This section will present a critical discussion of the most important works conducted in banking regulation. From the literature review, it is identified that there is a gap in the stock market reaction of banks and insurance companies to the Banking Reform Act 2013. This section focuses on the first objective defined in the previous section. The strategic forces pushing government and financial institutes to impose more regulation in the economy are also evaluated. The topics of banking efficiency, diversification, performance, and risk absorbing are explored to better define the gap in the literature. In the last part, a discussion on the stock market reaction to regulatory act and reform are presented. At the end of this section, it is hoped that the reader is better informed in those areas with a critical understanding of the key issues presented and that a clear focus and justification will emerge for empirical research in this field.

Literature Review

The financial sector is one of the most heavily regulated sectors in the economy and the banking area is by far the most heavily regulated industry. The literature on bank regulatory practices is copious. Financial regulation and supervision are needed to protect the banking and financial system. Sometimes, the reasons for banking regulation are not clear from a theoretical prospective; two contrasting views emerging as explained more fully by

Barth et al. (

2006). The “public interest view,” as stated by

Barth et al. (

2013), sustained that the government regulates banks through the correction, or elimination, of market failure, such as monopoly or externalities with the ultimate intention of benefitting the public. From this perspective, a powerful supervisory agency that directly monitors and discipline banks can (a) reduce corruption and enhance the efficiency of capital allocation and (b) encourage a sufficient degree of competition to boost the efficiency of intermediation.

In contrast to traditional economic views, which maintain that stronger official supervision will increase bank performance and stability, the ineffective-hand view did not expect any improvement in terms of bank performance and stability (

Barth et al. 2006). The “private interest view” holds that regulation impedes bank efficiency because it is often used to promote the interest of the few without caring about the interest of the whole public (

Barth et al. 2013). This can happen, for example, when government regulates banks to facilitate the finance of the government expenditures to funnel credit to politically attractive ends, and in a more general way to maximize the welfare interest objective of politicians and bureaucrats. In this context, a more detailed argument in the literature emerges; this includes arguments from proponents and opponents of banking reforms. People belonging to the first philosophy feel that regulatory activities are important because it is necessary to restore confidence in the banking sector and improve credit system, and as a result, the economy will be less vulnerable to recession (

Hryckiewicz 2014). More importantly, proponents of regulatory intervention argue that such actions do not negatively affect the banking sector. For example,

Dam and Koetter (

2012) analysed that strong banking regulation can, not only improve bank managements by enforcing discipline on it but, also incentivise banks to increase the monitoring function. In the UK, the main reform of the Banking Reform Act (2013) was to ring-fence retail client deposits from any form of Investment Banking activity. The endeavour was conducted to make banks safer for the retail client and the taxpayer, however comes with additional costs to be incurred by banks (

Morse 2015). Alternatively,

Korotana (

2016) argues that a regulatory regime based on the concept of ‘whistle blowers’ and economic incentives (also found in Dodd–Frank Act) may be better suited than the style of ring fencing proposed in the Banking Reform Act (2013).

There are a number of works against banking regulation, for example

Gropp and Vesela (

2004) argued that these actions cause more harm than good to the banking sector. A fact that is often discussed in the literature is that banking regulation increases moral hazard due to the decline in market discipline and banks’ anticipation of bailouts. In addition,

Fahri and Tirole (

2012) showed that systematic regulation policies cause a collective moral hazard problem because they allow banks to access cheaper capital, so that they would increase their borrowings and reduce their liquidity. In this context larger banks, which might be supposed to be “too big to fail”, are more strongly incentivised than smaller banks to undertake risky strategy due to the government safety net.

Casu et al. (

2015) reported an analysis of causes of moral hazard such as deposit insurance, lender of last resort, and “too big to fail”; especially this last one is caused by the government safety net. Furthermore, many of the market failures can culminate in moral hazard problems because the risk taking party does not bear all of the associated costs of their activities but gains all of the associated benefits. Such moral hazard, as pointed out in

The Turner Review (

2009), can infect the entire financial markets forcing many of their participants to take an excessive amount of risk.

The topic of market failure, which can be caused by asymmetric information or negative externality, is very commonly discussed in the literature; indeed this can be considered one justification for banking regulation. As accentuated by

Casu et al. (

2015) banking regulation can take different forms from deposit insurance to capital requirement, bank licensing, and regular examinations of banks.

Goodhart et al. (

1998) analysed systematic regulation as regulation concerned mainly with the safety and soundness of the financial system, whereas prudential regulation deals mainly with consumer production, and finally, conduct of business focuses on how banks and financial institutions conduct their businesses. Regulators’ main concern is that the failure of one bank can have a contagious domino effect leading to the failure of other banks.

Bush (

2009) argued that one of the main reasons for the recurring debate is that many regulatory agencies supervising the banking sector have failed to prevent banking crises or bank collapses in several countries. Bank failure is in fact connected to banking crises, a review of the available literature on the last financial crisis revealed a number of potential market failures that could have caused different financial markets to deviate from their standard functions.

The Turner Review (

2009) examined some examples: (a) information deficiencies in both securitization markets and the market of home loans; (b) markets were not competitive; and (c) the presence of regulatory interventions such as the use of depositor protection schemes and bank bailouts.

Rajan (

2010) and

Wilmarth (

2011) argued that the main cause of the financial crises was the excessive risk-taking by financial institutions.

The Banking Reform Act 2013 is the main regulatory response to the financial crises in the U.K. and, this research will add value to this line of literature by providing evidence regarding the market’s evaluation of the effectiveness of the present Act.

Chortareas et al. (

2013) argued that banking regulation can take the form of precise rules, but is often inaccurate if such rules do not actually reflect risks faced by banks; this could lead to holding either excessive or not enough capital. More importantly, he explained that insufficient capital increases the risk of bank failure while unnecessary capital imposed excessive costs on the bank. He also suggested that to find a balance some extreme regulations needed to be introduced, for example, the Basel Committee II established a list of “best practices” for the regulation and supervision of banks in order to improve stability of the system, risk management practices, and market discipline via enhanced risk based capital and the disclosure requirement. Particular attention has been given to the capital adequacy requirement covered into Pillar 1 of Basel II which aimed to provide tools so that banks can hold less risky portfolios and manage the risk-taking behaviours of banks (

Zhang et al. 2008).

There is nowadays, a large amount of theoretical and empirical work on how the capital adequacy requirement has an effect on the stability of the banking system. Some studies such as

Blum (

1999) argue that an inadequate level of the capital adequacy requirement ends up by increasing the fragility of the banking system, whereas other studies found evidence that a higher capital adequacy requirement has a positive effect on the bank stability (

Zhang et al. 2008;

Chalermchatvichien et al. 2014). Additionally, an important study conducted in banking regulation by

Barth et al. (

2004) showed that the link between capital requirements and stability was not strong enough under Basel I.

Arnold (

2014) and

Casu et al. (

2015) argued the fact that Basel II capital rules allowed the largest banks to use their own internal models for assessing risk and capital adequacy positions, lead the big banks to hold less capital for regulatory purpose. This, inevitably, contributed to the 2007–2009 banking crisis. Indeed Basel II aimed to improve the assessment of the risk-weighted assets used to compute the capital adequacy ratio; however this has also been the central point of many criticisms as it should have paid more attention to provision of effective rules and guidance for the management risk (

Tchana 2012). More recently, a new regulatory framework has been introduced, Basel III, which require banks to hold more capital and higher quality capital than under Basel II, moreover this will oblige banks to respect three additional ratios: leverage ratio, liquidity coverage ratio, and net stable funding ratio, these three constraints along with the capital ratio, which existed before, have to be compliant simultaneously.

McNamara et al. (

2014) argued that Basel III strongly increases the complexity of bank management by introducing these new three ratios and by the requirement for more and higher loss absorbing capital.

