1. Introduction

Customer segmentation is a critical task in marketing and financial services, as it allows financial institutions to tailor products, optimize campaigns, and allocate resources more effectively. In practice, banks and credit institutions often categorize customers based on behavioral patterns such as transaction frequency, repayment history, and engagement with financial products.

Among the widely adopted approaches, RFM (Recency, Frequency, Monetary) analysis has been widely applied as a segmentation tool in marketing and customer relationship management as it provides a straightforward, interpretable and effective behavioral profile of customers. By focusing on how recently a customer has transacted, how frequently they engage, and the monetary value of their activities, RFM has proven effective in predicting customer behavior. RFM analysis is particularly prevalent in retail and financial industries due to its simplicity and effectiveness (

Bhatnagar & Ghose, 2004;

Rajput & Singh, 2023) Several studies have demonstrated that RFM segmentation can serve as a reliable benchmark for evaluating more complex clustering methods, providing a reference point for alignment with business objectives (

Fader & Hardie, 2007;

Kumar & Reinartz, 2016;

John et al., 2023). However, while RFM is highly interpretable, it often relies on arbitrary thresholds, limiting its ability to capture nuanced behavioral patterns in large-scale datasets (

Malthouse et al., 2013).

Researchers have highlighted the limitations of the RFM model and suggested various extensions. Some studies have expanded RFM by adding new dimensions or integrating it with advanced clustering techniques. For example,

Wei et al. (

2012) applied RFM in combination with K-Means to improve customer targeting in e-commerce, while

Birant (

2011) proposed the RFM-Igain model, which incorporates information gain as an additional factor. In the tourism sector,

Y.-L. Chen et al. (

2009) enriched RFM with customer satisfaction metrics, and in telecommunications,

Bose and Chen (

2009) adapted the framework for churn prediction. These contributions demonstrate the flexibility of RFM across industries. More recently,

Marín Díaz (

2025) introduced a fuzzy-XAI framework integrating RFM, 2-tuple modeling, and strategic scoring for segmentation and risk detection, showing how explainable AI can make RFM-driven segmentation more transparent and actionable. The study (

Mosa et al., 2023) emphasized that RFM offers a solid foundation for segmentation in the banking sector, but its rigidity necessitates enhancement through automated techniques to better capture evolving customer behaviors.

To overcome these limitations, machine learning-based clustering algorithms such as KMeans and Hierarchical clustering have been widely adopted. Among clustering approaches, KMeans has been one of the most widely applied due to its computational efficiency simplicity, and intuitive centroid-based representation. KMeans is a partition-based, centroid-driven method that minimizes intra-cluster variance and is computationally efficient for large datasets (

MacQueen, 1967;

Jain, 2010). However, studies also highlight its limitations: sensitivity to initialization, the need to pre-define the number of clusters, and an implicit assumption that clusters are spherical and of similar size (

Likas et al., 2003). While KMeans is scalable and efficient for large datasets, its statistical validity does not always guarantee business interpretability—an issue especially relevant in credit risk applications where decision transparency is essential (

Tang, 2025).

Hierarchical clustering offers an alternative that emphasizes interpretability and does not require pre-specifying the number of clusters. Agglomerative hierarchical clustering, particularly with Ward’s linkage, has been shown to produce meaningful nested structures, making it easier to visualize relationships between customer groups (

Murtagh & Legendre, 2014;

Rokach & Maimon, 2005). While more computationally intensive than KMeans, Hierarchical clustering provides flexibility in exploring cluster solutions at multiple granularities, which is particularly useful in marketing and credit risk applications (

Gan et al., 2007;

John et al., 2023).

Overall, the literature indicates that combining rule-based RFM segmentation with clustering methods offers a powerful balance between interpretability and scalability in customer segmentation. However, purely algorithmic clusters can be difficult to interpret and align with business insights. To address this, we apply the Hungarian algorithm (

Kuhn, 1955;

Munkres, 1957) to align machine-generated clusters with well-established RFM segments. This alignment facilitates comparison with business-recognized categories.

As part of exploring alignment methods, several works have focused on using the Hungarian algorithm (also called the Kuhn–Munkres algorithm) for matching clusters or partitions to predefined or ground-truth categories. The algorithm solves a cost-minimization assignment problem in polynomial time, making it suitable for aligning machine-learned clusters with external labels.

For example,

Goldberger and Tassa (

2008) proposed a Hierarchical clustering algorithm that uses the Hungarian method as a building block: they view pairwise distances between data points, use Hungarian to generate disjoint cycles (min-weight cycle covers), then hierarchically merge them. Their algorithm can handle non-convex clusters and automatically determine the number of clusters.

Another relevant study is

Kume and Walker (

2021), where the authors introduce a way to score clusters (“utility”) and, when needed, use the Hungarian algorithm over permutations of cluster-centroid vs. label centroids, in order to align cluster results in a way that better reflects the external or domain labels.

These studies show that the Hungarian algorithm is useful not only in theoretical algorithm design but also in practical clustering tasks: aligning clusters, resolving label permutations, automating the match between data-driven partitions and human-interpreted categories. Its importance for interpretability in segmentation workflows is well supported in the literature.

While prior research has applied clustering algorithms and the Hungarian method in various analytical contexts, we found no studies that explicitly combine these elements to align machine-learned customer clusters with interpretable RFM-based behavioral segments in the context of dormant-portfolio management within financial services. The contribution here is therefore not the introduction of new algorithms, but the integration of existing methods into a reproducible and interpretable workflow tailored to RFM-based customer management.

This study proposes an automated system for customer segmentation that integrates rule-based RFM analysis with machine learning clustering algorithms, including KMeans and Hierarchical clustering. By exploring multiple cluster numbers, the system automatically identifies the optimal segmentation for each algorithm and aligns machine-learned clusters with RFM-defined labels using the Hungarian algorithm.

The contributions of the study are threefold:

A structured workflow that integrates rule-based RFM segmentation with machine-learning clustering and alignment.

A multi-metric evaluation framework combining internal validity measures (Silhouette, DBI) and interpretability-alignment metrics (ARI, NMI, homogeneity, completeness, V-measure).

A comparative assessment of the segmentation quality and interpretability of KMeans and Hierarchical clustering, providing operational guidance for reactivation and dormant-portfolio monitoring.

By integrating domain knowledge with automated clustering, this approach addresses the limitations of traditional segmentation, supports scalable analysis, and enhances the accuracy and interpretability of customer insights. Automation of the segmentation process ensures consistency across large datasets, allows rapid updates in response to changes in customer behavior, and reduces the potential for human bias. Importantly, the goal of this study is not to treat RFM as a ground-truth benchmark, nor to reward clustering algorithms for reproducing existing heuristic structures. Instead, RFM provides a familiar interpretability anchor against which machine-learned patterns can be examined. The alignment process allows analysts to identify where data-driven cluster structures reinforce long-standing business assumptions and where they diverge from them. In this sense, the contribution of the framework is not algorithmic novelty but the integration of automated clustering, interpretability alignment, and multi-metric evaluation into a reproducible segmentation workflow designed for practical use in financial-services environments. By selecting the RFM segmentation that matches the optimal number of machine-learned clusters, organizations can maintain interpretability while systematically exploring different segmentation granularities and improving targeting strategies in both marketing and credit-related contexts.

