1. Introduction

In the field of agriculture, contemporary computational methodologies are being utilised with increasing frequency, thereby facilitating a more profound comprehension of the intricate physical processes that transpire during soil tillage, harvesting, and grain handling. The Discrete Element Method (DEM), which was introduced in 1979 by Cundall and Strack [

1], has been demonstrated to be a fundamental tool for simulating the behaviour of granular materials, rendering it particularly relevant for agricultural applications [

2,

3]. The DEM methodology facilitates comprehensive analysis of the movement, interactions and flow of bulk materials, including soil, seeds and fertilisers. This analysis provides insights that are essential for enhancing the efficiency of agricultural processes [

4,

5,

6,

7].

To ensure accurate simulation results, the parameters of the DEM model, such as Young’s modulus, the coefficient of restitution, and the static and dynamic friction coefficients, must first be calibrated [

8,

9]. The determination of these parameters is possible through the implementation of mechanical tests. The resulting model settings are then refined using the Design of Experiment (DoE) method [

10]. In order to ensure that the model’s behaviour corresponds to the actual behaviour of the particulate material, verification approaches have been developed [

11]. According to Pásthy et al. [

12], the verification of DEM models could be conducted through three distinct experiments: firstly, the verification of force effects through tensile forces [

13,

14], secondly, the utilisation of a penetration test, and finally, the verification of the movement of particles in the model. It is evident that the adoption of a highly complex calibration approach is both rational and justifiable. Indeed, this methodology has been proven to result in the development of a model that is both robust and widely applicable. However, in practice, the construction of such a model is exceedingly demanding in terms of time and computational performance [

15], and may exceed the requirements of the specific intended use. Consequently, it is frequently more appropriate to seek a balanced solution and apply a suitable set of methods tailored to the subsequent application [

16].

Verification of force effects by means of tensile forces was conducted in the research of Kuře et al. [

17], who validated a DEM simulation model of sand using an experimental soil bin, through which a plough with various wing geometries was passed. In a related study, Mouazen et al. [

18] employed a movable grooving device equipped with an instrument for measuring soil mechanical resistance to ascertain tensile forces. This device was subsequently applied to validate a finite element method (FEM) simulation, with the aim of determining the maximum force acting on the grooving device as well as the bulk density of dry soil.

Another potential methodology for the calibration of parameters is motion verification [

12]. Common methods include measuring the static or dynamic angle of repose and then comparing it with the model [

19]. To verify DEM models for modeling the flow of bulk materials, Hajivand Dastgerdi et al. [

20] proposed in 2024 the use of model verification of three basic tests: surface friction, bulk density, and the angle of repose measurement. However, these methods provide only limited possibilities for directly verifying the dynamic behavior of the material during the simulated process. A possible approach is the direct observation of material flow, followed by comparison with the model [

21].

Pásthy et al. [

12] in 2024 employed an inertial measurement unit (IMU) to monitor material flow for the validation of a material DEM model. A significant advantage of this approach lies in its ability to enable subsurface tracking. Its limitations, however, include noise and the sudden occurrence of errors that cannot be predicted in advance and that hinder the reliable reconstruction of device movement [

22]. Given the complex nature of particulate behaviour, it is also important to evaluate surface-level dynamics, as particles at the surface often exhibit different motion patterns than those embedded in the bulk [

23]. A possible solution is provided by tracking objects on the surface during the motion of the particulate material through image analysis [

24,

25]. Our previous study [

21], conducted in 2022, focused on observing the motion of rapeseed particles during the discharge process using a camera. The observations were performed with an experimental apparatus specifically designed to determine the angle of repose. To enable the tracking of motion, contrasting points were placed on the surface of a transparent cylinder containing the flowing material. This method proved to be effective, but only a single camera was used. Tracking objects with two cameras is more complex and requires more advanced techniques. This was implemented in our previous study from 2024 [

26]. In that study, the motion of contrasting markers was observed during the passage of the tool through the soil bin at a velocity of 0.1 m·s

−1. While the methodology was found to be suitable for validating particle motion on the surface of particulate material in DEM models, the applied tool travel velocity did not correspond to actual velocities in medium-depth tillage. For medium-depth tillage (150–300 mm), machine travel velocities between 4 km·h

−1 and 10 km·h

−1 are commonly used [

27,

28]. A significant drawback of many studies focused on model validation of material flow is that they are carried out under laboratory conditions, which do not allow field conditions to be preserved [

17,

29], including the aforementioned tool travel velocity. Field testing prevents the degradation of the particulate material sample intended for laboratory experiments, which is caused by handling and transportation of the material [

30]. Study described in this paper builds upon our previous research [

26]. The earlier study was limited to very low tool travel velocity conditions (0.1 m·s

−1), which are not representative of medium depth tillage and do not allow for reliable validation of DEM models intended for real field applications. In contrast, the present study demonstrates, for the first time, that image-based trajectory reconstruction supported by an artificial neural network can be applied at realistic tool travel velocities of 1.0 and 1.5 m·s

−1 and with a full-scale agricultural tool.

Our study proposes an approach for DEM model validation using image analysis, with the potential to be implemented under field-like conditions (using a laboratory soil channel with field-representative geometry and operating velocity). The tracking of motion through image analysis can be accomplished with a high degree of efficacy by employing two cameras, a method that facilitates the determination of the real spatial coordinates of specific points. Accurate image-based spatial analysis necessitates the determination of both intrinsic and extrinsic camera parameters [

31,

32]. The extrinsic parameters describe the exact position and orientation of each camera relative to the world coordinate system [

33], while the intrinsic parameters represent the camera’s internal characteristics, including principal point, focal length, and lens distortion coefficients. These parameters compensate for optical imperfections affecting image geometry [

33,

34]. The utilisation of a checkerboard calibration pattern is a customary approach in the precise determination of these parameters, providing a series of well-defined reference points for calibration purposes [

35,

36]. The ChArUco board is characterised by a combination of a checkerboard pattern and ArUco markers. This approach facilitates more reliable and accurate calibration, owing to the enhanced ease and clarity with which reference points can be detected, even in instances of partial occlusion of the pattern [

37].

The determination of object trajectories can be effectively achieved through stereoscopic triangulation, which utilises a pair of cameras to capture different perspectives of the observed scene. By mathematically identifying the intersection points of the projected rays, the three-dimensional positions of tracked objects can be reconstructed [

33,

38].

In recent years, machine learning approaches have increasingly complemented classical computer vision methods in trajectory analysis [

39,

40]. Neural networks are particularly advantageous for modeling nonlinear dependencies between input and output data, such as pixel information recorded from multiple camera viewpoints. When appropriately configured and trained, these models can accurately estimate the spatial locations of tracked particles. This combined approach provides a robust framework for reconstructing motion paths in the

X,

Y, and

Z coordinate dimensions, analogous to full three-dimensional object tracking [

41].

The aim of this study is to design and apply a comprehensive methodology for validating the motion of particulate material modeled using the Discrete Element Method (DEM) in a laboratory soil channel with field-representative geometry and operating velocity, using experimental measurements obtained during controlled soil-processing tests. The proposed approach combines experimental observation with numerical simulation and employs a camera-based tracking system supported by neural network analysis for accurate particle trajectory reconstruction. In this study two custom-developed algorithms were implemented: one designed for rapid trajectory extraction and another for the comparison and selection of trajectories between experimental and simulated data.

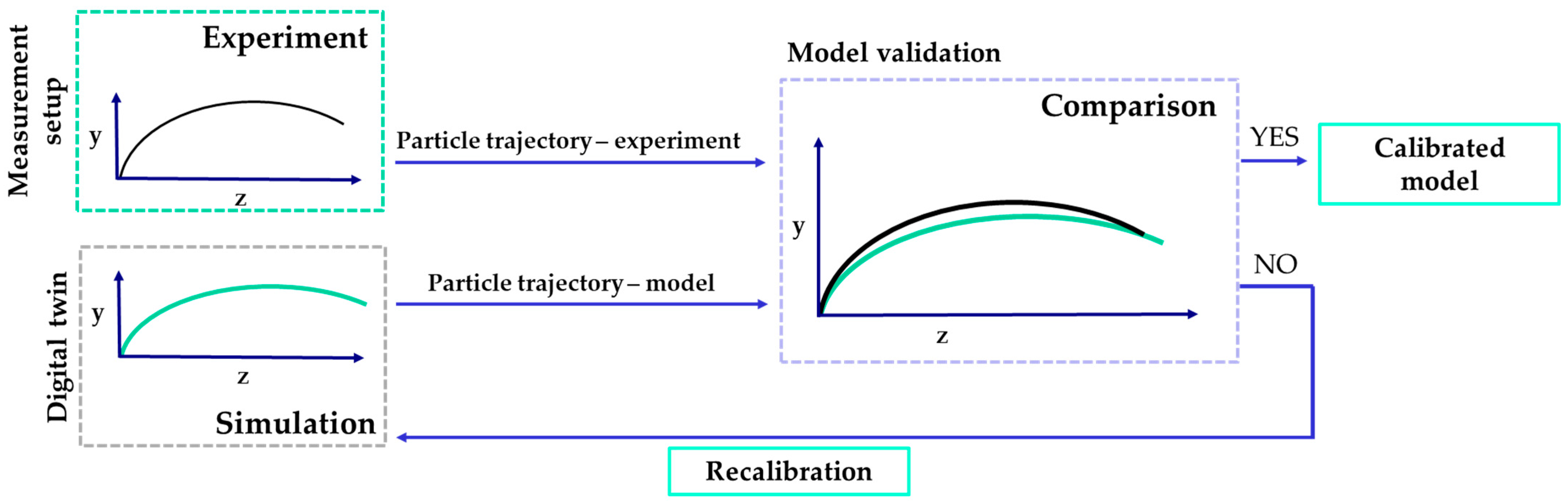

The overall methodological framework is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1, providing a simplified representation of the validation process. The methodology enables the determination and comparison of particle trajectories obtained experimentally and from the corresponding digital twin. This comparison forms the basis for model validation: when the trajectories are consistent, the model is considered calibrated; if discrepancies occur, recalibration is performed to refine model parameters. The proposed approach represents a practical and accessible method for validating particle motion models, with the potential for application under real field conditions and even during the actual process of agricultural soil interaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment and Equipment Used

The experiment was conducted in a laboratory soil channel designed to reproduce conditions representative of real field environments. The apparatus (

