Abstract

This paper examines the stock market reaction to company investment decisions with and without a sustainability objective. Abnormal returns are estimated using a standard event study methodology for a sample of 517 investment announcements for listed UK firms for the period 2013 to 2021. Using a sample of 90 sustainable investments and 427 non-sustainable investments, we test whether 90 announcements with a sustainability agenda are more positively viewed by market participants than 427 announcements without a sustainability agenda. This study documents significant positive stock market reactions to both sets of investments, but abnormal returns are higher for investments without a sustainability agenda. The difference in abnormal returns between both sets of investments is not statistically significant. The findings reported in this study suggest that classifying corporate investment decisions according to information content indicative of a sustainability agenda contains price-sensitive information. This has implications for information made available to the market and will therefore promote price discovery, reducing the information asymmetry between informed and uninformed investors and allowing improved market efficiency in categorizing investment decisions according to investment objectives. In a market-based system, the positive valuation of investments associated with sustainability undertakings has implications for allocative efficiency, because firms become more attractive regarding the future allocation of funds to investment projects that address sustainability concerns, indicating that new sustainable investments should be encouraged.

1. Introduction

This study assesses the stock market reaction to new investment announcements which can be classified as being consistent with the United Nations’ sustainable investment objectives.1 A sustainable investment in our framework is an investment project which addresses environmental concerns. The primary hypothesis is that the announcement of new sustainable investment will be positively received by market participants since such projects are compatible with modern stakeholder capitalism and the future success of the company and society as a whole. As such, they are desirable to market participants, and it might be expected that markets would reward such investments. A positive reaction indicates that such investment is encouraged by the market; hence, the allocative efficiency mechanism will ensure that funds flow to sustainable investment to the benefit of investors and society as a whole. The alternative hypothesis that investors do not value sustainable investments to the same degree as other investment projects without a sustainability objective is also tested (Burton et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). The alternative hypothesis indicates that investors expect sustainable investment to require a sacrifice of return compared to non-sustainable investments. If the alternative hypothesis is accepted, it would suggest that investors are not concerned with the benefits to society of sustainable investment and so such investment needs to be encouraged through other mechanisms and policies.

The present study investigates whether sustainable investments translate into stock price performance by asking whether sustainable investments are more positively viewed by market participants than other types of investments without evident links to a sustainability agenda. Using company investment announcements as the basis for investigation, this study updates prior UK studies on investment announcements (for example, Burton et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990) and extends the literature by examining the relationship between sustainable investment information and abnormal returns for a sample of company investment announcements. A standard event study methodology is used to estimate abnormal returns for a sample of 517 investments announced by listed UK firms for the period 2013 to 2021. Out of 517 qualifying company investment announcements, 90 observations are the relevant announcements addressing environmental concerns and are categorized as sustainable investments. The remaining 427 announcements are categorized as non-sustainable investments. The robustness of the results is confirmed using a set of confirmation checks relating to data, method, and variable construction.2 Woolridge and Snow (1990) and Jones et al. (2004) suggest that positive market reactions to investment announcements reward and encourage such investment, leading to the allocation of market funds to such projects in a market-based system of fund allocation. The findings from the current study reveal that, on average, the market rewards firms for investing in projects with sustainability-linked objectives at announcement. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing evidence on the stock market valuation of sustainable investments and identifies positive abnormal returns consistent with a positive valuation of new investments with a sustainability agenda. Prior studies focus on the impact of ESG activities on firm value using positive and negative news (see Flammer, 2013; Krüger, 2015; Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019; Ender & Brinckmann, 2019), whereas this study is focused directly on the extent to which markets encourage sustainable investment projects in their responses to the announcement of such activities. Other extant studies examine how governance rankings and other ESG performance scoring systems affect stock returns (Lo & Kwan, 2017; Taylor et al., 2018), while the present study explores the relationship between ESG scores and abnormal returns in the specific context of company investment announcements. A research note by G. Adamolekun et al. (2022) examines the effect of emissions on stock returns in a similar setting. However, our study is the first to classify investment decisions into those with a sustainability agenda and those without and to examine the links between sustainable investment and stock market returns. While debate goes on in the media and among political parties, particularly in the US, about the extent to which sustainability objectives should be the focus of new investment, this study confirms that markets see new sustainable investment as financially desirable and worthy of funding.3 Allocation of funds to new sustainable investments should be encouraged, not only for philanthropy but also for fiduciary and pecuniary reasons.

Our focus is on company investment decisions relating to environmental concerns considering environmental regulations and mandates issued by the UK government and regulatory bodies.4 However, in the cross-sectional analysis, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) credentials are examined, covering the three dimensions of sustainable investment so that results are potentially generalizable and comparable with prior studies. ESG information is increasingly employed by market participants to appraise the performance of firms and to gain insights into long-term value creation. Fewer than 20 companies included ESG data or sustainability information in their corporate reports in the 1990s (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018). The subsequent 25 years have witnessed a significant increase, leading to almost 9000 companies providing ESG information in the reports in 2016 (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018). Aureli et al. (2019) find that the publication of sustainability reports by firms is increasingly relevant, especially for reports released from 2013 onwards. In a survey that reflects the sentiments of mainstream investment professionals, Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018) reveal that relevance to investment performance is the main motive for investors’ use of ESG information. Investment professionals see ESG as an ethical responsibility, and others anticipate it becoming material in the future. However, there is also notable dissent to the stakeholder approach in the form of a minority of the respondents who opine that ESG considerations will violate their fiduciary duty to their stakeholders (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018).

ESG information has been a matter of voluntary disclosure in many geographical locations, only becoming a mandatory reporting requirement in 2017 after an EU Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU, 2014) was implemented that mandated certain large corporations to disclose non-financial and diversity information and include how they manage environmental and social issues. This is to foster transparency and consumer trust given that non-financial information is a continual undertaking by its nature (Directive 2014/95/EU, 2014). Therefore, understanding market reactions to sustainable investments is particularly relevant in the UK context considering evolving ESG disclosure mandates (such as the Net Zero Strategy 2021, the Environment Act 2021, and the Carbon Budget and Growth Delivery Plan 2025), including shifts in investor sentiment post-2015 Paris Agreement. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the empirical and theoretical links between investment announcements, ESG information, and abnormal returns. Section 3 outlines the data and methodology employed in this work. The findings are presented in Section 4, and Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Announcements and Stock Returns

The literature on announcements and stock returns focuses on understanding the factors that influence the market valuation of new information. Fama et al. (1969) suggest that specific kinds of information should be examined separately to observe the speed of adjustment of stock prices. The literature examines a variety of information regarding a firm’s corporate strategy. Such information is price-sensitive because its disclosure—for instance, company announcements—triggers actions by investors and results in changes in stock returns.

