Model Predictive Load Frequency Control for Virtual Power Plants: A Mixed Time- and Event-Triggered Approach Dependent on Performance Standard

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Formulation

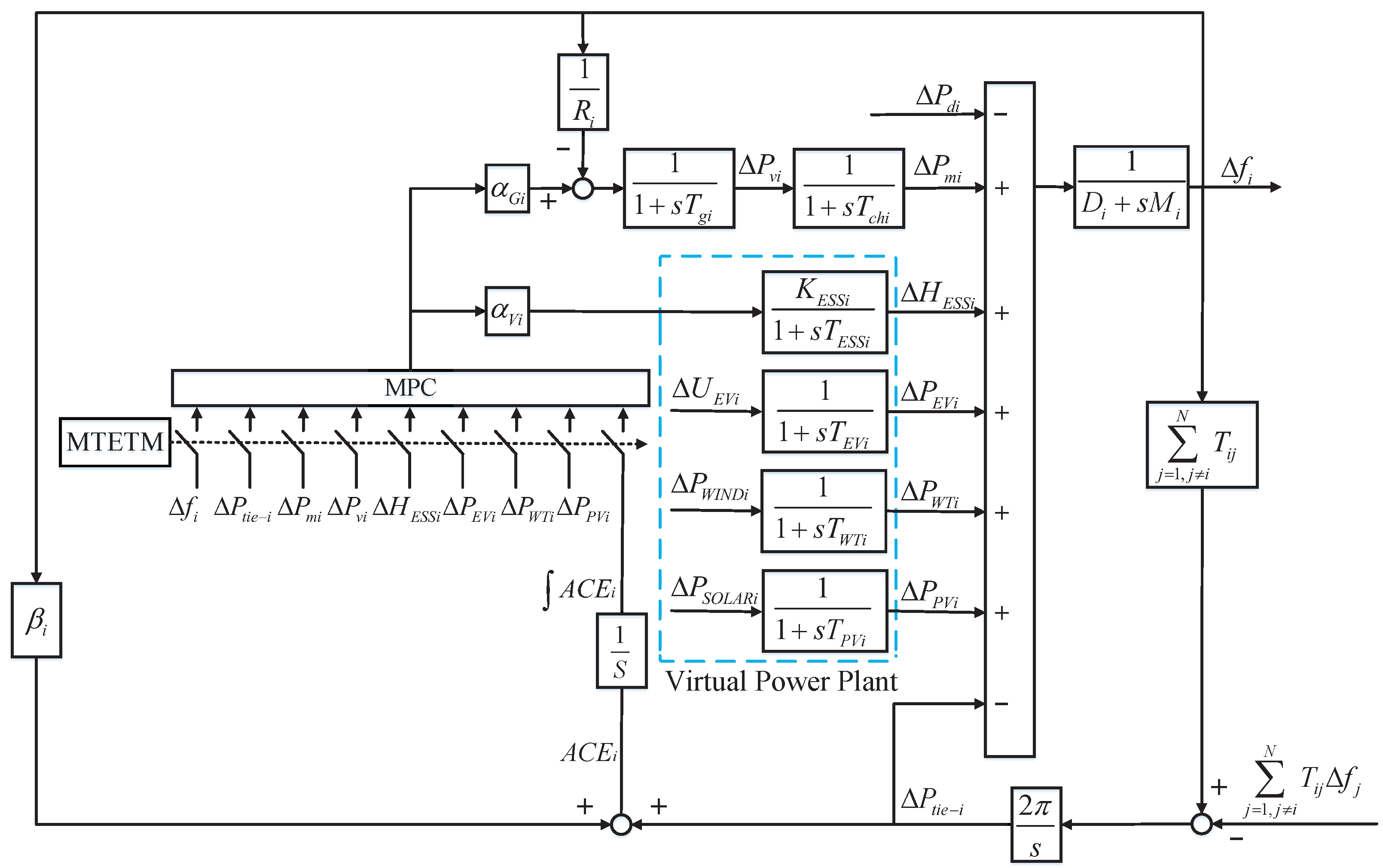

2.1. Overall Structure of Virtual Power Plant