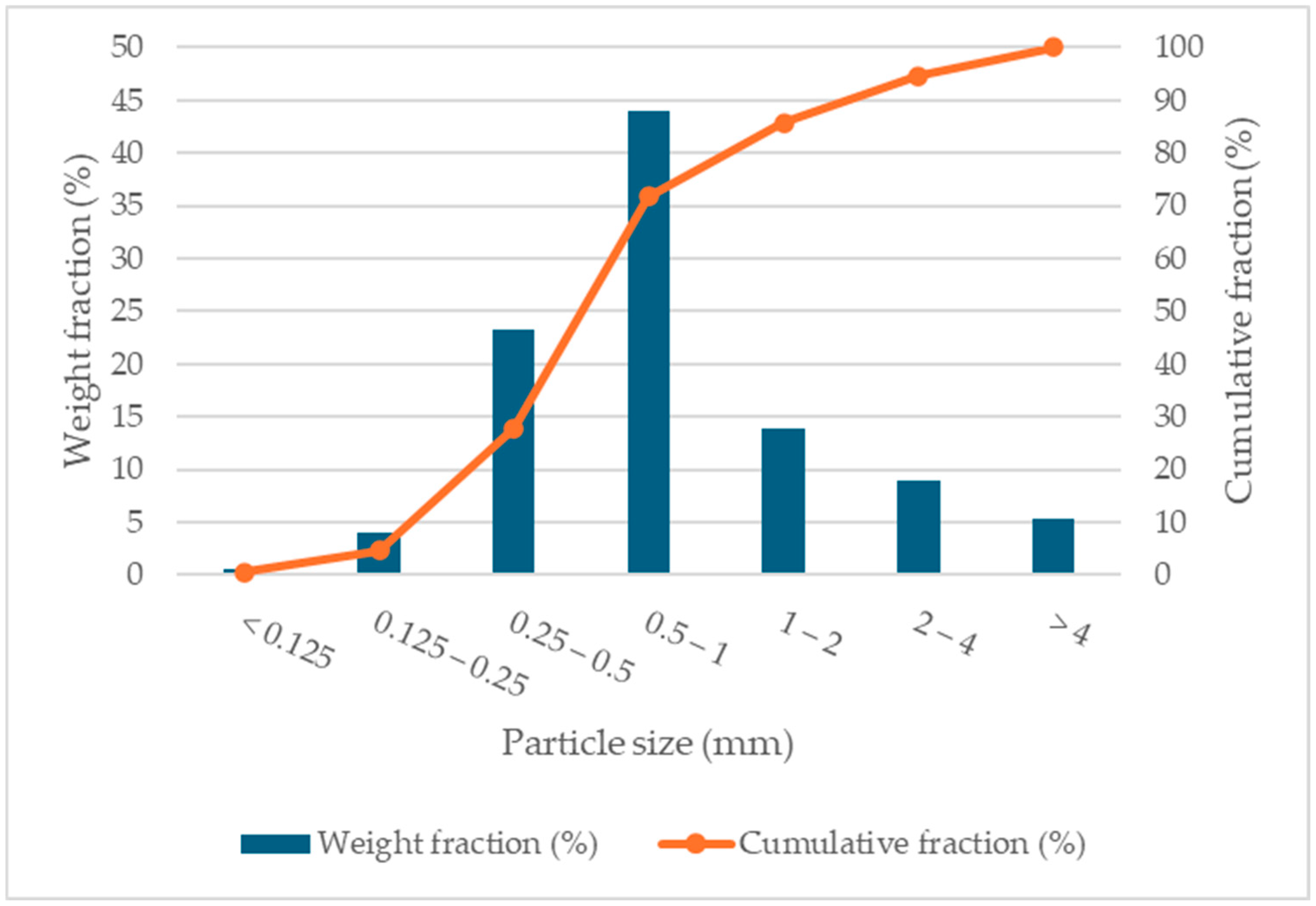

Figure 2) has overall dimensions of 4000 × 10,000 × 3500 mm and includes a movable carriage equipped with tool clamping heads (1). The device allows for adjustable acceleration during the passage of the tool along the track. The channel was filled with excavated sand, whose moisture content at depths corresponding to medium-depth tillage (150–300 mm) was nearly zero, with a measured value of 0.88%.

Figure 2 presents the particle size distribution of the excavated sand, shown as a gradation curve. The tool used for the passages was a steel chisel (2) operating at two translational tool travel velocities: a lower velocity of 1 m·s

−1 and a higher velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1. The penetration depth of the tool below the surface of the particulate material was 184 mm.

An integral part of the experimental setup was the image analysis system, consisting of two GoPro Hero 8 Black (GoPro, Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) cameras (3) mounted on the movable carriage (4), a set of contrasting marker particles (5), and a calibration ChArUco board. The cameras were designated according to their position as Cam 1 (side camera) and Cam 2 (front camera). The cameras recorded the motion of the contrast particles, enabling reconstruction of their trajectories. Both cameras were set to video mode with 4K resolution, 50 FPS, and a linear lens configuration. The contrasting particles were modeled from soft sculpting clay (Alien Clay, Soft—Chavant Inc., Macungie, PA, USA) with an average diameter of approximately 8 mm. The clay spheres used as visual markers were chosen to be as similar as possible to the surrounding sand in terms of density and surface interaction, so that their presence would not disturb the bulk flow. Their function is purely visual, as they are passively transported by the material stream. The main practical limitation is their larger diameter, which can introduce a minor positional uncertainty during image-based centroid detection, but this effect is systematic and minimally influences the physical interpretation of the reconstructed trajectories.

The arrangement of the marker particles followed a regular 1–15 grid pattern (5), with 50 mm spacing along both the

Z-axis (tool travel direction) and the

X-axis (lateral direction). Multiple particles in a single row allowed for multiple resulting paths, eliminating the need for multiple experimental runs. Particles 1–5 were placed directly along the tool travel axis.

Figure 3(6) shows the contrasting particles after the tool passage. The coordinate system illustrated in the figure defines the spatial orientation used for trajectory evaluation, where the

X-axis corresponds to the lateral direction, the

Y-axis represents the vertical direction, and the

Z-axis denotes the direction of tool movement.

2.2. Camera Calibration

For image analysis and the determination of spatial coordinates, camera calibration was required, including both internal (intrinsic) and external (extrinsic) parameters. The overall calibration procedure is schematically illustrated in

Figure 4. The calibration process was performed using a ChArUco checkerboard pattern [

37]. Each camera recorded the calibration board individually, and the video sequences were imported into the Caliscope v.0.6.0 software [

42], which was used to determine both sets of parameters. Because Caliscope required a resolution of 1080 × 1920 px, the original 2160 × 3840 px videos were downscaled before processing.

The ChArUco checkerboard used for calibration consisted of 7 columns and 5 rows, with each square measuring 40.4 mm, resulting in total dimensions of 282.8 × 202 mm. During internal calibration, the inner corners of the individual squares served as reference points that were automatically detected and tracked by the software (

Figure 4, left). A total of 24 reference points were used for the determination of intrinsic parameters. The intrinsic calibration yielded the focal length, optical center (principal point), and lens distortion coefficients (radial and tangential), defining the internal geometry and optical characteristics of each camera.

For the calibration of the external parameters, a synchronized recording from both cameras was obtained while capturing the motion of the ChArUco calibration board placed on the sand surface in the laboratory soil channel (

Figure 4, center). Synchronization of the recordings was achieved using a distinct acoustic impulse (a hand clap) at the start of the video, serving as a common temporal reference. Initially, the board was positioned statically on the surface to establish its initial orientation relative to the coordinate plane, after which it was moved within the overlapping field of view of both cameras to ensure complete spatial coverage.

The synchronized video recordings were processed in Caliscope to determine the external calibration parameters. These extrinsic parameters included the rotation matrix (R), defining the relative orientation between the cameras, and the translation vector (t), representing their spatial displacement in three-dimensional space. Through this procedure, a total of 94,939 spatial data points were obtained, corresponding to the pixel values captured by both cameras.

The final visualization (

Figure 4, right) shows the spatial configuration of the calibrated camera system. In this representation, the side-view field of Cam 1 and the front-view field of Cam 2 are depicted as pyramidal viewing volumes extending from the respective camera lenses toward the calibration board. The pyramid vertices correspond to the actual camera positions. The coordinate system (

X,

Y,

Z), corresponding to that of Cam 1, defines the spatial reference used for trajectory evaluation and reconstruction.

2.3. Tool Passage Settings

The control system of the laboratory soil channel enabled the adjustment of tool travel velocity, trajectory length, acceleration and deceleration times, and other dynamic parameters according to the experimental requirements. The passage of the tool was divided into three phases: acceleration, steady-state travel, and deceleration. At the operating tool travel velocity of 1 m·s−1, the acceleration phase covered a distance of 1000 mm, with an acceleration of 0.5 m·s−2 and a duration of 2 s. During the steady-state phase, the tool travelled over a distance of 3000 mm at a constant velocity of 1 m·s−1, which lasted 3 s. The deceleration phase was performed over a distance of 1000 mm, with an acceleration of −0.5 m·s−2 and a duration of 2 s. In total, the displacement was 5000 mm and the total duration was 7 s.

At the tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s−1, the acceleration phase covered a distance of 1023 mm, with an acceleration of 1.1 m·s−2 and a duration of 1.36 s. During the steady-state phase, the tool travelled over a distance of 2954.55 mm at a constant velocity of 1.5 m·s−1, which lasted 1.97 s. The deceleration phase was performed over a distance of 1023 mm, with an acceleration of −1.1 m·s−2 and a duration of 1.36 s. In total, the displacement was 5000 mm and the total duration was 4.7 s.