An important property of the proposed framework is that it remains fully adaptable across different institutions and datasets. The system does not rely on company-specific thresholds, predefined segment definitions, or manually determined numbers of clusters. Instead, it evaluates multiple candidate cluster granularities, assesses internal validity and alignment with interpretable baselines, and selects the configuration that best reflects the structure of the data at hand. This independence from fixed business rules or historical segmentation schemes makes the framework suitable for deployment across companies with diverse customer behaviors, product portfolios, and operational contexts. By allowing the data—not the organization’s prior assumptions—to guide the choice of segmentation, the system can generate tailored, company-specific cluster structures while maintaining interpretability and reproducibility.

Although this study is framed within the broader context of credit risk management, the available data pertain specifically to inactive customers—individuals who currently have no active contract but have historical repayment interactions with the institution. This group is more relevant for customer re-engagement, dormant portfolio monitoring, and behavioral profiling than for traditional credit scoring of active borrowers. The segmentation developed in this study therefore aims to support reactivation strategies, early behavioral risk detection within dormant portfolios, and portfolio-level monitoring, rather than core credit risk assessment. While Recency, Frequency, and Monetary variables are not credit-bureau-derived metrics, they capture behavioral repayment patterns that remain meaningful for risk-sensitive customer management activities such as collections prioritization, reactivation, and churn-risk assessment.

2. Methodology

This study investigates the effectiveness of clustering algorithms for customer segmentation by comparing rule-based RFM segmentation with machine learning–driven approaches. The methodology consists of five sequential components: dataset preparation, construction of rule-based RFM segments, application of KMeans and Hierarchical clustering across multiple candidate values of k, alignment of machine-learned clusters with interpretable RFM-based categories using the Hungarian algorithm, and evaluation using a combination of internal and external cluster validity metrics. The process is fully automated, allowing the system to test alternative segmentation granularities, compute performance metrics, and identify the configuration that best reflects the underlying behavioral structure of the dataset while preserving interpretability.

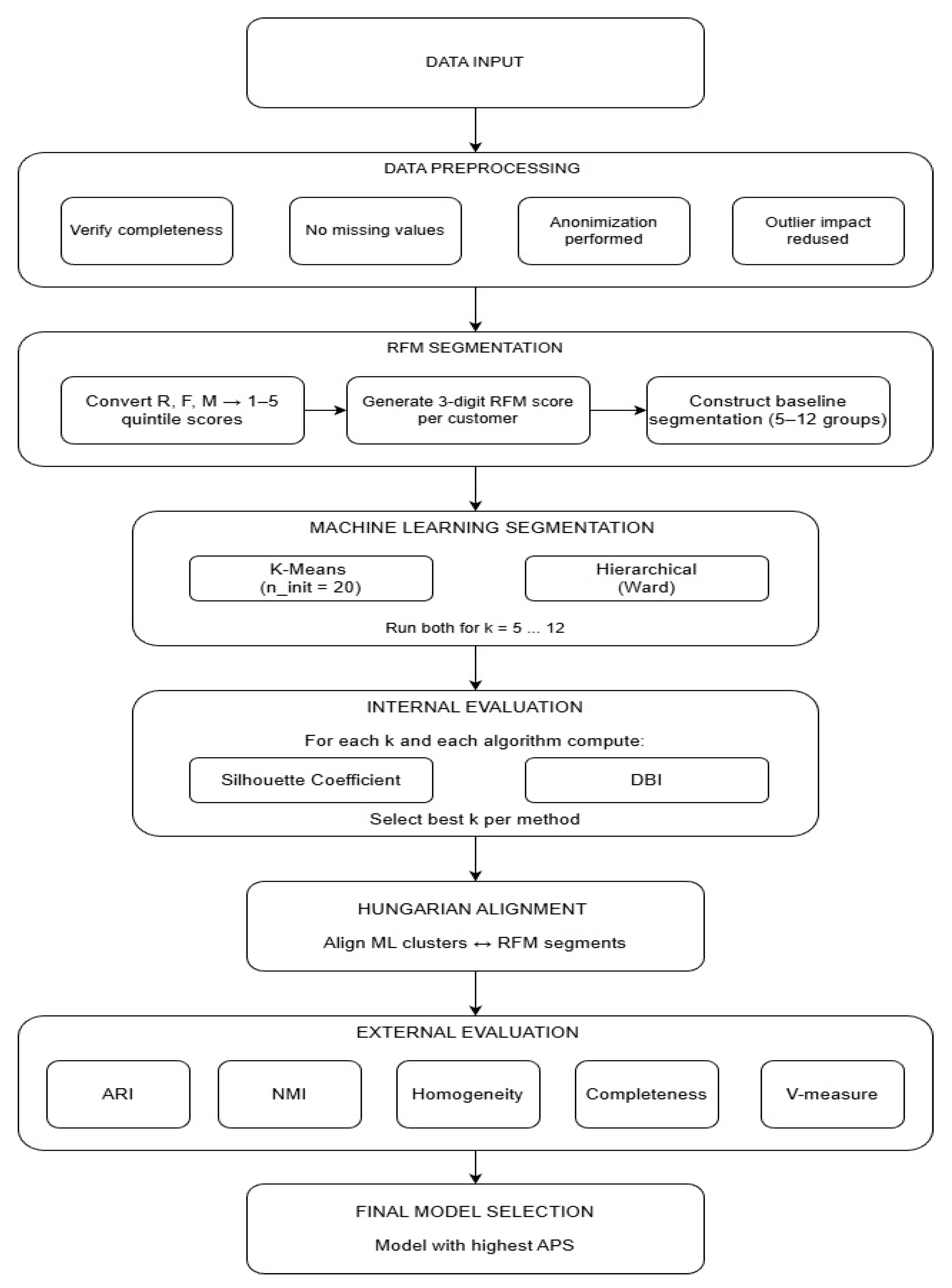

The full analytical pipeline is summarized visually in

Figure 1, which outlines each stage of the automated workflow—from data ingestion through RFM scoring, clustering evaluation, Hungarian alignment, and final model selection. Each of these stages is described in detail in the subsequent sections to provide methodological transparency and facilitate reproducibility.

2.1. Data Preparation

The primary objective of this segmentation is to focus on inactive customers, who form the main target group for the segmentation. Inactive customers are defined as individuals who do not currently hold an active contract at the time of the data snapshot but have previously engaged with the company by maintaining at least one contract. Identifying and analyzing this group is critical for understanding churn patterns, assessing retention risks, and designing targeted marketing or re-engagement strategies. By concentrating on these customers, the study aims to provide actionable insights that can guide marketing initiatives and optimize the allocation of resources in retention campaigns.

