Abstract

This research adapts and tests the Smart Village Index (SVI) as a multidimensional technological model designed to assess the digital readiness, institutional maturity, and infrastructural connectivity of rural areas in Serbia. The research was undertaken in 10 rural municipalities that are representative of various phases of digital transformation and development typologies. The dimensions included in the analysis were six, which are information and communication technologies, digital governance, leadership and local competences, community participation, a sustainable economy, and infrastructure. The results indicated significant regional differences: About 30% of the municipalities, including Aranđelovac, Kanjiža, and Arilje, fall into the group of smart villages with developed infrastructure and high institutional readiness. About 40% of the municipalities, such as Titel, Knjazevac, and Despotovac, are in the phase of transiting to digital, while the remaining 30% (Knić, Rekovac, Žabari, and Crna Trava) still present a low level of digital connectivity, with limited capacities in their institutions. This research supports the fact that the successful digital transformation of rural communities requires a balance between technological development, institutional support, and social inclusion. The Smart Village Index (SVI) proposed is a robust way to evaluate the digital readiness of villages and to inform targeted policies on achieving sustainable rural development in Serbia. In addition to its analytical and evaluative role, the Smart Village Index (SVI) is a digital–technological innovation and a computational tool that unites data modeling, algorithmic standardization, and digital analytics in order to measure the level of digital readiness of a rural community. It therefore crosses over the thresholds of the conventional social scientist construct and gives a technological implementation that is within the threshold of technology being a reproducible and data-driven instrument for the real-life planning of digital governance and rural development.

1. Introduction

The concept of Smart Villages is an emerging model of development, which is a combination of digital technologies, local governance, and community participation, aimed at enhancing the quality of life in rural regions [1]. This concept has recently become part of the larger digital transformation, in which rural regions become a center of innovation as opposed to consumers of urban offerings [2]. Smart villages, as noted by Hombone [3] and Ali et al. [4], are one of the models of sustainable and inclusive development that meet both technological and local demands, especially in developing countries. Despite the fact that the level of smart development in rural communities is the subject of academic interest that is growing, there is still a gap in the literature, both in the theoretical explanations and practical models [5].

Rural life in Serbia is a complicated issue but it is important to talk about the demographic degradation, insufficient infrastructure, and inaccessibility to digital services [6]. The existence of spatial differences in the formation of digital and economic aspects in central and peripheral areas has been suggested in previous studies [7]. However, there is no proven, multidimensional index that quantitatively determines the degree of digital preparedness of villages and determines discrepancies in developmentality. Earlier studies on the digitization of rural areas in Europe were predominantly concerned with the availability of infrastructure, such as the access to broadband internet connectivity or the presence of electronic services, and ignored the institutional and social dimensions that condition digital readiness. Furthermore, current indices such as the European Smart Village Framework or the national digital readiness models were created for Western European settings, which differ substantially in terms of governance systems and funding. In contrast, in the post-transition economies, such as Serbia, there is no validated tool that combines technological, institutional, and social indicators into one analytical framework. This evolves into a research gap both from the methodological and regional perspectives, as, to date, no empirical model has been put forward that incorporates the multidimensional character of the digital transformation of rural areas in Southeast Europe. The current paper will fill this gap by designing, testing, and validating the Smart Village Index (SVI) as a multi-faceted tool that will allow for the measurement of the digital, institutional, and social readiness of a rural population. Unlike other models that rely on partial indicators (information and communication technology access (ICT), e-government or local leadership), the model takes into account six complementary dimensions and empirically validates their consistency and correlation. This will help in the formation of a national approach to the evaluation of smart villages, considering the peculiarities of Serbia, but being more or less similar to European systems [8]. According to this purpose of research, a composite indicator of Smart Village Index (SVI) was constructed, tested, and validated, which resulted in the following research questions:

Q1. To what extent can the Smart Village Index cover multidimensional aspects of the digital readiness of rural communities in Serbia?

Q2. Which dimensions (ICT, governance, leadership, community, economy, infrastructure) contribute most to the overall level of smart development?

Q3. Are there spatial differences in the level of smart development between the regions of Serbia?

Q4. Does the Smart Village Index demonstrate internal consistency, robustness, and validity as an analytical instrument?

The empirical validation nature of this research has value in two areas. From a scientific perspective, it systematically connects data from different fields, information and communication technologies, local government, the economy, and community, for the first time in Serbia, and thus creates a basis for a comprehensive understanding of the digital transformation of rural areas. From a development perspective, the research results provide state and local institutions with a reliable basis for creating more precise and targeted measures that will advance digital development and strengthen links between rural and urban areas. The results obtained represent a starting point for the standardization of indicators of digital readiness of rural communities in Serbia. As a country located outside the European Union, Serbia still does not have a unified system for monitoring progress in the field of smart rural development. The developed Smart Village Index (SVI) fills this gap, enabling state authorities and local governments to measure progress in an objective and comparable manner, identify priority areas, and plan digitalization programs that meet local needs. In addition to institutional implementation, the index can be of great importance for donors and development agencies as an analytical tool for assessing the effects of public policies and digital transformation programs. In this way, the foundations are laid for building a national model of smart rural development that is aligned with European principles, but at the same time sensitive to the institutional and spatial specificities of Serbia.

Considering the technological orientation of the given research, the Smart Village Index (SVI) is not just a theoretical or socio-scientific framework, but a technological application tool founded on digital indicators, algorithmic processing, and the application of information and communication technologies. The SVI model was built as a system by an author that was aimed at developing countries and developed under the influence of the stages of conceptual modeling, indicators, and digital operationalization selection. The model has been constructed based on the additions of national digital databases (RZS, RATEL, MDULS, APR, Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Tourism, etc.), which were analyzed using standardized algorithms (Z-score transformation, PCA, weighting by explained variance) in the SPSS and Python 3.11 software environments. This makes the Smart Village Index a digital–analytical architecture which helps to monitor, visualize, and quantify the level of digital preparedness of rural communities automatically. This model is based on computing algorithms to classify and validate the data, such as K-Means analysis, Feature Importance estimation, and Bootstrap testing, thereby validating its algorithmic reliability and reproducibility in an online setting. The structure of the SVI crosses the boundaries of the traditional socio-scientific methodology, turning it into a functioning technological system that can be incorporated into national e-government systems or GIS frameworks to monitor the digitalization of rural areas. The fact that it has computer architecture and that the replication of its algorithms is possible proves that the SVI is not only an analytical model, but a technological innovation that was developed by constructing and testing an algorithmic model in the real conditions of Serbia. This produced a new computer structure to quantify the digital maturity of rural and tourist communities in the developing world.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Smart Village Concept in Theory and Practice