One key strand of the literature on company investment is that of strategic investment decisions and their effects on stock prices. Strategic investment decisions involve a current outflow of resources in return for payback at an uncertain time in the future (Woolridge & Snow, 1990). The stock market reacts positively and quickly to announcements of strategic investments (Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). The market reaction varies according to the type of investment that the firm undertakes. Previous studies categorize investments according to the characteristics of the project, such as the purpose of the activity (Chan et al., 1990; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990), value creation ability or option characteristics (Chung et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2004), the immediacy of income generation (Burton et al., 1999), and whether they are part of a strategic alliance or joint venture (Burton et al., 1999; Jones & Danbolt, 2004; Jones et al., 2004; McConnell & Nantell, 1985; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). Chan et al. (1990) posit that changes in stock prices are influenced by changes in investor expectations about the future earnings realizable from increasing R&D spending. Burton et al. (1999) identify earnings and dividends as potential impediments to subsequent capital expenditure. Firms may fail to meet the market’s anticipated value for long-term investments and growth prospects (Burton et al., 1999). In a similar vein, information about follow-on opportunities from an investment influences the market reaction to a new investment announcement (Jones et al., 2004). The market reaction is more favorable towards investments that generate future investment opportunities than those without, which carry less future growth potential (Chung et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2004). Jones et al. (2004) distinguish investment announcements that create growth opportunities from those that exercise growth options, and they report average abnormal returns of 2.01% for investments that create growth options and 0.23% for those that exercise growth options for a sample of UK firms.

Another relevant basis for the categorization of investment projects is the immediacy of generating cash. Burton et al. (1999) find that projects with immediate cash generation have a lower abnormal return (0.08%) compared to those categorized as not having immediate cash generation (0.5%), suggesting that UK investors favor firms that commit to long-term projects with expected income further into the future. Burton et al. (1999) contend that investments that immediately generate payoffs earn higher returns than those with payoffs further into the future. The market evaluates the anticipated payoff from an investment and determines whether the present value of the investment is greater than its cost such that share prices increase by an equivalent amount to the expected net gain. Otherwise, the expected gain is deemed to be already incorporated into the share price ahead of the news reaching the market. The potential benefits accruable to the investment are reflected in the stock prices such that there are insignificant returns upon announcement (Burton et al., 1999). This view supposes that investors anticipate periodic investments by firms and are therefore unsurprised by investment announcements. Previous studies also provide evidence that the stock market reacts positively to investments undertaken as part of a joint venture (Burton et al., 1999; Jones & Danbolt, 2004; McConnell & Nantell, 1985; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). Like mergers, firms form joint ventures for research and development, shared assets and resources, and asset construction to fulfil the objectives of capital investment projects (McConnell & Nantell, 1985; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). The relationship between joint ventures and stock returns is such that every GBP 1 spent on joint investment projects by the participating firms causes a rise in share price by at least GBP £0.2. This is equivalent to earning a fifth and a quarter of the joint project expenditure in share value, with the added benefit of the diversification of the risk exposure by the concerned firms (Burton et al., 1999).

2.2. Evidence from the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Literature

The market might react differently depending on whether ESG information is considered to be positive or negative news. For instance, environmental news could be positive if it involves an investment expenditure that is likely to create value, but it could be negative if it is damaging to the environment or if it involves the imposition of fines on firms. Similarly, social news might be positive when it supports a community or employees, and it could be considered negative when there is a consequential loss of livelihoods. Governance could be regarded as positive when it improves the quality of information provided to shareholders, but it is negative if it constitutes unethical practices (see Ender & Brinckmann, 2019 for the categorizations). Ender and Brinckmann (2019) posit that categorizing ESG by pillar (E, S, and G) gives a fairer view of the impact of ESG news, because a firm’s behavior may differ across categories relative to the industry. The ease of quantifying and integrating environmental and governance data into valuation models, compared to social data, makes the provision of both more compelling to market participants (Eccles et al., 2011; Lo & Kwan, 2017). Information should be available to the market relative to the specific information needs of market participants (Eccles et al., 2011). Therefore, pillar categorization generates objectivity and transparency based on the firm’s specific behavior concerning each category. The magnitude of stock reactions to ESG information varies (see Ender & Brinckmann, 2019; Flammer, 2013; Janney et al., 2009; Lo & Kwan, 2017; Yadav et al., 2016). The market generally rewards the adoption of initiatives and events with a positive perception, although these may be barely significant (Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019). On the other hand, firms are heavily penalized when the event presents as a perceived negative outcome such that it offsets built-up value from positive news (Janney et al., 2009; Krüger, 2015). This is particularly the case for firms with more prominent environmental activities.

Few studies on the ESG credentials of firms are market-related (see Haque & Ntim, 2020; Ramelli et al., 2021). These focus on the carbon emissions credentials of firms. The market values firms that engage in carbon reduction initiatives instead of penalizing those with extreme GHG emissions (Haque & Ntim, 2020). Using scope 1, scope 2, and scopes 1 and 2 to measure a firm’s carbon emissions, Ganda and Milondzo (2018) find a negative relationship with financial performance, particularly return on assets (ROA), return on investments (ROI), and return on sales (ROS). The findings of Ganda and Milondzo (2018) suggest that investments that incorporate sustainability initiatives that lower carbon emissions can impact a firm’s financial performance. On the other hand, Trinks et al. (2020) propose that carbon-efficient practices can be beneficial towards managing systematic risk, in addition to improving the profitability (ROA and Tobin’s Q) of a firm.

2.3. Theoretical Framework

To stay competitive and add value, firms undertake activities such as acquisitions, investing in new products, and research and development. Corporate strategists seek to fulfil these requirements, while, at the same time, the market expects periodic value-enhancing strategies from firms (Woolridge & Snow, 1990). Market participants have an expectation that companies will invest at the expected rate of return, which in turn is also the required rate of return. As a result, new announcements of investments by firms will not be entirely ‘surprising’ to the market. From the perspective of the efficient market hypothesis, stock prices adjust quickly to new information reaching the market, such that any additional value arising from the announcement is already impounded into stock prices (Fama et al., 1969). This is because the market’s appraisal of the announcement is expected to be fully reflected in stock prices almost immediately following the announcement. Gilson and Kraakman (1984) propose mechanisms by which information is incorporated into stock prices. The authors suggest that the determining factors include the information savviness of the market, market devices (for instance, observed trading and unusual price movements), the forecasts of market participants with heterogeneous information, regulations by market institutions that regulate the dissemination of information among traders, and the cognitive biases of investors. Information that is widely known is rapidly reflected in stock prices as predicted by efficient market theorists, while information known to a minority of traders will be reflected slowly in stock prices (Gilson & Kraakman, 2003). Applying this reasoning to investment announcements, the prediction is that the value of a firm’s stock will incorporate any new information regarding the net benefits from the investment at the time of the announcement. Our approach is consistent with the rational expectations hypothesis (see Woolridge & Snow, 1990). Upon announcement, market participants evaluate the expected gains, given the associated risks, and stock values will adjust upward or downward due to the buying and selling behavior reflecting the market’s appraisal of the investment announced. News of a firm’s sustainability activities could send mixed signals to the market. On average, markets would expect to value new investments positively, and positive sentiment towards sustainable investment should only support the demand for such stocks. A positive signal may result from the media attention and hype surrounding the sustainability domain (Orlitzky, 2013). This can enhance corporate legitimacy, whereby firms gain support from external stakeholders such as government institutions and improve access to financial resources for investment in future sustainability projects (Haque & Ntim, 2020). Management’s efforts at enhancing sustainability credentials send a positive signal to the market about the societal legitimacy of a firm (see Janney et al., 2009; Sison, 2009; Serafeim & Yoon, 2023), and any such investment decisions announced by the firm would be expected to be met with a positive market reaction.

However, McWilliams and Siegel (2000) argue that the benefits of engaging in sustainability activities will offset the associated marginal costs. Therefore, the relationship between sustainability performance and financial performance could remain neutral—the null hypothesis. Orlitzky (2013) suggests that sustainability activities have an uncertain influence on a firm’s economic performance and the hype surrounding sustainability may be insufficient to move the market. A neutral view would suggest that the market expects firms to conform to sustainability as an institutional norm and simply meet the required rate of return. In this case, the market’s expectation of investment performance is that the benefits arising from sustainability activities are already impounded into stock prices (rational expectations).

