1. Introduction

The report from the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China indicates that development has entered a phase marked by simultaneous strategic opportunities and challenges, compounded by rising uncertainties and unpredictable elements. Recurring events, such as Federal Reserve rate hikes and international conflicts, have established a VUCA environment (volatile, unpredictable, complex, ambiguous) for businesses, suggesting that these characteristics may become the new norm (

Shan et al., 2021). At this point, equity incentives function not only as a mechanism to reduce agency costs but also as a method to identify and enhance core talents’ propensity for risk-taking in highly uncertain circumstances. This makes it possible for businesses to continuously resist, recover, and restructure in the face of shocks, which is what is meant by organizational resilience (

Duchek, 2020). Nevertheless, current research has not examined whether and under what circumstances equity incentives can bolster organizational resilience by encouraging core employees’ propensity for risk-taking and resource integration behaviors.

This study focuses on Chinese A-share listed firms to explore the relationship between organizational resilience and executive equity incentives with a framework centered on agency costs and managerial shortsightedness as a mediator and internal control as moderators. Specifically, it examines (1) a significant inverted U-shaped relationship between executive equity incentives and corporate organizational resilience; (2) the mediating role of internal control in this relationship; (3) whether executive equity incentives primarily affect organizational resilience by influencing agency costs and short-term management behavior; and (4) the heterogeneity in private enterprises and those enterprises with high financing constraints, high information asymmetry and strong economic policy uncertainty.

The contributions lie in (1) confirming the inverted U-shaped relationship between executive equity incentives and corporate organizational resilience; (2) revealing that high-quality internal controls can mitigate the curvature of this inverted U-shaped relationship and shift the turning point forward; and (3) offering significant empirical evidence and policy insights for private firms and those enterprises with high financing constraints, high information asymmetry and strong economic policy uncertainty.

2. Literature Review

Early research on organizational resilience in organizations predominantly concentrated on conceptual exploration, seeking to clarify fundamental components and boundaries. The term “resilience” originated in physics, describing the ability of a material to recover to its original state following deformation due to external forces. This notion was then integrated into management studies (

Meyer, 1982), distinctly characterized as an organization’s ability to respond rapidly, recover, and exceed its prior condition during crises (

Buyl et al., 2019), with suggested approaches encompassing absorptive resilience and adaptive resilience (

Conz & Magnani, 2020). Additionally, various factors affect the resilience of corporate organizations. Firstly, the strategic dimension of resilience is formed internally by managerial decision agility. Initiatives for digital transformation, such as digital tools, increase process responsiveness and flexibility, which strengthens organizational resilience (

Miceli et al., 2021;

Garrido et al., 2024). Resilient leaders exhibit strong leadership skills, which enable them to rapidly reinstate regular operations within pressured teams while inspiring employees to collaborate and propel organizational progress (

C. Chen et al., 2023). An active and flexible corporate culture enhances employee bonding, thereby strengthening organizational resilience (

Li et al., 2022). The psychological capital of employees, including self-efficacy and optimistic dispositions, bolsters an organization’s resilience under challenging circumstances and promotes ongoing organizational growth (

Linnenluecke, 2017). Early studies indicate that digital maturity and digital technologies may improve supply chain digitalization, consequently fortifying business supply chain resilience (

Zouari et al., 2020). In relation to external circumstances, collaborative innovation among enterprises significantly enhances organizational resilience, particularly under high economic policy uncertainty, underscoring the importance of this cooperative approach (

Huang et al., 2024). In addition to increasing an organization’s transparency and governance effectiveness, a strong investor protection mechanism also increases investment, broadens financing options, lessens information asymmetry, and successfully deters potentially corrupt behavior, all of which help businesses recover from crises (

Hu et al., 2020). As a significant external resource, the director relationship network is crucial for helping businesses withstand external shocks by offering the resources and support they need (

Ren et al., 2023).

Executive equity incentives serve as a long-term strategy that aligns management interests with corporate sustainability, thereby pushing executives toward continuous value generation. Recent research investigations into the economic effects have predominantly concentrated on two contrasting viewpoints: the “incentive effect” and the “self-interest effect.” (

Lu et al., 2009;

Y. Wu & Wu, 2010). Some experts argue that CEO equity incentive schemes produce favorable economic results for businesses. Based on optimum contract theory, such systems align the interests of executives with those of shareholders, thereby minimizing agency costs. This motivates executives to concentrate on the company’s long-term growth (

Mao & Li, 2016), Additionally, these incentives attract and retain high-quality talent, thereby facilitating the fulfillment of social responsibilities (

Zong et al., 2013). However, other scholars have also proposed different perspectives. Entrenchment effect theory posits that certain data reveals equity incentives may enhance executives’ power and informational advantages (

Z. Zhang & Xiao, 2012), thereby fostering opportunistic behaviors such as earnings management (

Li, 2016). Specific expressions include abusing options via discounted exercise prices or too lenient performance criteria; prioritizing short-term profits at the expense of strategic planning, potentially resulting in inefficient investments (

X. Chen et al., 2016); and lowering the capacity of accounting conservatism to mitigate overinvestment (

G. Wang & Peng, 2019). Further research suggests that stock incentives may allow CEOs to manipulate earnings data, mislead investors on real performance, and consequently raise equity capital costs (

Zhou & Lei, 2014). Additional studies indicate that equity incentives enable CEOs to become involved in opportunistic behavior, reduce corporate commitment to environmental governance (

C. Wu & Guo, 2025), and may exacerbate the increasing trend of cost elasticity resulting from demand uncertainty (

Wei et al., 2021).

Although executive equity incentives and organizational resilience have received considerable attention in their respective fields, research on their relationships is relatively scarce. The aforementioned literature indicates that current research mostly examines the influence of executive equity incentives on corporate performance. Nonetheless, a substantial study gap remains concerning organisational resilience, a factor crucial to the enduring sustainable development of firms. Consequently, in light of the more intricate and unstable global economic landscape, it is essential to investigate the potential impact of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience. What are the mechanisms underlying this effect? Do the varying enterprise features have disparate effects?