The dataset used in this study is extracted from institutional financial and operational systems, with all sensitive personal details anonymized before delivery. It covers a two-year period (1 July 2022–1 July 2024) and is approximately 26,500 customer-level aggregated records with one row per client. In accordance with the focus on inactive customers, the dataset includes only three RFM-like behavioral variables:

Recency value (R): number of periods since the customer’s most recent interaction with the company;

Frequency value (F): the number of interactions made within a fixed observation window;

Monetary value (M): the total spending or revenue generated by a customer in the same observation window.

In this study, the values used for the relevant dimensions are:

Recency: number of days since the customer’s last payment under contract;

Frequency: total number of contracts associated with the customer;

Monetary: realized return on investment (ROI) generated by the customer.

No additional features—such as other credit bureau data, demographic variables, or categorical attributes—are included. All preprocessing is carried out on these three numeric variables only.

No missing values are present in the dataset, because every inactive customer record contains complete behavioral information. Outliers are naturally mitigated through the use of quintile-based discretization, a standard RFM approach in which each variable is transformed into a score from 1 (lowest quintile) to 5 (highest quintile). This method not only reduces the influence of extreme values but also preserves comparability across customers. Because no categorical features are used, no additional encoding or transformations are required.

RFM-like variables are selected because, for inactive customers, traditional credit-risk indicators are no longer updated and therefore do not reflect current behavioral risk. In contrast, behavioral repayment history—captured through recency, historical contract frequency, and realized ROI—provides the most relevant and actionable information for dormant-portfolio assessment and re-engagement decision-making.

2.2. RFM Segmentation

RFM analysis is applied in this study as a benchmark segmentation method against which clustering approaches are evaluated. In this framework, each customer’s behavioral profile is quantified along three dimensions: recency, frequency and monetary value. To ensure comparability across customers, each of the tree dimensions is discretized into quintiles, resulting in a standardized scoring system ranging from 1 (lowest 20%) to 5 (highest 20%). The combination of these scores yields a three-digit RFM code (e.g., 545), which serves as the foundation for rule-based segmentation, consistent with established approaches in customer relationship management (

M. Chen et al., 2014).

Customers are then assigned to predefined behavioral groups by mapping RFM scores into interpretable categories that capture distinct engagement and value patterns. For example, customers with high values across all three dimensions (e.g., R = 5, F = 5, M = 5) are labeled “Champions”, reflecting their high activity and profitability. In contrast, customers with consistently low recency and frequency scores are classified as “Lost”, indicating long periods of inactivity and low business value. Between these extremes, intermediate categories such as “Potential Loyalists”, “Promising”, or “At Risk” provide a nuanced view of customer dynamics.

To provide a solid baseline for comparison with machine learning methods, RFM segmentation is performed at multiple levels of granularity, ranging from five to twelve segments. This approach aligns with common practices in the literature and highlights the flexibility of RFM analysis in adapting to varying business objectives (

M. Chen et al., 2014;

Kadiyala & Srivastava, 2011). A major advantage of this rule-based method is its transparency: marketing and credit teams can readily understand why a customer is assigned to a particular segment and use that insight to tailor interventions. However, while RFM is widely valued for its simplicity and practical relevance (

Rizkyanto & Gaol, 2023;

Hu & Yeh, 2014;

McCarty & Hastak, 2007), its fixed scoring boundaries can limit adaptability in complex datasets. These limitations motivate the integration of clustering-based methods, which are explored in the subsequent sections to enhance segmentation granularity and data-driven insights.

2.3. Clustering Approaches

To evaluate the potential of machine learning to provide more data-driven insights, two clustering approaches are applied directly to the RFM score features. Both are tested across multiple numbers of clusters (k = 5–12) to identify the most appropriate level of granularity.

2.3.1. K-Means Clustering

K-Means is a partition-based clustering algorithm (

Murphy, 2012) that aims to minimize within-cluster variance, also known as the sum of squared errors (

), by iteratively updating cluster centroids:

where

is the number of clusters;

is the set of points assigned to cluster

is the centroid of cluster

is an individual observation.

The algorithm proceeds iteratively in two main steps:

Each data point

is assigned to the cluster with the nearest centroid, using Euclidean distance as the standard metric:

where

is the cluster label assigned to observation

.

- 2.

Update step:

Centroids are recalculated as the mean of all points assigned to the cluster:

These steps are repeated until convergence, typically defined as no further changes in cluster assignments or when the reduction in falls below a predefined threshold.

In this study, the algorithm was run with multiple random initializations to reduce sensitivity to starting conditions.

2.3.2. Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering is an unsupervised learning technique that identifies nested groups in unlabeled data. Unlike partition-based algorithms such as K-Means, which optimize cluster membership around centroids, Hierarchical clustering builds a dendrogram—a tree-like structure that illustrates how clusters merge or split at different levels of granularity.

In this study, we applied agglomerative Hierarchical clustering with Ward’s linkage (

Ward, 1963). At each step, two clusters

and

are merged to minimize the increase in within-cluster variance (or error sum of squares, ESS). Formally, the criterion is:

where

are the number of points in clusters

and are the centroids of these clusters;

is the squared Euclidean distance between the centroids.

This criterion ensures that the pair of clusters chosen for merging leads to the smallest possible increase in total within-cluster variance.

The process starts with each observation as a singleton cluster and proceeds iteratively until all points are merged into a single cluster. The full set of merges is visualized as a dendrogram, and the branch can be “cut” at a desired level to obtain a clustering solution.

In this study, we truncate the dendrogram at multiple levels, k ∈ {5,6,…,12} to ensure comparability with K-Means and RFM segmentation.

2.4. Cluster Alignment

One of the challenges of unsupervised clustering is that the cluster labels generated by the algorithms do not correspond to the semantic categories used in business practice. For example, cluster “2” from K-Means may contain customers similar to the “Loyal” RFM segment, but there is no inherent mapping between them.

To resolve this, we apply the Hungarian algorithm (

Kuhn, 1955). The Hungarian method solves the classical assignment problem, where the goal is to find an optimal one-to-one mapping between two sets, in our case machine-generated clusters and predefined RFM categories, that minimizes the overall cost.

Let there be

machine-generated clusters and

RFM clusters. We define a cost matrix

, where each element

represents the distance between the centroid of machine cluster

and the centroid of RFM segment

. In this study, distances were computed in the three-dimensional RFM feature space using the Euclidean metric:

where

The assignment problem can be expressed as:

subject to:

Here, = [] is a binary decision matrix where if cluster is assigned to segment , and 0 otherwise.

The Hungarian algorithm guarantees an optimal solution in polynomial time O(), making it computationally efficient even for larger segmentation problems. Once the optimal mapping is obtained, the machine-generated cluster labels are relabeled to match the corresponding RFM categories, enabling direct comparison of segmentation quality.

This step ensures that the output of unsupervised learning can be meaningfully compared to the rule-based RFM system, allowing both interpretability and fairness in evaluation. By aligning algorithmic clusters with RFM segments, we combine the strengths of both approaches: the interpretability of RFM and the data-driven adaptiveness of clustering methods.

