1. Introduction

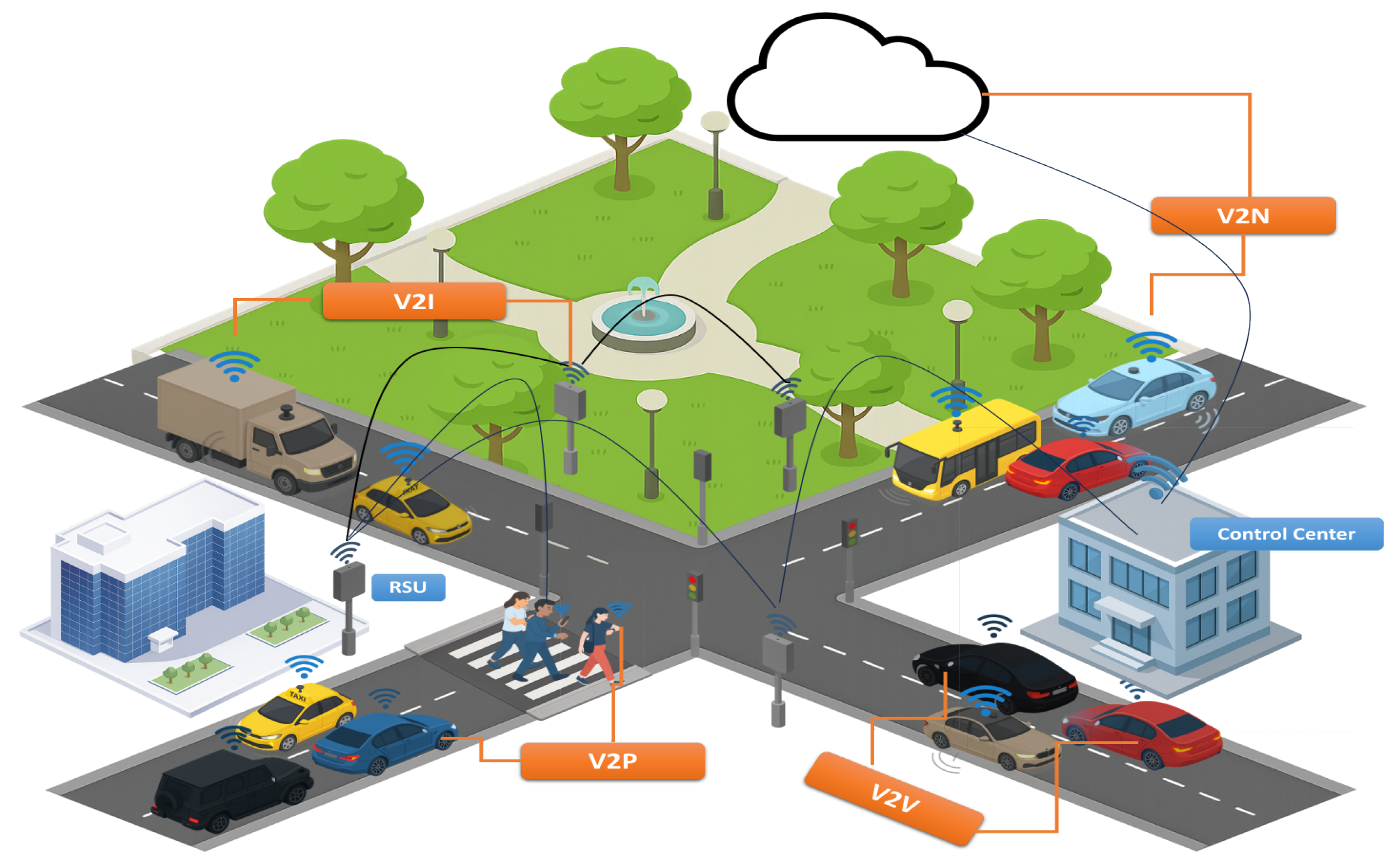

The rapid evolution of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) technology has become a cornerstone of modern smart city (SC) development, contributing significantly to safer roads, improved traffic coordination, and more efficient urban mobility [

1,

2]. In these environments, connected vehicles maintain continuous communication with roadside units (RSUs), vehicular cloud infrastructures, and centralized traffic systems, enabling real-time decision-making for tasks such as autonomous navigation, dynamic rerouting, and collision avoidance [

3,

4] (see

Figure 1). This constant data exchange fosters decentralized intelligence, allowing transportation networks to adapt dynamically to shifting urban conditions [

5,

6]. Importantly, this ecosystem spans heterogeneous computational environments. Resource-constrained on-board units (OBUs) must collaborate with more powerful RSUs and cloud infrastructures, creating a multilayered processing landscape. At the city scale, scalable big-data stacks (e.g., Hadoop/Spark) enable high-throughput processing of diverse vehicular data and have proven effective for intelligent traffic monitoring [

7,

8,

9].

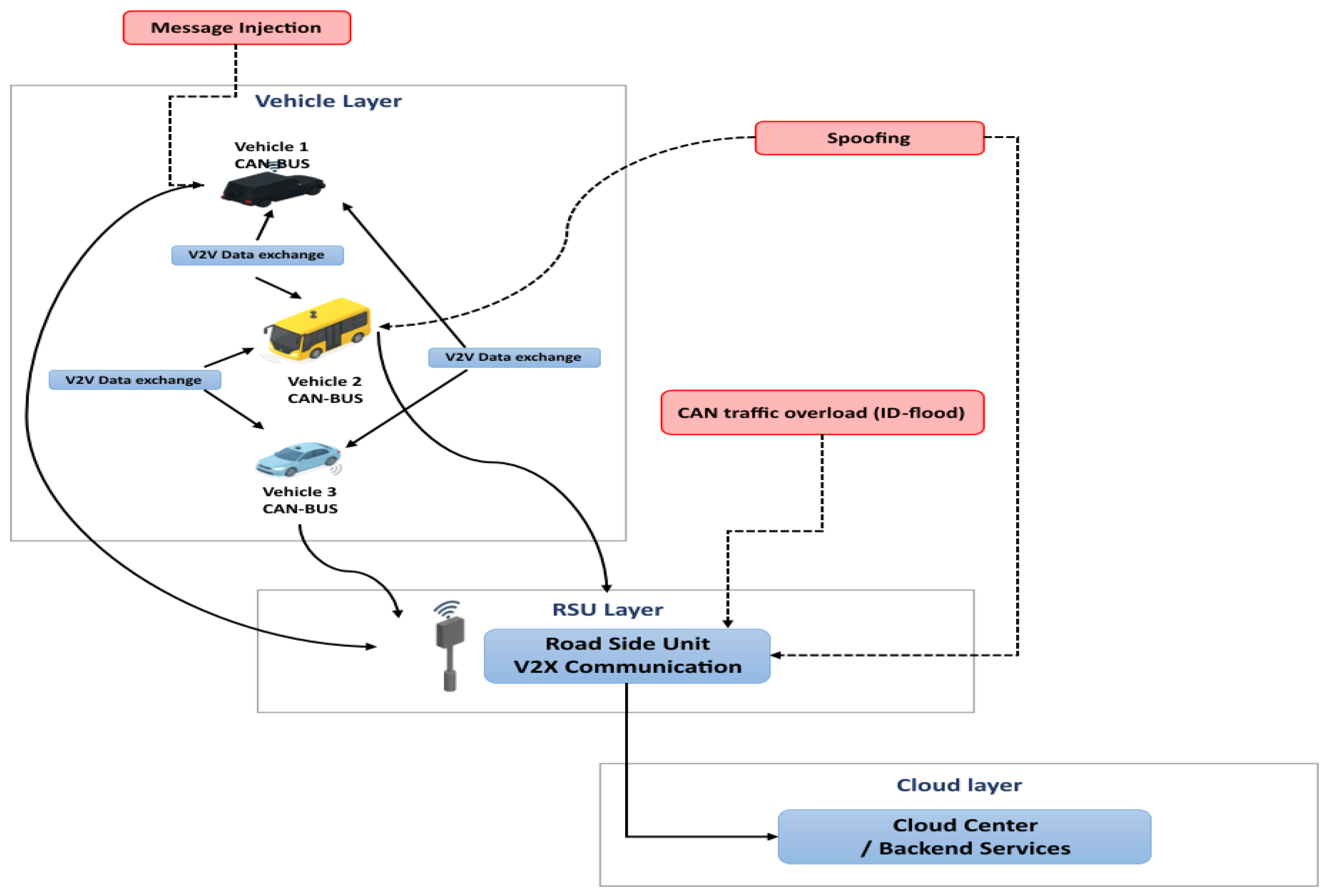

While SC-IoV deployments enable real-time coordination and safety improvements, they introduce a new cybersecurity environment that differs from traditional IT systems in terms of attack surface, operational impact, and system constraints. Unlike static networks, IoV entails vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-cloud (V2C) exchanges that create distinct attack entry points spanning from CAN bus and V2X radios to RSUs and cloud backends [

10]. These heterogeneous links broaden the system’s exposure to malicious interference and complicate defensive design. The layered architecture in

Figure 2 illustrates representative attack vectors across IoV layers—message injection, spoofing, and traffic overload. These attacks can compromise data integrity, endanger physical safety, and disrupt urban traffic flow.

IoV environments face a broad range of cyber threats, but two categories are especially critical for safety and reliability: (1) availability, which is threatened by high-rate traffic overload attacks that delay or block safety messages, and (2) integrity/authenticity, compromised by the spoofing of plausible signals such as GAS, RPM, or SPEED. These two pillars form the foundation of the proposed defense framework, as both directly affect the timeliness and trustworthiness of vehicular communication. Rule-based approaches cannot adapt to such dynamic, stealthy intrusions, whereas machine learning (ML) models can capture temporal dependencies and evolving traffic behaviors, enabling accurate real-time discrimination under varying conditions. For this initial implementation, we narrow the scope to traffic overload and spoofing attacks using CICIoV2024. This controlled focus allows us to validate the hierarchical IDPS under realistic but manageable conditions before expanding to broader threat categories.

Our dataset does not include vehicle-to-everything (V2X)/basic safety messages (BSM) exchanges; in this work we restrict evaluation to CICIoV2024 (in-vehicle controller area network bus [CAN bus] traffic) to ensure methodological alignment with IoV/CAN-specific threats.

Moreover, the operation of IoV systems faces strict resource and timing limitations. While modern high-end vehicles integrate powerful domain controllers supporting advanced driver-assistance systems, many in-vehicle nodes—particularly in low-cost or legacy models—still rely on microcontroller-based electronic control units (ECUs) with limited memory and compute resources [

11]. This creates stark disparities in on-vehicle processing capacity, and security mechanisms must be tailored accordingly. The time-sensitive nature of critical intersections demands millisecond-level decision-making, as any delay in intrusion detection could trigger cascading effects such as traffic congestion or accidents. Furthermore, the combination of vehicle mobility, fluctuating connectivity, and manufacturer-specific communication protocols complicate the design of adaptable and generalized detection models [

12]. Together, these constraints highlight the need for a multilayered defense strategy capable of rapid local decisions and deeper upstream analysis.

