Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: A Scoping Review of Disruptive Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

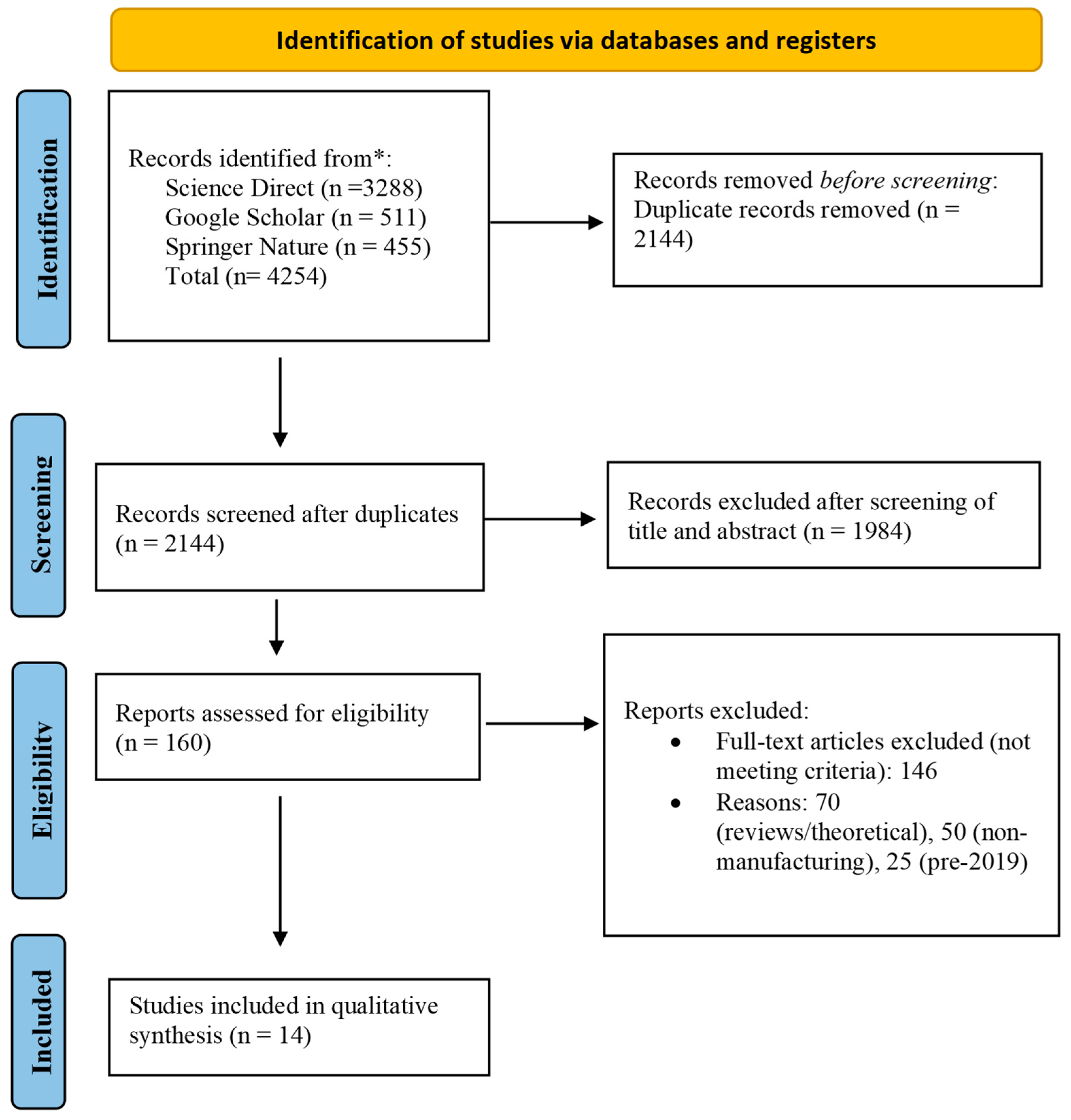

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Objectives

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Management

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Mapping

| Study | MMAT Score (%) | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | 90 | Robust experimental design | Limited variance reporting |

