1. Introduction

Multi-stage planetary gear transmission systems are widely used in applications such as electric wheels for vehicles and high-speed heavy-duty machinery due to their compact structure, high power density, wide range of gear transmission ratios, and power splitting capabilities. Lubrication conditions of gear and bearing characteristics under a high-speed operation condition would significantly impact the working performance of multi-stage planetary gear transmission systems; to be more specific, this would depend on whether or not the lubricating oil precisely reaches the heat generation parts and work effectively. In such transmission systems, lubrication oil passages are typically integrated within the rotating shaft to ensure comprehensive lubrication efficacy. These oil passages rotate synchronously with the shaft, utilizing centrifugal force to distribute the lubricating oil, thereby enabling its delivery to all necessary components within the system. For multi-stage planetary transmission systems, the lubrication oil supply system not only involves the absolute rotation of the main shaft and each planetary gear set but also the relative rotation between the main shaft and the planetary gears, which would create complex fluid flow behavior in the rotating-stationary interface region. However, under the operational boundaries of the multi-stage planetary gearbox lubrication system, it is critical to determine which factor—lubricant oil temperature, supply pressure, or inter-stage rotational speed—predominantly influences performance. Therefore, studying the flow behaviors and oil supply characteristics in multi-planetary gear systems holds significant practical application value.

Investigations on oil flow supply characteristics of multi-stage planetary transmission systems typically involve liquid flow behaviors inside rotating passages and the lubrication of gears and bearings inside gearboxes (fixed-axle gearboxes and single-stage or multi-stage planetary gearboxes). Aiming at this topic, researchers have carried out a lot of works, which demonstrates the potential of numerical and experimental methods for solving key challenges of the present work.

Some studies have been performed on the fluid flow behaviors inside rotating oil passages. Numerical investigations by Chang et al. [

1] of two-phase flow in an axially rotating passage indicated that their model can be considered as an effective tool for simulating the liquid phase motion. However, the structural model is relatively simplistic and does not account for the complex flow regimes within the multi-stage transmission lubrication system. Using large eddy simulation (LES), Abdi et al. [

2] found that the centrifugal force induced by rotation would lead to an increase in the average axial velocity of the fluid within a rotating passage. Yet, it does not account for the branched structure of the lubrication passages or the flow field interactions resulting from inter-stage rotational speed differentials in multi-stage transmission systems. Bochkarev et al. [

3] studied the stability of fluid motion inside a rotating passage under different rotational speeds and observed that flow velocity was influenced by changes in both the structural size and boundary conditions. Nevertheless, it fails to consider fluid perturbations induced by the lubrication passage boundaries and the dynamic distribution of oil flow within the multi-stage planetary gear sets. Gao [

4] employed CFD simulations to examine the lubricant flow characteristics in the passages of a rotating machinery lubrication system. However, it does not account for flow partitioning resulting from differential rotational speeds between stages or the associated flow field inhomogeneities induced by these inter-stage speed differentials within the multi-stage planetary transmission system. Kim et al. [

5] investigated the effects of inlet pressure and flow rate variations on the outlet flow characteristics of rotating passages and found that at sufficiently high rotational speeds, the flow developed into an annular pattern. In spite of this, it does not address the flow resistance and perturbations imposed by the branched structure and inter-stage structures on oil distribution within the multi-stage transmission system. Guerrero et al. [

6] investigated the causes and effects of backflow in a turbulent passage flow using direct numerical simulations. Ceci et al. [

7] employed a direct numerical simulation, demonstrating that the flow characteristics in rotating pipes were governed by complex interactions among rotational speed, inertial forces, and viscous forces.

About the lubrication of gears and bearings inside gearboxes, Shi et al. [

8] employed a VOF multi-phase model coupled with the SST k-ω turbulence model to conduct CFD simulations of oil–water two-phase flow in horizontal pipes with high viscosity ratios. Their study analyzed the effects of wall contact angle, initialization methods, and volume fraction discretization schemes on numerical results. Deng et al. [

9] studied the effects of parameters including oil viscosity, immersion depth, turbine rotational speed, worm arrangement angle, and oil groove volume on the lubrication performance of a high-precision roller enveloping reducer. Yet, it does not consider the influence of inter-stage rotational speed differentials on oil flow distribution and lubrication performance within the planetary transmission system. Boni et al. [

10] investigated the flow characteristics in splash-lubricated planetary gear sets under conditions where an oil ring fails to form. They experimentally examined various oil volumes, temperatures, and input speeds, thereby determining the critical oil quantity required for oil ring formation and characterizing the associated flow regimes. In contrast, the analysis focuses on churning losses and flow regime characterization, without addressing forced lubrication in the multi-branch oil supply passage of multi-stage planetary transmission systems. Liu et al. [

11] established an experimental platform for oil–gas two-phase flow to investigate the behavior in vertical vent pipes of aero-engines. Their study analyzed the effects of the oil supply rate, air supply rate, and pipe diameter on flow patterns. Zhou et al. [

12] developed a jet lubrication model for a high-speed helical gear to evaluate the lubrication performance based on the oil volume fraction and oil pressure. However, it does not address the combined effects of the multi-branch lubrication passage and inter-stage rotational speed differentials on jet lubrication efficacy, thereby limiting its direct applicability to spray parameter analysis in three-stage planetary transmission systems. Mastrone et al. [

13] presented a CFD model of a two-stage industrial reducer within the open-source framework OpenFOAM

®, addressing boundary motion in multi-stage gearboxes. In spite of this, the study focuses on a two-stage industrial gearbox and does not consider the substantial flow field perturbations induced by pronounced inter-stage speed differentials in three-stage systems. Mastrone et al. [

14] performed a numerical analysis on the lubrication performance of a planetary gearbox using a finite-volume-based re-meshing strategy implemented in the open-source code OpenFOAM

® to investigate the flow characteristics within the rotating oil passages of a helicopter’s variable-speed transmission. But, the adaptability of its mesh strategy to the complex flow field of the three-stage system has not been verified, and thus it cannot be directly applied to the accurate analysis of the system’s lubrication performance. Hu et al. [

15] first established a model of a two-stage system with a single inlet and multiple branched outlets and validated this simulation methodology through experimental measurements. Yet, its oil passage structure is a two-stage transmission mechanism without different inter-stage rotational speeds. Meanwhile, the testing mechanism in its experimental bench has been correspondingly simplified, and the experimental operating conditions are not sufficient. Shao et al. [

16] performed a CFD study on a two-stage herringbone gearbox with an idler in a high-speed train to investigate the impacts of gear rotational speed, lubricant volume, and temperature on oil flow, film distribution, and lubrication conditions in the meshing zone. Hildebrand et al. [

17] conducted a combined numerical, experimental, and analytical investigation of oil flow in a dip-lubricated single-stage gearbox. In spite of this, its research object is a single-stage gearbox, and it does not involve the complex effects of the multi-branch oil circuits and inter-stage speed differences of the three-stage system on the oil flow. Chen et al. [

18] simulated the practical lubrication behavior of planetary gear journal bearings (PGJBs) in high-power wind turbines and performed experiments on a full-scale PGJB test bench. The experimental results demonstrated consistent agreement with numerical predictions. In contrast, the study focuses on the lubrication of planetary gear journal bearings—a single component—and does not address the overall passage design and oil flow distribution in multi-stage planetary transmissions, thereby limiting its direct applicability to the design of integrated lubrication systems for such systems.

Previous studies on liquid flow characteristics in rotating oil passages primarily addressed turbulent flow states within single rotating pipe segments. Moreover, experimental studies in previous research predominantly focused on oil distribution patterns captured by high-speed cameras in splash-lubricated or jet-lubricated gearboxes. However, investigations into the lubricating oil supply volume, which is a critical parameter affecting lubrication performance, are still insufficient. Furthermore, most existing studies pay more attention to single-stage planetary transmission systems. Owing to the limited computational capacity and the complexity of CFD simulation models, few studies have explored lubrication in two-stage planetary transmission systems, let alone more complex planetary transmission systems. The present study investigates a three-stage planetary transmission system of a large tracked vehicle and performs CFD analysis considering both the rotational dynamics of the entire oil passage and the relative motion of planetary gear sets under different gear ratios. The experiments are conducted on a specially made test bench to validate the numerical methods by comparing between numerical and experimental oil supply volumes. Furthermore, the lubrication performance of the overall oil passages of the three-stage planetary transmission is evaluated under varying influential parameters.

2. Numerical Methods

In this research, the effect of oil temperature heating is not considered during experimental validation. Numerical simulations are performed using CFD methods to discretize the flow field and obtain corresponding numerical solutions. The fluid flow is governed by the conservation of mass and momentum, which yields the continuity equation and the Navier–Stokes equations as the governing equations.

The continuity equation, which applies the principle of mass conservation to fluid flow models, serves as a governing equation for fluid motion. It asserts that the mass flow rate entering and exiting a fluid element must be equal, as expressed by the following equation:

where

is the density,

is time,

,

, and

are the velocity toward the

,

, and

directions, (

is commonly denoted as

, and

is the velocity vector field.

The fluid momentum equation conforms to Newton’s second law, whereby the product of a fluid element’s mass and its acceleration equals the total force acting upon it. These forces comprise both body forces and surface forces, as expressed by the following equation:

where

is the pressure,

is the stress in the

direction acting on the plane perpendicular to the

axis, and

is the body force per unit mass acting on the fluid element.

In this work, the flow of lubricating oil in the oil passages is categorized as viscous flow. Its flow state typically involves pipeline losses due to frictional resistance and variations in pipe diameter. For the simplification and analysis of the lubricating oil passage, it satisfies the Bernoulli equation [

4], which is specifically expressed as follows. Meanwhile, Bernoulli’s equation is used for conceptual illustration only and is not applied in the CFD solver.

where

is the position head,

is the pressure head,

is the velocity head,

is the along-the-line loss,

is the local loss,

is the friction coefficient,

is the pipe length,

is the pipe diameter, and

is the local resistance coefficient.

2.1. Turbulence Model

This section is organized with subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results and their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The turbulence model employed in this study is the κ-ε model, a two-equation approach based on the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, which solves two separate transport equations. The standard κ-ε model is a high-Reynolds-number formulation, valid for fully developed turbulent flows but neglecting molecular viscosity—thus rendering it inapplicable in regions such as near-wall zones where turbulence is not fully developed. To address this limitation, the RNG and realizable κ-ε models were introduced. The SST k–ω model is more accurate and reliable for adverse pressure gradient flows, airfoils, and transonic shock waves in fields such as aerospace, automotive engineering, and turbomachinery, whereas the RNG k–ε model is more appropriate for the turbulent flow of lubricating oil in pipelines. The RNG model incorporates an additional term in the dissipation rate equation, improving accuracy for flows with rapid strain. In the present work, the lubrication oil passage operates at high rotational speeds, where centrifugal forces induced by vortices enhance circumferential turbulence intensity near the wall. Consequently, the RNG κ-ε model is adopted as the turbulence model herein. The corresponding transport equations are given below, where

is the correction term for different

values.

where

is the kinetic energy released during turbulence due to the mean velocity gradients,

is the amount of kinetic energy generated by buoyancy effects in turbulence,

is the amount of variable dilatation in compressible turbulence that contributes to the total rate of dissipation,

and

are the inverse effective Prandtl numbers for turbulence kinetic energy and the turbulence dissipation rate, respectively,

and

are custom source items,

,

,

.

2.2. Multi-Phase Flow Model

The lubrication of the multi-stage planetary gear sets, bearings, and other components in a tracked vehicle’s multi-stage planetary transmission involves gas–oil two-phase flow during startup and operation. To track the oil–air interface under dynamic rotating conditions, the Volume-of-Fluid (VOF) method is employed. Within the computational domain, the volume fractions of lubricating oil and air maintain a fixed relative proportion, and their sum remains in unity [

8]. The governing equations are expressed as follows:

where

and

are the air and lubricating oil volume portions. If

is 0, it indicates that the unit is filled with lubricating oil; if

is 0, it indicates that the unit is filled with air; otherwise, it indicates a state where lubricating oil and air coexist.

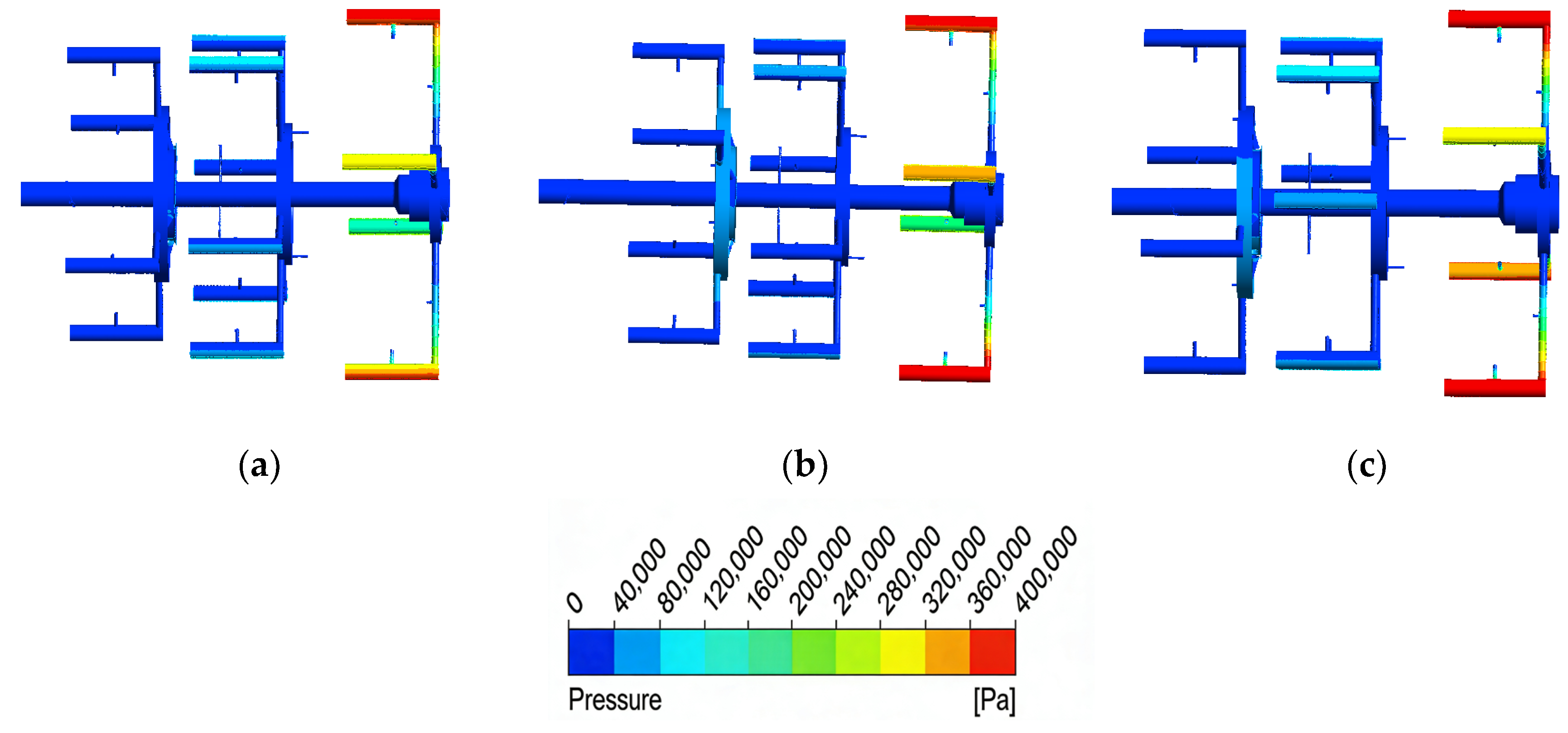

3. Validation of the Numerical Methods

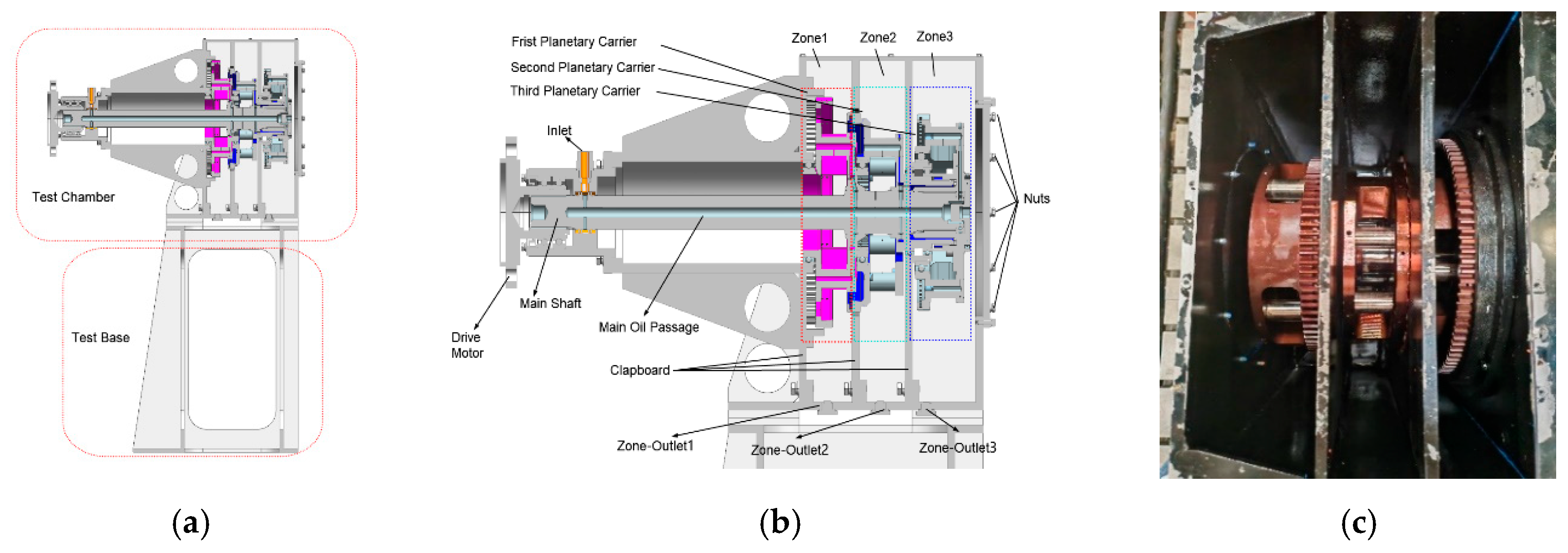

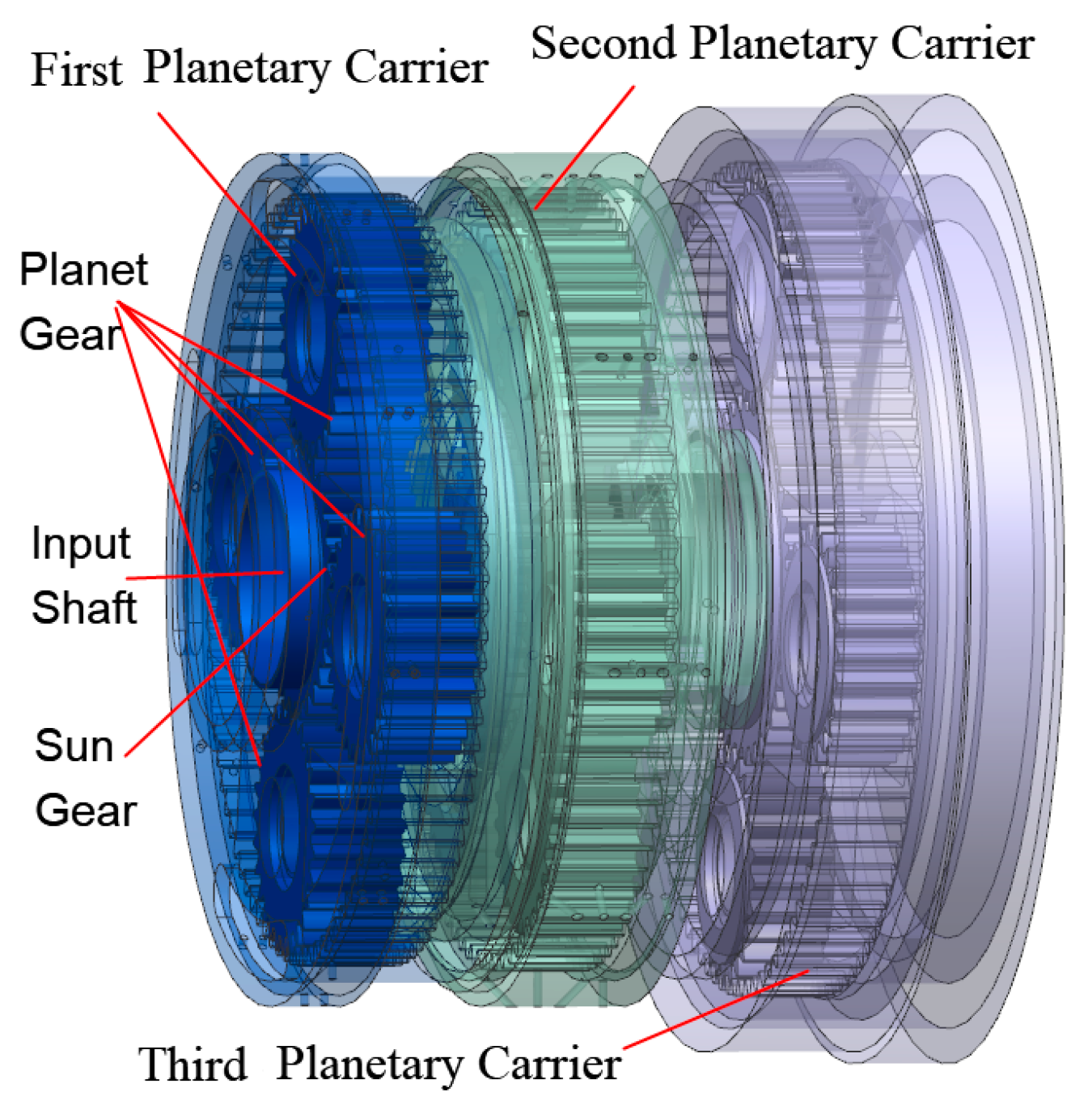

To validate the numerical methods employed for analyzing the oil supply characteristics of the multi-stage planetary transmission system, experiments are conducted on a dedicated test bench, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The test bench primarily consists of key components such as an oil reservoir, a motor, oil pumps, filters, flow meters, and pressure-regulating valves. The lubrication pump station adjusts the oil supply pressure and flow rate. Measuring cups are positioned at the outlet ports corresponding to each planetary gear set within the test assembly to collect oil discharge volumes for quantitative comparison. The configuration of the multi-stage planetary gear test assembly is illustrated in

Figure 2. The rotational speed of the planetary carriers is controlled by a drive motor connected to the main shaft. The carriers are mounted within three separate compartments in the test gearbox, each partitioned by baffles. A 16 mm diameter oil outlet is located at the bottom of each compartment, and the connected tubing and measuring cups are used to collect and quantify the drained oil. In this experiment, the measuring cup used has a range of 5000 mL with a permissible error of ±10 m. Detailed experimental parameters are provided in

Table 1.

To compare the numerical results with experimental ones, first, a grid independence study was conducted to ensure that the computational results were unaffected by mesh discretization, thereby enhancing simulation reliability. Three mesh sizes—0.8 mm, 1.2 mm, and 1.6 mm—were evaluated by comparing the deviation between the inlet and total outlet flow rates. As the mesh was refined, this deviation decreased, with the relative error falling below 0.2%. Considering both computational accuracy and cost, a mesh size of 1.2 mm was selected as the optimal configuration. The grid independence analysis data are presented in

Table 2. Furthermore, in simulations, the number of fluid domain elements is equal 2,787,983, with an orthogonal quality exceeding 0.2005 and an element quality greater than 0.21648, meeting the requirements for accurate fluid dynamic computations.