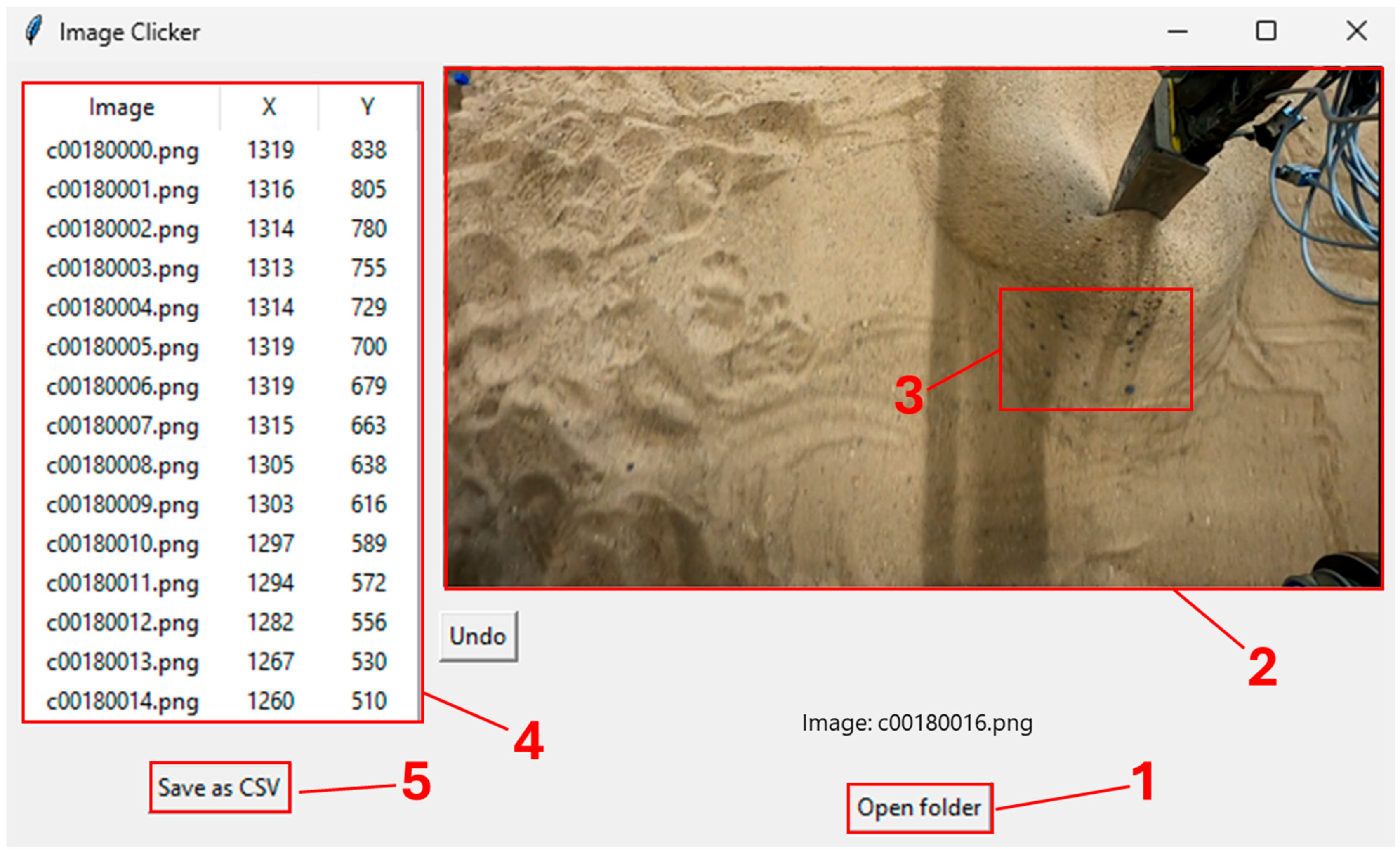

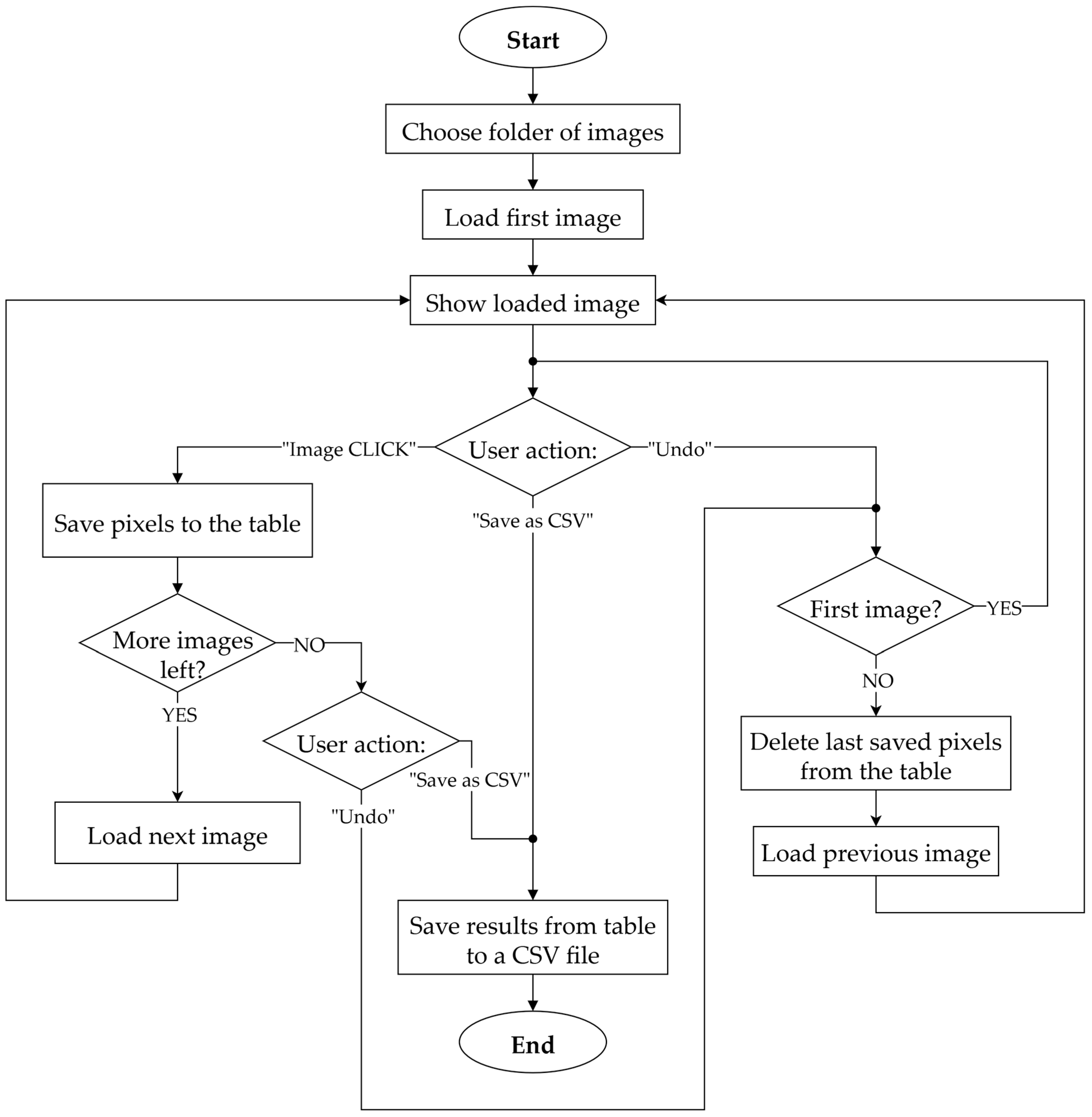

Image Processing—Custom Image Clicker Script

To determine the change in pixel coordinates from the recorded videos obtained after the tool passage, an Image Clicker script was developed in the Python version 3.12.4 environment. The tool was designed for manual tracking of selected contrasting particles within individual frames extracted from previously captured video sequences. The graphical user interface of the application is shown in

Figure 5. The interface allowed the user to select a folder (1) containing the extracted frames from the recorded videos. The selected frame was displayed in the central panel (2), where the particle of interest could be manually selected using the mouse cursor (3). The corresponding pixel coordinates (

X,

Y) of the selected particle were automatically written into a table (4) displayed on the left side of the interface. The recorded coordinates could then be exported and saved as a *.csv file (5) for further analysis. The workflow of the Image Clicker application is schematically illustrated in

Figure 6.

2.4. ANN Development

To transform pixel coordinates obtained from the Image Clicker application into spatial coordinates, a neural network was developed in the Python version 3.12.4 programming environment using TensorFlow and Keras libraries. The network was implemented as a multilayer perceptron (MLP) model trained and tested within the PyCharm 2025.1 environment.

The configuration of the neural network, including the number of hidden layers, neurons, batch size and training epochs, was selected based on a DoE analysis. Several combinations were tested: batch sizes of 64, 128, 256, 512 and 1024, training epochs of 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70, and layer sizes of 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024 and 2048 neurons. The three hidden layer architecture achieved the most accurate and stable performance across the evaluated metrics. The overall model architecture and the DoE-based training configuration, together with the optimisation parameters, are summarised in

Table 1.

The input to the network consisted of two synchronized datasets representing the pixel positions recorded by the side (xs, ys) and front cameras camera (xf, yf), while the target outputs corresponded to the spatial coordinates of the observed points in the global reference frame. The dataset used for training was generated in the Caliscope software and contained a total of 94,939 samples. Pixel coordinates obtained from the Image Clicker application were normalised to the range 0–1 using a Min–Max scaler, and the same normalisation procedure was applied to the target spatial coordinates.

All hidden layers used ReLU activation, while the output layer used a linear activation function suitable for regression. Dropout regularisation with a rate of 0.2 was applied after each hidden layer to reduce overfitting. Early stopping with a patience of 10 epochs, monitoring the validation loss monitoring the validation loss, was applied to prevent overfitting by restoring the best-performing weights. After training, the neural network was used to predict the 3D spatial positions of tracked particles based on pixel coordinates extracted from the experimental video recordings using the Image Clicker tool.

