User-Centric Design Methodology for mHealth Apps: The PainApp Paradigm for Chronic Pain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Background and Conceptualization

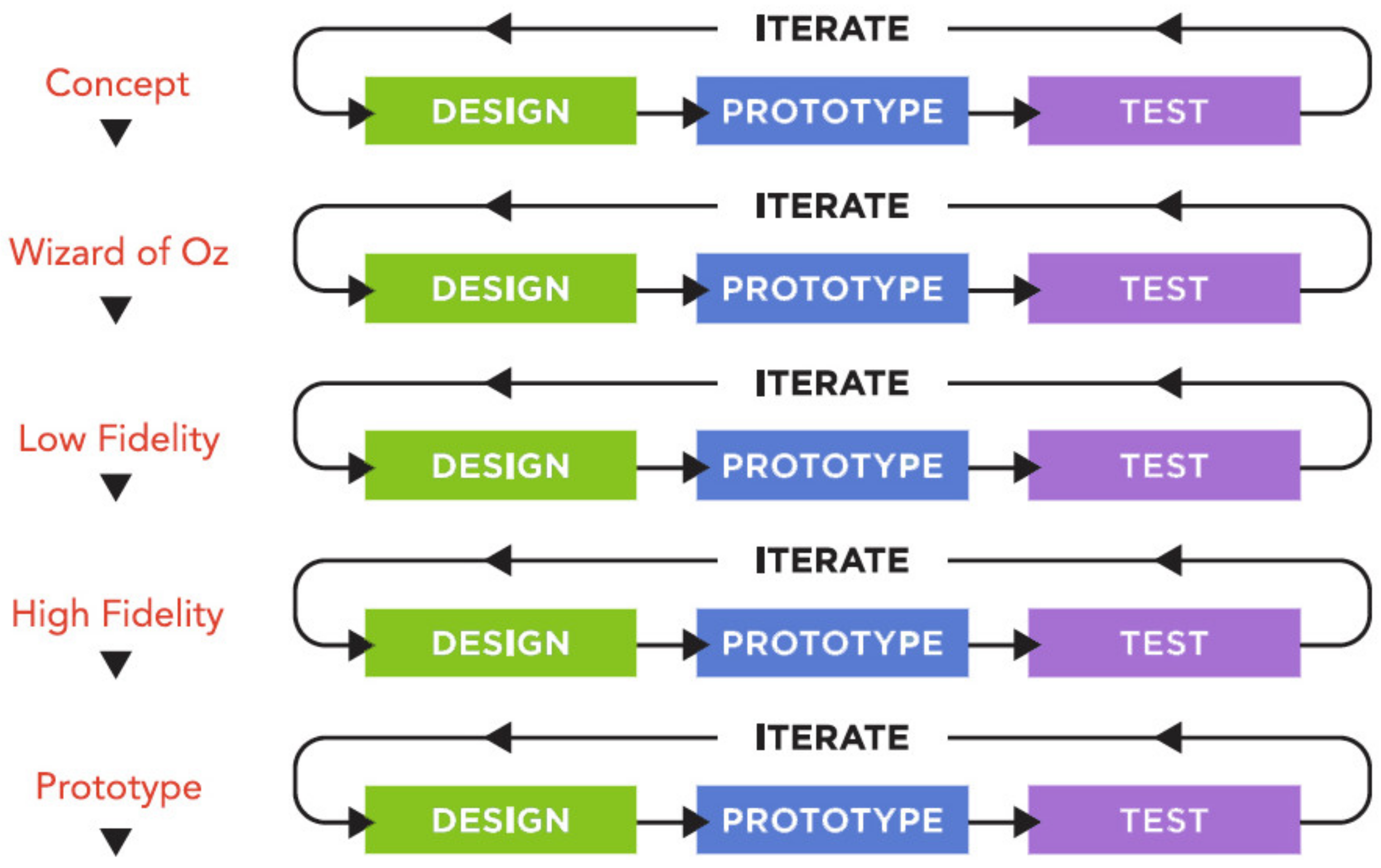

2.2. Phase 2: Alpha Testing

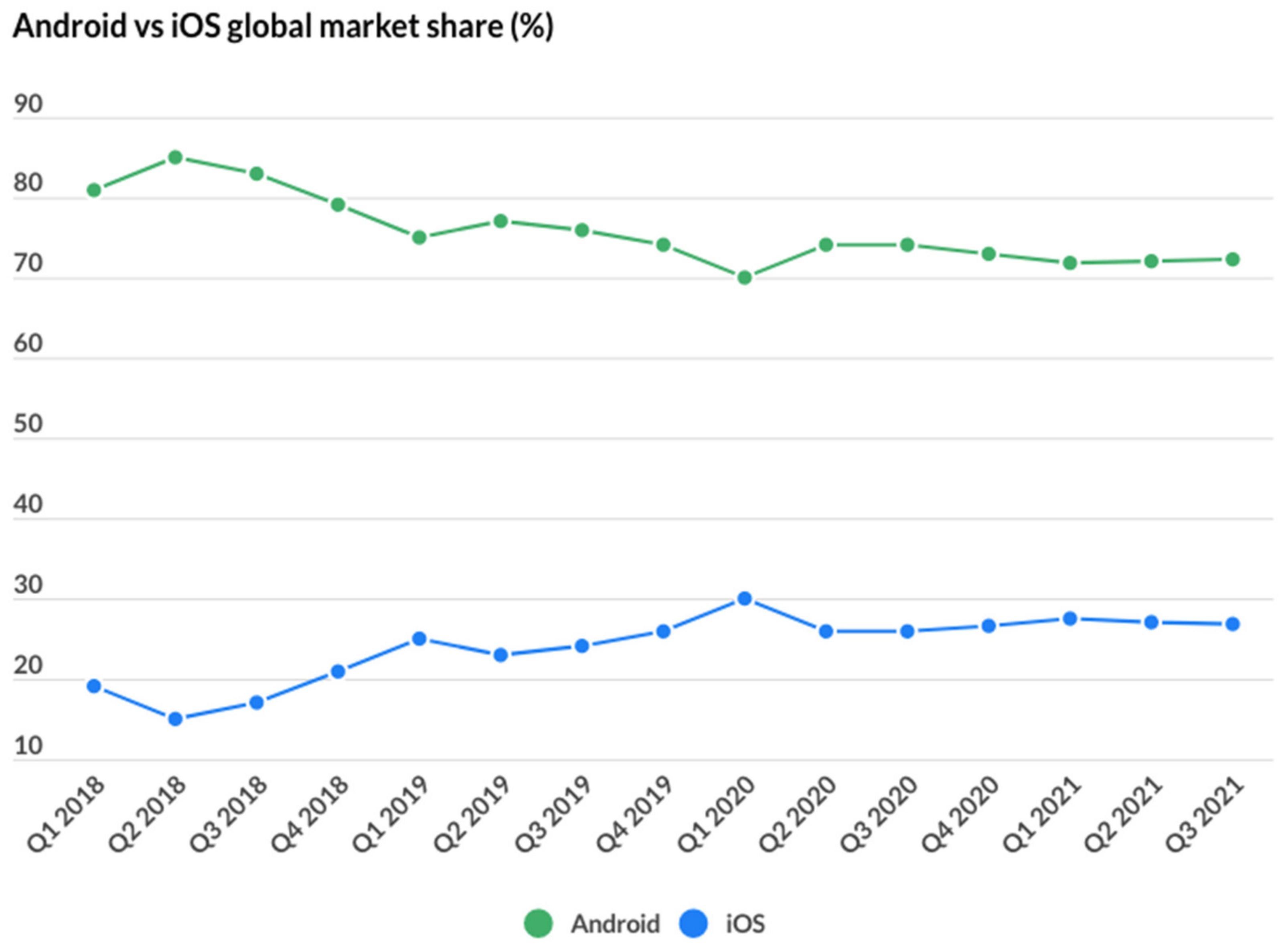

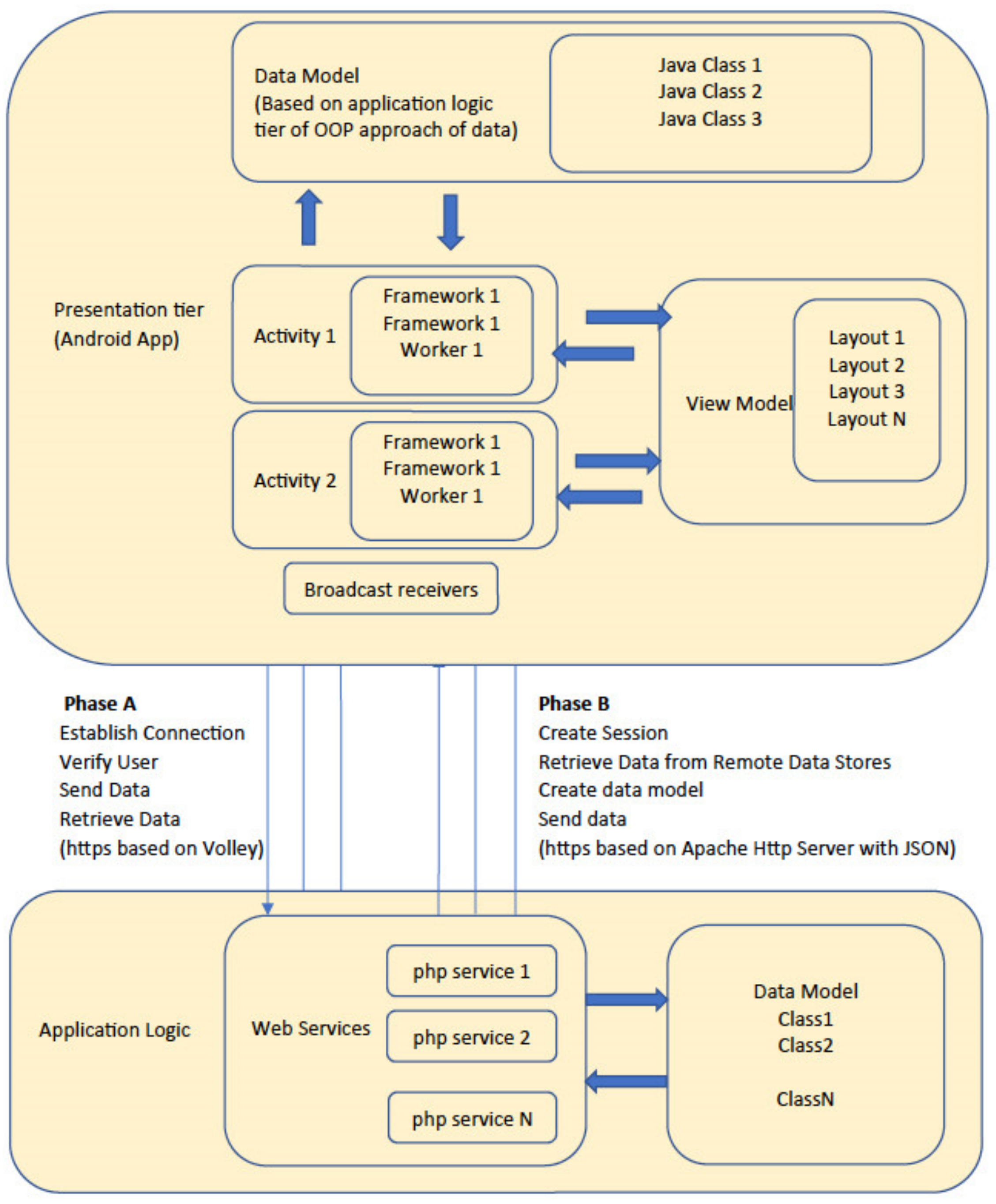

