Ex Situ Sediment Remediation Using the Electrokinetic (EK) Two-Anode Technique (TAT) Supported by Mathematical Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sediment Sample

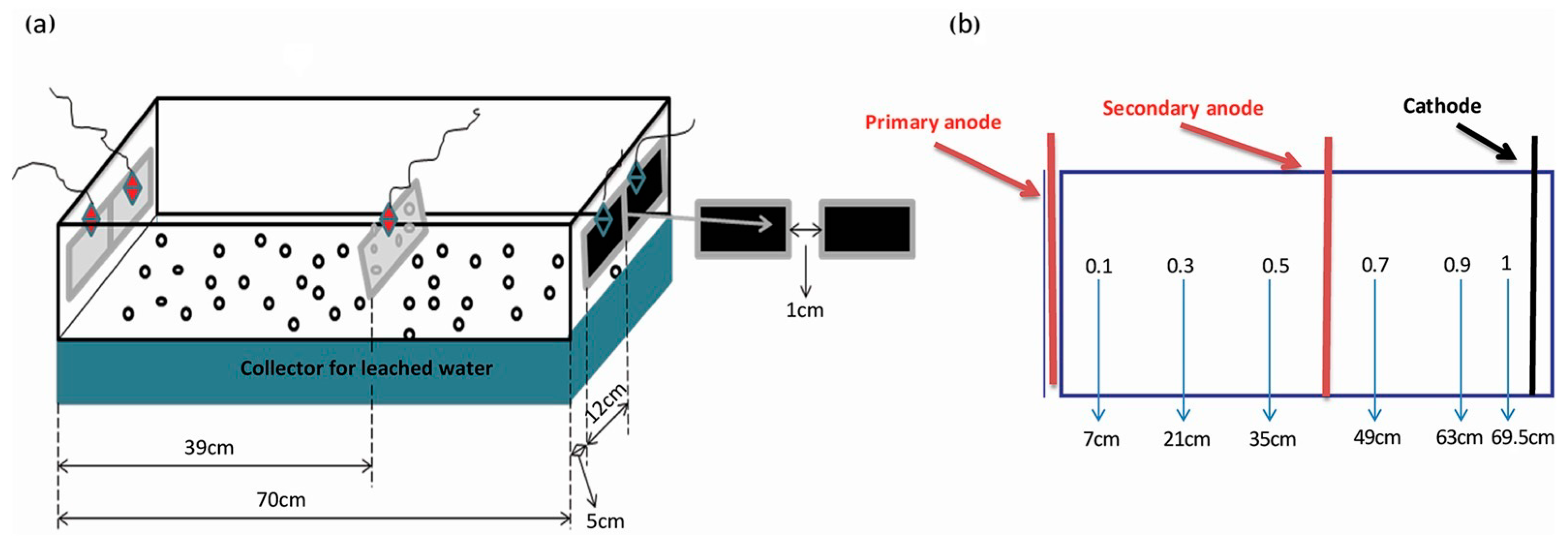

2.2. Electrokinetic Device

2.3. Chemicals and Analytical Methods

2.4. Mathematical Model and Simulation Procedure

3. Results

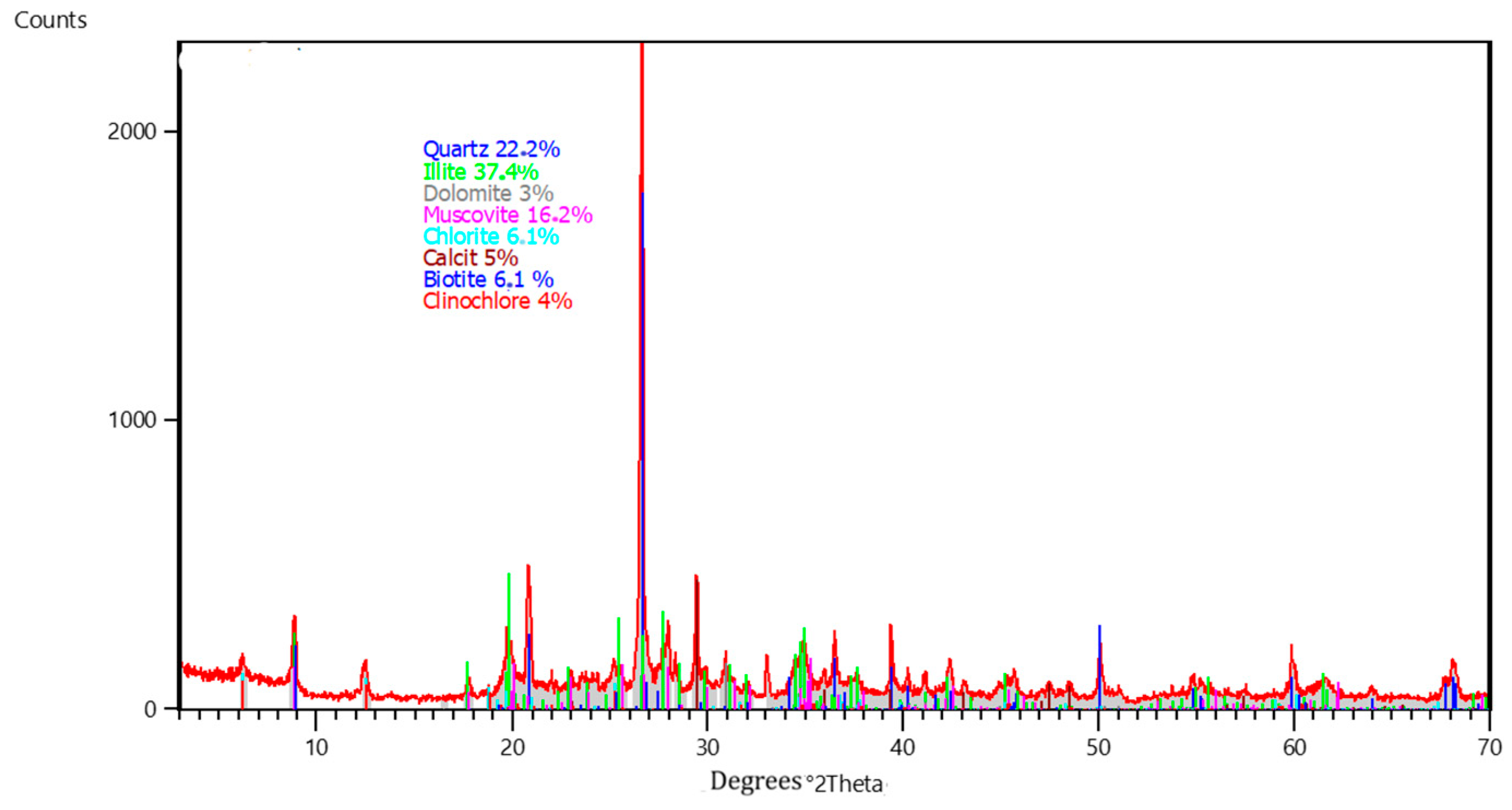

3.1. Initial Sediment Properties

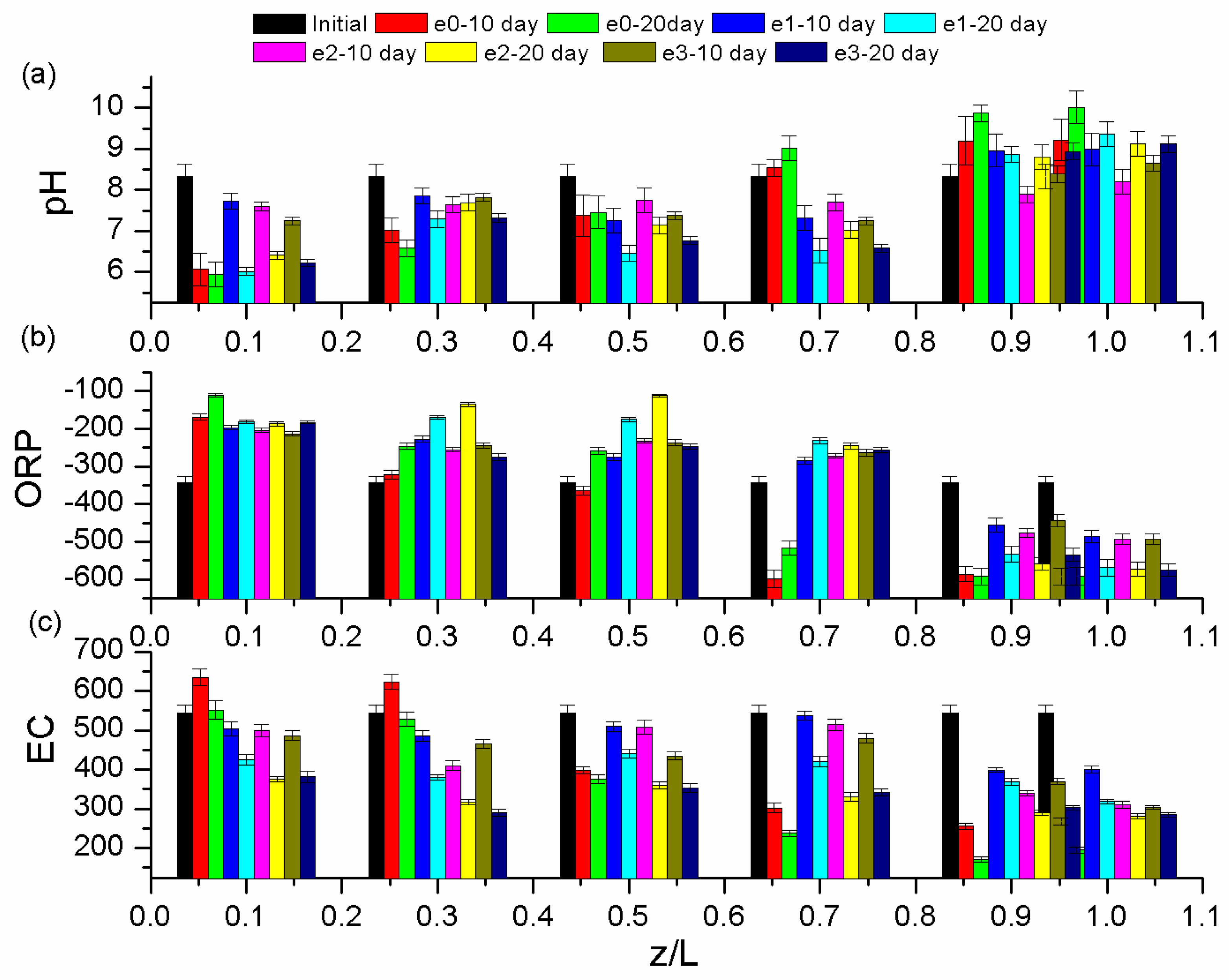

3.2. Profiles of pH, Redox Potential (ORP), and Electrical Conductivity (EC) After All EK Experiments

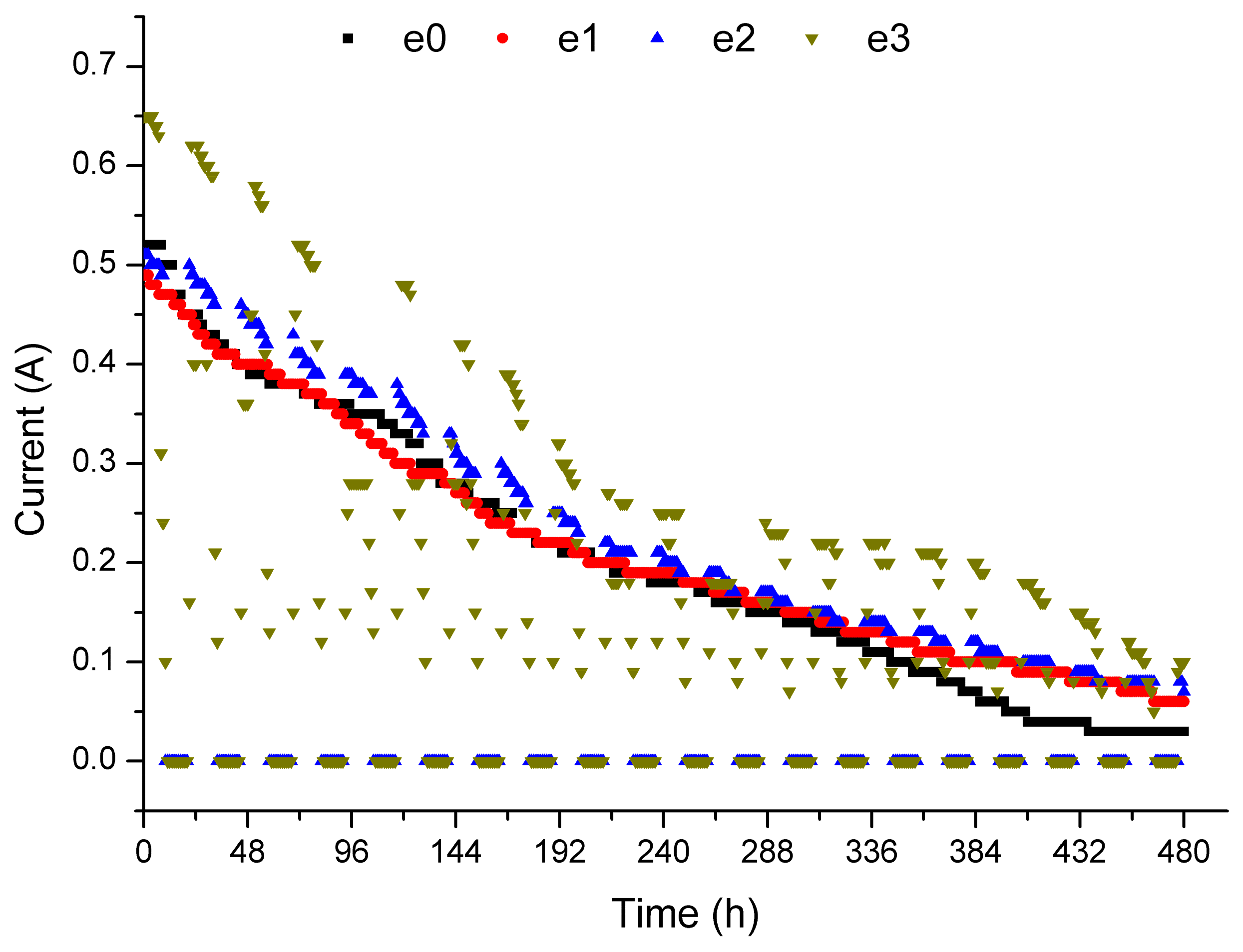

3.3. Current Changes and Energy Consumption

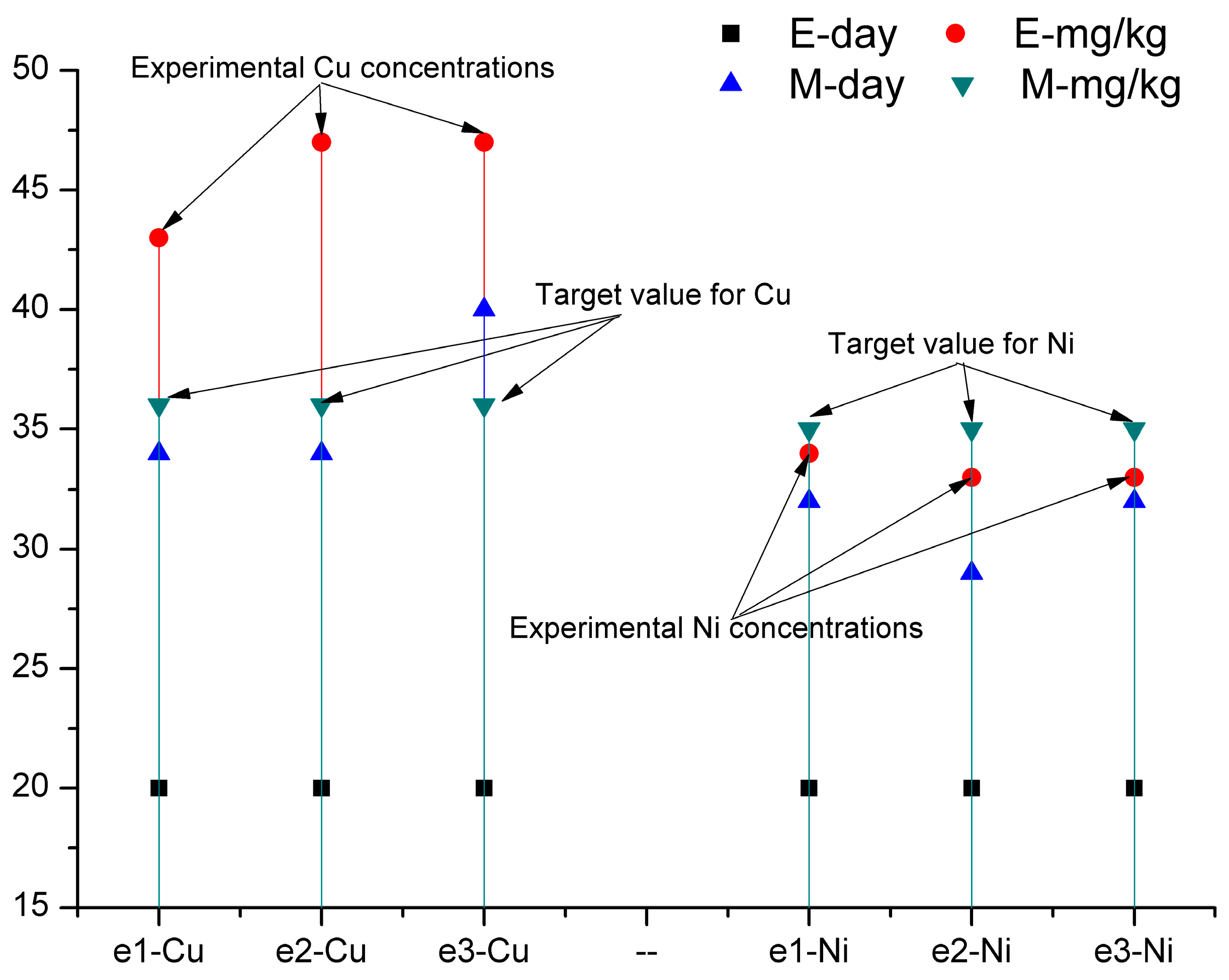

3.4. Distribution of Cu and Ni

3.5. Speciation of Cu and Ni in the EK Cell

3.6. Leached Water

3.7. Mathematical Model—Numerical Simulation of the Transport Phenomena

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EK | Electrokinetic |

| TAT | Two-anode treatment |

| VBK | Veliki Bački Canal |

| ORP | Oxidation Reduction Potential |

| BET | Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller method |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Duduković, N.; Slijepčević, N.; Tomašević Pilipović, D.; Kerkez, Đ.; Leovac Maćerak, A.; Dubovina, M.; Krčmar, D. Integrated application of green zero-valent iron and electrokinetic remediation of metal-polluted sediment. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5943–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bi, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Tao, E. Gallic acid-functionalized chitosan composite for efficient removal of hexavalent chromium in aqueous. Int. J. Bio. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Peng, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Tao, E. Chitosan-based composite featuring dual cross-linking networks for the removal of aqueous Cr (VI). Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Gu, G.; Bi, C.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Tao, E. The dual selective adsorption mechanism on low-concentration Cu (II): Structural confinement and briding effect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, G.; Yang, S.; Li, N.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Tao, E. Understanding of managese-sulfur functionalized biochar: Bridging effect enhanced specific passivation of lead in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 361, 124898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Gong, J.; Liang, J.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, M.; Liu, Y.; et al. Evaluation methods for assessing effectiveness of in-situ remediation of soil and sediment contaminated with organic pollutants and heavy metals. Environ. Int. 2017, 105, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krčmar, D.; Varga, N.; Prica, M.; Cveticanin, L.; Zukovic, M.; Dalmacija, B.; Corba, Z. Application of hexagonal two dimensional electrokinetic system on the nickel contaminated sediment and modelling the transport behavior of nickel during electrokinetic treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 192, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H. Exchange electrode-electrokinetic remediation of Cr-contaminated soil using solar energy. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 190, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wei, N.; Fan, K.; Qi, W.; Feng, J.; Lai, Z. Chemical-enhanced electrokinetic geosynthetics (EKG) electro-osmosis combined with vacuum preloading for consolidation and copper remediation in contaminated dredged sludge. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi-Zanjani, A.; Khodadadi, A. A review on enhancement techniques of electrokinetic soil remediation. Pollution 2017, 3, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Wen, D.; Xia, X.; Zhang, W.; Gu, Y. Electrokinetic remediation of chromium (Cr)-contaminated soil with citric acid (CA) and polyaspartic acid (PASP) as electrolytes. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 316, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, M.; Rong, H.; Zhang, K. Chemosphere Comparison of bioleaching and electrokinetic remediation processes for removal of heavy metals from wastewater treatment sludge. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Shao, X.; Zhang, Z. Pilot-scale electrokinetic remediation of lead polluted field sediments: Model designation, numerical simulation, and feasibility evaluation. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Qui, Z.; Tang, H.; Wang, H.; Sima, W.; Liang, C.; Liao, Y.; Wan, S.; Dong, J. Coupled with EDDS and approaching anode technique enhanced electrokinetic remediation removal heavy metal from sludge. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 272, 115975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.T.; Hofmann, A.; Reynolds, D.; Ptacek, C.J.; Cappellen, P.; Van Ottosen, L.M.; Pamukcu, S.; Alshawabekh, A.; Carroll, D.M.O.; Riis, C.; et al. Environmental Electrokinetics for a sustainable subsurface. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavat, N.; Oh, E.; Chai, G. A Review of Electrokinetic Treatment Technique for Improving the Engineering Characteristics of Low Permeable Problematic Soils. Int. J. GEOMATE 2012, 2, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Guo, S.; Li, G.; Wang, S.; Li, F.; Wu, B. The loss of mobile ions and the aggregation of soil colloid: Results of the electrokinetic effect and the cause of process termination. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 258, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; He, J.; Xin, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, T. Biosurfactants enhanced heavy metals removal from sludge in the electrokinetic treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2579–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Mohamedelhassan, E.; Yanful, E.K. Solar powered electrokinetic remediation of Cu polluted soil using a novel anode configuration. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 181, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.K.; Ryu, S.R.; Baek, K. Application of solar-cells in the electrokinetic remediation of As-contaminated soil. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 181, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.L.; Saéz, C.; Llanos, J.; Lanza, M.R.V.; Cañizares, P.; Rodrigo, M.A. Solar-powered electrokinetic remediation for the treatment of soil polluted with the herbicide 2,4-D. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 190, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, N.S.; Dalmacija, B.D.; Prica, M.D.; Kerkez, D.V.; Becelic-Tomin, M.D.; Spasojevic, J.M.; Krcmar, D.S. The application of solar cells in the electrokinetic remediation of metal contaminated sediments. Water Environ. Res. 2017, 89, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Yu, H. The influence of macroelements on energy consumption during periodic power electrokinetic remediation of heavy metals contaminated black soil. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 235, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Ceccarini, A.; Iannelli, R. Model-based optimization of field-scale electrokinetic treatment of dredged sediments. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 328, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudukovic, N.; Beljin, J.; Dubovina, M.; Tenodi, K.Z.; Cveticanin, L.; Zukovic, M.; Krcmar, D. Copper removal from sediment by electrokinetic treatment with electrodes in a hexagonal configuration. Clean Soil Air Water 2023, 51, 22000402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprocati, R.; Masi, M.; Muniruzzaman, M.; Rolle, M. Modeling electrokinetic transport and biogeochemical reactions in porous media: A multidimensional Nernst–Planck–Poisson approach with PHREEQC coupling. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 127, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wu, X.; Li, R.; Tang, X.; Xiao, S.; Scholz, M. Critical Review of Electro-kinetic Remediation of Contaminated Soils and Sediments: Mechanisms, Performances and Technologies. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRPS ISO 5667-12:2019; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 12: Guidance on Sampling of Bottom Sediments from Rivers, Lakes and Estuarine Areas. Serbian Institute for Standardization (ISS): Belgrade, Serbia, 28 February 2019.

- SRPS ISO 11464:2004; Soil Quality—Pretreatment of Samples for Physico-Chemical Analyses. Institute of Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2004.

- ISO 11277:2009; Soil Quality—Determination of Particle Size Distribution in Mineral Soil Material—Method by Sieving and Sedimentation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- SRPS EN 12880:2007; Characterization of Sludges—Determination of Dry Residue and Water Content. Institute of Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007.

- SRPS EN 12879:2007; Characterization of Sludges—Determination of the Loss on Ignition of Dry Mass. Institute of Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007.

- SRPS ISO 10390:2007; Soil Quality—Determination of pH. Institute of Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007.

