XRD Characterization of Activated Carbons Synthesized from Tyre Pyrolysis Char via KOH Activation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Carbon Material from Pyrolysis Process

3. Experimental Processes

3.1. Raw Material

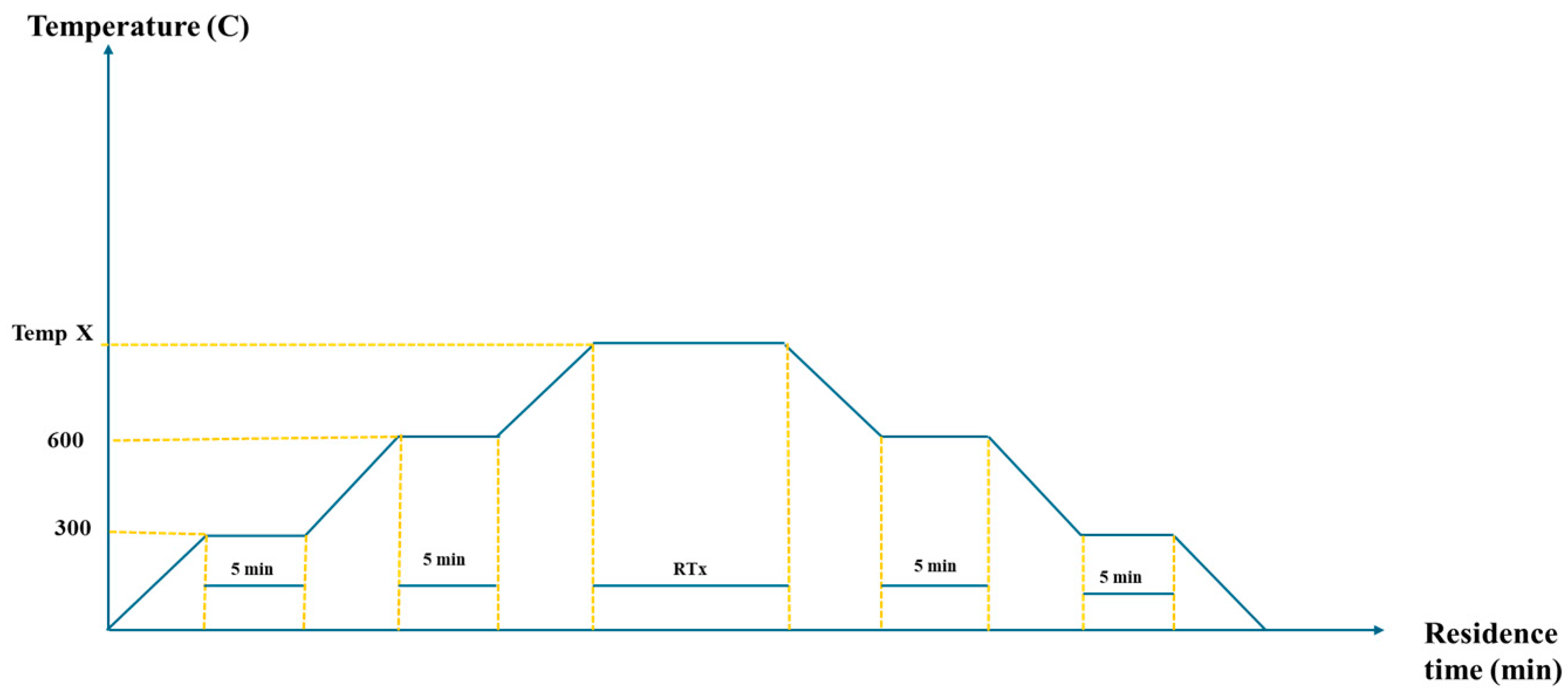

