The Influence of Investor Sentiment on the South African Property Market: A Comparative Assessment of JSE Indices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Conceptualization

2.2. Empirical Review

2.2.1. Investor Sentiment and Property Markets

2.2.2. Empirical Methodologies

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Context

3.2. Empirical Study

3.2.1. Secondary Data

Property Variables Used

- FTSE/JSE Property indices

- JSE SA REIT (J803)—JSE REIT

- 2.

- JSE SA Listed Property (J253)—JSE LIST

- 3.

- JSE Capped Property Index (J254)—JSE CAP

- 4.

- JSE Real Estate Investment and Services—JSE RIS

Investor Sentiment Proxies

Market Proxy

3.3. Empirical Model

3.3.1. Principle Component Analysis

3.3.2. VAR Model

3.3.3. Granger Causality Test

3.3.4. Preliminary and Diagnostic Tests

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Preliminary Tests

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Unit Root and Stationarity Test

4.1.3. Johansen Cointegration Test

4.2. Empirical Model Results

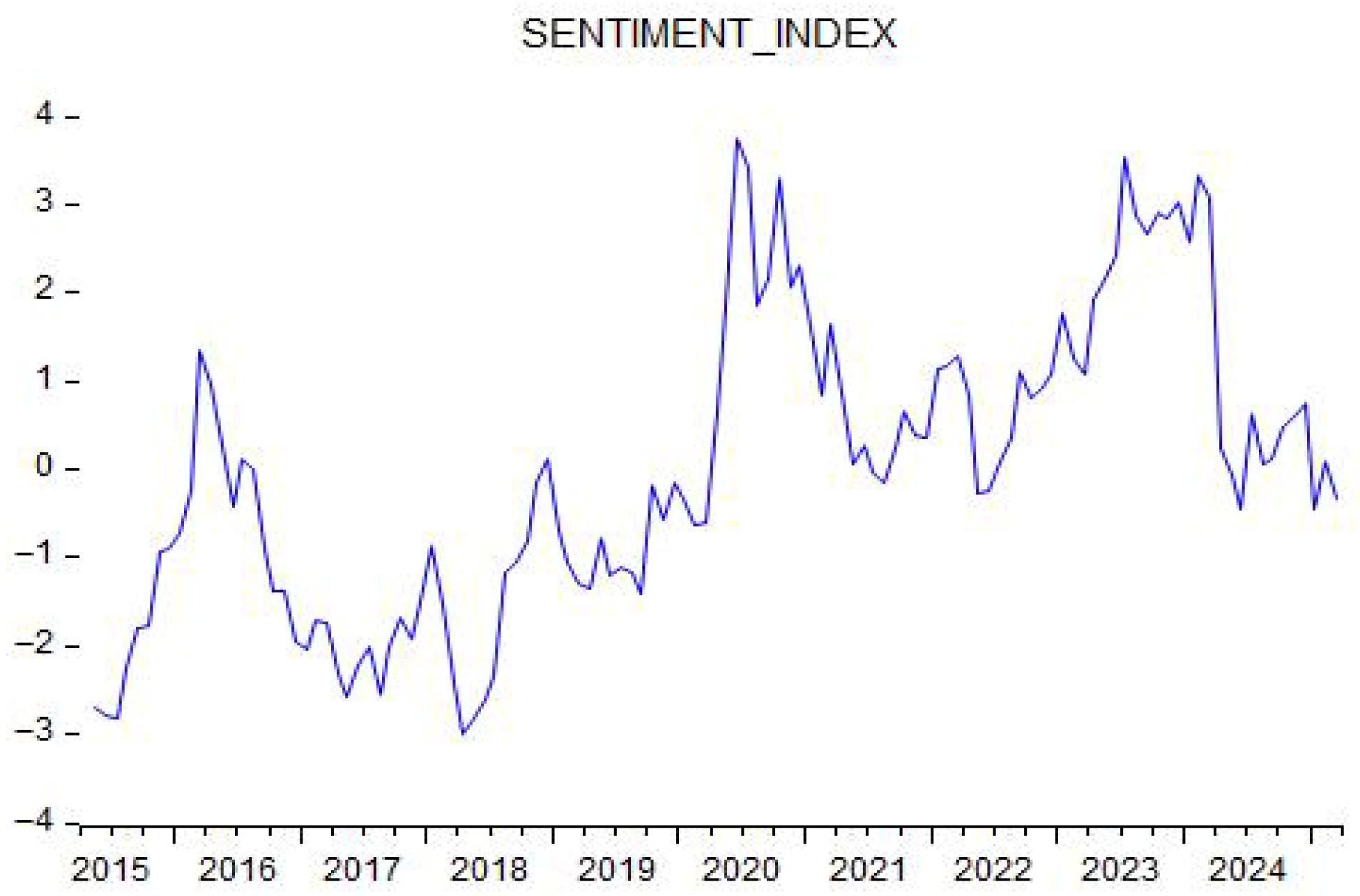

4.2.1. Investor Sentiment Index Estimation

4.2.2. Pre Diagnostic Checks

4.2.3. Empirical Models

Vector Error Correction Model (VECM)