Another strand of literature looks into the relationship between the measure of bank diversification, performance, and risk.

Elsas et al. (

2010) provided strong evidence that bank diversification did not reduce shareholder value but instead improved bank profitability and overall value. By contrast, the

Leaven and Leaven (

2007) study is very much relevant to this part of the literature, the criticism by these authors’ work is that diversification has a negative impact on bank performance, however there are instruments that could be put in place to overcome these impacts.

Elsas et al. (

2010) showed that the difference of these opposite views was due to the diverse measures for banks value and also because they did not use a profitability control in their major regression. Furthermore,

Stiroh (

2004) finds that diversification is associated with more volatile activities and lower risk-adjusted return. On the other hand,

Stiroh and Rumble (

2006),

Mercieca et al. (

2007),

Beale et al. (

2007), and

Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (

2010) examined that diversification of financial institutions is offset by greater exposure to more volatile activities and that bank performance could be improved by diversifying revenues. Finally, some recent studies, such as

Duchin and Sosyura (

2014), argued that the overall risk for banks is increasing specially for those institutions where regulations are strongly politically influenced as they are more likely to receive financial support.

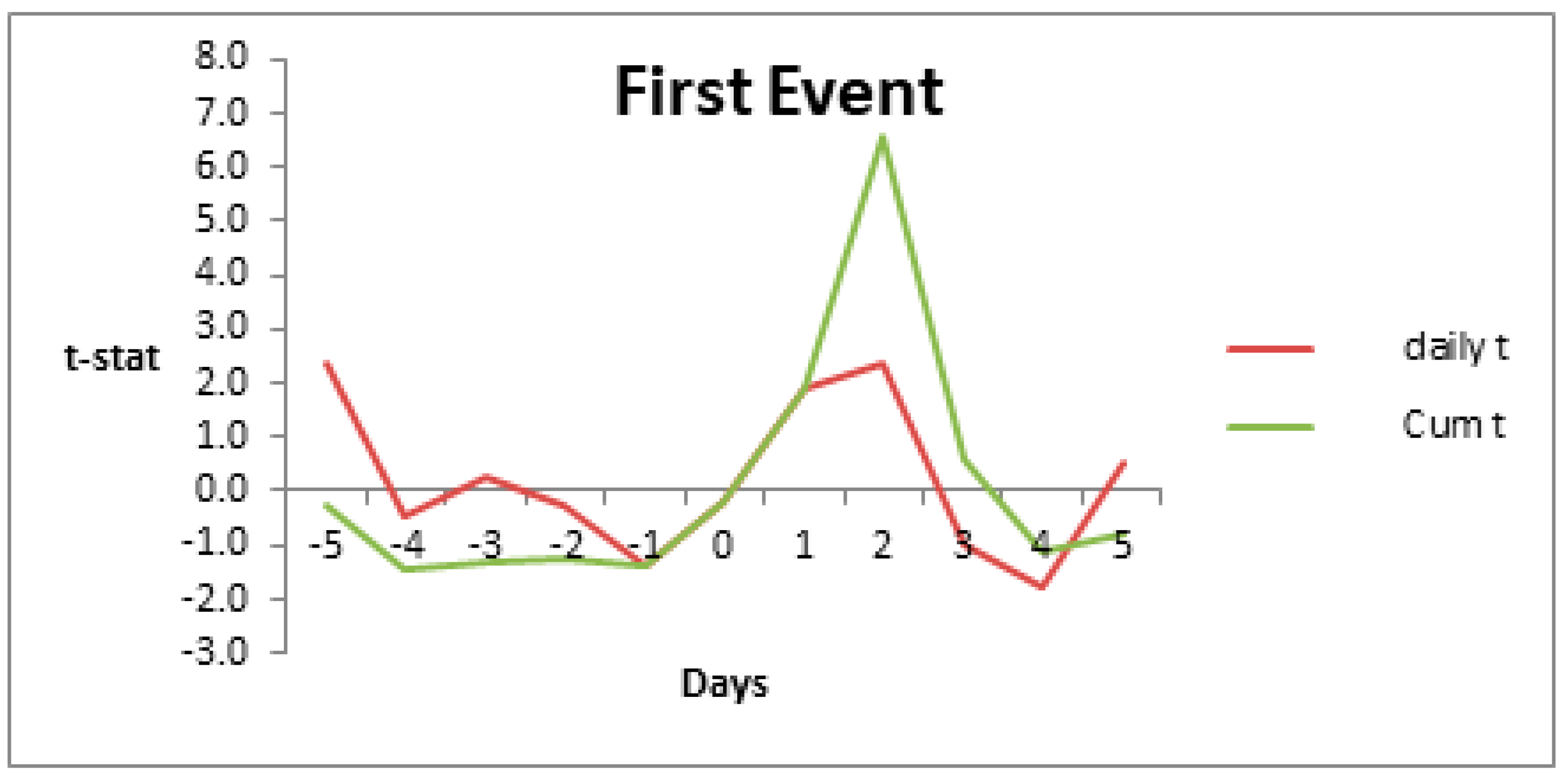

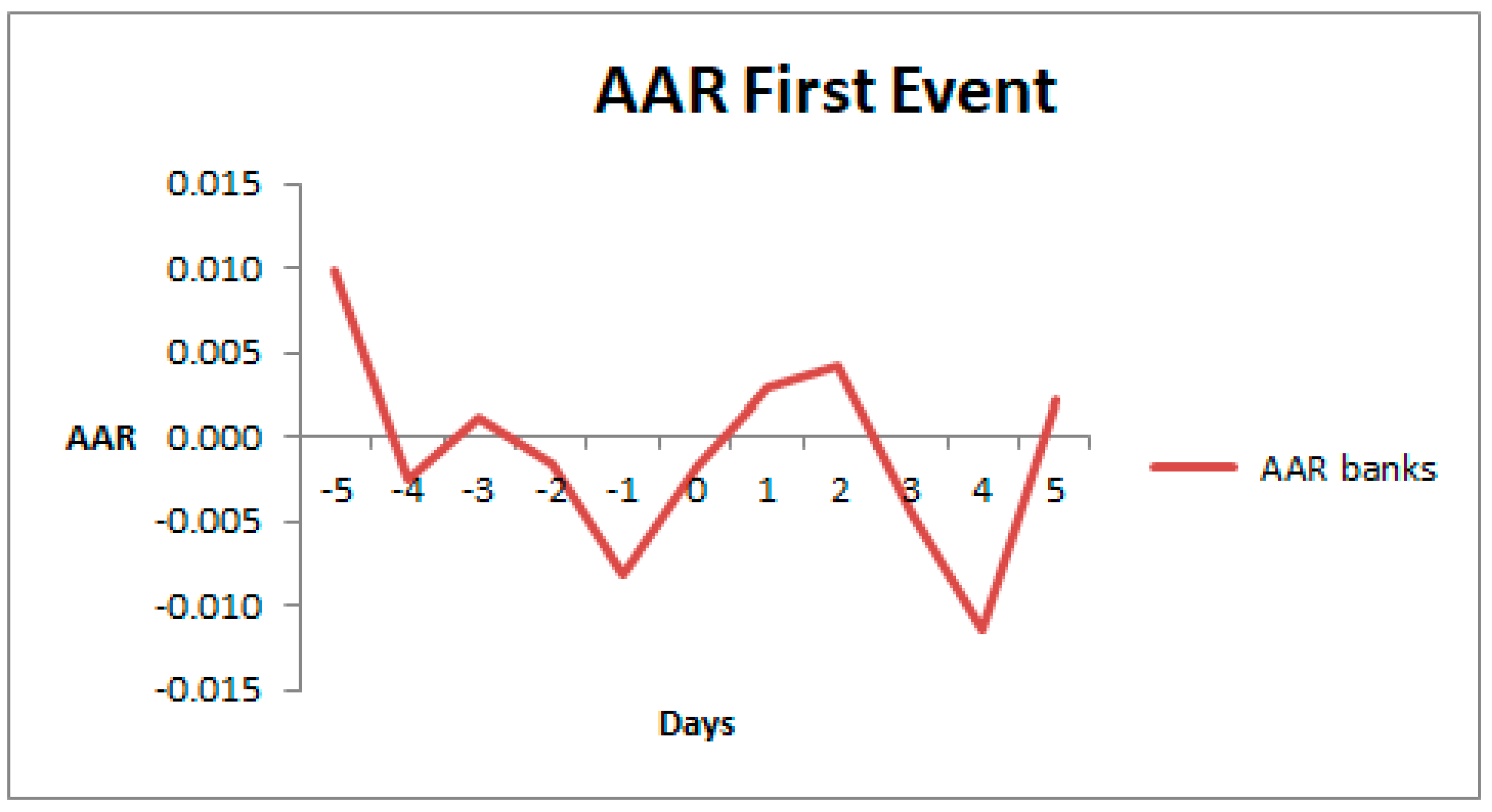

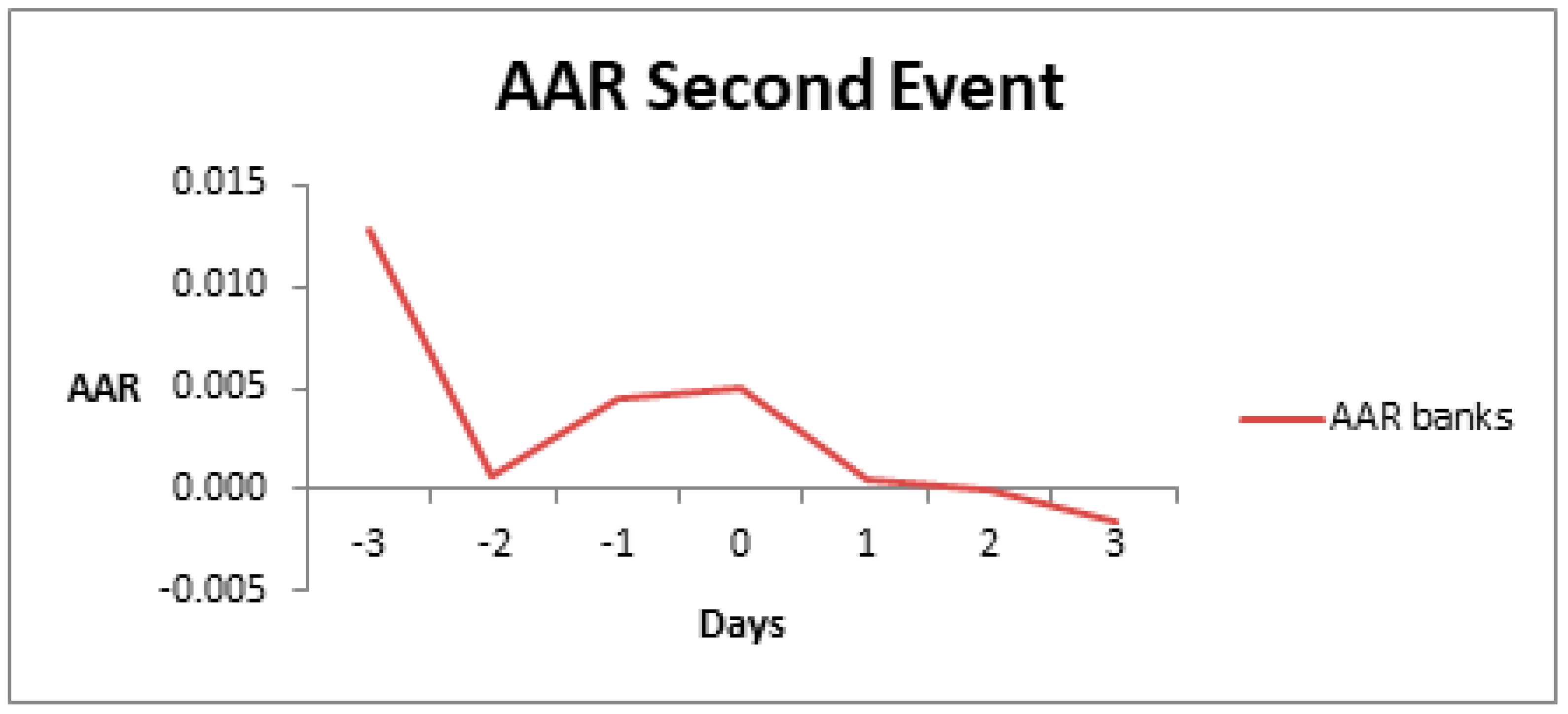

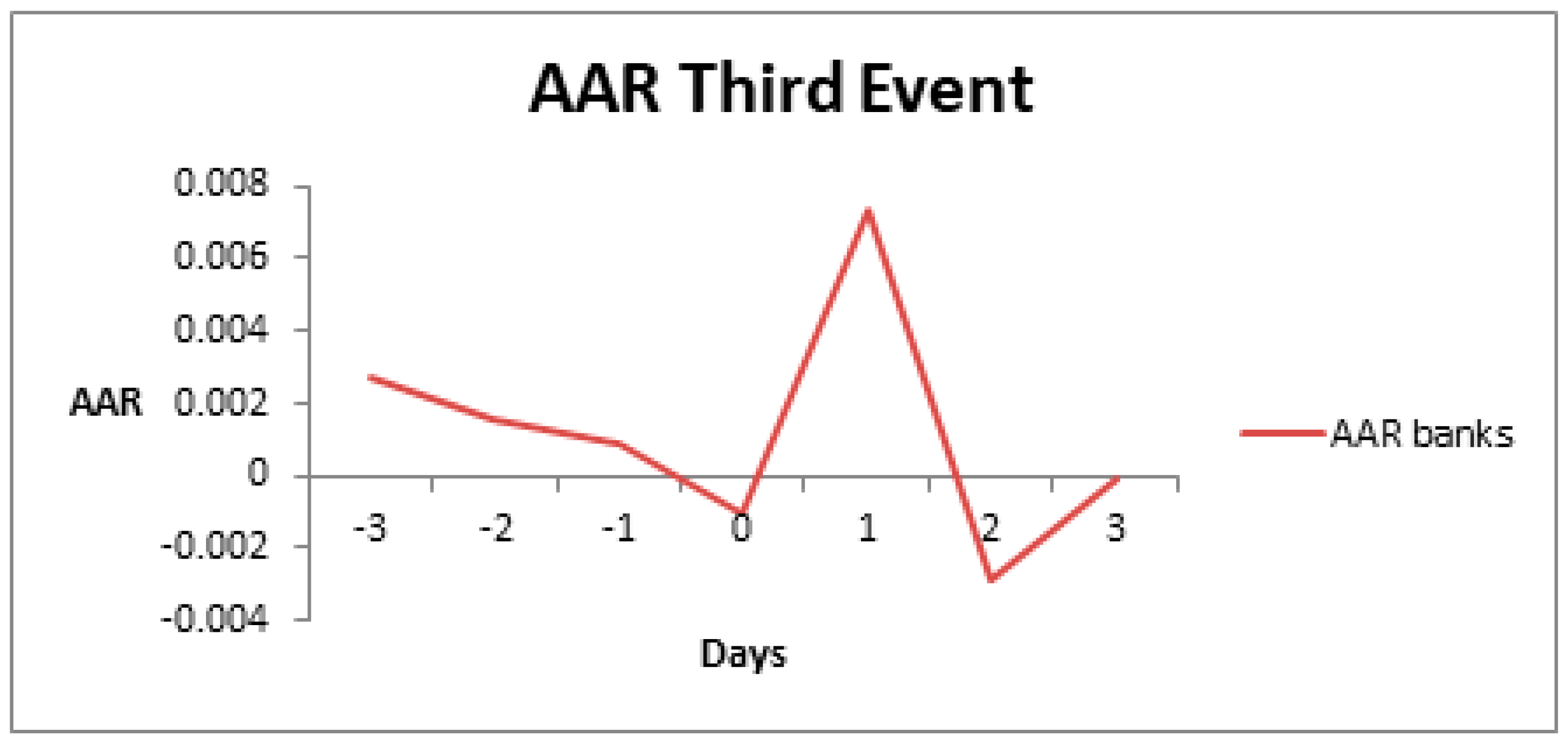

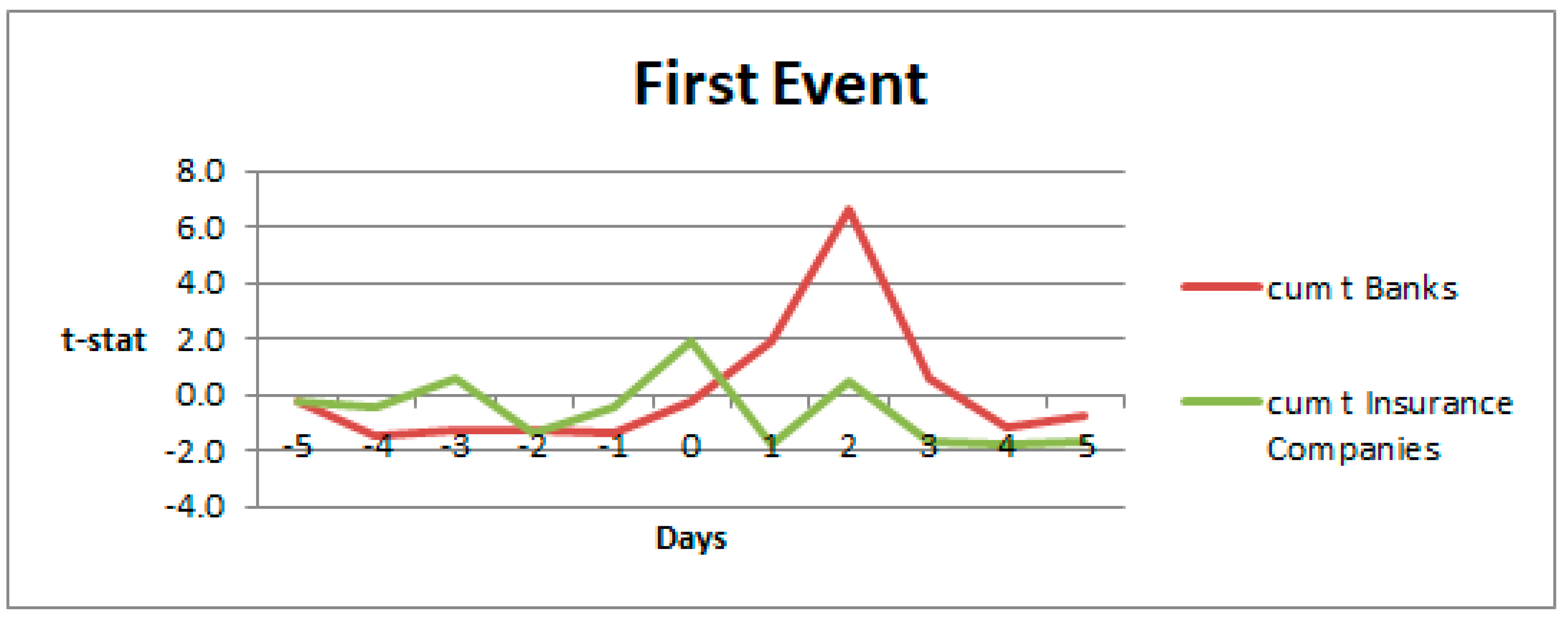

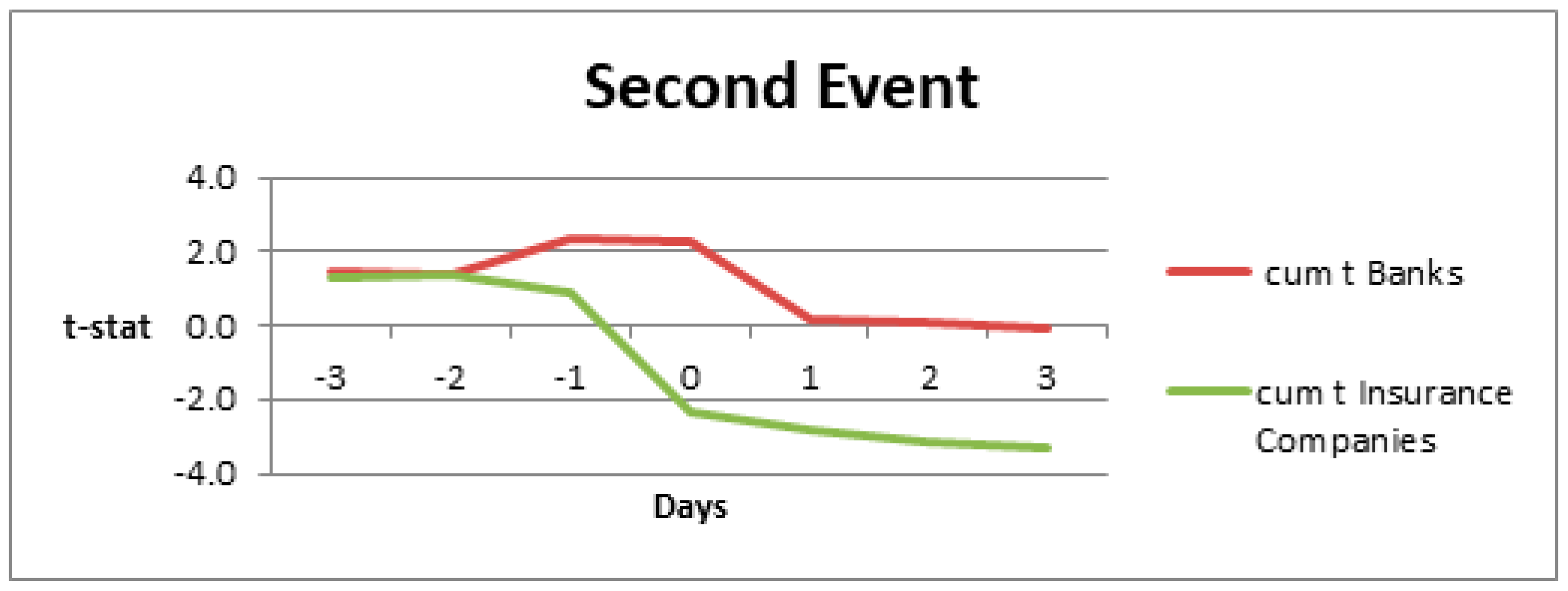

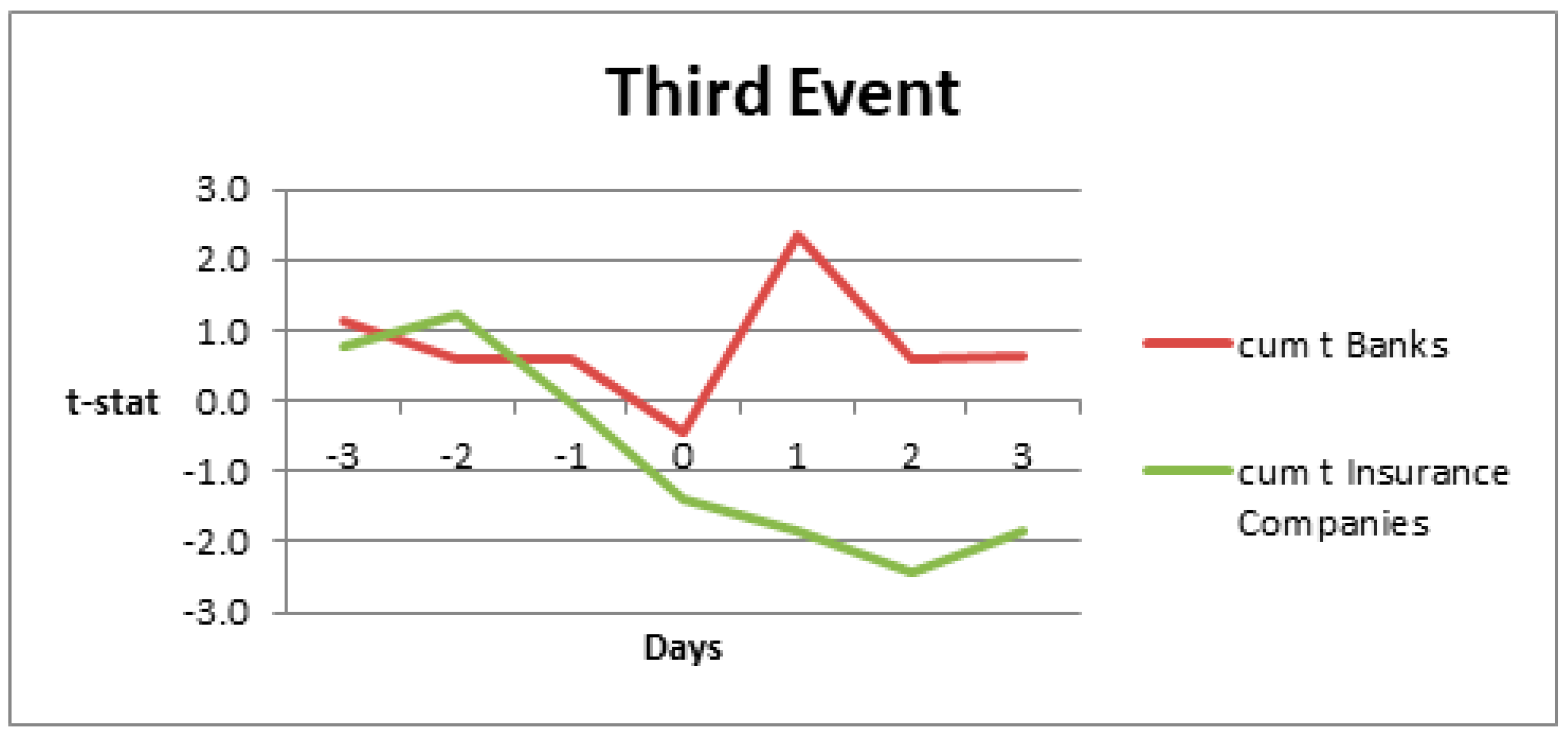

To end this section: past studies have looked at market reactions to deregulatory Acts and reforms. As pointed out by

Andriosopoulos et al. (

2015) the rationale in these studies is that the market is the best judge of the efficacy of financial reforms and their impact of the risk and return for financial institutions.