Flammer (2013) argues that the resource-based view depends on both the internal level of sustainability (i.e., the firm’s resources and capabilities) and the external norms of sustainability (for example, regulations and stakeholder attention to environmental concerns). The pressure on firms to establish responsibility towards environmental and social issues and compliance with governance requirements results in the enactment and implementation of internal policies to fulfil external regulations. The internal moderators and institutionalized norms potentially define the sustainability credentials of a firm. It is thus expected that firms incur expenditures towards projects with a sustainability impact. Such costs might be expected to result in lower market responses to sustainable investments than non-sustainable investments. Moreover, a negative signal could result and imply that investors find it difficult to process ‘soft‘ news contained in sustainable investment announcements compared to technical or financial news (Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019). Hence, an alternative hypothesis would be that markets react less positively to sustainable investment when it already anticipates investments to take place at the current required rate of return. Information such as transaction costs, which are not freely known to investors, information asymmetry between investors, and investors’ heterogeneous expectations of the implications of new price-sensitive information contribute to market inefficiency (Fama, 1970). From the perspective of agency theory, there are substantial costs associated with engaging in sustainable investment to improve sustainability credentials, and managers may be irresponsible by engaging in value-destroying activities at a detriment to shareholder value (Krüger, 2015).

H1:

Investment announcements with sustainability objectives receive more positive abnormal returns than those without sustainability objectives.

Grewal et al. (2020) suggest that there will be a stronger firm-specific information effect on stock returns associated with disclosures of sustainability information. This will be more pronounced for firms with better integration of sustainability actions with corporate strategy and those with greater exposure to sustainability issues (Grewal et al., 2020). The premise for this conjecture is that investors attempt to bridge gaps between ESG ratings and the implications for the market valuation of these ratings by assessing and interpreting sustainability information from firms incrementally (Grewal et al., 2020). This view implies that the market assigns value to ESG ratings and scores and may incorporate such valuation into stock prices. Therefore, we predict that a firm’s ESG credentials, given by its incorporation of sustainability issues, are impounded into the stock market’s valuation of other corporate information (such as the announcement of sustainable investments). On the other hand, Serafeim and Yoon (2023) argue that ESG information has predictive ability but the market fails to fully incorporate the differential effect into stock prices. Instead, the differential predictiveness of future sustainability information will gradually be impounded into stock prices (Serafeim & Yoon, 2023). However, Grewal et al. (2019) report a less negative stock market reaction to the EU mandate for ESG disclosures by large listed firms, especially for firms with higher ESG disclosures.

H2:

A firm’s environmental, social, and governance scores are positively associated with abnormal stock returns to sustainable investment announcements.

The relative quantities of firm-level, market-level, and industry-level information are determining factors for market valuations of new investment information (Grewal et al., 2020). For instance, Chan et al. (1990) find that firms operating in high-growth industries experience positive market reactions compared to those in low-growth industries where the market reaction is negative. This emphasizes the proposition that market participants analyze investment announcements based on their prospects for investment opportunities (Burton et al., 1999; Chan et al., 1990). Additionally, managers’ efforts at improving the ESG credentials of firms may be at the expense of shareholder value. For instance, Krüger (2015) ascribes negative investor reactions to positive ESG news to agency problems. Therefore, improved ESG credentials may not translate into shareholder value if the potential for agency costs is increased. However, due to the importance of ESG scores and engagement to firms relative to their industry peers (Ender & Brinckmann, 2019), differences in stock performance can be anticipated. We propose that the stock market will value firms on the higher end of the ESG score spectrum more than those on the lower end of the spectrum because management’s efforts at improving sustainability credentials are observable via the ESG score and will translate into improved valuation of investment decisions. However, Flammer (2013) posits that sustainability resources, especially environmental ones, generate decreasing marginal returns. Therefore, the benefits of additional sustainability implementations are less positive. Hence, the effect of ESG scores on the valuation of investments might be expected to be more pronounced for low-ESG firms than high-ESG firms. Such a finding would imply that sustainable practices are already priced into high-ESG firms but are a positive signal for low-ESG firms. The emissions score reflects management’s efficiency towards reducing environmental emissions resulting from a company’s production processes. If such processes are already in place, then the market may price them in already, but, if such processes are signaled by the new investment, or at least a change in attitude towards sustainability is signaled, then the new investment may be more highly valued. Similarly, a firm’s efficient use of resources corresponding to eco-efficient solutions that improve operational processes may be more highly valued if the general strategy is not previously priced into the market’s response. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H3a:

Abnormal returns to sustainable investments will be more pronounced for firms with low ESG scores.

H3b:

Abnormal returns to sustainable investments will be more pronounced for firms with low resource use efficiency scores.

H3c:

Abnormal returns to sustainable investments will be more pronounced for firms with low emissions scores.

3. Data and Methodology

The current study utilizes event study methodology to investigate the stock market reaction to company investment announcements.

3.1. Sample Selection Procedure

Company announcements are sourced from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) National Storage Mechanism (NSM) database. The FCA NSM database is a repository for all regulatory information and announcements that are disseminated by Primary Information Providers (PIPs) and listed issuers under the UK authority.5 Regulatory disclosures are searchable by keyword, category, company name, publication date, legal entity identifier, and PIP source, resulting in a robust repository of regulated company publications. Data are available from 2013, thus dictating the start date of the sampling period for the current study. The process of data screening initially began by collecting all company investment announcements from the NSM records for the period 2013 to 2021. The relevant categories that contained investment announcements were identified from the preceding literature, and an initial dataset of 8100 was produced.

The identification of the relevant categories is motivated by prior empirical studies of investment announcements (Burton et al., 1999; Chan et al., 1990; Chung et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). Although there are predefined categories in the FCA database, the announcements are categorized according to the definitions of capital expenditure, new product launch, and R&D. In keeping with the practice in the literature, announcements made by firms in the financial services industry are excluded. Announcements of corporate acquisitions are also excluded because the literature suggests that such announcements have a significant influence on stock returns (Bennett & Dam, 2018; Chan et al., 1997; McConnell & Nantell, 1985). In addition, announcements containing confounding events are excluded—for example, those announcing the appointment of senior executives, the disclosure of director dealings, the issue of shares, dividend notices, the release of results, and annual general meeting (AGM) statements occurring simultaneously with investment announcements and within one day on either side of the announcement date. Each announcement is examined for evidence of investment information. The final sample consists of 517 announcements made by 213 unique firms, which are categorized into capital expenditure, new product launches, and research and development (R&D). This indicates that an average of 2.5 announcements were made per firm during the period 2013 to 2021. The data screening procedure is outlined in Appendix A.

3.2. Categorizing Investment Announcements

The final dataset (n = 517) is grouped into 2 sets of categorizations. One categorization focuses on sustainability objectives, while the other focuses on the type of investment project. A framework adapted from Jones (2002) and O. Adamolekun (2020) is used to categorize investment announcements according to project activity, based on the definitions of capital expenditure, new product launches, and research and development as outlined below. Following the categorization of the final sample of 517 investment announcements, 186 are capital expenditures, 111 are new product launches, and 220 are research and development projects.

