1. Introduction

Lobbying, of any type, is always used for acquiring some political advantage in the United States (US). Even the Congressional historical records have stated that the American Revolutionary veteran groups lobbied the Congress during the 1790s, which was much before any primary lobbying-related regulations were implemented in 1876 (

Byrd 1991). Currently, the growth and the scale of the lobbying practices are very substantial. In the USA, the political campaign costs have increased significantly. The report submitted by The Centre for Responsive Politics (

https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/) stated that the lobbying costs that were spent by the various organisations in 2016 were >

$3.2 billion, where the Top-5 firms were responsible for 40% of the overall costs. Amongst the Top-5 companies, Gump et al. spent ≥

$36 million, followed by the Podesta Group (

$24 million), Van Scoyoc Associates (

$21 million), Holland and Knight (

$19 million), and the Squire Patton Boggs (

$18 million). Many organisations partake in lobbying. In comparison to the alternative techniques of seeking a political influence, like the contributions made by the corporate Political Action Committees (PACs), many organisations used the lobbying activities to acquire a political advantage (

Chen et al. 2015). The corporate lobbying involves the various political activities that are employed by the corporations to influence the legislators at different governmental levels. At the federal level, the corporate lobbying includes any form of communication which is made on the behalf of the client to the various members of the Congress, like the staffers, White House staff, The President, or other high-level employees regarding the modification, formulation, or the adoption of any legislative decision (The Centre for Public Integrity).

1 This was controlled by the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995.

Many economists have stated that the firms that lobbied for political connections could acquire many economic benefits (

Roberts 1990;

Stratmann 2005;

Fisman 2001;

Jayachandran 2006;

Faccio and Parsley 2009;

Hochberg et al. 2009;

Igan et al. 2009;

Richter et al. 2009;

Cooper et al. 2010;

Yu and Yu 2011;

Hill et al. 2013). Also,

Richter et al. (

2009) suggested that an important factor that led to corporate lobbying included the desire to acquire subsidies for the R and D sector, which was considered to be a very risky investment when compared to the capital investment. Earlier studies indicated that engaging in any political process could act as insurance against the economic crisis.

Faccio et al. (

2006) noted that the firms that had a political connection in 35 countries were very likely to derive government bailouts during economic distress as compared to the non-connected organisations. The rationale behind this observation was that, since the government actions and regulations directly affected the company’s business condition, political lobbying could help the companies to derive important information regarding the regulatory agenda, acquire political information for altering their business decisions in time, and encourage (or discourage) the regulatory decisions that could be beneficial (or detrimental) to the company, if possible. Due to regular communication, this information helps the government make better decisions. However, corporate lobbying acts as an instrument by the organisations for interfering in the policy formation process, which directly affects the lobbying interests. For instance, the various companies involved in the controversies, scandals, or lawsuits (like Phillip Morris, WorldCom, Enron, and Halliburton) had spent a lot of money on lobbying (

Chen et al. 2015).

It is very surprising that the various empirical studies ignored the effect of corporate lobbying on the financial performance of the organisation. Lobbying was seen to be the biggest type of political involvement in corporate America. With regards to its financial effect, corporate lobbying was 20-times higher than the PAC or the soft-money contribution made every election cycle. Furthermore, many corporations, business-related groups, or trade associations are responsible for the huge amount of money spent on lobbying. Many individual organisations also spend a lot of money every year. Additionally, many researchers, investigating the corporate political activities, have investigated the different types of expenditures by the corporate-affiliated PACs. This also involved the problem of limited variation and a narrow political activity, i.e., sponsorship of the PACs (

Andres 1985;

Masters and Keim 1985;

Grier and Munger 1991;

Grier et al. 1994;

Humphries 1991;

McKeown 1994;

Mitchell et al. 1997). In their study,

Milyo et al. (

2000) described the “inordinate attention to the PACs”, by stating that the data regarding the contribution was available and the PACs could be linked easily to their industrial or corporate sponsors. Furthermore, Sabato (

Morris and Sabato 1984) noted that the PACs are formed by the groups that are not capable of establishing a governmental affair or a legislative lobbying department. On the other hand, many companies have a good lobbying division and no PAC.