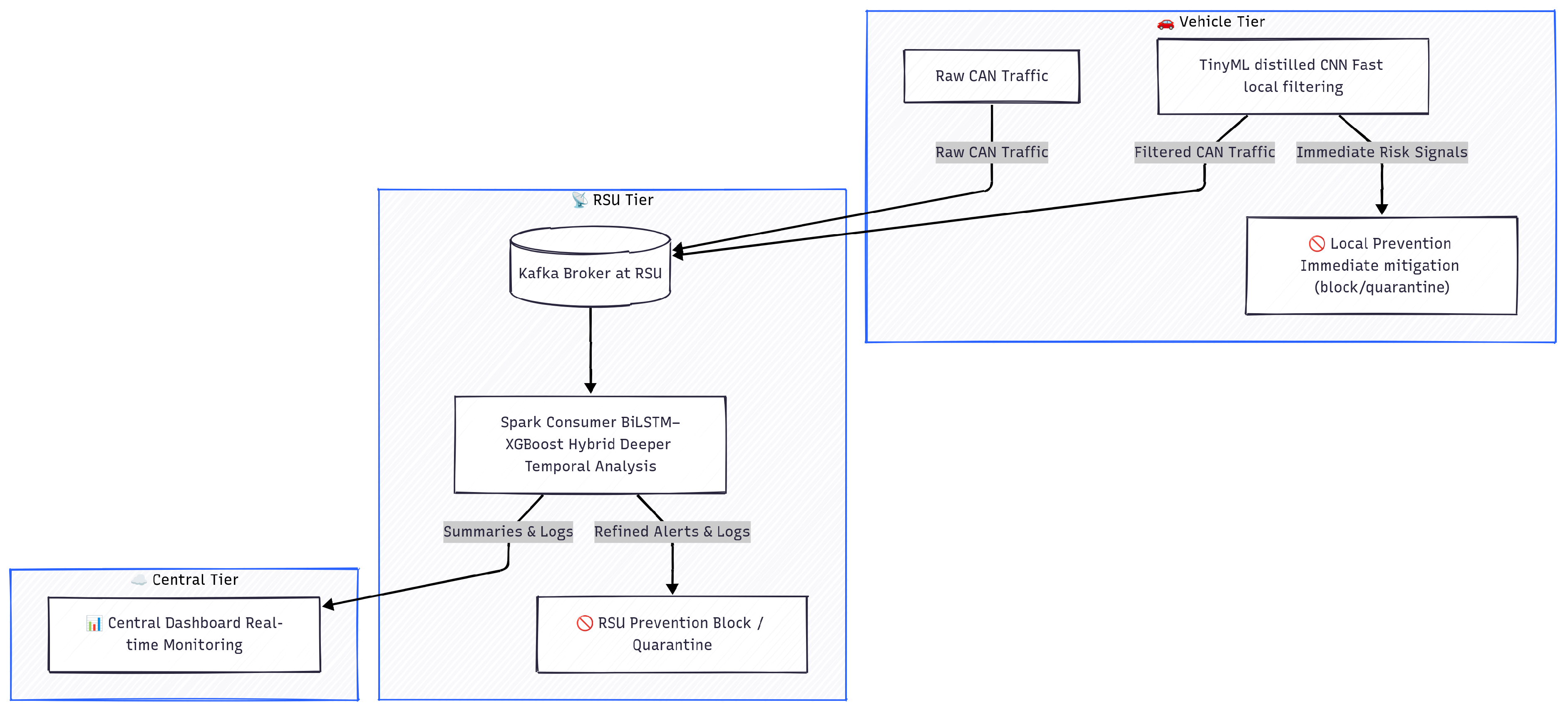

These challenges (tight real-time budgets, safety stakes, and resource constraints) require a new breed of lightweight, understandable, and high-speed Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDPS). Recent hybrid detection models combining deep learning (DL) and gradient boosting have shown promising results for securing vehicular environments [

13]. Building on this insight, our framework adopts a hierarchical defense strategy: a TinyML-based distilled CNN on vehicles for ultra-fast on-device detection, a BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid model at RSUs for deeper temporal–spatial analysis of traffic flows, and a centralized Kafka–Spark Streaming layer for city-wide monitoring, coordination, and adaptive model updates [

14,

15]. This tiered design balances immediacy, depth of analysis, and operational scalability under realistic smart intersection conditions.

Many existing IDPSs suffer from critical limitations, despite various efforts to secure IoV environments. Traditional rule-based approaches fail to adapt to new attack methods, while standalone DL models, despite their high accuracy, require excessive computational resources, which make them unsuitable for SC environments with time-sensitive requirements [

16]. Moreover, the fast operation of lightweight models, including decision trees and SVMs, does not allow them to detect sequential patterns in vehicular communication streams [

17]. These limitations underline the necessity for hybrid approaches that combine temporal modeling with efficient decision mechanisms.

To address these limitations, we propose a multi-stage hybrid IDPS that leverages (i) the temporal modeling strengths of Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks, (ii) the decision efficiency of XGBoost, and (iii) vehicle-level TinyML CNN students for ultra-lightweight detection. We begin by conducting offline benchmarking on the vehicular CAN bus dataset CICIoV2024, comparing several DL architectures including CNN, BiLSTM, LSTM, GRU, and FastKan. Based on detection accuracy and runtime metrics, BiLSTM was selected as the optimal temporal encoder. The final BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid is deployed in a Kafka–Spark Streaming pipeline, enabling real-time classification of windowed CAN bus traffic simulated using CICIoV2024. At the same time, the TinyML CNN student, which was distilled from the hybrid BiLSTM-XGBoost model, provides a first layer of rapid filtering directly on vehicles, ensuring minimal latency for obvious threats.

Our approach builds on recent findings that hybrid DL-tree ensemble models can outperform monolithic networks in high-throughput edge security tasks [

18]. Before real-time deployment, multiple deep and hybrid architectures were evaluated on CICIoV2024 to guide the selection of the BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid model for its balance between accuracy and latency. The core contributions of this study are summarized below.

A hierarchical, multi-stage IDPS that combines a TinyML-distilled CNN on vehicles for ultra-lightweight detection with a BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid at RSUs for deeper temporal–spatial analysis.

(Architecture and roles are detailed in

Section 4; end-to-end (e2e) evaluation is in

Section 7).

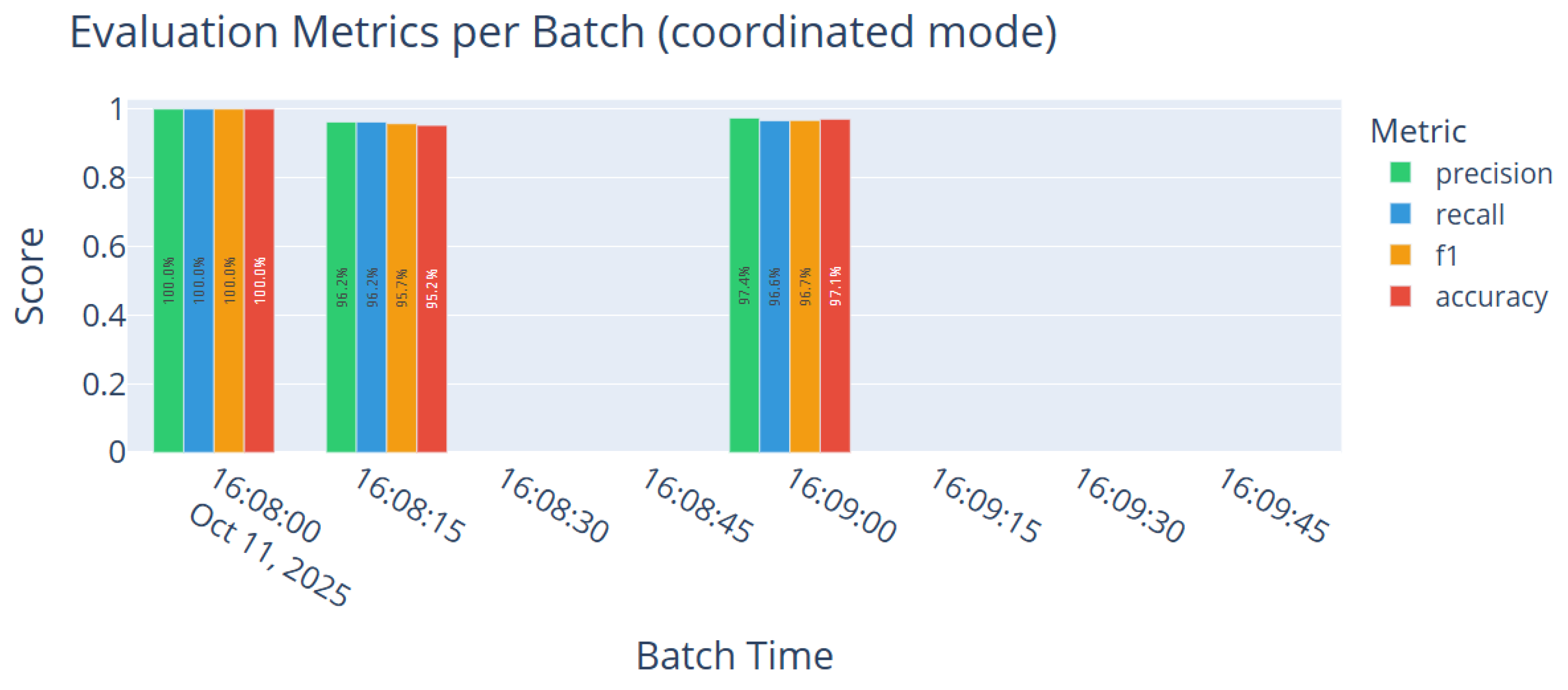

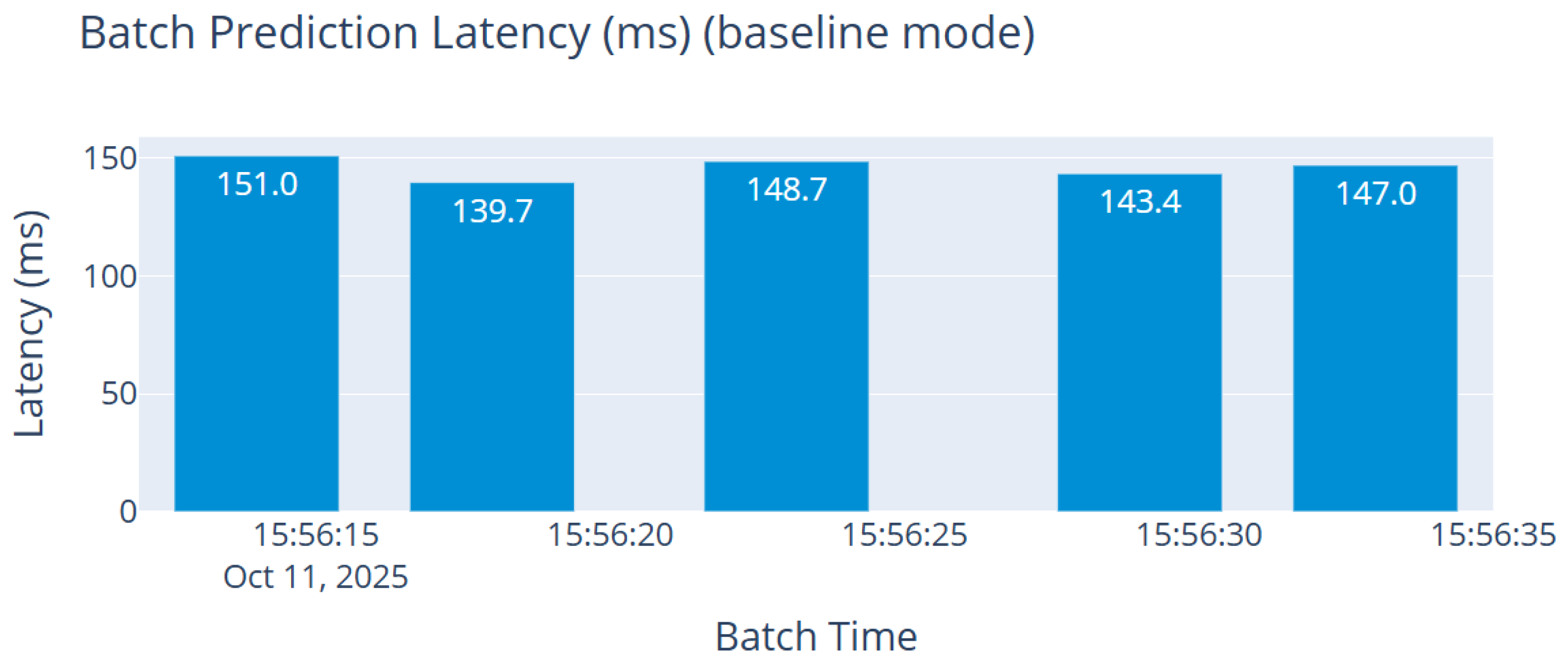

Real-time deployment within a Kafka–Spark Streaming pipeline, enabling scalable, low-latency classification and automated prevention actions at SC intersections.