2.5. Computational Environment and Implementation Details

The automated segmentation workflow is implemented in Python 3.11 using the following versions of libraries: scikit-learn version 1.5.2, scipy version 1.13.1, numpy version 2.0.2, pandas version 2.0.303 and matplotlib version 3.9.4. All experiments are run on a system with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB RAM under Windows 10. Execution-time comparisons exclude preprocessing steps, focusing solely on clustering performance.

3. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the quality of the clustering results, both external and internal validation measures are applied. This dual approach was chosen because clustering needs to be assessed from two perspectives:

External metrics assess how well the machine-generated clusters align with a meaningful business benchmark—in our case, the rule-based RFM segments. This ensures that algorithmic clusters remain interpretable and relevant for decision-making.

Internal metrics assess the statistical quality of the clusters themselves—regardless of external labels—by examining how compact and well-separated the groups are. This ensures that the structure is robust, even if business labels are not considered.

For each algorithm, multiple candidate values of k (number of clusters) were tested. The goal is to identify the optimal number of clusters for each algorithm by balancing internal validation measures and external measures. The best-performing k is selected separately for KMeans and Hierarchical clustering, ensuring that each algorithm was assessed under its most favorable conditions.

3.1. External Evaluation Metrics

External metrics compare clusters to the RFM-based labels, which serve as a domain-specific reference. They are particularly important because the objective is not only to generate statistically valid clusters, but also to ensure alignment with the segmentation framework that marketers already recognize and use. These external measures evaluate alignment with RFM segments purely from an interpretability standpoint. They do not assume that RFM represents an optimal or correct segmentation; rather, they quantify how easily the ML-derived structure can be mapped onto business-recognized categories. This distinction ensures that the evaluation captures interpretability alignment rather than treating RFM as a ground-truth label.

3.1.1. Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)

The ARI measures the degree of agreement between two partitions, while correcting for agreements that would occur by chance (

Hubert & Arabie, 1985). Given a contingency table where

a is the number of pairs of points in the same cluster in both partitions,

b the number of pairs in the same cluster in one partition but not the other, and so on, ARI is defined as:

where RI is the Rand Index.

ARI is a widely accepted measure for evaluating clustering against ground truth because it corrects for randomness. This makes it especially useful for assessing whether data-driven clusters truly capture business-defined segments rather than matching them accidentally. Values range from (−1) (worse than random) to 1 (perfect match), with 0 representing chance-level performance.

3.1.2. Normalized Mutual Information (NMI)

NMI measures the mutual dependence between two label assignments U (RFM labels) and V (cluster labels) (

Strehl & Ghosh, 2002).

where

is mutual information and H(⋅) is entropy.

Unlike ARI, which is based on pair counting, NMI is an information-theoretic measure. It provides a complementary view by quantifying how much “information” the clusters preserve about the RFM labels. NMI ranges from 0 (no mutual information) to 1 (perfect agreement).

3.1.3. Homogeneity, Completeness, and V-Measure

These metrics are intuitive for business users because they capture purity and consistency of groupings, both of which matter in practice. For instance, a marketing campaign requires both homogeneous targeting and complete coverage of a segment.

3.2. Internal Evaluation Metrics

Internal metrics examine the quality of clusters based on the data distribution itself, without reference to RFM labels. They ensure that clusters are compact and well-separated—properties that typically make them meaningful in statistical terms.

3.2.1. Silhouette Coefficient

The Silhouette score (

Rousseeuw, 1987) evaluates how similar a point is to its own cluster compared to other clusters:

where

is the mean intra-cluster distance, and

the mean nearest-cluster distance.

It is intuitive and directly interpretable. A high silhouette score means customers are well-matched to their cluster and far from others—a desirable property for actionable segmentation. Ranges from −1 (misclassified points) to 1 (well-separated clusters), with values above 0.5 generally considered strong.

3.2.2. Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI)

The DBI (

Davies & Bouldin, 1979) measures the average “similarity” between each cluster and its most similar neighbor, based on within-cluster scatter and between-cluster distances:

where

is the distance between centroids.

The DBI is the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar one. For cluster with centroid , and cluster scatter . Lower DBI values indicate better clustering, with 0 representing perfectly separated clusters.

3.3. Selection and Alignment

The evaluation procedure follows a structured two-stage process. In the first stage, candidate solutions are generated for k ∈ {5,6,…,12} for both KMeans and Hierarchical clustering. Cluster selection is treated as a multi-objective optimization problem balancing cluster compactness, separation, and interpretability. Internal quality is assessed through the Silhouette Coefficient (higher values indicate tighter and more separated clusters) and the Davies–Bouldin Index (lower values indicate better separation). For Hierarchical clustering, the structural patterns observed in the dendrogram are also considered to ensure that the chosen solution aligns with the natural hierarchical organization of the dataset.

In the second stage, once the best-performing k is identified separately for each algorithm, both internal and external validation metrics are computed on the corresponding partitions. External evaluation (ARI, NMI, Homogeneity, Completeness, and V-measure) quantified alignment with RFM-based labels, while internal measures validated structural robustness.

Finally, the selected partitions are aligned with RFM-based groups using the Hungarian algorithm (

Kuhn, 1955). The algorithm enforces a one-to-one correspondence between machine-generated clusters and rule-based segments, enabling the results to be interpreted in terms familiar to marketing and credit risk professionals.

To balance internal and external validity and provide a single point of comparison, we compute an aggregate performance score (). All metrics are normalized to a scale between 0 and 1, with DBI inverted since lower is better and aggregated into a composite score. Depending on business priorities, higher weights can be assigned to either internal quality (cluster compactness and separation) or external alignment (agreement with established RFM structures).

Through this combined evaluation and alignment process, the chosen clustering solution maintains statistical validity while remaining interpretable and actionable within financial-services segmentation workflows.

The Hungarian alignment step therefore does not enforce replication of RFM logic. Instead, it provides a consistent reference frame that enables analysts to interpret divergences between heuristic and data-driven segmentations, highlighting areas where customer behavior deviates from rule-based expectations.

3.4. Computational Efficiency

Computational efficiency is also evaluated by recording total execution times for each clustering method at their respective optimal k. This assessment excludes preprocessing to provide a focused comparison of algorithmic efficiency. Thus, the analysis highlights not only the segmentation quality but also the computational trade-offs between partition-based and agglomerative methods when applied to large-scale customer datasets (

Xu & Wunsch, 2005).

4. Research Results and Analysis

4.1. Establishing the RFM Baseline

As a reference point for evaluating machine learning–based segmentation, we use rule-based RFM frameworks developed by business experts. These frameworks group customers based on their Recency, Frequency, and Monetary scores into interpretable categories. Depending on the level of detail required, businesses often maintain several versions of such segmentations, ranging from relatively coarse divisions with five groups to more detailed structures with up to twelve groups.

Rather than fixing one version of RFM segmentation in advance, we treat all available frameworks as candidate baselines. Once the best-performing clustering approach (KMeans or hierarchical) and its optimal number of clusters are identified, we select the RFM segmentation with the same number of groups. This ensured a fair, one-to-one comparison between rule-based and data-driven segmentations.

This approach ensures that the RFM baseline is not arbitrarily chosen but instead aligned with the structure revealed by unsupervised clustering.

4.2. KMeans Clustering Evaluation

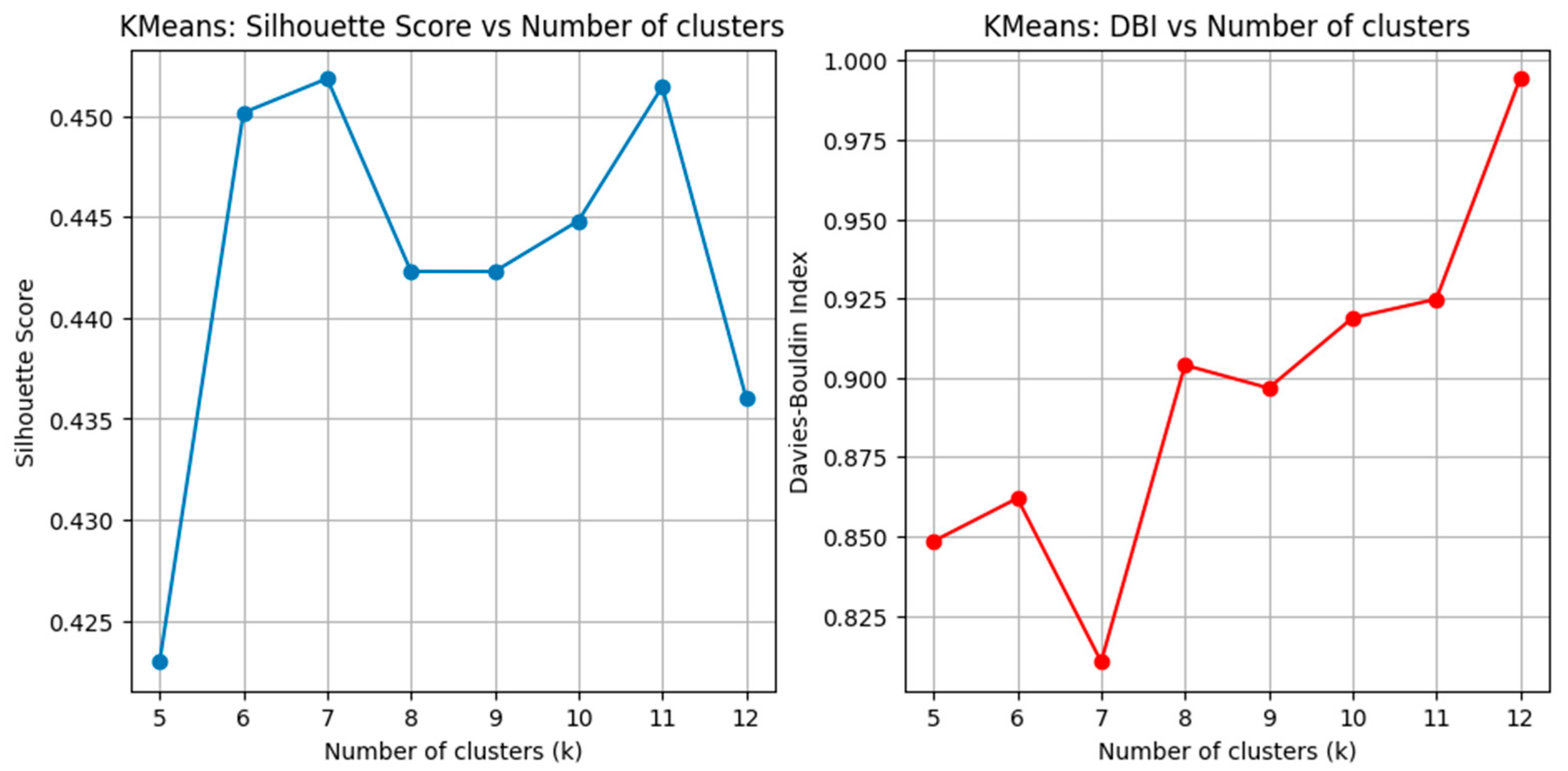

KMeans clustering is applied to the dataset with the number of clusters varying from k = 5 to k = 12, ensuring comparability with the available RFM-based segmentations. It is executed with 20 random initializations and fixed random seeds to ensure reproducibility, with cluster selection based on the lowest inertia outcome The performance of each clustering solution, shown in

Table 1, is evaluated using two internal validation metrics: The Silhouette Score and the DBI.

Silhouette values shows consistent performance across the tested range, peaking at k = 7 with a score of 0.452 (

Figure 2). This result suggests that the seven-cluster solution produced the most compact and well-separated groupings. At lower values, such as k = 5 (Silhouette = 0.423), the clusters were broader and less distinct. Similarly, at higher values, such as k = 12 (Silhouette = 0.436), the score declined slightly, reflecting fragmentation of groups.

The DBI, which penalizes overlap and measures within-cluster similarity relative to between-cluster separation, further supports this finding (

Figure 2). The lowest DBI is observed at k = 7 (DBI = 0.810), indicating reduced similarity between clusters and strong inter-cluster separation. In contrast, smaller or larger numbers of clusters lead to higher DBI values, such as 0.848 at k = 5 and 0.994 at k = 12, which reflect less efficient separation.

Taken together, the results indicate that KMeans achieved its best performance at k = 7, which is selected as the optimal solution for further alignment and comparison with RFM segmentation.

4.3. Hierarchical Clustering Evaluation

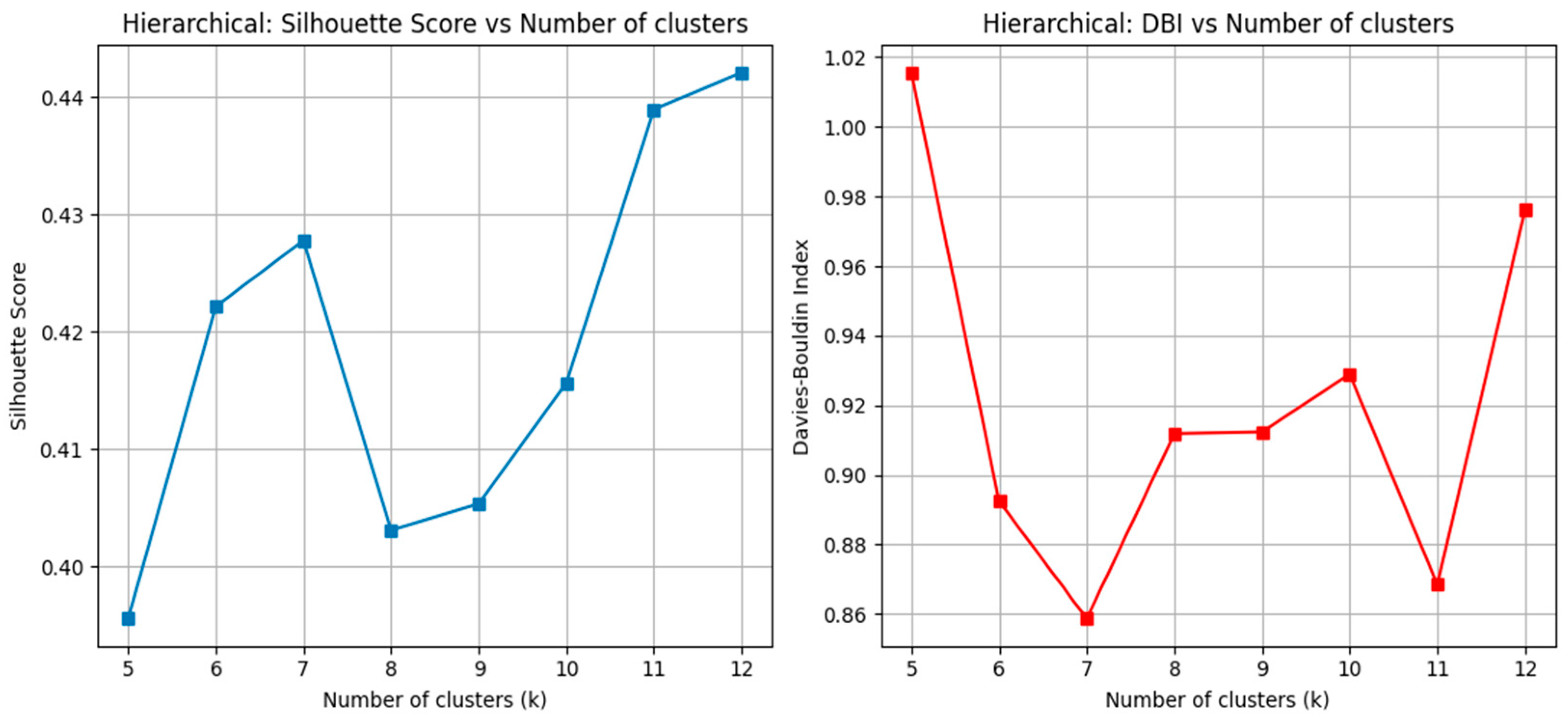

Hierarchical agglomerative clustering with Ward’s linkage is applied to the same dataset, with the number of clusters varied between k = 5 and k = 12. The evaluation follows the same two internal measures: The Silhouette Score and the DBI (

Table 2).

The Silhouette analysis shows steady improvements (

Figure 3) as the number of clusters increased, reaching its highest value at k = 12 (Silhouette = 0.442). In contrast, lower values of k, such as 5 or 6 clusters, yield weaker performance, suggesting insufficient separation of behavioral patterns at coarser levels of granularity.

The DBI results provide complementary insight (

Figure 3). While the lowest DBI value is observed at k = 7 (DBI = 0.859), several configurations—including k = 11 and k = 12—achieve comparably strong separation. These results indicate that cluster compactness does not deteriorate substantially at higher values of k, even though the DBI does not continue to decrease monotonically.

Model selection must also consider business interpretability and behavioral granularity (

Table 3). Although several values of k exhibit competitive internal validity, the 12-cluster solution represents the most appropriate choice for practical segmentation use cases in financial services. Internally, k = 12 achieves the highest Silhouette Coefficient (0.442), indicating strong consistency of assignment and meaningful separation between behavioral profiles. Although the DBI is not minimal at this level, its value (0.976) remains within an acceptable range and does not indicate significant cluster overlap.

In addition to internal metrics, more granular segmentations often provide superior operational utility. With twelve clusters, meaningful behavioral differences become visible—particularly among subgroups that share similar recency or frequency characteristics but differ substantially in ROI or engagement patterns. These distinctions are highly relevant for reactivation, dormant-portfolio management, and targeted communication strategies. For these reasons, k = 12 offers the best balance between statistical validity, differentiation of behavioral patterns, and the practical demands of real-world customer segmentation.

4.4. Cluster Alignment

4.4.1. Alignment Evaluation

To ensure a meaningful comparison between machine learning-based clustering and the baseline RFM segmentations, we apply a cluster alignment procedure. Since unsupervised methods assign cluster labels arbitrarily, direct one-to-one comparisons with predefined RFM groups are not possible without alignment. To address this, the Hungarian algorithm is applied to align the machine-generated clusters with RFM-defined categories. This step ensures that each data-driven cluster is optimally mapped to the most similar RFM segment, allowing for a fair evaluation using both external and internal metrics.

After alignment, the evaluation is carried out using both external and internal validation metrics. External measures such as the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) quantify how well the machine learning clusters reproduce the structure implied by the RFM framework. Internal measures, including the Silhouette Score and the DBI, assess the compactness and separation of the clusters themselves. In addition, homogeneity, completeness, and the V-measure were used to capture the trade-off between cluster purity and coverage (

Table 4).

The results show distinct patterns between the two methods. For the KMeans solution at k = 7, the alignment results show modest agreement with the RFM baseline. The ARI = 0.253 and NMI = 0.495 indicate partial correspondence between the rule-based and machine-learned partitions. Internal evaluation further confirms moderate structural quality, with a Silhouette Score of 0.452 and a DBI of 0.810. The homogeneity (0.531), completeness (0.464), and V-measure (0.495) also suggest that the KMeans clusters captured some, but not all, of the behavioral distinctions reflected in RFM.

The Hierarchical clustering solution at k = 12 performs more strongly in terms of alignment with RFM. External metrics show higher consistency, with ARI = 0.416 and NMI = 0.652, while internal measures suggest well-separated clusters (Silhouette = 0.442). Although the DBI is slightly higher (0.976), the results indicate a good balance between cohesion and separation. The homogeneity (0.686), completeness (0.622), and V-measure (0.652) further support the conclusion that Hierarchical clustering produces clusters more consistent with RFM-defined categories.

The results for both segmentations using the aggregated performance score (

, introduced in

Section 3.3. Selection and Alignment, are as follow:

This indicates that while KMeans formed slightly more compact clusters, Hierarchical clustering offered a superior balance between statistical robustness and alignment with established business segmentation practices. Therefore, the study concludes that Hierarchical clustering with 12 clusters provides the more effective segmentation strategy. This approach not only delivers statistically sound clusters but also ensures that the resulting groups remain interpretable and actionable within the business context, making it the recommended method for practical deployment.