2.3. Phase 3: Software Development

2.4. Phase 4: Field Testing

3. Results

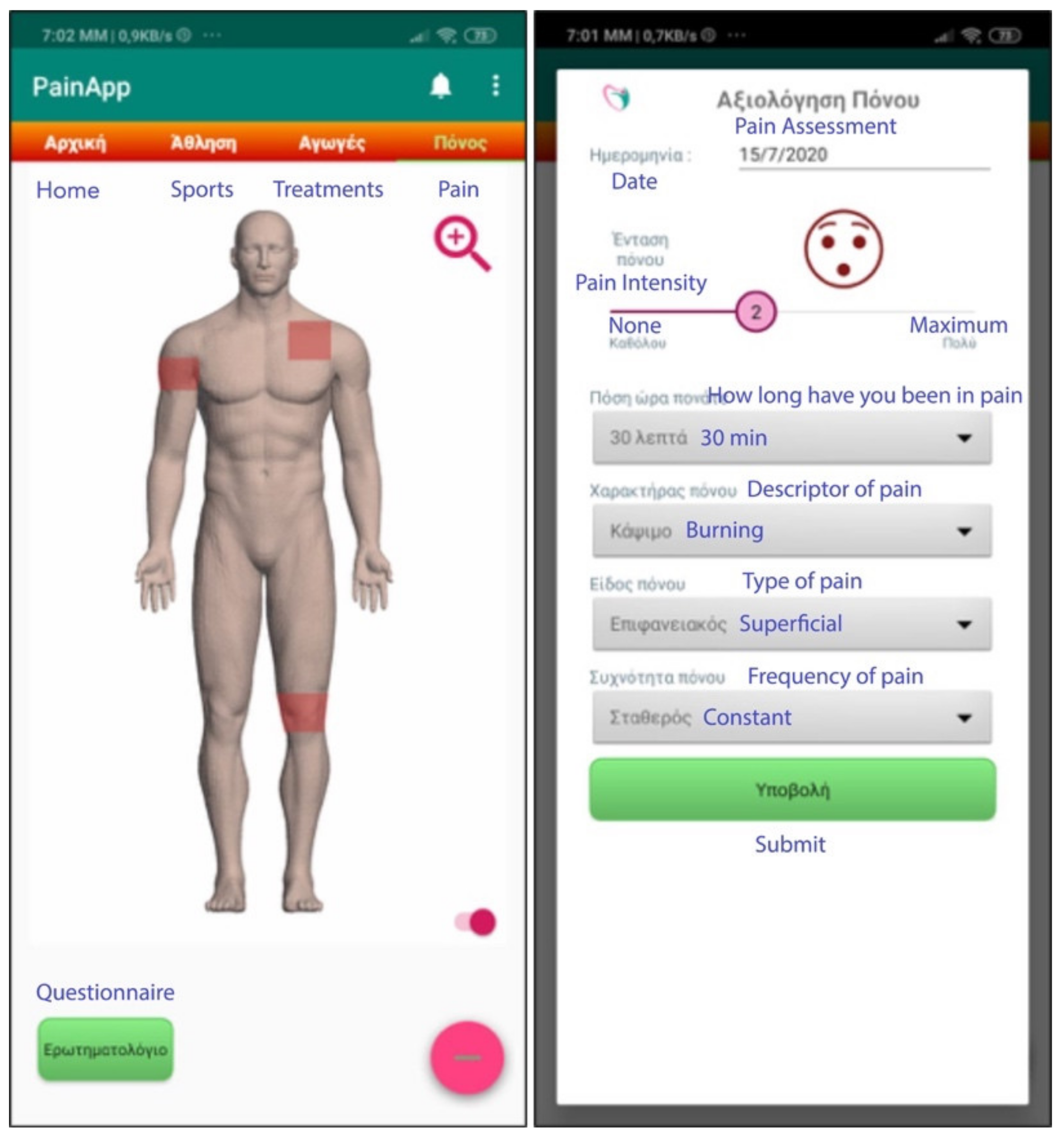

- Pain recording (body location, pain intensity, pain features);