2.2. Energy Storage Systems Modelling

2.3. Electric Vehicle Modelling

2.4. Wind Power Modelling

2.5. Photovoltaic Power Modelling

2.6. Model Predictive LFC Model with Participation of VPP

3. Results

3.1. Auxiliary OP for

3.2. PIS Guaranteeing Conditions

| Algorithm 1: MTETM-based MPC for system (16) |

|

3.3. Recursive Feasibility and Stability Analysis

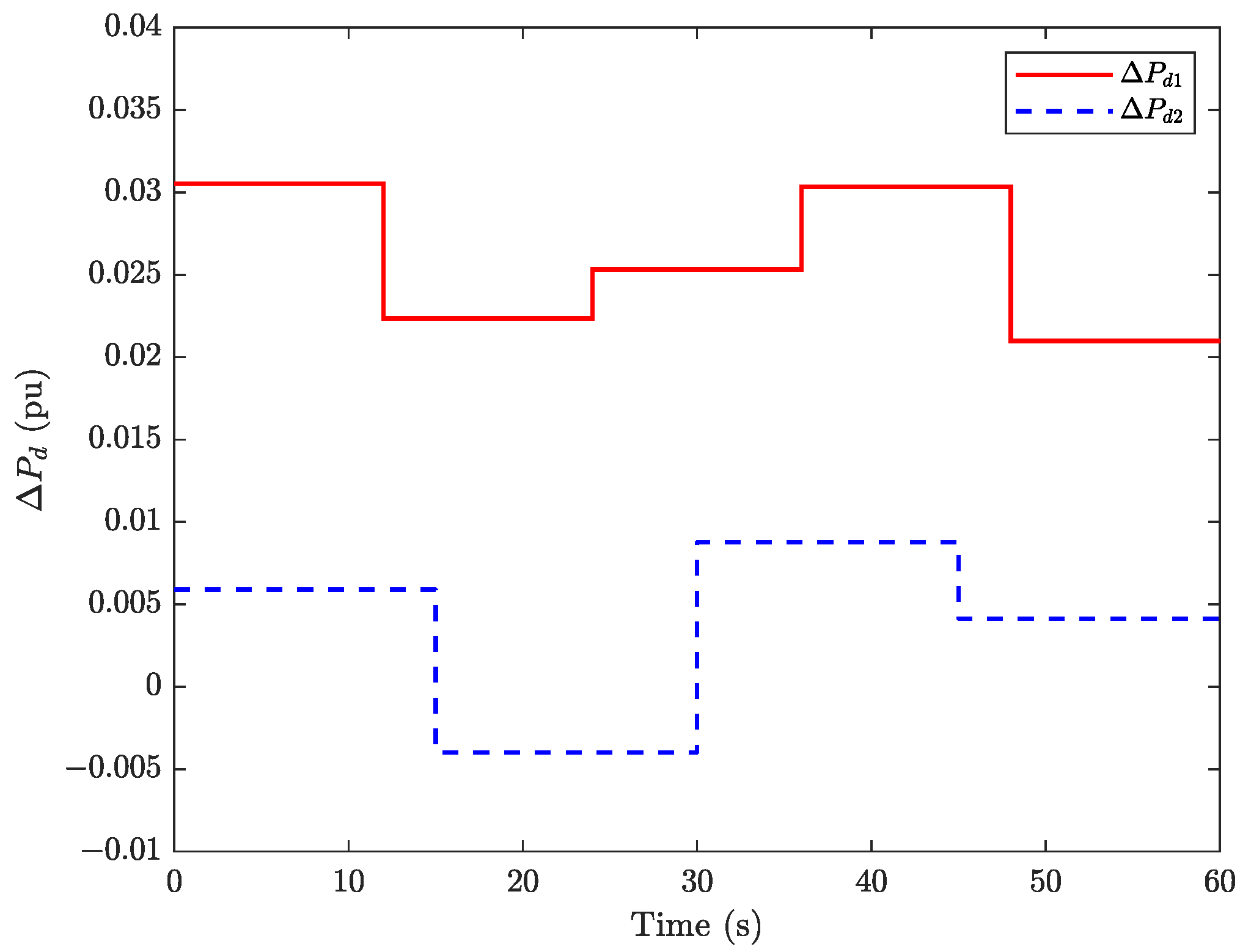

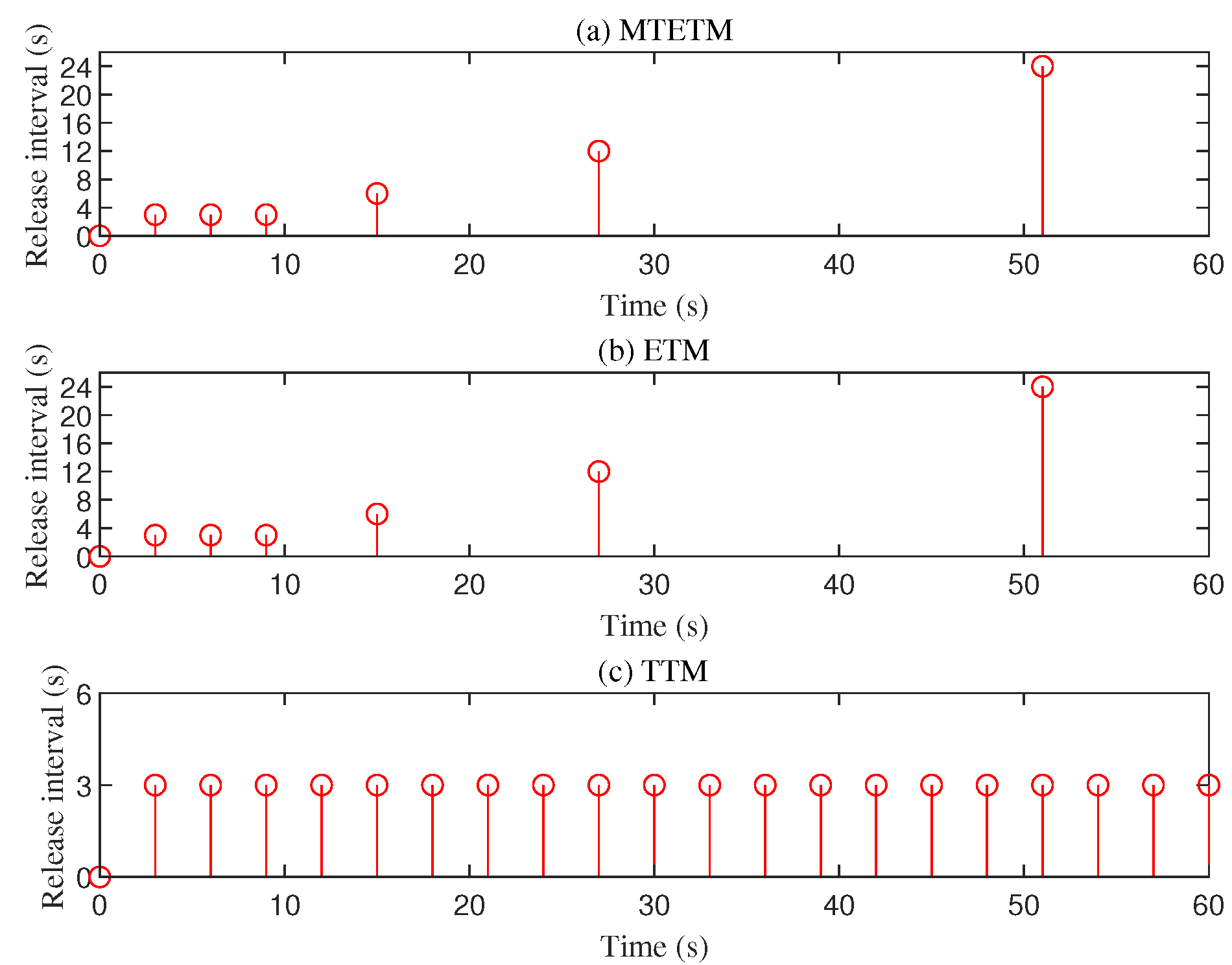

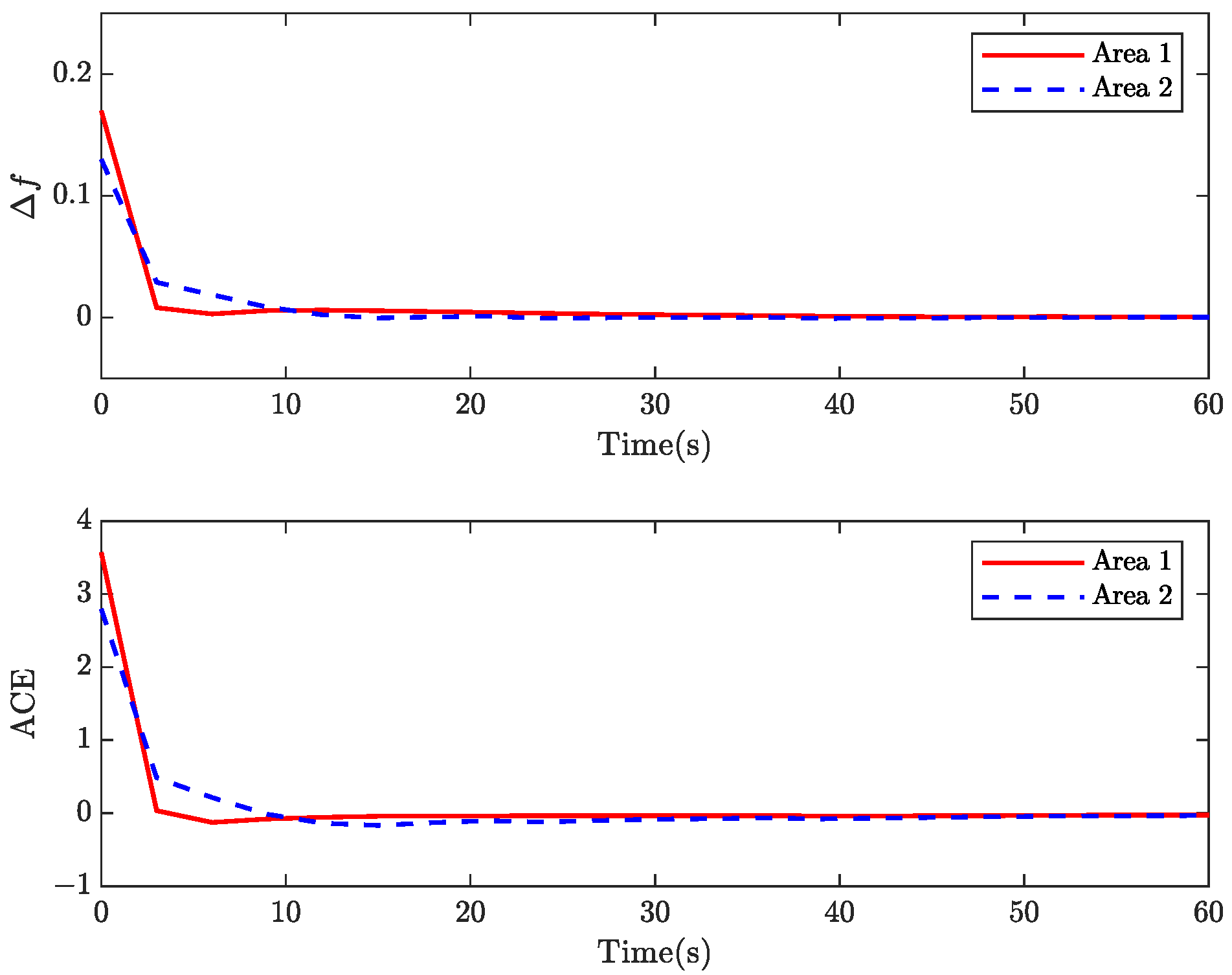

4. Case Analysis

5. Model Usability

5.1. Application Analysis

5.2. Advantages and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Symbols

| VPP | Virtual power plant |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| ESS | Energy storage system |

| LFC | Load frequency control |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| ETM | Event-triggered mechanism |