Brasher and Lowery (

2006) warned that this type of investigation was narrow and suggested that the empirical studies regarding the PAC behaviour could not be generalised, but they should have focused more on corporate lobbying.

Ansolabehere et al. (

2003) observed that the major distinction was that since the PAC finances are because of individual contributions and not by corporations, the PAC expenditure cannot be considered as ‘corporate’. However, corporate lobbying is considered to be a corporate expense, which helps in improving the firm’s performance. Hence, many corporations indulge in corporate lobbying. Similar to the alternative techniques of acquiring political influence, like the PAC contribution, lobbying is another popular method that is used by the corporations for exercising the political strategies (

Chen et al. 2015). Based on these parameters, in this study, we have focused on the effect of the corporate lobbying on the financial performance of the corporations.

Here, we have also determined the dominating effect amongst the above-mentioned countervailing forces, and the circumstances surrounding it. Firstly, we have analysed the corporate lobbying expenses and compared them to the PAC contributions. We attempted to determine the causal effects of the corporate lobbying on the Corporate Financial Performance (CFP). We analysed all of the firms from which they could obtain the financial data, including many firms that were not very politically active. This helped us to derive the benefits from the data’s panel structure, which helped us further control the various time-invariant and firm-specific variables after we had compared the firms that lobbied and those that did not. A few researchers (

Nichols 2007;

Angrist and Pischke 2010) stated that this technique was used for addressing the bias that occurred because of unobserved confounders, which were commonly seen in the studies that rely solely on the observational data. This study also used another identification strategy, wherein another moderating variable was introduced for examining the effect of the organisation’s slack on the association between the CFP and corporate lobbying. Here, we evaluated the impact of the lobbying activities on the CFP, while controlling the inherent endogeneity by using many alternative methods.

We have also postulated that the total costs (or benefits) of the corporate lobbying varied with regards to the organisational slack. The slack resources included the spare assets and the capabilities of the company, which could be reclaimable for the re-deployment. It also includes the hidden and underutilised spare resources that can be reused and recaptured for many tasks. Though several governmental policies and regulations affect the firms, the marginal advantage derived due to the lobbying activities can be determined by the different factors that affect the demand and supply of the firm’s products or services. Hence, every lobbying activity shows a different effect on the CFP. Very few studies used this approach. In this study, we examined the association between the corporate lobbying activities and the CFP based on organisational slack.

We used the data from various Fortune magazines’ American Most Admired Corporation (AMAC) firms for a 10-year period (2007–2016) and evaluated whether the corporate lobbying was advantageous to the shareholders. We also determined if the organisational slack controlled the association between the CFP and the corporate lobbying. This study showed no significant relationship between the CFP and the corporate lobbying activities. Furthermore, this neutral association could also be partially due to the fact that the lobbying expenditure by the company was unable to provide a few tangible benefits or helped the firm acquire additional governmental contracts and improved the probability of getting the bill passed in the Congress. This indicated that agency expenditure (i.e., an inefficient use of the corporate funds) for the lobbying activities dominated the strategic benefits of the lobbying. Secondly, we also noted the positive relationship between the lobbying activities and the organisational financial slack on the CFP that firms’ organisational slack acts as a moderator of the impacts of corporate lobbying on performance; firms that are efficient in utilizing their available resources will be able to register better links between corporate lobbying and firm performance.

These findings showed significant implications. Firstly, the results indicated that the lobbying costs were higher than the benefits, thereby supporting the agency’s perspective in comparison to the stewardship viewpoint. Secondly, the results highlighted the endogenous and dynamic nature of the association between the CFP and the lobbying activities. These results suggested that the control of the endogeneity was important for investigating the effect of the various lobbying activities. Thirdly, we noted that the impact of the lobbying activities was heterogeneous for the firms and that the moderating variable of organisational slack could enhance the relationship between the CFP and the lobbying activities.

The remaining paper is organised in the following manner:

Section 2 includes the literature review and the hypothesis development, whereas

Section 3 discusses all the acquired data and the methodology used.

Section 4 and

Section 5 describes and analyses all of the empirical results, while the discussions and conclusions are presented in

Section 6 and

Section 7.