2.5. Custom Script for the Data Selection from the Model

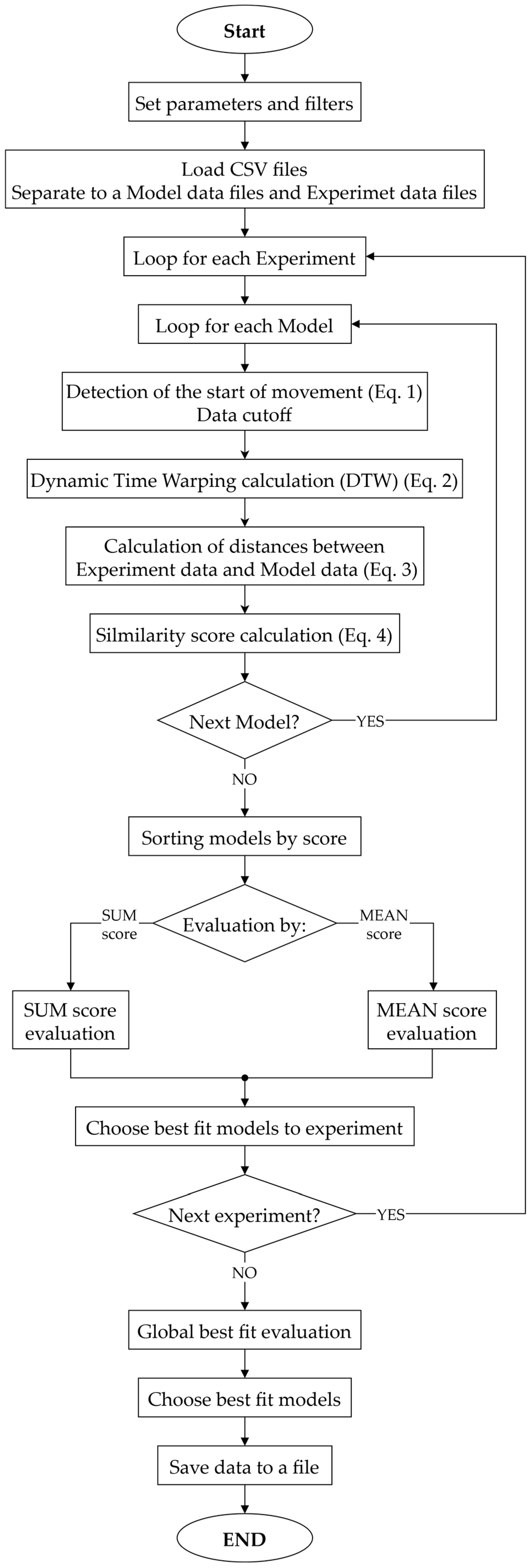

Since it is necessary to process and compare a large amount of data, a custom Python script (version 3.12.4) was developed to compare the data obtained from numerical simulations with experimental measurements and to visualize the results. The script enables automated comparison of particle trajectories between experimental data and model simulations. The main objective was to quantify the degree of agreement between the experimental and model data using the Euclidean distance metric, to visualize the results, and to export them to Excel. The script replaces the need for manual comparison, thereby providing a faster and more systematic evaluation of model accuracy. The principle lies in determining the similarity score and subsequently filtering out irrelevant trajectories for validation. The algorithm is illustrated by the flowchart shown in

Figure 7.

All *.csv files located in the specified directory (path) are automatically loaded by the script. The files are classified into two categories: experimental data (identified by the keyword “experiment” in the filename) and model data. The data are subsequently stored in the dictionaries experiment_data and model_data.

After loading, the data are preprocessed to align the starting points of all trajectories. The initial segment of each model trajectory is trimmed using the start_position function (Equation (1)), which detected the onset of motion along the

Z-axis based on velocity in that direction. The function for finding the start of motion can be described as:

where

is threshold velocity determining the start of movement,

is average velocity in the

Z axis during the rest phase,

is sensitivity parameter (higher value → later detection) and

is standard deviation in the

Z axis during the rest phase.

Similarly, the end of each experimental trajectory could be trimmed when a decrease in motion along the Y axis was detected, according to user-defined parameters. All trajectory coordinates are then shifted so that they started at the origin, i.e., (x, y, z) = (0, 0, 0).

Firstly, since the number of data points for the experiment and the model may differ and they are not precisely time-synchronized, Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) is applied to address potential temporal misalignments between the trajectories. The general computation is expressed by the following Equation (2):

where

is total aligned distance between experiment and model,

is optimal matching of model–experiment index,

is number of samples after alignment,

is points (coordinates) of model and

is corresponding points (coordinates) of the experiment.

In the implementation, DTW was computed using the default dtw_ndim method from the dtaidistance Python library. The local cost function is based on the squared Euclidean distance in 3D, directly reflecting the coordinate differences between the trajectories. No global constraints were applied to the warping path (such as a Sakoe–Chiba window). The alignment follows only the standard DTW boundary, continuity, and monotonicity conditions defined by the default settings.

The main computational step is performed by calculating the Euclidean distance between trajectories. For each point in the experimental trajectory, the nearest corresponding point in the model trajectory was identified, and the distance between them is computed. For each experiment–model pair, the results are stored as either the average or total Euclidean distance. For each pair, the distance is determined according to the following Equation (3):

where

is distance between a pair of model and experiment points and

is

Z axis weight (higher value → higher weight).

In all results and procedures, a w value of 1 was used (with no effect). If it were necessary to give more weight to the forward displacement (Z axis), the w value would be set to >1. If more weight was given to the lateral and vertical displacement, the w value would be set to <1 (valid for positive numbers).

The models are subsequently ranked based on the similarity scores that were calculated (either the average or the total Euclidean distance). In general, the total distance can be used for comparison; however, when experiments with different trajectory lengths are compared, it is more appropriate to use the average distance. The calculation is defined by the following Equation (4):

where

is total deviation score and

is average deviation score.

The models that best fit each experiment are automatically selected, with the number of top-ranked models defined at the beginning of the script. The resulting similarity scores for all models are printed to the console for straightforward comparison. However, the total (summed) score is not suitable for evaluating model accuracy, as it depends on the trajectory length, measurement duration, and other experiment-specific factors, and is therefore used only for ranking. A more robust metric is the mean score, which represents the mean absolute error (MAE) of the 3D Euclidean distances between corresponding points of the experimental and simulated trajectories. Another metric commonly used to assess model accuracy is the root mean square error (RMSE), which places greater weight on larger deviations between the simulated and measured values. This error can be calculated using Equation (5):

where

is root mean square error.

For each experiment, two-dimensional plots were generated to visualize the trajectories of the best-performing models in the X–Z and Y–Z planes.

2.6. Development of the Simulation Model in Ansys Rocky

The simulation model of the laboratory soil channel was based on a simulation model with a material model of silica sand placed in an experimental soil bin, which was published in a previous study from 2024 [

26]. A 3D CAD model was created in Ansys SpaceClaim 24.1.1. In the original simulation model, a scaled-down tool geometry at a 1:2 ratio was applied. Since the real tool dimensions were used in this study, the dimensions of the soil channel were enlarged to 1000 × 2400 × 1020 mm. Although these dimensions did not fully correspond to the real laboratory channel, an active length of 1200 mm was defined, which was sufficient for tracking the motion of selected particles. The walls of the channel were simplified by representing them as surfaces. These modifications significantly reduced the computational time required for the simulation. The created 3D geometry models were exported and saved in *.stl format and subsequently imported into the Ansys Rocky 24.1.1 software. In the model, the tool depth was adjusted. While its real value was 184 mm, it was necessary to consider gravitational settling during the initial time steps. Therefore, the tool was shifted by −17 mm along the

Z-axis.

2.6.1. Particle and Boundary Configuration

The applied numerical models, material characteristics, and interaction parameters used in the simulation model are summarized in

Table 2. Contact behavior between particles was described using elastic and frictional contact formulations, while adhesion was neglected due to the dry condition of the simulated sand [

8].

Material parameters for both the sand and the tool were defined based on a combination of experimental measurements and literature sources. Bulk density of the particulate material was experimentally determined, whereas the mechanical properties of the steel tool and selected sand constants were obtained from literature sources. Particle material parameters regarding static and dynamic friction, Young’s modulus, and rolling resistance were refined using the DoE procedure. To increase computational efficiency, an enlarged particle size was applied within the simulated domain. The use of particles larger than the real grain size is referred to as coarse grain in DEM simulations and is considered an established approach that enables a reduction in the number of modelled particles while preserving the macroscopic behaviour of the material. Its applicability is supported for example by the study of Queteschiner et al. [

43], which demonstrates that larger representative particles can reliably substitute finer real particles when the corresponding contact and material parameters are appropriately adjusted. This approach reduces computational demands while maintaining sufficient accuracy at the scale relevant to the simulated processes. The possibility of using different particle sizes within a single model is further supported by the study of Pogulis and Servin [

44], where it is shown that finer particles may be applied in the contact region and coarser particles in the remaining parts of the domain. Such configurations exhibit shorter computational times and adequate accuracy in the prediction of surface interaction behaviour. Based on these findings, the particle domain in this study was constructed using two particle sizes. Finer particles with a diameter of 4 mm were placed in the upper layer that directly interacted with the tillage tool. Coarser particles with a diameter of 20 mm were used in the lower layer, where they served as a structural base. This layered configuration was selected to reduce the total number of particles in the model while maintaining the required level of accuracy in the regions where tool soil interaction occurred.

Table 2.

Material and boundary condition settings, including interaction models and physical parameters applied in the numerical simulation.

Table 2.

