Abstract

The field of sustainable finance has grown rapidly in response to escalating climate and economic challenges, yet its intellectual landscape, especially the connectedness between green and traditional financial systems, remains underexplored. This paper aims to systematically map the evolution, thematic structure, and intellectual linkages of the sustainable finance literature with a specific focus on risk spillovers and connectedness across financial systems. This study employs a comprehensive bibliometric methodology to map 1261 Web of Science-indexed articles (1994–2024) on the connectedness of sustainable finance, using techniques such as citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, co-citation analysis, trend cartography, collaboration network, and keyword trend analysis. The study clarifies the field’s evolution and identifies its key themes, influential authors, institutions, and networks. The findings reveal an exponential surge in sustainable finance research after 2015, coinciding with policy milestones like the Paris Agreement and rising ESG investment interest. Notably, the review uncovers how research clusters have formed around topics such as green bond market spillovers, green technology innovation, and climate risk, highlighting both well-established areas and emerging fronts. The contribution lies in providing a roadmap for future research and policy: the study pinpoints knowledge gaps (e.g., systemic risk transmission between green and conventional assets) and suggests how policymakers and investors can leverage these insights to foster a resilient, sustainable financial system.

Keywords:

sustainable finance; connectedness; bibliometric analysis; ESG; systematic risk; green investing; market dynamics JEL Classification:

G20; G30; Q56; M14; C80

1. Introduction

The escalating challenges of climate change and the urgent need for sustainable economic growth have catalyzed interest in sustainable finance, which integrates environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into investment decisions. Governments and investors increasingly recognize that aligning financial systems with sustainability goals is crucial for mitigating climate change and promoting stable economic growth (Ayaz & Zahid, 2024; Barua & Chiesa, 2019; Ikevuje et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2022; Stern, 2013). Sustainable finance, particularly green finance, not only promotes investments that are environmentally responsible but also has a significant role in mitigating financial risks associated with environmental volatility and regulatory shifts (Ikevuje et al., 2024).

Recent studies highlight that the financial sector’s alignment with sustainable practices is critical to achieving international climate targets, particularly the goals set forth in the Paris Agreement (OECD/IEA, 2017; Ding et al., 2019). Green financial instruments, such as green bonds and renewable energy investments, are at the forefront of this transition, offering pathways to support global decarbonization efforts (Barua & Chiesa, 2019; Bhutta et al., 2022; Huang, 2024).

However, the interconnectedness and risk transmission mechanisms between green and traditional financial markets remain underexplored, particularly in terms of how systemic risk propagates through these channels under financial stress (Deng et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2024; Sachs et al., 2019).

Bibliometric analysis, which systematically maps scholarly output to identify thematic trends and research gaps, is a powerful tool for structuring and synthesizing the fragmented literature in the connectedness of sustainable finance (Boyack & Klavans, 2010; W. B. Luo et al., 2022) Through quantitative citation analysis and bibliometric reviews, we can provide an objective approach to understanding research development over time, pinpointing influential publications, and visualizing relationships between key topics, institutions, and authors (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; Barua & Chiesa, 2019; Boyack & Klavans, 2010).

Despite the burgeoning literature on the connectedness of sustainable finance, significant knowledge gaps remain in understanding its broader systemic impacts, particularly concerning risk transmission between green and conventional financial assets. Prior studies have examined segments of sustainable finance—e.g., corporate ESG performance (Gillan et al., 2021), green finance in emerging markets (Bhatnagar & Sharma, 2022), and climate finance mechanisms (Deng et al., 2022; W. B. Luo et al., 2022). However, a holistic understanding of the field’s structure and systemic implications is lacking. In particular, the interconnectedness and risk transmission between green assets (like clean energy stocks or green bonds) and conventional financial markets remains under-studied (Meng et al., 2024; Sachs et al., 2019). Questions persist on how shocks propagate across sustainable and traditional investments. For instance, do green assets provide safe havens during market stress, or could they transmit new risks? Recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and energy market volatility have further underscored the need to understand these linkages, as researchers observed distinctive spillover patterns (e.g., green bonds showing hedging properties against oil price shocks (Mokni et al., 2022).