- Capital Expenditure

This is the expenditure used to fund the purchase or upgrade of fixed assets with a useful life of one year or more, such as plants, properties, land, buildings, or equipment. Therefore, announcements of acquisitions involving the exchange and issue of shares (as in corporate acquisitions) and those involving the transfer of trade from one firm to another (as in business combinations) are excluded from this category. Announcements under this category are extracted from the FCA National Storage Mechanism’s general announcement classification of acquisitions.

- b.

- New Product Launches

A product launch refers to the introduction of a new product or technological concept into the market. It involves the commercialization of innovative findings. Announcements under this category are sourced from the FCA National Storage Mechanism under the Product Launch classification.

- c.

- Research and Development (R&D)

R&D projects involve the acquisition of intellectual property (IP) rights, commitments of resources towards technological processes and innovation, the discovery of new products, the publication of results of research studies, evaluation assessments of discoveries, and updates on ongoing studies. It also includes development projects. A substantial proportion of the value of an R&D project is held in its options value and its ability to delay follow-on investments, shelving them into the future (Jones et al., 2004). The R&D investment announcements are sourced from the FCA National Storage Mechanism under the classification of research updates.

The European Union (EU) Sustainable Finance Action Plan highlights the need to establish a framework that facilitates sustainable investment by fostering economic activity that leads to sustainable and inclusive growth. The publication, released on 8 March 2018, proposes the creation of a unified taxonomy for economic activities that can be considered environmentally sustainable. The EU taxonomy is intended to stimulate and scale up sustainable investments based on the following environmental objectives: mitigating climate change, adapting to climate change, the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, transitioning to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and protecting and restoring biodiversity and ecosystems. However, the taxonomy regulation suggests that varied means may be required for the economic activity to contribute to each highlighted objective. In categorizing the observations according to sustainability objectives, the announcements extracted from the FCA NSM are read to identify evidence of links to the stated objectives. The sample announcements are categorized into those with and without evidence of links to environmental sustainability objectives. Each announcement is read for evidence of projects with a sustainability agenda. Chung et al. (1998) uses keywords such as capital expenditures, capital spending, capital outlays, planned expenditures, and long-term expenditures to locate 308 capital expenditure announcements via the Nexis/Lexis service. Flammer (2013) specifies pollution, radiation, contamination, hazardous waste, oil spill, recycling, ecosystem preservation, emission, and global warming as keywords on Factiva to locate articles about corporate environmental concerns. The search criteria results in a data sample of 273 containing eco-friendly and eco-harmful corporate events. Following Flammer (2013) and Chung et al. (1998), and using Python software (version 3.8.10) to clean the data, investment announcements with a sustainability agenda are identified using keywords that are linked to sustainability objectives. These are identifiable through the mentions of keywords such as biofuels, biogas, bioplastic, and biomass, including those investments targeted at converting waste to energy, carbon capture and storage, and emissions reduction. Accuracy is verified by manually checking the results of the keyword search to confirm that the investment announcements indeed contain sustainability-related investment projects. Out of 517 investment announcements, 90 have recurring themes around carbon capture, low-carbon solutions, decarbonization, low emissions, biofuels, biogas, bioplastic, and biomass. These observations are categorized as sustainable investments. The remaining 427 announcements have no evidence to support links to the above-stated environmental objectives, and these are categorized as non-sustainable investments. The framework for categorizing the data into sustainable and non-sustainable investments is defined below. Samples of investment announcements with sustainability objectives are presented in Appendix B.

Data Screening Procedure for Construction of Sustainable Investment Framework

- Announcements for the period 2013 to 2021, relating to the FCA NSM categories of ‘acquisition’, ‘product’, and ‘research update’, are extracted into CSV files containing the announcement date, company name, title of the announcement, project category, and a URL link to the announcement text.

- An initial review of a selection of the announcements is carried out to identify keywords relating to sustainability.

- An initial search query using ‘carbon’, ‘recycle’, ‘emission’, ‘plastic’, and ‘waste’ is generated, and all announcement URLs are run in the Python Windows Powershell application to filter out all announcements with the keywords occurring in the text. The impact of wildcards is considered in the search query to optimize the search output. Variants of the keywords are specified in the Python code strings; for example, carbon–decarbon–decarbonize–decarbonization. The search query returns a matched set and an unmatched set after Python ‘reads’ the title and body of the announcement text in the URL.

- The matched set of results is manually reviewed to ascertain the presence and the context of the keywords within the announcement text. Each announcement is read to further identify themes relating to sustainability and the EU environmental objectives—climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, the transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

- The announcements with evidence of sustainability relating to the keyword search have recurring themes around carbon capture, low-carbon solutions, decarbonization, low emissions, biofuels, biogas, bioplastic, and biomass.

| Screening Procedure | |

| Database | Financial Conduct Authority NSM database |

| Period | 2013 to 2021 |

| Search date | 16 February 2022 |

| Search query | ‘carbon’, ‘recycle’, ‘emission’, ‘plastic’, ‘waste’ |

| Data type | Company announcement URLs |

| Screening application | Python in Windows Powershell Command |

| Search sample | 517 |

| Query result | 90 |

3.3. Event Study Methodology

Extant studies in the literature use the event study methodology to examine the stock market’s reaction to company news, regulatory announcements, and firm-specific events (Burton et al., 1999; Chan et al., 1995; Chan et al., 1990; Ender & Brinckmann, 2019; Flammer, 2013; Janney et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2018; Woolridge & Snow, 1990; Yadav et al., 2016). The following specifications are defined for this study.

- Event Window

The current study specifies an event period of 5 days before and 5 days after the announcement to examine the effects of company investment announcements on abnormal returns. The literature suggests that a short event window yields better precision in detecting abnormal returns (Armitage, 1995; Strong, 1992). Therefore, to increase the chances of detecting abnormal returns, this study ensures that the observations are without contemporaneous events one day pre- and post-announcement date, as seen in Jones et al. (2004), but excluding contemporaneous events two days pre- and post-announcement date is also common in the literature (see Flammer, 2013).

- Expected Returns

Estimating the expected returns model requires an estimation period before the event of interest. The current study uses an estimation period of 260 days, ending 10 days before the event day, to estimate the individual alpha (α) and beta (β) coefficients for each firm (Brown & Warner, 1980). The alpha (α) and beta (β) coefficients are estimated using the intercept and slope functions to regress the firm’s stock returns with the market index returns over the 260-day estimation period. An estimation period of more than 100 days, typically between 200 and 300 days, is recommended for accurate estimation of the alpha (α) and beta (β) coefficients (Armitage, 1995). The return on the firm’s stock and the return on the market index are each matched and measured over the same trading days. The hypothetical returns expected for each stock had the event not taken place are estimated using the market-adjusted (index) model, the market model, and the Fama–French 3-factor model. The event period is excluded from the estimation period to prevent the event from influencing the estimation of the normal performance model parameters. Shorter event periods enhance the detection of abnormal returns (Armitage, 1995; Dyckman et al., 1984). Although a two-day event window is common (for example, Burton et al., 1999; Chan et al., 1995; Chan et al., 1990; Flammer, 2013; Woolridge & Snow, 1990), cumulating abnormal return is more suitable when the event date is uncertain (Armitage, 1995; Dyckman et al., 1984). However, determining the event date with precision using paired t-tests and non-parametric (Wilcoxon) tests is not uncommon in the literature (for example, Jones & Danbolt, 2004). Peterson (1989) highlights the importance of determining the event date as precisely as possible. Observations with high levels of inactive (thin) trading over several days are excluded because they are likely to introduce biases and inconsistencies in estimating the beta (Brown & Warner, 1985; Campbell et al., 1998).6

- Market-Adjusted (Index) Model

The market-adjusted (index) model assumes that the firm has the same risk characteristics as the stock market and therefore the expected return on the firm’s stock is the return on the market index (Strong, 1992).

where is the expected return for share i at time t, and is the return on the market index at time t. The abnormal return is calculated as the difference between the actual return on the firm’s stock and its expected return. Since the expected return is equal to the return on the market index , the abnormal return is as follows:

where is the abnormal return on share i at time t, and is the actual return on share i at time t. The FTSE All-Share index, an equally weighted index, is used as a proxy for the market return. Compared to a value-weighted index, an equally weighted index assigns the same importance to firms of all sizes within the index (Armitage, 1995; Strong, 1992).