| [14] | 85 | Clear methodology, real-world data | High variability in outcomes |

| [17] | 80 | Practical implementation | Unspecified sample size |

| [18] | 75 | Innovative approach (preprint) | Lack of peer review validation |

| [19] | 90 | High accuracy metrics | Small dataset (n = 22) |

| [20] | 82 | Real-world testing | Limited generalizability |

| [21] | 92 | Comprehensive validation | Complex methodology |

| [22] | 87 | Optimized experimental design | Qualitative focus |

| [23] | 70 | Real-world case study | Lack of quantitative data |

| [24] | 85 | VR integration | Robot-specific focus |

| [25] | 78 | Simulation robustness | No real-world validation |

| [9] | 95 | Rigorous data collection | High computational demand |

| [15] | 75 | Novel trust framework | Simulation-only |

| [26] | 88 | Edge computing application | Limited sample diversity |

| Authors | Objective | Technology | Study Design | Key Metrics | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Develop an IoT-based CTMS for line balancing | IoT (IR sensors, LabVIEW, cloud database) | Experimental simulation, 5 samples | Cycle time, downtime, std. dev. | 0.44–1.71% faster, std. dev. 0.16–1.32 |

| [14] | Develop an IoT and ML system for maintenance | IoT sensors, AdaBoost ML | Experimental, 60/20/20 split | Event duration, 92% accuracy | 92% accuracy, mean = 84.55 s, std. = 3666.01 |

| [17] | Design an IIoT-based monitoring system | IIoT (wireless sensors, radio-frequency identification RFID) | System design, real-time evaluation | Cycle time, unqualified times | 0.08–20.20 s, 0–486 unqualified times |

| [18] | Devise a CTP mechanism for flow scheduling | IIoT, CSQF, CTP | Theoretical model, 1000–4000 flows | Latency, flow percentage | +31.2% flows, 94.45% Tabu FO-CS |

| [19] | Optimize robotic cycle time with TSP | Robotics (Adept Viper s650), MATLAB | Theoretical, 5 tests | Cycle time, cost reduction | 9% reduction, 7.38% mean reduction |

| [20] | Use big data analytics in IoT robotics | IoT, Decision Tree, Bagging, SVC | Mixed methods, 22 measurements | Classifier accuracy | 97% accuracy (Decision Tree) |

| [21] | Optimize ALB with cobots | Collaborative robots | Theoretical, case study | Cost efficiency, ergonomics | Cost-efficient, improved ergonomics |

| [22] | Develop a DT for robot programming | Digital Twin, VR (HTC Vive), Unity | Simulation, real-world test | Latency, joint error | 40 ms, −0.3 to 0.3° error |

| [23] | Predict quality with edge computing | Edge computing, SMOTE-XGBoost | Experimental, 1844 samples | Area Under the Curve (AUC), R2 | AUC 0.916, R2 > SVM, LR, DT, RF |

| [24] | Develop R3 M for robot reconfiguration | Robotics (ABB IRB-1200), ROS2, MoveIt!2 | Simulation, real-world use case | Positional error, orientation error | 0.0080–0.0211 m, 0.0138–1.6401 radians |

| [25] | Develop an IoT-controlled robotic arm | IoT (NodeMCU), 3 DOF arm | Simulation, real world | Angular variation | 3% variation, successful pick-and-place |

| [9] | Develop a DT framework for HRC safety | Digital Twin, faster R-CNN, UR10 | Simulation, real world testing | mAP, detection speed | mAP 0.605–0.789, 20–100 fps |

| [15] | Develop an IoT platform for navigation | IoT server, IALO-SVR, CNN | Real-time testing | RMSE, MAPE, accuracy | RMSE 1.48–2.63 cm, 97.14–99.42% accuracy |

| [26] | Develop a DT-driven trust framework for HRC | Digital Twins, APF, sensors | Simulation case study | Trust dynamics, path efficiency | Improved trust, qualitative efficiency |