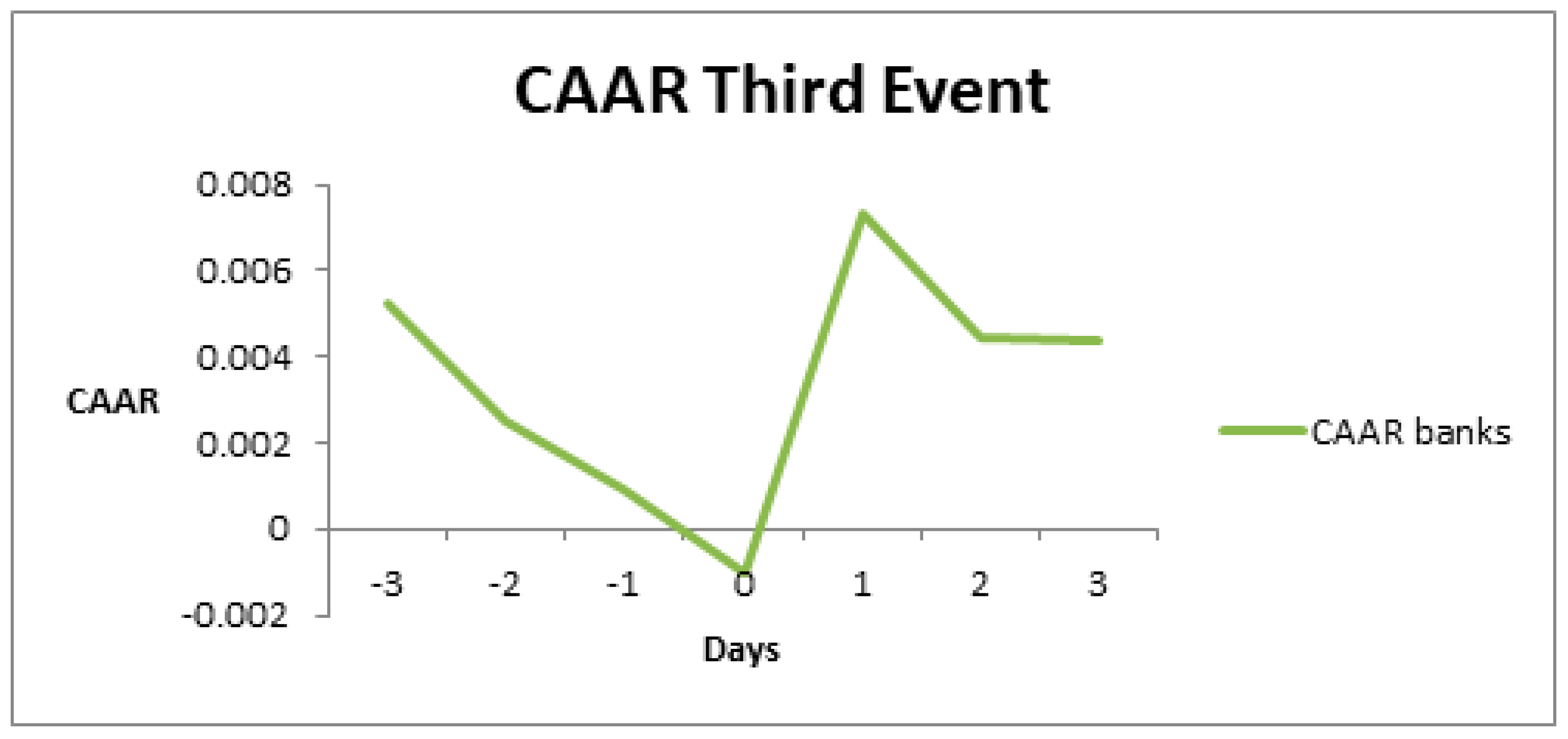

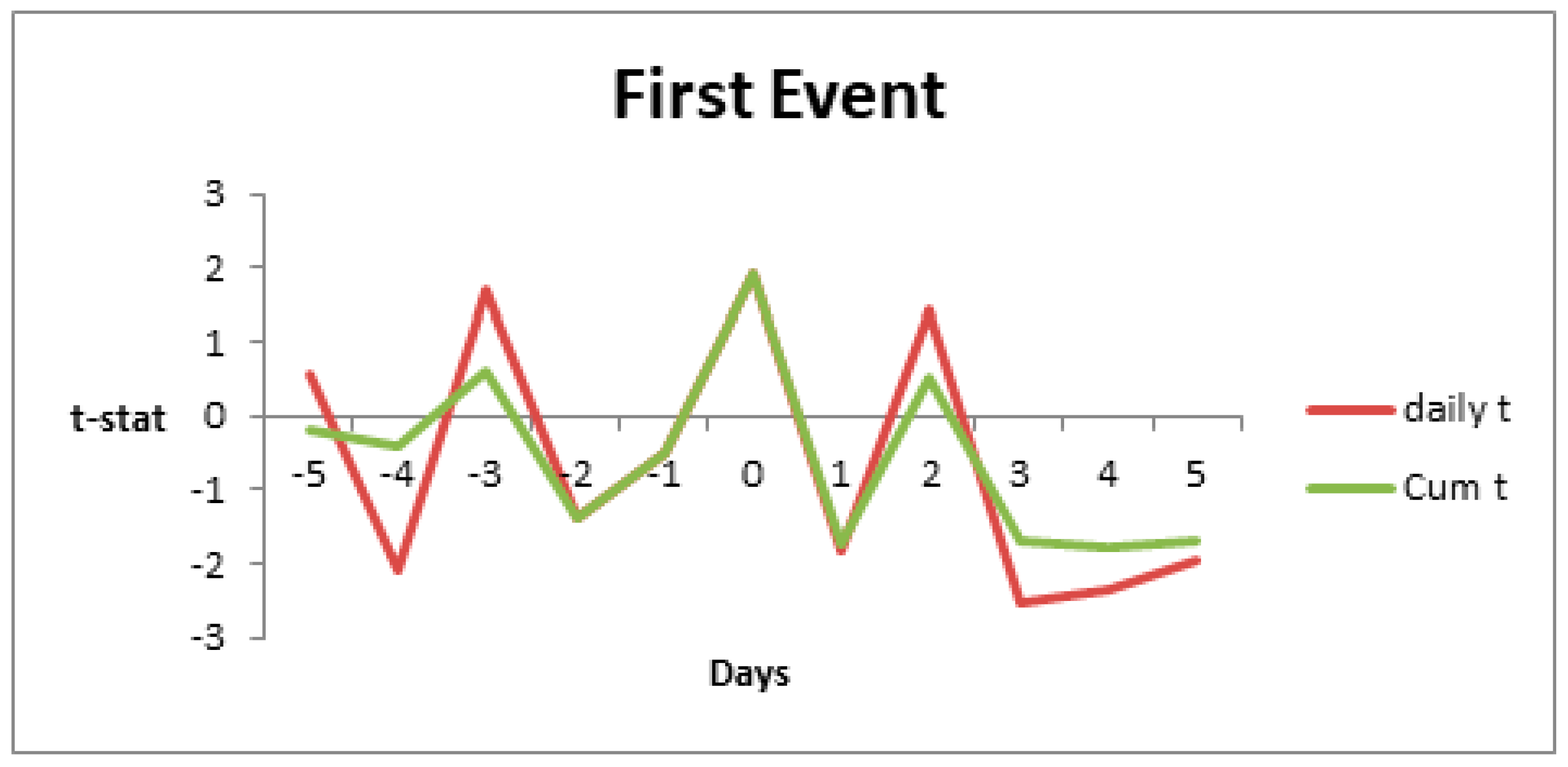

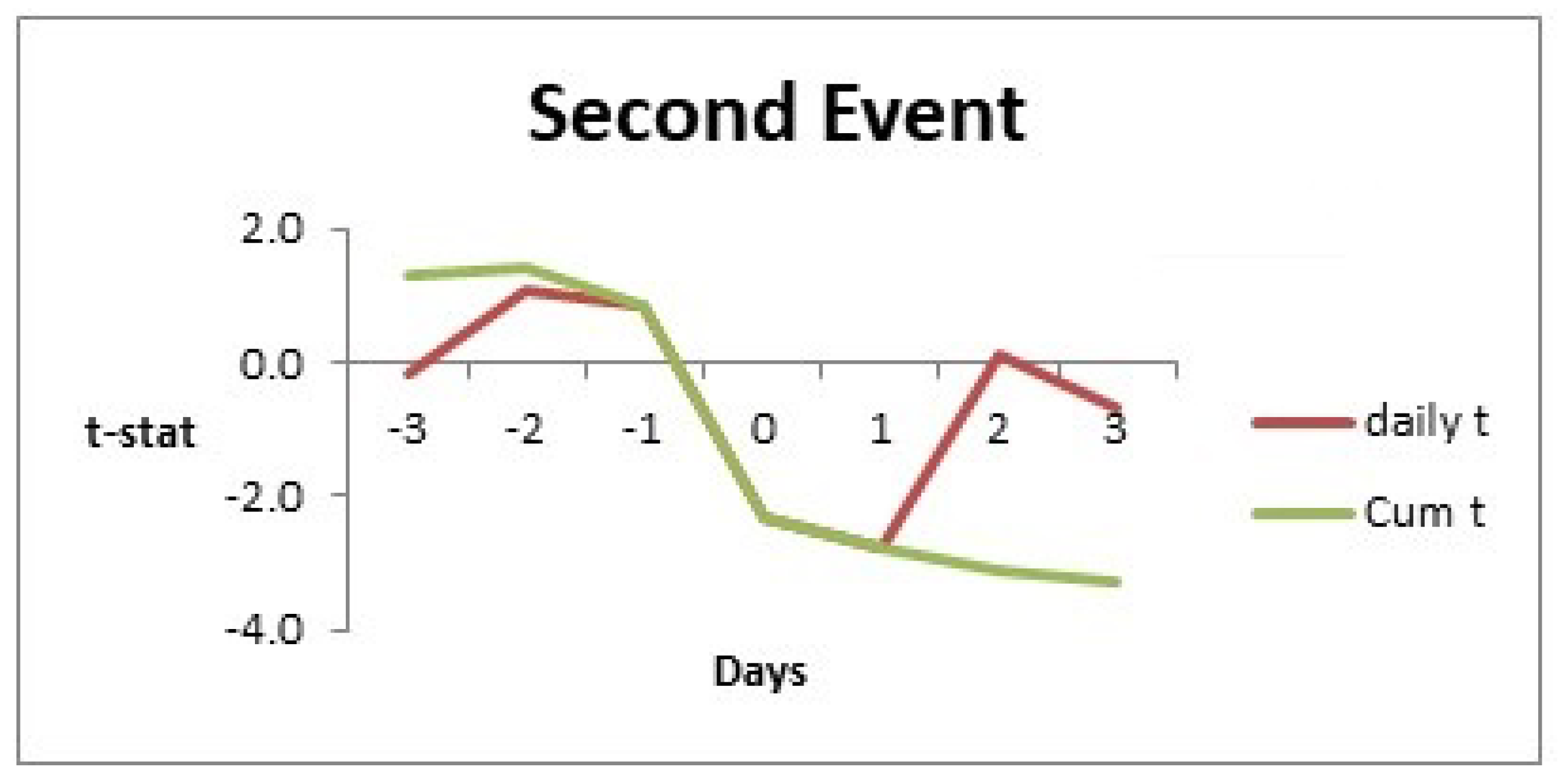

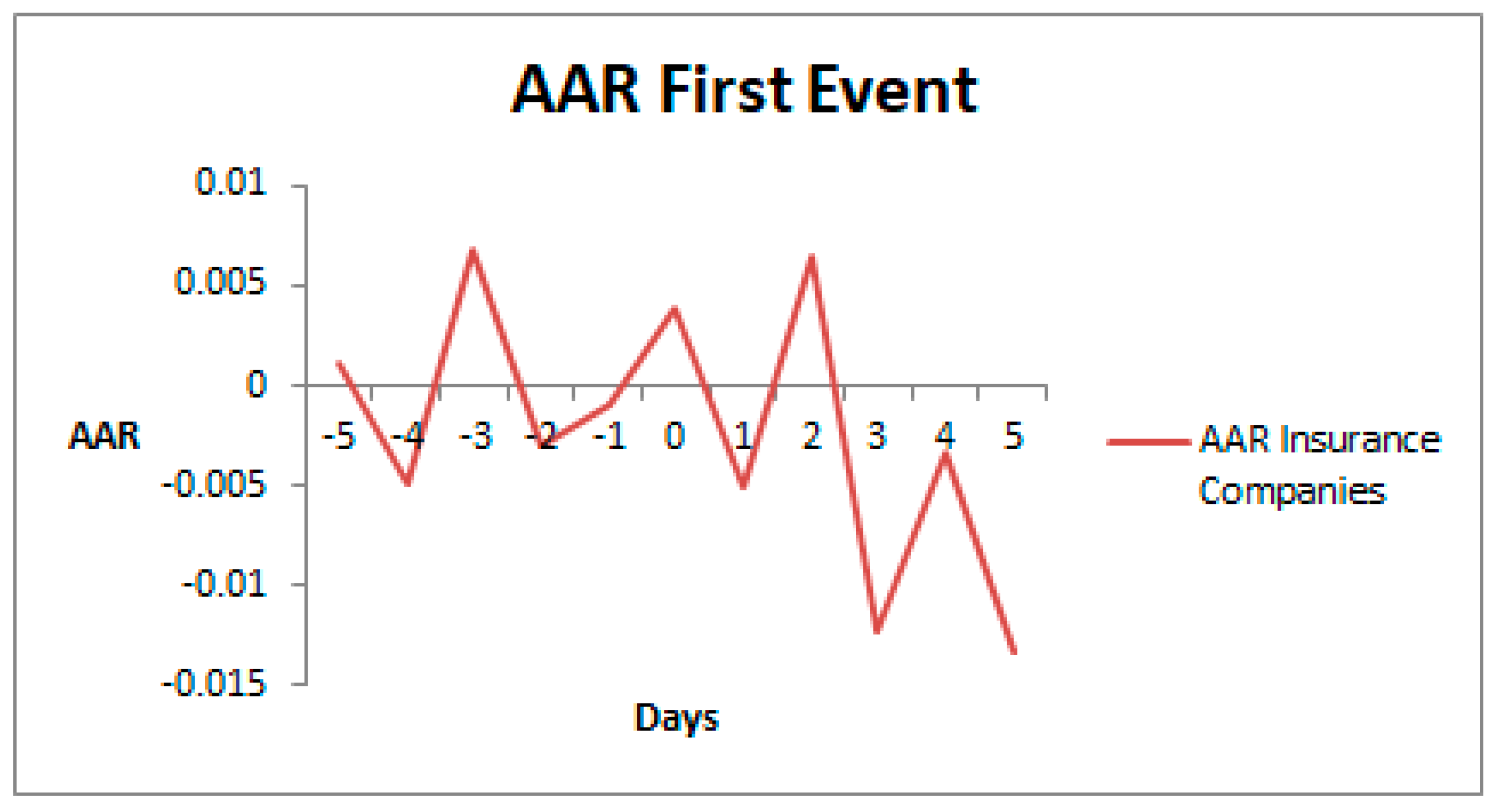

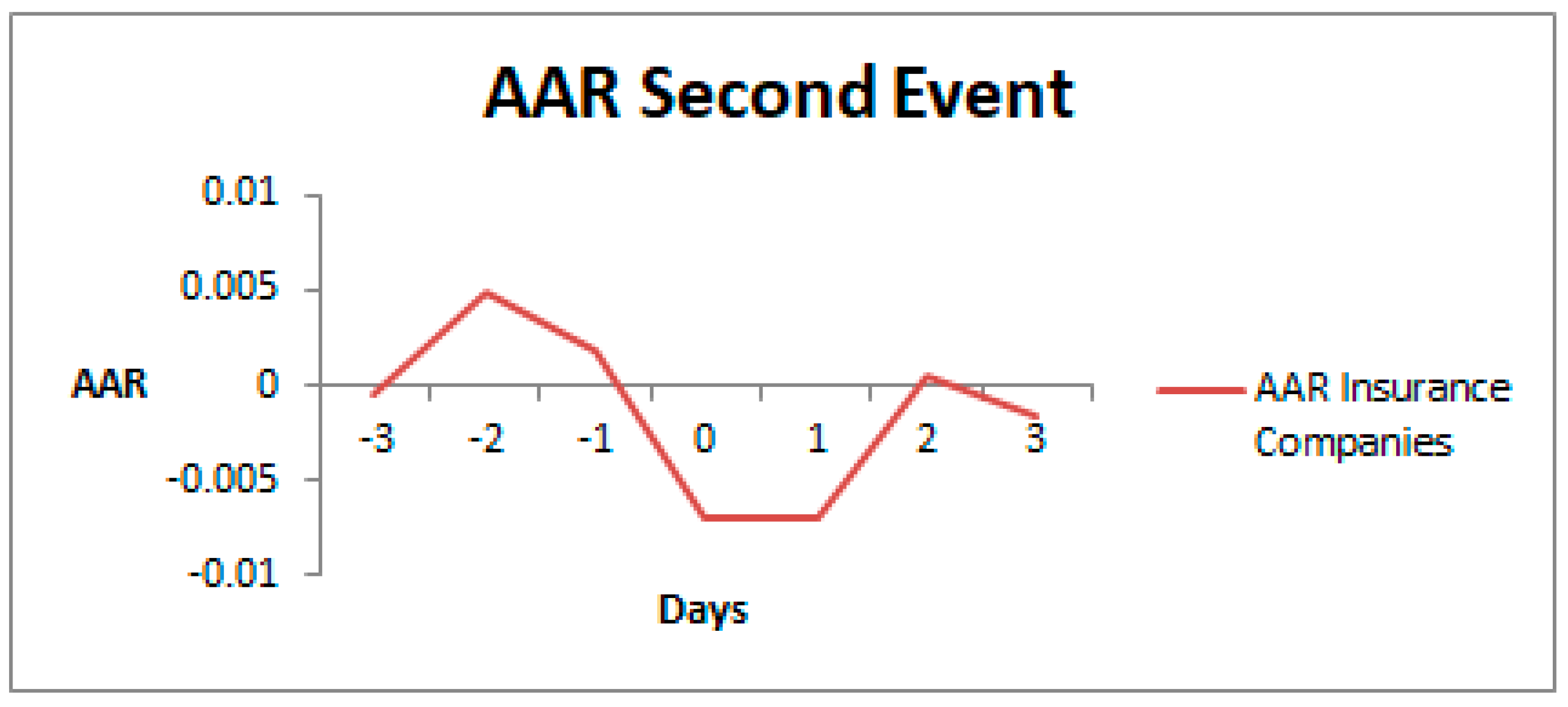

Schäfer et al. (

2013) analysed the reaction of the stock return of banks from four major regulatory reforms (Dodd–Frank Act in the U.S., the reforms proposed by the Vickers report in the U.K., the restructuring law and bank levy in Germany, and the too-big-to fail regulation in Switzerland) in the aftermath of the subprime crises employing an event study methodology and focusing on Europe and United States. They found that all reforms succeeded in reducing bailout expectations, especially for systemic banks, and that banks’ profitability was also affected as equity returns were resultantly lower.