Granger Causality Test (VEC Granger Causality/Block Exogeneity Wald Test)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Panel A: Eigenvalues: (Sum = 7, Average = 1) | |||||||

| Number | Value | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative Value | Cumulative Proportion | ||

| 1 | 2.759044 | 1.491149 | 0.3941 | 2.759044 | 0.3941 | N/A | |

| 2 | 1.267895 | 0.222811 | 0.1811 | 4.026939 | 0.5753 | ||

| 3 | 1.045084 | 0.213692 | 0.1493 | 5.072023 | 0.7246 | ||

| 4 | 0.831392 | 0.058766 | 0.1188 | 5.903415 | 0.8433 | ||

| 5 | 0.772626 | 0.597396 | 0.1104 | 6.676041 | 0.9537 | ||

| 6 | 0.175230 | 0.026501 | 0.0250 | 6.851271 | 0.9788 | ||

| 7 | 0.148729 | --- | 0.0212 | 7.000000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Panel B: Eigenvectors (Loadings): | |||||||

| Variable | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 3 | PC 4 | PC 5 | PC 6 | PC 7 |

| ADV_DEC | 0.159590 | 0.551357 | −0.317095 | 0.057448 | 0.751270 | 0.046014 | −0.012774 |

| CCI | −0.295229 | −0.379980 | 0.449431 | 0.445785 | 0.477187 | 0.357374 | 0.110992 |

| CNN | −0.028165 | 0.433369 | 0.726884 | −0.491142 | 0.033926 | 0.028746 | 0.199598 |

| EQ_ISSUE | −0.164714 | 0.558361 | 0.127696 | 0.698636 | −0.365515 | −0.116657 | 0.097437 |

| R_DBIDASK | 0.532316 | −0.219986 | 0.135666 | 0.179280 | 0.134443 | −0.540217 | 0.554788 |

| SAVI | 0.551154 | 0.057079 | −0.064794 | 0.061318 | −0.232075 | 0.746194 | 0.272669 |

| STURN | 0.521839 | −0.019842 | 0.360821 | 0.181000 | 0.034642 | −0.084209 | −0.745685 |

| Panel A: Eigenvalues: (Sum = 7, Average = 1) | |||||||

| Number | Value | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative Value | Cumulative Proportion | ||

| 1 | 2.771956 | 1.522375 | 0.3960 | 2.771956 | 0.3960 | N/A | |

| 2 | 1.249581 | 0.202118 | 0.1785 | 4.021536 | 0.5745 | ||

| 3 | 1.047463 | 0.210442 | 0.1496 | 5.068999 | 0.7241 | ||

| 4 | 0.837021 | 0.063459 | 0.1196 | 5.906020 | 0.8437 | ||

| 5 | 0.773562 | 0.601193 | 0.1105 | 6.679582 | 0.9542 | ||

| 6 | 0.172368 | 0.024319 | 0.0246 | 6.851950 | 0.9789 | ||

| 7 | 0.148050 | --- | 0.0211 | 7.000000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Panel B: Eigenvectors (Loadings): | |||||||

| Variable | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 3 | PC 4 | PC 5 | PC 6 | PC 7 |