(Streaming and actions described in

Section 6.2; policy parameters detailed later in

Section 6.2.2; average batch latency ≈ 153 ms with resilience under bursts in

Section 7).

A practical real-time dashboard integrated into the proposed Kafka–Spark IDPS pipeline, used to monitor detection outcomes, prevention actions, and system health, thereby supporting operator situational awareness in IoV environments.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the proposed hierarchical multi-stage IDPS architecture.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on intrusion detection in IoV.

Section 3 discusses security challenges at SC intersections and the motivation for a hierarchical defense.

Section 4 presents the system architecture and threat model, including the roles of the vehicle, RSU, and central tiers.

Section 5 describes the offline development and evaluation of various models.

Section 6 details the real-time implementation of the full system using Kafka–Spark, covering both TinyML deployment at the vehicle level and hybrid model integration at the RSU.

Section 7 reports the experimental results across the two levels and different operational modes, including performance metrics and latency for both TinyML and hybrid components.

Section 8 discusses the system’s limitations, open issues, and possible directions for future research. Finally,

Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

The IoV continues to face growing cybersecurity threats, particularly through vulnerabilities in the CAN bus and V2I communication layers. Numerous studies have explored ML and DL approaches to enhance the effectiveness of IDPS. While these efforts have improved detection accuracy, many solutions remain limited to offline experimentation, and deployment-ready real-time integration is still uncommon.

The authors of [

19] proposed one of the few truly real-time IDS solutions using a Kappa Architecture. Their system combines Spark Streaming with ensemble learning models—Random Forest, XGBoost, and Decision Trees—to detect CAN bus attacks such as DoS, spoofing, fuzzing, and replay. Achieving up to 98.5% accuracy and low-latency detection (as fast as 0.26 s), the work demonstrates solid real-time processing capabilities. However, the system lacks attack prevention and operational monitoring, and its traffic simulation capabilities are restricted, which our framework addresses.

Similarly focused on real-time detection, ref. [

20] introduced HistCAN, a self-supervised lightweight IDS for in-vehicle networks. HistCAN uses a hybrid encoder with historical information fusion to learn from benign CAN traffic and detect anomalies via reconstruction errors. With F1-scores up to 0.9954 and throughput near 8900 frames per second on GPU, the system is well suited for embedded deployment. Despite this efficiency, it does not incorporate data streaming, prevention logic, or live operator feedback—capabilities that our Kafka–Spark pipeline and dashboard explicitly provide.

Offline-focused studies have also advanced IoV IDS models. Ref. [

21] evaluated a broad set of traditional ML models on CICIoV2024, without balancing, thus preserving real traffic priors. Using Optuna for hyperparameter tuning, XGBoost and other ensembles achieved near-perfect accuracy. Nevertheless, the study remains confined to static offline evaluation and does not include real-time processing or mitigation strategies.

Expanding on architectural design, Uddin et al. [

22] proposed a scalable hierarchical IDS for IoV, organizing detection into layered classifiers with Boruta-based feature selection. Although conceptually promising for edge–cloud collaboration, the work is neither implemented in real-time nor equipped with streaming, prevention, or monitoring functionalities.

Several DL ensemble approaches focus on accuracy via multi-perspective feature extraction. El-Gayar et al. [

23] proposed DAGSNet, combining DenseNet, AlexNet, GoogleNet, and SqueezeNet with wavelets and attention for feature fusion. While achieving high offline accuracy, the approach is computationally heavy, non-adaptive, and not suited to CAN bus or real-time constraints.

Ref. [

24] introduced DFSENet, using lightweight ensembles to achieve fast classification with reported inference times of 12 ms. However, the model is evaluated only offline and lacks integration with real-time alerts or traffic simulation, which limits its operational readiness.

In the context of hybrid DL, Kamal and Mashaly [

25] proposed a CNN-MLP model enhanced by ADASYN and SMOTE to balance IoT data. Despite strong binary and multi-class results, the study is generic to IoT, lacks CAN bus specificity, and provides neither real-time streaming nor attack response logic.

Ref. [

26] evaluated multiple DL architectures—including BiLSTM, GRU, and CNN—across three CAN datasets. The models achieved near-perfect static performance, confirming the value of temporal learning. However, their setup does not incorporate real-time adaptability, prevention actions, or system-level observability.

With the rise of edge-ready security, ref. [

27] proposed a TinyML-based IDS for ultra-constrained devices (e.g., Arduino UNO), exploring ensembles (Random Forest, Extra Trees, and XGBoost) for low-latency inference under tight memory/compute budgets. While demonstrating the feasibility of distributed edge detection, the study omits attack response, live streaming or simulation, and operator-oriented feedback mechanisms.

Meanwhile, ref. [

28] introduced a TinyML-based IDS targeting generic IoT environments. A lightweight CNN was deployed with TensorFlow Lite for microcontrollers using quantization and pruning for efficiency. Despite strong results on NSL-KDD and BoT-IoT, the approach targets generic network traffic rather than CAN bus and lacks domain-specific optimizations such as spoofing characteristics, temporal dependencies, or coordinated-attack scenarios. It also does not include streaming, prevention mechanisms, or real-time monitoring.

In a closely related study, ref. [

29] developed a TinyML-based IDS for CAN bus using a compact CNN on an nRF52840 microcontroller. A dual-branch design processes CAN ID sequences and payloads, enabling accurate detection of spoofing and fuzzing under strict resource limits. Although this validates true TinyML deployment for local anomaly detection, the approach remains detection-only and does not integrate simulation frameworks, real-time streaming, or attack response logic.

In contrast to these works, our study delivers a deployment-ready, real-time IDPS built on a Kafka–Spark Streaming backbone. It combines deep temporal encoding (BiLSTM) with fast, accurate classification (XGBoost) at the RSU tier, plus a TinyML-distilled CNN for ultra-lightweight on-vehicle detection. Beyond detection, it supports dynamic attack simulation (baseline, stealth, and coordinated), automated prevention (blocking and quarantine), and operator-facing monitoring for continuous situational awareness, closing the gap between academic prototypes and operational IoV security.

More specifically, the proposed H-RT-IDPS introduces several capabilities not jointly provided by prior IoV or edge–cloud IDS frameworks. First, we deploy a TinyML CNN student directly on the vehicle, enabling on-board detection under strict OBU memory and latency constraints—an aspect missing in existing real-time IoV IDS research. Second, we apply a teacher–student knowledge-distillation pipeline that transfers calibrated decision boundaries from a BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid at the RSU tier to the TinyML model, whereas prior work does not leverage cross-tier learning. Third, our system integrates Kafka–Spark for real-time streaming, attack simulation, automated prevention (blocking/quarantine), and dashboard-based operator monitoring, going beyond detection-only designs. Finally, unlike studies that treat spoofing as a single generic class, we provide fine-grained subclass detection (GAS, RPM, SPEED, and STEERING) alongside traffic overload, strengthening practical applicability to safety-critical IoV environments.

Beyond IoV-specific work, recent efforts in broader IoT and cloud security have explored complementary ideas such as time-aware deep learning and hierarchical fog-based defense architectures. For example, time-aware IDS models [

30] integrate temporal sensitivity into intrusion detection for cloud and IoT infrastructures, while fog-based hierarchical security frameworks [

31] distribute monitoring and analysis between edge, fog, and cloud layers. These frameworks share conceptual similarities with our multi-tier design, particularly the emphasis on time-sensitive detection and tiered processing. However, they do not address CAN bus semantics, fine-grained spoofing subclasses, or on-vehicle TinyML deployment, which are central to the proposed H-RT-IDPS.

For a consolidated view,

Table 1 summarizes datasets, model families, and operational readiness (real-time, prevention, monitoring, TinyML, and simulation) across recent IoV IDS works.

3. Smart City Intersection Security

Building on the limitations observed in prior work, this section examines security implications of deploying IDPS at smart-city (SC) intersections—one of the most vulnerable and critical environments in the IoV ecosystem.

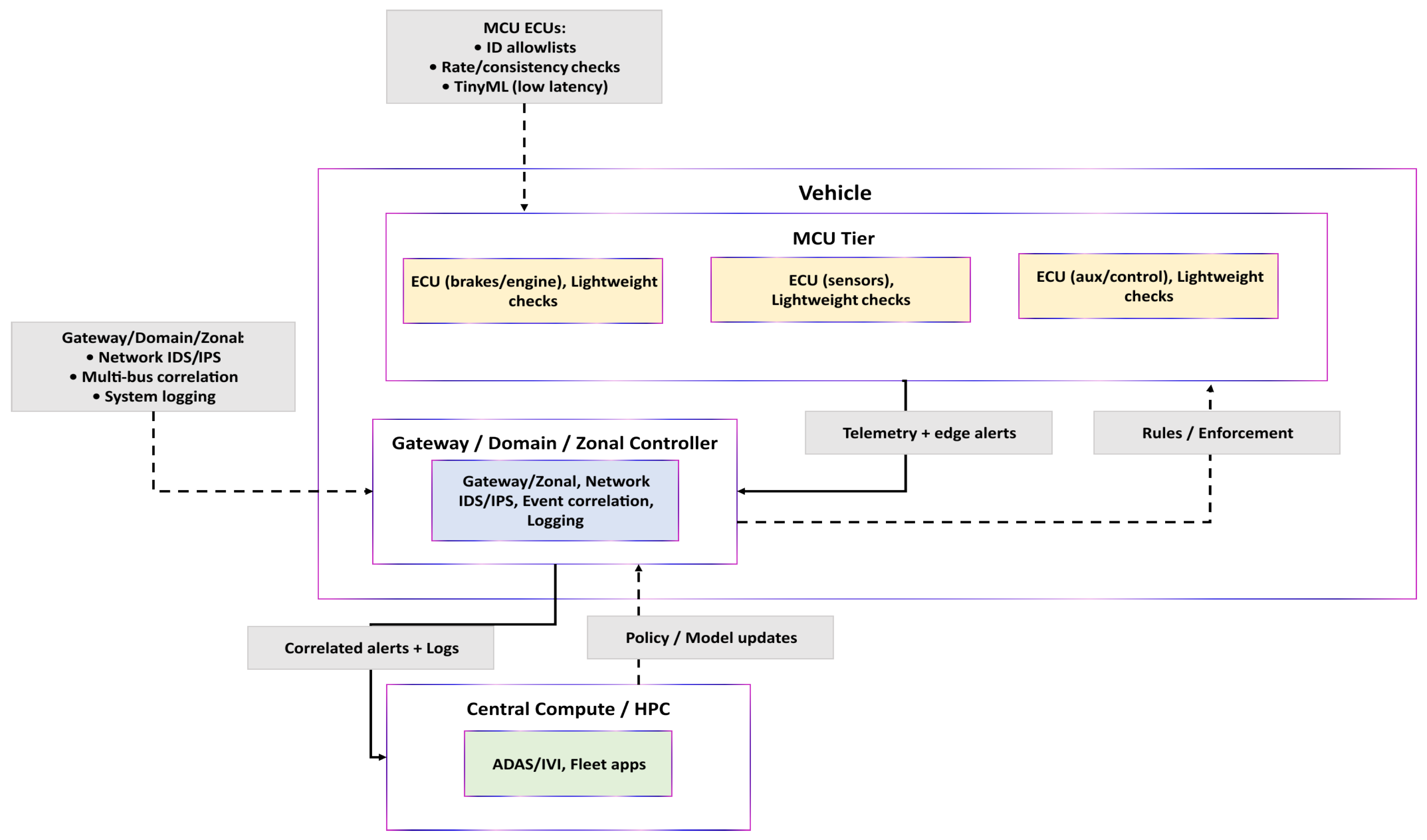

3.1. Background: In-Vehicle Architectures and IDS Placement

Vehicle electronics are transitioning from many domain-specific units to zonal layouts, where a small number of higher-capacity controllers supervise groups of ECUs [

32]. We distinguish three roles:

MCU-based ECUs(e.g., Arm Cortex-M): Small, low-power controllers for time-critical functions under tight memory/CPU budgets; suitable for lightweight screening (ID allowlists, basic rate/consistency checks, and TinyML).

Gateway/Domain/Zonal controllers (often Cortex-A or automotive SoCs): Aggregate CAN/CAN-FD and Automotive Ethernet; host shared services and network IDS with cross-bus correlation and logging.

Central compute/HPC: Platforms for compute-intensive functions (e.g., ADAS and IVI) and fleet-scale analytics.

In deployed systems, heavier intrusion-detection tasks reside on gateway/zonal controllers due to network visibility and compute headroom [

32,

33]. MCU ECUs provide first-line, low-latency screening and can run TinyML-scale anomaly filters when millisecond response is required [

34]. Alerts/summaries are forwarded to the gateway for system-level correlation and action.

Placement in our framework. The vehicle tier performs TinyML screening on resource-limited ECUs; the RSU tier executes the hybrid analysis (BiLSTM feature extractor →

XGBoost classifier) for real-time decisions; and the cloud tier correlates alerts across intersections and manages policy/model updates.

Figure 4 summarizes the tiers and IDS placement.

A hierarchical architecture introduces potential blind spots at the boundary between the vehicle’s TinyML screening and the RSU’s temporal analysis. Because the OBU performs lightweight anomaly filtering, an attack that is too subtle for the TinyML CNN student yet insufficiently persistent may not trigger an explicit alert. To mitigate this, the vehicle tier periodically forwards compact summaries of recent CAN bus activity to the RSU, ensuring that the RSU always receives minimal contextual information even when no alert is raised. Synchronization across heterogeneous sampling rates is handled at the RSU: all received packets are re-timestamped upon arrival, and sliding-window formation for BiLSTM–XGBoost inference is carried out on a unified RSU-controlled timeline. Late or jittered packets are buffered within a tolerance bound before window assembly, thus preventing temporal drift between vehicles with different sensing, processing, or transmission latencies. This design minimizes misalignment and reduces blind-spot exposure at the hierarchical handoff.

3.2. Smart City Intersection Scenario and IoV Communication Flows

SC intersections are among the busiest points in urban transportation networks, where vehicles, roadside infrastructure, pedestrians, and cloud platforms interact in real-time. Each connected vehicle carries an on-board unit (OBU) that continuously shares telemetry (e.g., position, speed, and braking status), while RSUs at intersections aggregate this data, interface with traffic-light controllers, and relay information to centralized platforms. Pedestrian detectors and cameras complement this setup, forming a multi-tier IoV network across V2V, V2I, and V2C communication layers [

35].

Communication at intersections typically occurs at three levels:

V2V. Vehicles approaching the same intersection exchange basic information (speed and braking status). This enables earlier responses by revealing vehicles occluded by trucks or buildings. Vehicles near stopped cars at crosswalks receive immediate alerts, reducing crash risk.

V2I. This layer coordinates vehicles, traffic lights, and RSUs. Emergency vehicles can request preemption (temporary green waves) and broadcast warnings to surrounding drivers. Daily drivers receive advance warnings about red lights, pedestrian crossings, and sudden road closures.

V2C. Operating at a city-wide level, RSUs transmit data to the cloud, where it is fused across intersections. Traffic management systems then identify emerging congestion and adjust signal timing or reroute before problems escalate.

These three layers operate jointly to enhance overall performance: V2V supports rapid, safety-critical reactions; V2I manages local vehicle-infrastructure coordination; and V2C maintains city-level synchronization, helping intersections remain smooth under both routine and unexpected conditions [

36].

Consequently, securing SC intersections benefits from a hierarchical, layered approach: lightweight detection on vehicles filters obvious threats at the edge; RSUs perform deeper temporal analysis and enforcement; and the cloud coordinates city-wide responses to maintain resilience [

37,

38].

3.3. Security Risks and the Need for Millisecond-Level Detection at Intersections

Attackers target intersections because small disruptions can have outsized consequences. False-signal injection may induce conflicting greens and crashes; fake emergency alerts can hijack traffic flow; and RSU-level traffic overload can disrupt vital V2I communications, preventing timely pedestrian/hazard warnings. Even brief interruptions can cascade into congestion, secondary collisions, and city-wide gridlock [

39].

The urgency of intersection decisions amplifies these risks. Emergency braking and ambulance right-of-way decisions must occur within milliseconds; any detection or response delay leaves no recovery margin and directly affects safety.

Recent work reinforces the importance of resilient cyber–physical coordination in SC infrastructures. Authors in [

40] highlight how integrating advanced computation models such as quantum computing with digital-twin technologies can strengthen the resilience of transportation and power systems against false-data injection attacks, one of the most critical threats facing modern Cyber–Physical Systems (CPS). Similarly, authors in [

41] examine system-level remedial strategies for mitigating FDI attack impacts, emphasizing the need for coordinated, multi-layer defensive mechanisms in safety-critical infrastructures. These insights support the requirement for multi-tier, low-latency intrusion detection at urban intersections, aligning with the design principles of our H-RT-IDPS framework.

To address these risks, we adopt a multilayered defense:

Vehicle tier (TinyML). The system performs first-line filtering against spoofed or inconsistent messages using lightweight on-device models.

RSU tier (temporal hybrid). The BiLSTM-XGBoost analysis is utilized to analyze sophisticated or coordinated patterns at the intersection scale.

Cloud tier (correlation). Aggregation across intersections to detect large-scale threats via alert correlation and global policies [

6].

Table 2 summarizes the main communication types at intersections, their normal functions, potential attack vectors, and how the proposed multi-tier IDPS mitigates these threats.

3.4. Justification for a Hierarchical Defense Strategy

Securing SC intersections is best achieved with a defense-in-depth architecture that assigns each security function to the tier whose compute and latency budgets fit the task. Vehicles operate under stringent memory/CPU limits and must react within milliseconds; RSUs can sustain richer temporal analytics at the intersection scale; the cloud aggregates multi-intersection signals for city-wide situational awareness but cannot provide immediate, per-packet intervention.

Vehicle tier (on-board TinyML).

On-board units (OBUs) run lightweight models that provide the first line of defense by filtering obvious anomalies in situ (e.g., spoofed speed/braking signals or location claims). By suppressing malicious traffic before it propagates, on-vehicle filtering reduces unsafe actuation risk and lowers downstream load-critical under intersection-level deadlines. Events that exceed this tier’s capacity or show non-local patterns are forwarded to the RSU for deeper analysis.

RSU tier (intersection-scale temporal analytics).

Roadside units collect streams from multiple vehicles and analyze patterns over time. Leveraging the BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid, this tier targets coordinated or timing-sensitive threats (e.g., spoofing combined with traffic overload bursts or infrastructure impersonation) while meeting the operational latency bounds required for live signal control. With greater processing headroom than vehicles, RSUs perform deeper spatio-temporal inference and enforce prevention at the intersection boundary. Summaries and alerts are then promoted to the cloud when cross-site correlation or longer-horizon analysis is needed.

Cloud tier (city-wide correlation and adaptation).

The cloud correlates alerts across RSUs to surface large-scale behaviors that may be invisible locally (e.g., district-level congestion spoofing), supports the model lifecycle (updates, calibration, and drift handling), and provides operator-facing situational awareness. Rather than acting as a real-time control point, it refines policy and improves lower-tier models using historical and cross-site evidence. Updated policies/models are then propagated back to RSUs and vehicles.

In combination, the three tiers deliver immediate edge responses, deeper intersection scale assessment, and city-wide coordination. This layered structure also yields graceful degradation: if one tier is impaired, the others continue to provide protection appropriate to their scope, preserving safety and continuity of operations at SC intersections.

5. Offline Model Development and Benchmarking

5.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

We used the CICIoV2024 [

43] public dataset, which contains in-vehicle CAN bus traffic (benign plus traffic overload/spoofing) and is used to model vehicle-tier threats and to construct temporal windows for TinyML/BiLSTM.

CICIoV2024 Dataset

The CICIoV2024 dataset is a modern in-vehicle CAN bus benchmark for intrusion detection, containing authentic CAN traffic under normal driving and attack conditions. Each message record includes a CAN identifier (ID), eight data bytes (DATA_0-DATA_7), and three labeling fields: label (benign/malicious), category (attack family), and specific_class (exact attack type). Following methodological guidance [

42], we exclude non-vehicular corpora to avoid misaligned features and focus strictly on CAN bus IoV threats.

Table 5 summarizes the attack composition and class distribution of CICIoV2024. The dataset comprises approximately 1.4 million CAN frames, covering both benign traffic and multiple high-impact CAN bus attacks.

This imbalance reflects real-world conditions, where malicious events are rare compared to normal traffic, requiring the use of class weights during training.

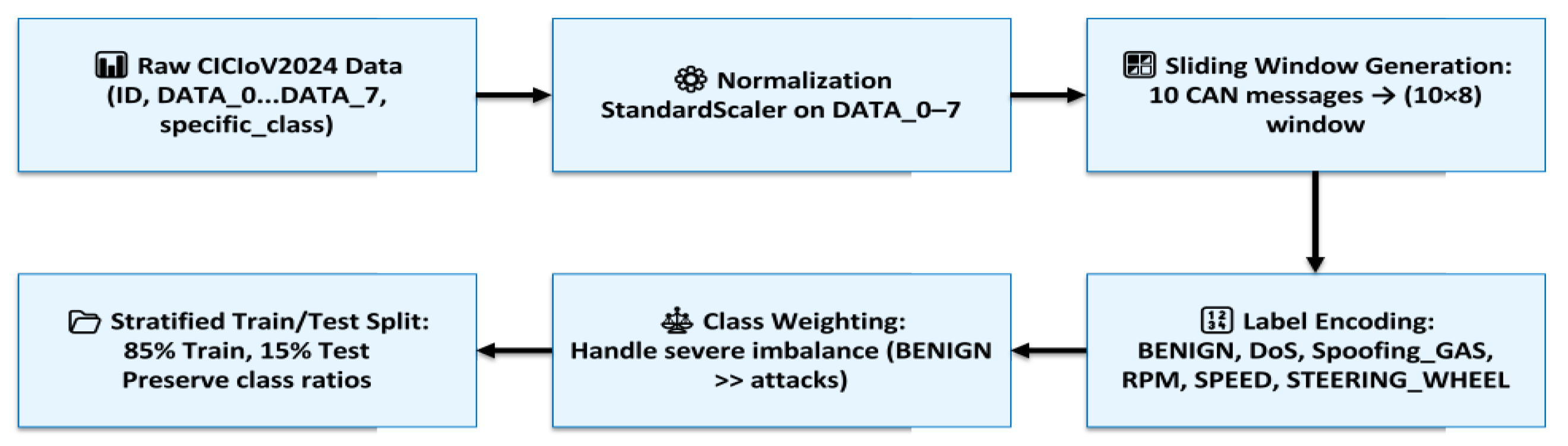

Preprocessing steps. To exploit the temporal nature of CAN traffic, we applied a sliding-window strategy:

Normalization: All DATA_0 to DATA_7 byte values were scaled with a StandardScaler to zero mean and unit variance:

Sliding-window generation: Consecutive CAN frames were grouped into 10-message windows, producing input tensors of shape . The label of each window was determined by the majority attack type within the window.

Label encoding: Categorical labels (BENIGN, DoS, and spoofing types) were mapped to integer classes for model compatibility.

Class balancing: Computed class weights mitigated the effect of minority attack categories.

Train/test split: A stratified 85/15 split ensured proportional representation of all attack types in both training and test sets.

To avoid any form of data leakage, we explicitly clarify our partitioning strategy. The train–test split is performed randomly at the frame level after shuffling the full CICIoV2024 dataset. No scenario-based or session-based partitioning is used. CICIoV2024 does not organize attacks into long campaign sessions; instead, attacks appear as short, independent CAN bus message windows. As a result, shuffling followed by random frame-level splitting does not allow any coherent attack campaign, temporal trace, or contiguous sequence of injected messages to appear in both training and testing sets. This prevents leakage of attack patterns and ensures that the reported accuracy, precision, and recall reflect a physically plausible evaluation setting for CAN bus intrusion detection.

The resulting preprocessed dataset produces the following:

Using Equation (

4) with

= 1,408,219,

, and

, we obtain

N = 1,408,210 is the total number of sliding windows produced (via Equation (

4)).

Each window spans 10 consecutive CAN frames; each frame has 8 normalized data bytes (DATA_0–DATA_7).

encodes window labels: , , , , , .

The preprocessing pipeline for CICIoV2024 is summarized in

Figure 6.

This transformation preserves the sequential dynamics of CAN bus signals, making it suitable for temporal models such as BiLSTM and GRU. Also, such preprocessing strategies and dataset refinements have also been emphasized in recent IoV/IoT intrusion-detection research, where handling class imbalance and realistic traffic distributions is critical for reliable evaluation [

44].

5.2. Benchmarking Models

A wide range of DL and hybrid models were evaluated on the two datasets to determine which architecture achieves the best balance between detection accuracy and computational cost. The models analyze different patterns in IoV traffic behavior:

CNN: Effective at detecting spatial patterns in individual CAN frames and flow-based features; limited in capturing long-range temporal patterns.

LSTM: Specializes in sequential analysis and can detect delayed attack signatures via time-based patterns; computationally heavier than CNNs.

GRU: A simpler recurrent alternative to LSTM with fewer parameters, trading some expressivity for speed.

BiLSTM: Extends LSTM with forward and backward processing, which helps identify complex temporal relations and detect stealthy attacks.

FastKAN: Uses kernel activation networks to extract lightweight features while maintaining compactness for high-speed inference.

XGBoost: A decision-tree ensemble that delivers fast classification on tabular features; performs strongly when fed deep features, but does not model temporal dynamics directly.

Hybrid (BiLSTM + XGBoost): BiLSTM provides temporal features, and XGBoost performs classification, yielding high accuracy with low inference latency suitable for RSU-level deployment. Recent studies further corroborate that combining temporal deep feature extractors with efficient classifiers strengthens resilience to network-level threats and timing uncertainties in connected vehicles [

45,

46].

Training setup and hyperparameters:

All models were trained on imbalance-aware version of CICIoV2024 using consistent preprocessing and evaluation procedures. CNN, LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM were implemented in TensorFlow and trained for up to 10 epochs with early stopping (patience = 3, best weights restored), batch size 512, Adam optimizer, and categorical cross-entropy loss, with a validation split of 0.2. FastKAN was trained in PyTorch with a batch size of 1024 and a learning rate of 0.001. XGBoost and hybrid variants used 100 estimators, a learning rate of 0.1, and a maximum depth of 5. Inputs consisted of flattened CAN bus windows of shape

. All experiments were executed on a CPU-only laptop to reflect RSU-level constraints. The configuration in

Table 6 was applied consistently on CICIoV2024 to ensure a fair and reproducible comparison within the CAN domain.

For clarity and reproducibility, we additionally report the full set of XGBoost hyperparameters used in the hybrid model, including tree configuration, sampling ratios, and regularization terms. These settings are summarized in

Table 7.

The full hardware and software specifications of the system used for training are provided in

Table 8.

5.3. Benchmarking Results

All CICIoV2024 results in this section refer to a six-class classifier (BENIGN, DoS, Spoofing_GAS, Spoofing_RPM, Spoofing_SPEED, Spoofing_STEERING_WHEEL), not a binary benign/malicious model. We evaluate each model on CICIoV2024 using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, training time, and prediction latency to balance detection quality and computational efficiency.

Table 9 reports classification (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1) and execution metrics (training, prediction, and total time) on CICIoV2024, providing a comparative view of detection performance and efficiency for real-time IoV deployment.

For standalone DL and XGBoost models, precision/recall/F1 are macro-averaged (equal weight per class). For hybrid DL-XGBoost models, they are weighted-averaged (reflecting class priors in the test set). This provides both per-class fairness and deployment realism.

All models achieve high detection performance (accuracy, precision, and recall/F1 ≥ 98.5%). Recurrent DL models (LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU) deliver competitive accuracy but incur substantially higher training and inference times, which can constrain real-time use. Hybrid models (CNN-XGBoost, LSTM-XGBoost, and BiLSTM-XGBoost) maintain equivalent detection while reducing prediction latency to ∼0.1–0.2 s. Patterns are consistent, indicating that hybrids offer superior time-sensitive performance. Among hybrids, BiLSTM-XGBoost achieves a favorable accuracy-latency trade-off by combining temporal sequence modeling with fast tree-ensemble inference.

As summarized in

Table 9, model complexity strongly influences prediction speed. While CNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU reach high detection scores, they incur higher inference latency than the hybrid variants. In contrast, CNN-XGBoost and BiLSTM-XGBoost preserve accuracy while maintaining sub-second inference consistent with real-time IoV operation. Among them, BiLSTM-XGBoost offers the best balance between temporal representation and low-latency decision-making on CICIoV2024.

Although several temporal–tree hybrids achieved nearly identical offline accuracy on CICIoV2024, the BiLSTM-XGBoost model exhibited the most stable spoofing subclass discrimination with lower variance across folds. The bidirectional encoder generated more consistent latent patterns for RPM-SPEED and GAS-STEERING_WHEEL transitions, while XGBoost provided predictable low-latency inference within the CPU-based Kafka–Spark RSU environment. For these operational reasons, BiLSTM-XGBoost was selected for real-time deployment.

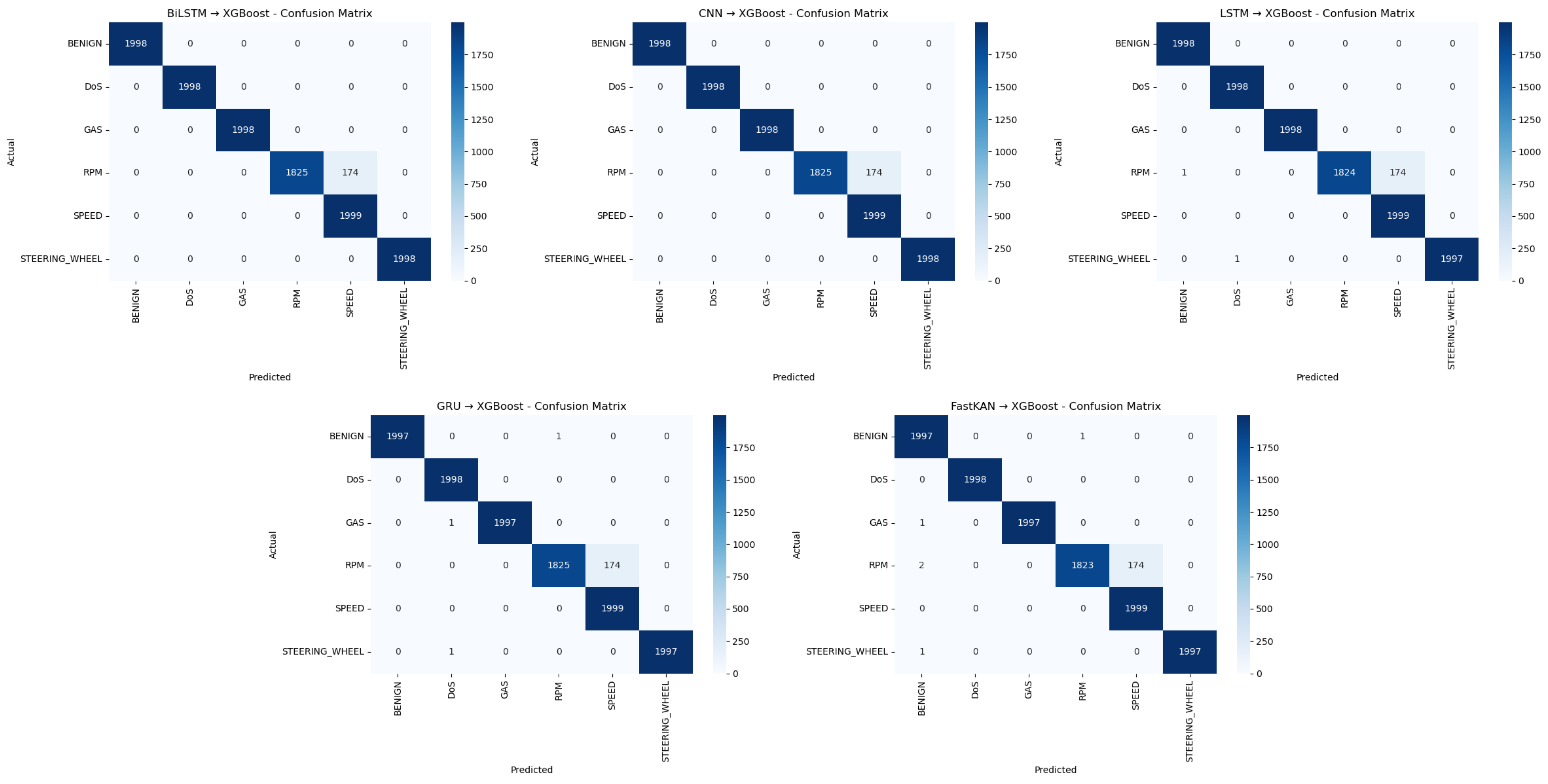

We further assess class-wise behavior using confusion matrices for hybrid approaches on CICIoV2024 (

Figure 7), the primary benchmark guiding our real-time design. We focus on hybrids—rather than standalone DL—because they achieve comparable accuracy with much lower latency (

Figure 7).

The matrices highlight per-class performance for BENIGN, DoS, and spoofing subclasses.

As shown in

Figure 7, all hybrids demonstrate strong classification, with near-perfect detection for BENIGN, DoS, GAS, and SPEED. BiLSTM-XGBoost and CNN-XGBoost yield indistinguishable results, with minor confusions primarily between RPM and SPEED spoofing, suggesting substantial feature overlap for these subclasses. LSTM-XGBoost, GRU-XGBoost, and FastKAN-XGBoost also maintain high accuracy, with slightly higher misclassification concentrated among spoofing categories. Overall misclassified counts remain low, confirming robust discriminative capacity across hybrid variants.

These multi-class predictions are directly actionable at run time: detected

DoS triggers

BLOCK, whereas spoofing subclasses trigger QUARANTINE, ensuring the IDS output drives immediate response. This aligns with the security-engineering view that IDS outputs must support operator action rather than only prediction [

47].

6. Real-Time Hierarchical IDPS Implementation

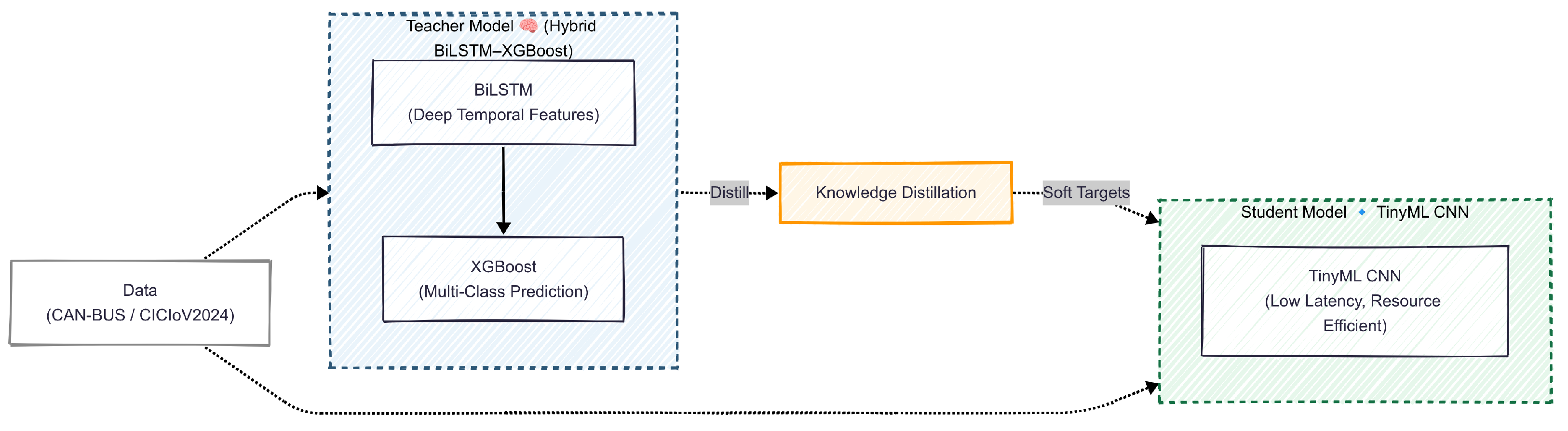

6.1. TinyML Model Deployment

To enable efficient real-time detection on resource-constrained devices, we employ knowledge distillation. A compact TinyML CNN student (student) is trained to replicate the predictive behavior of a larger BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid (teacher). As shown in

Figure 8, the teacher is first trained on windowed CAN bus data, and its output probabilities (soft targets) guide the student CNN. Through this process, the student not only learns to match the teacher’s final predictions but also to approximate the teacher’s confidence in each class, such as predicting 90% traffic overload, 6% spoofing, and 4% benign for a given input. This enables the student to capture subtle inter-class relationships and achieve high accuracy while maintaining low latency and minimal resource use, making it suitable for on-device deployment within the hierarchical IDPS.

The TinyML CNN student model is implemented as a compact 1D convolutional neural network operating directly on the CAN windows used throughout this work. The network comprises two convolutional blocks: the first Conv1D layer applies 32 filters with kernel size 3 and stride 1, followed by a MaxPooling1D layer with pool size 2 to reduce the temporal resolution. The second Conv1D layer applies 64 filters with kernel size 3 (stride 1 by default). Both convolutional layers use ReLU activation. A GlobalAveragePooling1D layer aggregates the resulting temporal feature maps into a 64-dimensional embedding, which is then fed to a final dense layer with 6 units and softmax activation that outputs the per-class probabilities for {BENIGN, DoS, GAS, RPM, SPEED, STEERING_WHEEL}. In total, the TinyML CNN student contains 7398 trainable parameters and occupies approximately in FP32 format, well within the memory budgets of contemporary automotive microcontrollers. Post-training INT8 quantized variants (dynamic and full-integer) further reduce this footprint with negligible loss in accuracy.

Let

and

be teacher and student logits, and let

denote the softmax. With temperature

, define softened distributions

and

.

where

: teacher and student logits (pre-softmax scores).

: softmax function mapping logits to probabilities.

T: temperature parameter ( produces a softer distribution).

: softened teacher and student class-probability distributions.

: Kullback–Leibler divergence.

This transfers calibrated inter-class relations from the RSU teacher (BiLSTM-XGBoost) to the TinyML CNN student. We use pure KD (no hard-label term); teacher probabilities are calibrated (Platt scaling). After training, we apply post-training INT8 quantization for OBU constraints.

In this work, we use a pure knowledge-distillation objective: the on-vehicle TinyML CNN student is optimized solely using the temperature-scaled Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between teacher and student outputs, without adding any cross-entropy term on hard labels. This ensures that the student learns only from the teacher’s calibrated soft targets. During distillation, the TinyML CNN student receives exclusively the BiLSTM-XGBoost teacher’s final output logits and their corresponding temperature-scaled probabilities; no intermediate features, hidden-layer embeddings, or internal representations are distilled. The student is therefore trained entirely on these soft labels rather than on the original ground-truth labels, ensuring that it inherits the teacher’s calibrated decision boundaries rather than functioning as an independently trained small CNN.

For completeness, we compare the distilled TinyML CNN to an identical non-distilled small CNN trained only on hard labels. The non-distilled CNN achieves similar accuracy (0.9964) but does not inherit the calibrated decision boundaries of the BiLSTM-XGBoost teacher and exhibits higher output variance across spoofing subclasses. In contrast, the distilled student matches the teacher’s soft targets, maintains the same accuracy, and achieves a compact 119 kB footprint, confirming the benefit of distillation over an independently trained small CNN.

Distilling from the BiLSTM-XGBoost teacher ensures the TinyML CNN student reproduces the teacher’s calibrated probability distributions and decision boundaries, yielding tier-aligned confidence scores for escalation while meeting strict memory and latency budgets.

In addition to knowledge distillation, we further optimize the TinyML CNN student through model quantization to ensure deployment feasibility on microcontroller-based platforms such as Arduino. Specifically, we apply both static quantization with max calibration and dynamic quantization. Static quantization precomputes scaling factors for weights and activations using a representative dataset, yielding predictable inference behavior, while dynamic quantization quantizes weights ahead of time and computes activation scales on the fly. These techniques significantly reduce the model’s memory footprint with negligible loss in detection accuracy.

The TinyML CNN student is deployed as a static inference-only model within the OBU; its predictions are subsequently revalidated at the RSU tier. Explicit OTA security mechanisms and adversarial defenses are not included in this version and are planned as future enhancements.

6.2. Real-Time Pipeline: Kafka–Spark for Streaming and Classification

Deploying the hierarchical IDPS in real-time requires a robust, scalable pipeline capable of ingesting, processing, and classifying vehicular network traffic at low latency. We adopt a distributed streaming architecture built upon Apache Kafka and Apache Spark, two well-established platforms for real-time big-data analytics in industrial and SC settings [

48]. This choice aligns with recent distributed, microservice-based deployments and big-data benchmarking results [

49,

50], while practical guidance on stream cleaning and windowing further supports the configuration [

51].

6.2.1. Kafka-Based Data Ingestion

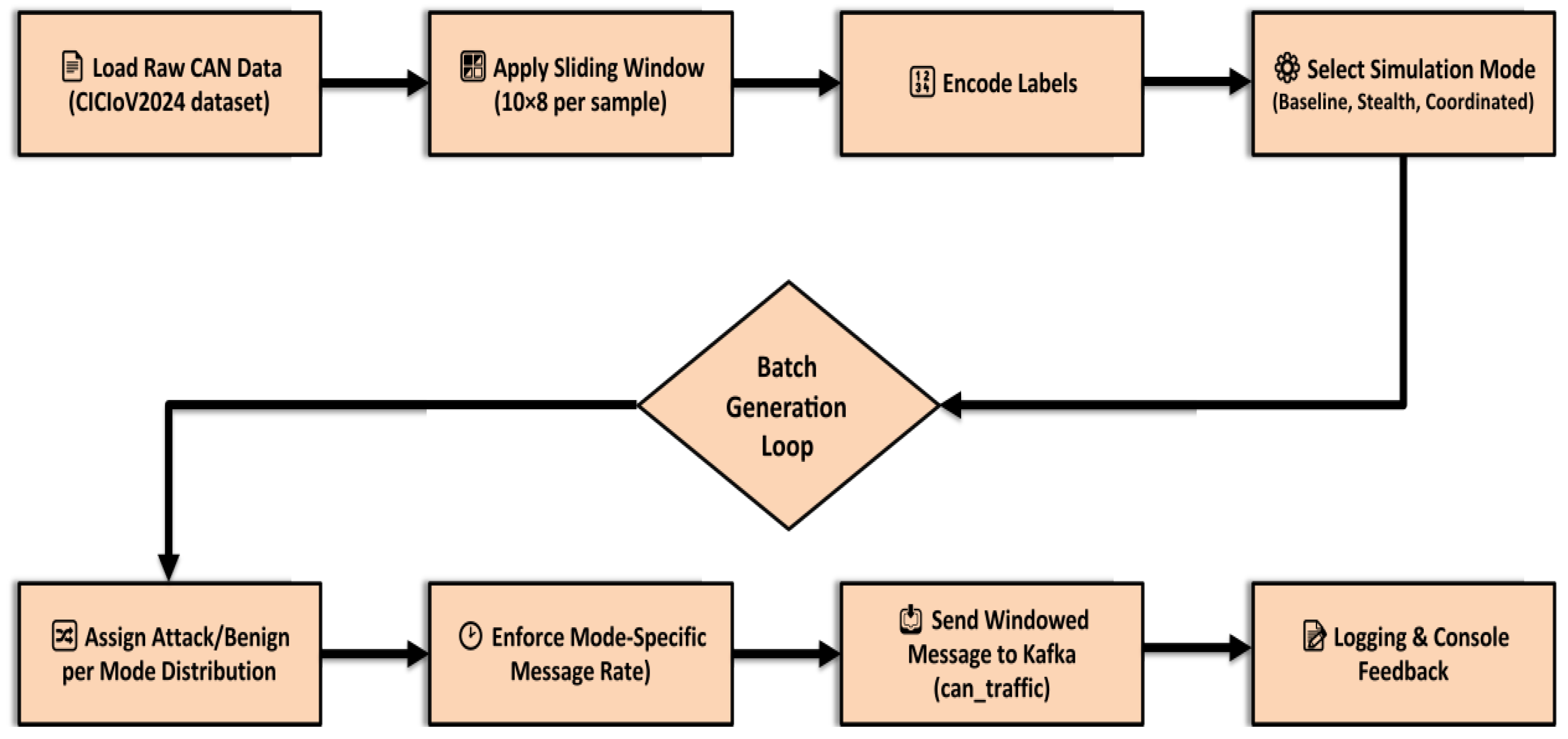

The first step is the generation and streaming of realistic vehicular CAN bus data using a Kafka-based traffic producer implemented in Python. The producer emulates diverse traffic conditions and attack scenarios typical of SC-IoV environments.