3.2. Activation

3.3. Crystal Structure Analysis of Activated Carbon

4. Results and Discussion

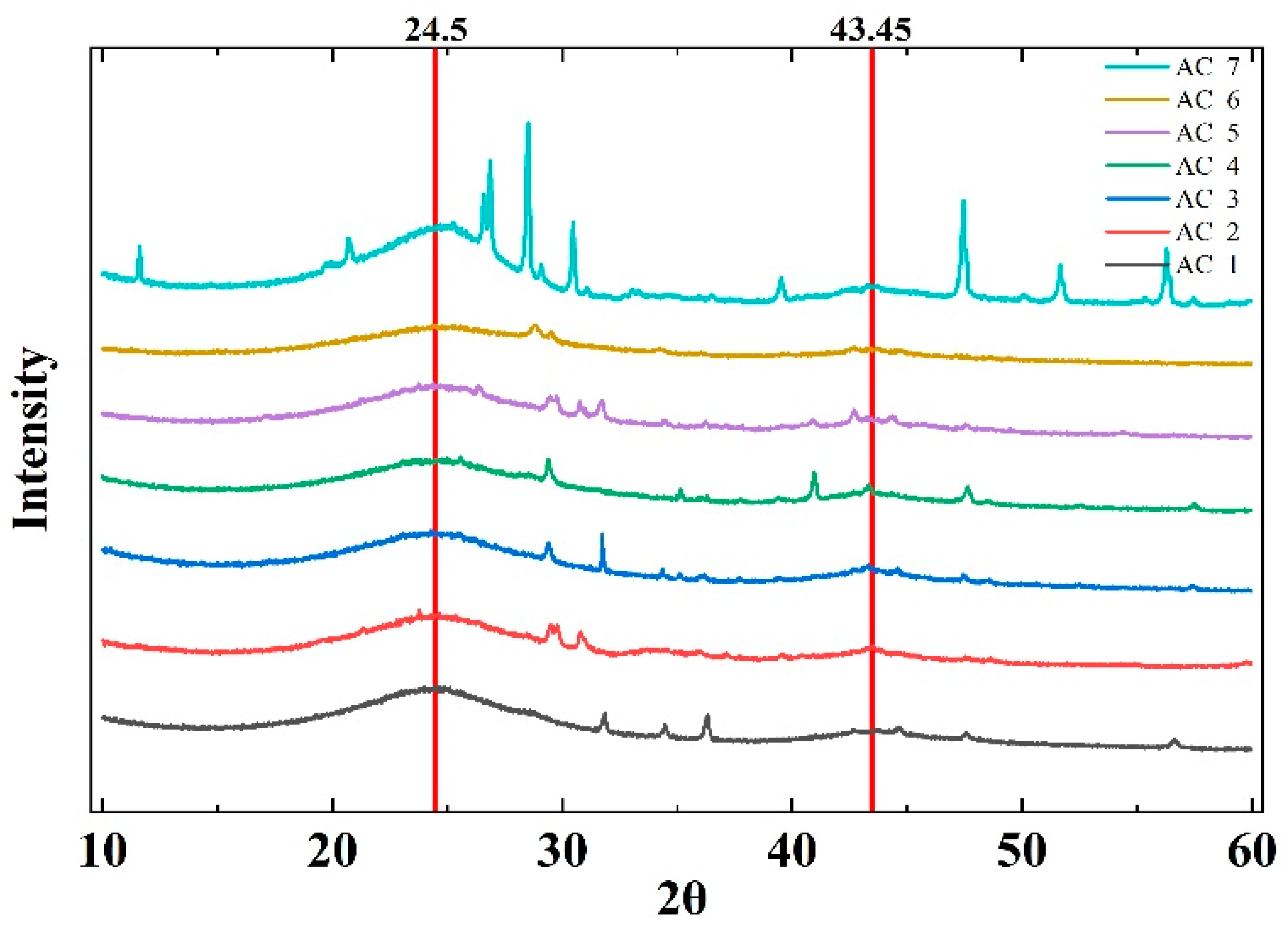

4.1. Shape of XRD Diffraction Pick

4.2. Interplanar Distance and Crystal Size of Raw Carbon Black