| CNN | −0.025067 | 0.444861 | 0.715808 | −0.498449 | 0.019605 | 0.044877 | 0.195550 |

| STURN | 0.520453 | −0.016591 | 0.361568 | 0.177715 | 0.042220 | −0.135893 | −0.739114 |

| R/$BID_ASK | 0.533061 | −0.210381 | 0.139666 | 0.178329 | 0.138715 | −0.501307 | 0.591377 |

| SAVI | 0.550796 | 0.045326 | −0.063972 | 0.066208 | −0.228616 | 0.765821 | 0.217593 |

| CCI | −0.297930 | −0.361588 | 0.456958 | 0.435143 | 0.495586 | 0.358943 | 0.088807 |

| EQ_ISSUE | −0.159991 | 0.566635 | 0.119893 | 0.702350 | −0.353256 | −0.103316 | 0.100964 |

| ADV_DEC | 0.163125 | 0.551079 | −0.331819 | 0.033700 | 0.745608 | 0.047064 | −0.017786 |

References

- Ashraf, B. N. (2020). Stock markets’ reaction to COVID-19: Cases or fatalities? Research in International Business and Finance, 54, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asteriou, D., & Hall, S. G. (2023). Applied econometrics (4th ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M., & Stein, J. C. (2004). Market liquidity as a sentiment indicator. Journal of Financial Markets, 7, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, F., & Zouaoui, M. (2013). Measuring stock market investor sentiment. Journal of Applied Business Research, 29(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, D., Gopi, Y., & Tshivhinda, J. (2015). The role of South African property in balanced portfolios. South African Journal of Accounting Research, 29(1), 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. W., & Cliff, M. T. (2004). Investor sentiment and the near-term stock market. Journal of Empirical Finance, 11, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K. S., & Lee, J. (2021). The effect of sentiment on commercial real estate returns: Investor and occupier perspectives. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 39(6), 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S. L., & Tsai, M. S. (2023). Analyses for the effects of investor sentiment on the price adjustment behaviors for stock market and REIT market. International Review of Economics & Finance, 86, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J., Ling, D. C., & Naranjo, A. (2008). Commercial real estate valuation: Fundamentals versus investor sentiment. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 38, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, A., & Flint-Hartle, S. (2003). A bounded rationality framework for property investment behaviour. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 21(3), 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallimore, P., & Gray, A. (2002). The role of investor sentiment in property investment decisions. Journal of Property Research, 19(2), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengelbrock, J., Theissen, E., & Westheide, C. (2013). Market response to investor sentiment. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 40(7–8), 901–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E. C. M., Dong, Z., Jia, S., & Lam, C. H. L. (2017). How does sentiment affect returns of urban housing? Habitat international, 64, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investing.com. (2025). FTSE/JSE real estate investment and services. Available online: https://www.investing.com/indices/ftse-jse-re-investment-and-services (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- JSE (Johannesburg Stock Exchange). (2017). Property. Available online: https://www.jse.co.za/property (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Junaeni, I. (2020). Analysis of factors that influence decision making invest in capital markets in millennial generations. International Journal of Accounting & Finance in Asia Pacific, 3(3), 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. (2017). Practical guide to principal component methods in R: PCA, M (CA), FAMD, MFA, HCPC, factoextra (Vol. 2). Sthda. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, A. B., & Murphree, E. S. (1987). A comparison of the Akaike and schwarz criteria for selecting model order. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series, 37(2), 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakye, B., & Chan, T. H. (2025). Market sentiment in emerging economies: Evidence from the South African property market. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 18(3), 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. H. L., & Hui, E. C. M. (2018). How does investor sentiment predict the future real estate returns of residential property in Hong Kong? Habitat International, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J. S. (1992). An introduction to prospect theory. Political Psychology, 13(2), 171–186. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3791677 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Leybourne, S., & Newbold, P. (2002). On the size properties of Phillips-Perron Tests. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 20(1), 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Y., Rahman, H., & Yung, K. (2008). Investor sentiment and REIT returns. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 39, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D. C., Naranjo, A., & Scheick, B. (2010). Investor sentiment and asset pricing in public and private markets. RERI WP, 170, 1–48. Available online: https://www.reri.org/research/article_pdf/wp170.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Ling, D. C., Naranjo, A., & Scheick, B. (2014). Investor sentiment, limits to arbitrage and private market returns. Real Estate Economics, 42(3), 531–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D. C., Ooi, J. T. L., & Le, T. T. T. (2015). Explaining house price dynamics: Isolating the role of nonfundamentals. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 47(1), 87–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. H., Dai, S. R., Chang, F. M., Lin, Y. B., & Lee, N. R. (2020). Does the investor sentiment affect the stock returns in Taiwan’s stock market under different market states? Journal of Applied Finance and Banking, 10(5), 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lowies, G. A., Hall, J. H., & Cloete, C. E. (2015). The role of market fundamentals versus market sentiment in property investment decision-making in South Africa. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 23(2), 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowies, G. A., Hall, J. H., & Cloete, C. E. (2016). Heuristic-driven bias in property investment decision-making in South Africa. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 34(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, K., Pieterson, J., & Rajab, P. (2025). The quantitative research process. In K. Maree (Ed.), First steps in research (pp. 206–218). Van Schaik Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Messaoud, D., & Ben Amar, A. (2025). Herding behaviour and sentiment: Evidence from emerging markets. EuroMed Journal of Business, 20(2), 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, F., Ferreira-Schenk, S., & Matlhaku, K. (2024). Effect of market-wide investor sentiment on South African government bond indices of varying maturities under changing market conditions. Economies, 12(10), 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, F., Ferreira-Schenk, S., & Matlhaku, K. (2025a). Determinants of South African asset market co-movement: Evidence from investor sentiment and changing market conditions. Risks, 13(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, F., Ferreira-Schenk, S., & Matlhaku, K. (2025b). The effects of investor sentiment on stock return indices under changing market conditions: Evidence from South Africa. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(2), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muguto, H. T., Rupande, L., & Muzindutsi, P. F. (2019). Investors sentiment and foreign financial flows: Evidence from South Africa. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci, 37(2), 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N. M. N., & Maheran, N. (2009). Behavioural finance vs. traditional finance. Advance Management Journal, 2(6), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Muzindutsi, P. F., Apau, R., Muguto, L., & Muguto, H. T. (2023). The impact of investor sentiment on housing prices and the property stock index volatility in South Africa. Real Estate Management and Valuation, 31(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. T., Tuan Nguyen, A., & Nguyen, D. T. (2024). The growth of the real estate corporate bond market in Vietnam: The role of investor sentiment. Review of Behavioral Finance, 16(4), 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokora, Z., Pak, A., & Pelizzo, R. (2024). The conditional effects of party system change on economic growth in Africa. Acta Politica, 27, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). Consumer Confidence Index (BCI). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/consumer-confidence-index-cci.html (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Oladeji, J., Yacim, J., Wall, K., & Zulch, B. (2020). Macroeconomic leading indicators of listed property price movements in Nigeria and South Africa. Acta Structilia, 27(2), 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q., Pham, H., Pham, T., & Tiwari, A. K. (2025). Revisiting the role of investor sentiment in the stock market. International Review of Economics & Finance, 100, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. L., & Shamsuddin, A. (2019). Investor sentiment and the price-earnings ratio in the G7 stock markets. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 55, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, N., & Missaoui, S. (2015). Role of investor sentiment in financial markets: An explanation by behavioural finance approach. International Journal of Accounting and Finance, 5(4), 362–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupande, L., Muguto, H. T., & Muzindutsi, P. F. (2019). Investor sentiment and stock return volatility: Evidence from the Johannesburg stock exchange. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1600233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M., & Bhardwaj, R. S. (2021). Literature review of behavioral finance: Then and now. Elementary Education Online, 20(1), 2782. [Google Scholar]

- Saydometov, S., Sabherwal, S., & Aroul, R. R. (2020). Sentiment and its asymmetric effect on housing returns. Review of Financial Economics, 38(4), 580–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1982). The expected utility model: Its variants, purposes, evidence and limitations. Journal of Economic Literature, 20(2), 529–563. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2724488 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Shiller, R. J. (2003). Measuring bubble expectations and investor confidence. The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 1(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. (1972). Theories of bounded rationality. Decision and Organization, 1(1), 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, C. A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica, 48(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Market/Asset Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Muzindutsi et al. (2023) | South African property market; small and medium housing segments; South African Listed Property Index (J253) | Significant positive effect of sentiment on returns, especially in small/medium house segments. Volatility decreases with positive sentiment. |

| Lowies et al. (2015) | SA property fund managers | Market fundamentals hold greater significance than sentiment. However, when fundamental information is incomplete, managers rely on “personal and private network sources”. |

| Lin et al. (2008) | US REIT market | Investor sentiment has a significant positive effect on REIT returns; this is also true under different conditions. |

| Kwakye and Chan (2025) | SA housing market | Market sentiment has a limited influence on the South African property market. Cointegration evident in the long run. |

| Lam and Hui (2018) | Hong Kong residential property | There is a negative relationship between investor sentiment and housing prices in Hong Kong. |

| Nguyen et al. (2024) | Vietnam real estate corporate bond market | Real estate market sentiment has a positive impact on real estate corporate bond market, while stock market sentiment has a negative impact. |

| Cheung and Lee (2021) | Commercial real estate returns in Australia | Investor and occupier sentiments affect real estate returns differently; however, the effect is evident. Market-specific sentiment has a “significant impact on commercial real estate returns”. |

| Chiang and Tsai (2023) | US REIT and stock market | Investor sentiment significantly influences how quickly and efficiently prices adjust, with REITs being more responsive than stocks. Markets react faster during periods of negative sentiment. |

| Hui et al. (2017) | Urban housing in China (Shanghai) | Buyer–seller sentiment has a negative relationship with housing prices, while developer sentiment has a positive relationship. However, this relationship varies over time. |

| Saydometov et al. (2020) | US housing returns | Negative sentiment has a significant impact on housing returns, while positive sentiment has an insignificant relationship. Housing prices only react to increases in negative sentiment, indicating an asymmetric effect. |

| Study | Data/Variables | Sample Period | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muzindutsi et al. (2023) | South African property market; small and medium housing segments; South African Listed Property Index (J253) | June 2004 to December 2020 | GARCH; GJR-GARCH; E-GARCH; Markov-switching VAR models; market-wide investor sentiment index. |

| Lowies et al. (2015) | SA property fund managers | December 2014—17, property fund managers from 27 listed funds on JSE | Non-parametric statistical techniques using Wilcoxon matched paired signed rank test; survey based on using questionnaire. |

| Lin et al. (2008) | US REIT market | Daily return data of REITs: October 1994 to December 2005 | Univariate and multivariate regression models. |

| Kwakye and Chan (2025) | SA housing market | 2005Q1 to 2020Q4 | ARDL; sentiment index (PCA). |

| Lam and Hui (2018) | Hong Kong residential property | 1996 to 2012 | Investor sentiment index (PCA); lag analysis and regression models. |

| Nguyen et al. (2024) | Vietnam real estate corporate bond market | 2010Q1 to 2023Q2; 54 valid quarterly observations | ARDL; Google Trends search data (GVSI). |

| Cheung and Lee (2021) | Commercial real estate returns in Australia | 2008Q1 to 2018Q1 | ARDL. |

| Chiang and Tsai (2023) | US REIT and stock market | 20 May 2010 to 4 October 2019; 2361 observations for each variable | Cointegration model; the Traditional EC model; online search volume (OSV) indices from Google Trends. |

| Hui et al. (2017) | Urban housing in China (Shanghai) | January 2006 to July 2017 | VAR, buyer–seller sentiment, developer sentiment indices using PCA, lag–property return model, and VAR model. |

| Saydometov et al. (2020) | US housing returns | January 2004 to December 2014 | Regression and asymmetry analysis; sentiment index constructed with Google Trends; housing market return model. |

| Investor Sentiment Proxy | Description |

|---|---|

| Share turnover ratio | The share turnover ratio is calculated as the total volume of shares traded divided by the average number of shares listed on the South African stock exchange. This proxy is theoretically grounded in the work of Baker and Stein (2004), who argue that irrational noise traders exist in a high market, and rational investors are unable to fully correct mispricing through arbitrage, often leading to overvalued stock prices. This proxy is also founded in the index of Muguto et al. (2019). |