- USEPA METHOD 9080; Cation-Exchange Capacity of Soils (Ammonium Acetate). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Test Method 3051A; Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, Soils, and Oils. USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Sabra, N.; Dubourguier, H.; Hamieh, T. Sequential Extraction and Particle Size Analysis of Heavy Metals in Sediments Dredged from the Deûle Canal, France. Open Environ. Engineer. J. 2011, 4, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA Method 7000B; Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- USEPA Method 7010 (SW-846); Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Nham, H.T.T.; Greskowiak, J.; Nodler, K.; Rahman, M.A.; Spachos, T.; Ruseberg, B.; Massmann, G.; Sauter, M.; Licha, T. Modeling the transport behavior of 16 emerging organic contaminants during soil aquifer treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 514, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, P.P. A Modular Tree-Dimensional Multispecies Transport Model for Simulation of Advection, Dispersion, and Chemical Reactions of Contaminants in Groundwater Systems, DTIC Document, 1999, p. 169. Available online: http://hydro.geo.ua.edu/mt3d/mt3dmanual.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Chakraborty, R.; Ghosh, A.; Ghosh, S.; Mukherjee, S. Evolution of contaminant transport parameters for hexavalent chromium migration through saturated soil media. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 5687–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Garcia, J.M.; Baek, K.; Alshawabkeh, J.D.; Alshawabkeh, A.N. A generalized model for transport of contaminants in soil by electric fields. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2012, 47, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajić, L.; Dalmacija, B.; Perović, S.U.; Krčmar, D.; Rončević, S.; Tomašević, D. Electrokinetic Treatment of Cr-, Cu-, and Zn-Contaminated Sediment: Cathode Modification. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2013, 30, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y. Measurement of Cu and Zn adsorption onto surficial sediment components: New evidence for less importance of clay minerals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 189, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Gazette of RS, No 50/12, Regulation on limit values for pollutants in surface and groundwaters and sediments, and the deadlines for their achievement, Belgrade, Serbia, 2012. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/uredba-granicnim-vrednostima-zagadjujucih-materija-vodama.html (accessed on 5 January 2026). (In Serbian)

- Yang, J.; Cao, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, C.; Cai, W.; Fang, H.; Peng, X. Speciation of metals and assessment of contamination in surface sediments from Daya Bay, South China Sea. Sustainability 2014, 6, 9096–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.K. Metal fractionation study on bed sediments of River Yamuna, India. Water Res. 2004, 38, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djukic, A.B. Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions onto Montmorillonite/Kaolinite Clay-Titanium(iv)oxide composite. Doctoral Dissertation, University Of Belgrade, Faculty of Physical Chemistry, Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, P.C.; Hillier, S.; Wall, A.J. Stepwise effects of the BCR sequential chemical extraction procedure on dissolution and metal release from common ferromagnesian clay minerals: A combined solution chemistry and X-ray powder diffraction study. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 407, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihović, S. Optičke Karakteristike Minerala u Propuštenoj Svjetlosti; Ars Grafika: Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2007. (In Bosnian) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.H.; Liu, J.S.; Lin, C.W. Heavy metal removal and recovery from contaminated sediments based on bioelectrochemical systems: Insights, progress, and perspectives. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2025, 196, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasciucco, E.; Pasciucco, F.; Castagnoli, A.; Iannelli, R.; Pecorini, I. Removal of heavy metals from dredging marine sediments via electrokinetic hexagonal system: A pilot study in Italy. Heliyon 2024, 10, 27616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, Z.; Zeng, G.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Z.; Cui, F.; Zhu, M.; Shen, L.; Hu, L. Effects of sediment geochemical properties on heavy metal bioavailability. Environ. Int. 2014, 73, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-F.; Song, Y.-H.; Yuan, P.; Cui, X.-Y.; Qiu, G.-L. The remediation of heavy metals contaminated sediment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Latsos, A.; Gidarakos, E. Performance of electroremediation in real contaminated sediments using a big cell, periodic voltage and innovative surfactants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 320, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Lekkas, N.; Smponias, A.; Gidarakos, E. Sequential application of chelating agents and innovative surfactants for the enhanced electroremediation of real sediments from toxic metals and PAHs. Chemosphere 2014, 105, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajic, L.; Dalmacija, B.; Ugarcina-Perovic, S.; Watson, M.; Dalmacija, M. Influence of nickel speciation on electrokinetic sediment remediation efficiency. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2011, 17, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M.H.; Mu’Azu, N.D.; Lukman, S.; Bukhari, A. Integrated electrokinetics-adsorption remediation of saline-sodic soils: Effects of voltage gradient and contaminant concentration on soil electrical conductivity. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 618495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Chakrabarti, M.H.; Irfan, M.F.; Hajimolana, S.A.; Hussain, M.A.; Diya’uddeen, B.H.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Electrokinetic remediation of nickel from low permeability soil. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 4264–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yao, C. Electrokinetic Recovery of Copper, Nickel, and Zinc from Wastewater Sludge: Effects of Electrical Potentials. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2012, 29, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Mohamedelhassan, E. Electrokinetic Remediation with Solar Power for a Homogeneous Soft Clay Contaminated with Copper. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. Remediat. 2012, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeon, E.K.; Jung, J.M.; Ryu, S.R.; Baek, K. In-situ field application of electrokinetic remediation for an As-, Cu-, and Pb-contaminated rice paddy site using parallel electrode configuration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15763–15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammami, M.T.; Benamar, A.; Koltalo, F.; Wang, H.Q.; LeDerf, F. Heavy metals removal from dredged sediments using electro kinetics. E3S Web Conf. 2013, 1, 01004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcino, N.; Crisafi, F.; Catalfamo, M.; Denaro, R.; Smedile, F. Electrokinetic Remediation in Marine Sediment: A Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landner, L.; Reuther, R. Speciation, mobility and bioavailability of metals in the environment. Met. Soc. Environ. 2005, 8, 139–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Maah, M.J.; Yusoff, I. Study of chemical forms of heavy metals collected from the sediments of tin mining catchment. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2022, 24, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowska, M. Migration and forms of metals in bottom sediments of Czerniakowskie Lake. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013, 90, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Kim, D.H.; Yoo, J.C.; Baek, K. Electrokinetic extraction of heavy metals from dredged marine sediment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 79, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedex, N.; Abdelouahabderraq, R. Speciation of four heavy metals in agricultural soils around DraaLasfarmine area in Marrakech (Morocco). Pollution 2015, 1, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Luo, Q.S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.B.; Li, B.Z. Effects of electrokinetic treatment of contaminated sludge on migration and transformation of Cd, Ni and Zn in various bonding states. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jin, C.; Zhao, Z.; Tian, G. 2D crossed electric field for electrokinetic remediation of chromium contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Water content (%) | 61.2 ± 2.8 | ||