Material and boundary condition settings, including interaction models and physical parameters applied in the numerical simulation.

| Physics | Value | Source |

|---|

| Gravity in Y-direction | 9.81 m·s−2 | - |

| Normal Force Model | Hertzian Spring Dashpot | [45,46] |

| Tangential Force Model | Mindlin-Deresiewicz | [45,47,48] |

| Adhesive Force Model | None | [45] |

| Impact Energy | Default | [45] |

| Rolling Resistance Model | Type C: Linear Spring Rolling Limit | [45] |

| Material settings | Value | Source |

| Particles | | |

| Bulk Density | 1734 kg·m−3 | Experiment |

| Young’s Modulus | DoE | - |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.25 | [49,50] |

| Boundary | | |

| Density | 7800 kg·m−3 | [51] |

| Young’s Modulus | 210 GPa | [51] |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.30 | default |

| Materials Interactions | Value | Source |

| Particles × Particles | | |

| Static Friction | DoE | - |

| Dynamic Friction | DoE | - |

| Restitution Coefficient | 0.30 | default |

| Particles × Boundary | | |

| Static Friction | 0.40 | [51] |

| Dynamic Friction | 0.30 | [51] |

| Restitution Coefficient | 0.30 | default |

| Particles settings | | Source |

| Shape | Sphere | - |

| Material | Default Particles | - |

| Size | | |

| Particle 1 | 4 mm | - |

| Particle 2 | 20 mm | - |

| Rolling Resistance | DoE | - |

2.6.2. Model Validation Through Angle of Repose Measurements and DoE

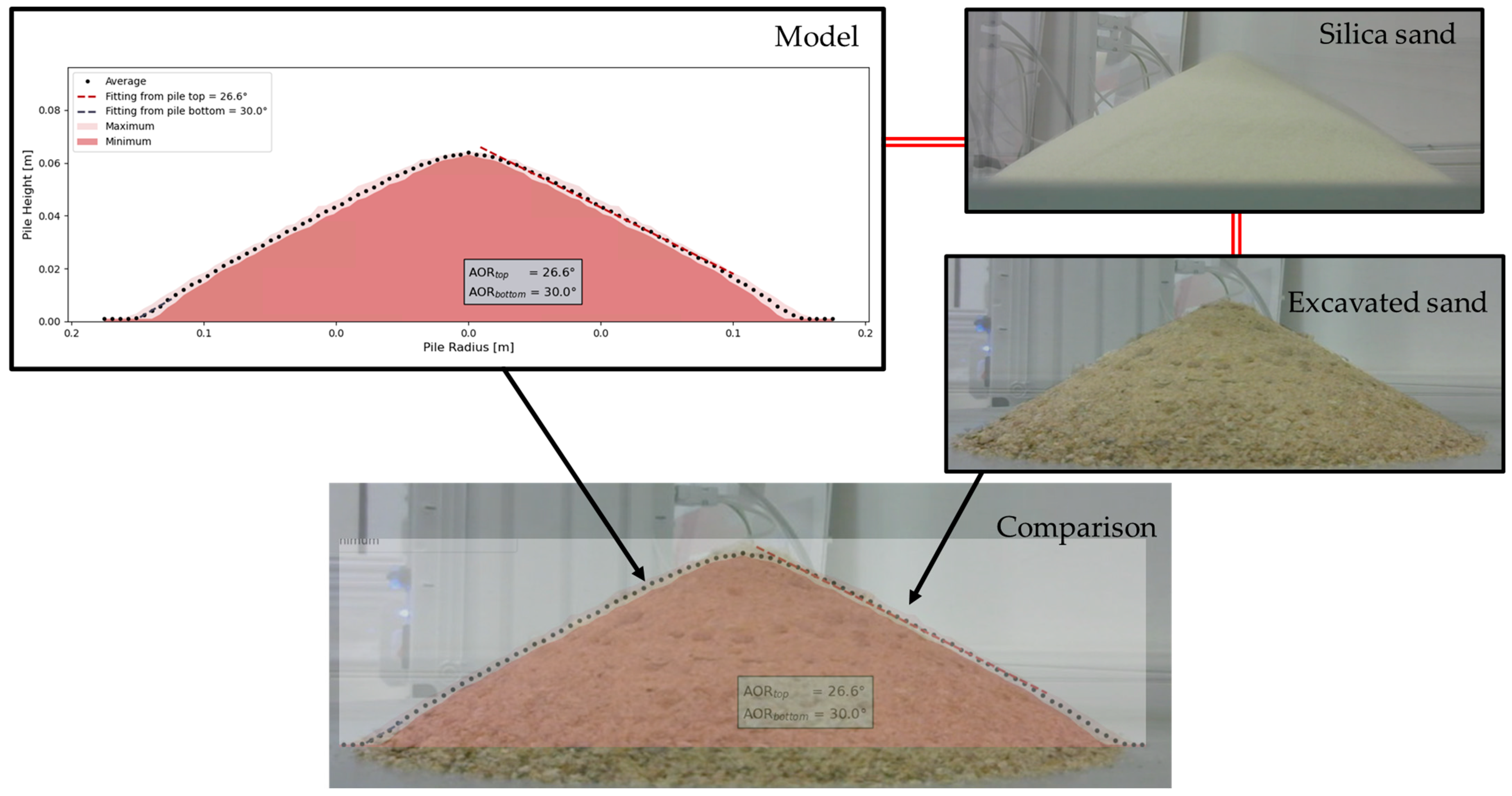

In order to verify our proposed validation methodology, it was first necessary to employ a previously validated DEM model. The validation of this reference model was performed using an experimental measurement of the angle of repose, followed by a DoE analysis to identify the most suitable combination of input parameters providing the closest match between the experimental and simulated results.

To determine the angle of repose for sand, a laboratory apparatus specifically constructed for this purpose was employed. The detailed experimental methodology is provided in Černilová et al. (2022) [

21], where an analogous procedure was applied to rapeseed. After the experiment, the geometry of the resulting sand pile was recorded using a camera. A DoE approach was then established, consisting of 30 individual simulation cases. For validation, a surrounding geometry model accurately representing the dimensions of the experimental device was employed [

21]. The simulation models followed the settings of the soil bin simulation model. The parameters varied within the DoE included the Young’s Modulus, Rolling Resistance, Dynamic friction and Static friction. The ranges for these parameters within the DoE are presented in

Table 3. Each model in the DoE was evaluated using a script provided by ESSS [

45], which is described in detail in Černilová et al. (2022) [

21].

3. Results

3.1. Camera Calibration—Intrinsic Camera Parameters

The intrinsic parameters obtained for both GoPro Hero 8 cameras are summarized in

Table 4. The table presents the root mean square error (RMSE), the intrinsic parameters, and the distortion coefficients

k1,

k2,

k3,

p1, and

p2. The tangential distortion coefficients (

p1,

p2) were found to be close to zero for both cameras, indicating negligible tangential distortion.

3.2. Camera Calibration—Extrinsic Camera Parameters

The point grid in space, created from the pixel coordinates obtained in Caliscope based on camera calibration, was subsequently used for ANN training. Prior to this, however, the suitability of the generated point grid for these purposes was verified by checking the distances of the reference points on the ChArUco board within the spatial coordinates. This verification was performed using the Euclidean distance, which represents an extension of the Pythagorean theorem into three dimensions. The equation was applied to calculate the distances between neighboring points, and it was found that the average distance between neighboring points was 40.43 mm (the actual spacing between neighboring points was 40.4 mm). The confidence interval for the given dataset, based on a significance level of α = 0.05, ranged from 38.38 to 42.42 mm. The mean value was therefore within this interval.

3.3. Obtaining X, Y, and Z Coordinates in Space Using an ANN

For the training and validation of the artificial neural network (ANN), a subset of 4149 samples was reserved from the total dataset of 94,939 records for independent testing. The performance of the trained model in predicting spatial coordinates was evaluated against the reference data, as summarized in

Table 5.

After training, the optimised ANN model was employed to reconstruct particle trajectories based on pixel inputs obtained from the Image Clicker application. Two datasets were provided to the model: one containing pixel coordinates from the front camera (xf and yf), and the other from the side camera (xs and ys). The resulting outputs, representing the predicted spatial coordinates (X, Y, Z), were automatically generated and exported as a *.csv file for subsequent analysis.

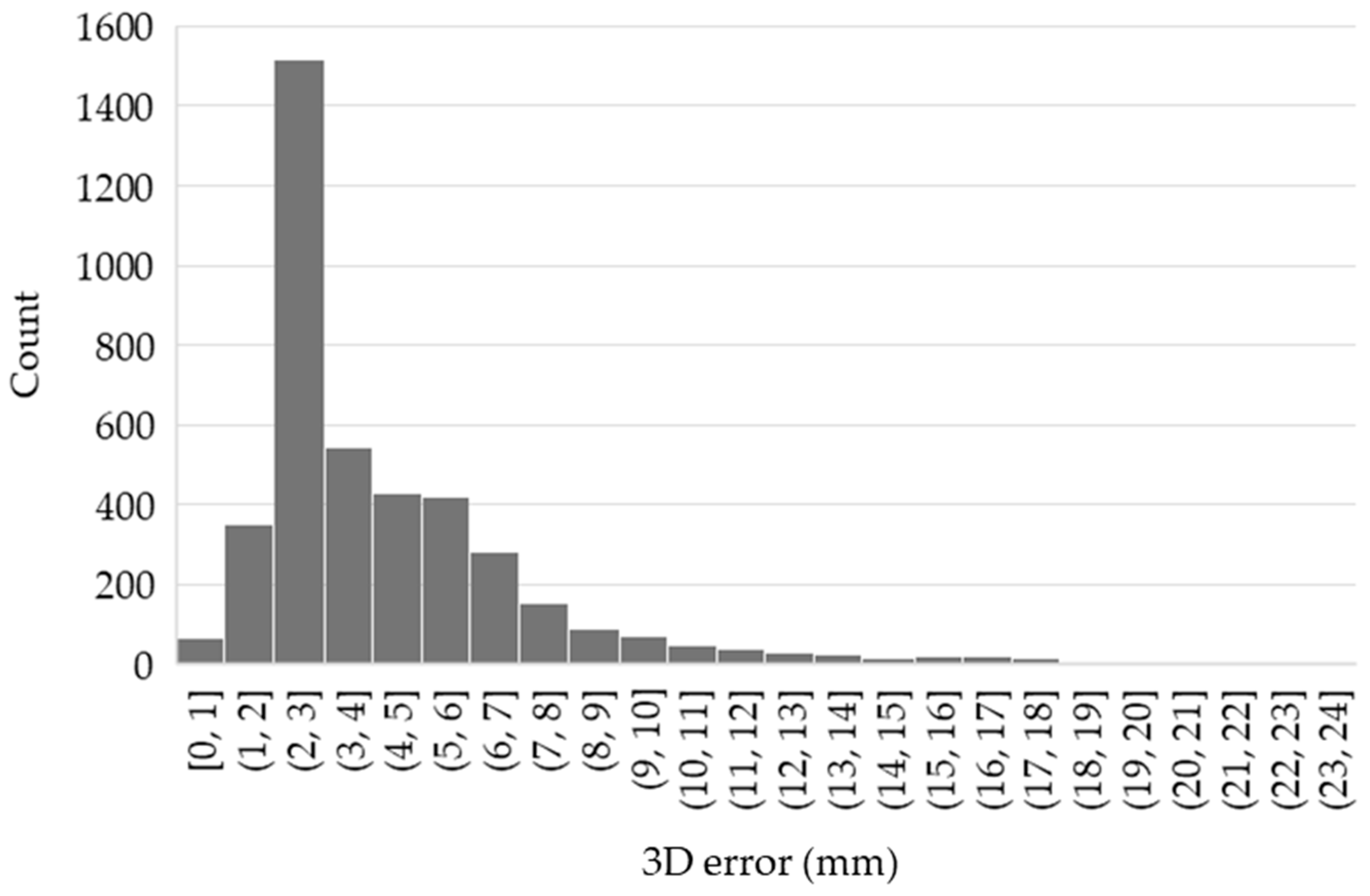

The average difference between the predicted and actual coordinates was 2.9 mm, with a standard deviation of 2.7 mm.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of the 3D position error of the ANN predictions in the form of a histogram. The error distribution is strongly right-skewed, with the vast majority of points reconstructed with high accuracy. The dominant peak is observed between 2 and 3 mm, where more than 1400 samples are concentrated. A gradual decrease in frequency is visible for errors in the range of 3–10 mm, indicating that moderate deviations occur less frequently. Only a small number of samples exceed 15 mm, and the maximum observed 3D error is approximately 23.9 mm. These larger deviations represent isolated outliers and are likely associated with regions situated near the edges of the calibration volume, where steeper viewing angles, increased perspective distortion and reduced overlap between the camera fields of view result in less favourable reconstruction conditions.