To address these issues, this study explores the impact of executive equity incentives on corporate organizational resilience from a theoretical perspective grounded in the convergence of interest theory and entrenchment effect. This study empirically examined the relationship between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience, mediating mechanisms, and heterogeneous effects using data from Chinese A-share listed companies between 2009 and 2023. Furthermore, this research aims to provide a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for enterprises to formulate more scientific and reasonable incentive policies while also enriching empirical evidence on corporate organizational resilience. This finding offers theoretical support and practical insights for regulatory authorities to constrain and supervise the implementation of equity incentives in listed companies.

3. Theoretical Derivation and Research Hypothesis

3.1. The “Double-Edged Sword” Effect of Executive Equity Incentive on the Resilience of Enterprise Organization

3.1.1. Moderate Executive Equity Incentives to Enhance Organizational Resilience

In the early stages of implementing equity incentives, the interests of executives and shareholders eventually converge as the incentive strength increases. Executives are encouraged to take proactive risks and actively support the long-term growth of the organization as a result of this alignment. The concept of converging interests posits that when CEOs possess company shares, their personal wealth becomes more dependent on the enterprise’s market value. This alters their decision-making from immediate self-interest to optimizing the company’s overall interests (

Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

The Self-Determination Theory posits that matching external incentives with internal motivation significantly improves autonomy in executive motivation. Within the moderate equity incentive range, executives’ share allocations correspond with their self-interests, promoting alignment with shareholder interests without compromising intrinsic drive. By tightly linking executives’ personal wealth to corporate long-term value growth, this equity incentive mechanism shifts decision-making from the short-term self-interest to maximizing collective corporate benefits (

Zhao et al., 2020). This convergence of interests alleviates principal-agent conflicts between shareholders and executives, significantly improving corporate strategic stability and adaptability in uncertain environments (

N. Xu et al., 2022).

Second, senior management theory and dynamic capacity theory work together to clarify the underlying factors that contribute to an organization’s long-term competitive advantage at the executive behavior level: As the main bearer of organizational dynamic capabilities, the senior management team’s strategic choices and actions have a direct impact on the enterprise’s capacity to recognize changes in the environment, take advantage of market opportunities, and realign resource foundations in order to adjust to quickly changing environments. According to this theory, executives’ motivation as “organizational agents” is greatly increased by moderate equity incentives since they strongly link personal wealth with long-term company value. The executive team’s proactive perception of market signals and technological trends, the shift in decision-making focus from risk avoidance to strategic risk-taking, the shift from short-term financial performance to steadfast investment in long-term innovation capabilities (

K. Yang et al., 2019;

W. Wu et al., 2024), and the increased bravery to restructure organizational models and business processes when needed are all examples of this enhanced behavioral agency. Equity incentives, when applied within suitable constraints, serve as a crucial institutional mechanism to encourage strategic actions instead of promoting short-term opportunism (

Armstrong et al., 2010). By methodically converting leaders’ improved behavioral agency into organizational dynamic skills, organizations can cultivate resilience to confront problems and facilitate recovery.

In summary, modest equity incentives improve executive motivation, enhance their behavioral initiative, steadily develop the enterprise’s dynamic capabilities, and ultimately bolster organizational resilience.

3.1.2. Excessive Executive Equity Incentives Weaken Organizational Resilience

Excessive equity incentives becoming a “trap inducing opportunism” instead of a “motivation-compatible” instrument is the main reason why they undermine organizational resilience. Such incentives eventually undermine business resilience by influencing executives’ goals and encouraging shortsighted practices. Initially, at the level of motivational distortion, excessive incentives induce the “entrenchment effect” and generate “agent-principal conflicts,” switching executives’ attention from value creation to profit maximization (

J. Xu et al., 2016). Excessive incentive intensity, as posited by managerial power theory, may lead CEOs to exploit their influence to strengthen their positions, transforming equity incentives from motivational instruments into mechanisms of entrenchment for personal benefit. Attaining significant gains from stocks and options may skew their risk tolerance. Executives’ goals transition from fostering the rapid expansion of the real economy to guaranteeing and optimizing the secure actualization of this substantial floating wealth.

Additionally, executives’ self-interested incentives at the level of short-sighted behavior immediately result in a sequence of opportunistic and short-term activities that compromise long-term resilience (

J. Xu et al., 2016). Executives’ rational choices change from long-term value creation to looking for “shortcuts” that can quickly raise stock prices and satisfy exercise requirements when meeting incentives takes priority. Executives may, on the one hand, manipulate earnings, reduce capital expenditures for maintenance, and squeeze suppliers to inflate short-term performance (

Li, 2016). On book value, these activities generate income, but in reality, they show that governance systems are poor. The efficacy of corporate governance is further undermined when executives have too much power because they may strengthen their positions by limiting board independence and creating closed governance frameworks. The core of organizational resilience has been weakened and business innovation performance and value generation capabilities are significantly eroded (

J. Xu et al., 2016;

Sun & Yang, 2019).

Conversely, it is characterized by a systematic evasion of innovation and transformation. Owing to long research and development cycles and elevated failure risks, CEOs facing substantial incentives sometimes reduce core innovation investments, opting instead for rapid-return marginal improvements or market speculation to sustain current technical trajectories and stock valuations. This approach undermines the company’s persistent advantages in dynamic market situations (

Tang et al., 2022), limiting opportunities to transform crises into safety when confronted with hazards.

In conclusion, when executive equity incentives surpass a specific threshold, they may lead to myopic behaviors, governance failures, and a decline in trust among executives, consequently undermining the organization’s adaptability and resilience in complex and volatile environments. The beneficial effects of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience ultimately turn detrimental.

Consequently, this study posits the following research hypothesis:

H1. The intensity of executive equity incentive affects the organizational resilience of enterprises, showing an inverted “U”-shaped nonlinear relationship.

3.2. The Regulatory Role of Internal Control

An essential part of corporate governance, internal control has two regulatory roles in the inverted U relationship between organizational resilience and executive equity incentives. Depending on how strong the equity incentives are, it has different regulatory impacts. In the low incentive range, this enhances the operational efficiency of the incentive mechanism. In the high-incentive range, it serves to control risks and correct behaviors.