| Organic matter (%) | 16.8 ± 0.5 | ||

| Clay (%) | 48.1 ± 1.8 | ||

| CEC, meq/100 g | 20.6 ± 0.9 | ||

| BET (m2g−1) | 13.0 ± 0.4 | ||

| Metal (mg/kg) | Corrected value (mg/kg) | Class | |

| Cd | 2.55 ± 0.09 | 1.84 | 1 |

| Cr | 111 ± 5.32 | 76.0 | 0 |

| Cu | 146 ± 5.87 | 97.4 | 3 |

| Pb | 97.3 ± 4.23 | 72.0 | 0 |

| Ni | 93.5 ± 3.71 | 56.3 | 3 |

| Zn | 288 ± 9.65 | 183.7 | 1 |

| Sediment fractions | Cu (mg/kg) | Cu (%) | |

| Weak acid soluble | 28.6 ± 0.94 | 2.22 | |

| Reducible | 59.3 ± 2.61 | 56.1 | |

| Oxidizable | 34.4 ± 1.47 | 20.5 | |

| Residual | 34.8 ± 1.52 | 21.2 | |

| Sediment fractions | Ni (mg/kg) | Ni (%) | |

| Weak acid soluble | 21.2 ± 0.88 | 24.7 | |

| Reducible | 27.1 ± 1.12 | 37.8 | |

| Oxidizable | 14.8 ± 0.63 | 10.5 | |

| Residual | 22.2 ± 0.96 | 27.0 | |

| Treatment | Metal | Cu (mg/kg)-10 day | Cu (mg/kg)-20 day | Ni (mg/kg)-10 day | Ni (mg/kg)-20 day | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z/L | MV | CV | Class | MV | CV | Class | MV | CV | Class | MV | CV | Class | |

| e0 | 0.1 | 96.5 ±4.2 | 64.1 | 2 | 68.1 ±2.9 | 45.5 | 2 | 70.5 ± 3.2 | 42.5 | 2 | 59.1 ± 2.6 | 35.6 | 2 |

| 0.3 | 102 ± 4.4 | 68.1 | 2 | 84.9 ±3.5 | 56.7 | 2 | 66.9 ± 2.9 | 40.3 | 2 | 66.2 ± 2.8 | 39.9 | 2 | |

| 0.5 | 120 ± 5.1 | 80.1 | 2 | 100 ± 4.7 | 66.7 | 2 | 76.5 ± 3.3 | 46.1 | 3 | 61.6 ± 1.9 | 37.1 | 2 | |

| 0.7 | 151 ± 5.9 | 100.8 | 3 | 176 ± 7.9 | 117 | 3 | 86.2 ± 3.9 | 51.9 | 3 | 104 ± 4.8 | 62.7 | 3 | |

| 0.9 | 164 ± 6.3 | 109.5 | 3 | 228 ± 9.3 | 152 | 3 | 106 ± 4.8 | 63.9 | 3 | 122 ± 5.7 | 73.5 | 3 | |

| 1 | 158 ± 5.3 | 105.5 | 3 | 207 ± 8.8 | 138 | 3 | 100 ± 4.2 | 60.2 | 3 | 124 ± 5.9 | 74.7 | 3 | |

| e1 | 0.1 | 78.3 ±3.1 | 52.3 | 2 | 52.4 ±2.2 | 35 | 1 | 64.4 ± 2.6 | 38.8 | 2 | 51.8 ± 2.2 | 31.2 | 0 |

| 0.3 | 79.4 ±2.9 | 53.0 | 2 | 47.4 ± 1.9 | 31.6 | 1 | 64.9 ± 2.5 | 39.1 | 2 | 50.4 ± 2.1 | 30.4 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 77.8 ±2.8 | 51.9 | 2 | 54.1 ± 2.3 | 36.1 | 2 | 65.4 ± 2.7 | 39.4 | 2 | 54.1 ± 2.4 | 32.6 | 0 | |