Yet, the existing literature has addressed these issues only partially, often focusing on narrow subsets of the data or specific timeframes. Moreover, while several bibliometric reviews of sustainable finance have appeared, they either center on particular themes or cover limited periods. For example, (Cunha et al., 2021) outline sustainable finance research agendas but emphasize thematic framing over network structure; (W. B. Luo et al., 2022) map sustainable finance’s evolution up to 2021 but do not delve into author networks or risk-related subthemes; and (Kumar et al., 2022) leverage machine learning to review the sustainable finance literature but focus largely on broad topical clusters. Recent bibliometric studies underscore the need for a comprehensive evaluation of the connectedness of the sustainable finance literature to guide both policy and investment (Ayaz & Zahid, 2024; Bahoo et al., 2020; Bhatnagar & Sharma, 2022; Bhutta et al., 2022; Cunha et al., 2021; Ikevuje et al., 2024; A. Khan et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2022; W. B. Luo et al., 2022; Mbarki et al., 2023; Mi’raj & Ulev, 2024; Rabbani et al., 2024). These studies accentuate the importance of bibliometric analysis in this field, yet none have specifically traced the connectivity and spillover aspects within sustainable finance scholarship—a niche this paper aims to fill. We adopt a bibliometric lens to systematically analyze how sustainable finance research is interconnected, thereby identifying influential works and hidden linkages that traditional narrative reviews might miss. This approach allows us to capture the field’s intellectual structure, including cross-disciplinary influences (e.g., energy economics, environmental policy, corporate finance) that shape the discourse on sustainable finance and risk.

In the context of sustainable finance, bibliometric analysis helps capture the evolving focus areas—from early discussions on green investment returns to contemporary inquiries into green risk contagion and policy impacts—thereby highlighting both the academic progression and practical challenges of green finance (Bhutta et al., 2022; Bourcet, 2020; Elie et al., 2021; Losse & Geissdoerfer, 2021; Naeem et al., 2022; Trotta et al., 2024; Woon et al., 2023).

Our research addresses the following gap: How has the academic literature on sustainable finance evolved in terms of key themes and connectivity, and what does this imply for understanding systemic risks and guiding economic policy? The study responds by conducting a large-scale bibliometric analysis that not only charts publication trends but also unpacks the networks of citations and collaborations underpinning this field.

This study, therefore, discusses these gaps by conducting a comprehensive bibliometric review of the connectedness of sustainable finance research from 1994 to 2024, analyzing 1261 peer-reviewed articles from the Web of Science Core Collection to identify key trends, influential sources, and underexplored topics. Specifically, this analysis maps the scholarly landscape of interconnected themes such as green bonds, renewable energy, and systemic risk, thereby providing a foundational understanding of how the connectedness of sustainable finance research has evolved in response to global environmental and policy challenges.

This study seeks to delineate the beginnings of sustainable finance research connectivity, examine prevailing trends, and ascertain future potential. To fulfill this objective, the study examined the subsequent research questions:

Research Question-1: How has the domain of sustainable financial interconnectedness progressed from 1994 to 2024, and what are the prevailing themes and tendencies within this field?

Research Question-2: Which authors, organizations, countries, and publications most significantly contribute to the interconnectedness of sustainable finance research?

Research Question-3: What are the aims of important studies regarding the interrelation of sustainable finance, and which key ideas are utilized in these investigations?

Research Question-4: What are the future projections for the interrelation of sustainable finance research?

To clearly articulate the focus, the study outlines the objectives of this review:

(1) Map the evolution of sustainable finance scholarship: the review quantifies the growth of publications over time and identifies driving forces behind notable surges (e.g., policy events, market trends). This reveals how external developments (like climate agreements or ESG regulation) have influenced academic output.

(2) Identify influential contributors and knowledge networks: Using citation analysis, the review determines which authors, institutions, countries, and journals have shaped the field. The review also examines co-authorship and citation networks to see how ideas diffuse and which scholars act as knowledge bridges across subfields.