In the low-motivation spectrum, efficient internal controls can enhance the efficacy of incentives by optimizing resource integration and allocation mechanisms inside the resource-based perspective. This concept posits that a company’s sustained competitive advantage arises from its capacity to acquire, integrate, and leverage rare, non-replicable resources. At minimal incentive levels, equity incentives may be limited by CEOs’ opportunistic behaviors, inadequately promoting innovation efforts. In these situations, high-quality internal controls can optimize resource integration (

X. Yang et al., 2012), improve information transparency, and refine performance evaluation systems, ultimately facilitating efficient resource allocation (

He & Huang, 2021). The alignment between CEO actions and firm strategic objectives expedites the attainment of incentive benefits.

Internal controls specifically provide regulatory effects in low incentive levels via three pathways: starting by instituting information transparency techniques to diminish knowledge asymmetry, allowing executives to precisely comprehend corporate strategic objectives and value development avenues. next by employing resource coordination methods to enhance allocation and facilitate CEOs’ strategic innovation and risk-taking behaviors. Ultimately, through performance evaluation systems that clarify incentive criteria and assessment frameworks, executives’ emphasis on long-term value generation is improved. These mechanisms collectively facilitate equity incentives to more efficiently propel corporate innovation strategies earlier (

D. Chen & Xing, 2020), permitting organizational resilience to achieve optimal enhancement effects even at comparatively low incentive levels, evidenced by a forward-shifted inflection point in the inverted “U” curve.

Conversely, in high incentive ranges, effective internal controls may mitigate the detrimental impacts of excessive incentives via the supervisory and balancing mechanisms inherent in principal-agent theory. The theory posits that the difference in aims between shareholders and managers is the fundamental source of agency difficulties, wherein executives may misuse control rights for personal benefit, undermining long-term organizational value. Excessively large equity incentives may compel executives to engage in earnings management or asset manipulation to artificially improve performance growth (

Li, 2016) or to employ myopic strategies such as reducing R&D investments and preserving current business models to optimize short-term profits, consequently undermining organizational resilience (

Sun & Yang, 2019).

At this situation, effective internal controls can directly mitigate agency costs by enhancing supervisory checks and balances, substantially diminishing executives’ discretionary authority and effectively restraining their potential short-term self-serving behaviors motivated by excessive incentives (

He & Huang, 2021). Internal controls specifically produce regulatory effects in high-incentive circumstances via three pathways: first of all, audit supervision mechanisms curtail executives’ earnings management and asset manipulation to guarantee accuracy of financial reports (

Doyle et al., 2007); subsequently, budget control and resource allocation mechanisms discourage executives from excessively focusing resources on short-term performance enhancements to the benefit of long-term value creation; ultimately, power checks and balances mechanisms restrict the augmentation of executives’ control rights to avert the emergence of the “entrenchment effect”.

In conclusion, internal control significantly moderates the link between equity incentives and organizational resilience, which accelerates the distribution of incentive advantages in low-motivation contexts, increasing organizational resilience. Conversely, it alleviates adverse incentive effects in high-motivation contexts, preserving organizational resilience. This dual moderating mechanism mitigates the inverted “U” shaped relationship between equity incentives and corporate organizational resilience, hence diminishing hazards linked to excessive incentives.

Based on this, this paper puts forward Hypothesis H2:

H2. Internal control can accelerate the release of incentive utility so that the executive equity incentive can achieve the highest value in promoting organizational resilience at a lower incentive intensity, and can restrain the negative inhibitory effect of excessive equity incentives on organizational resilience.

4. Research Design

4.1. Samples and Data

This study selected data from Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed companies from 2009 to 2023 as the research sample, and the sample data were processed as follows: (1) samples from the finance and insurance industries were excluded; (2) samples with *ST, ST, etc., were excluded; (3) samples with missing key variables were also removed; and (4) all variables were winsorized by 1% above and below the mean to reduce the impact of extreme values. A total of 34,273 samples were obtained. The financial data in this study were sourced from the CSMAR database and the internal control index was derived from the DIB database.

4.2. Variable Definition

4.2.1. The Dependent Variable Was Enterprise Organizational Resilience

Enterprise organizational resilience refers to an enterprise’s ability to adapt and recover when facing changes in the external environment and internal challenges. To measure organizational resilience, this study draws on the research of

X. Wu and Feng (

2022), constructing a comprehensive evaluation index from two core dimensions: volatility and growth. Volatility is measured by the standard deviation of monthly stock returns for a year, reflecting a company’s stability in handling market fluctuations. Growth is assessed by the cumulative increase in sales revenue over three years, indicating a company’s long-term development potential. Utilizing this basis, this study applies the entropy weight method to impartially assign weights to these two aspects, so creating a comprehensive organizational resilience index (

Res). This measurement method aligns with the theoretical implications of organizational resilience as “resilience” and “growth,” while also circumventing subjective weighting biases, thereby offering a more comprehensive and objective insight into enterprises’ ongoing adaptability and competitive evolution in dynamic environments.

4.2.2. Explain the Variable of Executive Equity Incentives

This study draws on the research of

Bergstresser and Philippon (

2006), and

D. Chen and Zhang (

2023), using executive equity incentives (

Incentive) as an explanatory variable. This statistic, defined as the ratio of stock price appreciation to total remuneration for a 1% increase in shares, is computed using Formula (1). The selection of this indicator is predicated on two principal factors: Initially, it logically corresponds with the convergence-of-interest hypothesis and optimal contract theory, offering direct assessment of the relationship between executive wealth and shareholder wealth. This facilitates the measurement of the sensitivity of compensation to performance and the robustness of equity incentive alignment. Secondly, by combining two principal equity incentive mechanisms, it effectively illustrates the real effects of stock price variations on CEO wealth. This approach exhibits more sensitivity, cross-context comparability, and a more accurate representation of long-term binding effects in incentive contracts than typical static indicators such as dummy variables or shareholding ratios.