- Market Model

The expected return for the market model is estimated as follows:

where α and β are the regression constant (intercept) and the slope of the regression line, respectively, for share i. The abnormal return is calculated as the difference between the actual return on the firm’s stock and its expected return:

- Fama–French Three-Factor Model

The Fama–French three-factor model measures a stock’s expected returns using the excess return on a portfolio of small stocks over a portfolio of large/big stocks (SMB) and the excess return on a portfolio of high market-to-book ratio over a portfolio of low market-to-book ratio (HML). The three factors—the market risk premium, size, and market-to-book ratio—capture the cross-sectional variation in the average stock returns (Fama & French, 1992). The expected return is estimated as follows:

where is the risk-free rate, is the market risk premium, (small minus big) is the historic excess returns of small-capitalization firms over large-capitalization firms, (high minus low) is the historic excess returns of value stocks (high market-to-book ratio) over growth stocks (low market-to-book ratio), and is the coefficient of each factor.

The linear regression framework of the market model of expected returns captures the firm-specific/idiosyncratic risk that is unaccounted for by the market return, assuming that stock returns are influenced by market forces and the idiosyncratic component specific to the stock, and the information signal is independent of the market return (Strong, 1992). However, it fails to account for additional risks that are capable of influencing stock returns and does not capture the cross-sectional variation in the average stock returns—for example, the market-to-book ratio and firm size. The Fama–French 3-factor model, which includes the market risk premium, firm size, and market-to-book ratio, accounts for the cross-sectional variation in stock returns (Fama & French, 1992). On the other hand, the market-adjusted (index) model assumes that the expected return of a stock is equal to the market return, ignoring any idiosyncratic risks and the influence of the firm size and market-to-book ratio on the average stock returns. Bearing these in mind, this study uses the market model as the preferred choice of expected returns model because it accounts for firm-specific risks that can be attributed to firm-specific events affecting the stock return. Moreover, the smaller cross-correlation that it produces across abnormal returns suggests that it offers more reliable statistical testing (Armitage, 1995; Brown & Warner, 1985; Strong, 1992).

Peterson (1989) notes that certain disclosure events, such as government regulations or a change in tax laws, may cause the concentration or clustering of events around a calendar time and an increase in the variance of abnormal returns because observations in the event period are less independent due to the cluster, thereby weakening the power to detect abnormal returns (Peterson, 1989). However, using expected returns models that adjust for market movements enhances the detection of abnormal returns (Brown & Warner, 1980; Peterson, 1989). This study uses three return-generating models—the index (market-adjusted) model, market model, and Fama–French 3-factor model—which account for market movements in all tests to ensure that events remain independent and that abnormal returns are easily detectable. Additionally, the removal of confounding events mitigates event clustering.

3.4. Empirical Model

The following regression models are specified to evaluate the relationship between abnormal returns to investment announcements and ESG variables.

- Model 1:

ARit = α0 + β1ESGit + β2Productit + β3Researchit + β4ROAit + β5levit + β6lnsizeit + β7M/Bit + Industry dummy + εit

- Model 2:

ARit = α0 + β1D_ESGit + β2Productit + β3Researchit + β4ROAit + β5levit + β6lnsizeit + β7M/Bit + Industry dummy + εit

The baseline regression models are presented using the total ESG score as the explanatory variable. However, other specifications of ESG variables are examined in separate models, due to the high multicollinearity between the ESG variables, by substituting ESG scores with the other ESG variables under investigation. The variables include the component (pillar) scores for environmental (Env), social (Social), and governance (Gov) and two key environmental measures—resource use efficiency (ResUse) and emissions scores. In Model 2, dummy variables , , , , and are assigned the values 1 and 0, similarly to the percentile ranking of ESG scores. A description of all variables is presented in Appendix C.

In Table 1, observations are split into those with sustainability objectives and those without. Two-sample t-tests are performed, grouped by variable, to compare the mean values of abnormal returns and firm-level variables for sustainable and non-sustainable investments. The abnormal returns differ by 0.32% and 0.55% for day t and days 0,+1, respectively, and are not significant. The mean difference for ROA and leverage significantly differs between sustainable and non-sustainable investments. The results also indicate a size effect between both groups of investments; sustainable investments have a mean total asset of GBP 58.6 bn, compared to GBP 5.3 bn for non-sustainable investments. The mean difference of 1.77 is significant (p < 0.1). The significant difference in firm size suggests that larger firms undertake sustainable investments, which may indicate that the internal resources of a firm impact sustainable corporate investment strategies (Kadapakkam et al., 1998). The distribution of abnormal returns by industry shows that firms in the energy and utility industry exhibit a larger proportion of abnormal returns to sustainable investments, suggesting that larger firms, particularly those operating in certain industry domains, are more likely to pursue sustainable investment projects. In our population, sustainable projects are conducted by larger firms on average, which may indicate that there are barriers to such projects for smaller firms. As previously noted, larger firms are mandated to disclose the management of environmental issues, whereas disclosure by smaller firms is voluntary. Hence, the market reaction is suggestive of these disclosure levels, signifying the onset of mandatory disclosures. Appendix D shows the distribution of abnormal returns by industry, including the proportionate breakdown between sustainable and non-sustainable investment. In Appendix E, summary statistics are presented for the sustainable and non-sustainable subsamples.

Table 1.

Mean difference between non-sustainable and sustainable investments.

4. Empirical Findings

This section discusses the results of the empirical tests of the hypothesis.

4.1. Univariate Analysis

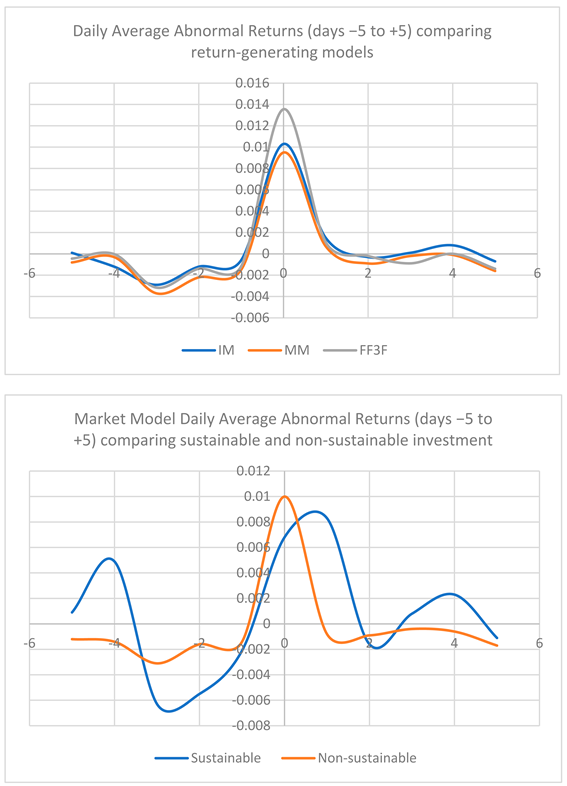

The daily abnormal returns are reported for the index (market-adjusted) model, the market model, and the Fama–French three-factor model for robustness in Table 2, Panel A. On event dayt, the average abnormal return is 1.03% for the index model, 0.95% for the market model, and 1.36% for the Fama–French three-factor model. The average abnormal returns are significant at the 1% level for the three expected return-generating mechanisms on the event day t. However, the daily abnormal returns are examined over the days before and after the event dates after the removal of contemporaneous events, which shows that the average abnormal returns are −0.06% and +0.15% on days t − 1 and t + 1, respectively, for the index model. This implies a lack of pre-announcement information leakage and the absence of a lagged effect spilling from the event date into the post-announcement period, one day after or beyond.