(3) Uncover key thematic clusters and intellectual structure: Through co-citation and keyword co-occurrence analyses, the review detects the major research themes (e.g., green bonds, renewable energy finance, ESG investing, climate risk) and how they interrelate. This helps to highlight dominant theoretical frameworks and emerging topics in the sustainable finance literature.

(4) Draw insights for policy and future research: By synthesizing these bibliometric findings, the study discusses their implications for sustainable finance practice and policy (such as financial regulation, risk management, and sustainable investment strategies). The research also pinpoints gaps and proposes directions for future research. For instance, underexplored regions or interdisciplinary approaches could enrich the field.

In summary, the study’s novelty lies in its comprehensive bibliometric approach to sustainable finance with a particular lens on “connectivity”—both the interconnectedness of ideas in the literature and the spillover of risks in financial markets. By bridging the fragmented literature and highlighting how different strands of research converge, the study contributes a timely overview that can inform scholars, practitioners, and policymakers alike. The insights from this analysis are intended to support the development of a more resilient and inclusive financial system aligned with sustainability goals, echoing calls in policy circles for evidence-based approaches to climate-aligned finance.

2. Literature Review

Research in sustainable finance encompasses a broad array of topics and has proliferated across disciplines. Here, we briefly review three salient streams of the literature to position our study in context: (i) sustainable finance and firm performance, (ii) green financial markets and instruments, and (iii) bibliometric analyses in finance and ESG.

2.1. Sustainable Finance and Firm Performance

One major branch of work examines how ESG factors influence corporate financial performance and risk. A comprehensive review by Gillan et al. (2021) in the Journal of Corporate Finance finds that integrating ESG and corporate social responsibility (CSR) considerations can potentially mitigate certain risks and enhance firm value, but results vary across contexts. Recent studies delve into specific governance mechanisms. For instance, Liu (2024) analyzes how CSR-linked executive compensation, sustainability committees, and transparency in disclosure drive improvements in firms’ environmental performance (Liu, 2024). Such findings underline that sustainable finance is not merely about new asset classes but also about changing corporate behavior and incentives towards sustainability. However, these firm-level studies often note a gap in understanding systemic implications: while companies may benefit from better ESG practices, it remains unclear how these translate to reduced systemic risk or greater financial stability at the market level. This gap motivates us to look at sustainable finance from a macro and network perspective, as we conduct this bibliometric study.

2.2. Green Financial Markets and Instruments

Another rich stream focuses on specific markets, such as green bonds, renewable energy investments, carbon trading, and impact investing. Green bonds have attracted particular attention as a tool for financing climate-friendly projects. Empirical research indicates that green bonds behave differently from conventional bonds under certain conditions. For example, they may serve as a hedge against oil price shocks or exhibit safe-haven characteristics during times of energy market uncertainty (Mokni et al., 2022). Studies in the Journal of Banking and Finance and other finance journals have documented how investor demand for green assets has grown, especially after events like the Paris Agreement in 2015 that spurred confidence in low-carbon investments (Broadstock et al., 2021). Similarly, research on renewable energy finance (e.g., project financing for wind or solar) highlights unique risk-return profiles and policy dependencies of these assets (Elie et al., 2021; Saeed et al., 2021). A bibliometric review by (Bhatnagar & Sharma, 2022) traces the evolution of the green finance literature, showing how topics like renewable energy, climate policy, and sustainable investing became more prominent over the past decade as the global sustainability agenda accelerated. Nonetheless, these topical studies often operate in silos—green bond scholars may not cross-cite those in, say, sustainable banking or carbon finance—suggesting that the overall connectedness of sustainable finance knowledge is not fully mapped in the existing literature.