| MTETM | Mixed time/event-triggered mechanism |

| CPS | Control performance standard |

| OP | Optimisation problem |

| TTM | Time-triggered mechanism |

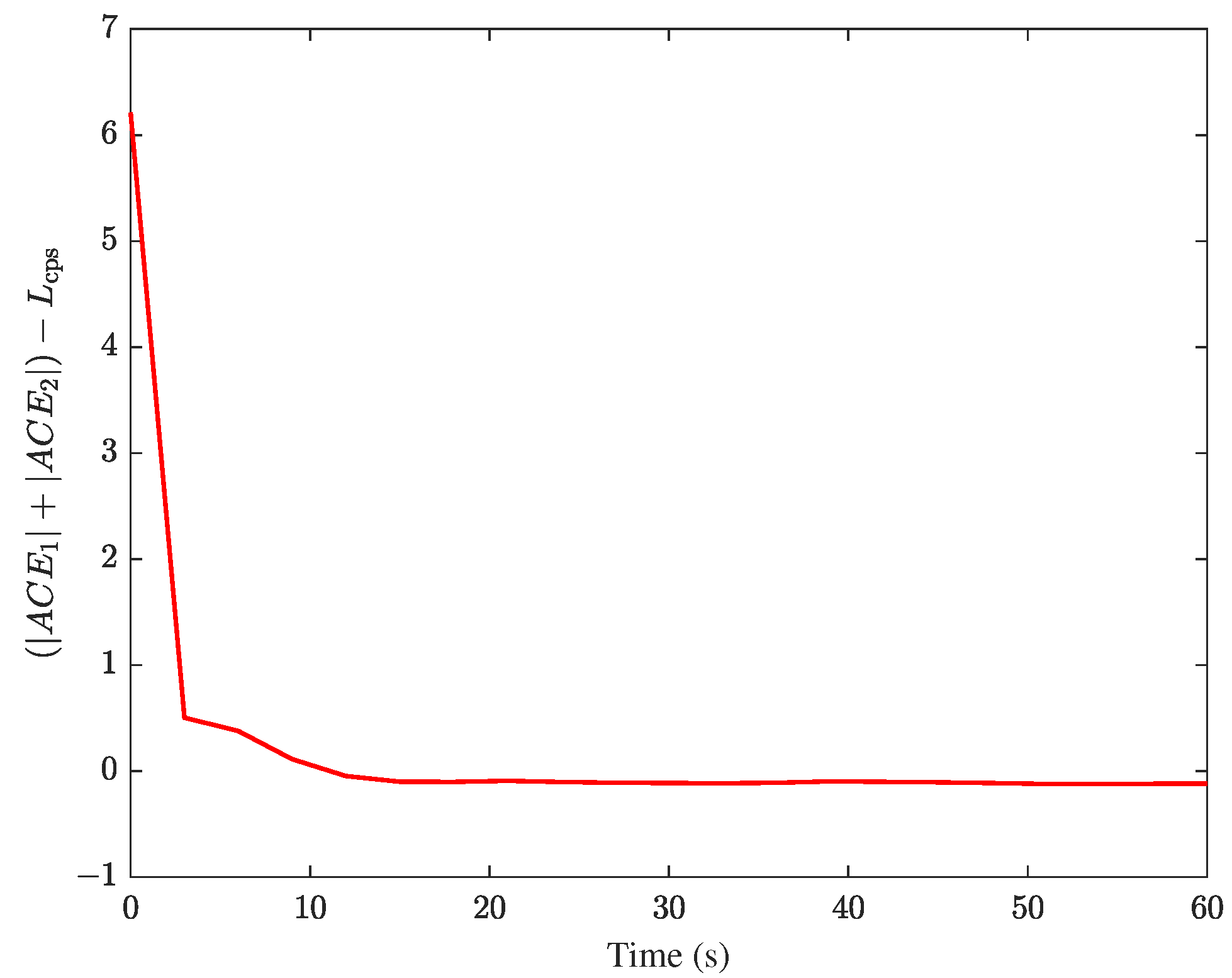

| ACE | Area control error |

| IDV | Internal dynamic variable |

| PIS | Positively invariant set |

| ISS | Input-to-state stable |

| TRs | Triggering rates |

| STAE | The summation of the time multiplied by absolute value of the error |

| SSE | The summation of the square value of the error |

| STSE | The summation of the time multiplied by the square value of the error |

| SAE | The summation of the absolute value of the error |

| Actual system state | |

| The state at the triggering instant | |

| The predicted value at a future instant of state at instant p | |

| Last transmitted state | |

| Error between and | |

| The deviation in the tie-line active power | |

| The deviation in the valve position | |

| The deviation in the generator mechanical output | |

| The deviation in the load disturbance | |

| Time constant of turbine | |

| The deviation in frequency | |

| Tie-line synchronising coefficient between the ith and jth power areas | |

| Time constant of the governor | |

| Area control error | |

| Moment of inertia of generator | |

| Frequency bias factor | |

| Generator damping coefficient | |

| Speed droop |

References

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J. Multi-energy complementary power systems based on solar energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, Z.Y.; Wen, F.; Chen, Q.; Luo, F.; Liu, W. A penalty scheme for mitigating uninstructed deviation of generation outputs from variable renewables in a distribution market. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4056–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaporozhets, A.; Babak, V.; Kulyk, M.; Denysov, V. Novel methodology for determining necessary and sufficient power in integrated power systems based on the forecasted volumes of electricity production. Electricity 2025, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, G.; Chen, S.; Lu, Y.; Xu, K. Control strategy for wind farms-energy storage participation in primary frequency regulation considering wind turbine operation state. Energies 2023, 17, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Li, X.; Jing, X.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, R.; Han, X. Multi-temporal optimization of virtual power plant in energy-frequency regulation market under uncertainties. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, A.A.; Malinowski, M. Iterative genetic algorithm to improve optimization of a residential virtual power plant. Energies 2024, 18, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpîra, H.; Marinescu, B. Enhanced frequency regulation scheme: An online paradigm for dynamic virtual power plant integration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 7227–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, A.; Batmani, Y.; Ahmadi, F.; Bevrani, H. Robust load-frequency control in islanded microgrids: Virtual synchronous generator concept and quantitative feedback theory. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 5408–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Ma, Y.; He, X.; Yang, X.; Gong, J.; Zhao, Y. Robust load frequency control for isolated microgrids based on double-loop compensation. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Wu, J.; Gong, Y.; He, L. An adaptive frequency regulation strategy with high renewable energy participating level for isolated microgrid. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, F.; Bass, O.; Habibi, D. Memory-based adaptive sliding mode load frequency control in interconnected power systems with energy storage. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102515–102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Yang, F.; Tian, E. Event-triggered T-S fuzzy load frequency control with variable probabilistic release for renewable energy integrated power systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 8492–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah Ghadim, H.; Tarafdar Hagh, M.; Ghassem Zadeh, S. Fermat-curve based fuzzy inference system for the fuzzy logic controller performance optimization in load frequency control application. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 2023, 22, 555–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Cui, J.; Liu, X.; Lee, K.Y. Distributed economic model predictive load frequency control for the multiarea interconnected power system with WTs. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, A.; Gómez, J.S.; Llanos, J.; Rute, E.; Sáez, D.; Sumner, M. Distributed predictive control strategy for frequency restoration of microgrids considering optimal dispatch. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 2748–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, T.; Joševski, M.; Gurumurthy, S.K.; Monti, A. Centralized model predictive control for transient frequency control in islanded inverter-based microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.; Heins, T.; Gurumurthy, S.K.; Joševski, M.; Jahn, I.; Monti, A. Distributed model predictive frequency control of inverter-based power systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 53250–53265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Shi, P.; Zhang, H. Model predictive control of distributed networked control systems with quantization and switching topology. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2020, 30, 4584–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Che, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, J. Multi-timescale optimization scheduling of interconnected data centers based on model predictive control. Front. Energy 2024, 18, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, J.; McClellan, A.; Farhat, C.; Pavone, M. Linear reduced-order model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 5980–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Xie, H.; Dai, L.; Xia, Y. Cloud-edge cooperative MPC with event-triggered strategy for large-scale complex systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 31095–31111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Rahmani, M. Distributed moving horizon estimation with event-triggered mechanism for complex networked systems subject to packet dropouts and quantization. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 362, 107988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Hu, S.; Yue, D.; Bu, X.; Ruan, X.; Xu, C. Interval secure event-triggered mechanism for load frequency control active defense against DoS attack. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Su, R.; Ling, K.-V.; Guo, Y.; Ma, R. Resilient event-triggered MPC for load frequency regulation with wind turbines under false data injection attacks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 7073–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Li, S. Periodic event-triggered model predictive control for networked nonlinear uncertain systems with disturbances. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 7501–7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Chang, Z.; Ahn, C.K. Hybrid event-triggered intermittent control for nonlinear multi-agent systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 1975–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yu, W.; Huang, J.; Yu, Y. Model predictive control for switched systems with a novel mixed time/event-triggering mechanism. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2021, 42, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Fridman, E. Event-triggered load frequency control via switching approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 4484–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, K.; Chen, H.; Wen, S.; Yan, H. VSG-LFC on multi-area power system under unsecured communication channel using hybrid trigger mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Enomoto, K. Dynamic analysis of generation control performance standards. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2002, 17, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappachen, A.; Fathima, A.P. NERC’s control performance standards based load frequency controller for a multi area deregulated power system with ANFIS approach. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 2399–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, X.C.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.K.; Jinag, L.; Wu, M. Adjustable event-triggered load frequency control of power systems using control-performance-standard-based fuzzy logic. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 30, 3297–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wan, X.; Zhang, C.K.; Wang, L. A terminal constraint set-dependent mixed time/event-triggered approach to multistep fuzzy MPC. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 606–620. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.B.; Zhou, S.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, W. Delay-dependent stability analysis of load frequency control systems with electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 13645–13653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.; Illindala, M.S. Robust distributed load frequency control for multi-area power systems with photovoltaic and battery energy storage system. Energies 2024, 17, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Adaptive-memory event-triggered load frequency control for multi-input-delay power systems against FDI attacks and sensor faults. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II-Exp. Briefs 2024, 71, 4919–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Wazeer, E.M.; El Masry, S.M.; Abdel Ghany, A.M.; Mosa, M.A. A novel scheme of load frequency control for a multi-microgrids power system utilizing electric vehicles and supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, S.; Izci, D.; Can, O.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V. Frequency regulation of PV-reheat thermal power system via a novel hybrid educational competition optimizer with pattern search and cascaded PDN-PI controller. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102958. [Google Scholar]