- Consequences (domains affected);

- Pain treatment (medications and related scheduling);

- Pain assessment (medication vs. pain relief);

- Physiological parameters (age, sex, height, weight, body mass index);

- Underlying diseases;

- Lifestyle (habits, physical exercise);

- Alarms;

- History;

- Other functionalities (Login, Registration, Settings).

- Pain recording

- (i)

- What are the symptoms due to pain (e.g., nausea, dizziness, memory loss, etc.)?

- (ii)

- If the pain is accompanied by an event in the last 15 days (e.g., tension in the family or friendly environment, financial problems, weather changes, depression, starting an activity or sport, etc.).

- (iii)

- If the pain affected any daily activities (e.g., self-care, socializing, sleeping, housework, work, etc.).

- 2.

- Pain treatment

- (i)

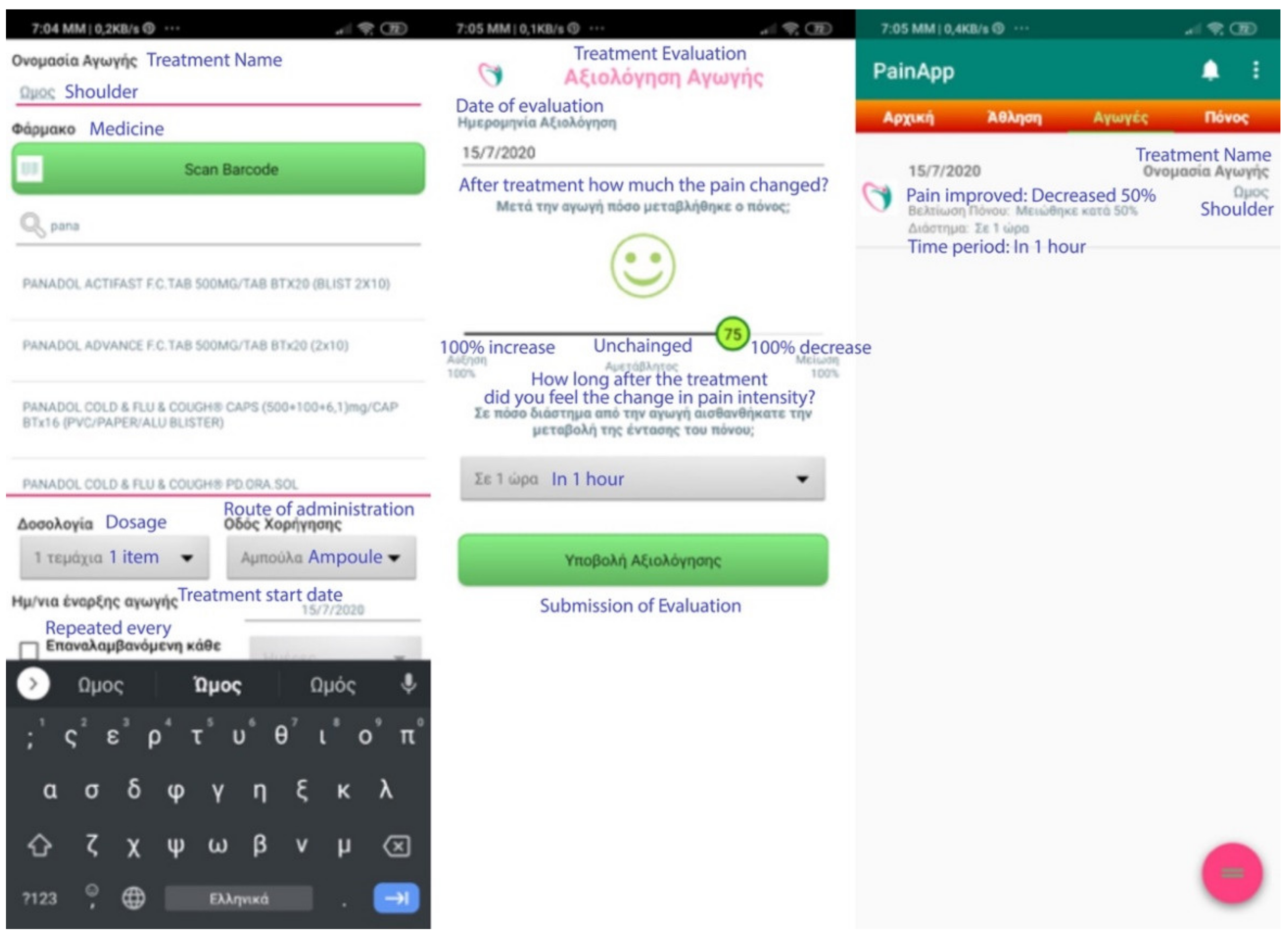

- When registering a treatment, he/she may choose to give an easy name to the treatment (e.g., shoulder, for a treatment involving a shoulder problem). One can start typing the name of the medicine or alternatively press the “Scan Barcode” button and scan the barcode on the medicine box with the camera of his/her mobile phone. The name of the drug is automatically registered and proceeds to declare the dosage, the route of administration (e.g., capsule, ampoule, injection, etc.), and the start date of the treatment. The user is also allowed to enter notes or make this treatment repeated (e.g., repeated monthly chemotherapy, daily treatments for orthopedic problems or cardiovascular disease, etc.).