2.3. Bibliometric Analyses in Finance and ESG

Methodologically, our work aligns with a growing use of bibliometric analysis to synthesize academic domains. Bibliometric reviews in finance have been used to reveal trends in subfields (Donthu et al., 2021; A. Khan et al., 2022; F. Khan et al., 2022) and to guide future research by identifying influential works. In the context of ESG and sustainability, bibliometric studies have started to appear. For example, (Daugaard, 2020) systematically reviewed ESG investment research and identified emerging themes such as climate risk and shareholder engagement. (De Giuli et al., 2024) combined systematic and bibliometric methods to examine what is known about ESG and financial risk, highlighting that while many papers address ESG’s impact on individual firm risk, few connect these insights to broader financial system stability. Another recent effort by (De Falco et al., 2024) analyzed 903 ESG-related articles and found four thematic clusters (impacts of ESG disclosure, sustainability strategies, accounting/reporting, and responsible investment). Their work offers a high-level thematic map of ESG research, reinforcing that sustainability issues span multiple traditional disciplines and require integration. However, the bibliometric approach has not yet been fully applied to sustainable finance with an emphasis on how the literature itself reflects notions of connectedness, spillover, and systemic risk. Our review distinguishes itself by zeroing in on these aspects, essentially treating the corpus of the sustainable finance literature as a networked system and decoding its dynamics through bibliometric tools. In light of the above, our study contributes to all three streams: we aggregate firm-level and instrument-level insights under one umbrella, and we extend bibliometric research by providing the first extensive mapping of sustainable finance’s intellectual connectivity. By doing so, we respond to calls in the literature for a more integrated perspective on sustainable finance (Cunha et al., 2021; Naeem et al., 2022). The next section details the data and methods used to carry out this analysis.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.1.1. Step 1: Sample Selection

A crucial component of any bibliometric analysis is the citation data. Given that its database recognizes prominent journals from 1985, we seek to collect citation data from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS). Using appropriate keywords, we employ a two-step procedure to retrieve the data from the relevant literature (Chiaramonte et al., 2023; Mbarki et al., 2023). We use extremely general terms in the first stage, which explains how different green finance instruments are related to one another. For this purpose, we conducted a title search using the keywords “ESG” or “green stocks” and “connectedness” or “spillover” or “contagion”, resulting in a total of 198 articles. Next, we use the VOS viewer to analyze the keyword and identify the most relevant alternatives that can aid in understanding the literature on the interconnection of green finance instruments. For the second stage, we employ a more extensive range of the following keywords (“ESG” OR “Green finance” OR “Green stocks” OR “Green bonds” OR “Green energy” OR “Alternative energy” OR “Renewable energy” OR “Green innovations” OR “Green electricity” OR “Environmental social and governance” OR “Green technology” OR “Green transportation” OR “Socially responsible stocks” OR “Clean energy” OR “Sustainable investing” OR “Sustainable stocks” OR “Clean energy stock” OR “Sustainable finance” OR “Climate finance” OR “Environment-related stocks”) AND (“connectedness” OR “spillover” OR “Contagion” OR “co-movement” OR “comovement” OR “Interdependence” OR “Risk transmission”) and perform a search for the specified keywords in all fields. A total of 1891 articles (published through 1 May 2024) were produced by this experiment.

3.1.2. Step 2: Data Refining

A systematic filtering process was conducted to ensure the quality and relevance of the bibliometric dataset. The initial search yielded a total of 1891 documents. To focus on scholarly and peer-reviewed research, the document types were restricted to include only journal articles, early access publications, and review articles, reducing the total to 1833 documents and eliminating 58 items. Subsequently, the dataset was refined by limiting it to specific research areas relevant to the scope of sustainable finance and development. These areas included business economics, environmental science and ecology, public and occupational health, energy and fuels, engineering, public administration, operations research and management science, social sciences, law and government, transportation, and sociology. This step excluded 236 additional documents, bringing the count to 1597. To maintain the integrity of the high-impact literature, only documents indexed in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-E) were retained, resulting in a further reduction to 1489 entries. Non-English publications were then excluded, eliminating one record and narrowing the dataset to 1488. To align the analysis with global policy priorities, only publications that addressed one or more of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were retained, which led to the removal of 227 more items and a refined total of 1261 documents. Lastly, a time filter was applied to include studies published between 1994 and 1 May 2024. As all remaining documents already fell within this range, no additional exclusions were necessary at this stage.

Table 1 summarizes the Data Cleaning Process.

Table 1.

Data Cleaning Process.