The mean difference of 40.04 ± 2.7 mm fell within the confidence interval of 38.38–42.42 mm established for the reference distance, corresponding to a relative deviation of approximately 6.6%. This is considered an acceptable deviation for the applied measurement method. The very high values of the coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9994 for the X-axis, 0.9993 for the Y-axis, and 0.9988 for the Z-axis) further confirm that the model predicts spatial coordinates very accurately and captures most of the variability in the data.

3.4. Model Validation Results—Angle of Repose Measurements

The material model was validated using the angle of repose test prior to the simulation. The average experimental angle of repose, measured from the base of the pile, was 30.82°, while the angle measured from the top of the pile was 26.42°. Within the DoE, the experimental results were compared with those obtained from a set of 30 model configurations. The best agreement was achieved with the model parameters listed in

Table 6. The DoE parameter configuration corresponded to that used for the silica sand model reported in a 2024 publication [

26]. However, the simulation setup itself differed in several aspects, including the material properties of the surrounding geometry, particle–geometry interaction parameters, motion frame configuration, bulk density, and other model-specific parameters.

Figure 9 presents a comparison between the experimental discharge results for excavated sand and silica sand and those obtained using a custom analysis script within the Ansys Rocky environment. For the selected model, the average angle of repose measured from the base of the pile was 30°, and 26.6° when measured from the top.

3.5. The Results of the Model

Two simulations were performed, one with a tool travel velocity of 1 m·s−1 and the other with a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s−1.

The simulation with a tool travel velocity of 1 m·s−1 required 92.4 GB of total memory and took 86 h, 39 min and 47 s to complete. For the simulation with a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s−1, the total memory requirement was 77.7 GB, and the computation time was 53 h, 38 min and 34 s. Both simulations included a total of 11,473,727 particles, 11,382,665 of which had a diameter of 4 mm and 91,062 of which had a diameter of 20 mm. The computational time step was set to 1 × 10−6 s and the data output interval to 0.01 s.

The total simulation time for a tool travel velocity of 1 m·s

−1 was 3 s, with actual tool motion starting at 1.5 s to allow for initial particle stabilisation under the effect of gravity. For the model with a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1, the total simulation time was reduced to 2.5 s due to the shorter time required for the faster tool passage.

Figure 10 presents an example of the simulation progress for the model with a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1 at time t = 2 s, where the particles are colour-coded according to their

Y-coordinate values. The figure also includes views from both cameras (labeled as Cam 1 and Cam 2), corresponding to the time step of 2 s in the simulation.

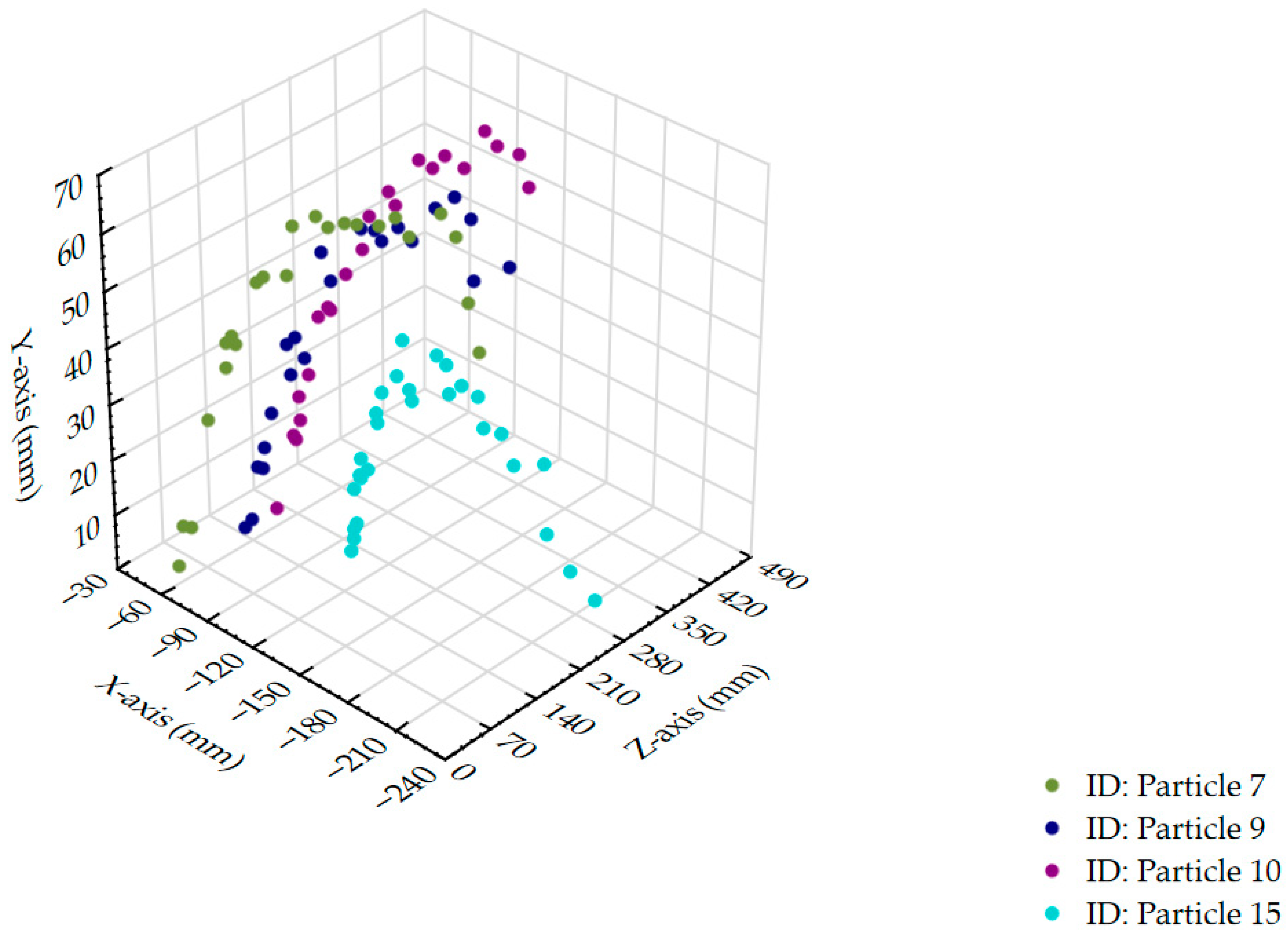

3.6. Reconstruction of Particle Trajectories from the Experiment

The accuracy of repeated clicking was determined to be ±2.36 pixels along the X-axis and ±2.75 pixels along the Y-axis. The number of frames in which individual particles could be tracked depended on the degree of occlusion by surrounding granular material as well as on the tool travel velocity. For the velocity of 1 m·s−1, an average of 22 ± 0.82 frames was used, whereas at 1.5 m·s−1 this number was 16.08 ± 2.47 frames.

Using the contrast particle tracking method at a tool travel velocity of 1 m·s

−1, particles 7, 9, 10, and 15 were clearly traced throughout their entire trajectories. The remaining particles were covered by an accumulated layer of particulate material, either without apparent entrainment by the surrounding medium or during the passage of the tool. Particles that were covered while being entrained could be at least partially tracked.