- (ii)

- When evaluating the treatment/medication, the user can state whether the pain has changed (if it got worse or better and by how much), and for how long since he/she received the specific treatment. Again, the current date is automatically assigned as the evaluation date, but one can change it.

- 3.

- Underlying diseases

- 4.

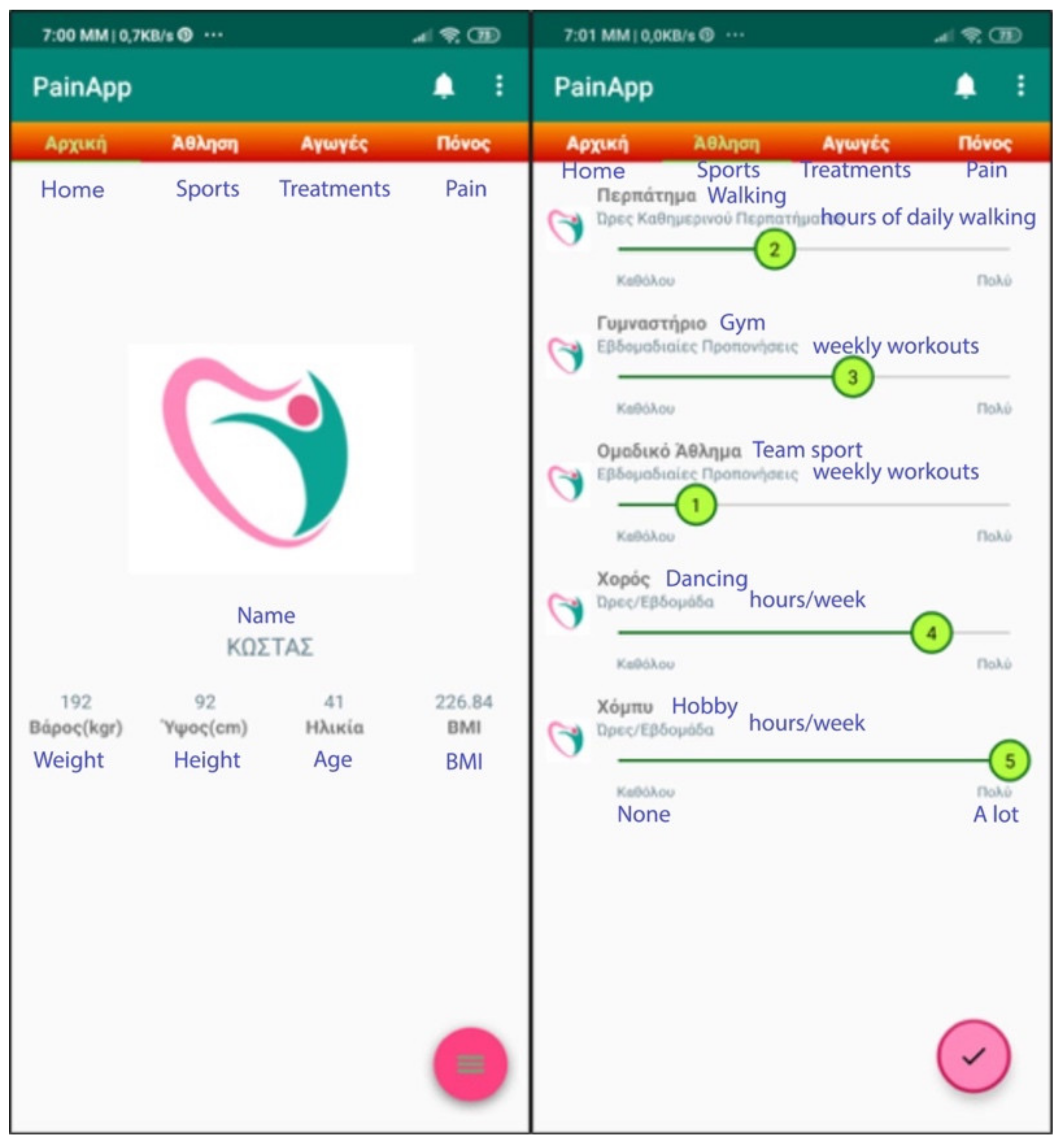

- Profile and Lifestyle activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merskey, H.; Bogduk, N. Classification of Chronic Pain, 2nd ed.; IASP Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1994; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PAHO. Leading Causes of Mortality and Health Loss at the Regional, Subregional, and Country Levels in the Region of the Americas, 2000–2019; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- SIP Platform. Impact of Pain on Society Costs the EU Up to 441 Billion Euros Annually. Societal Impact of Pain (SIP). 2017. Available online: https://www.sip-platform.eu/press-area/article/impact-of-pain-on-society-costs-the-eu-up-to-441-billion-euros-annually (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Working Group. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics 2019. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Koleva, D. Pain in primary care: An Italian survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 15, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäntyselkä, P.; Kumpusalo, E.; Ahonen, R.; Kumpusalo, A.; Kauhanen, J.; Viinamäki, H.; Halonen, P.; Takala, J. Pain as a reason to visit the doctor: A study in Finnish primary health care. Pain 2001, 89, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Data Research UK. Available online: https://www.hdruk.ac.uk/helping-with-health-data/health-data-research-hubs/alleviate/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- WHO. mHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies, Global Observatory for eHealth Series—Volume 3; World Health Organization: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; ISBN 9789241564250. [Google Scholar]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Georgoulas, A. A systematic review of mhealth funded R&D activities in EU. Trends, technologies and obstacles. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2020, 45, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser, B.; Eccleston, C. Smartphone applications for pain management. J. Telemed. Telecare 2011, 17, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalloo, C.; Jibb, L.A.; Rivera, J.; Agarwal, A.; Stinson, J.N. There’s a Pain App for That: Review of patient-targeted smartphone applications for pain management. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoldson, C.; Stones, C.; Allsop, M.; Gardner, P.; Bennett, M.I.; Closs, S.J.; Jones, R.; Knapp, P. Assessing the quality and usability of smartphone apps for pain self-management. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ossebaard, H.C.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, L. eHealth and quality in health care: Implementation time. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2016, 28, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthew-Maich, N.; Harris, L.; Ploeg, J.; Markle-Reid, M.; Valaitis, R.; Ibrahim, S.; Gafni, A.; Isaacs, S. Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Mobile Health Technologies for Managing Chronic Conditions in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibb, L.A.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Nathan, P.C.; Seto, E.; Stevens, B.J.; Nguyen, C.; Stinson, J.N. Development of a mHealth real-time pain self-management app for adolescents with cancer: An iterative usability testing study. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Belt, T.H.; Engelen, L.J.; Berben, S.A.; Schoonhoven, L. Definition of Health 2.0 and Medicine 2.0: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Medicine 2.0: Social networking, collaboration, participation, apomediation, and openness. J. Med. Internet Res. 2008, 10, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansky, K.H.; Thompson, D.; Sanner, T. A framework for evaluating eHealth research. Eval. Program Plan. 2006, 29, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, M.M.; Kuljis, J.; Papazafeiropoulou, A.; Stergioulas, L.K. An evaluation framework for Health Information Systems: Human, organization and technology-fit factors (HOT-fit). Int. J. Med. Inform. 2008, 77, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.; Nijland, N.; van Limburg, M.; Ossebaard, H.; Kelders, S.; Eysenbach, G.; Seydel, E. A Holistic Framework to Improve the Uptake and Impact of eHealth Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicolini, G.; Simonetti, V.; Comparcini, D.; Celiberti, I.; Di Nicola, M.; Capasso, L.; Flacco, M.; Bucci, M.; Mezzetti, A.; Manzoli, L. Efficacy of a nurse-led email reminder program for cardiovascular prevention risk reduction in hypertensive patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, H.; Campbell, J.M.; Stinson, J.N.; Burley, M.M.; Briggs, A.M. End User and Implementer Experiences of mHealth Technologies for Noncommunicable Chronic Disease Management in Young Adults: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trettin, B.; Danbjørg, D.; Andersen, F.; Feldman, S.; Agerskov, H. Development of an mHealth App for Patients with Psoriasis Undergoing Biological Treatment: Participatory Design Study. JMIR Dermatol. 