- (1)

Variable adjustment, Internal control

The quality of internal control indicates the overall effectiveness of an enterprise’s internal control system regarding design rationality, implementation efficacy, and risk management capabilities. This study employs the methodology of

H. Yu and Wu (

2015) to quantify this variable, utilizing the internal control index published by the DIB (Internal Control and Risk Management Database) and applying its natural logarithm as a proxy variable (IC). This index, derived from the COSO framework and China’s “Basic Standards for Enterprise Internal Control,” establishes a multi-tiered indicator system encompassing five components: internal environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and internal supervision, which utilizes a composite weighting approach to ascertain the weights of each dimension, thus methodically assessing the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the enterprise’s internal control system. The natural logarithm form of this index facilitates dimensionality reduction and mitigates heteroskedasticity concerns. A higher IC value signifies superior internal control quality, demonstrating enhanced capabilities in risk mitigation, compliance operations, and the reliability of information disclosure.

- (2)

Control variables

This study considers numerous factors that may affect research outcomes in the model formulation. Based on the existing literature, the chosen control variables are classified into three primary categories: corporation financial characteristics, corporate governance elements, and external environmental factors. Corporate characteristic variables encompass firm size (Size), debt-to-asset ratio (Lev), cash flow ratio (Cashflow), revenue growth rate (Growth), return on total assets (Roa), fixed asset ratio (Fixed), and firm age (FirmAge) to account for potential effects of firm heterogeneity on resource allocation, financial structure, stage of growth, and profitability. Corporate governance variables encompass the institutional investor shareholding ratio (Inst), board size (Board), and dual role (Dual) to reflect for the influence of governance structure and variations in managerial power on the efficacy of incentives and decision-making behavior. External environmental variables include fiscal support (FinSu) and advanced industrial structure (IndAd) to account for institutional and environmental elements, such as levels of government intervention and stages of regional industrial growth. The model also includes fixed effects for individual and years to account for time-invariant firm heterogeneity and consistent annual macroeconomic shocks across firms.

The specific definitions and measurement methods of the main variables in this study are listed in

Table 1.

4.3. Model Design

To test the impact of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience, this study constructed the following research Model (2):

To test the moderating effect of internal control quality on the impact of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience, this study constructed research Model (3):

where

i stands for the enterprise,

t stands for the year, and

μj represents the fixed effect of the individual, which is used to control the heterogeneity among different enterprises and ensure that the model estimation is not affected by the specific characteristics of the enterprise.

γt,

is the fixed effect of year, which is used to control the impact of macroeconomic factors on enterprise organizational resilience.

α0 and

β0 are the constant terms;

α1 and

α2 in Model (2);

β1–

β4 in Model (3) represent the regression coefficients for the main explanatory variables;

α3–

α14 in Model (2) and

β5–

β16 in Model (3) are the coefficients of the control variables.

εi,t is the residual term. In additional, this paper has modified the standard errors of all regressions to account for clustering at the business level.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the main variables in Model (2). The findings reveal that the explanatory variable of organizational resilience (

Res) has a minimum value of 0.021, a maximum value of 0.925, and a mean of 0.487, indicating considerable diversity in organizational resilience among the sampled firms. The mean value for the independent variable, executive equity incentives (

Incentive), was 0.178, indicating an average intensity of roughly 17.8% for executive equity incentives within the sample. The statistical characteristics of additional variables generally correspond with current research and are not discussed further here.

5.2. Regression Results

5.2.1. Test of Main Effects

This study utilized a fixed-effects model to perform regression analysis on Model (2) in order to test hypothesis H1, with the findings displayed in

Table 3. Columns (1) to (4) present the varying regression results for executive equity incentives and organizational resilience under Model (2) without control variables or fixed effects, with only control variables, with only fixed effects, and with both control variables and fixed effects included. The regression analysis reveals that the coefficients for the explanatory variable

Incentive are 0.319, 0.367, 0.008, and 0.007, with significance levels of 1%, 1%, 5%, and 5%, respectively. The regression coefficients for the explanatory variable

Incentive2 are −0.232, −0.256, −0.017, and −0.016, all statistically significant at the 1% level. The findings reveal a notable inverted U-shaped correlation between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience. When the intensity of executive equity incentives diminishes below a particular level, they produce a “promoting effect” on organizational resilience. However, when above this threshold, they generate “The Entrenchment Effect”. Hypothesis H1 is therefore validated.

5.2.2. Moderating Effect Tests

This study performed regression analysis on Model (3) to evaluate Hypothesis H2, with the findings displayed in column (5) of

Table 3. The regression results reveal that the coefficients (

β1,

β2) for the explanatory variables

Incentive and

Incentive2 are 0.052 and −0.054, respectively. The coefficients (

β3,

β4) for the interaction terms

Incentive ×

IC and

Incentive2 ×

IC are −0.081 and 0.072, respectively, both significant at the 1% and 5% levels. These results in Model (2) illustrate an inverted U-shaped correlation between

Incentive and

Res, while Model (3) indicates that

β1 ×

β4 −

β2 ×

β3 is significantly negative, suggesting that as the quality of internal control increases, the peak of the curve connecting executive equity incentives to organizational resilience shifts downward. This link indicates that the quality of internal control improves the effectiveness of executive equity incentives, allowing organizational resilience to attain its maximum potential even with relatively modest amounts of such incentives. Moreover, as a

2 is markedly less than zero and

β4 is much greater than zero, which suggests that as the effectiveness of internal controls improves, the inverted U-shaped relationship curve between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience becomes less pronounced. The results indicate that improved internal control quality strengthens the positive benefits of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience while reducing their adverse consequences. In alignment with the prior analysis, Hypothesis H2 is corroborated.