Table 2.

Daily abnormal returns.

However, an average abnormal return of −0.29% (p < 0.05) is observed on day t − 3 for the index model. Similar daily average abnormal returns on day t − 3 are reported for the market and the Fama–French three-factor models. The exclusions applied to data screening ensured the elimination of contemporaneous events one day before and one day after the event day t (Jones et al., 2004). Therefore, the significance observed on day t − 3 may indicate daily volatility and noise due to other contemporaneous events occurring outside the exclusion period (Feng, 2021). Instead, stock prices are fairly valued and reflect the new information reaching the marking following the announcement on the event day t. This is consistent with the predictions of the efficient market hypothesis. Therefore, the announcements are associated with abnormal stock returns, as found in prior studies (Burton et al., 1999; Chan et al., 1990; Chung et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990). In their study of the stock market reaction to the announcements of stock splits, Fama et al. (1969) provide evidence that the market’s assessment of new information is fully reflected in stock prices almost immediately following the announcement date. For the market model, abnormal returns are −0.15% on day t − 1, rising to 0.95% (p < 0.1%) on the announcement date and falling back to +0.07% on day t + 1. These results lend support to the theory that the stock market rapidly adjusts to new information following an announcement, and stock prices fully reflect the fair value of the stock after incorporating the effect of information contained in the investment announcement. The evidence presented here supports the notion of an efficient market (Fama et al., 1969) because there is no evidence of significant daily abnormal returns on the other days surrounding the announcement date. This result is robust to the three return-generating mechanisms.

The results of paired t-tests and Wilcoxon matched paired tests are given for the index model, the market model, and the Fama–French three-factor model in Table 2, Panel B, to establish the correct event window for the subsequent tests. For the index model, the mean difference between day t − 1 and day t is 1.06% (p < 0.01), and it is 0.85% (p < 0.01) between days t and t + 1. For the market model, the mean differences between days t − 1 and t and between days t and +1 are 1.07% (p < 0.01) and 0.85% (p < 0.01), respectively. For the Fama–French three-factor model, the mean difference between day t − 1 and day t is 1.47%, and it is 1.25% between days t and t + 1. Both the paired t-tests and the Wilcoxon matched paired tests suggest that the new information is impounded on day t. In Table 2, Panel B, we provide evidence that the effect that we are seeking is on day t. While we observe a significant effect on day t − 3, the return is very small and is not significantly different from that on day t − 2. Hence, abnormal returns on day t are used for the main analysis. The index model, the market model, and the Fama–French three-factor model confirm the choice of event window. Using daily returns data can potentially introduce bias and inconsistencies in the market model parameters when the stock returns and the market index returns are non-synchronous (Brown & Warner, 1985). However, the market model is retained as a preferred model of expected returns because it yields a more effective statistical test given the smaller variances in abnormal returns (Strong, 1992). The use of the market model is consistent with prior studies that utilize the event study methodology (see Ball & Brown, 1968; Burton et al., 1999; Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019; Chan et al., 1995; Chan et al., 1997; Chan et al., 1990; Ender & Brinckmann, 2019; Flammer, 2013; Lo & Kwan, 2017; Yadav et al., 2016).

The average abnormal returns for the different categories of investment announcements on day t are reported in Table 3. The overall sample has a mean AR of 0.95% (p < 0.01). The mean abnormal returns are 1.31% for R&D projects, 1.04% for product launch projects, and 0.45% for capital expenditure projects in a sample of 517 investment announcements from 2013 to 2021. Abnormal returns are significantly different from zero at the 1% significance level for all categories of investment when using both t-tests and Wilcoxon tests. As in prior studies, abnormal returns are positive and vary across the different investment categories. For instance, for a sample of 767 observations using the market-adjusted model, Woolridge and Snow (1990) report two-day cumulative abnormal returns of 1.13% for R&D projects, 0.69% for product launch projects, and 0.36% for capital expenditure projects, while Jones et al. (2004) report three-day cumulative abnormal returns of 2.2% for R&D projects, 1.9% for product launch projects, and 0.3% for asset expenditure projects for a sample of 402 investment announcements using market-adjusted returns. On the other hand, Burton et al. (1999) report two-day cumulative abnormal returns of 0.39% on a total of 499 capital expenditure announcements made between 1989 and 1991 using the market model. Meanwhile, Lee et al. (2016) report three-day cumulative abnormal returns of 3.9% for a sample of 243 new product pre-announcements over 9 years. When grouping the announcements into non-sustainable and sustainable investments, the mean abnormal return is 1.00% for non-sustainable investments (n = 427) and 0.68% for sustainable investments (n = 90). Both categories are significantly different from zero at the 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively. The reported CARs for the current study are consistent with prior studies on investment announcements and stock returns in terms of variation across different investment categories. The results corroborate the finding in the prior literature that R&D investments exhibit higher abnormal returns compared to product launch and capital expenditure investments based on the premise that the market assigns greater value to projects that create growth opportunities (Jones et al., 2004). Similarly, Chan et al. (1990) find evidence that an increase in R&D spending is associated with an increase in shareholder wealth.

Table 3.

Average abnormal returns.

Examining the proportions of positive and negative abnormal returns on the event day t reveals that 67% of the 517 observations show a positive reaction, compared to 33% exhibiting a negative reaction. For each of the investment categories, the proportion of positive to negative reactions is between 60% and 72%. In all cases, the z-statistics for a binomial sign test are significant (p < 0.01), thus confirming that the reported abnormal returns are not influenced by large changes in stock prices from a small proportion of stock and do not arise from extreme values (Chan et al., 1990). Overall, the results support our prediction of positive abnormal returns. For comparison, cumulative abnormal returns over a 2-day event window (day 0,+1) are reported in Appendix F, and plots of abnormal returns are provided in Appendix G for the full sample of 517 observations, comparing abnormal returns between return-generating models and between sustainable and non-sustainable investments.