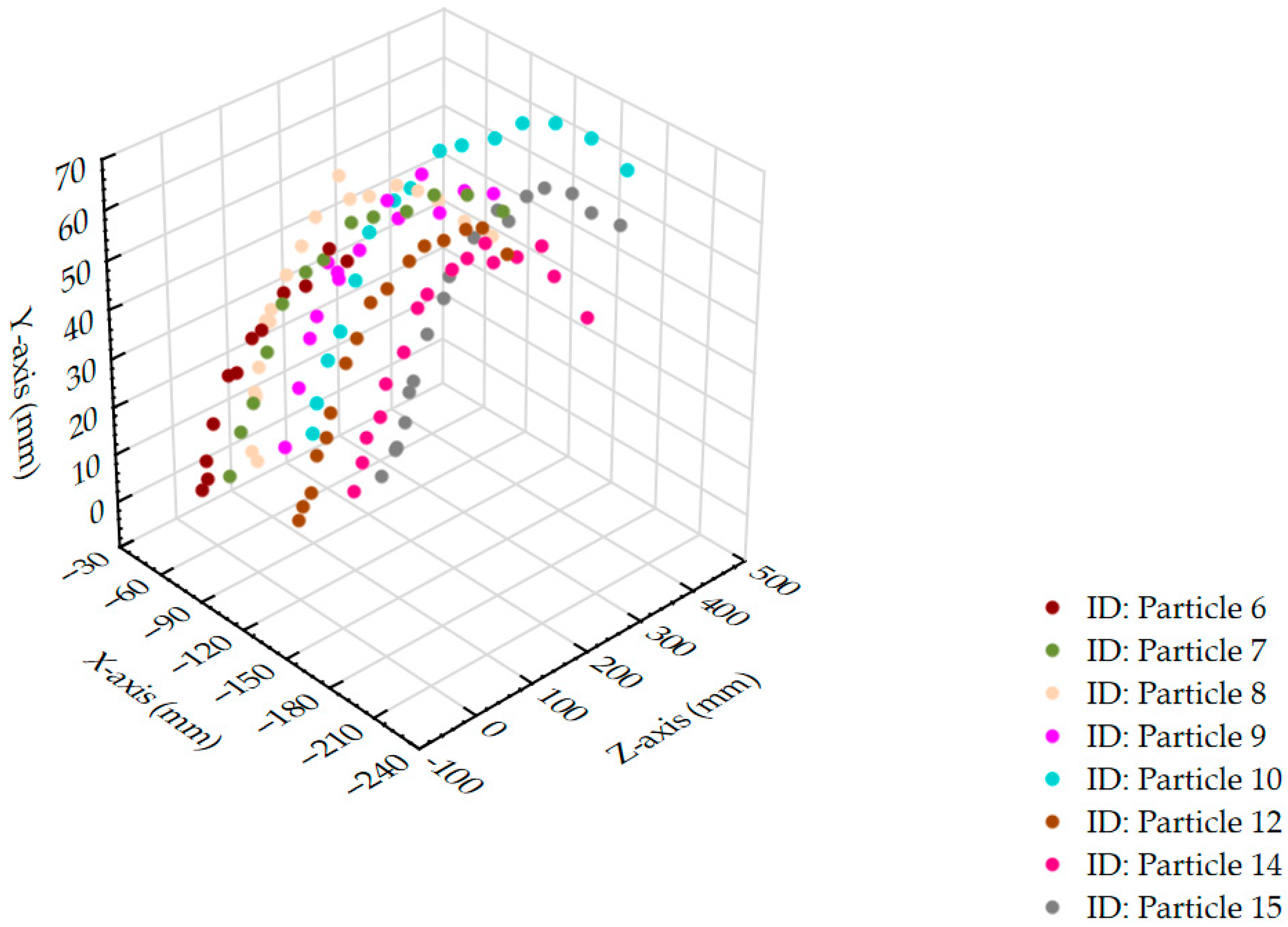

Figure 11 presents a 3D plot illustrating the trajectories of the fully tracked particles. The tool passage was oriented in the direction of the positive

Z-axis.

Using the contrast particle tracking method at a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1, particles 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, and 15 were clearly traced throughout their entire trajectories. The remaining particles, as in the case of the 1 m·s

−1 tool travel velocity, were covered by an accumulated layer of particulate material, either without apparent entrainment by the surrounding medium or during the tool passage.

Figure 12 presents a 3D plot illustrating the trajectories of the fully tracked particles.

3.7. Comparison of the Traces from the Experiment and the Model

Particle trajectories obtained from DEM simulation in the Ansys Rocky software were evaluated against those determined through image analysis. The correspondence between simulated and observed particles was determined based on their initial spatial coordinates. Each particle in the model possesses a unique identification number (Particle ID). The initial positions of the compared particles corresponded to the initial positions of the experimental particles.

To extract particle motion data (

X,

Y,

Z coordinates, timestep, and Particle ID) from Ansys Rocky within a predefined spatial domain, the Cube tool was utilised. The Cube tool generated particles from a region measuring 30 mm along the

X-axis, 20 mm along the

Y-axis, and 10 mm along the

Z-axis. This region was chosen to account for potential nuances in the initial positioning of particles in the experimental setup. In total, 90 particle trajectories were generated using the Cube tool. The algorithm, described in detail in

Section 2.5, automatically selected the relevant model trajectories, performed their comparison with the experimental data, and visualized the results.

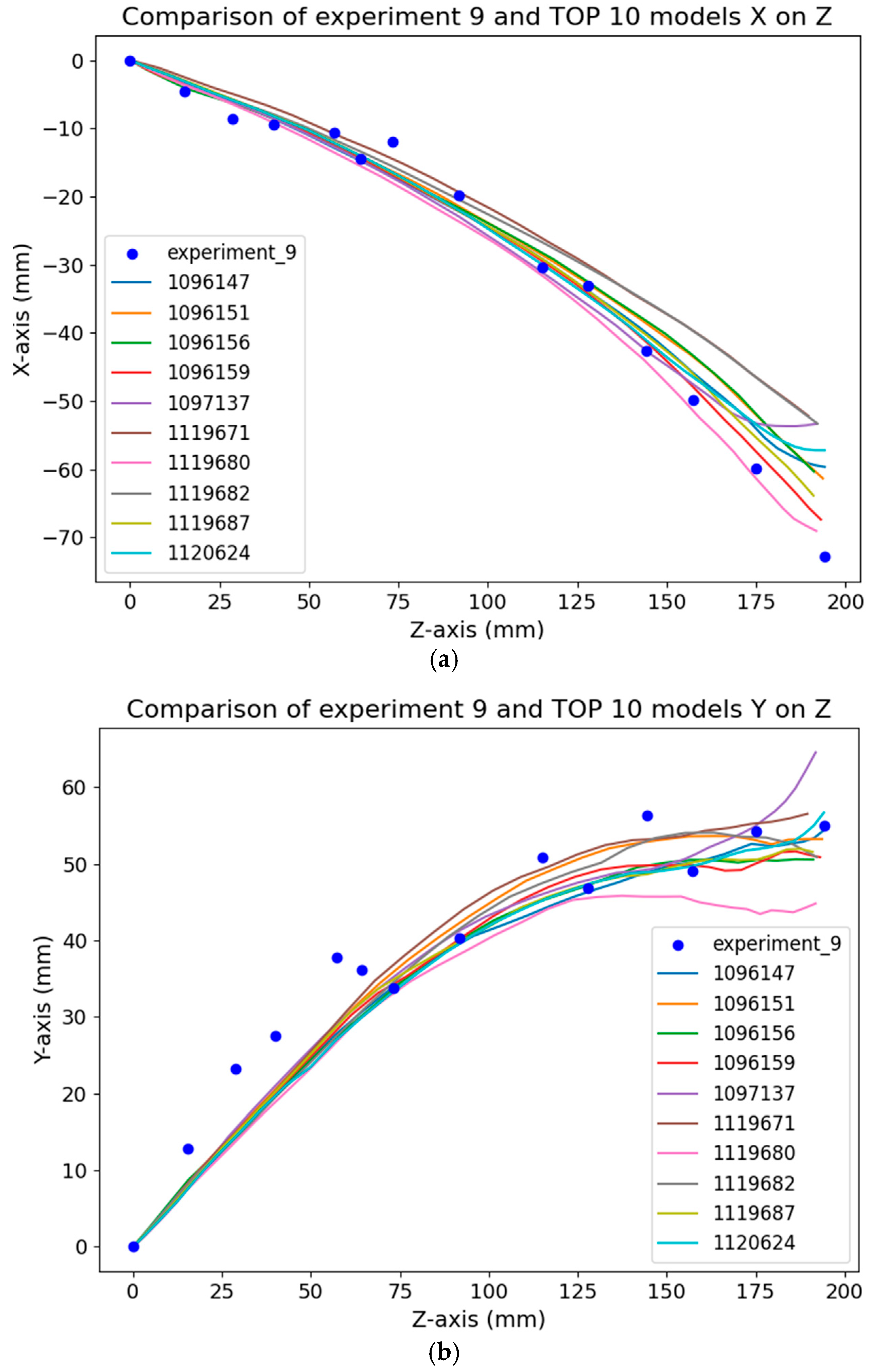

As illustrated in

Figure 13, experimental particle number 9 was compared with the corresponding model particles at a tool travel velocity of 1 m·s

−1 on the

X–

Z plane (a) and

Y–

Z plane (b). The graph was displayed up to the moment when slip occurred in the experimental particle. The plot includes a total of ten particles identified by the script as having the highest correspondence with the experimental trajectory. It is evident from the graph that the experimental trajectory exhibited a decreasing trend along the

X-axis, starting from approximately 0.13 m on the

Z-axis. In

Figure 13b, a good agreement between the experimental and model trajectories can be observed; however, the experimental data shows a slightly steeper trend. The maximum absolute deviation with respect to the

Z-axis was 0.0135 m at a z-position of 0.0793 m. In

Figure 14, experimental particle number 10 was compared with the corresponding model particles on the

X–

Z plane (a) and

Y–

Z plane (b). Again, the trajectory was displayed up to the point where slip occurred in the experimental particle. The plots clearly indicate an overall agreement between the experimental and model trajectories. For some model trajectories, an increasing trend from approximately 0.15 m was observed, which was likely caused by a stronger influence of the tool wings. The maximum absolute deviation with respect to the

Z-axis was 0.0092 m at a z-position of 0.0485 m. The highest agreement was achieved for particles with IDs 541240 and 557723.

In

Figure 15, experimental particle number 6 was compared with the corresponding model particles at a tool travel velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1 on the

X–

Z plane (a) and

Y–

Z plane (b). Similarly,

Figure 15 presents a comparison of experimental particle number 9 with the corresponding model particles under the same tool travel velocity conditions on the

X–

Z plane (a) and

Y–

Z plane (b). Each plot includes ten particles that were automatically identified by the analysis script as exhibiting the highest degree of correspondence with the experimental trajectory. The trajectories were displayed up to the point at which slip occurred in the experimental particles. For particle number 6, a steeper initial increase along the

X-axis was observed, as shown in

Figure 15a. This trend gradually converged with the model trajectories from approximately 0.06 m along the

Z-axis. The maximum absolute deviation with respect to the

Z-axis was 0.00728 m at a

Z-position of 0.027 m in the

X–

Z plane. As illustrated in

Figure 15b, a strong agreement between the experimental and model trajectories was observed in the

Y–

Z plane. In

Figure 16a, a similarly strong agreement between the experimental and model trajectories for particle number 9 is evident in the

Y–

Z plane. However, a slightly steeper increasing trend along the

Y-axis compared to the model can be seen in

Figure 16b, with the trajectories beginning to converge at approximately 0.075 m along the

Z-axis. The maximum absolute deviation with respect to the

Z-axis was 0.0087 m at a z-position of 0.057 m.