6. Discussion

There has been an increasing interest in the lobbying and other political activities of the various organisations. Till date, the academics and the financial press have focused primarily on the weaker measure of the political activities, i.e., PAC contributions. However, the PAC contributions are a very small percentage of the total corporate political activities. Furthermore, as they are made by the individuals, they cannot be included as corporate expenses. This study has noted that the lobbying expenses are the biggest type of corporate political activity in America. This is determined by the number of the companies that are engaged and the amount of money spent. These factors showed that the lobbying activities were significantly higher than the corporate PACs and the soft money donations (banned). Therefore, this study used the publicly-accessible data about the corporate lobbying activities for investigating the financial effect of the corporate political activities.

This study examined the relationship between the CFP and the corporate lobbying activities with an aim to determine the moderating role of organisational slack. Many recent studies have indicated that the relationship between the corporate lobbying and the CFP was slightly positive, however, some researchers stated that further investigation was necessary for clarifying the role played by the omitted variables that could interfere in the relationship. This debate is still open and new models are required, which can address these issues. This study has tried to explain the lobbying activity interface after analysing the role played by organisational slack.

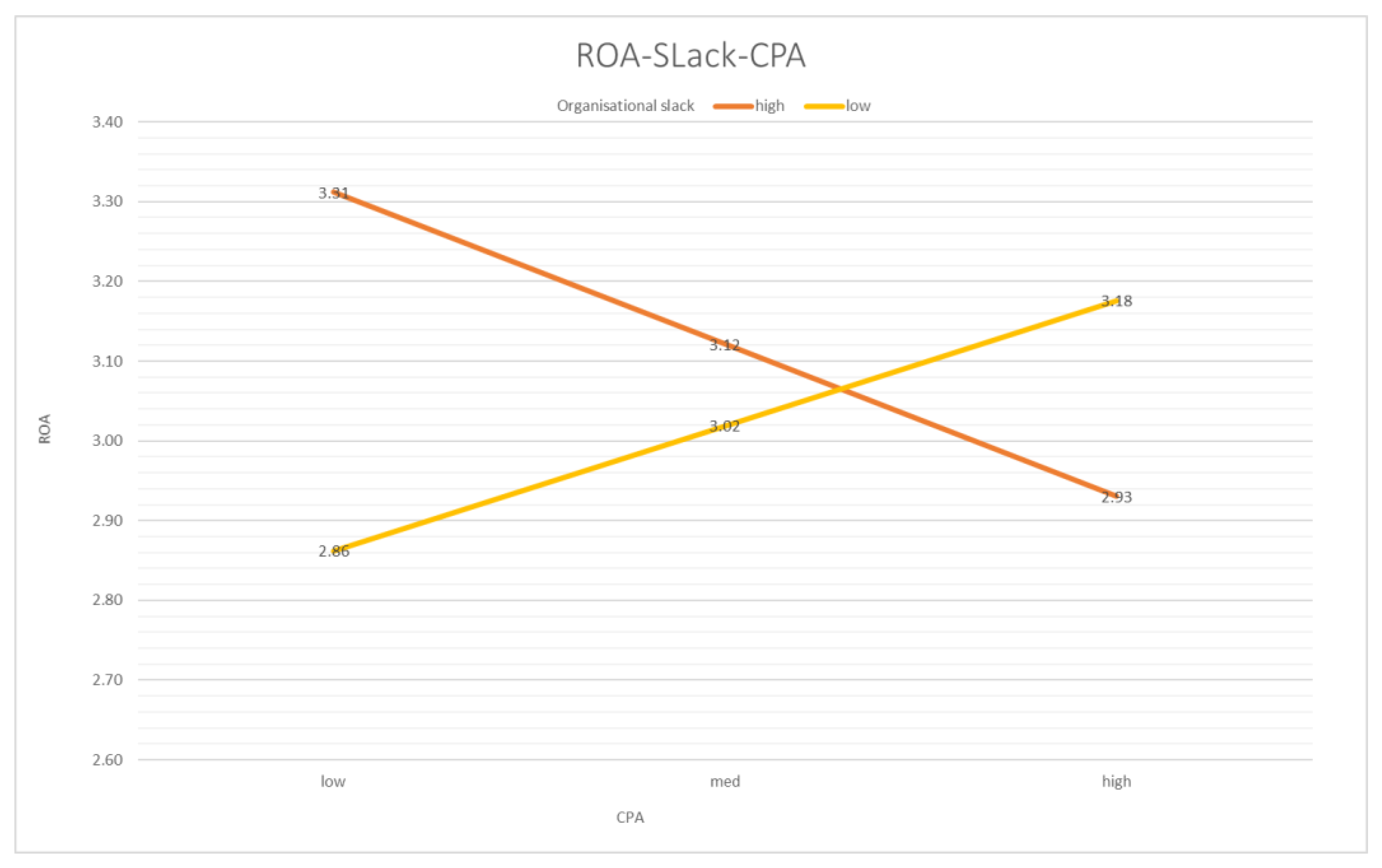

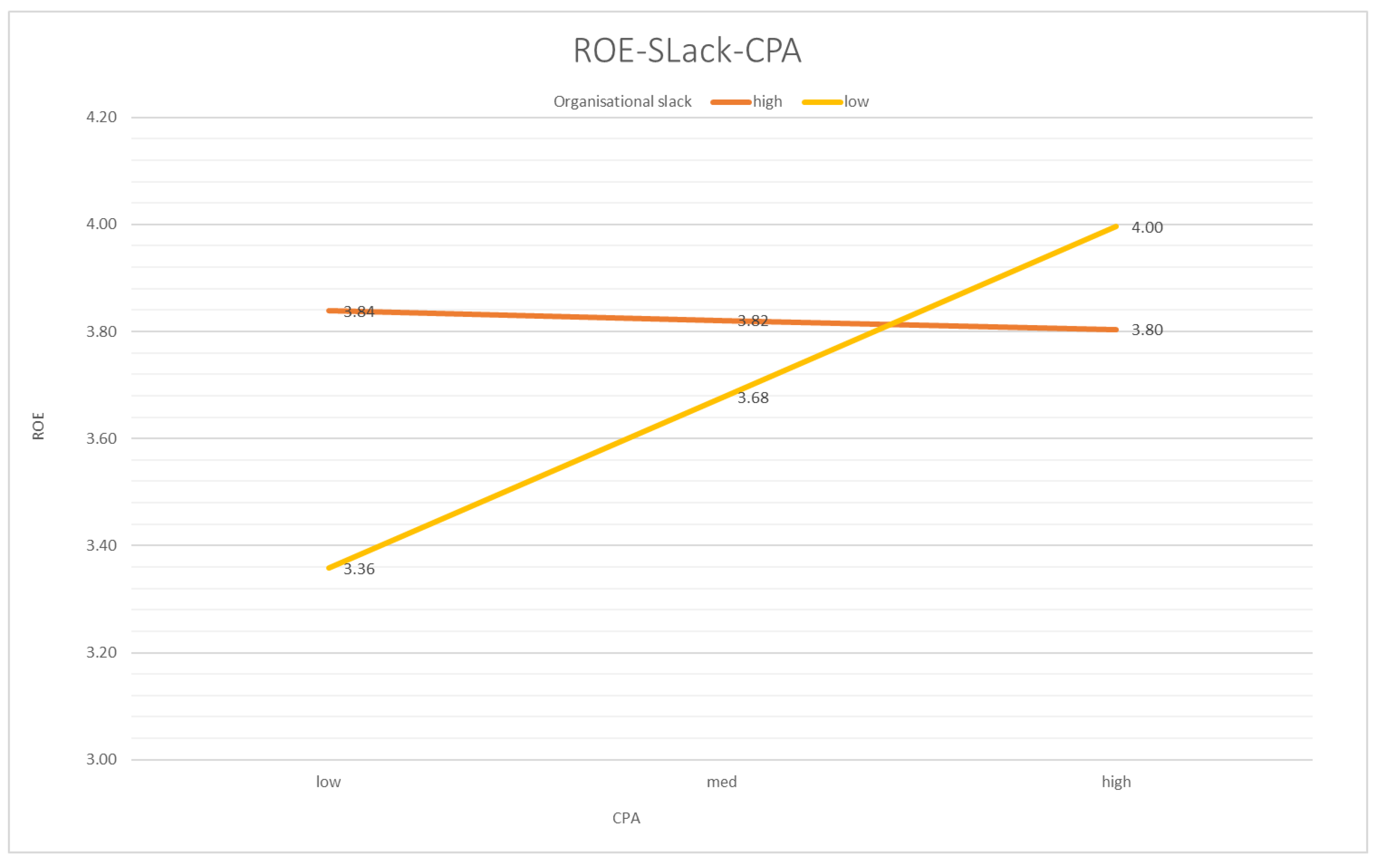

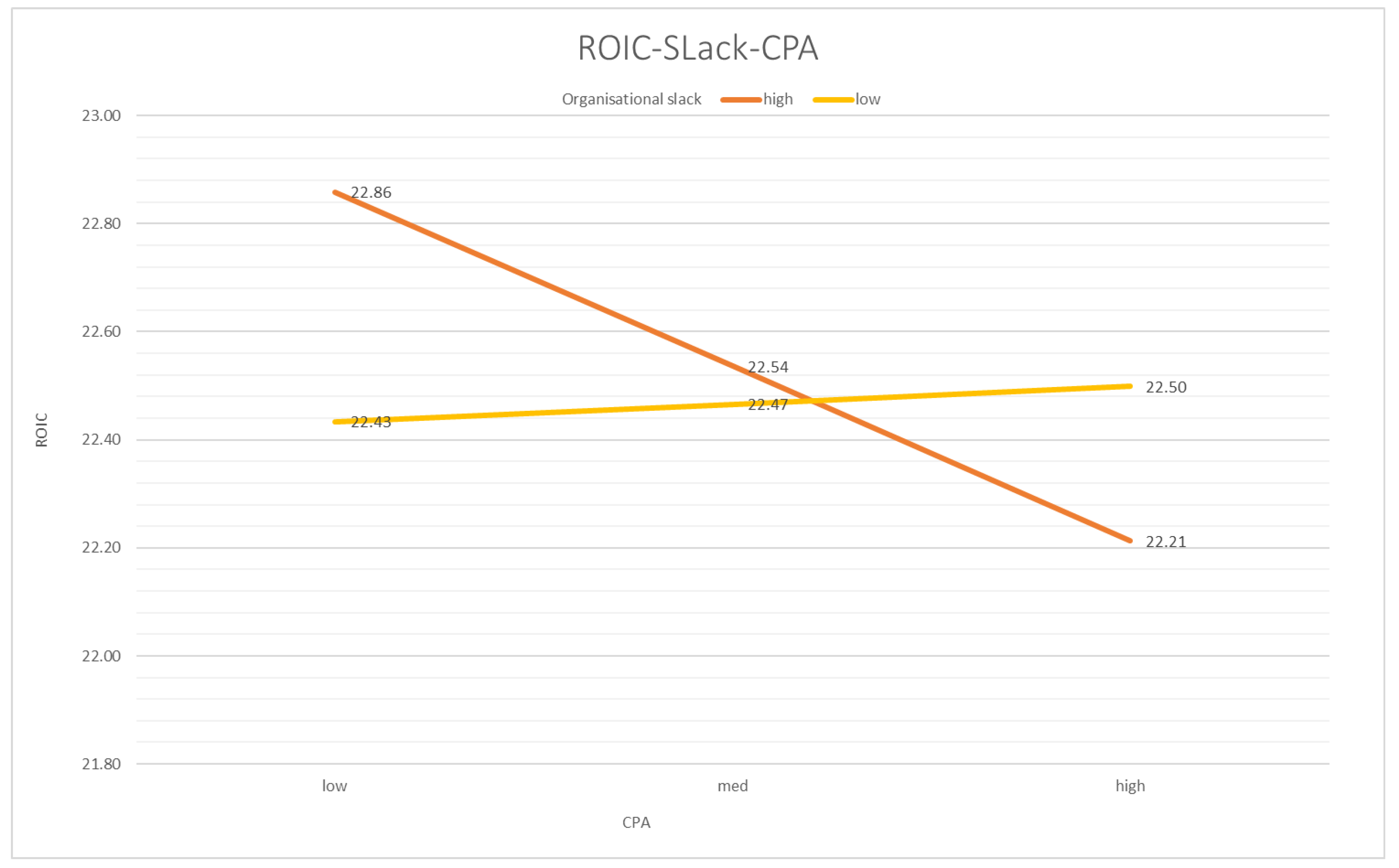