| Equity issue ratio | The inclusion of the equity issue ratio is validated following its use in the Muguto et al. (2019) index. This proxy is calculated as the proportion of equity issues relative to the total of equity and debt issues in South Africa. Its inclusion is theoretically supported by Baker and Wurgler (2006), who found that periods of high equity issuance are typically followed by low market returns. |

| Advance/decline ratio | The advance/decline ratio measures market breadth by comparing the number of advancing shares to declining shares, adjusted for trading volume (Brown & Cliff, 2004). The advance/decline ratio is included as a proxy in this study’s investor sentiment index, consistent with its use in Muguto et al. (2019). |

| Rand/dollar bid–ask spread | The rand/dollar bid–ask spread is evident in the index used by Muguto et al. (2019) and is defined as the difference between the bid price and the ask price, which reflects the underlying demand for domestic securities. Negative investor sentiment results in the spread widening particularly in response to weak economic conditions and lower capital inflows (Hengelbrock et al., 2013). |

| South African Volatility Index (SAVI) | The South African Volatility Index (SAVI) is included in place of the rand/pound bid–ask spread originally used in Muguto et al. (2019) to address issues of multicollinearity and strengthen the overall reliability of the sentiment index. It will be substituted with SAVI to reduce correlation bias. The SAVI measures the expected market volatility over a 90-day horizon and serves as an indicator of investor fear or uncertainty. |

| CNN Fear and Greed Index | This study replaces the term structure of interest rates used in Muguto et al. (2019) with the CNN Fear and Greed Index to improve the robustness of the sentiment index by capturing the influence of foreign investors, given that South Africa’s financial market is not limited to domestic participants (Liu et al., 2020). Since there is no direct measure for foreign investor sentiment specific to South Africa, this substitution provides a broader perspective. |

| South African Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) | The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) is included in this study’s investor sentiment index to ensure that a greater inclusion of market participants, both high-income and low-income individuals, are captured (Junaeni, 2020). Consumer sentiment signals anticipate household consumption and saving, which in turn influence market participation (OECD, 2022). Although stock prices may not directly shape consumer outlooks, research shows a strong correlation between consumer confidence and overall market sentiment (Rahman & Shamsuddin, 2019). |

| JSE__REITS | JSE_CAP | JSE_LIST | JSE_RIS | FNB | CPI | LT_INT | ST_INT | SENT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 578.1519 | 351.2377 | 443.0977 | 1249.351 | 0.002783 | 4.365546 | 3.486975 | 6.496050 | −1.41 × 10−16 |

| Median | 414.5200 | 286.5800 | 395.9500 | 1184.490 | 0.002778 | 4.400000 | 3.810000 | 7.070000 | −0.069913 |

| Maximum | 1022.900 | 593.8300 | 694.6700 | 1778.560 | 0.007211 | 5.900000 | 5.130000 | 8.670000 | 3.730930 |

| Minimum | 243.5000 | 151.0600 | 206.6600 | 615.8800 | −0.001985 | 2.500000 | 1.560000 | 3.450000 | −2.998668 |

| Std. Dev. | 264.6855 | 140.4554 | 148.9909 | 272.3826 | 0.002008 | 0.809628 | 1.129646 | 1.550190 | 1.671959 |

| Skewness | 0.361474 | 0.368795 | 0.243464 | 0.032641 | 0.010909 | −0.121091 | −0.227659 | −0.730575 | 0.287311 |

| Kurtosis | 1.443557 | 1.557226 | 1.526287 | 2.184661 | 3.022622 | 2.184292 | 1.637599 | 2.295322 | 2.363444 |

| Jarque–Bera | 14.60312 | 13.01877 | 11.94428 | 3.317321 | 0.004898 | 3.589995 | 10.23128 | 13.04801 | 3.646329 |

| Probability | 0.000674 | 0.001489 | 0.002549 | 0.190394 | 0.997554 | 0.166128 | 0.006002 | 0.001468 | 0.161514 |

| Observations | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 | 119 |

| ADF | PP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Level | First Difference | Level | First Difference |

| JSE_REIT | −1.3653 | −9.4440 *** | −1.3616 | −9.3715 *** |

| JSE_CAP | −1.4463 | −9.2194 *** | −1.4471 | −9.1201 *** |

| JSE_LIST | −1.4510 | −9.3823 *** | −1.4677 | −9.2941 *** |

| JSE_RIS | −1.8748 | −8.9969 *** | −1.5001 | −8.8409 *** |

| LT_INT | −1.0352 | −12.0107 *** | −1.0182 | −11.9726 *** |

| ST_INT | −1.5841 | −4.9767 *** | −1.4138 | −8.1267 *** |

| CPI | −1.5139 | −9.5462 *** | −1.6038 | −9.5003 *** |

| FNB | −2.0067 | −5.1958 *** | −3.1837 ** | −4.2804 *** |

| SENT | −2.4644 | −10.1863 *** | −2.4644 | −10.1699 *** |

| Lag | LogL | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1998.969 | NA | 41719.62 | 36.17962 | 36.39931 | 36.26874 |