The time span was set from 1994 through 1 May 2024. The starting point (1994) roughly corresponds to early discussions of sustainability in finance following the 1992 Earth Summit and the establishment of concepts like “triple bottom line” in the mid-1990s. Extending to 2024 allows inclusion of the most recent developments and trends. We then carefully reviewed the titles and abstracts to ensure each article was indeed within the scope of sustainable finance (excluding, for instance, papers that used the term “sustainable” in a different context). Finally, we use the 1261 articles comprising the period from 1994 to 1 May 2024 for bibliometric analysis. This forms the basis of our bibliometric analysis. These 1261 publications come from 228 different journals and collectively reference over 48,000 distinct sources, indicating a rich and extensive knowledge base. The dataset includes both empirical and theoretical works and features an average of ~3.6 authors per paper, reflecting a moderate level of collaboration across studies.

3.2. Methodology

This study employs quantitative citation analysis to provide a macroscopic overview of the connectedness of sustainable finance research trends and a microscopic examination of thematic content. The chosen methods—citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, co-citation analysis, and trend cartography—are widely recognized in bibliometric research for their robustness in identifying intellectual structures and research networks within scholarly fields (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; Bahoo et al., 2020; Boyack & Klavans, 2010; Naeem et al., 2022).

3.2.1. Citation Analysis

Citation analysis provides a baseline map of influence and was used to answer which works and contributors are most foundational in sustainable finance research. To determine the most influential publications, authors, institutions, and countries, we conducted a citation analysis. This method calculates citation counts and other bibliometric indicators (such as h-index and g-index) to assess the academic impact of publications (Bar-Ilan, 2008; Borgohain et al., 2023; Egghe, 2008). High citation counts were used as proxies for impact, while h-index and g-index metrics were utilized to identify authors and journals that have made sustained contributions to the sustainable finance literature (Ayaz & Zahid, 2024; A. Khan et al., 2022; Naeem et al., 2022). This analysis enables the identification of seminal works and key contributors to the field, helping outline the intellectual framework of the connectedness of sustainable finance research.

3.2.2. Co-Citation Analysis

Co-citation analysis examines the frequency of simultaneous citations of two articles. Identifying intellectual relationships and thematic clusters within the literature (Boyack & Klavans, 2010). Co-citation analysis examines how often pairs of documents are cited together by later papers. If two articles are frequently co-cited, it suggests they share related content or are perceived as jointly important to a topic. For our co-citation network, we applied a citation threshold of 50, allowing us to highlight the most frequently referenced authors and their relationships. This analysis reveals dominant theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches in sustainable finance, with clusters representing focused areas such as green investment risk assessment, ESG metrics, and regulatory impacts on sustainable finance. The summary of this method is as follows:

- Definition: co-citation occurs when two papers are cited together by a third paper.

- Perspective: Forward-looking—it looks at how other researchers group papers together.

- Example: Paper C cites both Paper A and Paper; therefore, Paper A and Paper B are co-cited.

- Implication: These papers are perceived as related by others and might be addressing similar topics.

3.2.3. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis

Bibliographic coupling identifies articles that cite common sources, offering insights into thematic connections and research clusters. In contrast to co-citation (which links papers via shared references), bibliographic coupling links two papers when they cite a common set of references. This technique is useful to identify current research clusters and collaborations, as it groups contemporary papers that draw upon similar prior work. Bibliographic coupling tends to highlight emerging or active research fronts because authors working on similar problems will cite overlapping bodies of literature. This method reveals the evolution of subfields within sustainable finance by linking works that share references, thus identifying active research fronts and collaborative patterns (Boyack & Klavans, 2010; A. Khan et al., 2022; van Eck & Waltman, 2010). For our analysis, a minimum threshold of five citations per document was applied, allowing us to capture well-established research areas while ensuring a representative sample. The summary of this method is as follows:

- Definition: bibliographic coupling occurs when two papers cite the same third paper(s) in their reference lists.

- Perspective: Backward-looking—it focuses on shared references.

- Example: Paper A and Paper B both cite Paper X; therefore, Paper A and Paper B are bibliographically coupled.

- Implication: These papers may be related because they build upon or are influenced by the same prior work.