This study has presented several results describing the relationship between the corporate lobbying and the CFP. Firstly, while taking into consideration the dynamic data for the system-GMM estimation and regression, the researchers noted that the lobbying expenses were not significantly correlated with the CFP. Secondly, this study investigated the two-way interaction between the lobbying and the organisational slack, after using the CFP as a dependent variable. The results showed that organisational slack negatively interacts with the corporate lobbying, which indicates the synergy. Also, the interaction between the corporate lobbying and logistic slack generated a detrimental effect on the CFP, thereby rejecting H2. These results were robust to the different measures of the CFP, i.e., ROA or ROIC.

All of the results in this study have contributed to the theory in many ways. We noted that the corporate lobbying does not necessarily improve the CFP, which was explained using the political market theory, as it emphasised on the political competition, suggesting that the corporate lobbying activities could be an important component of the zero-sum political game, which cannot be accurately evaluated. This political marketplace theory regards corporate lobbying as an exchange in the policy arena that occurs between the policy demanders, like various interest groups or firms, on one hand, and the legislators, policy suppliers, regulators, etc. on the other hand (

Bonardi et al. 2006). Many firms compete with one another for limited access to public officials (

Hillman and Hitt 1999). Due to the increasing number of political rivals, the specific firms find it difficult to forward a particular public policy agenda successfully (

Hall and Wayman 1990;

Baumgartner et al. 2009). Similar results were noted by

Baumgartner et al. (