5.3. Robustness Test

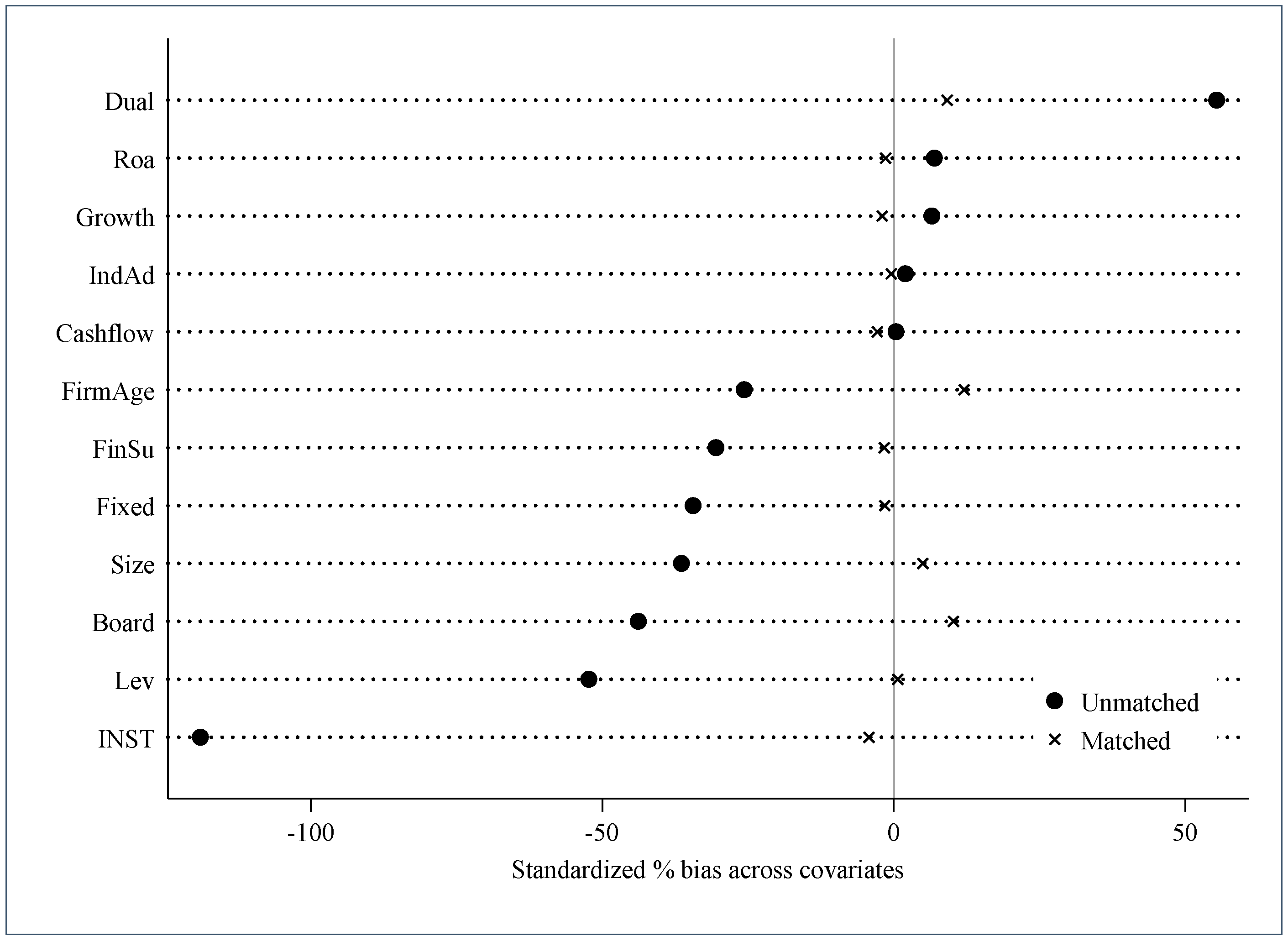

5.3.1. PSM Method

This study adopted the propensity score-matching method to address the bias caused by non-random selection. Specifically, This study employs the criterion of whether executive equity incentive levels surpass the highest point of an inverted U-shaped relationship. Organizations with incentive levels exceeding this threshold are classified as the experimental group, while the remaining sample functions as the control group. Thereafter, all control variables from Model (2) are regarded as covariates, and a 1:1 closest neighbor matching with replacement is performed. The results of the matching matches are shown in

Figure 1.

After eliminating samples beyond the common support region, a regression analysis was conducted. Column (1) in

Table 4 presents the regression results. The regression coefficients for

Incentive and

Incentive2 are 0.194 and −0.142, respectively, both significant at the 1% level.

5.3.2. Heckman Two-Stage Method

Executive stock incentives are typically driven by a company’s decisions. However, the formulation and execution of these incentives may be influenced by selection biases or other unobservable factors from the board of directors or compensation committee, leading to sample selection bias. To effectively mitigate the biases caused by selective implementation, this study employed the Heckman two-stage method (

J. Zhang et al., 2023). This research relies on two instrumental variables: the ratio of firms in an industry implementing executive share-based incentives to the total number of firms in that industry (

IncentiveIndi,t), and the ratio of firms in a company’s registered region adopting such incentives to the total number of firms in that region (

IncentiveProi,t). This methodology efficiently eliminates potential sample selection bias, consequently augmenting the accuracy of model estimations and the dependability of outcomes.

In the first stage, the dummy variable representing a firm’s acceptance of executive equity incentives performs as the dependent variable. Expanding on the control variables (

Controlsi,t) in Model (2), we integrate

IncentiveIndi,t and

IncentiveProi,t to formulate a Probit model, subsequently deriving the inverse Mills ratio (

Imr).In the second stage, the Probit model is constructed to calculate the inverse Mills ratio (

Imr). The regression results of the first and second stages are shown in Columns (2) and (3) of

Table 4, respectively. Column (2) shows that these two coefficients for

IncentiveIndi,t and

IncentiveProi,t are 4.048 and 3.598, respectively, both of which are significant at the 1% level, indicating that instrumental variable selection is effective. The results in Column (3) show that the coefficient of

Imr is 0.017, which is not significant, indicating that the possibility of sample selection bias is low. After controlling for

Imr,

Incentive, and

Incentive2, the two coefficients are 0.008 and −0.017, respectively, and are significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively, indicating that the conclusions of this study are still robust after alleviating the sample selection bias.