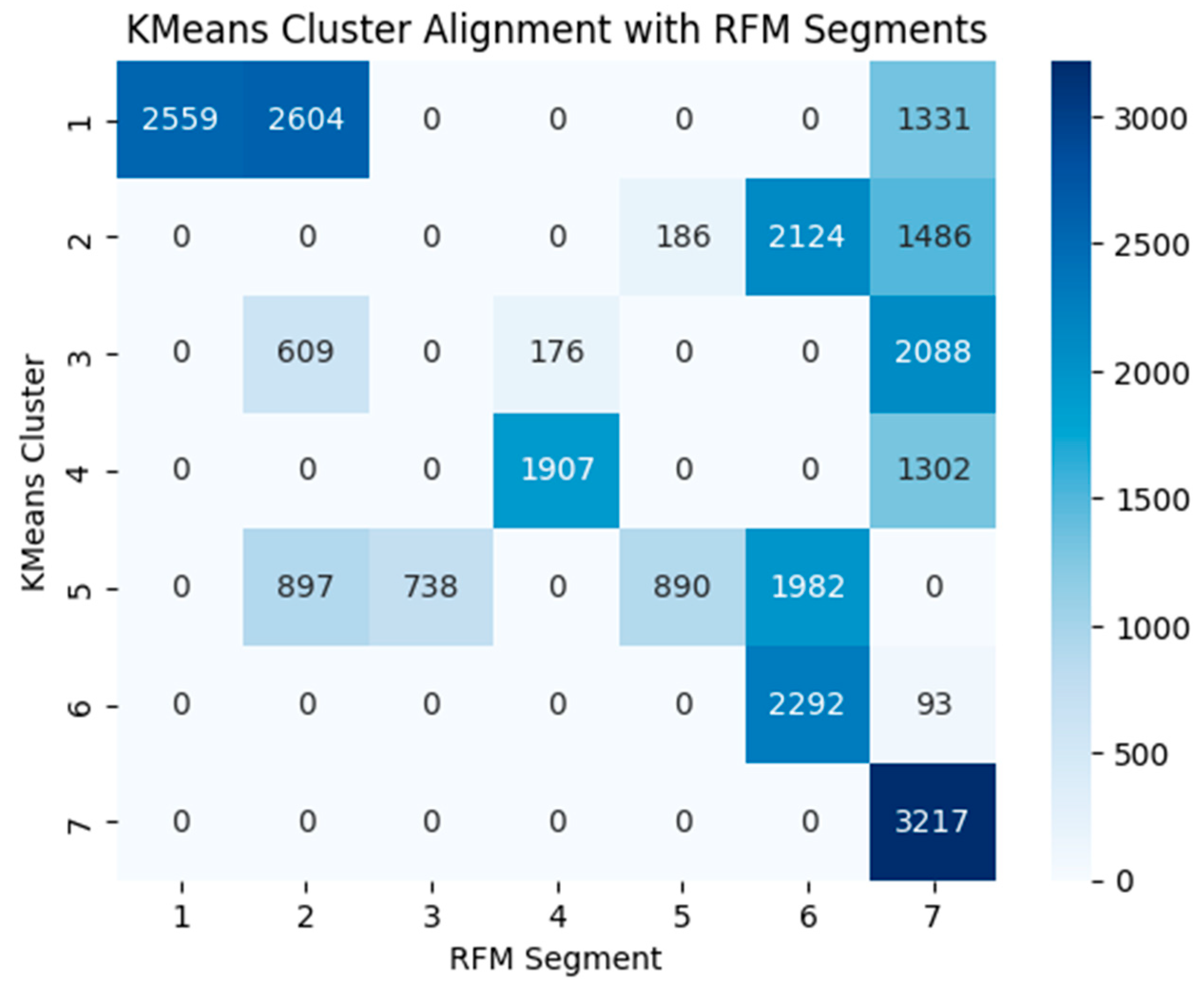

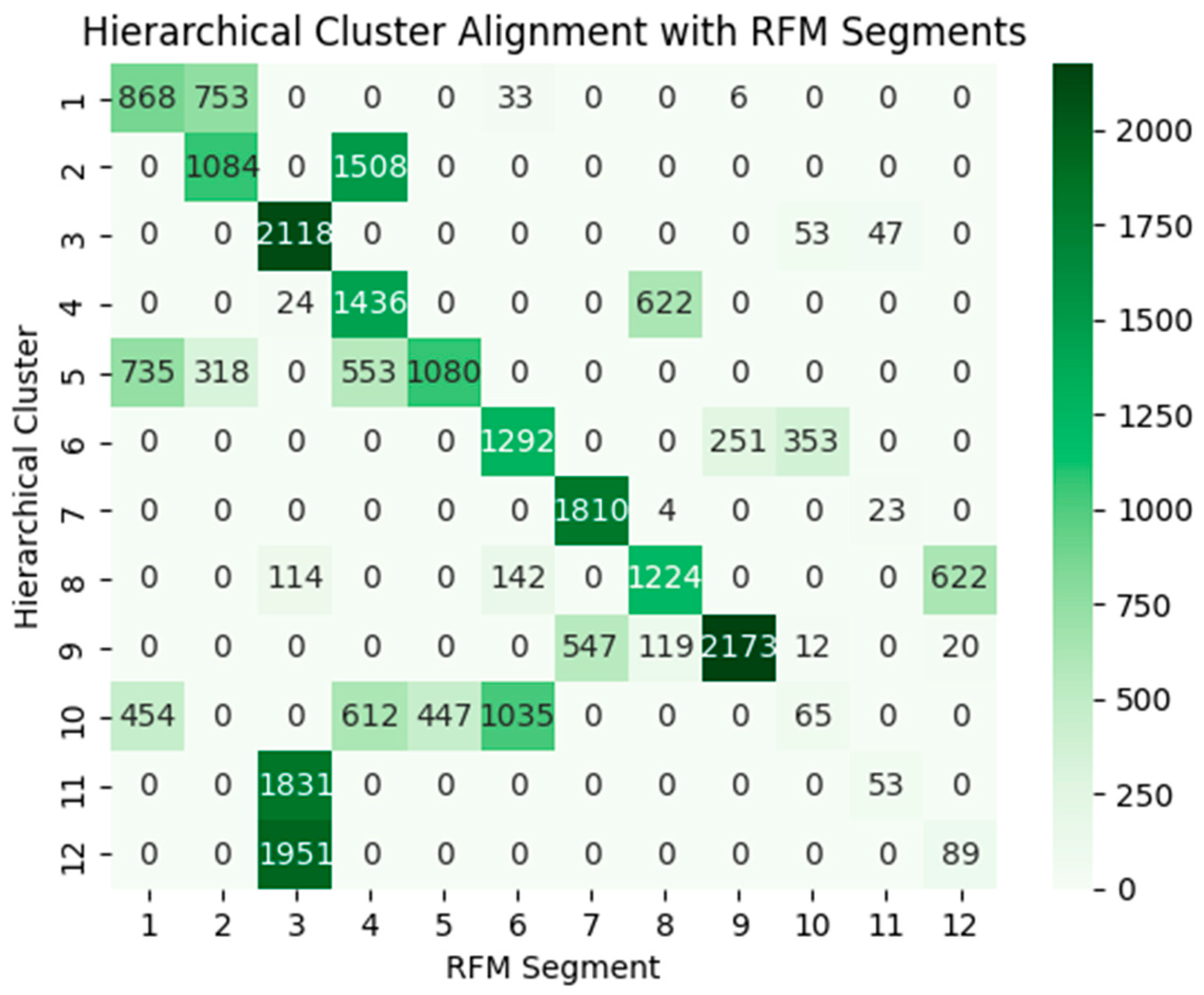

To complement the external validity metrics and the aggregate performance score (APS), we also provide heatmap visualizations of the alignment matrices. These plots make the structural differences between the two algorithms directly observable, showing the degree of concentration within aligned groups and the extent of cross-segment mixing. The resulting alignment structures are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

The heatmaps provide visual evidence of the structural differences between the clustering approaches. In the KMeans solution, the absence of a strong diagonal pattern reveals that several RFM categories are distributed across multiple clusters, and conversely, individual KMeans clusters contain mixtures of different RFM groups. This dispersion suggests that KMeans identifies partitions that do not closely reflect the behavioral boundaries implied by RFM scoring, thereby limiting interpretability. In contrast, the hierarchical clustering heatmap exhibits distinct, high-density diagonal blocks, indicating that each hierarchical cluster aligns predominantly with a single RFM segment. This structure highlights two key properties of the hierarchical solution: (1) clusters are behaviorally coherent and internally consistent, and (2) the segmentation granularity at k = 12 captures meaningful distinctions that are both data-driven and interpretable. The emergence of these well-defined block structures provides strong visual support for selecting 12 clusters in the hierarchical framework and complements the quantitative validity and alignment metrics reported earlier.