4.2. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Abnormal Returns to Sustainable Investment Announcements

In Table 4, we examine whether a firm’s ESG credentials impact the abnormal returns to sustainable investments.7 We report significant negative effects on abnormal returns for each of the ESG credentials in Models 1 to 4 of Panel A in Table 4, except for governance scores, for which the negative coefficient is insignificant. Although the coefficients are small, the ESG scores, environmental scores, and social scores are significant at the 1% level. In Panel B of Table 4, the regression of abnormal returns with resource use efficiency and emissions scores shows negative effects that are significant at the 1% level in Models 1 and 2. Notably, the dummy investment categories reveal positive coefficients for the product launch category, which is significant at the 5% level in the model containing the resource use efficiency score but only at the 10% level in the model containing the emissions score. This finding is consistent with the view that the type of investment project is a determining factor for abnormal returns (Jones et al., 2004), and this finding confirms, for our sample, that it is relevant to the valuation of sustainable investment. Flammer (2013) posits that the more firms improve their sustainability, the more difficult it becomes to improve further. Our findings lend support to Flammer’s view. The rational expectations theory implies that a firm’s ESG activities are already impounded into stock prices, in accordance with industrial and institutional expectations (Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019). Therefore, efforts to improve credentials will gradually decrease marginal improvements (Flammer, 2013). Our findings support this conjecture. Although information asymmetry may be reduced because management’s efforts at improving ESG credentials are directly observable via their ESG scores, regarding Hypothesis H2, our results support the alternative hypothesis, which proposes negative associations of ESG credentials with abnormal returns to sustainable investment announcements. The evidence also supports the view that ESG information is not fully incorporated into stock prices at the announcement of sustainable investments (see Serafeim & Yoon, 2023).

Table 4.

Regression of ESG credentials and abnormal returns to sustainable and non-sustainable investment.

The pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for the non-sustainable investment subsample is reported in Models 5 to 8 in Panel B. Although all ESG variables show no statistical significance, the findings are consistent in part with the predictions of Hypothesis H2, which proposes a positive association of ESG credentials with abnormal returns. From the perspective of institutional theory, the market positively values firms with societal legitimacy because it projects management’s efforts at improving the ESG credentials of a firm (Janney et al., 2009; Sison, 2009; Serafeim & Yoon, 2023). Moreover, since the ESG credentials are directly observable by investors, the agency cost of monitoring is potentially reduced, and investors will have a stronger affinity for firms with strong credentials. Our findings suggest that any attempt at improving ESG credentials places firms at a fairer advantage with investors and can ultimately improve shareholder value.

Compared to sustainable investments where the ESG credentials are statistically significant and negatively associated with abnormal returns, non-sustainable investments show positive associations that are not statistically significant.

4.3. Analysis of ESG Credentials for Low-ESG and High-ESG Groups

The results of the OLS pooled regressions are presented in Table 5. In Models 1 to 4 (Panel A), the individual ESG credentials as independent variables are regressed with abnormal returns for the sustainable investment subsample. The low ESG score and low environmental dummy have positive and significant associations with abnormal returns. In Models 1 and 2 of Panel B, low resource use and low emissions are significantly and positively associated with abnormal returns. Of all the ESG credentials examined in the study, the resource use efficiency score has the highest coefficient of over 2%, suggesting that improving efficiency generates higher increases in abnormal returns compared to the other credentials for our set of investments. Serafeim and Yoon (2023) posit that the effect of ESG scores (ratings) on news events may be clouded by noise, and management’s efforts at improving the firm’s sustainability credentials may not be easy to detect in short-term stock price performance. Overall, the findings reported support Hypothesis H3 for the groups with low ESG, low resource use efficiency, and low emissions in the sustainable investment subsample. The effect of ESG credentials on the market reaction is stronger when there is more potential for improvement in ESG engagement by the firm, i.e., when ESG scores are lower. This finding supports the views of Ioannou and Serafeim (2019) and Grewal et al. (2020), who contend that higher voluntary disclosures are prevalent in firms with weak sustainability performance because these firms seek legitimacy by conforming to institutional and normative pressures.

Table 5.

Regression of ESG credentials and abnormal returns for low and high groups regarding ESG credentials.

For the non-sustainable investment subsample, a positive and significant (p < 0.05) association is reported for low ESG scores and low environmental scores, while a low social score shows no statistical significance. On the other hand, a low governance score shows a weak negative association (p < 0.10) with abnormal returns. Specific environmental metrics—resource use efficiency scores and emissions scores—are examined in Models (3) and (4) of Panel B. In both cases, the relationship with abnormal returns is negative. However, significance at the 10% level is reported for low emissions scores in Model 4. The relationship between low resource use and abnormal returns is not significant. Feng (2021) attributes the variation between low-ESG and high-ESG firms to higher integration costs experienced by low-ESG acquirers if the target firm’s ESG scores increase. We contend that high-ESG firms are compelled to internalize unexpected costs associated with consistently incorporating sustainability issues, whereas the unexpected costs of reducing emissions may be more impactful for low-emissions firms.

The findings show that emissions scores carry greater price relevant information, whereas the market’s valuations of high ESG scores and high resource use efficiency scores are weaker. The implication is that investors are willing to pay a premium for a higher emissions performance, but not for higher ESG scores or higher resource use efficiency (see Yadav et al., 2016). This suggests that a firm’s efforts at reducing emissions are more relevant to investment decisions and there is varying importance between environmental concerns. Firms in the high-emissions spectrum are likely to constantly disclose efforts at emissions reduction, and, from the organizational legitimacy perspective, their sustainability profile and visibility improve despite their emissions intensity. Therefore, disclosing efforts towards emission reduction will be perceived favorably by the market. This suggests that larger firms have stronger credentials because larger firms have larger resources to invest in improving their credentials (D’Amato et al., 2021; Drempetic et al., 2020). From the perspective of institutional theory, increased resources and consistent (mandatory) reporting by larger firms improve their profiles and institutional legitimacy (D’Amato et al., 2021).

Similarly to those for sustainable investment, the findings suggest that abnormal returns are more pronounced for firms with low ESG scores and low environmental scores in the non-sustainable investment subsample. However, the findings are consistent with Hypothesis H3 for the groups with low resource use, low emissions and non-sustainable investment. The significance (p < 0.10) reported for the low-emissions group implies that investors perceive firms with weaker emissions scores as not making sufficient effort to control emissions and may therefore penalize such firms.

4.4. Tests of Endogeneity

We used a detailed multivariate analysis in Section 4.2, which deals with some issues of causality. Fixed effects were included, which captured some potentially omitted variables; reverse causality is unlikely due to the chronological and residual nature of the tests. Selection issues are more complex as the sample is a population, but the population may have underlying characteristics that are not captured by univariate tests. Measurement error is also possible, but we use the most appropriate available methods for the calculation of variables, and the data are from standard data repositories. To mitigate the potential endogenous effects between ESG scores and abnormal returns to investment announcements, tests of endogeneity are performed using the two-stage Heckman sample selection and the two-stage least squares (2SLS) model. The Heckman estimation can be applied to statistical models to account for sample selection bias, limited dependent variables, and simultaneous equation models containing dummy endogenous variables (Heckman, 1979). The predicted lagged abnormal returns estimate is used as the instrument to control for the effect of past returns on the relationship between ESG scores and abnormal returns to investment announcements. For our sample, the findings suggest that abnormal returns to investment announcements on day t are not affected by the lagged values of abnormal returns, suggesting that reverse causality is unlikely and sample selection bias does not affect our results. The models produce consistent results when alternative return-generating mechanisms are applied, namely the index model and the Fama–French three-factor model, and using the market model with a two-day event window.