System overview:

Raw data loading: The producer reads raw CAN bus messages from CSV files in CICIoV2024. These files are not pre-windowed; the script applies normalization and generates 10-message sliding windows on the fly to reflect temporal structure in real CAN traffic.

Data preprocessing: All numerical CAN features (DATA_0 to DATA_7) are normalized using a standard scaler. Consecutive frames are grouped into windows of 10 messages to capture short-term temporal patterns relevant for detection.

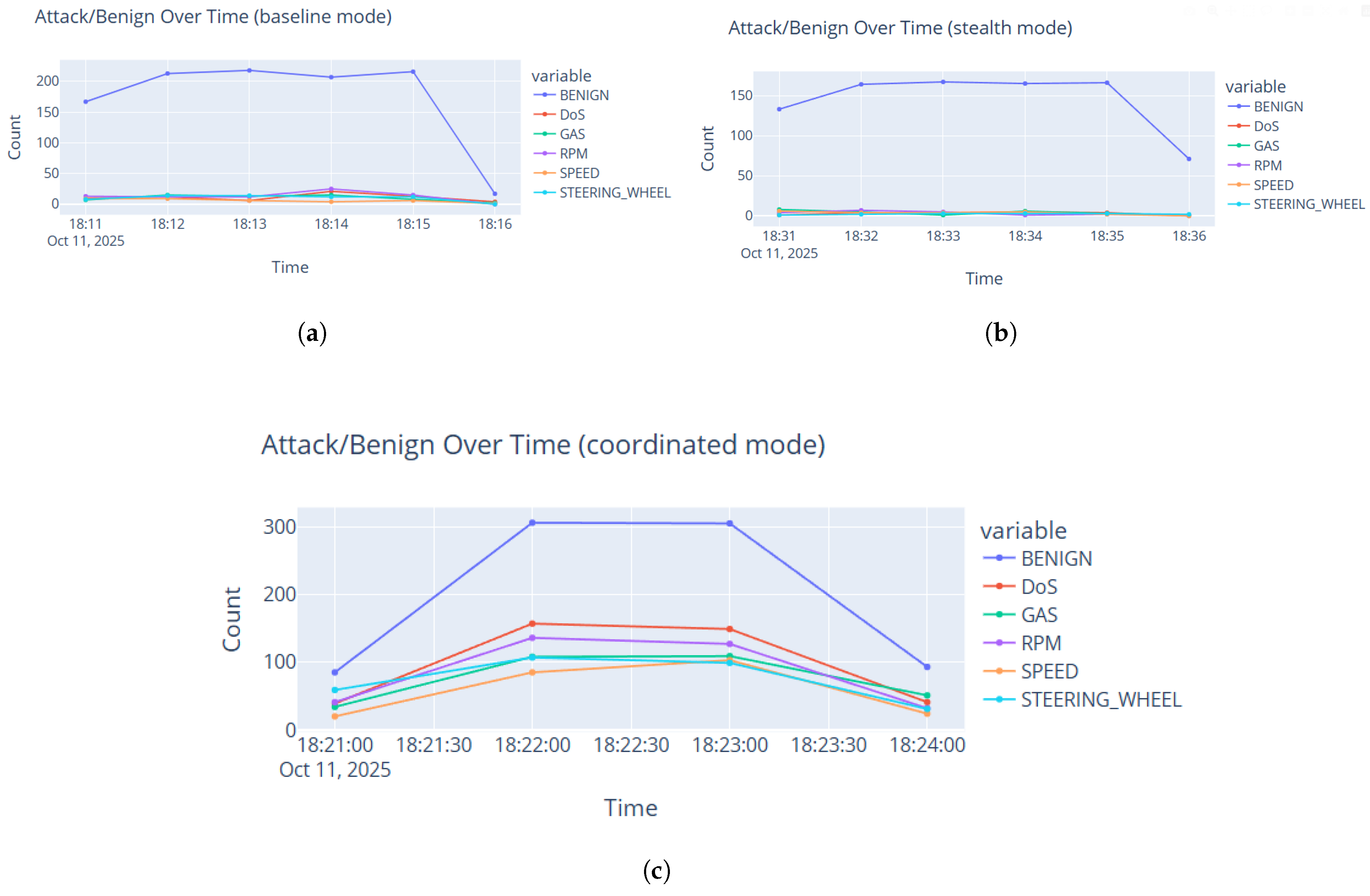

Configurable modes: The producer supports three simulation modes: Baseline, Stealth, and Coordinated (see

Table 4). Each mode specifies (i) the benign/attack mix, (ii) the message rate (messages/s), and (iii) the frequency and intensity of attacks. Operators can switch between normal, stealthy, and high-stress conditions via a single command-line argument.

Windowed message streaming: Each Kafka message contains a sliding window of 10 normalized CAN frames, a majority-vote label, and a timestamp, mimicking real-time vehicular data streaming in a smart city.

Flexible parameters: Command-line arguments control the traffic mode, message rate, random seed, and related options, yielding a reproducible setup adaptable to new datasets or network conditions.

Key points:

The producer ingests raw source data, performs preprocessing and windowing internally, and streams directly to Kafka for real-time analysis.

Operational modes (Baseline, Stealth, and Coordinated) modulate traffic realism and attack diversity.

The setup enables rigorous stress-testing of the downstream Spark-based classifier under reproducible, realistic SC traffic conditions.

Implementation details:

Table 10 summarizes key parameters and defaults for the Kafka traffic producer.

After CAN bus windows are streamed to Kafka, Spark Streaming performs real-time processing and classification, enabling low-latency detection at the RSU tier.

6.2.2. Spark-Based Real-Time Classification

After data is streamed to Kafka, the next stage performs high-speed classification and prevention via a Spark Streaming consumer tightly integrated with the BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid.

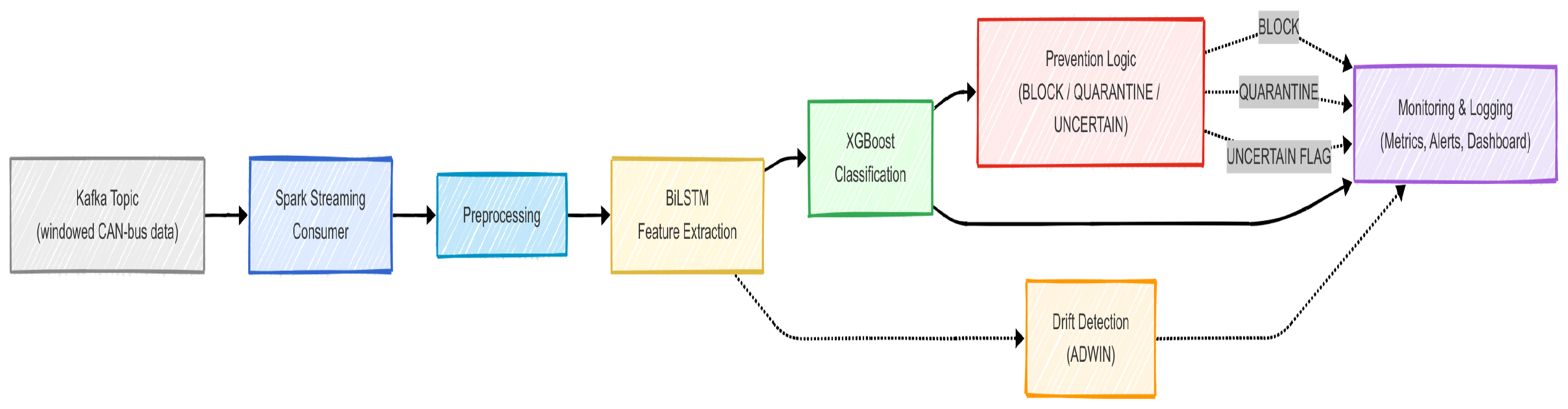

Architecture and workflow.

Real-time ingestion. Spark reads each windowed CAN bus message from the Kafka topic, preserving order and structure.

Feature extraction. Each window is passed through a pre-trained BiLSTM to obtain temporal features that help distinguish benign from malicious behavior.

Attack prediction. XGBoost classifies the extracted features as benign, traffic overload, or a spoofing subclass, combining sequence modeling with fast, accurate inference.

Prevention actions. Based on the prediction:

- –

If a traffic overload attack is detected, the source is blocked.

- –

For spoofing attacks, the responsible device is quarantined and an alert is raised.

- –

Low-confidence events are flagged for review.

Drift detection. ADWIN monitors for concept drift; detected shifts are logged to support subsequent model updates.