The experiments reveal a clear contrast in computational cost. KMeans complete the clustering process in approximately 49.229 s, while Hierarchical clustering requires 96.657 s under identical conditions. While these differences are manageable in small to medium datasets, they may become critical when scaling to millions of customer records in operational environments.

4.4.2. Behavioral Divergences and Cluster Profiles

Several systematic divergences arise that offer insight into underlying behavioral patterns.

Some RFM groups contain substantial variation in recency, frequency, and monetary metrics. For example, “Potential Loyalists” comprise 24 distinct scores, spanning wide behavioral differences. Hierarchical clustering redistributes these customers into four more coherent clusters, revealing heterogeneity masked by threshold-based segmentation.

- 2.

Multiple RFM categories merge into a single ML-driven behavioral group.

ML Cluster 1 (aligned to “Champions”) includes high-value scores such as 555 and 545, but also customers originally labeled “At Risk” or “Cannot Lose Them But Losing” (e.g., 255, 155). Despite differing RFM assignments, these customers share high monetary value and strong behavioral similarity, explaining their consolidation.

- 3.

RFM categories that appear homogeneous split into multiple ML clusters.

Segments like “Lost Customers” are divided into ML clusters 8, 9, and 12. These clusters represent distinct forms of dormancy and low engagement that the rule-based system cannot distinguish.

- 4.

Small threshold-based differences disappear under ML clustering.

Scores such as 331, 341, 351, and 352—assigned to different RFM groups—are placed together in ML Cluster 4, reflecting that their underlying behaviors are near-identical despite categorical boundaries.

Together, these divergences demonstrate that Hierarchical clustering both merges RFM groups artificially split by thresholds and splits RFM groups that aggregate behaviorally distinct customers, thereby revealing latent structure in repayment behavior.

Table 5 summarizes the behavioral characteristics of each ML cluster following Hungarian alignment. Each cluster is interpreted based on:

- (1)

The RFM segment whose centroid is most similar;

- (2)

The set of underlying RFM score codes it contains, and;

- (3)

The behavioral meaning emerging from continuous recency, frequency, and monetary variables.

Aligned RFM labels support interpretation, but clusters retain their own structure. Rather, the alignment simply identifies the RFM segment whose average behavior is closest to that of each machine-learned cluster. This helps with interpretation, but it does not imply that the data-driven clusters recreate the original RFM segments. The machine-learning solution still reflects its own structure and uncovers patterns that the rule-based RFM approach may miss.

4.5. Practical and Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, the findings have several important implications for financial services, customer re-engagement and marketing strategy.

First, the results demonstrate that relying exclusively on rule-based RFM segmentation provides a high degree of interpretability but may overlook meaningful behavioral nuances in customer data. Automated clustering methods—particularly Hierarchical clustering combined with alignment—identify more coherent and granular behavioral structures. This enables organizations to move beyond fixed threshold-based categories and adopt dynamic, data-driven segments while still retaining the familiarity and transparency of RFM.

Second, the choice of segmentation method should be guided by operational objectives. For applications requiring speed and computational efficiency, such as real-time campaign targeting, KMeans may be preferable. In contrast, for strategic tasks where explainability, traceability, and segmentation stability are essential—such as dormant portfolio monitoring or early risk detection—Hierarchical clustering provides stronger alignment with interpretable behavioral patterns and may therefore support more actionable decision-making.

Third, the Hungarian alignment step plays a critical role in ensuring that machine-learned clusters remain business-friendly. Without alignment, algorithmic clusters may appear opaque or difficult to relate to established segmentation frameworks. By mapping machine-derived structures into the familiar language of RFM categories, the approach preserves interpretability and facilitates communication between technical analysts, marketing teams, and credit managers. This alignment also highlights where data-driven patterns reinforce existing assumptions and where they suggest potential refinements to business heuristics.

Finally, improved segmentation quality has potential downstream economic benefits. More precise grouping of customers can enhance targeting efficiency, reduce acquisition and contact costs, support more effective retention and reactivation strategies, and help identify behavioral changes that may signal emerging credit risk. Although outcome-based validation is not yet available, the framework establishes a systematic and reproducible basis for improved decision-making once response and performance data become accessible.

4.6. Limitations

As the segmentation framework has not yet been implemented in a live operational environment, no empirical outcome data—such as customer reactivation response rates, post-intervention repayment performance, or realized profitability—are currently available. Accordingly, quantitative economic validation cannot yet be undertaken. Although the proposed methodology demonstrates strong internal validity and interpretability, the absence of historical performance indicators precludes direct assessment of financial impact or return on application. The system is presently entering initial deployment under cold-start conditions, and outcome observations will only emerge once segmentation-driven interventions are executed in practice. Future research should therefore incorporate realized behavioral and financial outcomes as they become available, providing a foundation for rigorous ex-post evaluation of economic efficacy and business value.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of machine learning-based clustering methods—specifically KMeans and Hierarchical clustering—as extensions of traditional RFM segmentation. By applying the Hungarian algorithm to align machine-generated clusters with RFM segments, the framework enables interpretability while allowing segmentation to be driven by the underlying data structure.

The results show that Hierarchical clustering provides stronger alignment with RFM behavioral patterns and better supports segmentation tasks where explainability and stability are essential. KMeans offers faster execution and efficient performance but produces clusters that align less closely with interpretable behavioral categories. The alignment process provides a coherent reference frame for comparing machine-learned clusters to familiar business segments, helping analysts understand where algorithmic insights reinforce or diverge from existing segmentation logic.

The findings demonstrate that automated clustering can uncover meaningful behavioral distinctions that are not fully captured by threshold-based RFM scoring. Rather than replicating RFM categories, the machine-learning approach highlights latent patterns in repayment behavior and supports more nuanced segmentation for dormant-portfolio monitoring and customer re-engagement strategies.

Future work should incorporate additional behavioral or contextual variables and evaluate the financial impact of the segmentation once outcome data become available. As operational deployment progresses, measuring changes in campaign performance, customer activation rates, or portfolio profitability will allow for a more comprehensive assessment of business value.

Overall, the study shows that traditional RFM segmentation can be effectively complemented by automated clustering within an interpretable and reproducible workflow, offering a practical path toward more data-driven customer segmentation in financial services.