4.5. Other Robustness Checks

To check the robustness of our analyses, all regression models in the main findings are re-estimated using the market-adjusted (index) model for the event day t. The results show that the impact of ESG credentials on abnormal returns to sustainable investments on the event day t is similar in direction, magnitude, and significance for the index model to those reported for the market model. In addition, all regression models are re-estimated using a two-day event window (t, t + 1) for the market model to examine the effects of ESG credentials on abnormal returns to sustainable investments. The findings are similar in direction and magnitude to those reported using the market model (day t) test in the main analyses. However, we find some weakening of confidence levels. For instance, environmental scores are significant at the 1% level on the event day t, whereas we find significance at the 5% level using the two-day event window (t, t + 1). This may be due to the lack of information content on day t + 1. These results confirm that our selection of day t as the event window is correct. Further robustness checks are carried out by re-estimating all regression analyses using the Fama–French three-factor model on day t. The results are robust to those of the market model (day t) analyses. Moreover, the results of the low categorizations using the Fama–French three-factor model (day t) are similar in direction, magnitude, and significance to the main results reported for the market model (day t). The effect of outliers is examined by winsorizing the data at 1%. The results remain consistent with the previous estimates. For brevity, we do not provide tables for the robustness checks.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Areas for Future Research

5.1. Conclusions

This study analyzes the market model returns for a sample of 517 corporate investments announced by UK-listed firms for the period 2013 to 2021. The positive mean abnormal return of 0.95% for the whole dataset is consistent with prior studies on investment announcements (Burton et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2004; Woolridge & Snow, 1990) and indicates that investment is generally encouraged by the UK market. Our framework classifies announcements into those with a sustainability agenda (sustainable investments) and those without (non-sustainable investments). Of the 517 observations, 90 are classified as announcements of sustainable investments, and the remaining 427 are classified as non-sustainable investments. The mean abnormal return of 0.68% for sustainable investments confirms the positive valuation of new sustainable investments, consistent with findings regarding other types of sustainability disclosure (Flammer, 2013; Janney et al., 2009; Yadav et al., 2016). The results also indicate support for the efficient pricing of sustainable investment despite some recognized difficulties inherent in the ability of markets to price in sustainability information (Feng, 2021; Serafeim & Yoon, 2023). Investments with sustainability objectives are impounded rapidly into stock prices at announcement, contrary to the argument that the market may receive sustainability news unfavorably due to information asymmetry resulting from managerial expediency (see Capelle-Blancard & Petit, 2019). The mean abnormal returns for the sample of non-sustainable investments is slightly higher, at 1.0%, than for the sample of sustainable investments. However, the difference in the mean abnormal returns between the samples of sustainable and non-sustainable investment is not statistically significant.

The cross-sectional analysis reveals significant findings about the influence of a firm’s ESG credentials on the market’s valuation of sustainable investments. ESG scores, environmental scores, and social scores are found to negatively affect abnormal returns to new sustainable investments. We also find significant negative relationships between alternative environmental measures (resource use efficiency scores and emissions scores) and abnormal returns in our main tests. Higher returns for companies with lower ESG scores, combined with an overall positive abnormal response to sustainable investment announcements, imply that markets see the incremental value of new sustainable investments as being higher for companies with lower ESG scores—or, in our context, lower ESG credentials.

This study of a small but comprehensive sample of sustainable investments indicates that the market values sustainable investments positively, but slightly less than other investments without a sustainable agenda. This study addresses the research question of whether the stock market encourages sustainability by providing evidence of positive and significant abnormal returns to sustainable investments. However, investments without a sustainability agenda are more positively viewed by market participants than those with a sustainability agenda. The findings reported in this study have implications for allocative efficiency and suggest that sustainable investments should be encouraged. Pursuing investments in projects with a sustainability agenda will improve the future allocation of funds to such projects.

Classifying investment decisions according to the information content that signifies a sustainability agenda involves price-sensitive information. This has implications for information made available to the market and will promote price discovery. Moreover, investment objectives are identified as important factors for firms to consider when undertaking investment decisions. Information asymmetry between informed and uninformed investors might be reduced, and market efficiency could be enhanced by categorizing according to investment objectives. Therefore, in the face of rising sustainability investment undertakings resulting from disclosure mandates, policymakers may wish to consider this set of investment classifications to encourage sustainable investment. Initiating and pursuing well-designed sustainability investment projects will enhance the stability of financial systems and improve market efficiency. In turn, firms become more attractive regarding the future allocation of funds to projects that address sustainability concerns. At a national level, implementing policies that support sustainability objectives improves economic resilience and attracts foreign investment. The findings documented in this study suggest that the government should create incentives that promote institutional harmonization—for example, preferential tax treatment and increased funding for undertaking innovative projects that accommodate the ESG concerns of firms relative to their industry needs. When firms are encouraged through government incentives and subsidies and more funds flow towards sustainable investment projects, the overall market perception of such investments improves regardless of a firm’s level of ESG engagement. By implementing policies that encourage sustainable investment, firms are guided towards environmentally sustainable economic activities that align with sustainable finance regulations (e.g., the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities or the UK Green Finance Strategy).

These findings indicate that new sustainable investments should be encouraged for pecuniary reasons through tax allowances or subsidies to offset any costs associated with sustainability undertakings.

5.2. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

First, the keyword classification framework employed in this study relies on specified keywords. Although this classification method is relevant to small datasets, future research could leverage advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques or cross-validation by multiple coders to enhance the accuracy of the search results, especially in very large datasets.

Second, the working sample size for sustainable investment reflects the reporting environment between 2013 and 2021, when sustainability disclosure was mostly voluntary, and is therefore of limited size and constrains statistical power. Evidence suggests that the prevalence of ESG information increased in 2013 (Aureli et al., 2019). Future studies could update the current study and examine how the stock market’s valuation of sustainable investment has evolved. Being the first study to examine sustainable investment using a unique categorization framework, this study sets a precedent for the examination of the trends in sustainable investment in the future. Further work should seek to compare market reactions to sustainable investments in markets other than the UK. Markets are characterized by different factors, including economic growth drivers and liquidity. Therefore, examining the market’s valuation of sustainable investment decisions will offer useful insights into how international markets perceive this type of investment decision. This can foster economic and financial market efficiency and encourage foreign and institutional investments.

Third, the data on ESG credentials were also limited to credentials with available firm-level data points, restricting the sample size. However, the increasing trend in ESG engagement and the LSE mandate requiring all firms listed on the main market to report their activities regarding greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) indicate that more firms will be transparent about their ESG engagement. This opens up opportunities for the exploration of a broader range of ESG credentials in future research by targeting credentials relevant to industry groups and firm operations. This will ensure that findings are directly applicable to a firm’s ESG relevance and operational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J. and K.O.L.; Methodology, E.J. and K.O.L.; Software, K.O.L.; Validation, K.O.L. and E.J.; Formal Analysis, K.O.L.; Investigation, K.O.L.; Resources, K.O.L., E.J. and L.L.; Data Curation, K.O.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.O.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.J., K.O.L. and L.L.; Visualization, K.O.L.; Supervision, E.J. and L.L.; Project Administration, E.J. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization to conduct this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Appendix A. Data Screening Procedure

| Data Screening Procedure | |

| Initial dataset | 8100 |

| Announcements made by financial services firms | (1669) |

| Announcements of corporate acquisitions | (4132) |

| Non-qualifying announcements8 | (1279) |

| Confounding events9 | (468) |

| Announcements with incomplete stock data | (35) |

| Final dataset | 517 |

Appendix B. Extracts of Sustainable Investment Announcements

- i.

- An extract of an investment announcement with environmental sustainability objectives under the capital expenditure category is as follows.

Announcement Extract from the FCA National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk)

“Acquisition of gasification waste-to-energy plant in Croatia: