Enhancing the Performance of Materials in Ballistic Protection Using Coatings—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials for Ballistic Protection

2.1. Metals

2.2. Ceramics

2.3. Polymeric Materials

- Para-aramid (e.g., Kevlar, Twaron, Technora);

- Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) [42].

2.4. Composite Materials

3. Coatings for Ballistic Enhancement

3.1. Coating Methods Used in Ballistic Protection

3.1.1. Sol–Gel Deposition Method

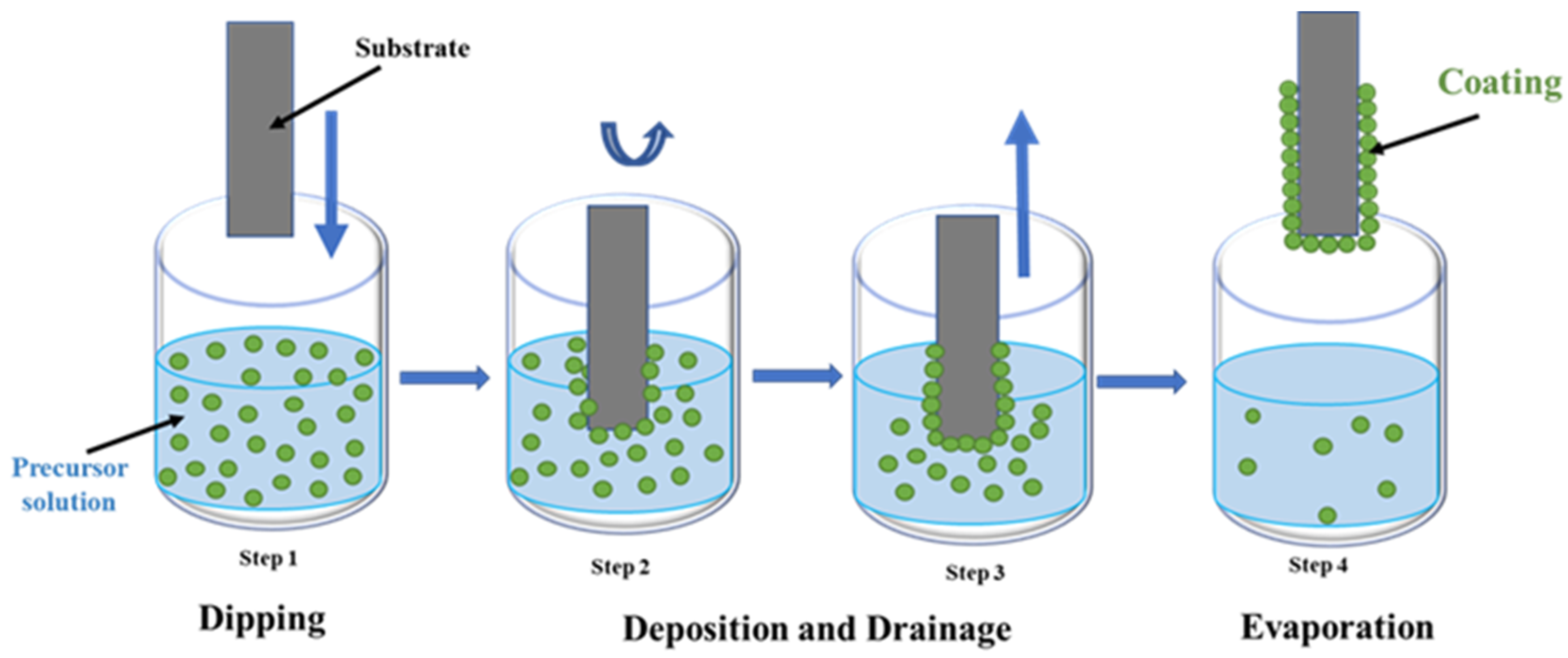

3.1.2. Dip-Coating Deposition Method

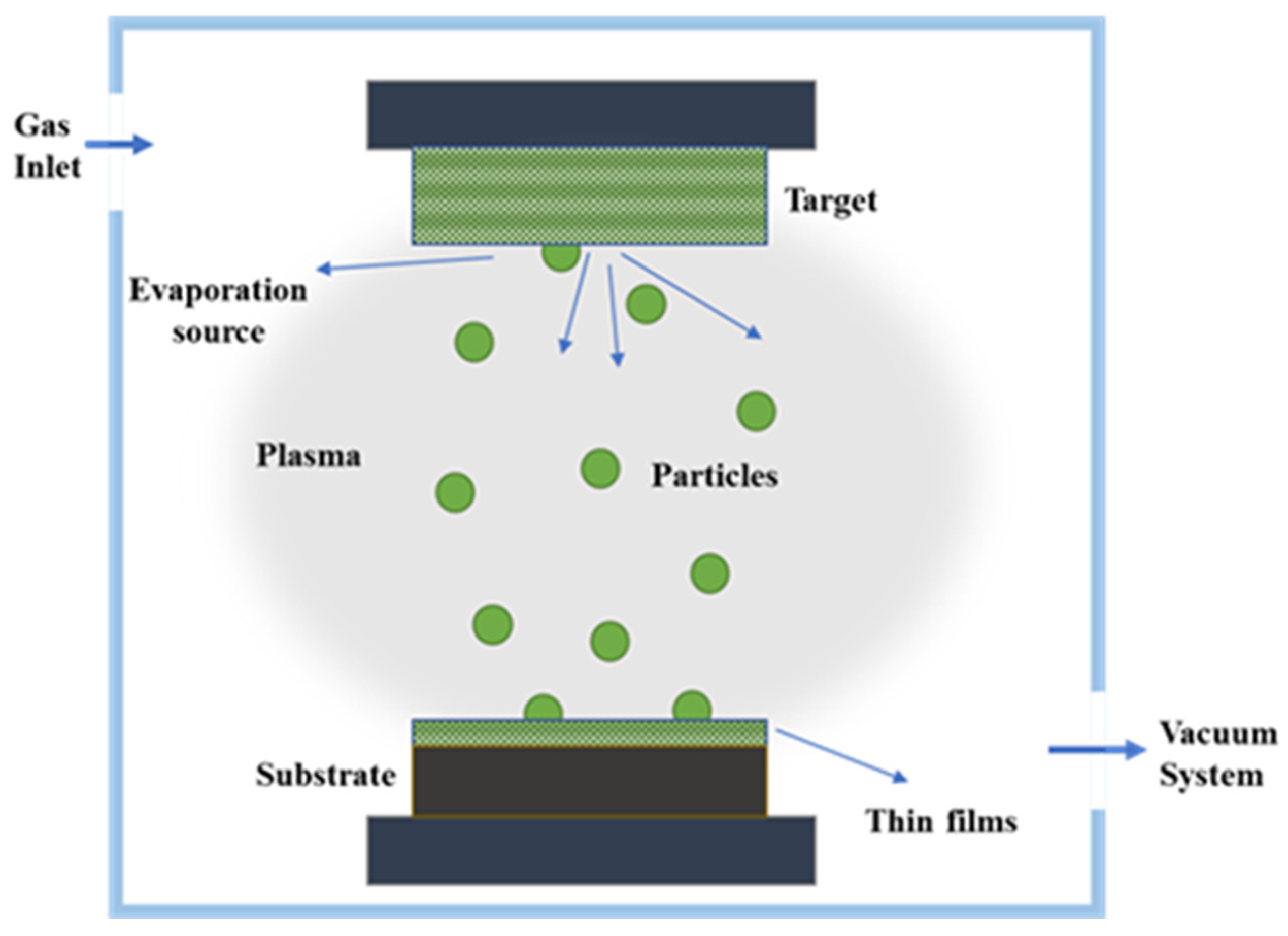

3.1.3. Physical Vapor Deposition Process

3.1.4. Chemical Vapor Deposition Process

3.1.5. Spray Coatings

3.2. Coatings for Enhanced Ballistic Performance

3.2.1. Nanosilica Coatings

3.2.2. Coatings Based on Graphene

3.2.3. Coatings with Carbon Nanotubes

3.2.4. Zinc Oxide Nanowire (ZnO NWs) Coatings

3.3. Economic and Scalability Considerations for Coating Materials and Processes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X. (Ed.) Advanced Fibrous Composite Materials for Ballistic Protection; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelko, O.; Horban, A. Analysis of the History of Creation and Improvement of Personal Protective Equipment: From Bronze Armor to Modern Bulletproof Vests. Hist. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R.-C.; Yin, L.-K.; Wang, J.-R.; Chen, Z.-G.; Hu, D.-Q. Study on the Performance of Ceramic Composite Projectile Penetrating into Ceramic Composite Target. Def. Technol. 2017, 13, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitotaw, D.B.; Ahrendt, D.; Kyosev, Y.; Kabish, A.K. A Review on the Performance and Comfort of Stab Protection Armor. Autex Res. J. 2021, 21, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, N.V.; Gao, X.-L.; Zheng, J.Q. Ballistic Resistant Body Armor: Contemporary and Prospective Materials and Related Protection Mechanisms Available to Purchase. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2009, 62, 050802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, E.E.; Szpunar, J.A.; Odeshi, A.G. Ballistic Impact Response of Laminated Hybrid Materials Made of 5086-H32 Aluminum Alloy, Epoxy and Kevlar Fabrics Impregnated with Shear Thickening Fluid. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 87, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, M.A.; Boussu, F.; Bruniaux, P.; Loghin, C.; Cristian, I. Ballistic Impact Mechanisms—A Review on Textiles and Fibre-Reinforced Composites Impact Responses. Compos. Struct. 2019, 223, 110966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavaş, M.O.; Avcı, A.; Şimşir, M.; Akdemir, A. Ballistic Performance of Kevlar49/UHMW-PEHB26 Hybrid Layered Composite. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2015, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, D.C.; Shockey, D.A.; Simons, J.W. Slow Penetration of Ballistic Fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2003, 73, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, B.; Chen, X. Impact Performance of Single-Piece Continuously Textile Reinforced Riot Helmet Shells. J. Compos. Mater. 2014, 48, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, M.R.; Sultana, M.T.H.; Hamdan, A.; Nor, A.F.M.; Jayakrishna, K. Flexural and Impact Properties of a New Bulletproof Vest Insert Plate Design Using Kenaf Fibre Embedded with X-Ray Films. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 11193–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X. Investigation of Energy Absorption Mechanisms in a Soft Armor Panel under Ballistic Impact. Text. Res. J. 2017, 87, 2475–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdi, T.I. Modeling and Simulation of Progressive Penetration of Multilayered Ballistic Fabric Shielding. Comput. Mech. 2002, 29, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, K.; Kang, T.J. Numerical Analysis of Energy Absorption Mechanism in Multi-Ply Fabric Impacts. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, M.; Kuş, A.; Eren, R. An Investigation into Ballistic Performance and Energy Absorption Capabilities of Woven Aramid Fabrics. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2008, 35, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Long, Y.; Ji, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Zhou, Y. Influence of Layer Number and Air Gap on the Ballistic Performance of Multi-Layered Targets Subjected to High Velocity Impact by Copper EFP. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2018, 112, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, S. Ballistic Composites, the Present and the Future. In Smart and Advanced Ceramic Materials and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIJ 0101.06/0101.07; Ballistic Resistance of Body Armor. U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- NATO AEP-55/STANAG 4569; Protection Levels for Occupants of Logistic and Light Armoured Vehicles. NATO Standardization Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Balos, S.; Howard, D.; Brezulianu, A.; Labus Zlatanović, D. Perforated Plate for Ballistic Protection—A Review. Metals 2021, 11, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, B.; Cabrilo, A. Effect of Heat Input on the Ballistic Performance of Armor Steel Weldments. Materials 2021, 14, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Tufail, M.; Chandio, A.D. Characterization of Microstructure, Phase Composition, and Mechanical Behavior of Ballistic Steels. Materials 2022, 15, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovski, J.; Kunc, R.; Pepel, V.; Prebil, I. Flow and Fracture Behavior of High-Strength Armor Steel PROTAC 500. Mater. Des. 2015, 66, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, C.; Tiganescu, T.V.; Antoniac, A.; Iorga, O.; Ghiban, B.; Pascu, A.; Streza, A.; Antoniac, I. Mechanical Properties and Ballistic Performance for Different Coatings on HARDOX 450 Steel for Defense Applications. Crystals 2025, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viliš, J.; Kosiuczenko, K.; Nowakowski, M.; Tupaj, M.; Trytek, A.; Zouhar, J.; Vítek, R.; Gregor, L.; Pokorný, Z. Comprehensive Evaluation of Layered Composite Protection Performance for Light Armored Vehicles. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, D.; Canpolat, B.H.; Cora, Ö.N. Ballistic Performances of Ramor 500, Armox Advance and Hardox 450 Steels under Monolithic, Double-Layered, and Perforated Conditions. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 51, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby-Thomas, G.J.; Wood, D.C.; Hameed, A.; Painter, J.; Fitzmaurice, B. On the Effects of Powder Morphology on the Post-Comminution Ballistic Strength of Ceramics. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 100, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittari, J.; Subhash, G.; Zheng, J.; Halls, V.; Jannotti, P. The Rate-Dependent Fracture Toughness of Silicon Carbide- and Boron Carbide-Based Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 4411–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, L.M.; Manes, A.; Giglio, M. An Analytical Model for Ballistic Impacts against Ceramic Tiles. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 21249–21261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldin, M.S.; Berendeev, N.N.; Melekhin, N.V.; Popov, A.A.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Chuvildeev, V.N. Review of Ballistic Performance of Alumina: Comparison of Alumina with Silicon Carbide and Boron Carbide. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 25201–25213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, J.I.N.; Da Silveira, P.H.P.M.; Monteiro, S.N.; Pereira, A.S.; Lima, E.S. Mechanical, Microstructural Properties and Ballistic Performance of SiC/Si Ceramics against 5.56 × 45 mm Projectile. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Schaefer, M.C.; Haber, R.A.; Hemker, K.J. Experimental Observations of Amorphization in Stoichiometric and Boron-Rich Boron Carbide. Acta Mater. 2019, 181, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, H.; Yang, Q.; Rivera, J.; Crystal, I.R.; Sun, L.Y.; Thorpe, F.; Rosenberg, W.; McCormack, S.J.; King, G.C.S.; Cahill, J.T.; et al. Thermostructural Evolution of Boron Carbide Characterized Using In-Situ X-Ray Diffraction. Acta Mater. 2024, 265, 119597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.; Rabet, L.; Imad, A.; Coghe, F.; Van Roey, J.; Guéders, C.; Gallant, J. Ballistic Impact Response of an Alumina-Based Granular Material: Experimental and Numerical Analyses. Powder Technol. 2021, 385, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z. Experimental and Theoretical Study of Cone Angle in Alumina Tiles under Ballistic Impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 192, 105025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jia, N.; Zhou, J.Q.; Jiao, Y.; Lei, H. Designing SiC Ceramic Composite Armor Structure to Resist Multiple Impacts from Armor-Piercing Incendiary Bullets. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2025, 203, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIJ 0123.00; Specification for NIJ Ballistic Protection Levels and Associated Test Threats. National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Xu, D.; Huang, Z.; Chen, G.; Ren, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Experimental Investigation on the Ballistic Performance of B4C/Aramid/UHMWPE Composite Armors against API Projectile under Different Temperatures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 196, 111553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, H.; Liang, K.; Huang, Y. Impact Simulation and Ballistic Analysis of B4C Composite Armour Based on Target Plate Tests. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 10035–10049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Hazell, P.J.; Han, Z.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; et al. Ballistic Performance of Functionally Graded B4C/Al Composites without Abrupt Interfaces: Experiments and Simulations. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, K.; Nawab, Y. Fibers for Protective Textiles. In Fibers for Technical Textiles; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, D.K.Y.; Ruan, S.; Gao, P.; Yu, T. High-Performance Ballistic Protection Using Polymer Nanocomposites. In Advances in Military Textiles and Personal Equipment; Sparks, E., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwolek, S.L. Chemical Heritage Foundation, 2015. Available online: http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/online-resources/chemistry-in-history/themes/petrochemistry-and-synthetic-polymers/synthetic-polymers/kwolek.aspx (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Protyai, M.I.H.; Adib, F.M.; Taher, T.I.; Karim, M.R.; Rashid, A.B. Performance Evaluation of Kevlar Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composite by Depositing Graphene/SiC/Al2O3 Nanoparticles. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 6, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont. Kevlar® Aramid Fiber. DuPont Romania, 2015. Available online: http://www.dupont.com/products-and-services/fabrics-fibers-nonwovens/fibers/brands/kevlar.html (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- He, Q.; Cao, S.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, S.; Wang, P.; Gong, X. Impact Resistance of Shear Thickening Fluid/Kevlar Composite Treated with Shear-Stiffening Gel. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 106, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, A.; Liaghat, G.; Vahid, S.; Sabet, A.R.; Hadavinia, H. Ballistic Performance of Kevlar Fabric Impregnated with Nanosilica/PEG Shear Thickening Fluid. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 162, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.L.; Yoon, B.I.; Paik, J.G.; Kang, T.J. Ballistic Performance of P-Aramid Fabrics Impregnated with Shear Thickening Fluid; Part I—Effect of Laminating Sequence. Text. Res. J. 2012, 82, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.K.; Feng, X.Y. The Ballistic Performance of Multi-Layer Kevlar Fabrics Impregnated with Shear Thickening Fluids. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 782, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Jamal, N.B.; Shaw, A.; Deb, A. Numerical Investigation of Ballistic Performance of Shear Thickening Fluid (STF)-Kevlar Composite. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 164, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Jaeger, H.M. Shear Thickening in Concentrated Suspensions: Phenomenology, Mechanisms and Relations to Jamming. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2014, 77, 046602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egres, R.G.; Wagner, N.J. The Rheology and Microstructure of Acicular Precipitated Calcium Carbonate Colloidal Suspensions through the Shear Thickening Transition. J. Rheol. 2005, 49, 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.B.; Wen, H.M. A Constitutive Model for Shear Thickening Fluid (STF) Impregnated Kevlar Fabric Subjected to Impact Loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 191, 104990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, M.; Xuan, S.; Jiang, W.; Cao, S.; Gong, X. Shear Dependent Electrical Property of Conductive Shear Thickening Fluid. Mater. Des. 2017, 121, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, A.; Paiva, F.; Odenbach, S.; Calado, V. Influence of Particle Shape and Sample Preparation on Shear Thickening Behavior of Precipitated Calcium Carbonate Suspensions. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.B.; Xuan, S.H.; Jiang, W.Q.; Gong, X.L. High Performance Shear Thickening Fluid Based on Calcinated Colloidal Silica Microspheres. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 085033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürgen, S.; Kuşhan, M.C. The Stab Resistance of Fabrics Impregnated with Shear Thickening Fluids Including Various Particle Size of Additives. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 94, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, R.; Jiang, W.; Chen, W. Research on the Adaptability of STF-Kevlar to Ambient Temperature under Low-Velocity Impact Conditions. Polym. Test. 2024, 133, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Luo, G. Design of the Ballistic Performance of Shear Thickening Fluid (STF) Impregnated Kevlar Fabric via Numerical Simulation. Mater. Des. 2023, 226, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hong, X.; Lei, Z.; Bai, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J. Shear Response Behavior of STF/Kevlar Composite Fabric in Picture Frame Test. Polym. Test. 2022, 113, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Hou, J.; Wang, R.; Han, Y.; Chen, C.; Chang, M.; Guo, K.; He, L. Energy Absorption Characteristics of STF Impregnated Kevlar Fabric Coating GFRP Composite Structure by Projectile High-Velocity Impact. Polym. Test. 2024, 140, 108596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Li, M.; Li, R.; He, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. The Effect of STF-Kevlar Composite Materials on the Impact Response of Fibre Metal Laminates. Compos. Commun. 