2021, 4, e26673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Georgoulas, A. The Rise of mHealth Research in Europe: A Macroscopic Analysis of EC-Funded Projects of the Last Decade. In Mobile Health Applications for Quality Healthcare Delivery; IGI Global Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koumpouros, Y. The role of informatics and digital applications in chronic pain treatment. Tomorrow’s health, today: Patient Centered Care and Digital Technology. In Proceedings of the Agora Platform Annual Conference, Podgorica, Montenegro, 25–26 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Pappa, A. An mHealth tool for shared decision making for patients with rheumatism and arthritis. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR 2020), Frankfurt, Germany, 3–6 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schnal, R.; Roja, M.; Bakke, S.; Brow, W.; Carballo-Diegue, A.; Carry, M.; Gelaude, D.; Mosley, J.P.; Travers, J. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health (mHealth) applications (apps). J. Biomed. Inform. 2016, 60, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, K.E.; Lahir, S.; Brown, K.E. Targeting parents for childhood weight management: Development of a theory-driven and user-centered healthy eating app. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iribarren, S.; Akande, T.; Kamp, K.; Barry, D.; Kader, Y.; Suelzer, E. Effectiveness of Mobile Apps to Promote Health and Manage Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e21563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interaction Design Foundation. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Lowdermilk, T. User-Centered Design; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnum, C. Usability Testing Essentials, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agile Alliance. Available online: https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Scrum.org. Available online: https://www.scrum.org/resources/what-is-scrum (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Kanban Tool. Available online: https://kanbantool.com/kanban-software-development (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Sherman, R.; Imhoff, C. Business Intelligence Guidebook; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Berridge, E. Customer Obsessed: A Whole Company Approach to Delivering Exceptional Customer Experiences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Suman, R.; Sahibuddin, S. User Acceptance Testing in Mobile Health Applications: An overview and the Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Systems (ICISS 2019), Tokyo, Japan, 16–19 March 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pindeh, N.; Mohd Suki, N.; Mohd Suki, N. User Acceptance on Mobile Apps as an Effective Medium to Learn Kadazandusun Language. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Limpo, T.; Castro, S.L. Acceptance of Mobile Health Applications: Examining Key Determinants and Moderators. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, F.; Jacobs, M.; Pather, S. Barriers for User Acceptance of Mobile Health Applications for Diabetic Patients: Applying the UTAUT Model. In Responsible Design, Implementation and Use of Information and Communication Technology, Proceedings of the 19th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society—I3E 2020, Skukuza, South Africa, 6–8 April 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Hattingh, M., Matthee, M., Smuts, H., Pappas, I., Dwivedi, Y.K., Mäntymäki, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pagliari, C. Design and evaluation in eHealth: Challenges and implications for an interdisciplinary field. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, A.; Green, C.J. Beyond effectiveness: The evaluation of information systems using A Comprehensive Health Technology Assessment Framework. Comput. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P.; Mountain, G.; Black, N.; Nugent, C.; Zheng, H.; Davies, R. Knowledge transfer for technology based interventions: Collaboration, development and evaluation. Technol. Disabil. 2012, 24, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Wheeler, S.; Tavares, C.; Jones, R. How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: An overview, with example from eCAALYX. Biomed. Eng. Online 2011, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephan, L.S.; Dytz Almeida, E.; Guimaraes, R.B.; Ley, A.G.; Mathias, R.G.; Assis, M.V.; Leiria, T.L. Processes and Recommendations for Creating mHealth Apps for Low-Income Populations. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.K.; Nguye, H.Q.; Wolpin, S. Designing and testing a web-based interface for self-monitoring of exercise and symptoms for older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2009, 27, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SSL.com. Available online: https://www.ssl.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Android Developers. Available online: https://developer.android.com/about/versions/10/privacy/changes (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Research2Guidance. mHealth Economics—How mHealth App Publishers Are Monetizing Their Apps. Available online: https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-how-mhealth-app-publishers-are-monetizing-their-apps (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Benes, R. Most Apps Get Deleted within a Week of Last Use. Insider Intelligence. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/most-apps-get-deleted-within-a-week (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Statista, Mobile App Categories with Highest Uninstall Rate 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/892975/highest-uninstall-rate-app-categories (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Baumel, A.; Muench, F.; Edan, S.; Kane, J.M. Objective User Engagement with Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, M.; Sawyer, T.; Harris, M.; Skalka, C. Usability Evaluation of a Mobile Monitoring System to Assess Symptoms After a Traumatic Injury: A Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR Mental Health 2016, 3, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, G.; Dowdall, G.; Burls, A.; Perry, I.J.; Curran, N. Exploring the usability of a mobile app for adolescent obesity management. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2014, 2, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Weerdmeester, B.A., McClelland, A.L., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Chyjek, K.; Farag, S.; Chen, K.T. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS Scoring System. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, B.; Hickey, E.; Patel, M.G.; Mitchell, C. Quality assessment of a sample of mobile app-based health behavior change interventions using a tool based on the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence behavior change guidance. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, E.E.; Teo, A.K.S.; Goh, S.X.L.; Chew, L.; Yap, K.Y. MedAd-AppQ: A quality assessment tool for medication adherence apps on iOS and android platforms. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2018, 14, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFilippo, K.N.; Huang, W.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.M.; Eckhoff, R.; Nezami, B. A new tool for nutrition App Quality Evaluation (AQEL): Development, Validation, and Reliability Testing. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loy, J.S.; Ali, E.E.; Yap, K.Y. Quality assessment of medical apps that target medication-related problems. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2016, 22, 1124–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Kim, J. Development and evaluation of an evaluation tool for healthcare smartphone applications. Telemed. J. e-Health 2015, 21, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, S.; Ouyang, J.; Mimnagh, C. Effective? Engaging? Secure? Applying the ORCHA-24 framework to evaluate apps for chronic insomnia disorder. Evid.-Based Mental Health 2017, 20, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Zelenko, O.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Mani, M. Mobile app rating scale: A new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koumpouros, Y. A Systematic Review on Existing Measures for the Subjective Assessment of Rehabilitation and Assistive Robot Devices. J. Healthc. Eng. 2016, 2016, 1048964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Auer, K.; Miller, R. Extreme Programming Applied; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dildine, T.C.; Necka, E.A.; Atlas, L.Y. Confidence in subjective pain is predicted by reaction time during decision making. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghill, R.C. Individual differences in the subjective experience of pain: New insights into mechanisms and models. Headache 2010, 50, 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicholas, J.; Shilton, K.; Schueller, S.M.; Gray, E.L.; Kwasny, M.J.; Mohr, D.C. The Role of Data Type and Recipient in Individuals’ Perspectives on Sharing Passively Collected Smartphone Data for Mental Health: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Burgess, E.R.; Reddy, M.C.; Rothrock, N.E.; Bhatt, S.; Rasmussen, L.V.; Butt, Z.; Starren, J.B. Provider perspectives on the integration of patient-reported outcomes in an electronic health record. JAMIA Open 2019, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, A.; Bolser, B.; Crocker, J.; Miller, J.; Parman, C.C.; Warner, D. Managing Unsolicited Health Information in the Electronic Health Record. J. AHIMA 2013, 84, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