| 1 | −949.3972 | 1910.031 | 0.001104 | 18.72788 | 20.92479 * | 19.61910 * |

| 2 | −841.8598 | 178.2602 | 0.000703 * | 18.24973 | 22.42387 | 19.94305 |

| 3 | −785.2725 | 84.62598 | 0.001170 | 18.68960 | 24.84096 | 21.18502 |

| 4 | −711.2612 | 98.68177 | 0.001523 | 18.81552 | 26.94411 | 22.11305 |

| 5 | −618.5356 | 108.5975 | 0.001566 | 18.60425 | 28.71006 | 22.70388 |

| 6 | −514.0976 | 105.3789 | 0.001506 | 18.18194 | 30.26498 | 23.08367 |

| 7 | −389.8162 | 105.2473 * | 0.001249 | 17.40209 | 31.46236 | 23.10593 |

| 8 | −258.3189 | 90.03420 | 0.001243 | 16.49223 * | 32.52972 | 22.99817 |

| Hypothesized No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Trace Statistic | 0.05 Critical Value | Prob. Critical Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0.447093 | 270.7052 | 197.3709 | 0.0000 |

| At most 1 | 0.379547 | 201.3752 | 159.5297 | 0.0000 |

| At most 2 | 0.327129 | 145.5304 | 125.6154 | 0.0017 |

| At most 3 | 0.269556 | 99.17479 | 95.75366 | 0.0285 |

| At most 4 | 0.182360 | 62.42482 | 69.81889 | 0.1686 |

| At most 5 | 0.163695 | 38.86886 | 47.85613 | 0.2655 |

| At most 6 | 0.074618 | 17.95369 | 29.79707 | 0.5695 |

| At most 7 | 0.046149 | 8.880477 | 15.49471 | 0.3765 |

| At most 8 | 0.028247 | 3.352532 | 3.841465 | 0.0671 |

| Panel A | ||||||

| Lag | LRE stat | df | Prob. | Rao F-stat | df | Prob. |

| 1 | 106.7593 | 81 | 0.0292 | 1.346502 | (81, 584.1) | 0.0299 |

| Panel B | ||||||

| Lag | LRE stat | df | Prob. | Rao F-stat | df | Prob. |

| 1 | 106.7593 | 81 | 0.0292 | 1.346502 | (81, 584.1) | 0.0299 |

| Panel A | |||||

| Lag | LRE stat | df | Prob. | Rao F-stat | Prob. |

| 1 | 68.14886 | 81 | 0.8451 | 0.827924 | 0.8489 |

| 2 | 83.67564 | 81 | 0.3973 | 1.035636 | 0.4047 |

| 3 | 80.02616 | 81 | 0.5097 | 0.986138 | 0.5171 |

| 4 | 70.70446 | 81 | 0.7861 | 0.861598 | 0.7909 |

| Panel B | |||||

| Lag | LRE stat | df | Prob. | Rao F-stat | Prob. |

| 1 | 68.14886 | 81 | 0.8451 | 0.827924 | 0.8489 |

| 2 | 160.9437 | 162 | 0.5087 | 0.984572 | 0.5395 |

| 3 | 236.1872 | 243 | 0.6109 | 0.942051 | 0.6922 |

| 4 | 337.1884 | 324 | 0.2955 | 0.998895 | 0.5044 |

| Long Run | Short Run | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cointegrating Eq: | Error Correction1 | Lag Variables | D(JSE-REITS) | D(JSE_CAP) | D(JSE_LIST) | D(JSE_RIS) | D(FNB) | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) |

| JSE__REITS (−1) | 1 | COINTEQ1 | −0.1344 | 0.103415 | 0.184969 | 1.624092 | 3.55 × 10−5 | 0.026355 |

| [−0.26724] | [0.33280] | [0.43465] | [1.25452] | [3.98126] *** | [2.93470] *** | |||

| JSE_CAP (−1) | −1.619034 *** | D(LT_INT (−1)) | −53.9032 | −32.9045 | −44.5103 | −123.669 | −0.0012 | −1.09151 |

| −0.13036 | [−1.81467] | [−1.79281] | [−1.77087] | [−1.61736] | [−2.28656] | [−2.05786] | ||

| [−12.4196] | ||||||||

| JSE_LIST (−1) | −0.394628 *** | D(LT_INT (−2)) | 0.28717 | 1.598303 | 1.3802 | 6.882041 | −0.00044 | −0.30657 |

| −0.10561 | [0.01032] | [0.09297] | [0.05862] | [0.09609] | [−0.88415] | [−0.61706] | ||

| [−3.73669] | ||||||||

| JSE_RIS (−1) | 0.125708 *** | D(LT_INT (−3)) | −12.5102 | −5.93372 | −7.34415 | 37.31535 | 0.001327 | 0.220460 |

| −0.01107 | [−0.52106] | [−0.39999] | [−0.36150] | [0.60378] | [3.11913] | [0.51424] | ||

| [11.3560] | ||||||||

| LT_INT (−1) | 1.191475 | D(LT_INT (−4)) | −23.7586 | −13.1713 | −10.4812 | 1.569130 | 0.000562 | 0.279700 |

| −7.27467 | [−0.99914] | [−0.89646] | [−0.52091] | [0.02563] | [1.33250] | [0.65872] | ||