3. Results

3.1. IoT-Driven Manufacturing Optimization

3.2. Robotics and Human–Robot Collaboration (HRC)

3.3. Emerging Technologies Enhancing IoT and Robotics Integration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| DTs | Digital Twins |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| HRC | Human–Robot Collaboration |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MMAT | Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CTMS | Collaborative Task Management System |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| CSQF | Context-Sensitive Queuing Framework |

| CTP | Cycle Time Prediction |

| FO-CS | Flow-Oriented Control Strategy |

| TSP | Traveling Salesman Problem |

| ALB | Assembly Line Balancing |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| ROS2 | Robot Operating System 2 |

| MoveIt!2 | A motion planning framework, second version |

| 3DOF | Three Degrees of Freedom |

| NodeMCU | Microcontroller unit |

| SMOTE-XGBoost | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique–eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| RF | Random Forest |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| AP50 | Average Precision at 50% Intersection over Union |

| IALO-SVR | Improved Adaptive Learning Optimization–Support Vector Regression |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| APF | Artificial Potential Field |

| R3M | Robot Reconfiguration and Motion Management |

References

- Rezazadeh, J.; Ameri Sianaki, O.; Farahbakhsh, R. Machine Learning for IoT Applications and Digital Twins. Sensors 2024, 24, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.I.-K.; Huang, H.; Xu, X. Digital Twin-driven smart manufacturing: Connotation, reference model, applications and research issues. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 61, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sui, F. Digital twin-driven product design, manufacturing and service with big data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet of Things—Worldwide. Statista Market Forecast. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/tmo/internet-of-things/worldwide (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Nangia, S.; Makkar, S.; Hassan, R. IoT based Predictive Maintenance in Manufacturing Sector. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing & Communications (ICICC) 2020, Delhi, India, 21–23 February 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, G.; Noens, R.; Nica, W.; Accoto, D.; Juwet, M. Advancing Human-Robot Collaboration: A Focus on Speed and Separation Monitoring. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerging Technologies: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/industries/high-tech/topics/emerging-tech-trends (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Chulakit, S.; Sadun, A.S.; Jalaludin, N.A.; Jalani, J.; Ahmad, S.; Hanapi, M.H.M.; Sabarudin, N.A. A Centralized IOT-Based Process Cycle Time Monitoring System for Line Balancing Study. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Mech. 2023, 105, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Law, J.; Calinescu, R.; Mihaylova, L. A deep learning-enhanced Digital Twin framework for improving safety and reliability in human–robot collaborative manufacturing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 85, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, V.; Pini, F.; Leali, F.; Secchi, C. Survey on human–robot collaboration in industrial settings: Safety, intuitive interfaces and applications. Mechatronics 2018, 55, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, M.; Maturana, F.P.; Barton, K.; Tilbury, D.M. Real-Time Manufacturing Machine and System Performance Monitoring Using Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Automat. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkateb, S.; Métwalli, A.; Shendy, A.; Abu-Elanien, A.E.B. Machine learning and IoT—Based predictive maintenance approach for industrial applications. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 88, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, E.; Lin, W.; Yang, S.X.; Yang, S. A novel digital twins-driven mutual trust framework for human–robot collaborations. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Intelligent manufacturing production line data monitoring system for industrial internet of things. Comput. Commun. 2020, 151, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Yu, F.R. CSQF-based Time-Sensitive Flow Scheduling in Long-distance Industrial IoT Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.09585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwa, A.; Iftikhar, A.; Afsheen, R.; Mujtaba, H.; Khan, M.F. Use of Big Data in IoT-Enabled Robotics Manufacturing for Process Optimization. J. Comput. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 7, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareemullah, H.; Najumnissa, D.; Shajahan, M.S.M.; Abhineshjayram, M.; Mohan, V.; Sheerin, S.A. Robotic Arm controlled using IoT application. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 105, 108539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroulanandam, V.V.; Satyam; Sherubha, P.; Lalitha, K.; Hymavathi, J.; Thiagarajan, R. Sensor data fusion for optimal robotic navigation using regression based on an IOT system. Meas. Sens. 2022, 24, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottin, M.; Boschetti, G.; Rosati, G. Optimizing Cycle Time of Industrial Robotic Tasks with Multiple Feasible Configurations at the Working Points. Robotics 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckenborg, C.; Spengler, T.S. Assembly Line Balancing with Collaborative Robots under consideration of Ergonomics: A cost-oriented approach. IFAC-Pap. 2019, 52, 1860–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, G.; Kuts, V.; Anbarjafari, G. Digital Twin for FANUC Robots: Industrial Robot Programming and Simulation Using Virtual Reality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, S.; Bueno, M.; Ferreira, P.; Anandan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Ragunathan, G.; Tinkler, L.; Sotoodeh-Bahraini, M.; Lohse, N.; et al. Rapid and automated configuration of robot manufacturing cells. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wei, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, K. Edge computing-based proactive control method for industrial product manufacturing quality prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.; Haider, M. Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G.; Sommerville, I. Socio-technical systems: From design methods to systems engineering. Interact. Comput. 2011, 23, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Ueshiba, T.; Tada, M.; Toda, H.; Endo, Y.; Domae, Y.; Nakabo, Y.; Mori, T.; Suita, K. Digital Twin-Driven Human Robot Collaboration Using a Digital Human. Sensors 2021, 21, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ye, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, A.; Deng, G.; Liao, T.; Sun, J. CNNs based Foothold Selection for Energy-Efficient Quadruped Locomotion over Rough Terrains. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Dali, China, 6–8 December 2019; pp. 1115–1120. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Keyword Search | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Science Direct | Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: Disruptive Technologies | 3288 |