| Doctor Requirements | Patient Requirements | Items Included | Domains-Features | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Pain recording | P1. To record the point of pain very easily without having to type texts | D1, D2, D5, D9, D11, P1 | Pain recording: several locations may be pointed, duration of pain, intense of pain, type of pain. | A patient may feel pain in various parts of the body. All different points must be recorded. |

| D2. How long the pain lasts | P2. Should not require special knowledge for its use and should not be complicated | D4, P8, P9 | Treatment recording: name of medicine, time administered, frequency. | |

| D3. How long after the treatment did the pain decrease and to what extent | P3. Limited knowledge of using mobile phones | D3, D10, P9 | Treatment efficiency: if the treatment helped to reduce the pain, how long after the treatment did the pain decrease, how much did the pain decrease, for how long did the treatment work effectively. | |

| D4. What medication the patient is taking and how often | P4. Functions that help them in daily life | D6, D7 | Domains affected: work, daily life, socializing, psychological issues, etc. | Each pain point can have a different effect on the patient and his/her daily life. |

| D5. How and how intensely he/she feels the pain | P5. No labyrinthine menus | D6, D8 | Other possible causes of pain: new routine, sports, weather, etc. | Many of these can happen in parallel. |

| D6. Pain has affected other activities in the patient’s daily life | P6. Do not know English or the official names of the drugs | P2, P3, P5, P7, P10 | User Interface: easy to use, not many texts, use of images, not many sub-menus, etc. | Better to use images and sliders were possible. Not long texts. Simple wording. |

| D7. Pain has created other problems in the patient such as depression, stress, etc. | P7. Simple and understandable text even by users with a low level of education | D10, P4, P6, P8, P10 | Usability: alarms and notifications, drop down lists, scanning functionality. | Notifications for repeated treatments and reminders to evaluate their effectiveness. Scan drugs and choose disease from a list. Very limited typing. |

| D8. Are there some other conditions that the patient suspects are the cause of the pain he/she is feeling? | P8. Treatments and medications may be repetitive | |||

| D9. The pain is permanent or transient | P9. Treatment has helped in pain relief (to what extent and after how long) | |||

| D10. The patient feels that the particular treatment has helped him/her | P10. Add simplistic descriptions | |||

| D11. How the pain is felt | ||||

| D12. Access history data |

| Barrier | Methodology | PainApp Approach 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Not clear interface | UX experts and behavioral scientists collaborated with many and different patients with diverse diseases. | Phase 1 → The interface provides only the necessary information considering issues such as low IT literacy. There are a limited number and basic menus without submenus. |

| Unmet expectations | Frequent meetings with health professionals and patients in order to detect and assess the needs. | Phase 1 → Initial recording of all functionalities asked. Prioritization from the end users in order to agree and keep only the “essential” ones. |

| Many bugs | Debugging in all phases. | Phase 2–4 → Continuous debugging was performed in each phase of the project with the active participation of all the different end users. The collected info was then grouped and the necessary actions were taken. |

| Lack of value | Specific problems should be addressed taking into account all requirements from different users. Generic assumptions and requirements should be avoided. | Phase 1–2 → Pain was the core target of the app. Doctors and patients were the only target groups. The solutions should not focus on specific diseases. Intervention flow was assessed at an early stage. |

| Notifications and communication strategy | Only important notifications should be given. | Phase 1–2 → Only notifications regarding assessment of scheduled treatments was provided. |

| Content | Content should be valid and updated as needed. | Phase 1–2 → Only patients can add content. So, its validity is guaranteed. No need for updates from other sources. |

| Learning curve | Intuitive interface. | Phase 1–4 → Graphics are clean and used appropriately only when providing value. Following the principle of simplicity, no confusing content or graphics have been added without providing real value to the user. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koumpouros, Y. User-Centric Design Methodology for mHealth Apps: The PainApp Paradigm for Chronic Pain. Technologies 2022, 10, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010025

Koumpouros Y. User-Centric Design Methodology for mHealth Apps: The PainApp Paradigm for Chronic Pain. Technologies. 2022; 10(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoumpouros, Yiannis. 2022. "User-Centric Design Methodology for mHealth Apps: The PainApp Paradigm for Chronic Pain" Technologies 10, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010025

APA StyleKoumpouros, Y. (2022). User-Centric Design Methodology for mHealth Apps: The PainApp Paradigm for Chronic Pain. Technologies, 10(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010025