3.2.4. Trend Cartography and Keyword Analysis

Trend cartography and keyword co-occurrence analysis were used to map the growth trajectories of specific topics and to identify emerging research areas. Using VOSviewer and the Biblioshiny package of the R and RStudio software (R version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14 ucrt)) and RStudio (2024.12.1+563.), we visualized thematic clusters and tracked their temporal evolution, revealing shifts in research focus over time (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; van Eck & Waltman, 2010). A keyword co-occurrence threshold of five was set, resulting in the identification of 178 key terms that characterize current research interests in sustainable finance, including “green bonds”, “renewable energy”, “connectedness”, and “systemic risk” (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

3.2.5. Collaboration Network Analysis

The collaboration network of authors in sustainable finance provides insight into the interconnectedness of researchers, institutions, and countries contributing to this field. The collaboration network of authors, institutions, and countries provides a comprehensive view of the structure and dynamics of sustainable finance research. The analysis of author collaborations highlights the importance of interdisciplinary efforts, with key researchers acting as central connectors between different research domains. Additionally, the study of institutional and country-level collaborations emphasizes the global and interconnected nature of sustainable finance, where research outcomes are shaped by contributions from diverse geographical and institutional actors. This network analysis is essential for identifying research gaps, opportunities for collaboration, and the key players driving the future direction of sustainable finance research. Understanding these connections can guide future policy, research, and investment strategies in a field that is increasingly pivotal in addressing global sustainability challenges.

3.3. Analytical Tools

The data visualization and network analyses were conducted using VOSviewer, Biblioshiny (an extension of the Bibliometrix package), and RStudio. VOSviewer was employed for bibliographic coupling and co-citation mapping due to its robust capabilities in visualizing large bibliometric datasets and its established use in scholarly network analysis (Bahoo et al., 2020; Chiaramonte et al., 2023; A. Khan et al., 2022; Mbarki et al., 2023; van Eck & Waltman, 2010). Biblioshiny and Bibliometrix offer comprehensive tools for descriptive and inferential analysis, enabling us to conduct keyword analyses, trend cartography, and time-series visualizations of publication growth in sustainable finance (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017). Together, these tools facilitated a multi-dimensional analysis, allowing for an in-depth exploration of the literature landscape.

4. Results

4.1. Features of Data Sample

Table 2 displays the citation data features of 1261 publications, published between 1994 and 1 May 2024, with an annual growth rate of 16.14%. These articles were obtained from 228 different sources, with 1154 research articles and 25 paper reviews. The mean citations per document is 28.02, whereas the document mean age is 2.71. A total of 3540 authors have contributed to these publications, which have utilized 48,471 references and 3469 keywords. There are 75 documents with a single author, and an average of 3.59 co-authors per document, indicating an international co-authorship rate of 37.99%. This demonstrates the robust collaboration among scholars in the field of sustainable finance research.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics.

