

4.3. Sub-Regional and Seasonal Error Analysis

To better understand the overall performance, we examined how prediction errors changed by region and season in Mexico. We aimed to find patterns in model performance related to climate zones and seasonal weather, rather than provide detailed local validation.

We divided Mexico into broad regions based on climate and terrain: northern arid areas, the central highlands with complex terrain, and southern humid regions. All models had the lowest errors in northern Mexico, where clear skies are common. In the central and southern regions, errors were higher, likely due to complex terrain, frequent clouds, and more uncertainty in ERA5 surface radiation estimates [

6,

9]. The RNN and MLP models performed steadily across regions, while the 1D-CNN model showed more performance loss in complex terrain.

When we compared different seasons, we saw that the prediction errors changed with the weather. Errors were lowest during the dry season (DJF–MAM), when large-scale weather patterns, which ERA5 models well, control solar radiation. In the summer rainy season (JJA), all models had higher errors due to more clouds and greater small-scale weather changes. Despite these seasonal shifts, the RNN and MLP models still outperformed the more complex models.

In summary, these results show that lightweight models perform well across different regions and seasons, although they still have ERA5’s known limits in areas and times with many small-scale weather changes. This suggests that they constitute a viable option for regional studies where efficiency and broad coverage are prioritized over fine-scale local accuracy, where efficiency and broad coverage are more important than very detailed local accuracy [

6,

32].

4.4. Evaluation Against Ground-Based Radiometric Stations (CONAGUA/SMN)

To evaluate predictive skill beyond the ERA5 benchmark, we used available ground-based daily global horizontal irradiance (GHI) observations from stations operated by the Mexican National Meteorological Service (SMN–CONAGUA) over the 2020–2025 test period. These observations provide an independent, real-world reference for assessing the absolute performance of the proposed surrogate models.

We compared five surrogate models (MLP, RNN, LSTM, 1D-CNN, and MLP–GWO). For each station and day, model predictions were extracted from the nearest ERA5 grid cell (0.25° × 0.25°), and daily absolute errors were computed against the corresponding observed daily GHI values. No spatial interpolation or statistical bias correction was applied. Accordingly, this evaluation does not aim to correct systematic ERA5 biases, but rather to provide an indicative assessment of model skill under realistic observational constraints.

This comparison inherently involves a scale mismatch between point-based measurements and grid-cell average estimates. Previous studies have shown that such representativeness differences introduce unavoidable discrepancies, particularly in regions characterized by complex topography, coastal transitions, and convective cloud regimes. Consequently, the station-based evaluation should be interpreted as a broad indicator of real-world performance rather than a strict point-scale validation.

Across the SMN–CONAGUA stations, the RNN and MLP models exhibited the lowest errors and minimal bias, consistent with their strong performance in the ERA5-based validation. The LSTM model showed comparable but slightly weaker performance. The 1D-CNN yielded higher errors, likely reflecting its inability to preserve two-dimensional spatial relationships when operating on flattened spatial fields. The MLP–GWO model performed substantially worse, indicating that its metaheuristic optimization strategy does not generalize well when confronted with observational data.

Despite these limitations, the results indicate that the proposed lightweight models preserve strong daily temporal coherence and achieve error levels comparable to those reported in previous ERA5–station validation studies in the literature [

33]. This supports their potential applicability in practical contexts such as regional solar resource assessment, preliminary site screening, and system-level energy modeling, where ERA5-level accuracy is generally sufficient (

Table 5).

4.6. Consistency with ERA5 and Implications for Fast Surrogate Modeling

In summary, the findings of this study support a practical and context-specific approach for deploying lightweight neural network models as fast and computationally efficient surrogates of ERA5-derived daily solar potential, under constrained hardware and operational conditions. Rather than aiming to replace physical reanalysis systems, the proposed framework provides a statistically consistent emulation of ERA5 solar potential fields at the native spatial and temporal scales resolved by the reanalysis, enabling accessible energy analytics within clearly defined computational and methodological limits.

- 1.

Model Selection and Training (Offline Phase).

Within the specific experimental configuration evaluated in this study—namely daily-resolution forecasting driven exclusively by ERA5 predictors and trained under the hardware constraints described in

Section 2.4—the results indicate that an RNN offers the most favorable balance between predictive accuracy, convergence stability, and computational cost. An MLP represents a viable alternative when simplicity and minimal training overhead are prioritized. In both cases, the models are trained once using long-term ERA5 data on affordable consumer-grade hardware, after which no further retraining is required for routine deployment.

- 2.