2024, 48, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexe, F.; Sau, C.; Iorga, O.; Toader, G.; Diacon, A.; Rusen, E.; Lazaroaie, C.; Ginghina, R.E.; Tiganescu, T.V.; Teodorescu, M.; et al. Experimental Investigations on Shear Thickening Fluids as “Liquid Body Armors”: Non-Conventional Formulations for Ballistic Protection. Polymers 2024, 16, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.P.; Karthikeyan, K.; Deshpande, V.S.; Fleck, N.A. The High Strain Rate Response of Ultra High Molecular-Weight Polyethylene: From Fibre to Laminate. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2013, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malito, L.G.; Arevalo, S.; Kozak, A.; Spiegelberg, S.; Bellare, A.; Pruitt, L. Material Properties of Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene: Comparison of Tension, Compression, Nanomechanics and Microstructure across Clinical Formulations. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 83, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.M. (Ed.) UHMWPE Biomaterials Handbook: Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene in Total Joint Replacement and Medical Devices; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elkarem, A.H. A Study on Dyneema Fabric for Soft Body Armor. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Dai, K.; Lv, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Material and Structure of Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Body Armor on Ballistic Limit Velocity: Numerical Simulation. Polymers 2024, 16, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, M. Comparison of Ballistic Performance and Energy Absorption Capabilities of Woven and Unidirectional Aramid Fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, N.M.; Sastranegara, A.; Hernawan, R.; Anggraini, L. Impact Behavior of Multi-Layered UHMWPE Vests Reinforced with Titanium and PVC for Ballistic Protection. Indones. J. Comput. Eng. Des. (IJoCED) 2025, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, X.; Liu, J.; Fu, H.; Li, S.; He, C. Design and Ballistic Penetration of “SiC/Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE” Composite Armor. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 563, 042009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundhir, N.; Pathak, H.; Zafar, S. Ballistic Impact Performance of Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) Composite Armour. Sådhanå 2021, 46, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, V.; Subramani, S.P.; Palaniappan, S.K.; Mylsamy, B.; Aruchamy, K. Characterization on Thermal Properties of Glass Fiber and Kevlar Fiber with Modified Epoxy Hybrid Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 3158–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradar, A.; Arulvel, S.; Kandasamy, J.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Shahar, F.S.; Najeeb, M.I.; Gaff, M.; Hui, D. Nanocoatings for Ballistic Applications: A Review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J.; Gu, J.; Wujcik, E.K.; Shao, L.; Wang, N.; Wei, H.; Scaffaro, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. Introducing Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkunte, S.; Fidan, I.; Naikwadi, V.; Gudavasov, S.; Ali, M.A.; Mahmudov, M.; Hasanov, S.; Cheepu, M. Advancements and Challenges in Additively Manufactured Functionally Graded Materials: A Comprehensive Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doddamani, S.; Kulkarni, S.M.; Joladarashi, S.; TS, M.K.; Gurjar, A.K. Analysis of Light Weight Natural Fiber Composites against Ballistic Impact: A Review. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, K.J.; Burela, R.G. A Review of Recent Research on Multifunctional Composite Materials and Structures with Their Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 5580–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Vilatela, J.J.; Molina-Aldareguía, J.M.; Lopes, C.S.; LLorca, J. Structural Composites for Multifunctional Applications: Current Challenges and Future Trends. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 194–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A. (Ed.) Lightweight Ballistic Composites: Military and Law-Enforcement Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, M.A.; Boussu, F.; Bruniaux, P.; Hong, Y. Dynamic Impact Surface Damage Analysis of 3D Woven Para-Aramid Armour Panels Using NDI Technique. Polymers 2021, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirogiannis, E.C.; Daskalakis, E.; Vogiatzis, C.; Psarommatis, F.; Bartolo, P. Advanced Composite Armor Protection Systems for Military Vehicles: Design Methodology, Ballistic Testing, and Comparison. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 251, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, P.; Wu, L. A Novel Composite Material of Aramid Fiber-Reinforced Polyurea Elastomer Matrix: Mechanical Properties and Ballistic Performance. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 271, 111370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W. Recent Advancements in Ballistic Protection—A Review. J. Stud. Res. 2024, 13, 5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omerogullari Basyigit, Z. Functional Finishing for Textiles. In Researches in Science and Art in 21st Century Turkey; Gece Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2017; pp. 2297–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Abtew, M.A.; Boussu, F.; Bruniaux, P. Dynamic Impact Protective Body Armour: A Comprehensive Appraisal on Panel Engineering Design and Its Prospective Materials. Def. Technol. 2021, 17, 2027–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, R.; Agboola, O.; Mochane, M.; Fasiku, V.; Owonubi, S.; Ibrahim, I.; Abbavaram, B.; Kupolati, W.; Jayaramudu, T.; Uwa, C.; et al. The Use of Polymer Nanocomposites in the Aerospace and the Military/Defence Industries. In Handbook of Research on Polymer Nanocomposites for Advanced Engineering and Military Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Bello, A.; Adams, S.M.; Onwualu, A.P.; Anye, V.C.; Bello, K.A.; Obianyo, I.I. Nano-Enhanced Polymer Composite Materials: A Review of Current Advancements and Challenges. Polymers 2025, 17, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Sikdar, P.; Bhat, G.S. Recent Progress in Developing Ballistic and Anti-Impact Materials: Nanotechnology and Main Approaches. Def. Technol. 2023, 21, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulvel, S.; Reddy, D.M.; Rufuss, D.D.W.; Akinaga, T. A Comprehensive Review on Mechanical and Surface Characteristics of Composites Reinforced with Coated Fibres. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 27, 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanuprakash, L.; Parasuram, S.; Varghese, S. Experimental Investigation on Graphene Oxides Coated Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Hybrid Composites: Mechanical and Electrical Properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 179, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, S.; Nemati, A.; Khodabandeh, A.R.; Baghshahi, S. Investigation of Interfacial and Mechanical Properties of Alumina-Coated Steel Fiber Reinforced Geopolymer Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Liao, X.; Qin, Q.H.; Wang, G. The Fabrication and Characterization of High Density Polyethylene Composites Reinforced by Carbon Nanotube Coated Carbon Fibers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 121, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.; Jariwala, C.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, S. Process Optimisation of SiO2 Interface Coating on Carbon Fibre by RF PECVD for Advanced Composites. Surf. Interfaces 2017, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, H.Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, H.; Mai, Y.W.; Jia, Y.Y.; Yan, W. Glass Fibres Coated with Flame Synthesised Carbon Nanotubes to Enhance Interface Properties. Compos. Commun. 2021, 24, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.; Khalina, A.; Abdullah, N.; Aisyah, H.A.; Rafiqah, S.A.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Norrrahim, M.N.; Ilyas, R.A.; et al. A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite for Bullet Proof and Ballistic Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, A.C. Gelation. In Introduction to Sol-Gel Processing; Pierre, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 169–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; West, J.K. The Sol-Gel Process. Chem. Rev. 1990, 90, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bierwagen, G.P. Sol–Gel Coatings on Metals for Corrosion Protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 64, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriev, Y.; Ivanova, Y.; Iordanova, R. History of Sol-Gel Science and Technology. J. Univ. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2008, 43, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.D.; Sommerdijk, N.A. Sol-Gel Materials: Chemistry and Applications; CRC Press: Singapore, 2000; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Xu, P. Improving the Photo-Stability of High Performance Aramid Fibers by Sol-Gel Treatment. Fibers Polym. 2008, 9, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, S.; Kowalczyk, D.; Borak, B.; Jasiorski, M.; Tracz, A. Applying the Sol-Gel Method to the Deposition of Nanocoats on Textiles to Improve Their Abrasion Resistance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 3058–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, C.; Rinderer, B. Dyeing and DP Treatment of Sol-Gel Pre-Treated Cotton Fabrics. Fibers Polym. 2011, 12, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Cui, S. An Investigation on Sol–Gel Treatment to Aramid Yarn to Increase Inter-Yarn Friction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 320, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Rahman, M.R.; Min, S.; Chen, X. Experimental and Numerical Study of Inter-Yarn Friction Affecting Mechanism on Ballistic Performance of Twaron® Fabric. Mech. Mater. 2020, 148, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceratti, D.R.; Louis, B.; Paquez, X.; Faustini, M.; Grosso, D. A New Dip Coating Method to Obtain Large-Surface Coatings with a Minimum of Solution. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4958–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulding, E.A.; Diroll, B.T.; Goodwin, E.D.; Vrtis, Z.J.; Kagan, C.R.; Murray, C.B. Deposition of Wafer-Scale Single-Component and Binary Nanocrystal Superlattice Thin Films via Dip-Coating. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2846–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, M.; Doumenc, F.; Guerrier, B. Numerical Simulation of Dip-Coating in the Evaporative Regime. Eur. Phys. J. E 2016, 39, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseghai, G.B.; Malengier, B.; Fante, K.A.; Nigusse, A.B.; Van Langenhove, L. Development of a Flex and Stretchy Conductive Cotton Fabric via Flat Screen Printing of PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Conductive Polymer Composite. Sensors 2020, 20, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Yan, X. Dip-Coating for Fibrous Materials: Mechanism, Methods and Applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2017, 81, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmohammadsadeghi, S.; Juhas, D.; Parker, M.; Peranidze, K.; Van Horn, D.A.; Sharma, A.; Patel, D.; Sysoeva, T.A.; Klepov, V.; Reukov, V. The Highly Durable Antibacterial Gel-like Coatings for Textiles. Gels 2024, 10, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Rupanty, N.S.; Noor, T.; Asif, T.R.; Islam, T.; Reukov, V. Functional Coatings for Textiles: Advancements in Flame Resistance, Antimicrobial Defense, and Self-Cleaning Performance. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10984–11022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, D.M. Handbook of Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) Processing: Film Formation, Adhesion, Surface Preparation and Contamination Control; Knovel: Norwich, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, A.; Silva, F.; Porteiro, J.; Míguez, J.; Pinto, G. Sputtering Physical Vapour Deposition (PVD) Coatings: A Critical Review on Process Improvement and Market Trend Demands. Coatings 2018, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kumar, S.; Samal, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. A Review on Superhydrophobic Polymer Nanocoatings: Recent Development and Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 2727–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.; Gómez-Aleixandre, C. Review of CVD Synthesis of Graphene. Chem. Vap. Depos. 2013, 19, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, H.O. Fundamentals of Chemical Vapor Deposition. In Handbook of Chemical Vapor Deposition: Principles, Technology, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Materials Science and Process Technology Series; Noyes Publications: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 36–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, B.W.; Mitchell, D.J. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Zirconium Compounds: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, H.O. CVD Processes and Equipment. In Handbook of Chemical Vapor Deposition: Principles, Technology, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Materials Science and Process Technology Series; Noyes Publications: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 108–146. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Yan, X.-T. Chemical Vapor Deposition Systems Design. In Chemical Vapour Deposition; Engineering Materials and Processes; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 73–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinu, L.; Zabeida, O.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J.E. Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition of Functional Coatings. In Handbook of Deposition Technologies for Films and Coatings; Martin, P.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 392–465. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, S.G.; Greene, J.E. Plasmas in Deposition Processes. In Handbook of Deposition Technologies for Films and Coatings; Martin, P.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 32–92. [Google Scholar]

- Struszczyk, M.; Puszkarz, A.; Wilbik-Hałgas, B.; Cichecka, M.; Litwa, P.; Urbaniak-Domagała, W.; Krucinska, I. The Surface Modification of Ballistic Textiles Using Plasma-Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition (PACVD). Text. Res. J. 2014, 84, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struszczyk, M.H.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Miklas, M.; Wilbik-Hałgas, B.; Cichecka, M.; Urbaniak-Domagała, W.; Krucińska, I. Effect of Accelerated Ageing on Ballistic Textiles Modified by Plasma-Assisted Chemical Vapour Deposition (PACVD). Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2016, 24, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łandwijt, M.; Struszczyk, M.H.; Urbaniak-Domagała, W.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Wilbik-Hałgas, B.; Cichecka, M.; Krucińska, I. Ballistic Behaviour of PACVD-Modified Textiles. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2019, 27, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struszczyk, M.H.; Urbaniak-Domagała, W.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Wilbik-Hałgas, B.; Cichecka, M.; Sztajnowski, S.; Puchalski, M.; Miklas, M.; Krucińska, I. Structural Changes in the PACVD-Modified Para-Aramid Ballistic Textiles during the Accelerated Ageing. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2017, 25, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.E.; Routledge, T.J.; Lidzey, D.G. Advances in Spray-Cast Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittens, G.J. Variation of Surface Tension of Water with Temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1969, 30, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Baishya, H.; Gupta, R.; Garai, R.; Iyer, P. Thin Film Solution Processable Perovskite Solar Cell. In Perovskite Materials, Devices and Integration; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, W.; Zhai, W.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y.; Dong, B.; Wang, X. Enhancing Stab Resistance of Thermoset–Aramid Composite Fabrics by Coating with SiC Particles. J. Ind. Text. 2019, 48, 152808371876080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S.; Surendran, R.; Sekar, T.; Rajeswari, B. Ballistic Impact Analysis of Graphene Nanosheets Reinforced Kevlar-29. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, K.S.; Naik, N.K. Analytical and Experimental Studies on Ballistic Impact Behavior of Carbon Nanotube Dispersed Resin. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 76, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, P.; Ghosh, A.; Majumdar, A. Hybrid Approach for Augmenting the Impact Resistance of P-Aramid Fabrics: Grafting of ZnO Nanorods and Impregnation of Shear Thickening Fluid. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 13106–13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.S.; Mathur, V.; Asmatulu, R. Effect of Nanoclay and Graphene Inclusions on the Low-Velocity Impact Resistance of Kevlar-Epoxy Laminated Composites. Compos. Struct. 2018, 187, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusík, D.; Bocian, L.; Novotný, R.; Palovčík, J.; Hrbáčová, M. Influence of Fumed Nanosilica on Ballistic Performance of UHPCs. Materials 2023, 16, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Effects of Different Silica Particles on Quasi-Static Stab Resistant Properties of Fabrics Impregnated with Shear Thickening Fluids. Mater. Des. 2014, 64, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, V.; Stojanović, D.; Jancic Heinemann, R.; Zivkovic, I.; Radojevic, V.; Uskokovic, P.; Aleksic, R. Ballistic Properties of Hybrid Thermoplastic Composites with Silica Nanoparticles. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2014, 9, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, C.; Yildiz, S.; Güneş, M.; Senel, F.; Tanoglu, M. Stab and Ballistic Performances of Aramid Fabrics Impregnated with Silica Based Shear Thickening Fluids. Ömer Halisdemir Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 10, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, B. Nano-Projectiles Impact on Graphene/SiC Laminates. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 591, 153113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Loya, P.E.; Lou, J.; Thomas, E.L. Dynamic Mechanical Behavior of Multilayer Graphene via Supersonic Projectile Penetration. Science 2014, 346, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Fal′ko, V.I.; Colombo, L.; Gellert, P.R.; Schwab, M.G.; Kim, K. A Roadmap for Graphene. Nature 2012, 490, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.S.A.; Uddin, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Bipasha, F.A.; Hossain, S.S. Synthesis of Graphene. Int. Nano Lett. 2016, 6, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.; Goel, R.; Kaur, N.; Singh, M.K.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Understanding Behaviour of Graphene in Natural Fibre Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 232, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizao, R.A.; Machado, L.D.; de Sousa, J.M.; Pugno, N.M.; Galvao, D.S. Scale Effects on the Ballistic Penetration of Graphene Sheets. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugno, N.M.; Coluci, V.R.; Galvao, D.S. Nanotube- or Graphene-Based Nanoarmors. In Computational & Experimental Analysis of Damaged Materials; Pavlou, D.G., Ed.; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India, 2007; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dewapriya, M.A.N.; Meguid, S.A. Comprehensive Molecular Dynamics Studies of the Ballistic Resistance of Multilayer Graphene-Polymer Composite. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 170, 109171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, Y.Y.; Wen, X.; Jin, X.; Foller, T.; Joshi, R. Functional Groups in Graphene Oxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 26337–26355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Sisi, L.; Haiyan, Y.; Jie, L. Progress in the Functional Modification of Graphene/Graphene Oxide: A Review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 15328–15345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.B.; Parvaz, M.; Khan, Z.H. Graphene Oxide: Synthesis and Characterization. In Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudiki, A.; Matrouf, M.; Azriouil, M.; Laghrib, F.; Farahi, A.; Bakasse, M.; Lahrich, S.; El Mhammedi, M.A. Graphene Oxide Synthesized from Zinc-Carbon Battery Waste Using a New Oxidation Process Assisted Sonication: Electrochemical Properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 275, 125308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.O.; Weber, R.P.; Monteiro, S.N.; Lima, A.M.; Faria, G.S.; da Silva, W.O.; Oliveira, S.S.A.; Monsores, K.G.C.; Pinheiro, W.A. Effect of Graphene Oxide Coating on the Ballistic Performance of Aramid Fabric. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukle, S.; Valisevskis, A.; Briedis, U.; Balgale, I.; Bake, I. Hybrid Soft Ballistic Panel Packages with Integrated Graphene-Modified Para-Aramid Fabric Layers in Combinations with the Different Ballistic Kevlar Textiles. Polymers 2024, 16, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, U.O.; Nascimento, L.; Garcia, J.; Monteiro, S.N.; Luz, F.; Pinheiro, W.; Garcia Filho, F.C. Effect of Graphene Oxide Coating on Natural Fiber Composite for Multilayered Ballistic Armor. Polymers 2019, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidhendi, M.R.T.; Behdinan, K. Graphene Oxide Coated Silicon Carbide Films under Projectile Impacts. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 261, 108662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, W. Laser Induced Graphene for EMI Shielding and Ballistic Impact Damage Detection in Basalt Fiber Reinforced Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 242, 110182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, K.; Groo, L.; Sodano, H.A. Laser Induced Graphene for In-Situ Ballistic Impact Damage and Delamination Detection in Aramid Fiber Reinforced Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 202, 108551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliana-Cervera, G.; Mattia, D.; Pasquino, C.; Veness, R.; Lunt, A.J.G. Carbon Nanotube Wires for Accelerator Applications. Mater. Des. 2025, 258, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Sehrawat, M.; Sharma, S.; Bharadwaj, S.; Chauhan, G.S.; Dhakate, S.R.; Singh, B.P. Carbon Nanotube-Based Soft Body Armor: Advancements, Integration Strategies, and Future Prospects. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 148, 111446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Fang, S.; Sun, Y. Shear-Thickening Fluid Using Oxygen-Plasma-Modified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes to Improve the Quasi-Static Stab Resistance of Kevlar Fabrics. Polymers 2018, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, D.; Vricella, A.; Pastore, R.; Delfini, A.; Giusti, A.; Albano, M.; Marchetti, M.; Moglie, F.; Primiani, V.M. Ballistic and Electromagnetic Shielding Behaviour of Multifunctional Kevlar Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composites Modified by Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2016, 104, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, E.; Xu, Z. Interfacial Failure Boosts Mechanical Energy Dissipation in Carbon Nanotube Films under Ballistic Impact. Carbon 2019, 146, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Hanif, W.Y.; Risby, M.S.; Noor, M.M. Influence of Carbon Nanotube Inclusion on the Fracture Toughness and Ballistic Resistance of Twaron/Epoxy Composite Panels. Procedia Eng. 2015, 114, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soorya Prabha, P.; Ragavi, I.G.; Rajesh, R.; Pradeep Kumar, M. FEA Analysis of Ballistic Impact on Carbon Nanotube Bulletproof Vest. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 3937–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirogiannis, E.C.; Daskalakis, E.; Hassan, M.H.; Omar, A.M.; Bartolo, P. Ballistic Design and Testing of a Composite Armour Reinforced by CNTs Suitable for Armoured Vehicles. Def. Technol. 2024, 32, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Xiao, K.; Huang, C.; Wu, X. Dynamic Behavior of Tunable Bouligand-Structured Carbon Nanotube Films under Micro-Ballistic Impact. Nano Mater. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, K.; Hu, D.; Huang, C.; Wu, X. Anomalous Size Effect of Impact Resistance in Carbon Nanotube Film. Mater. Today Adv. 2024, 24, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Pang, H.; Zhao, C.; Xuan, S.; Gong, X. The CNT/PSt-EA/Kevlar Composite with Excellent Ballistic Performance. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 185, 107793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonieczna-Dąbrowska, P.; Wróblewski, R.; Płocińska, M.; Leonowicz, M. Impact of the Carbon Nanofillers Addition on Rheology and Absorption Ability of Composite Shear Thickening Fluids. Materials 2020, 13, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBarre, E.D.; Calderon-Colon, X.; Morris, M.; Tiffany, J.; Wetzel, E.; Merkle, A.; Trexler, M. Effect of a Carbon Nanotube Coating on Friction and Impact Performance of Kevlar. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 5431–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Cao, S.; Wang, S.; Bai, L.; Sang, M.; Xuan, S.; Jiang, W.; Gong, X. CNT/STF/Kevlar-Based Wearable Electronic Textile with Excellent Anti-Impact and Sensing Performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 126, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiwar, D.; Verma, S.K.; Gupta, N.; Agnihotri, P.K. Augmenting the Fracture Toughness and Structural Health Monitoring Capabilities in Kevlar/Epoxy Composites Using Carbon Nanotubes. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 297, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, S.; Lu, X.; Ma, J.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Ba, S. Preparation and Characterization of Shear Thickening Fluid/Carbon Nanotubes/Kevlar Composite Materials. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 3146–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-S.; Malakooti, M.H.; Sodano, H.A. Tailored Interyarn Friction in Aramid Fabrics through Morphology Control of Surface Grown ZnO Nanowires. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 76, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y.C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, G.Y. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Ballistic Performance of a ZnO-Modified Aramid Fabric. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 175, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Min, S.; Chen, H.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, T.; Chen, X. Research on High-Velocity Ballistic Impact of Para-Aramid Sateen Fabric with ZnO Nanorods Oriented to the Development of Soft Body Armor. Mater. Des. 2024, 248, 113384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, B.; Srinu, G.; Balaganesan, G. Effects of ZnO Nanowire and Silica Coatings on the Inter-Yarn Friction and Ballistic Properties of Kevlar Fabrics. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 178, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakooti, M.H.; Hwang, H.-S.; Goulbourne, N.C.; Sodano, H.A. Role of ZnO Nanowire Arrays on the Impact Response of Aramid Fabrics. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, K.; Sodano, H.A. Improved Inter-Yarn Friction and Ballistic Impact Performance of Zinc Oxide Nanowire Coated Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE). Polymer 2021, 231, 124125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, N.E.; Erdogan, G.; Bilisik, K. Pull-Out Properties of Nano-Processed Para-Aramid Fabric Materials in Soft Ballistic: An Experimental Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lan, Z.; Deng, J.; Xu, Z.; Nie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Hao, H. Enhanced Interfacial Properties of Carbon Nanomaterial–Coated Glass Fiber–Reinforced Epoxy Composite: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Front. Mater. 2022, 8, 828001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chang, C.; Anbalagan, A.; Tai, N.-H. Reduced Graphene Oxide/Zinc Oxide Coated Wearable Electrically Conductive Cotton Textile for High Microwave Absorption. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 188, 107994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panth, M.; Cook, B.; Alamri, M.; Ewing, D.; Wilson, A.; Wu, J.Z. Flexible Zinc Oxide Nanowire Array/Graphene Nanohybrid for High-Sensitivity Strain Detection. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 27359–27367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arat, R.; Jia, G.; Plentz, J. Wet Chemical Method for Highly Flexible and Conductive Fabrics for Smart Textile Applications. J. Text. Inst. 2023, 114, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghizadeh, A.; Khoramishad, H.; Jalaly, M. Effect of Graphene Oxide–Iron Oxide Hybrid Nanocomposite on the High-Velocity Impact Performance of Kevlar Fabrics Impregnated with Nanosilica/Polyethylene Glycol Shear Thickening Fluid. J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2023, 237, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class of Materials | Material | Characteristic Properties | Typical Range of Key Physical Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals | Armox 500T | High-strength ballistic steel; Good combination of strength and toughness; Used for ballistic protection applications. | Hardness: 480–540 HB; Yield strength: 1200–1600 MPa; Density: 7.8 g/cm3 | [20,21,22,23,24] |

| Hardox 450 | High hardness and abrasion resistance; Superior ductility and toughness; Suitable for ballistic barriers and hybrid armor systems. | Hardness: ~450 HB; Yield strength: 1200 MPa; Density: 7.85 g/cm3 | [21,22,23,24,25] | |

| PROTAC 500 | High-strength steel used in ballistic applications; Recognized for strength and toughness. | Hardness: ~480 HB; Yield strength: 1300–1500 MPa | [20,21,22,23,24] | |

| Ceramics | Al2O3 (Alumina) | High hardness, stiffness, thermal resistance, environmental stability; Low cost and good manufacturability. | Hardness: 14–20 GPa; Density: 3.8–3.95 g/cm3; Elastic modulus: 300–400 GPa | [27,28,29,30,31,32] |

| SiC (Silicon Carbide) | Lower density than alumina; Higher hardness and fracture strength than alumina; Ballistic performance close to B4C but with much lower cost; Intermediate balance between cost, toughness, manufacturability, and ballistic efficiency. | Hardness: 22–28 GPa; Density: 3.15–3.25 g/cm3; Elastic modulus: 380–420 GPa | [30,31,33,36] | |

| B4C (Boron Carbide) | Extremely low density, very high hardness, highest ballistic efficiency; Limitation: stress-induced amorphization decreases shear strength and ballistic resistance; Amorphization controlled by composition and microstructure. | Hardness: 30–38 GPa; Density: 2.48–2.52 g/cm3; Elastic modulus: 450–470 GPa | [30,31,32,33,34,35] | |

| Polymers | Kevlar | Low density: ~1.44 g/cm3; High tensile strength and high elastic modulus; High strength-to-weight ratio, approx. five times stronger than steel on equal weight basis; Large failure strain and efficient in-plane energy distribution (fibrillation + fiber stretching); Excellent chemical stability, low thermal expansion, good dimensional stability, high rigidity. High flexibility, enabling comfort and mobility in soft armor; Exceptional ballistic performance, significantly enhanced when impregnated with STF. | Density: 1.44 g/cm3; Tensile strength: 2.8–3.6 GPa; Modulus: 70–130 GPa; Failure strain: 2.5–4% | [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] |

| UHMWPE | Very low density: ~0.93 g/cm3/970 kg/m3; Extremely high strength-to-weight ratio; Tensile strength: 2.4–4.0 GPa; Specific strength 30–40% higher than aramid fibers; Very high molecular weight: 2–6 million g/mol; Failure strain: 3.8% (vs. aramid 3.6%); Tenacity: 3.7 N/tex (vs. aramid 2.4 N/tex); ≈25% higher ballistic performance than aramid at equal areal density; Excellent energy absorption capability. | Density: 0.93–0.97 g/cm3; Tensile strength: 2.4–4.0 GPa; Modulus: 80–120 GPa; Failure strain: 3.5–4% | [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] | |

| Composite | AA2024 metal matrix composite reinforced with MWCNTs (MMC–CNT) | Enhanced mechanical behavior compared to conventional backplates; Superior ballistic performance under STANAG Level 4 testing; Reduced weight relative to standard metallic backplates; Higher kinetic energy absorption. | Density: 2.75–2.80 g/cm3; Tensile strength (reinforced): 500–600 MPa; Modulus: 70–80 GPa | [82] |

| Coating Type | Uncoated Baseline Material | Improved Property | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanosilica (STF impregnation and surface coatings) | Kevlar KM2, Kevlar fabrics, Twaron | Increased energy absorption, higher inter-yarn friction, improved puncture and ballistic resistance, preserved flexibility | [48,137,138] |

| Graphene/Graphene Oxide (GO) | Kevlar KM2, Kevlar XP, para-aramid fabrics | Enhanced tensile strength and toughness, improved interfacial adhesion, higher absorbed energy (up to +50%), reduced number of layers required, increased thermal stability | [5,75,147,148,149,150,151] |

| Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) | Cotton fabric and polyamide fabric (depending on study) | Improved energy absorption, EMI shielding efficiency (~50 dB), multifunctionality (self-sensing and impact detection) | [156,157] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Kevlar KM2 and Twaron CT747 | Increased tensile strength (up to +46%), improved inter-yarn friction, higher ballistic limit (+50%), energy absorption (+240%), multifunctional capabilities (smart textiles) | [168,169,170,171,172,173] |

| ZnO Nanowires | Kevlar KM2 and Twaron fabrics | Enhanced inter-yarn friction, higher pull-out energy (+822.9%), improved impact resistance (+66%), increased ballistic performance (V50 +59.1%), with negligible weight increase | [176,177,178] |

| Coating Methods | Coating Materials | Substrate | Reported Ballistic Improvement | Mechanism of Enhancement | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dip–Pad–Dry method (sol–gel method) | TiO2/ZnO hydrosols (submicrometric vs. nanometric particles) | Twaron aramid fibers | CSF = 0.1617 and CKF = 0.1554; Tensile strength reduction < 10%; Reduction in strain and modulus < 5%; Weight increase ~4% without curing; ≈0% or slight decrease with curing. | Rougher surface with “lump-like” features (submicron) or “film-like” coating (nano); Improved ballistic performance potential. | [105] |

| TiO2/ZnO submicron hydrosol | Twaron® yarns and fabric | Inter-yarn friction increased by more than 20%, with the CSF 0.1991 and the CKF 0.1871; The energy absorption increased by more than 35% under impact velocities of 450–500 m/s. | A significantly rougher yarn surface, forming lump-like structures that enhanced mechanical interlocking between yarns; Higher ballistic energy absorption. | [106] | |

| Soaking method | SiO2 NPs 500 nm (15, 25, 35, and 45 wt.%) in polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Kevlar fabrics (2- and 4-layers) | STF impregnation increased energy absorption; 35 wt.% nanosilica yielded the highest specific energy absorption; Ballistic resistance improved from 15 to 35 wt.% nanosilica; Only marginal improvement from 35 to 45 wt.%; Pull-out force increased consistently with higher nanoparticle content. | Improved impact resistance, reduced yarn pull-out, and more efficient multilayer interaction during impact. | [48] |

| STFs were prepared by dispersing fumed silica nanoparticles | Aramid fabrics Twaron TM (CT709) | Higher silica loading increased stab and ballistic resistance, with 30% SiO2 giving the best overall performance; At this concentration, the shear-thickening response was maximized, stab resistance improved the most, and penetration resistance of STF-impregnated aramid also reached its peak. | Silica-based STFs enhance energy absorption and penetration resistance; higher silica loading strengthens shear thickening, enabling rapid impact stiffening and better protection. | [139] | |

| Coating method | Modified SiO2 NPs in PVB/ethanol sol | p-aramid fiber type Twaron | Stopped all bullets; only back-face deformation observed. | Nanosilica stiffening, better energy dissipation, reduced yarn pull-out. | [138] |

| Vacuum filtration method | Graphene oxide (GO) | Twaron® textile | The ballistic resistance of the aramid fabric increases with the deposition of GO by values up to 50% higher than those for the as-received fabric. | Increase in ballistic resistance. | [152] |

| Impregnation method | CNT/PSt-EA-based shear-thickening fluid (C-STF) | Kevlar plain-weave fabric | Ballistic limit improved from 84.6 m/s to 96.5 m/s with C-STF impregnation; Optimum CNT content (1.0%) increased V50 to 96.5 m/s; excessive CNT reduced performance; Increasing STF dispersed-phase volume (53.5% to 58.5%) raised V50 from 92.9 to 99.5 m/s. | Increased inter-yarn friction and enlarged bearing area due to C-STF doping, improving energy dissipation and impact resistance. | [168] |

| Ultrasonication-assisted treatment method | MWNTs dispersed in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | Kevlar K129 yarns and Kevlar K129 fabrics | 50% increase in ballistic limit with MWNT treatment (mass increase only 0.4–1.4%). | MWNT coating increases fiber–fiber interaction and friction, enhancing energy transfer and reducing yarn pull-out at impact. | [170] |

| “soak and dry” method | STF based on SiO2 nanoparticles (71 wt%) dispersed in PEG 200 STF with various loadings (15%, 55%, 75%) | Kevlar fabric | STF-15%/Kevlar showed 200% improvement in impact resistance; STF-55%/Kevlar showed superior puncture resistance versus neat Kevlar; STF/Kevlar (15%, 55%, 75%) outperformed neat Kevlar at all energies tested (8.6–17.2 J); STF/Kevlar penetration depth significantly decreased with increasing STF content. | Higher STF viscosity increases inter-yarn friction and impact stiffening, forming a viscous network that improves load transfer and reduces penetration, while PEG alone acts as a lubricant, confirming friction enhancement as the key protection mechanism. | [171] |

| Dip coating (3×) + hydrothermal ZnO nanowire growth | ZnO nanoparticles + ZnO nanowires | Aramid (Kevlar) fabric | Elastic modulus increased by 8.8% (from 61.88 to 67.36 GPa). Tensile strength increased by 13.2% (≈2.49 GPa); Peak impact load increased from 1268 N to 2107 N (≈66%); Prevention of projectile penetration in the 30–34 m/s window; Yarn pull-out resistance increased (up to +985% at peak pull-out load). | Increased fiber and yarn friction; Limited yarn mobility; nanowires fill crossovers; Enhanced surface roughness; Improved load transfer and energy dissipation. | [178] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alexe, G.G.; Carp, G.B.; Tiganescu, T.V.; Buruiana, D.L. Enhancing the Performance of Materials in Ballistic Protection Using Coatings—A Review. Technologies 2026, 14, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010013

Alexe GG, Carp GB, Tiganescu TV, Buruiana DL. Enhancing the Performance of Materials in Ballistic Protection Using Coatings—A Review. Technologies. 2026; 14(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexe, Georgiana Ghisman, Gabriel Bogdan Carp, Tudor Viorel Tiganescu, and Daniela Laura Buruiana. 2026. "Enhancing the Performance of Materials in Ballistic Protection Using Coatings—A Review" Technologies 14, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010013

APA StyleAlexe, G. G., Carp, G. B., Tiganescu, T. V., & Buruiana, D. L. (2026). Enhancing the Performance of Materials in Ballistic Protection Using Coatings—A Review. Technologies, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010013