| [0.16378] | ||||||||

| ST_INT (−1) | −5.141133 ** | D(ST_INT (−1)) | 29.49224 | 19.02866 | 26.99705 | 69.79726 | 3.97 × 10−5 | −0.16037 |

| −2.21397 | [2.05838] | [2.14942] | [2.22678] | [1.89243] | [0.15649] | [−0.62681] | ||

| [−2.32213] | ||||||||

| CPI (−1) | 0.256126 | D(ST_INT (−2)) | 16.33598 | 9.891134 | 11.43038 | 16.10445 | −0.00016 | −0.06045 |

| −3.61405 | [1.07779] | [1.05617] | [0.89124] | [0.41276] | [−0.59409] | [−0.22336] | ||

| [0.07087] | ||||||||

| FNB (−1) | −6114.802 *** | D(ST_INT (−3)) | −8.63212 | −9.51917 | −9.13444 | −72.7966 | −0.00022 | 0.760485 |

| −1311.13 | [−0.61275] | [−1.09360] | [−0.76629] | [−2.00743] | [−0.89047] | [3.02316] | ||

| [−4.66376] | ||||||||

| SENTIMENT_INDEX (−1) | −3.112869 * | D(ST_INT (−4)) | 12.7373 | 9.256711 | 10.03907 | 56.78004 | 0.000204 | 0.144986 |

| −1.68165 | [0.80842] | [0.95085] | [0.75300] | [1.39997] | [0.73123] | [0.51534] | ||

| [−1.85108] | ||||||||

| C | 54.00981 | D(CPI (−1)) | 2.728128 | −1.52706 | −2.13032 | −39.839 | −0.00047 | 0.422787 |

| [0.15793] | [−0.14307] | [−0.14574] | [−0.89593] | [−1.52040] | [1.37066] | |||

| N/A | D(CPI (−2)) | 10.12246 | 7.060918 | 10.66681 | 27.30531 | −0.00044 | −0.13558 | |

| [0.58119] | [0.65613] | [0.72379] | [0.60904] | [−1.43398] | [−0.43595] | |||

| D(CPI (−3)) | 2.215684 | 1.177128 | −4.97644 | 2.904573 | −0.00021 | 0.07739 | ||

| [0.12313] | [0.10587] | [−0.32682] | [0.06270] | [−0.67168] | [0.24085] | |||

| D(CPI (−4)) | 2.058617 | 1.594325 | 1.717197 | 16.95361 | −0.0002 | −0.0808 | ||

| [0.11542] | [0.14467] | [0.11378] | [0.36926] | [−0.64349] | [−0.25370] | |||

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX (−1)) | −11.2226 | −6.58447 | −8.61914 | −17.934 | 7.86 × 10−5 | −0.17367 | ||

| [−1.84511] * | [−1.75205] | [−1.67469] | [−1.14543] | [0.72929] | [−1.59906] | |||

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX (−2)) | −4.37861 | −2.10718 | −2.08198 | −1.13566 | 7.12 × 10−5 | −0.2916 | ||

| [−0.80965] | [−0.63060] | [−0.45497] | [−0.08158] | [0.74291] | [−3.01964] | |||

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX (−3)) | −7.40937 | −3.75964 | −5.21493 | −2.98674 | −0.00012 | −0.10739 | ||

| [−1.41537] | [−1.16233] | [−1.17728] | [−0.22164] | [−1.32485] | [−1.14879] | |||

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX (−4)) | −5.16415 | −4.16281 | −4.61794 | −27.4321 | −0.00011 | −0.11369 | ||

| [−1.08866] | [−1.42029] | [−1.15050] | [−2.24655] ** | [−1.26561] | [−1.34225] | |||

| C | −5.52853 | −2.60421 | −2.98046 | 1.866193 | −7.62 × 10−5 | −0.05782 | ||

| [−1.48953] | [−1.13556] | [−0.94900] | [0.19533] | [−1.15879] | [−0.87237] | |||

| Dependent Variable: D(JSE__REITS) | Dependent Variable: D(JSE_RIS) | Dependent Variable: D(CPI) | |||||||||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D(JSE_CAP) | 5.330853 | 4 | 0.2550 | D(JSE__REITS) | 9.935989 | 4 | 0.0415 | D(JSE__REITS) | 3.201173 | 4 | 0.5247 |

| D(JSE_LIST) | 4.886736 | 4 | 0.2991 | D(JSE_CAP) | 7.828067 | 4 | 0.0981 | D(JSE_CAP) | 3.337311 | 4 | 0.5030 |

| D(JSE_RIS) | 4.683666 | 4 | 0.3213 | D(JSE_LIST) | 9.006663 | 4 | 0.0609 | D(JSE_LIST) | 1.617825 | 4 | 0.8056 |

| D(LT_INT) | 5.062631 | 4 | 0.2809 | D(LT_INT) | 3.383717 | 4 | 0.4958 | D(JSE_RIS) | 4.138259 | 4 | 0.3876 |

| D(ST_INT) | 7.272555 | 4 | 0.1222 | D(ST_INT) | 8.420291 | 4 | 0.0773 | D(LT_INT) | 1.857324 | 4 | 0.7620 |

| D(CPI) | 0.423288 | 4 | 0.9805 | D(CPI) | 1.274389 | 4 | 0.8657 | D(ST_INT) | 1.245912 | 4 | 0.8705 |

| D(FNB) | 16.46857 | 4 | 0.0025 | D(FNB) | 5.082213 | 4 | 0.2790 | D(FNB) | 4.540129 | 4 | 0.3378 |

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 5.356358 | 4 | 0.2526 | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 6.420827 | 4 | 0.1698 | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 12.16341 | 4 | 0.0162 |