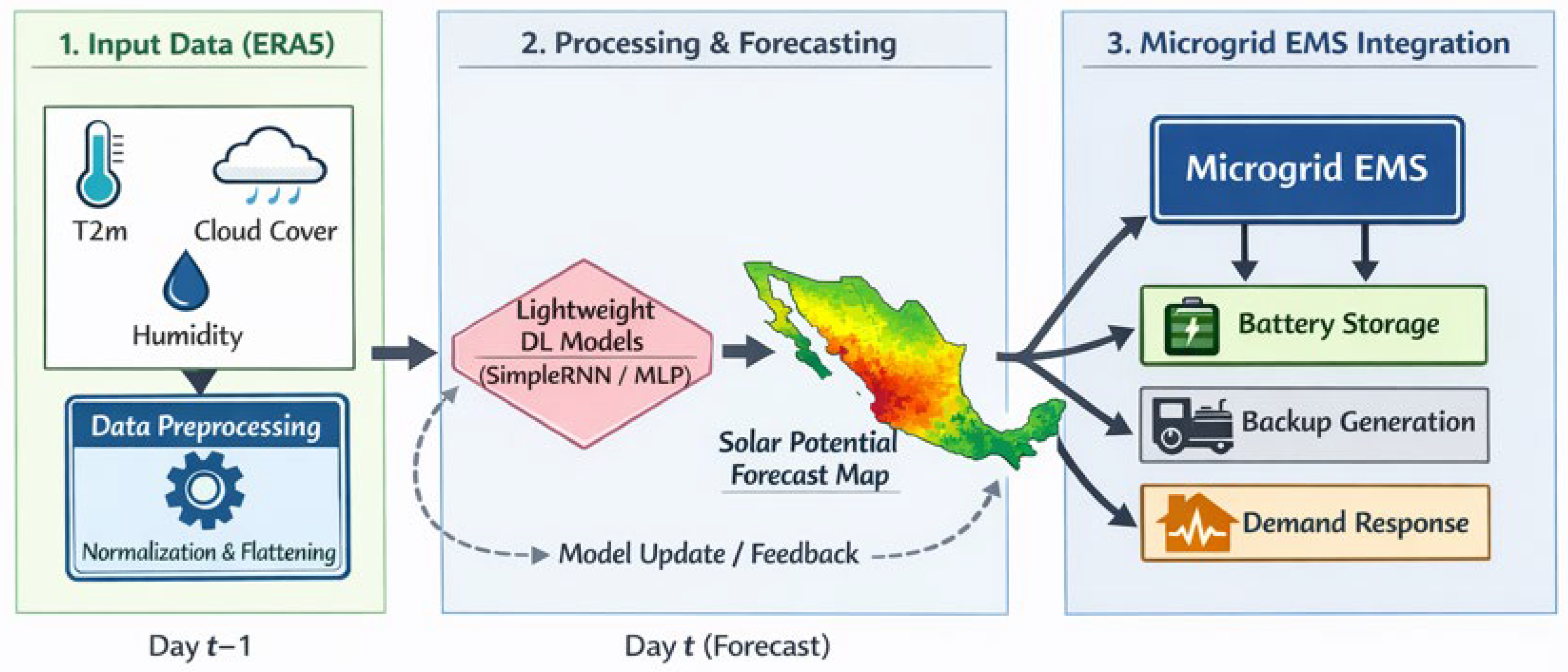

Integration and Deployment (Operational Phase).

Once trained, the selected model can be deployed as a lightweight, standalone forecasting module. Its inputs consist of preprocessed meteorological variables from the previous day (t − 1), obtained either from ERA5 near-real-time products or from regional numerical weather prediction outputs with comparable structure. The model output is a complete spatial map of predicted daily solar potential Ps(t) for day t, expressed on the ERA5 grid and fully consistent with its spatial resolution.

- 3.

Application in Energy Management Systems.

The resulting daily solar potential maps can be integrated into existing energy analysis workflows in several ways, including:

- (a)

As inputs to photovoltaic performance simulation tools for estimating the expected generation from existing or planned installations;

- (b)

As data layers for Smart Microgrid Energy Management Systems (EMSs) [

3,

34], supporting day-ahead scheduling of storage systems and dispatchable generation—core functions of intelligent energy systems [

27].

In all cases, the forecasts should be interpreted as ERA5-consistent inputs intended for planning and operational screening rather than as high-fidelity ground-truth estimates.

- 4.

Practical Deployment and Sustainability Considerations.

- (a)

Accessibility and operational resilience: By substantially reducing computational requirements, the proposed framework demonstrates a pathway to enable advanced solar forecasting capabilities in regions where high-performance computing resources are unavailable. This potential enhances access to spatially complete solar potential information for local planners and energy operators, particularly in emerging economies [

35].

- (b)

Computational and environmental efficiency: The use of lightweight models trained once and executed efficiently reduces long-term computational and energy costs relative to continuous high-resolution simulations or large deep learning architectures. This represents a step toward more sustainable data-driven practices in energy and climate analytics, by prioritizing computational efficiency [

34,

35].

- (c)

Scope and limitations: The proposed framework is designed to support—rather than replace—human decision-making. It accelerates the generation of daily, ERA5-consistent solar potential estimates over large areas and integrates naturally into existing planning pipelines. Its primary objective is to provide affordable, scalable decision support at the reanalysis scale, rather than localized bias correction, statistical downscaling, or real-time control [

25,

36,

37].

Taken together, the results demonstrate that within the specific ERA5-based, daily-resolution, and resource-constrained experimental framework considered in this study, lightweight neural models—particularly RNNs and MLPs—can function as efficient and statistically consistent surrogates of ERA5-derived daily solar potential fields. This consistency holds at the spatial and temporal scales resolved by the reanalysis itself, including regions of complex topography, where the models primarily reproduce large-scale ERA5 climatological patterns rather than correcting known reanalysis uncertainties. Consequently, the results suggest that these models are well-suited for large-scale, preliminary energy planning applications where ERA5-level spatial fidelity is sufficient and computational efficiency is a primary constraint [

38].