- Polajžer, B.; Brezovnik, R.; Ritonja, J. Evaluation of load fequency control performance based on standard deviational ellipses. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Han, T.; An, J.; Wu, M. Fault diagnosis for networked switched systems: An improved dynamic event-based scheme. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 8376–8387. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Fei, M.; Song, Y.; Peng, C.; Du, D.; Sun, Q. Secure adaptive event-triggered control for cyber–physical power systems under denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 1722–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Lu, D.; Wu, Y. Adaptive memory event-triggered load frequency control for multiarea power systems with non-ideal communication channel. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 245, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area 1 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 1.0 | 21 | 10 |

| Area 2 | 0.17 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 1.5 | 21.5 | 12 |

| , | ||||||

| VPP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Area 2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| MTETM (12) | ETM | TTM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRs | 33.3% | 33.3% | 100% |

| Performance Criteria | SAE | SSE | STSE | STAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTETM (12)-based MPC | 28.143 | 63.131 | 16.462 | 201.98 |

| ETM-based MPC | 34.29 | 68.736 | 54.804 | 244.34 |

| TTM-based MPC | 27.958 | 63.135 | 16.38 | 188.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pu, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, S.; Wei, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wan, X. Model Predictive Load Frequency Control for Virtual Power Plants: A Mixed Time- and Event-Triggered Approach Dependent on Performance Standard. Technologies 2025, 13, 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120571

Pu L, Hou J, Wang S, Wei H, Zhu Y, Xu X, Wan X. Model Predictive Load Frequency Control for Virtual Power Plants: A Mixed Time- and Event-Triggered Approach Dependent on Performance Standard. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):571. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120571

Chicago/Turabian StylePu, Liangyi, Jianhua Hou, Song Wang, Haijun Wei, Yanghaoran Zhu, Xiong Xu, and Xiongbo Wan. 2025. "Model Predictive Load Frequency Control for Virtual Power Plants: A Mixed Time- and Event-Triggered Approach Dependent on Performance Standard" Technologies 13, no. 12: 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120571

APA StylePu, L., Hou, J., Wang, S., Wei, H., Zhu, Y., Xu, X., & Wan, X. (2025). Model Predictive Load Frequency Control for Virtual Power Plants: A Mixed Time- and Event-Triggered Approach Dependent on Performance Standard. Technologies, 13(12), 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120571