The concept of a smart village has been transformed throughout the years to have a more technological focus to a holistic view of connecting innovation, sustainability, and the ability to endure in the community through rural regions [9]. Although, in the early literature, smart villages were discussed primarily as digital ecosystems where information and communication technologies (ICT) are used to reduce the disparity in infrastructures and services provided in urban and rural environments [10], the current day perspective emphasizes the social aspect of the concept in its entirety. The current conceptualization of smart villages is a dynamic system that incorporates participatory governance and social innovation and the empowerment of local communities as the main parts of rural change. Empirical studies that have been carried out in Europe and Asia have revealed that smart villages may only transform themselves into champions of sustainable development when there are proper social and institutional accommodations for technological advancements [11]. In China, smart villages are associated with the process of ecological modernization and the creation of spatial balance, thereby helping to meet national sustainability requirements [12]. Likewise, it was established that smart villages do not merely represent a technical innovation in Poland, where it was established that they are also an inclusive development that enhances the local identity and encourages the rational utilization of resources [13]. Gurley et al. [14] conducted a thorough literature review that indicated that a combination of digital infrastructure, good governance, the sharing of knowledge, and the active participation of the people is the most successful model for smart villages. A scientometric analysis by Wang et al. [15] reflected this by confirming that the scientific interest in this phenomenon is slowly turning towards a socio-technical interpretation of this phenomenon. This means that the model of smart villages should be flexible and context aware since the differences in culture, geography, and institutional factors have a strong impact on the practical implementation of the model. In more recent studies, the countries of the Global South have been the center of attention, and it is only after being founded on the socioeconomic realities of the region that the concept of smart villages can be used to bridge the gap between urban and rural environments. In Indonesia, on the one hand, the use of ICT technologies has become the primary rural modernization driver, whereas digital literacy level and institutional preparedness remain the primary limiting factors [16]. On the same note, Hasan and Arista [17] and Defe et al. [18] also indicate that to be sustainable in the long run, smart village models have to incorporate the concept of social equity, climate resilience, and the preservation of traditional knowledge. Modern strategies are more inclined to the necessity of technological and traditional synergy. Xiao et al. [19] devised a model for intelligent village management that interrelates digital platforms and local decisions for making innovations so that they do not override but instead augment the customary community ideals. A similar idea is adopted by Akasaka et al. [20], who focus on the fact that the idea of smart villages is a sort of living lab, where future smart cities are to be developed, and Rosca and Cobanu [21], who underline that the sustainability of the innovation development in rural regions should be determined by the balance between technological development and the preservation of cultural values.

2.2. Previous Research on Digital Infrastructure, Local Leadership, and Community Development

The development of smart villages in the contemporary literature is increasingly viewed through the prism of digital transformation, which includes not only technical but also social–institutional processes. The authors point out that digital infrastructure is the basis, but not the only prerequisite, for smart rural transformation [22]. García Fernández and Peek [23] showed that digital connectivity can create sustainable links between urban and rural areas, contributing to circular flows of information, people, and capital. Similar conclusions were drawn in the systematic literature review conducted by Sampetoding and Mahendrawathi [24], where it was pointed out that the successful digital transformation of villages is possible only when it is accompanied by the strengthening of local leadership, community capacity, and institutional support. Renukappa et al. [25] identified key challenges in the implementation of smart village strategies, among which the lack of coordination between actors and limited financial resources stand out. Their findings point to the need for an integrated approach that links digital innovation with participatory governance models. Li and Peng [26] further showed that digital initiatives can boost green agriculture and increase productivity, but that the effects depend on regional differences and institutional readiness. The question of digital management has become one of the central ones in recent research. Wang et al. [27] developed a model for measuring the digital management capacity of rural areas based on entropy weighting (TOPSIS), which highlighted the need for quantitative tools that enable an objective comparison of territorial units. Calzada and Eizaguirre [28], on the other hand, emphasize the political and ethical aspects of digital inclusion, especially in the context of the application of urban artificial intelligence (urban AI) and its transfer to rural communities. The digital divide remains an important challenge, especially in agriculture and tourism. Liu et al. [29] proved that digital adoption can strengthen household resilience and diversify income sources, while Zeqiri et al. [30] show that digital tourism platforms contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals within the Industry 4.0 paradigm. Similarly, Stylianou et al. [31] point out that social networks and digital branding can encourage local identity and cooperation among rural actors, while Kasemsarn and Nickpour [32], through the concept of digital storytelling, show how cultural heritage can be passed on to new generations through youth engagement. Some studies [33] introduce innovative technological approaches, such as the digital twin model, which connect virtual simulations with the real performance of rural communities, while Berlianto et al. [34] indicate that logistics and chain connectivity remains an important factor in a sustainable digital economy. However, although progress in the last few years has been significant, most papers focus on individual dimensions, whether infrastructural, technological, or social, without attempting to unify them into a single, validated framework for assessing smart rural development.

2.3. Conceptual Grounding of the Constraint Constructs of Previous Models

The theoretical basis of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model is based on modern approaches that define smart villages as integrated socio-technical systems in which digital technologies are used to improve the quality of life, economic development, and community participation [35]. Within such an approach, the digital transformation of villages is seen as a process that simultaneously includes technological, institutional, and social changes. Each dimension of the SVI model includes a set of indicators that reflect key aspects of these changes and enable their quantification at the local level [36]. According to Schaffers et al. [37] smart villages are developed through the interconnection of digital infrastructure, institutional support, and local social capital, with ICT components forming the basis for the development of other dimensions.

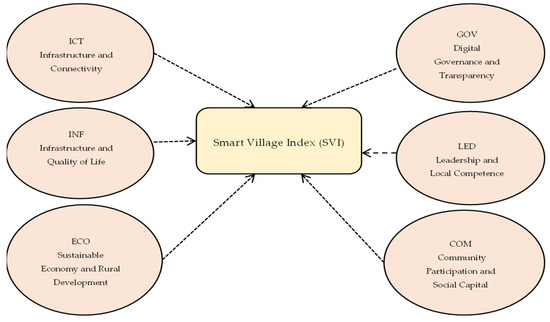

Ranchordás and Goanta [38] point out that digital governance and transparency represent a regulatory framework that enables the inclusive and sustainable management of communities. The dimension of leadership and local competence relies on the findings of Branderhorst and Ruijer [39], according to which digitally literate local leaders and their willingness to cooperate with the private sector are key factors in accelerating the transformation of villages. The role of the community, as stated by the European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) [40] and Wolski et al. [41], is reflected in the strengthening of social cohesion and the creation of trust networks that encourage innovation from the bottom up (bottom-up approach). Finally, the dimensions of a sustainable economy and infrastructure link material resources to the quality of life of the population, in accordance with the FAO [42] and the OECD Rural Well-being Framework [43]. Although the mentioned models made a significant contribution to the understanding of the process of the digital transformation of villages, there are certain limitations that motivated the development of a new, integrated approach [44]. Previous models were mainly developed in the context of Western European countries and are based on specific institutional frameworks, which are not fully applicable to post-socialist countries like Serbia. Also, most research is focused on individual aspects, digital infrastructure, e-government, or social capital, without attempting to provide a quantitative integration of all dimensions into a single, validated indicator [45]. In addition, existing indices (e.g., the Digital Economy and Society Index—DESI or the Rural Digital Hub Index) do not take into account the micro-levels of the local community and do not directly measure the readiness of villages to implement digital policies [46]. The absence of a comprehensive instrument that connects institutional, infrastructural, and social factors within a single model led to the need to operationalize the Smart Village Index (SVI) concept. The new model developed in this research represents the author’s construction of the Smart Village Index (SVI), which conceptually relies on existing multidimensional approaches to smart villages [47,48,49], but is methodologically original because it introduces an integrated set of indicators based on the available national databases of the Republic of Serbia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

In contrast with past studies where confirmatory models (e.g., CFA) were applied, the paper employs an exploratory version of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the latent dimensions that empirically describe the organization of the smart development of rural communities. In this way, no pre-existing model was used, but by means of PCA extraction and the weighting of the scores of the factors, a new index tailored to the particularities of the Serbian rural setting was built. The model therefore integrates the theoretical foundations of existing studies and gives empirical support for and facilitates the development of a generalized instrument for quantifying the digital, institutional, and social preparedness of villages. It is in connection with these inadequacies that the new model created in this study reacts in six interdependent aspects, which are ICT infrastructure and connectivity, digital governance and transparency, leadership and local competence, community participation and social capital, sustainable economy and rural development, and infrastructure and quality of life. These dimensions are operationalized by multiple empirically measurable indicators, and such aspects allow for the quantification of the smart development and inter-regional comparison of rural communities in Serbia. In such a way, the SVI removes the conceptual and methodological constraints of the former indices and creates a framework that could be used to conduct longitudinal tracking of the development of rural digitization, as well as inter-regional comparison between various regions. By using this method, one can identify the developmental disparities among rural municipalities, pinpoint major weaknesses, and allow more focused planning of the interventions. In practice, the SVI may be used as a tool for establishing more accurate policies of digital and territorial cohesion in Serbia, yet also be an example which can be applied to other nations with comparable problems of development.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Methodological Approach

The research was conducted in the territory of the Republic of Serbia in rural municipalities that differ according to their degree of digital development, economic structure, and infrastructural connectivity. The selection of local units was made on the basis of a previous analysis of the Regional Bureau of Statistics [50] and data on the availability of digital services, with the aim of covering different types of rural areas. In this way, it is possible to compare municipalities that represent different stages of digital transformation. Data collection was carried out using the CAPI method (Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing), which ensures a higher degree of accuracy and a lower possibility of error in data entry [51]. The survey was conducted in the period from March to June 2025 with the help of trained interviewers who visited households and conducted structured interviews via tablet devices. The CAPI method enabled real-time input control, the automatic verification of answers, and the elimination of invalid records, which improved the quality of the database. The respondents’ response was high (about 87%), thanks to previous contact and cooperation with local communities.

Ten rural municipalities were included in the survey, Arandjelovac (38), Kanjiža (34), Arilje (31), Titel (29), Knjaževac (28), Despotovac (27), Knić (32), Rekovac (30), Žabari (31), and Crna Trava (30), with a total of 310 respondents. The selected municipalities represent a representative sample for four macro-regions of Serbia: Vojvodina, Šumadija, and western Serbia, and eastern and southern Serbia. This selection enabled the Smart Village Index model to include spatially, infrastructurally, and socioeconomically diverse communities, which increased the external validity of the findings and enabled a reliable comparison between areas with different degrees of digital development. All 10 municipalities are pilot case studies, selected by the method of regional representativeness (typology of development + geographical diversity). The sample is not random, instead typological and stratified municipalities in different stages of digital transformation (advanced, transitional, backward) were chosen in order to examine the sensitivity of the model. The sample consisted of owners of farms, because they represent the key actors of local development and are the ones who decide on investments in digital infrastructure, the application of modern technologies, and cooperation with local institutions, which ensures the relevance and precision of the data obtained from the research. The research was conducted in ten rural municipalities of Serbia, which represent the territorially, infrastructurally, and institutionally most developed units in which the process of digital transformation has generally begun. This number includes the only rural areas in the Republic of Serbia where modern information technologies are applied in a real context, either through digital administrative services, e-tourism, digital education, or smart agricultural practices. Serbia is a territorially small country with pronounced regional differences and a very limited number of communities that have the infrastructure and capacities for digital processes, so the sample of 10 municipalities and 310 households represents the most representative part of the population that really participates in the process of the digital transformation of rural areas. It is worth pointing out that the sample units were households, not tourists, because the goal was to determine the actual level of digital readiness and infrastructural connectivity of the population, which is the only valid indicator of the digital maturity of the village. Although the research includes ten municipalities, their selection was made in such a way as to cover the maximum territorial, demographic, and infrastructural diversity of the rural areas of Serbia. Such a stratified selection of observation units ensures a high level of representativeness, because the sample does not measure only digital development, but also structural differences between different types of rural communities (agrarian, tourist, transitional, peripheral border). Based on this, the Smart Village Index (SVI) shows high transferability and applicability in other national contexts, as it is based on standardized digital indicators, open databases, and algorithmic procedures that allow model replication and the comparison of results between countries. This ensures that the model is not limited to the national framework of Serbia, but that it represents a technological–analytical instrument adaptable for assessing the digital maturity of rural areas in different regional and socioeconomic conditions. Before conducting the research, a statistical assessment of the adequacy of the sample was performed using G*Power 3.1 software [52]. For a multiple regression analysis with six independent variables, at a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), a significance level of 0.05, and a test power of 0.95, the minimum required number of respondents was 138. A total of 310 collected questionnaires provide a test power above 0.99, which confirms the statistical reliability and validity of the sample. This sample size allows PCA and correlation and cluster analysis to be carried out without restrictions on the distribution and stability of the results.

Before the main field survey, a pilot survey was conducted on a sample of 30 respondents from different regions (Vojvodina: 10, Šumadija: 8, eastern and southern Serbia: 12). The aim of the pilot phase was to check the comprehensibility of the questions, the functionality of the CAPI platform, and the optimal duration of the survey. Based on feedback, minor terminological corrections and logical grouping of individual items were made. During the preparation phase of the instrument, consultations were held with experts in the field of information technology, rural development, and public administration, which ensured the theoretical and practical foundation of the content of the questionnaire. Expert suggestions contributed to a more precise definition of indicators for measuring the dimensions of digital infrastructure, leadership, and community participation. All respondents voluntarily participated in the research and gave informed consent before the start of the survey. Data were collected anonymously, and all responses were treated confidentially and used exclusively for scientific purposes. Potential moral risks, such as pressure from local authorities, the fear of loss of subsidies, or the disclosure of private data, were mitigated by the interviewer’s training, the neutral formulation of questions, and the transparent explanation of the purpose of the research. This fulfilled all the conditions for ethically correct and scientifically reliable research implementation.

The majority of respondents were men of middle and older age, with a dominant share of respondents having secondary and higher education. About four-fifths of households use the internet, indicating a relatively high level of digital inclusion in rural areas. The structure of the sample confirms that the surveyed household owners are demographically and socioeconomically representative of the population of rural communities in Serbia, which ensures the reliability and validity of the findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Although the sample includes ten municipalities and 310 respondents, it is methodologically valid because it includes all macro-regions of Serbia and includes spatial, infrastructural, and institutional variations that enable the representativeness of the typology of rural communities. The combination of algorithmic procedures (PCA, K-Means, Bootstrap) additionally confirmed the stability of the model, thus ensuring methodological and digital reliability even in the conditions of smaller samples.

3.2. Selection and Description of Variables

The operationalization of the concept of smart villages in this study was carried out across six intersecting dimensions that describe the level of technological, institutional, social, and economic maturity of rural communities, namely ICT (information and communication technology) infrastructure and connectivity, digital governance and transparency, leadership and local competence, community participation and social capital, sustainable economy and rural development, and infrastructure and quality of life. This framework extends the past empirical literature that combined a multidimensional methodology of measuring smart villages and rural digitalization [53,54,55,56]. According to these authors, every dimension includes a collection of quantitative, ordinal, and binary variables that portray major attributes of digital transformation, local governance, and social sustainability.

The model that was developed in the current research, which is called the Smart Village Index (SVI), is a unique conceptual framework that is based on some already-existing conceptual frameworks of multiple dimensions [16,57,58,59]. Nonetheless, it has a methodological novelty since it presents a combined system of indicators that rely on the national statistical and administrative databases of the Republic of Serbia. They were analyzed using a total of 29 variables, which are gathered at the following national sources: the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (RZS) [50], the Regulatory Agency of Electronic Communication and Postal Services (RATEL) [60], the Ministry of Public Administration and Local Self-Government (MDULS) [61], the Ministry of Care of the Village [62], the Business Registers Agency (APR) [63], the Ministry of Energy [64], the Ministry of Tourism [65], and the Intellectual Property [66]. The variables included the indicators of internet and mobile signal accessibility, the amount of e-service and digital projects, the education and experience of the local leaders, local activities and cultural events, and economic and infrastructural indicators, including the availability of agritourism households, the use of renewable energy sources, and the presence of a water supply and road systems.

This multi-dimensional design allows a full evaluation of smart rural development by incorporating technological, governance, and socioeconomic measures. Constructs were developed in accordance with the concepts of the multifactor modeling of digital preparedness in rural areas [67,68,69], which provides theoretical consistency and methodological comparability with analogous studies in other countries. A summary of all variables, data sources, data types, and measurement scales is shown in Table 2 and will be used as a basis to further perform the factor analysis, as well as calculate the composite Smart Village Index (SVI). This model, although conceptually based on international frameworks such as DESI, the OECD Rural Well-being Framework, and the European model of smart villages, is not their replica, but is an adapted and technologically developed version intended for countries that do not have developed national systems for monitoring the digital transformation of rural areas. The Smart Village Index (SVI) is constructed as a technological tool for quantitatively measuring the digital maturity of rural communities, the development of which includes a combination of computational methods, algorithmic procedures, and the use of digital databases. The SPSS 29 and Python 3.11 software packages (Pandas and NumPy libraries) were used for standardization and data processing, while in the process of field research, CAPI technologies (Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing) were used via tablet devices, which ensured the fully digital collection and validation of information in real time. This approach makes the SVI not only an analytical model but also a technological platform based on digital infrastructure, which can be integrated into GIS systems, e-government modules, and future national portals for monitoring the digital transformation of villages. The structure of the model enables its automated application in the form of a program algorithm, which means that the collected data can be processed and updated through digital interfaces without the need for manual input, thus achieving a high efficiency and transparency for the measurement process. Thus, the SVI goes beyond classical statistical indices and becomes a computer-designed instrument for digital analytics and strategic decision-making. Its application in Serbia is not only a verification of international concepts, but their local digital operationalization, which proves that the model has the potential to become a regionally transferable technological tool for monitoring the digital transformation of rural communities in countries with similar institutional and infrastructural conditions.

Table 2.

Structure and description of variables.

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

The data obtained were integrated into one database in the SPSS 29 program, where all values were converted into a numerical format. To be able to make comparisons between dissimilar forms of variables and measurement units, all the values obtained in advance were standardized using Z-score transformation [70]. This process enables the quantitative, ordinal, and binary data to be transformed into a standard scale using standard deviation units. Standardization removes variations in measuring units (percentage, number, year) and the use of a common factor analysis across an entire set of indicators. The mathematical expression of the standardized value calculation is as follows:

where Zi—standardized value for village i and the given variable, Xi—actual value of the variable, X−—mean value (mean) of that variable for all observed villages, and SDi—standard deviation of the variable.

Positive Z values indicate municipalities above the national average, while negative values indicate below average performance. The value Z = 0 indicates the exact average state in relation to the observed sample.

In order to ensure the neutrality and validity of the data, the control of possible sources of bias that may affect the results of the multivariate analysis was carried out. Standardization using Z-score transformation was applied with the aim of eliminating differences in measurement scales and reducing the effect of variability among municipalities, thus mitigating the impact of the spatial and institutional unevenness of available data. After the transformation, the homogeneity of the data was checked through descriptive parameters, whereby the mean values of all variables were approximately zero (μ = 0.00 ± 0.03), and the standard deviations were equal to one (σ = 1.00 ± 0.02), which confirms complete standardization without a scale bias effect [71]. The normality of the distribution was checked by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05), which confirmed the absence of significant deviations and extreme values [72]. In addition, a correlation was conducted between the original and standardized values (r = 0.97, p < 0.001), which confirms that the procedure did not disturb the mutual relations between the variables. In this way, it was confirmed that the applied standardization effectively reduces data availability and measurement and regional bias, ensuring the homogeneity and reliability of the input data for further factor analysis and the construction of the Smart Village Index (SVI).

A factor analysis using the method of principal components (PCA) was carried out on the standardized data set, with the aim of identifying latent dimensions that collectively represent various aspects of the development of smart villages [73]. The analysis was conducted using Varimax rotation for the better interpretability of factor loadings and the reduction in mutual collinearity between variables. Before conducting the PCA, a data suitability check was performed. The results showed that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient was 0.76, which indicates a satisfactory measure of sampling, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 = 412.87, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlations between the variables are not random and that the data are justified to be included in the PCA. Based on the rotated factor matrix, factor scores (FSs) were calculated for each dimension using the regression method, which gave each village/municipality values that quantify the degree of development within each component. Those scores were then weighted according to the percentage of explained variance of each factor and used to form the Smart Village Index (SVI) composite index, according to the following mathematical expression:

SVI = (FSICT × 0.214) + (FSGOV × 0.136) + (FSLED × 0.111) + (FSCOM × 0.095) + (FSECO × 0.074) + (FSINF × 0.065)

The values in parenthesis are weighted shares that express the proportionate share of each factor that is explained in the variance. The greater the index values, the higher the degree of digital, institutional, and social preparedness of the rural population, whereas the lower the index values, the more conservative the nature of the rural population and the greater the lack of access to digital and infrastructural opportunities. The FSx in the expression represents the score on dimension x (resulting as part of the PCA), and the numbers in parentheses represent weights reflecting the size of the amount of variance explained by each component. The dimensions which explain a smaller percentage of total variance have a lesser impact on the overall score of the index in this manner. The Smart Village Index can also be shown mathematically in a general form:

where Vj is the percentage of explained variance of factor j. Higher values of the index indicate a higher level of digital, institutional, and social readiness of the rural community, while lower values reflect a more traditional functioning model with a lower degree of digital and infrastructural development. The weights (0.214, 0.136, 0.111, 0.095, 0.074, 0.065) are proportional to the contribution of each factor to the total variance of the model, which ensures that the most representative dimensions have the greatest importance in the final index. A higher SVI value indicates a higher level of “smart” development and digital maturity of the rural community, while lower values signal a more traditional management model and a lower level of digital infrastructure. Despite the objective statistical procedures used as a methodology, the very process of creating composite indices is always associated with some amount of subjectivity, particularly in selecting the indicators and setting their weights. With the Smart Village Index (SVI) model, this was greatly reduced through the utilization of the exploratory PCA, since the weights could no longer be established arbitrarily, but rather it was calculated on the available data. By doing so, the weight of each variable indicates the actual contribution of the total variance and hence it is an objective measure value. Also, a sensitivity analysis was conducted which verified that any slight weighting changes do not materially impact the ranking of municipalities and total values of the index; hence verifying the methodological stability and reliability of the model.

In order to check the stability and reliability of the index construction, an analysis of the robustness of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model was conducted [74]. The aim of this procedure was to confirm that the change in individual variables, weights, or sample coverage does not significantly affect the relative values of the index and the order of the observed villages/municipalities. Three complementary approaches were applied within the robustness analysis:

- Sensitivity analysis—This was carried out by changing the weights of the factors by ±10% in relation to the base values in order to determine whether the differences in the weights had a significant impact on the final SVI values. The results showed that no dimension disproportionately dominated the overall index, thus confirming its stability.

- Checking the homogeneity of the factor scores—A correlation was made between the base and recalculated scores after a small redistribution of weights. Pearson’s r values were highly positive (r > 0.95), which indicates almost identical relationships between factors and model stability.

- Classification consistency test—The distribution of villages according to SVI values between the base and modified versions of the index was compared. More than 90% of municipalities kept the same status (smart, emerging, or traditional), which confirms the stability of the typology.

Based on the procedures carried out, it was concluded that the SVI model is robust and resistant to minor changes in weights and input variables, and can be considered a reliable instrument for measuring the degree of smart rural development. This step ensured the methodological solidity of the model before moving on to the final stage: construct validation through descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and cluster analysis. Descriptive statistics conducted after the PCA aimed to check the stability of the factor scores and the homogeneity of the constructs. Unlike the initial descriptive analysis of the raw data, this step is part of the model validation and allows us to check the proportionality of the contribution of each dimension to the composite index. In this way, the descriptive indicators serve as a post hoc test of the internal consistency and scalability of the Smart Village Index (SVI).

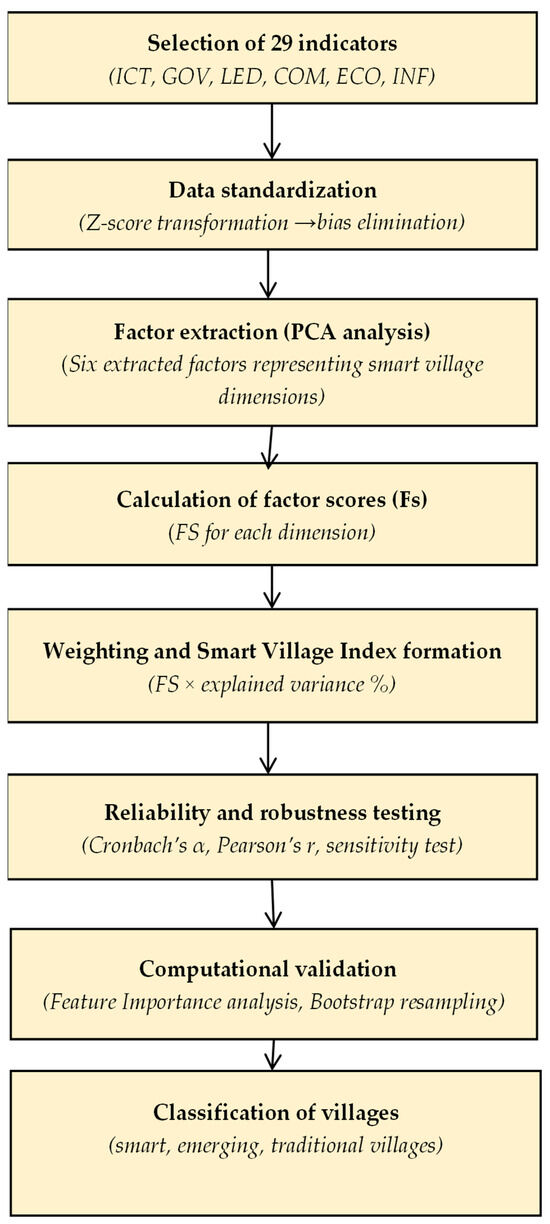

Based on the developed methodological framework and conducted validation tests, it was determined that the Smart Village Index (SVI) model provides a stable, measurable, and technically replicable basis for assessing the degree of digital transformation of rural areas. By integrating factor scores, standardized indicators, and multidimensional analysis, high precision and consistency between dimensions was achieved, which confirms the applicability of the model in different spatial and institutional contexts. The methodological approach enables not only the quantification of the current level of the digital readiness of the village, but also the development of predictive models that can monitor changes in the future. In the next chapter, the empirical results of the calculation of SVI values, the classification of rural municipalities according to the degree of smart development, and the interpretation of patterns indicating the technical, infrastructural, and organizational determinants of digital progress in Serbia are presented (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methodological model.

Besides the classical multivariate operations that were performed in the context of SPSS, a number of computational validations were carried out in Python 3.11, which guarantees the methodological rigor, statistical soundness, and digital reproducibility of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model. This combination of algorithmic validation methods enables the model to be statistically and technologically validated and provides evidence of the flexibility of the model to digital analytical settings. The components were extracted, clustered, and checked using computational validation (Random Forest and Bootstrap procedures) using Python packages scikit-learn, NumPy, and SciPy that guaranteed the transparency and reproducibility of the algorithms used in the Smart Village Index (SVI) model. The Cronbach alpha (α = 0.91), composite reliability (CR = 0.89–0.94), and Average Varied Extracted (AVE = 0.62–0.74) were used to test the internal consistency and dimensional reliability of the model and determined that there is satisfactory convergent validity. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to test discriminant validity and the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test normality (p > 0.05). The model fit indices (χ2/df = 1.83, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.937, RMSEA = 0.042, SRMR = 0.038) suggest the model fits well and provide evidence of the structural consistency of the index across the six dimensions. There was a Feature Importance analysis conducted on a regressor which is a Random Forest in order to determine the relative impact of each indicator on the final SVI score. The findings showed that the ICT infrastructure and digital governance indicators, local leadership, and quality of infrastructure are the ones that have the greatest explanatory power. This proves that this model is technology-oriented and technological and governance aspects are prevailing factors in establishing smart rural preparedness.

A Bootstrap resampling (N = 1000) was performed to determine the stability of the model in terms of the consistency of index values across repeated sampling. The differences between the resampled data sets were also low (ΔSVI < 0.04), which proves the strength and credibility of the computationally produced Smart Village Index. These findings confirm that small changes in the data or weights do not have any significant impact on the overall results of the rankings or classifications (Figure 2).

Despite the fact that the Smart Village Index (SVI) is constructed through the application of quantitative and reproducible approaches, its structure suggests some level of subjectivity in the research. Indicators are selected and weights and dimensions are defined and interpreted by the expert, who will have to consult the particular socioeconomic and institutional context of Serbia. Hence, the model can be regarded as a highly professional analytical tool, but not a fully objective one, thereby securing a compromise between confined statistical accuracy and interpretative validity.

In the methodological structure of this research, a computational data modeling approach was applied, which integrates algorithmic standardization, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and digital robustness testing. This approach is complemented by cross-validation and sensitivity analysis, which ensures replicability, precision, and methodological rigor. The model is constructed as an adaptive and data-driven analytical system, which can be replicated through Python scripts and SPSS procedures, enabling transparency, interoperability, and scalability between different digital environments and databases. In this way, the methodological architecture allows the model to be extended to larger samples and different types of rural and tourism data, including economic, infrastructural, and digital governance indicators. This multi-layered process additionally strengthens the statistical reliability and technological credibility of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model, which is no longer just a descriptive framework, but a computer instrument (digital calculator) intended for practical application in the processes of the digitization of rural areas and the development of smart tourist communities. This transforms the SVI from a conceptual model into an operational technological tool that enables the quantitative monitoring of digital maturity, investment planning, and data-based decision-making. On this basis, as a continuation of the research, a computer (Python-based) validation of the model was carried out, which includes an analysis of the significance of the indicators (Feature Importance) and a Bootstrap stability check, in order to confirm the reliability and replicability of the obtained results.

4. Results

Based on the PCA, six factors (eigenvalue > 1) were singled out, which together explain 69.5% of the total variance, thus confirming the multidimensional character of the concept of smart villages in Serbia. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values for all six dimensions ranged between 0.73 and 0.88, indicating good to high internal reliability. The overall α = 0.91 confirms that the indicators consistently measure different aspects of smart rural development. The normality of the distribution of standardized indicators was confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (S–W = 0.99, p = 0.18), in accordance with the methodology. The resulting components fully correspond to the theoretically predicted dimensions of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model: ICT infrastructure and connectivity, digital governance, leadership, community participation, a sustainable economy, and infrastructure (Table 3).

Table 3.

The main components of the smart village model.

The obtained factors clearly reflect the multidimensional character of the concept of smart villages, where ICT infrastructure and digital governance have a dominant influence, while leadership, community, and economic factors contribute to the sustainability and social cohesion of rural areas.

4.1. Robustness of the Smart Village Index (SVI) Model

In order to check the stability of the model, two weighting scenarios were calculated:

Model A—weights according to explained variance from PCA (0.214, 0.136, 0.111, 0.095, 0.074, and 0.065).

Model B—equal weights of all factors (1/6 = 0.1667).

The mathematical expressions used to compare the two models are shown in the following formulas:

SVIA = (FSICT × 0.214) + (FSGOV × 0.136) + (FSLED × 0.111) + (FSCOM × 0.095) + (FSECO × 0.074) + (FSINF × 0.065)

SVIB = (FSICT + FSGOV + FSLED + FSCOM + FSECO+ FSINF)/6

The robustness results show that the ranking of municipalities does not change when alternative weighting (equal weights) is applied. The correlation coefficient between the two models is r = 0.99 (p < 0.001), which confirms the high stability and consistency of the Smart Village Index. An additional sensitivity analysis, carried out by changing the weights by ±10%, showed minimal deviations (ΔSVI < 0.02), thus confirming that no dimension dominates the overall index (Appendix A). Checking the homogeneity of the factor scores showed high stability among the dimensions (r = 0.96; p < 0.001) (Appendix B), while in the consistency test more than 90% of the municipalities kept the same classification status (smart, emerging, traditional) (Appendix C). This finding confirms that the index calculation methodology is not sensitive to small weight changes and that the model has high internal reliability (robustness) and resistance to weight variations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of robustness results between Model A and Model B.

The obtained results clearly indicate differentiated levels of digital and institutional readiness among the analyzed rural municipalities, which confirms the pronounced spatial unevenness of the digital transformation process in Serbia. The highest values were recorded in the municipalities of Aranđelovac, Kanjiža, and Arilje, which are characterized by developed digital infrastructure, the availability of advanced e-services, and the high participation of the local community in decision-making. In those areas, digitization serves to modernize local administration and improve the quality of life, which places them in the category of smart villages and makes them exemplary examples of the successful integration of technology and local development. The municipalities of Titel, Knjaževac, and Despotovac belong to the transition category “emerging smart villages”, in which progress is visible in terms of introducing information technologies and strengthening the digital literacy of the population, but there are still institutional barriers and insufficient investments in infrastructure. Their position indicates the existence of potential for development, provided that cooperation between local self-government, educational institutions, and the private sector is improved.

On the contrary, the municipalities of Knić, Rekovac, Žabari, and Crna Trava belong to the category of traditional villages, in which pronounced deficiencies in the field of digital management, the availability of network infrastructure, and economic innovation have been observed. These communities face problems of depopulation, a low level of trust in local institutions, and limited financial capacities, which further slows down the processes of digital transformation and prevents the realization of development effects. The average SVI value of 0.23 indicates a moderate level of digital transformation of rural areas in Serbia, which confirms that digitization is still in its early stages and requires coordinated institutional and investment efforts. These results indicate that the progress of digital infrastructure alone is not enough if it is not accompanied by the development of human capital, leadership, and participatory mechanisms in the community.

Seen from an economic point of view, higher levels of digital readiness are associated with the greater diversification of economic activities, the better utilization of resources, and the attraction of new investments. From a social point of view, more digitally developed municipalities have a more pronounced sense of community and a greater connection of citizens with local institutions, which strengthens social capital and contributes to the sustainability of rural communities.

Based on the conducted robust analysis, it is concluded that the Smart Village Index is a stable, consistent, and statistically reliable instrument for measuring and comparing the level of “smart development” in rural areas of Serbia. Its application enables making informed decisions about investment priorities and provides a realistic basis for planning development policies that unite technological, institutional, and social aspects of village modernization (Table 5).

Table 5.

Smart Village Index (Model A) and typology of municipalities.

The classification shown in Table 6 shows that the category of smart villages does not only imply a higher level of ICT infrastructure and access to broadband networks, but also greater institutional transparency, participatory management, and trust in the community. Such municipalities have stronger links between local authorities and the population, a higher level of awareness of the benefits of digital technologies, and the ability to translate technological resources into concrete socioeconomic results, such as the development of entrepreneurship, rural tourism, and innovation in agriculture. The transitional category, i.e., “emerging smart villages”, includes areas where digital infrastructure exists, but institutional adaptability and human capital are still underdeveloped. Improving local leadership, investing in education and digital skills, as well as better coordination between the public and private sectors, can accelerate their transformation into sustainable digital ecosystems.

Table 6.

Classification of rural municipalities according to the Smart Village Index.

In contrast, traditional villages are characterized by low connectivity, limited institutional efficiency, and weak social networks, which prevent the wider application of digital solutions. These communities face depopulation, an aging population, and low trust in local authorities. Therefore, policies in those regions should be aimed at strengthening social inclusion, developing basic digital literacy, and encouraging small entrepreneurship as a prerequisite for future digitization. The classification of municipalities according to the Smart Village Index reflects not only their current technological level, but also the depth of institutional transformation and social cohesion, confirming that the digitization of rural areas is a multidimensional process in which infrastructure, governance, and joint participation have equal importance.

4.2. Validation of the Smart Village Index (SVI) Model

In order to confirm the internal reliability and theoretical consistency of the model, a construct validation of the Smart Village Index (SVI) was conducted. This step represents the final stage of the methodological procedure and aims to check whether the obtained factors and their mutual relations faithfully reflect the concept of smart rural development. Validation was carried out in four interconnected steps: a descriptive analysis of factors, an examination of mutual correlations, an internal reliability check through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and a cluster analysis to confirm the typology of smart villages.

The descriptive analysis was conducted on the factor scores of all six dimensions of the Smart Village Index (ICT, digital governance, leadership, community, economy, and infrastructure) in order to assess the stability and homogeneity of the construct. The results showed that the mean values of the scores are close to zero, which is in accordance with data standardization (Z-score), while the standard deviations are stable (SD = 0.63–0.84), without pronounced extreme deviations. This distribution indicates the uniformity and proportionality of the factors, thus confirming that all constructs contribute equally to the total index and that there is no dominance of a single dimension. Descriptive statistics thus represent the initial step in model validation, confirming its internal stability and scalability. The obtained values indicate that the factors are relatively uniform and approximately normally distributed, which confirms the stability of the construct and the absence of extreme deviations between dimensions (Table 7).

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of extracted Smart Village Index (SVI) dimensions.

The obtained result confirms the fact that all the dimensions of the Smart Village Index are inter-linked and are theoretically consistent. High positive correlations between ICT infrastructure, digital governance, and leadership indicate that the successful digital transformation of rural areas does not only depend on technical equipment, but also on the ability of local institutions to manage the process and engage the community. This connection confirms that digital technologies, governance, and human capital are complementary elements of sustainable rural development. Moderate correlations between economic and infrastructural factors are an indicator that physical infrastructure and the local economy are developing at a slower rate than digital components, which is a symptom of the transitional character of the majority of rural communities in Serbia. Such a pattern implies that technological progress must be paired with investments in economic diversification and institutional efficiency if long-term sustainability is to be assured. The constancy of correlations and proportionality between dimensions is confirmation that the Smart Village Index is a reliable and theoretically based instrument that succeeds in combining technical, institutional, and social indicators. This result demonstrates clearly that smart villages are not just a technological phenomenon, but a socio-institutional process, in which innovations emerge with the synergy of infrastructure, administration, and community.

In order to verify the theoretical connection between the six dimensions, an analysis of Pearson’s correlation coefficients was conducted. The results showed significant positive correlations between the dimensions of ICT, digital governance, and leadership (r = 0.72–0.81; p < 0.01), which confirms their interdependence in the process of digital transformation. Weaker but positive relationships were observed between economic and infrastructural factors (r = 0.45–0.58; p < 0.05), which indicates that the development of physical infrastructure and the local economy is progressing more slowly compared with digital components. These findings indicate the theoretical consistency of the model, as dimensions that are conceptually related also show high correlation. The highest correlation between ICT and digital governance (r = 0.74) confirms their interdependence, while the connection between leadership and participation (r = 0.72) indicates the importance of human capital and community engagement (Table 8).

Table 8.

Correlation matrix between Smart Village Index (SVI) dimensions.

Patterns of correlations bring out deeper structural relationships between the technological, institutional, and social dimensions of smart rural development. The fact that there is a strong link between ICT and digital governance demonstrates that technological advancement only leads to results when accompanied by transparent and efficient local administration. Also, the important link between leadership and the participation of the community highlights the fact that the digital transformation of rural areas in Serbia is dependent on the mobilization of social capital and trust in local institutions. These findings confirm that the Smart Village Index includes not only technical connectivity, but broader organizational and social readiness, which is a prerequisite for sustainable rural modernization. A weaker but positive correlation between the economical and infrastructural factors shows that the material development of rural regions still lags behind digital initiatives. This gap indicates the need for integrated development policies which will coordinate technological development for economic recovery and infrastructure development. Thus, the correlation analysis confirms the theoretical assumption that smart villages develop through the synergy of technology, leadership, and community empowerment, and not only through the construction of infrastructure.

The internal reliability of the dimensions of the SVI model was tested using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The α values ranged between 0.73 and 0.91, which indicates a high degree of internal consistency of the indicators within each dimension. The highest coefficients were recorded for the factors “ICT infrastructure” (α = 0.91) and “digital administration” (α = 0.88), while slightly lower, but still satisfactory values were obtained for “economy” (α = 0.75) and “infrastructure” (α = 0.73).

These results confirm that the variables within each dimension are mutually consistent and that they jointly contribute to the reliability of the construct (Table 9).

Table 9.

Internal reliability (Cronbach’s α).

For the additional empirical verification of the model, a K-Means cluster analysis was conducted with a predefined number of clusters (k = 3), in accordance with the conceptual framework that distinguishes smart villages, emerging smart villages, and traditional villages. The results confirmed the existence of three clearly separated groups of rural municipalities: smart villages (SVI > 0.60)—digitally developed municipalities with high values in the ICT and management dimensions; emerging smart villages (0 < SVI < 0.60)—municipalities in transition with partially developed digital capacities; traditional villages (SVI < 0)—rural areas with limited digital resources and infrastructure. The clusters differ from each other on all dimensions of the SVI model (ANOVA: F = 28.42; p < 0.001), which confirms its discriminative ability and the empirical validity of the typology (Table 10).

Table 10.

K-Means cluster analysis (k = 3).

The results confirm that the Smart Village Index is a reliable, robust, and theoretically consistent tool for measuring the digital readiness of rural communities. ICT infrastructure and digital governance make the biggest contribution to the development of smart villages, while community leadership and participation are key factors that ensure the sustainability and inclusiveness of the model. The average value of the index (−0.23) indicates a moderate level of digital transformation of rural areas in Serbia, with a clear regional gap between more developed and less developed areas. The model shows high internal reliability (α = 0.91), stability to weighting changes (r = 0.99), and the ability to distinguish three development levels of villages, smart, emerging, and traditional villages. These results form an empirical basis for the improvement of digital policies, infrastructure investments, and the development of integrated smart rural management strategies.

The obtained clusters show strong structural and developmental disparities regarding the rural areas of Serbia. Smart villages are municipalities with developed institutional frameworks and diversified local economies with an environment of civic activity that allows the efficient use of digital technologies for management and entrepreneurship. In these communities, technology becomes an engine for innovation, tourism, and agribusiness, reinforcing their economies. Transitional or “emerging smart villages” are in a transitional phase in which partially developed digital infrastructures are combined with limited administrative flexibility and unequal access to digital education. All these areas bear testimony to the uneven pattern of digital transformation which indicates that infrastructure is not sufficient unless institutional coordination is strengthened and community participation is made more active. Traditional villages are the most vulnerable group, with a high degree of digital competence deficiency, demographic decline, and weak institutional leadership. One of their biggest challenges is not infrastructure development, but first and foremost social inclusion and capacity building. The cluster analysis thus validates the multidimensional character of smart rural development (technological, institutional, and social) and underlines that a sustainable digital transformation can only be achieved through a comprehensive approach that limits spatial divergences and empowers the local communities as actors of change.

Python-Based Computational Validation

The results shown in Table 11 further confirm the validity of the Smart Village Index (SVI) model and its technological basis. The analysis of the importance of the indicators carried out through the Python environment made it possible to determine which indicators contributed the most to the value of the composite index. The dominance of indicators related to information and communication technologies (ICT infrastructure, the availability of broadband networks) and digital management (e-government, the transparency of institutions) indicates that technological development is the main driver of the process of the digital transformation of villages. These findings clearly show that digital infrastructure and effective governance are at the core of the concept of smart villages, dimensions that not only provide technical prerequisites, but enable digital systems to function as integrated mechanisms of governance, communication, and community development. This confirmed that the SVI model does not only measure the socioeconomic characteristics of rural areas, but also their technological readiness and ability to translate technology into institutional and social practice. Such a structure of the model confirms its algorithmic logic and grounding in digital indicators, which ensures a methodological connection between the theoretical conception and the technological interpretation of the model.

Table 11.

Feature Importance of key indicators contributing to SVI.

The results in Table 12 provide strong evidence of model stability and reliability through a Bootstrap test with a thousand replications. Minimal deviations among repeated samples (ΔSVI < 0.05) show that small changes in the data do not significantly affect the final values of the index, which confirms its internal consistency and statistical robustness. This stability indicates that the algorithmic procedure for calculating SVI values produces reliable and reproducible results that can be repeated under the same computing conditions. Such a level of precision and constancy of values confirms that the model is not sensitive to sample variations and can be used for comparisons across different regions and time periods. This confirms the Smart Village Index as a digitally verified, stable, and methodologically rigorous instrument, capable of quantifying the digital readiness and development potential of rural and touristic communities in a scientifically valid and technologically applicable manner.

Table 12.

Bootstrap stability test results.

These results also confirm the classification of rural communities into smart, transitional, and traditional villages, obtained in previous analyses, which verified the consistency of the SVI model through different analytical approaches. In this way, Python-based procedures confirmed that the Smart Village Index not only identifies but also algorithmically classifies types of rural communities, further proving its technical validity and functionality as a digital tool.

5. Discussion

The findings of the research helped to prove that the newly created Smart Village Index (SVI) is a valid analytical instrument that allows for the measurement of the readiness of rural communities for digital transformation in multiple dimensions with high reliability. This research has empirically confirmed that the modified Smart Village Index (SVI) is not only a theoretical analytical framework, but a digital–technological tool that allows for the measurement of the digital readiness of rural communities through the application of algorithmic and computer procedures. The SVI model is conceived as a technological–analytical system that integrates quantitative data from digital databases, automatically processes them through Python-based algorithms (Z-score transformation, PCA, K-Means classification, Bootstrap validation), and generates computer-calculated values of digital maturity. This confirms that the SVI model goes beyond traditional socio-scientific frameworks and functions as a digital instrument that uses methods of data modeling, algorithmic standardization, and multidimensional analysis. The model not only measures the level of digital transformation of a village, but also simulates changes depending on the value of the input variables, thus representing an operational tool that can be used in real planning systems, GIS, or e-government platforms. This proved that the SVI has technological and application value, because it combines information technologies, statistical modeling, and institutional indicators into a unique digital framework for quantifying rural transformation.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) demonstrated that the smart development of the villages could be best characterized with the help of six interdependent dimensions namely ICT infrastructure and connectivity, digital governance and transparency, leadership and local competence, community participation and social capital, sustainable economy and rural development, and infrastructure and quality of life. These results indicate that the process of digital transformation of rural territories is not a straight line, the boundaries of which are only technology, but a multi-level phenomenon where institutions and social aspects play a role.

Accordingly, the received findings can be regarded as an answer to the first research question: what dimensions are best used to describe the structure of a smart village and help to prove that the integration of technological, managerial, and socioeconomic factors is a precondition of its implementation? A comparative analysis of the ten rural communities studied showed that there were huge variations in the degree of digital maturity and thus gave an answer to the second research question—what factors have the most impact on the extent of digital maturity of rural communities? Cities like Aranđelovac, Kanjiža, and Titel had the largest values of the SVI, which demonstrates that the greatest level of digital maturity is achieved in the case of a balanced mix of developed ICT infrastructure, institutional openness, and active social engagement. On the other hand, smaller towns like Knjaževac and Crna Trava have lower index rates, which prove that the narrowness of infrastructural capabilities and the lack of assistance for local institutions are the most significant barriers to the digital change. Fagadar et al. [8] and Li and Peng [26], in their studies about European rural communities, found that the synergies of local leadership and institutional support are the most influential factor of smart development.

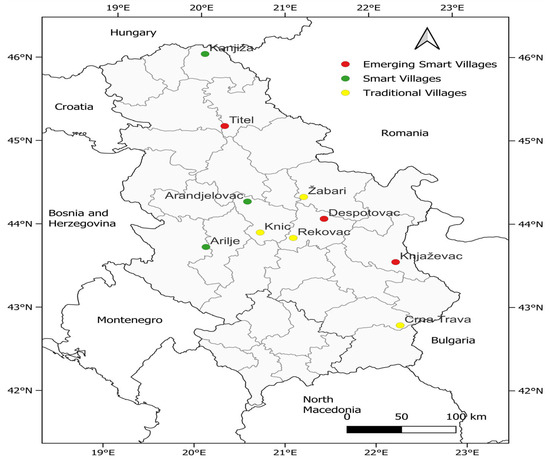

The spatial distribution presented in the map is a clear representation of the differentiation of rural municipalities in Serbia based on the values of the Smart Village Index (SVI). The findings suggest that Aranđelovac, Kanjiža, and Arilje are developed smart villages, Titel, Knjaževac, and Despotovac are emerging smart villages, and Knić, Rekovac, Žabari, and Crna Trava are traditional villages. This map validates the strong regional differences observed in this study, with the more digitally developed populations being clustered in the center and north of the Serbian territory, and the eastern and southern areas being less digitally mature (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Spatial classification of rural municipalities by Smart Village Index (SVI). The map was developed using QGIS 3.34 software, based on authors’ elaboration.

The received results show that the process of digitalizing the life in Serbian villages has a very uneven distribution on a territorial level, which answers the third question of the research, to what extent does the distribution of the level of digital maturity revolve around the regional differences? The areas of the country that are more administrative and technical, the north and the central regions of the country, record much higher index values compared with the southeastern and peripheral municipalities. The finding is consistent with that of Ali et al. [4] and Gerli et al. [14], who reported that the infrastructure and digital illiteracy disparity is highest in the weaker regions of Europe. Nevertheless, the institutional initiative of the local self-governments plays the decisive part in the Serbian context, as opposed to the technological infrastructure, which is the main determining factor in EU countries, a specificity that this study proved.

One of the values of this research is the empirical answer to the question of whether it is possible to create a nationally applicable model to evaluate digital maturity using solely official sources of statistical data. This study established, by using data from different institutional sources, that it is possible to create a methodologically coherent and statistically stable index using indicators that are objectively measurable. The strong reliability between factor scores and original indicators and the consistency of the results in sensitivity tests proved that insignificant differences in weighting do not affect index values and the allocation of municipalities. These findings coincide with the works of Xiao et al. [19] and Lyu et al. [29], who point out that effective models of smart villages should be empirically adjusted to the national situation. The difference, however, was that this study did not use a confirmatory approach (CFA), but rather an exploratory PCA, which is where a structure of the index is retrieved directly out of the data and there are no preconceived theoretical beliefs. This proves the uniqueness of the Smart Village Index model and its methodological strength.

Lastly, the discussion establishes that the process of the digital transformation of rural communities in Serbia is not a simple process, and it includes a combination of technological modernization, the adjustment of institutions, and social integration. The high level of interdependence between leadership potential, civic engagement, and investment in the ICT infrastructure backs the results by Ahmad et al. [33] and Ronzhin et al. [45] who, in their studies covering the rural setting, found that the success of smart villages is conditional on the proportion between technological resources and human potential. The resemblance of these results shows that the basic processes of the digital transformation of villages, despite any differences in the economical and institutional frameworks of analyzing contexts, are universal. Based on all on the findings, it suffices to conclude that the proposed Smart Village Index (SVI) is a feasible tool for the quantitative measurement of the digital maturity of the Serbian rural population. Not only does its structure enable classifying the villages into developed, emerging, and traditional ones, but it also gives empirical support to designing public policies, which will pursue more balanced and inclusive rural development. To be more exact, it provides a workable model that local self-governments will be able to utilize to plan digital strategies, budgets, and priorities in terms of infrastructural investment. Through this, the Smart Village Index (SVI) will be a tool that can directly assist in changing rural development management in Serbia.

6. Conclusions