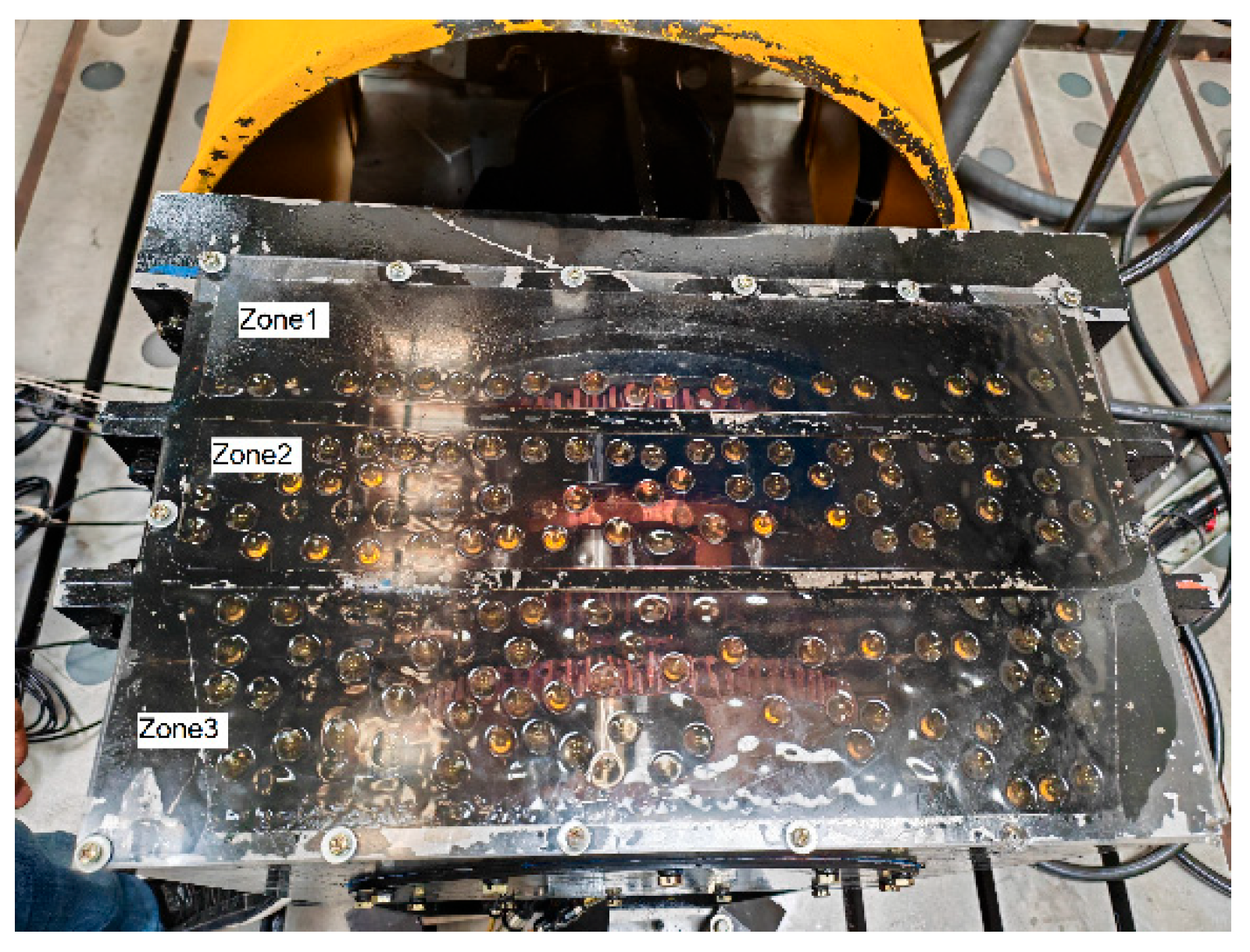

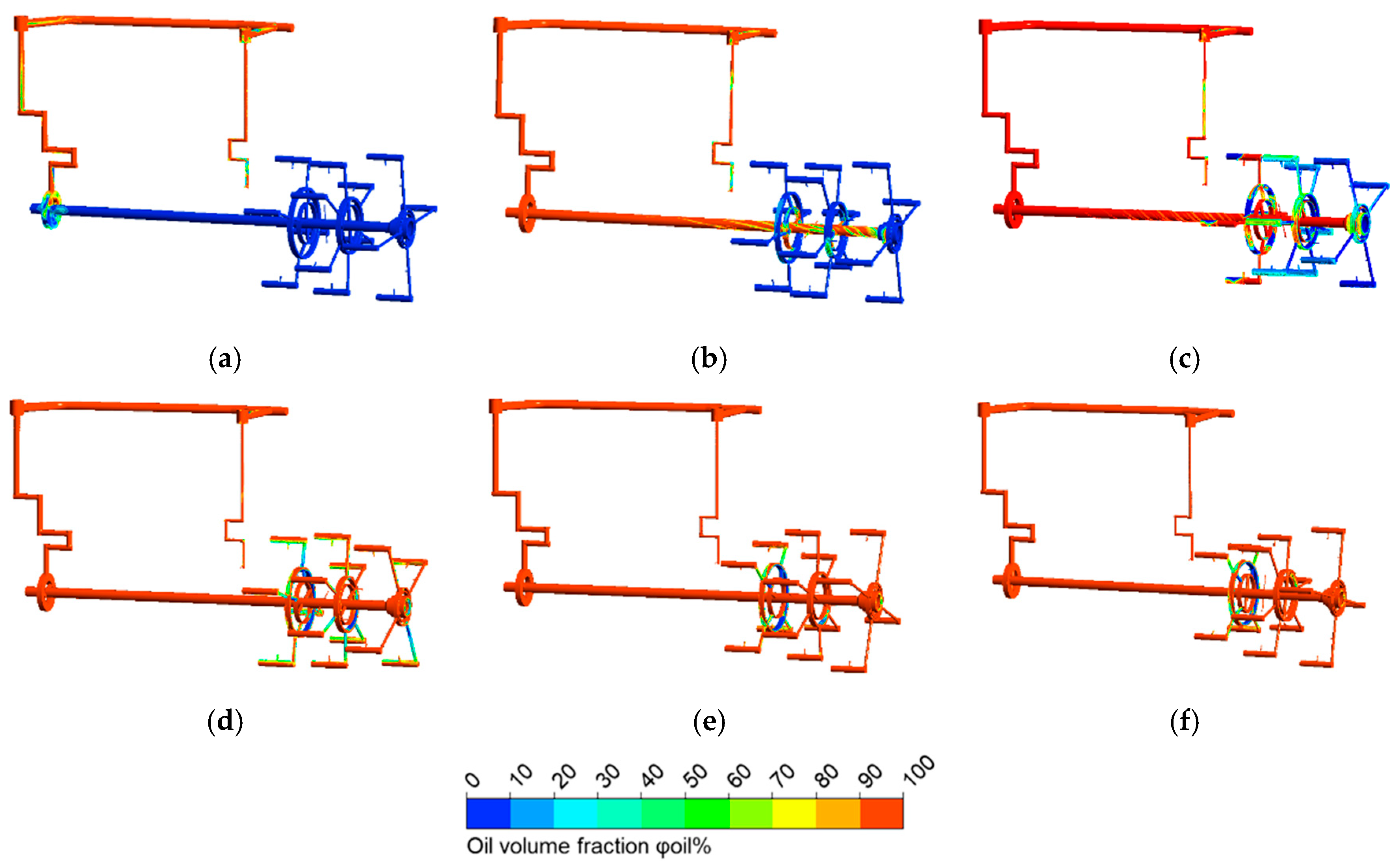

The experimental procedure is described as follows: first, the drive motor is activated, and the main shaft begins to rotate. The first-stage planetary carrier remains stationary at 0 rpm, while the second- and third-stage carriers rotate at the same speed as the main shaft. The oil pump is then engaged to circulate lubricant through all planetary stages. Following a 20 s operational period of the drive motor, the test bench underwent oil supply cessation and system shutdown. Oil flow was subsequently collected over a 10 min interval until the volume in the measuring cups stabilized, indicating the attainment of steady-state conditions. After the oil flow reaches a steady state, the discharged lubricant is collected via three measuring cups (called Cup 1, Cup 2, and Cup 3, respectively) connected to the outlet ports at the bottom of the three compartments, as shown in

Figure 3. For each oil pressure and rotational speed condition, data are acquired over a 20 s interval, with each measurement repeated three times. After data recording, the oil from the measuring cups is returned to the pump reservoir, and this procedure is repeated until all experimental conditions are tested. As shown in

Figure 4, three compartments can be seen and are called Zone 1, Zone 2, and Zone 3, corresponding to the first, second, and third-stage planetary gear set, respectively. Oil splashing behavior resulting from planetary gear rotation can be observed through a transparent window mounted on the top cover.

Figure 4 indicates that the oil volume in the second and third planetary stages is greater than in the first stage due to their rotational motion.