| 0.7 | 81.4 ±3.2 | 54.3 | 2 | 56.4 ±2.6 | 37.6 | 2 | 70.0 ± 3.1 | 42.2 | 2 | 53.3 ± 2.4 | 32.1 | 0 | |

| 0.9 | 133 ± 6.4 | 89.0 | 2 | 111 ± 5.1 | 74.4 | 2 | 82.7 ± 3.6 | 49.8 | 3 | 72.6 ± 3.3 | 43.7 | 2 | |

| 1 | 153 ± 6.9 | 102.1 | 3 | 165 ± 7.8 | 110 | 3 | 96.7 ± 4.5 | 58.3 | 3 | 105 ± 4.7 | 63.1 | 3 | |

| e2 | 0.1 | 86 ± 3.9 | 57.4 | 2 | 55.9 ± 2.2 | 37.4 | 2 | 62.6 ± 2.1 | 37.7 | 2 | 49.3 ± 2.1 | 29.7 | 0 |

| 0.3 | 85.1 ±3.5 | 56.8 | 2 | 59.7 ± 2.4 | 39.8 | 2 | 60.9 ± 2.3 | 36.7 | 2 | 53.2 ± 2.3 | 32.0 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 89.7 ±3.7 | 59.9 | 2 | 59.7 ± 2.8 | 39.9 | 2 | 65.2 ± 2.7 | 39.2 | 2 | 48.5 ± 2.0 | 29.2 | 0 | |

| 0.7 | 93.7 ±4.2 | 62.5 | 2 | 64.8 ± 2.9 | 43.2 | 2 | 67.3 ± 2.9 | 40.5 | 2 | 49.1 ± 2.2 | 29.5 | 0 | |

| 0.9 | 135 ± 6.5 | 90.2 | 3 | 110 ± 5.1 | 73.2 | 2 | 81.7 ± 3.5 | 49.2 | 3 | 72.4 ± 3.3 | 43.6 | 2 | |

| 1 | 153 ± 7.1 | 102.2 | 3 | 178 ± 8.4 | 119 | 3 | 97.0 ± 4.6 | 58.4 | 3 | 103 ± 4.8 | 61.9 | 3 | |

| e3 | 0.1 | 90.7 ±3.5 | 60.5 | 2 | 61.3 ± 2.8 | 40.9 | 2 | 56.5 ± 1.9 | 34.0 | 2 | 46.0 ± 1.8 | 27.7 | 0 |

| 0.3 | 94.5 ±4.1 | 63.1 | 2 | 56.1 ± 2.3 | 37.4 | 2 | 62.4 ± 2.9 | 37.6 | 2 | 52.6 ± 2.2 | 31.7 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 90.3 ±3.6 | 60.3 | 2 | 61.4 ± 2.6 | 41.0 | 2 | 62.5 ± 2.9 | 37.7 | 2 | 49.3 ± 2.1 | 29.7 | 0 | |

| 0.7 | 97.5 ±4.4 | 65.1 | 2 | 56.7 ± 2.1 | 37.8 | 2 | 67.3 ± 3.1 | 40.5 | 2 | 50.1 ± 2.2 | 30.2 | 0 | |

| 0.9 | 136 ± 5.8 | 91 | 3 | 118 ± 4.2 | 78.6 | 2 | 83.9 ± 3.7 | 50.5 | 3 | 74.0 ± 3.5 | 44.6 | 2 | |

| 1 | 162 ± 7.7 | 107.9 | 3 | 169 ± 7.7 | 113 | 3 | 102 ± 4.9 | 61.3 | 3 | 106 ± 4.4 | 64 | 3 | |

| Experiment Assignation | Removal Efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cu | Ni | |

| Fe0 | 10 | 11 |

| e1 | 56 | 39 |

| e2 | 52 | 41 |

| e3 | 52 | 41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duduković, N.; Krčmar, D.; Tomašević Pilipović, D.; Slijepčević, N.; Žmukić, D.; Kerkez, Đ.; Leovac Maćerak, A. Ex Situ Sediment Remediation Using the Electrokinetic (EK) Two-Anode Technique (TAT) Supported by Mathematical Modeling. Technologies 2026, 14, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020086

Duduković N, Krčmar D, Tomašević Pilipović D, Slijepčević N, Žmukić D, Kerkez Đ, Leovac Maćerak A. Ex Situ Sediment Remediation Using the Electrokinetic (EK) Two-Anode Technique (TAT) Supported by Mathematical Modeling. Technologies. 2026; 14(2):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020086

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuduković, Nataša, Dejan Krčmar, Dragana Tomašević Pilipović, Nataša Slijepčević, Dragana Žmukić, Đurđa Kerkez, and Anita Leovac Maćerak. 2026. "Ex Situ Sediment Remediation Using the Electrokinetic (EK) Two-Anode Technique (TAT) Supported by Mathematical Modeling" Technologies 14, no. 2: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020086

APA StyleDuduković, N., Krčmar, D., Tomašević Pilipović, D., Slijepčević, N., Žmukić, D., Kerkez, Đ., & Leovac Maćerak, A. (2026). Ex Situ Sediment Remediation Using the Electrokinetic (EK) Two-Anode Technique (TAT) Supported by Mathematical Modeling. Technologies, 14(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020086