| Google Scholar | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((IoT OR Internet of Things”) AND (robot* OR “industrial robot*”) AND (manufactur* OR “smart factory”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2018 | 511 |

| Springer Nature | Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: Disruptive Technologies | 445 |

| Study | Key Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|

| [8] | Cycle time improvement | 0.44–1.71% |

| Standard deviation | 0.16–1.32 s | |

| Correlation | 0.9465–0.9997 | |

| [14] | Accuracy | 92% |

| Event duration (mean, SD) | 84.55 s, 3666.01 s | |

| [26] | Online cycle time | 0.08–20.20 s |

| Unqualified times | 0–486 instances | |

| [18] | Schedulable flows (FO-CS, Tabu) | 31.2%, 94.45% |

| Packet delay | ~120 µs | |

| [19] | Classifier accuracy (DT) | 97% |

| [20] | Angular movement variation | 3% |

| [21] | Learning accuracy | 0.98 |

| RMSE | 1.48–2.63 cm | |

| MAPE | 1.72–3.54% | |

| Accuracy improvement | 2% (97% to 99%) |

| Study | Key Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|

| [22] | Cycle time reduction | 9% (mean: 7.38%) |

| [24] | Latency | 40 ms |

| Joint movement error | −0.3 to 0.3° | |

| [25] | Positional error (3D) | 0.0080–0.0211 m |

| Orientation error | 0.0138–1.6401 radians | |

| [9] | mAP | 0.605–0.789 |

| AP50 | 0.844–0.993 | |

| Detection speed | 20–100 fps | |

| [15] | Trust dynamics | Improved (qualitative) |

| Study | Technology | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| [24] | Digital Twin, VR | Latency: 40 ms, Error: −0.3 to 0.3° |

| [19] | Big Data Analytics | Accuracy: 97% |

| [26] | Edge Computing, SMOTE-XGBoost | AUC: 0.916, Higher R2 |

| [9] | Digital Twin, Deep Learning | mAP: 0.605–0.789 |

| [21] | IALO-SVR, CNN | Accuracy: 0.98 |

| [15] | Digital Twins | Improved trust (qualitative) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salawu, G.; Glen, B. Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: A Scoping Review of Disruptive Technologies. Technologies 2025, 13, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120566

Salawu G, Glen B. Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: A Scoping Review of Disruptive Technologies. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):566. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120566

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalawu, Ganiyat, and Bright Glen. 2025. "Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: A Scoping Review of Disruptive Technologies" Technologies 13, no. 12: 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120566

APA StyleSalawu, G., & Glen, B. (2025). Exploring the Integration of IoT and Robotics in Manufacturing: A Scoping Review of Disruptive Technologies. Technologies, 13(12), 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120566