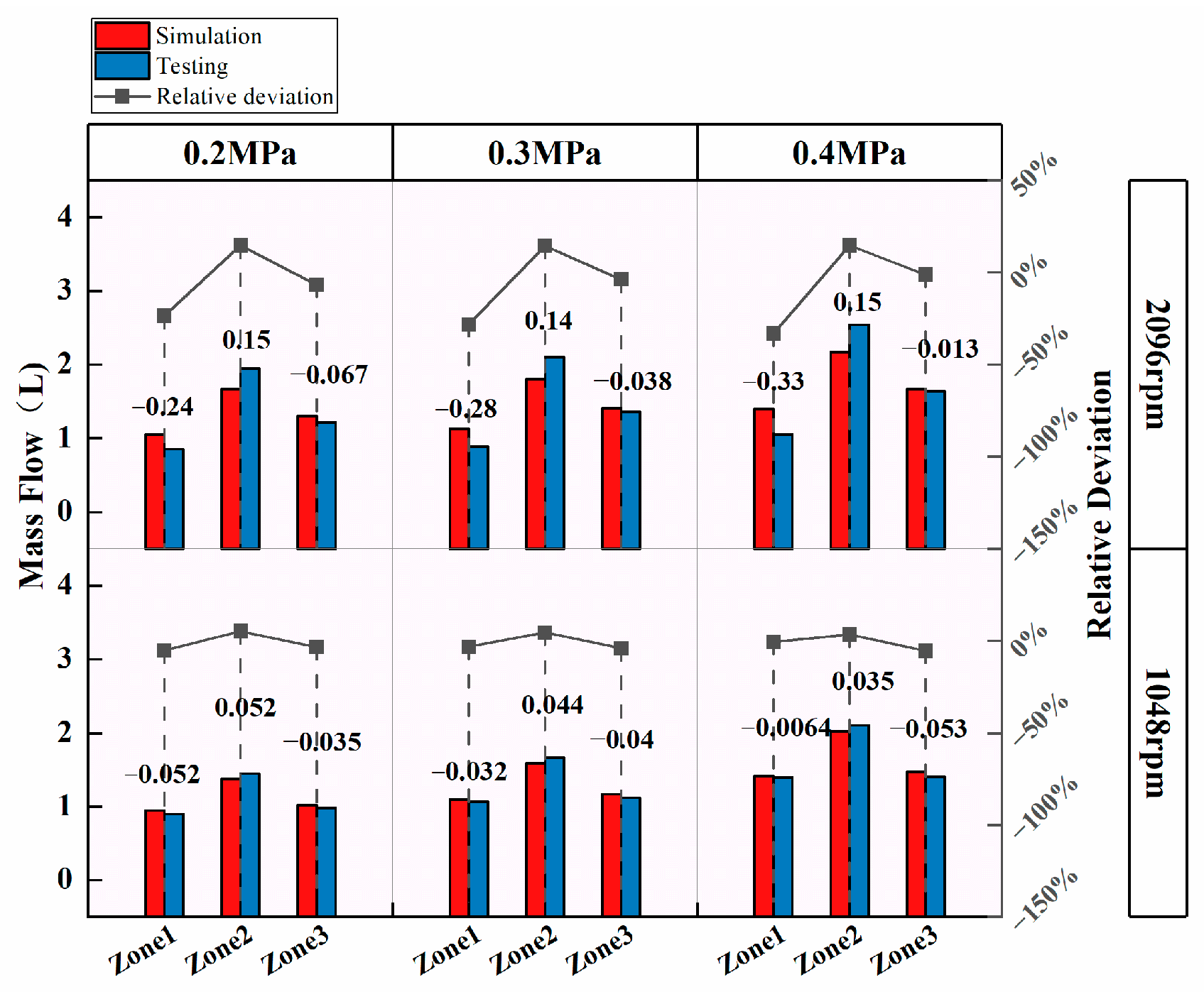

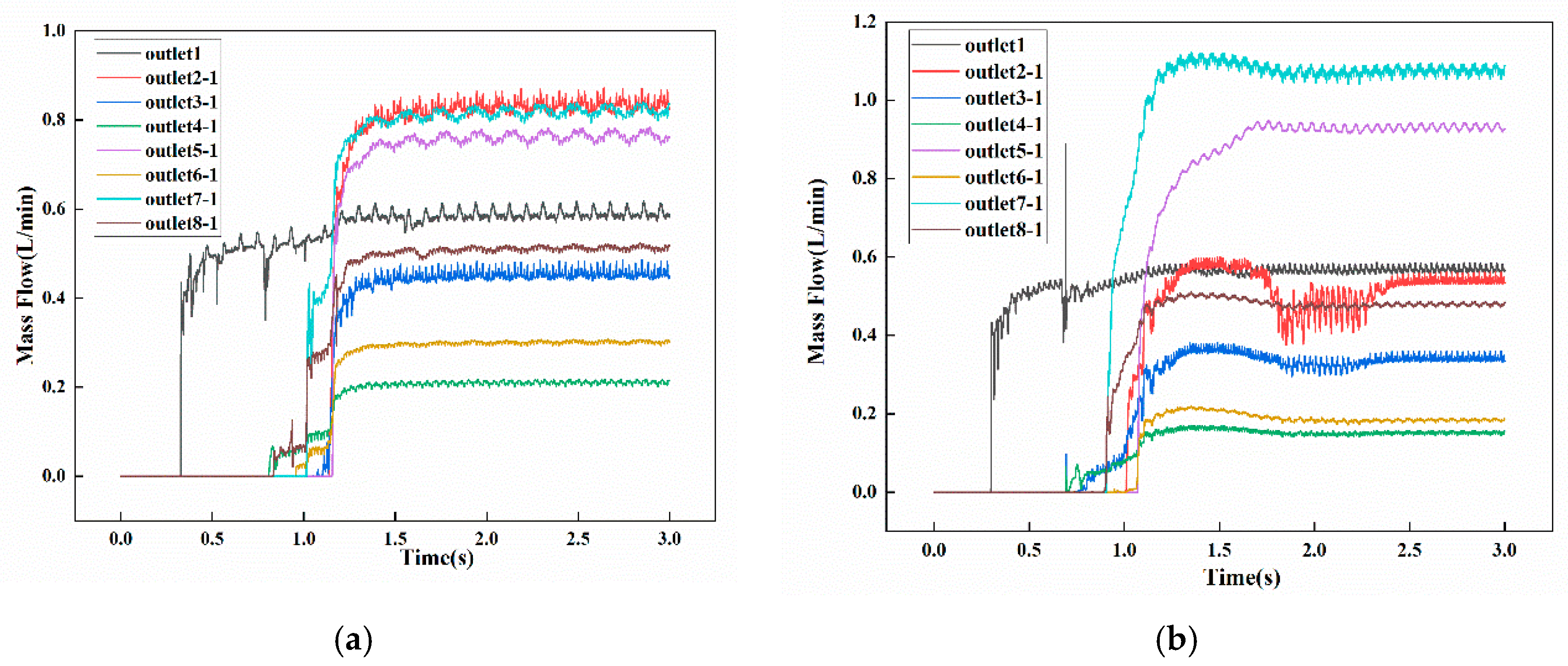

The proposed numerical methods are validated by comparing the simulated oil discharge volumes from each planetary stage with the corresponding experimental measurements. The experiments are conducted under inlet oil pressures of 0.2 MPa, 0.3 MPa, and 0.4 MPa at drive speeds of 1048 rpm and 2096 rpm. The relative deviations of oil volumes between experimental and simulated results are calculated, as illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. As shown in the figures, the simulation results are in good agreement with the experimental data. At 1048 rpm, the maximum observed deviation is 5.3%. At 2096 rpm, larger deviations are observed in Zone 1 and Zone 2, with maximum errors of 33.2% and 14.7%, respectively, and Zone 3 shows a maximum error of 6.8%. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased centrifugal force resulting from the higher rotational speed and oil pressure, which enhances the oil discharge in Zone 2 and reduces the outflow in Zone 1. Despite these discrepancies, the relative errors remain within an acceptable range for engineering applications; therefore, the proposed numerical methods can be considered suitable for analyzing the lubrication behavior of multi-stage planetary transmission systems under a wide range of operating conditions.