| All | 42.72253 | 32 | 0.0975 | All | 40.77941 | 32 | 0.1374 | All | 32.59411 | 32 | 0.4376 |

| Dependent Variable: D(JSE_CAP) | Dependent Variable: D(LT_INT) | Dependent Variable: D(FNB) | |||||||||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D(JSE__REITS) | 9.893911 | 4 | 0.0423 | D(JSE__REITS) | 8.412893 | 4 | 0.0776 | D(JSE__REITS) | 8.157663 | 4 | 0.0860 |

| D(JSE_LIST) | 7.020539 | 4 | 0.1348 | D(JSE_CAP) | 7.311118 | 4 | 0.1203 | D(JSE_CAP) | 6.223693 | 4 | 0.1831 |

| D(JSE_RIS) | 5.792173 | 4 | 0.2152 | D(JSE_LIST) | 0.389968 | 4 | 0.9833 | D(JSE_LIST) | 4.802774 | 4 | 0.3081 |

| D(LT_INT) | 4.778757 | 4 | 0.3108 | D(JSE_RIS) | 7.383485 | 4 | 0.1170 | D(JSE_RIS) | 9.092793 | 4 | 0.0588 |

| D(ST_INT) | 8.080858 | 4 | 0.0887 | D(ST_INT) | 16.60522 | 4 | 0.0023 | D(LT_INT) | 16.72743 | 4 | 0.0022 |

| D(CPI) | 0.489825 | 4 | 0.9745 | D(CPI) | 8.589159 | 4 | 0.0722 | D(ST_INT) | 1.566132 | 4 | 0.8149 |

| D(FNB) | 14.97126 | 4 | 0.0048 | D(FNB) | 5.642348 | 4 | 0.2275 | D(CPI) | 5.379850 | 4 | 0.2505 |

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 5.347930 | 4 | 0.2534 | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 4.217754 | 4 | 0.3773 | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 5.855993 | 4 | 0.2102 |

| All | 44.17516 | 32 | 0.0744 | All | 100.0395 | 32 | 0.0000 | All | 55.91556 | 32 | 0.0055 |

| Dependent Variable: D(JSE_LIST) | Dependent Variable: D(ST_INT) | Dependent Variable: D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | |||||||||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D(JSE__REITS) | 7.214975 | 4 | 0.1250 | D(JSE__REITS) | 5.186450 | 4 | 0.2687 | D(JSE__REITS) | 26.41612 | 4 | 0.0000 |

| D(JSE_CAP) | 5.657410 | 4 | 0.2262 | D(JSE_CAP) | 4.473701 | 4 | 0.3457 | D(JSE_CAP) | 24.26611 | 4 | 0.0001 |

| D(JSE_RIS) | 4.060354 | 4 | 0.3979 | D(JSE_LIST) | 7.032553 | 4 | 0.1342 | D(JSE_LIST) | 2.954693 | 4 | 0.5654 |

| D(LT_INT) | 3.959819 | 4 | 0.4115 | D(JSE_RIS) | 2.335543 | 4 | 0.6743 | D(JSE_RIS) | 13.68022 | 4 | 0.0084 |

| D(ST_INT) | 7.324842 | 4 | 0.1197 | D(LT_INT) | 2.551096 | 4 | 0.6355 | D(LT_INT) | 4.831366 | 4 | 0.3050 |

| D(CPI) | 0.579263 | 4 | 0.9653 | D(CPI) | 14.28532 | 4 | 0.0064 | D(ST_INT) | 9.813604 | 4 | 0.0437 |

| D(FNB) | 10.31104 | 4 | 0.0355 | D(FNB) | 5.417015 | 4 | 0.2471 | D(CPI) | 2.013280 | 4 | 0.7333 |

| D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 4.454965 | 4 | 0.3479 | D(SENTIMENT_INDEX) | 0.282031 | 4 | 0.9909 | D(FNB) | 19.73680 | 4 | 0.0006 |

| All | 32.09852 | 32 | 0.4619 | All | 49.19381 | 32 | 0.0266 | All | 89.35362 | 32 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nel, C.; Moodley, F.; Ferreira-Schenk, S. The Influence of Investor Sentiment on the South African Property Market: A Comparative Assessment of JSE Indices. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040231

Nel C, Moodley F, Ferreira-Schenk S. The Influence of Investor Sentiment on the South African Property Market: A Comparative Assessment of JSE Indices. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(4):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040231

Chicago/Turabian StyleNel, Charlize, Fabian Moodley, and Sune Ferreira-Schenk. 2025. "The Influence of Investor Sentiment on the South African Property Market: A Comparative Assessment of JSE Indices" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 4: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040231

APA StyleNel, C., Moodley, F., & Ferreira-Schenk, S. (2025). The Influence of Investor Sentiment on the South African Property Market: A Comparative Assessment of JSE Indices. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(4), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040231