Table 7 presents the results obtained for the selected particles from the experiment. For each particle, the mean values of the error metrics calculated across all compared trajectories are reported, specifically the MAE, RMSE, the total trajectory range, and the normalised RMSE (nRMSE). The nRMSE represents the normalised RMSE, calculated as the ratio between the RMSE value and the total trajectory length, expressed in percentage. This provides a scale-independent metric that reflects the relative magnitude of the error in relation to the overall motion range. The results show that, for most analysed particles, the errors fall within a low to moderate range despite differences in trajectory length and geometry. Lower MAE and RMSE values are typically associated with longer and smoother trajectories, for which the model’s ability to follow the motion is more consistent. In contrast, higher deviations appear for shorter or geometrically less regular trajectories, which are more sensitive to local variations in direction or velocity. The nRMSE further indicates that the relative error remains at an acceptable level for most trajectories. For the tested tool travel velocities, the mean nRMSE reached 4.7% for 1 m·s

−1 and 9.41% for 1.5 m·s

−1, indicating that the relative error increases with higher tool travel velocity but remains within a reasonable range for both cases.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive and cost-effective methodology was developed for validating particulate material motion within DEM models under conditions corresponding to real field environments. The cost effectiveness here refers to the experimental part of the workflow, which uses affordable camera systems and open-source tools. The DEM simulations themselves are computationally intensive due to the high number of particles, but this does not affect the applicability of the measurement and trajectory tracking process. The proposed approach combined image analysis with an ANN to determine the spatial coordinates of particles based on pixel values obtained from two cameras and incorporated two custom-developed algorithms: the first one, Image Clicker, for rapid manual trajectory extraction, and the second, developed to process a large number of trajectories exported from Ansys Rocky. The Image Clicker algorithm enables rapid manual extraction of particle trajectories from individual image frames without requiring high computational resources. This approach eliminates the need for high-speed cameras, as the method can be effectively applied even with standard recording devices featuring lower frame rates, such as the GoPro camera used in this study. Its advantage lies in the ability to accurately reconstruct the motion of selected particles from conventional video footage, making the process both time-efficient and accessible for experimental validation without the necessity of specialized imaging equipment. However, it is important to note that manual particle tracking may introduce certain limitations, particularly when large numbers of trajectories or longer recordings are required. In this study, the trajectories could be annotated relatively quickly due to the limited number of frames, and the method proved highly effective and flexible for experimental validation. Although the procedure is inherently repetitive and may be susceptible to fatigue-related or operator-dependent variations, such potential variability is considered acceptable given the simplicity and accessibility of the approach. In the conducted evaluation, repeated annotation of the same particle showed a variability of approximately ±2.36 pixels along the X-axis and ±2.75 pixels along the Y-axis. The latter algorithm is primarily responsible for the processing, refinement and systematic selection of trajectory data, automatically identifying and excluding trajectories that do not correspond to the experimental results. It subsequently performs the comparison between the experimental and simulated datasets and generates a visualization of the validated trajectories. Although the DEM simulations are computationally intensive due to the high particle count, this level of detail provides the accuracy needed for a reliable comparison with experimental trajectories. Future work may benefit from using a reduced particle resolution, a smaller simulation domain, or more powerful hardware to improve computational efficiency while keeping the simulation results reliable. Future work may also explore the use of automatic particle detection methods, such as conventional computer-vision techniques or deep-learning-based approaches, to further streamline the acquisition of experimental trajectories. While these methods could substantially reduce manual effort and enable processing of larger datasets, their implementation may introduce new challenges, including the need for annotated training data, increased computational demands, and the risk of reduced robustness under varying lighting conditions.

This study builds upon our previous research [

26], which focused on validating particle motion within a laboratory soil bin filled with silica sand and containing a scaled model of an agricultural tool. The present work brings the applicability of the previously proposed methodology to field-like conditions, characterized by operational velocities representative of real tillage processes and by the use of a full-scale tool. In contrast to the previous study, higher tool velocities were analyzed (1.0 and 1.5 m·s

−1, compared to 0.1 m·s

−1 previously), made possible by the Image Clicker algorithm. Furthermore, instead of silica sand, a natural excavated sand was used, whose more heterogeneous composition better represents the behavior of complex particulate systems typical of a real agricultural environment. Achieving this required several methodological innovations, including a redesigned tracking workflow, a new ANN trained on a calibration dataset one order of magnitude larger, and an experimental protocol adapted for the dynamic behavior of heterogeneous excavated sand. These developments address the key limitation of the previous methodology and enable accurate trajectory determination under field like kinematic and geometric conditions. As a result, the proposed approach represents a significant advancement, making ANN-based trajectory reconstruction applicable to real scale tillage processes for the first time.

More comprehensive validation frameworks, such as the approach of Pásthy et al. [

12], include among others a technique designed for monitoring subsurface particle motion. Such complex, multi-level validation strategies represent an important contribution to the development of robust and broadly applicable DEM models. Nevertheless, given the complex nature of particulate behaviour, it is also necessary to analyse the dynamics of the material at the surface, because particles in granular systems often exhibit different motion patterns at the free surface compared to those embedded in the bulk [

23]. In this context, the method presented in this paper can serve as a complementary and accessible component of such a validation framework. Still, the implementation of such complex methodology can be demanding in terms of time and computational performance and may exceed the requirements of a specific intended use [

15]. The validation method presented in this paper can serve as a complementary component within complex DEM validation frameworks or it can be used independently for surface-based evaluation of particle motion. The fact that the current approach does not include direct subsurface tracking represents a limitation, though not a critical one for its intended use. Surface dynamics represent a distinct and often more responsive component of particulate behaviour, as particles at the free surface experience fewer constraints and therefore show clearer changes in velocity and direction during tool interaction [

23,

52,

53]. While surface motion does not capture the full complexity of bulk behaviour, it provides a sensitive and practically accessible indicator for assessing whether the model reproduces the key observable features of the process [

52,

53].

A major limitation of traditional DEM model verification lies in its confinement to laboratory conditions, where the preservation of true field parameters, such as natural particulate matter structure and realistic tool operating velocities, is not feasible [

17,

29]. Moreover, laboratory testing often involves handling and transport of particulate samples, which can cause degradation and alter their mechanical properties [

30]. In contrast, the experimental setup employed in this study was designed to replicate field-like conditions, using a real agricultural tool operating at velocities of 1 m·s

−1 and 1.5 m·s

−1, corresponding to typical medium-depth tillage tool operating velocities. The proposed methodology therefore bridged the gap between laboratory validation and real-world testing, yielding results that were both representative and reproducible. With minor modifications, such as mounting the camera system directly onto agricultural implements, this methodology could be applied directly during field operations. However, applying the method in real field conditions introduces several practical challenges that were not present in the controlled laboratory environment. These include vibration of the machinery resulting in camera vibrations (currently none observed due to rigid mounting), variable and rapidly changing lighting conditions, dust or soil accumulation on the camera lens, occlusion of tracked particles, and limitations in stable camera mounting positions. Addressing these factors would be necessary to ensure reliable image capture and trajectory reconstruction during actual field operations. With respect to broader applicability, the methodology is not limited to dry (or near-dry) sand. Because the image-based reconstruction and trajectory comparison framework is material agnostic, it can be adapted to other granular systems, including moist soils, non-spherical particles and media with wide particle size distributions. In such cases, the DEM material parameters and, if needed, the tracking markers or imaging conditions must be adjusted, while the proposed validation workflow comprising calibration, ANN-based reconstruction and trajectory matching remains directly applicable. The presented method therefore provides a generalizable foundation for validating DEM models across a wide range of granular materials and supports future development of in situ verification techniques in agricultural practice.

Compared with conventional stereoscopic reconstruction, which requires strict geometric assumptions and precise point matching, the ANN-based approach can directly learn the nonlinear pixel-to-space relationships from calibration data. This makes the method more tolerant to lens distortion, imperfect synchronisation, and partial occlusions, improving reconstruction accuracy under non-ideal experimental conditions. The selected configuration (2048–1024–512 neurons) was identified through a DoE analysis as the architecture that provided the highest accuracy among the tested models. Although the adopted architecture was wider than commonly used MLPs, this design proved advantageous due to the highly nonlinear nature of the pixel-to-space mapping and the large amount of available training data. Potential overfitting was mitigated by applying dropout regularisation (0.2 after each hidden layer), early stopping based on validation loss and data normalisation, all of which ensured stable generalisation of the model. The model achieved high accuracy, with R2 values of 0.9994, 0.9993, and 0.9988 for the X-, Y-, and Z-axes and an average deviation of 2.7 mm, confirming its suitability for trajectory reconstruction.

The comparative analysis of the experimental and simulated trajectories confirmed strong agreement between the DEM model and real particle motion. The discrepancies observed at the trajectory edges can be attributed to several factors. First, the larger size and distinct material properties of the contrast particles may have influenced their behavior during the interaction, potentially causing deviations from the motion of the surrounding granular material. These particles may, for example, have been more prone to localized protrusion above the surface, exhibited different motion dynamics, or differed in their settling behavior, which could have contributed to minor discontinuities or variability in the experimentally recorded trajectories. Second, manual particle selection introduced small but systematic variations in pixel localization, which propagated into the reconstructed spatial coordinates. Third, differences may arise from local variations in the real material structure that cannot be fully reproduced in the numerical model, even when global material parameters are well calibrated. Fourth, partial occlusions of contrast particles by surrounding granular material could limit the continuity of the experimental tracks, particularly near regions of rapid surface deformation. However, a perfect match between experimental and simulated trajectories is not expected, because granular systems exhibit inherently stochastic behaviour that depends on local particle configurations, microscopic contact variations and small perturbations that cannot be fully reproduced in a numerical model. Partial deviations therefore represent a natural outcome of dynamic particulate motion rather than a methodological limitation.

Despite these nuances, the overall consistency between measured and simulated particle motion validates the proposed framework. At the same time, the results demonstrate that trajectory-based evaluation provides a more sensitive verification criterion than static tests such as the angle of repose. The observed deviations may therefore serve as an indicator of whether additional refinement of DEM parameters is required. This highlights that relying solely on static calibration methods is insufficient for assessing the dynamic behaviour of particulate materials. The presented methodology thus not only enhances the accuracy and relevance of DEM model validation but also establishes a foundation for future development of in situ verification techniques directly applicable in agricultural practice.

The key findings of this study are as follows:

The neural network analysis exhibited a very high degree of accuracy, achieving R2 values of 0.9994, 0.9993, and 0.9988 for the X, Y, and Z-axes, respectively. The standard deviation between predicted and actual coordinates was found to be 2.7 mm;

A comparison of the particle trajectories derived from the model and those obtained from the experiment revealed a strong agreement;

The proposed methodology enables precise trajectory determination and provides a reliable framework for the validation and calibration of DEM-based models in a laboratory soil channel with field-representative geometry and operating velocities, with potential applicability in real field conditions.