2009), who stated that the lobbying expenditure was not related to the public policy success. They also concluded that they could not observe any relationship between the resources and the policy results.

To explain further, though some managers believe that they can alter the political scenario, in actual reality, the firms cannot successfully predict the decisions of the policymakers, since policymaking involves personal, party, state, national, or media influences (

Keim 2001). This factor, along with the rational decisions of the corporate decision-makers, increases the strategic uncertainty related to the corporate lobbying or its ability to produce the desired outcome, like an improved CFP (

Hart 2010). Due to this uncertain influence, the corporate lobbying was seen to be less successful than what is presumed.

In this paper, we have extended the contingency theory to include corporate lobbying and the CFP. The contingency theory claims that external and internal factors have an impact on organisational structure and management. In this perspective, we applied this theory to demonstrate that corporate lobbying is highly situational determined firm performance and organisational slack as influential factor. The contingency theory has highlighted the significance of obtaining a fit or a congruency between the corporate lobbying and the level of organisational slack of the firm. The idea of organisational slack as an important driver of corporate lobbying originates from behavioural theory. As shown by this study, the amount of organisational benefits that can be obtained from corporate lobbying is contingent on the organisational slack when the resources level is low. Firms with low slack might see political activities as the only solution to rectify their financial woes (

Hillman et al. 2004). We argued that firms with limited organisational slack have the potential of increasing their profits through lobbying on public policy protection, for instance through high tariffs for imported goods using the “infant industry protection” argument, but do not have the purchasing power. The level of organisational slack of a firm may influence its decision to seek political favours. The lesser a firm is in slack, the more sensitive it is to government’s policies. Firms may seek political favor or intervention when trying to secure a government project and may ask for a subsidy.

Limitations and Future Research

Similar to other studies, this paper also has some limitations. Firstly, as the data used here was historical, the causalities could not be easily surmised. Though we have tested all of the equations within the model that showed a delayed effect on the political activity (reverse of the proposed hypothesis), they noted no evidence regarding this relationship. This raises a few questions regarding the causal relationships described in the empirical studies without experimentation. Secondly, since this field is very concentrated, the number of companies included was very small (N = 134). Though the estimations can be improved in this panel data set (N = 1294), increasing the sample size would be better. The future studies will have many techniques at their disposal for improving the published literature and determining the perfect category in which this study can be fit. This could be done by qualitatively studying the relationship that exists between the firm-level lobbying and the CFP. For instance, a massive case study can be carried out in many industries for expanding the scope of the corporate lobbying literature. This project would be empirical and also based on a theory. This phenomenon has not been researched in this area.