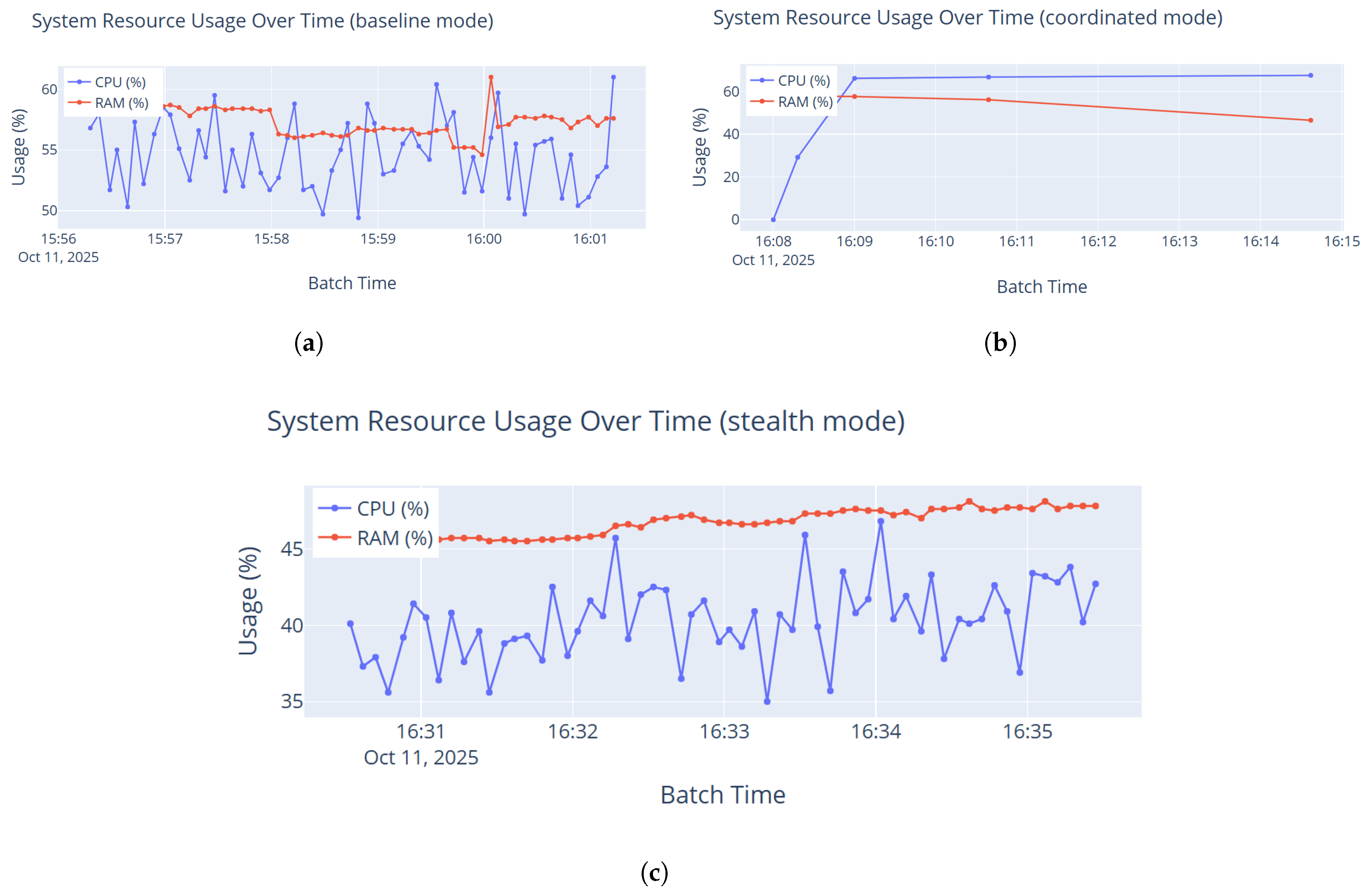

Monitoring and logging. For every processed batch, the system records accuracy, latency, CPU/RAM usage, and attack counts; these are persisted and visualized on the dashboard.

The overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 10.

We model the residual jitter as zero-mean with finite variance:

and

.

Measured latency: From streaming logs, we obtain

= 148.67 ms with residual jitter

= 0.12 ms, yielding an ≈95% prediction band of 148.67 ± 0.24 ms. Component means:

= 9.77 ms,

= 134.61 ms,

= 1.80 ms,

= 0.00 ms.

The reported e2e latency of 148.67 ms was obtained in a local RSU-simulated setup running Kafka and Spark Streaming on a single laptop. In this environment, the dominant factor is the Kafka–Spark micro-batch processing overhead, while the XGBoost inference step contributes only ≈10–13 ms. Because no physical RSU–vehicle wireless link was deployed, network delay is negligible. Under higher traffic density, latency growth is mainly driven by Spark scheduling and queue buildup, whereas inference time remains effectively constant.

Here,

(BiLSTM encoding) and

(XGBoost inference) are measured per micro-batch. Let

be the input rate and

the sustained processing rate. Stability requires

; otherwise the Kafka lag

grows approximately as

where

: e2e latency per window (ingest → features → classify → action), measured in ms.

: ingestion/serialization + Kafka → Spark handoff time (ms).

: BiLSTM feature-extraction time (per micro-batch, ms).

: XGBoost inference time (per micro-batch, ms).

: prevention/alert action time (logging, block/quarantine trigger; ms).

: stochastic synchronization/jitter term (e.g., brief Kafka lag, scheduler jitter); is its standard deviation.

: input arrival rate (windows/s).

: sustained processing rate (windows/s).

: Kafka consumer lag at time t (messages/windows behind the head).

: change in lag over interval (s); positive when backlog accumulates.

Equation (

10) is surfaced on the dashboard’s Kafka-lag (

Section 7).

Key benefits: The Spark-based stage analyzes each message upon arrival, enabling millisecond-scale reaction times. The combination of deep feature extraction and fast classification provides both high accuracy and the speed needed for deployment at SC intersections, while built-in prevention and monitoring maintain operator situational awareness under evolving threats.

Table 11 outlines the real-time Spark consumer configuration, including models, prevention logic, logging outputs, and resource monitoring.

Table 11.

Spark-based real-time consumer configuration parameters.

Table 11.

Spark-based real-time consumer configuration parameters.

| Component | Description | Value/Setting |

|---|

| Kafka Topic | Kafka topic subscribed for CAN bus message ingestion. | can_traffic |

| Consumer Group ID | Kafka consumer group used for offset tracking. | test-consumer-group |

| Batch Interval | Time between batch processing cycles. | 5 s |

| Window Shape | Shape of each incoming CAN message window. | (10, 8) |

| Feature Extractor | Deep temporal feature extractor model. | BiLSTM (last dense layer output) |

| Classifier | Final prediction model used on extracted features. | XGBoost |

| Uncertainty Threshold | Confidence threshold to flag low-confidence predictions. | 0.6 |

| Drift Detection | Online concept drift detection mechanism. | ADWIN (river) |

| Prevention Actions | Policy for detected threats. | BLOCK for traffic overload, QUARANTINE for spoofing |

| Resource Monitoring | System metrics captured per batch. | CPU %, RAM %, latency |

| Per-Batch Metrics | Evaluation metrics calculated each batch. | Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score |

| Prediction Logs | File storing all classification and action results. | predictions_log.csv |

| Action Logs | File logging non-benign actions taken. | actions_log.csv |

| Drift Logs | File tracking detected drift events. | drift_log.csv |

| Batch Logs | File summarizing each batch’s statistics. | batch_log.csv |

| Error Logs | File recording shape mismatches or processing failures. | error_log.csv |

6.2.3. Dashboard Visualization and Real-Time Monitoring

The final component is a web-based dashboard that assists operators in monitoring detection results, analyzing trends, and reacting to threats in real time. Built with the Dash framework, it integrates logs generated by the Spark consumer and the Kafka lag tracker.

Key features:

Time and mode filtering. Filter views by preset time windows (e.g., last 5 min, last hour) and by simulation mode (Baseline, Stealth, and Coordinated).

Kafka lag monitoring. A gauge and time series display lag deltas for early detection of bottlenecks or consumer delay.

Evaluation metrics. Bar charts present per-batch and latest accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score over time.

Traffic analysis. Class distribution, benign vs. attack ratios, and attack-frequency timelines provide insight into threat intensity.

Prevention effectiveness. Donut and heatmap charts summarize BLOCK/QUARANTINE actions and their association with attack types.

System health. CPU and RAM usage, prediction latency, and throughput are tracked per batch.

Drift and uncertainty. Concept drift (ADWIN) and low-confidence rates are visualized over time.

Error and alert management. Error trends and toast-style alerts notify operators of attack surges, drift, or Kafka lag anomalies.

Prediction logs. A live table lists recent classifications (timestamp, mode, predicted label, confidence, action, and latency).

Figure 11 illustrates a representative snapshot during baseline mode: over 4200 messages were processed with near-perfect accuracy across most batches; Kafka lag remained low and stable; and batch latency stayed below 155 ms. Real-time visualizations (class-wise predictions, attack proportions, and actions taken) provide interpretable insight into live behavior. During baseline testing, no error events or concept drift were triggered, yielding empty charts for those components and indicating stable operation under normal traffic.

Implementation overview. The dashboard consumes locally stored logs from the Spark consumer and Kafka lag tracker:

predictions_log.csv—model predictions and confidence scores.

actions_log.csv—records of blocks and quarantines.

drift_log.csv—concept drift detections.

batch_log.csv—per-batch metrics (accuracy, CPU, latency, and throughput).

kafka_lag_delta_history.csv—Kafka lag over time.

error_log.csv—system errors or mismatches.

Table 12 summarizes the key parameters and input files used by the dashboard, including update intervals, log sources, filtering options, and alert conditions.

The dashboard refreshes every 5 s, providing continuous status visibility and early indication of anomalies.

Table 13 presents the main tools, libraries, and system specifications used to implement the real-time hierarchical IDPS, covering traffic simulation, stream processing, model inference, drift detection, and dashboard visualization.

8. Limitations, Open Issues, and Future Directions

Despite achieving strong performance, the proposed H-RT-IDPS has several limitations. The current system is restricted to detecting traffic overload and spoofing (GAS, RPM, SPEED, and steering wheel), while other prevalent IoV threats such as RSU impersonation, MITM, Sybil, and adversarial attacks remain outside its present scope. This focus was intentional: traffic overload and spoofing directly compromise two fundamental IoV security pillars—availability and integrity/authenticity—and are well represented in the CICIoV2024 dataset, enabling rigorous benchmarking and real-time validation.

Another limitation concerns the dataset itself. The system relies on simulated CICIoV2024 traces, and its behavior in real vehicular environments with heterogeneous driving patterns, weather conditions, and hardware imperfections remains untested.

Furthermore, the results reported in this work reflect the CAN configuration present in CICIoV2024, which corresponds to a specific vehicle platform. Different vehicles may employ distinct CAN-ID layouts, payload encodings, and timing characteristics. Such variability can affect both the on-vehicle TinyML CNN student and the BiLSTM-XGBoost hybrid model if deployed without adaptation. In practice, generalizing the system to other vehicle models would require retraining or calibration using that vehicle’s CAN traces or applying domain-adaptation mechanisms. Exploring cross-vehicle generalization therefore represents an important direction for future research.

Scalability is another concern. All real-time experiments were conducted on a single-node Kafka–Spark setup with moderate hardware resources. While the pipeline demonstrated stable performance and low latency, city-scale deployments with dozens of RSUs and thousands of vehicles will require distributed scheduling, load balancing, and resilience mechanisms that were not evaluated in this study. Similarly, current prevention actions (blocking and quarantining) are deliberately simple and do not yet include coordinated multi-RSU decisions, adaptive firewalls, or long-term threat correlation.

Future extensions will expand the framework to cover additional IoV attack families, incorporate adaptive retraining at the edge, and adopt secure coordination mechanisms such as blockchain for tamper-resistant logging and inter-RSU trust.

Recent research on distributed IoV security has explored complementary directions such as federated learning (FL) and blockchain-based coordination. FL-based IDS frameworks for vehicular networks [

54,

55] enable collaborative model updates across vehicles and RSUs without sharing raw CAN traces, improving privacy but incurring additional communication overhead and lacking real-time guarantees.

Likewise, blockchain-enabled IoV security [

56,

57] provides tamper-resistant logging and trust management, yet these systems often omit high-frequency IDS inference or do not operate on constrained OBUs. In contrast, the proposed H-RT-IDPS focuses on hierarchical, real-time detection with TinyML CNN student and RSU-tier BiLSTM-XGBoost inference—rather than distributed training or immutable logging. FL and blockchain therefore represent complementary directions for future integration, such as federated model aggregation for adaptive retraining and blockchain-backed auditability of RSU decisions.