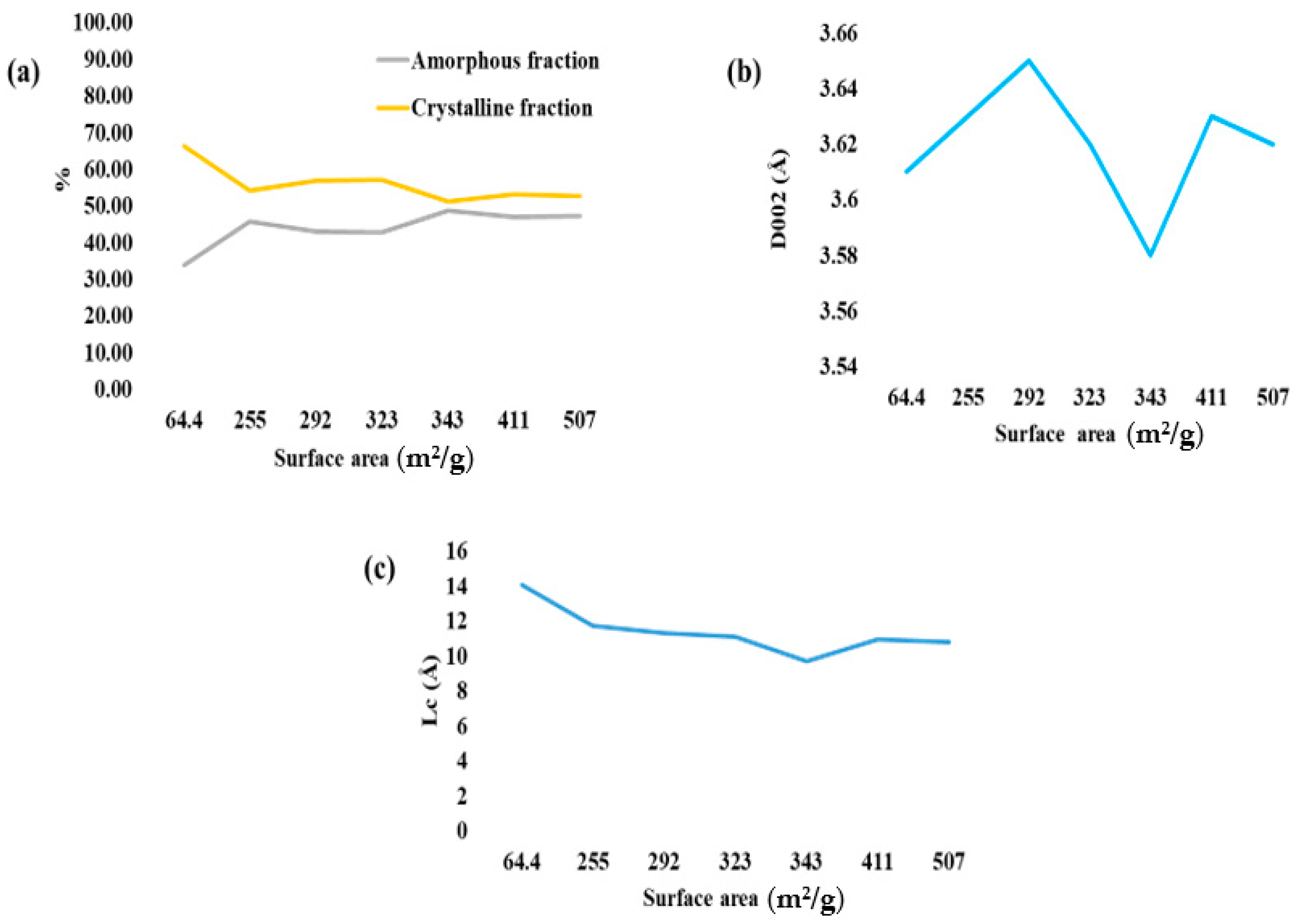

4.3. Effects of Activation Process on Structural Parameters of the Material

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Lc | crystallite size |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| TDAC | tyre-derived activated carbon |

| ACs | activated carbons |

References

- Stein, I.Y.; Constable, A.J.; Morales-Medina, N.; Sackier, C.V.; Devoe, M.E.; Vincent, H.M.; Wardle, B.L. Structure-mechanical property relations of non-graphitizing pyrolytic carbon synthesized at low temperatures. Carbon 2017, 117, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.E. Crystallite growth in graphitizing and non-graphitizing carbons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1951, 209, 196–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach, D.B. The graphitization process. Tanso 1971, 1970, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, E.S.; Mensah-Darkwa, K.; Agyemang, F.O.; Agbo, P.; Nashiru, M.N.; Andrews, A.; Adom-Asamoah, M. Performance evaluation of waste tyre-activated carbon as a hybrid supercapacitor electrode. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 289, 126476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.J. Characterization Studies on Adsorption of Lead and Cadmium Using Activated Carbon Prepared from Waste Tyres. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, R.; Fierro, V.; De Yuso, A.M.; Nabarlatz, D.; Celzard, A. Tetracycline adsorption onto activated carbons produced by KOH activation of tyre pyrolysis char. Chemosphere 2016, 149, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttil, N.; Jagadeesan, S.; Chanda, A.; Duke, M.; Singh, S.K. Production, types, and applications of activated carbon derived from waste tyres: An overview. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, E.L.; Ko, D.C.; McKay, G. Production of active carbons from waste tyres—A review. Carbon 2004, 42, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Z.; Kang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, J.; Liang, F. Activated carbon prepared from waste tire pyrolysis carbon black via CO2/KOH activation used as supercapacitor electrode. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 2337–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.J. Non-graphitizing carbon: Its structure and formation from organic precursors. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2019, 21, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, B.E. X-Ray Diffraction Study of Carbon Black. J. Chem. Phys. 1934, 2, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscoe, J.; Warren, B.E. An X-Ray Study of Carbon Black. J. Appl. Phys. 1942, 13, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Han, X.; Jiang, X. XRD and TG-FTIR study of the effect of mineral matrix on the pyrolysis and combustion of organic matter in shale char. Fuel 2015, 139, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Bai, J.; Yu, J.; Kong, L.; Bai, Z.; Li, H.; He, C.; Ge, Z.; Cao, X.; Li, W. Correlation between char gasification characteristics at different stages and microstructure of char by combining X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4162–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.; Beyssac, O.; Benzerara, K.; Findling, N.; Tzvetkov, G.; Brown, G., Jr. XANES, Raman and XRD study of anthracene-based cokes and saccharose-based chars submitted to high-temperature pyrolysis. Carbon 2010, 48, 2506–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frusteri, L.; Cannilla, C.; Barbera, K.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Frusteri, F. Carbon growth evidences as a result of benzene pyrolysis. Carbon 2013, 59, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, A.; Satonaga, T.; Kamada, K.; Sato, H.; Nikl, M.; Solovieva, N.; Fukuda, T. Crystal growth of Ce: PrF3 by micro-pulling-down method. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 270, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnoir, H.; Huo, D.; Davoisne, C.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V.; Saurel, D.; El Marssi, M.; Benyoussef, M.; Meunier, P.; Janot, R. Pyrolysis temperature dependence of sodium storage mechanism in non-graphitizing carbons. Carbon 2023, 208, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald-Wharry, J.S.; Manley-Harris, M.; Pickering, K.L. Reviewing, combining, and updating the models for the nanostructure of non-graphitizing carbons produced from oxygen-containing precursors. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 7811–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antil, B.; Elkasabi, Y.; Strahan, G.D.; Vander Wal, R.L. Development of graphitic and non-graphitic carbons using different grade biopitch sources. Carbon 2025, 232, 119770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellick, G.S.; Chang, D.J.; Zaldivar, R.J. Mechanisms of orientation and graphitization of hard-carbon matrices in carbon/carbon composites. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 2798–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, Z.U.; Chuan, L.K.; Guan, B.H.; Ahmad, F.; Ayub, S. A comparative study on the crystalline and surface properties of carbonized mesoporous coconut shell chars. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, M.; Nurhayati, D.; Maddu, A. Study of Structural and Electrical Conductivity of Sugarcane Bagasse-Carbon with Hydrothermal Carbonization; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; p. 012049. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-M.; Lee, S.-H.; Roh, J.-S. Analysis of activation process of carbon black based on structural parameters obtained by XRD analysis. Crystals 2021, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldevi, T.; Raghu, S.; Kalaivani, R.; Shanmugharaj, A. Waste tire derived carbon as potential anode for lithium-ion batteries. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Paranthaman, M.P.; Akato, K.; Naskar, A.K.; Levine, A.M.; Lee, R.J.; Kim, S.-O.; Zhang, J.; Dai, S.; Manthiram, A. Tire-derived carbon composite anodes for sodium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 316, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Y.; Ishibashi, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Wakizaka, H.; Iwashita, N.; Kenjo, S.; Nishikawa, G. Activated carbon production by co-carbonization of feathers using water-soluble phenolic resin under controlled graphitization. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2015, 4, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proximate Analysis (%) | Ultimate Analysis (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 1.8 | Carbon | 76.1 |

| Ash | 16.6 | Sulphur | 2.24 |

| Volatile Matter | 18.8 | Hydrogen | 2.52 |

| Fixed Carbon | 62.8 | Nitrogen | 0.47 |

| Oxygen | 0.3 | ||

| Samples | Pyrolysis Condition | Activation Condition | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio TPC: KOH | Temperature °C | Time min | |||

| AC 1 | 550 °C temperature with a heating rate of 6 °C/min for three hours | 1:2 | 800 | 30 | 292 |

| AC 2 | 1:1 | 800 | 60 | 255 | |

| AC 3 | 1:2 | 800 | 60 | 411 | |

| AC 4 | 1:2 | 800 | 90 | 507 | |

| AC 5 | 1:2 | 700 | 60 | 323 | |

| AC 6 | 1:3 | 800 | 60 | 343 | |

| AC 7 | 1:0 | 800 | 60 | 64.4 | |

| Samples | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | 2θ (°) | D002 (Å) | Lc (Å) | Crystalline Fraction (%) | Amorphous Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC 1 | 292 | 24.37 | 3.65 | 11.31 | 56.88 | 43.12 |

| AC 2 | 255 | 24.52 | 3.63 | 11.70 | 54.21 | 45.79 |

| AC 3 | 411 | 24.51 | 3.63 | 10.93 | 53.14 | 46.86 |

| AC 4 | 507 | 24.54 | 3.62 | 10.79 | 52.77 | 47.23 |

| AC 5 | 323 | 24.60 | 3.62 | 11.10 | 57.17 | 42.83 |

| AC 6 | 343 | 24.88 | 3.58 | 9.71 | 51.18 | 48.82 |

| AC 7 | 64.4 | 24.66 | 3.61 | 14.06 | 66.29 | 33.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zerin, N.H.; Rasul, M.G.; Jahirul, M.I.; Sayem, A.S.M.; Quadir, Z.; Haque, R. XRD Characterization of Activated Carbons Synthesized from Tyre Pyrolysis Char via KOH Activation. Technologies 2025, 13, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120565

Zerin NH, Rasul MG, Jahirul MI, Sayem ASM, Quadir Z, Haque R. XRD Characterization of Activated Carbons Synthesized from Tyre Pyrolysis Char via KOH Activation. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120565

Chicago/Turabian StyleZerin, Nusrat H., Mohammad G. Rasul, Md I. Jahirul, Abu S. M. Sayem, Zakaria Quadir, and Rezwanul Haque. 2025. "XRD Characterization of Activated Carbons Synthesized from Tyre Pyrolysis Char via KOH Activation" Technologies 13, no. 12: 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120565

APA StyleZerin, N. H., Rasul, M. G., Jahirul, M. I., Sayem, A. S. M., Quadir, Z., & Haque, R. (2025). XRD Characterization of Activated Carbons Synthesized from Tyre Pyrolysis Char via KOH Activation. Technologies, 13(12), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120565