5.3.3. Instrumental Variable Method

There may be a bidirectional causal relationship or endogeneity issues caused by omitted variable bias between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience. In practice, enterprises with greater resilience may have a greater number of coping strategies and resources, which can result in a greater emphasis on long-term incentives and a greater influence on the design of their executive share-based incentive programs when faced with market volatility or crises. In contrast, the enterprise’s resilience may be influenced by the design of these incentive schemes.

This study uses the instrumental variable (IV) method to solve the bias caused by endogeneity problems. Specifically, we picked the mean level of executive equity incentives across the company’s industry and the square of this mean as instrumental factors for Incentive and Incentive2, respectively. The rationale for selecting these instrumental variables is as follows: Firstly, addressing relevance while creating equity incentive schemes, corporations frequently reference the equity incentive levels of executives within their industry. Consequently, the mean value of executive share incentives within the industry exerts a considerable influence on a company’s equity incentive decisions. Second, regarding exogeneity, the average equity incentive levels of executives in the same industry are calculated based on the average incentive levels of companies within the same industry, which have a minimal correlation with the specific organizational resilience of the company, thus meeting the exogeneity requirement.

Therefore, an instrumental variable test was conducted. The under-identification test revealed Anderson’s canonical correlation LM statistic of 190.77, accompanied by a

p-value of 0.00, signifying that the instrumental variables adequately identified the model. Second, the weak identification test showed a result of 95.88, which is significantly higher than the 10% critical value (7.03), indicating that the instrumental variables do not have weak identification issues. Finally,

Table 4, column (4) presents the results of the second-stage regression using instrumental variables. The results show that the coefficients for

Incentive and

Incentive2 are 1.529 and −1.686, respectively, and both are significant at the 1% level, indicating that the conclusions of this study are still robust.

6. Further Analysis

6.1. Mechanism Inspection

Based on behavioral agency theory and principal-agent theory, this study suggests that executive equity incentives have an inverted U-shaped influence on organizational resilience, with “agency cost” and “short-sighted management” acting as parallel pathways to promote and then inhibit the effect.

Along the agency cost path, moderate equity incentives may effectively align the interests of management and shareholders (

Jensen & Meckling, 1976), therefore diminishing monitoring expenses and residual losses resulting from target divergence. This results in CEOs being more inclined to engage in strategic initiatives that support long-term business competitiveness, so reinforcing the organization’s strategic focus and adaptability—organizational resilience. When incentive levels are beyond the optimal range, the “risk aversion transfer” effect, as delineated by behavioral agency theory, commences showing up. Excessive equity ownership may result in a disproportionate concentration of executives’ personal wealth within the company, making them too sensitive and risk-averse to potential short-term stock price fluctuations, including essential strategic reforms and long-term R&D investments. In such situations, management may use conservative measures to secure option returns by resisting essential organizational changes, or alternatively, engage in excessively risky investments to pursue maximum stock values at the time of exercise. Both practices will augment implicit agency costs and ultimately undermine organizational resilience.

In addition, concerning the myopic management strategy, modest equity incentives might align long-term value by reformulating executives’ goal-setting and risk-taking behaviors. Although equity constitutes a substantial portion of executives’ total wealth when incentive levels are appropriate, it is insufficient to distort their motivations for wealth accumulation. Despite uncertainty, leaders are more inclined to pursue strategic expenditures that increase the company’s long-term core competitiveness in order to protect and improve these future benefits (

Mao & Li, 2016;

W. Wu et al., 2024). In this context, management’s risk appetite transitions towards stability and long-term sustainability, aligning their interests with shareholders’ long-term objectives while effectively restraining short-term capital market returns. Excessive incentives, however, divert management’s focus from “value creation” to “maximizing personal benefits.” Faced with the pressures of exercise conditions and lock-up periods, CEOs feel obligated to artificially elevate stock values using many methods. This is demonstrated by both reducing R&D expenditures, which are essential for long-term growth, and allocating funds to short-cycle financial assets that yield rapid profits. The misallocation of resources and stagnation of innovation considerably diminish the company’s capacity to endure long-term disruptions and industry changes, undermining the basis of organizational resilience.

This study conducts mediation effect testing from two perspectives—agency costs and managerial myopia—to validate the aforementioned mechanisms. To assess agency costs, we employ

W. Chen’s (

2018) methodology, utilizing the management expense ratio (

Mfee = management expenses/total assets) as the primary proxy indicator. This measure indicates unproductive costs in daily activities. In situations characterized by information asymmetry and insufficient oversight, elevated management costs frequently signify opportunistic behaviors, like excessive consumption, redundant personnel, or resource misallocation (

Jensen, 1999), making it a commonly employed metric for first-category agency problems. To evaluate management myopia, we adopt

Y. Yu et al. (

2018) study framework, utilizing the ratio of current short-term investments to initial total assets

(Shortinv) to reflect fluctuations in managerial preferences towards future investments. Short-term investments generally exhibit elevated liquidity, little lock-up durations, and swift returns. When CEOs encounter demands for equity realization, they may prioritize short-term investments at the expense of R&D, human capital, or long-term projects, indicating a bias in their temporal preference favoring immediate returns.

This research conducts regression analysis on the two mediating variables based on Model (4) to further examine their mediating function in the impact of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience in firms.

The empirical results show that, in terms of agency costs, the coefficients for executive equity incentives (

Incentive) and its squared term (

Incentive2) in column (1) of

Table 5 are −0.027 and 0.028, respectively, both significant at the 5% level. This indicates a U-shaped relationship between executive equity incentives and the management expense ratio. When the incentive level is low, the agency problem gradually diminishes as incentive intensity increases. However, when the incentive level exceeds a certain threshold, the agency problem worsens. Column (2) shows that the management expense ratio is significantly negatively correlated with corporate organizational resilience, confirming that agency costs act as a mediating mechanism through which executive equity incentives influence organizational resilience.

In the management shortsightedness dimension, the coefficients of executive equity incentives and their squared terms in column (3) are −0.021 and 0.035, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. This finding suggests that there is a U-shaped relationship between executive equity incentives and short-term management. Column (4) further illustrates that the extent of managerial myopia shows a significant negative correlation with organizational resilience, suggesting that executive equity incentives have a non-linear impact on organizational resilience by initially eliminating and subsequently worsening managerial myopia. Therefore, managerial myopia serves as an intermediary mechanism by which executive equity incentives affect organizational resilience.

6.2. Heterogeneity Test

6.2.1. Property Rights of Enterprises

The theory of formal and real authority distribution proposed by

Aghion and Tirole (

1997) indicates a distinction in corporate decision-making between formal and actual authority. Private firms typically demonstrate governance efficiency and decision-making mechanisms characterized by distinct property rights, streamlined hierarchies, and shortened decision-making processes. This provides grants management with enhanced autonomy and flexibility in resource allocation, strategic modifications, and crisis response. By implementing moderate equity incentives, executives can promptly react to incentive signals by actively encouraging organizational resilience through optimizing capital structures, enhancing organizational learning, and maintaining redundant resources, thus magnifying the beneficial impacts of incentives. Conversely, state-owned firms are limited by multi-faceted evaluations, regulatory interventions, and complicated approval procedures. Despite the implementation of equitable incentives, their restricted strategic adaptability and operational efficacy lead to diminished incentive transmission mechanisms.

Furthermore, concerning the supervision and restraint mechanisms, executives in state-owned enterprises undergo limitations from various formal oversight systems, including the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), disciplinary inspection agencies, and audit inspection departments. Their career development is largely contingent upon political affiliations and the efficacy of policy execution, markedly diminishing short-term profit-driven incentives. As a result, despite high equity incentive levels, their actions are nonetheless largely sensible, deviating little from long-term development objectives and posing manageable agency issues. The effect of incentive intensity on organizational resilience is thus minimal. Conversely, even with the continual development of governance frameworks within private firms, they remain lacking independent and efficacious external oversight bodies. Challenges such as inadequate board independence and weakened supervisory board functions persist. This context has established a governance trait of “minimal external oversight—significant discretionary authority.” With moderate incentives, CEOs are inclined to select behavioral strategies that enhance organizational resilience after evaluating the advantages of proactive performance against the potential consequences of misconduct. Excessive incentives may result in higher profit expectations and diminished accountability, causing executives to exhibit opportunistic behavior, resulting in short-term decision-making and resource misallocation that intensifies managerial myopia and agency costs. This study forecasts that in private firms, the correlation between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience will continue to demonstrate an inverted “U” shape.

This study categorizes sample enterprises into state-owned and private entities based on ownership, and conducts a regression analysis on Model (2) for each category. Columns (1) and (2) of

Table 6 present the regression results. The results show that

Incentive and

Incentive2 in state-owned enterprise samples are not significant. The coefficients of

Incentive and

Incentive2 in the sample of private enterprises are 0.010 and −0.018, and both are significant at the 1% level. This indicates that in private enterprises, the impact of executive equity incentives on enterprise organizational resilience is more significant.

6.2.2. Financing Constraints

Agency theory and resource dependency theory suggest that in firms facing high financial constraints, management investment decisions encounter increased restrictions due to considerable challenges in obtaining external capital. In these situations, equity incentives can convey management’s confidence in the company’s future growth to external markets, effectively mitigating financing pressures and strengthening organizational resilience. In organizations with few financing limitations, capital liquidity increases and managerial decisions are less affected by the finance environment. Shareholder and market supervision systems effectively guarantee the long-term and stable conduct of management. In such conditions, the effectiveness of equality incentives is considerably reduced, exerting a relatively minor influence on organizational resilience. This research asserts that in organizations facing significant funding limitations, the correlation between executive equity incentives and corporate organizational resilience demonstrates an inverted U-shaped pattern.

This research use the FC index to assess the degree of financial constraints (

Ju et al., 2013;

Jiang et al., 2016). Utilizing the annual median financing constraint level across industries, the entire group of firms is categorized into two groups: those with higher financing restrictions and those with lower financing constraints. The regression outcomes for each group are displayed in columns (3) and (4) of

Table 6, respectively. The findings indicate that the coefficients for

Incentive and

Incentive2 are 0.013 and −0.024 and are significant at the 5% and 1% levels in the samples with considerable financial constraints. In the low-financing-constraint group, the coefficients were 0.004 and −0.014, respectively, with

Incentive demonstrating no significance and

Incentive2 being significant at the 1% level. The findings indicate that, even in firms with excellent financing conditions, beyond a particular amount of equity incentives could promote myopic and risk-seeking behaviors within management, substantially undermining organizational resilience. In contrast to the high-financing-constraint group, the coefficients are diminished, and the inverted “U” shaped curve demonstrates better stability.

6.2.3. Degree of Information Asymmetry

In an environment characterized by information asymmetry between shareholders and management, shareholders struggle to fully understand management’s decision-making and operational actions, leading to diminished trust in management. In these conditions, well-structured equity incentives can alleviate the trust deficit by matching the interests of shareholders and management. This alignment permits the effective distribution of resources and strengthens the organizational resilience of the firm. Conversely, the need for equity incentives is lessened and their influence on organizational resilience is reduced in organizations with greater transparency because shareholders have a greater understanding of internal decision-making and operations, which improves the effectiveness of the oversight mechanism. Therefore, this paper suggests that when information asymmetry is high, there is an inverted U relationship between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience.

By calculating the manipulative accrued items (

DAi,t) using the modified Jones model (

Y. Wang et al., 2009), the degree of information asymmetry of enterprises was calculated according to Equation (5).

Then, according to the industry median of the degree of information asymmetry, the entire sample was divided into high and low groups, and the regression results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of

Table 6. The results show that

Incentive and

Incentive2 are high in samples with a high degree of information asymmetry, with coefficients of 0.011 and −0.022, respectively, and both are significant at the 1% level. In samples with low information asymmetry,

Incentive and

Incentive2 are not significant, indicating that in enterprises with a high degree of information asymmetry, the impact of executive equity incentives on organizational resilience is more significant.