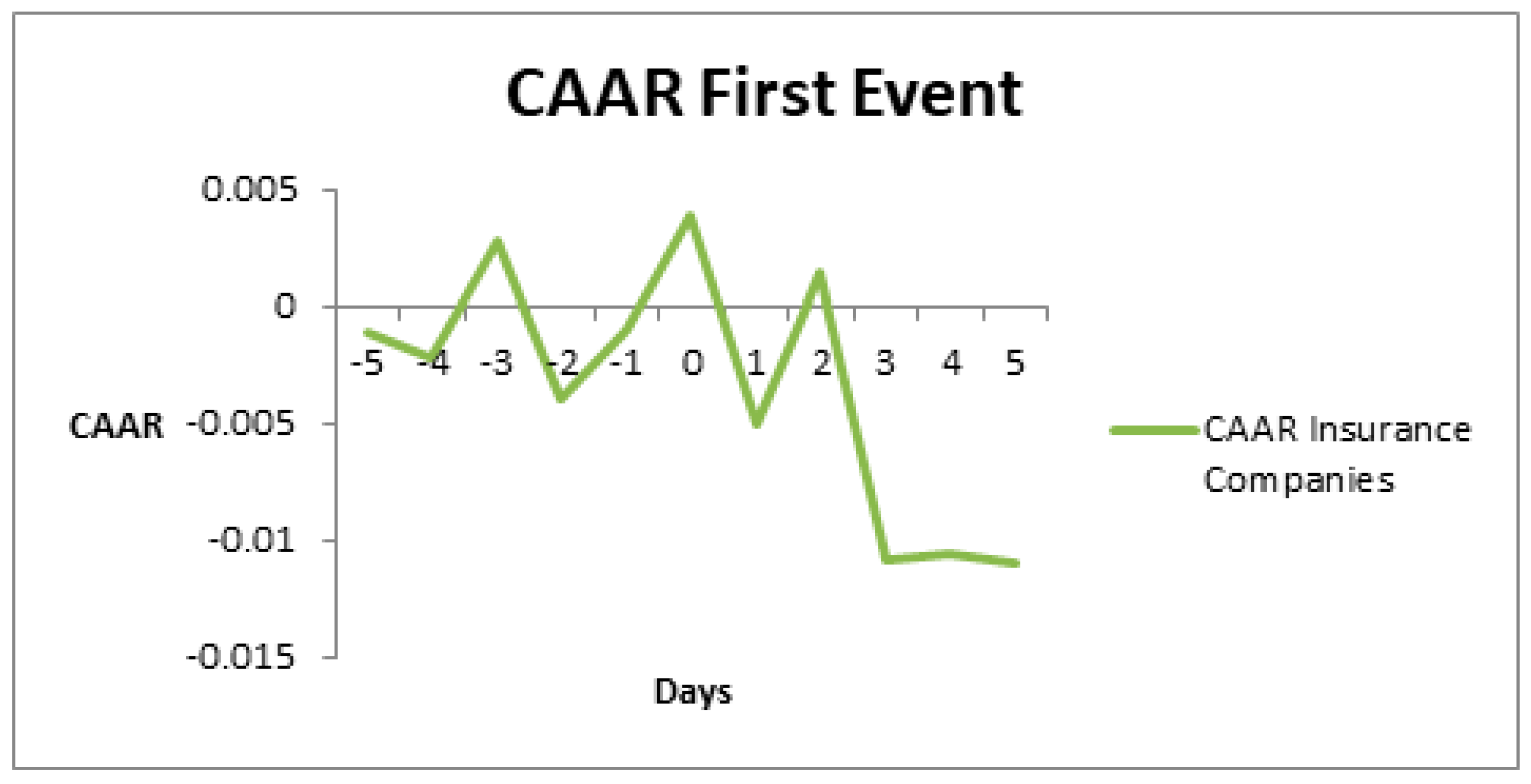

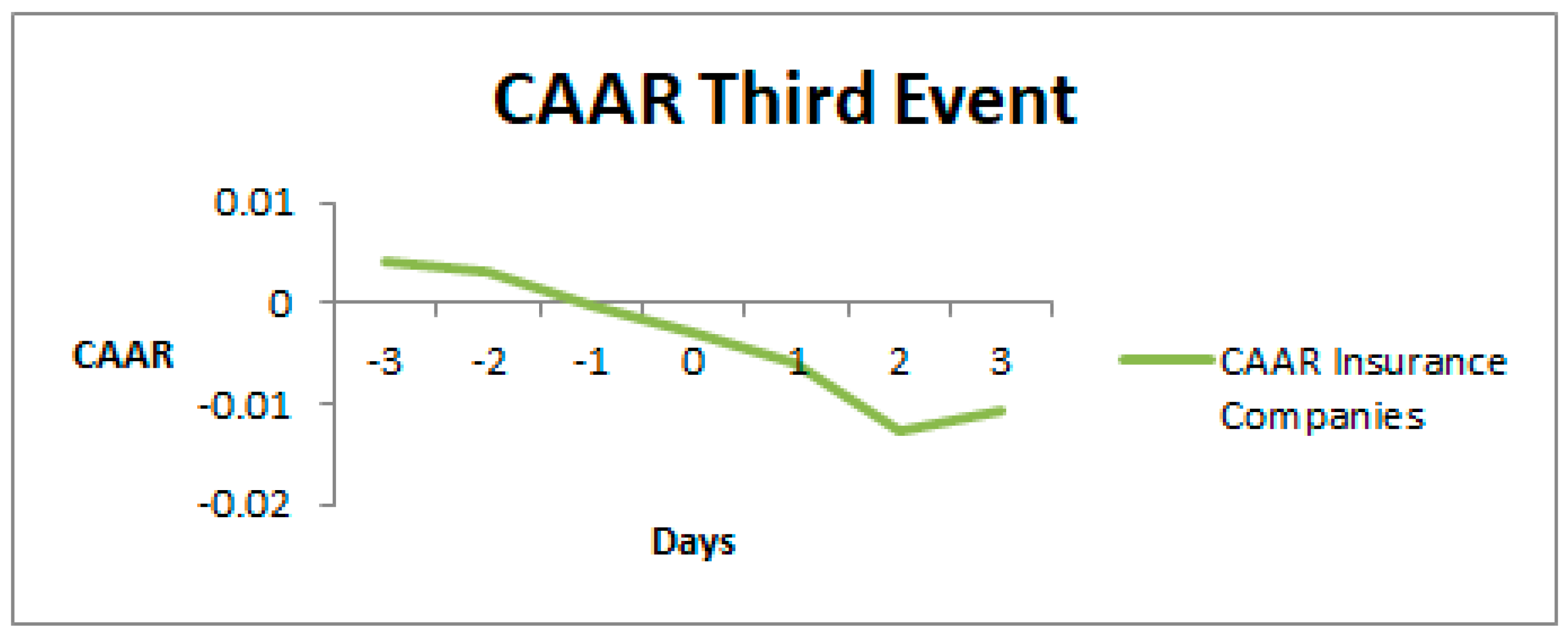

Carow and Heron (

2002) tested the reaction on the stock market to the passage of the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 (FSMA); they found negative returns for commercial banks and positive returns for investment bank and insurance companies around the announcement of the Act. In a similar study,

Hendershott et al. (

2002) found that insurance companies responded positively to deregulation and that these companies gained most of the benefits. Other studies, such as

Carow (

2001), reported that insurance companies, compared with other financial institutions, have important and positive stock price reaction after the impact of deregulation. Finally,

Johnston and Madura (

2000) analysed financial institutions, including commercial banks, insurance companies, and brokerage and found that they generally have a positive and important valuation effect upon merger announcements. There seems to be a lack of studies focusing specifically on this area in the United Kingdom, as the current literature is primarily focused on U.S. markets.

There are a large amount of studies in the literature examining the impact of changes in bank regulation on bank equity value, for example

Madura and Bertunek (

1995) found a positive response to the passage of the 1991 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act by small and medium-sized banks, but a negative effect on large banks.

Spiegel and Yamori (

2003) examined the impact of two important regulatory reforms in Japan on bank equity values.

While previous literature has documented different aspects of financial reforms in the banking sector, no research has been dedicated to the measurement of risk adjusted returns and abnormal returns specifically associated with important legislative dates of the Banking Reform Act 2013 in the U.K. This study will bridge this gap by examining the effects of legislative dates on stocks and how banks and insurance companies should adjust to appropriately manage portfolio risk.