6.2.4. Degree of Economic Uncertainty

Firms operating in unpredictable economic conditions encounter considerable operational risks and market fluctuations, requiring adaptable strategic modifications to respond to changes. Equity incentives encourage executives to actively pursue market opportunities, swiftly adjust strategic positions, optimize resource allocation, and strengthen organizational resilience. However, when incentives are excessive, executives may be driven by short-term gains to make risky strategic decisions such as reckless expansion or over-investment. In a stable economic environment, the external risks and uncertainties faced by companies are relatively low and their strategies are more fixed, requiring fewer frequent adjustments to adapt to environmental changes. At this time, corporate risks are easier to manage and executives do not need to rely on the motivation provided by equity incentives to enhance organizational resilience. Therefore, the impact of equity incentives on organizational resilience is limited. This study suggests that, in an economy with high uncertainty, there is still an inverted U relationship between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience.

This study uses the method involves using the China Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, constructed by Baker et al. and jointly disclosed by Stanford University and the University of Chicago, to measure economic policy uncertainty (

Z. Wang et al., 2018). The whole sample was categorized into high and low groups according to the industry median of the economic policy uncertainty index, with separate regressions performed for each group. The regression findings are displayed in columns (7) and (8) of

Table 6. The results demonstrate that in the group characterized by a high economic policy uncertainty index, the coefficients for

Incentive and

Incentive2 were 0.013 and −0.028, respectively, both statistically significant at the 10% and 1% levels. In contrast, within the low uncertainty group, the coefficients for

Incentive and

Incentive2 were not statistically significant. The findings suggest that executive equity incentives are more successful in improving organizational resilience in companies facing significant economic policy uncertainty.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Organizational resilience, a crucial competency that allows companies to withstand environmental disruptions and facilitate recovery and reorganization, has garnered significant attention in recent years from strategic management and organizational theory disciplines. Current research predominantly focuses on the resource-based view and dynamic capability theory, highlighting the essential functions of redundant resources, absorptive capacity, and strategic flexibility while insufficiently addressing the crucial role of senior managers as proactive agents in threat identification, resource mobilization, and strategic restructuring. This paper examines data from China A-share listed companies between 2009 and 2023, presenting executive equity incentives as a corporate governance mechanism, which combines self-determination theory, dynamic capability theory, and upper echelons theory to systematically assess their influence on organizational resilience, resulting in the following conclusions: There exists a notable inverted U-shaped correlation between executive equity incentives and organizational resilience. This discovery enhances comprehension of incentive mechanisms through the motivational lens of self-determination theory. Moderate incentives enhance executives’ intrinsic motivation to develop dynamic capabilities by satisfying their needs for autonomy, competence, and belonging. Conversely, excessive incentives lead to external control, diminishing intrinsic motivation and fostering “controlling motives” focused on wealth maximization, which ultimately compromising the organization’s capacity to perceive, acquire, and reconfigure resources, thereby impairing organizational resilience. Then, effective internal control can markedly mitigate the curvature of this inverted U-shaped connection and advance its inflection point. This outcome broadens the scope of dynamic capacity theory, demonstrating that internal control, as a formal governance system, might reduce decision-making ambiguity arising from environmental unpredictability by offering stable rule support and clear information feedback. At moderate to low incentive levels, internal controls may offset the beneficial impacts of equitable incentives, allowing organizations to attain optimal resilience with less incentive intensity. At elevated incentive levels, they successfully mitigate opportunistic behaviors and guarantee the continuous advancement of dynamic capabilities. In addition, agency costs and managerial myopia function as fundamental mediating processes. This discovery clarifies the “black box” of senior management echelon theory: Equity incentives, as a principal executive motivator, affect agency actions and cognitive concentration, therefore resulting in organizational resilience results. This reveals the micro-level process of “executive characteristics → strategic actions → organizational performance.” Ultimately, heterogeneity analysis reveals that these incentive effects are more significant in private firms, particularly those facing more funding limitations, severe information asymmetry, and heightened economic policy uncertainty. These findings underscore the conditional nature of incentive mechanisms, confirming that executive incentives do not independently influence organizational resilience but are intricately integrated within corporate property rights frameworks and informational contexts. This offers empirical evidence for developing context-specific incentive theories.

In light of the aforementioned research findings, this paper presents the subsequent recommendations: Principle of Moderate Incentives. Policymakers are required to promote the implementation of the “moderate incentives” approach by firms, ensuring that the magnitude and extent of equity incentives correspond with the company’s developmental stage, market environment, and internal circumstances to mitigate adverse impacts caused by excessive incentives. Enhancing Internal Control. Internal control is essential for the proper execution of executive equity incentives, serving as the foundation of effective corporate operations. The government ought to enhance corporate internal control standards and recommendations, offering firms clear frameworks and reference points for the establishment of internal controls. Enterprises should proactively address government objectives by implementing robust internal control systems, which encompass a clear delineation of duties, stringent approval protocols, and efficient risk management strategies. Subsequently, due to the substantial differences in the efficacy of executive equity incentives among various firm types, governments and regulators ought to implement varied management strategies in policy development. Private enterprises facing significant financing constraints, elevated information asymmetry, or increased economic policy uncertainty should receive more flexible policy support, including fiscal subsidies and tax incentives, to mitigate financial pressures and effectively leverage equity incentives to bolster organizational resilience.

For state-owned enterprises and firms with better funding sources and greater transparency, constraints may be selectively loosened to foster the discovery of flexible incentive mechanisms, thereby supporting sustainable long-term growth. In the end, governments and businesses should collaboratively establish a conducive policy framework. The government ought to augment policy guidance and services for firms by offering essential policy consultations and training to facilitate their comprehension and implementation of pertinent policies. Simultaneously, firms should proactively offer feedback regarding the efficacy of equitable incentives and internal controls, establishing a constructive conversation with the government to cooperatively develop and refine policies.