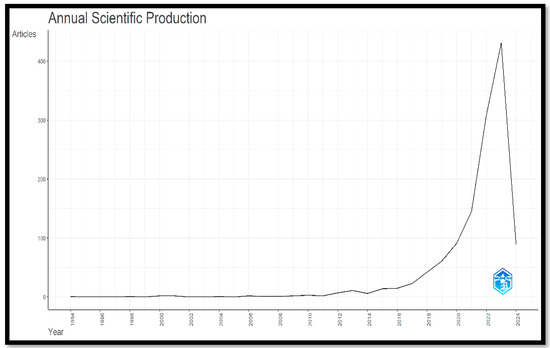

4.2. Annual Scientific Output

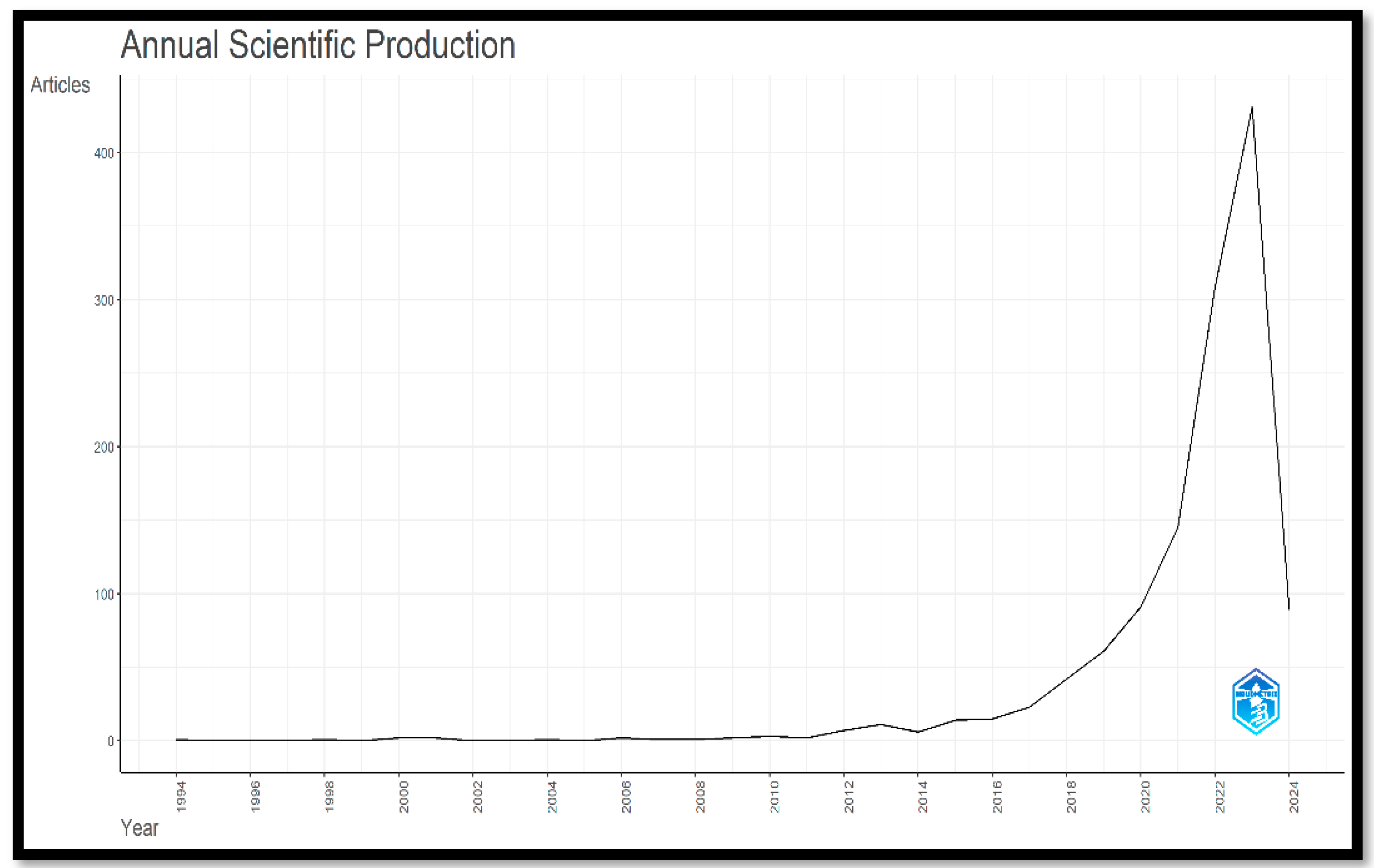

Figure 1 displays the yearly scientific output in sustainable finance, revealing that the initial years did not prioritize ESG principles in investment until the early 1990s, which signifies the commencement of research in this area, with just a small number of articles being published. The world has begun implementing sustainable strategies in various aspects of human life because of the growing curiosity of academicians and scholars in sustainability and global warming issues, the depletion of natural resources, greenhouse gas emissions, clean energy, the environment, and the issuance of green bonds. Figure 1 illustrates the production trends from 1994 to 2024. During the period from 1990 to 2014, a total of 42 articles were published, which accounted for barely 3% of the whole production. Simultaneously, 97% (1219) of publications were published in the decade prior to 2015–2024. A total of 89 articles will be generated throughout the initial four months of 2024. The production trend for sustainable finance is seeing exponential growth, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Annual Scientific Production.

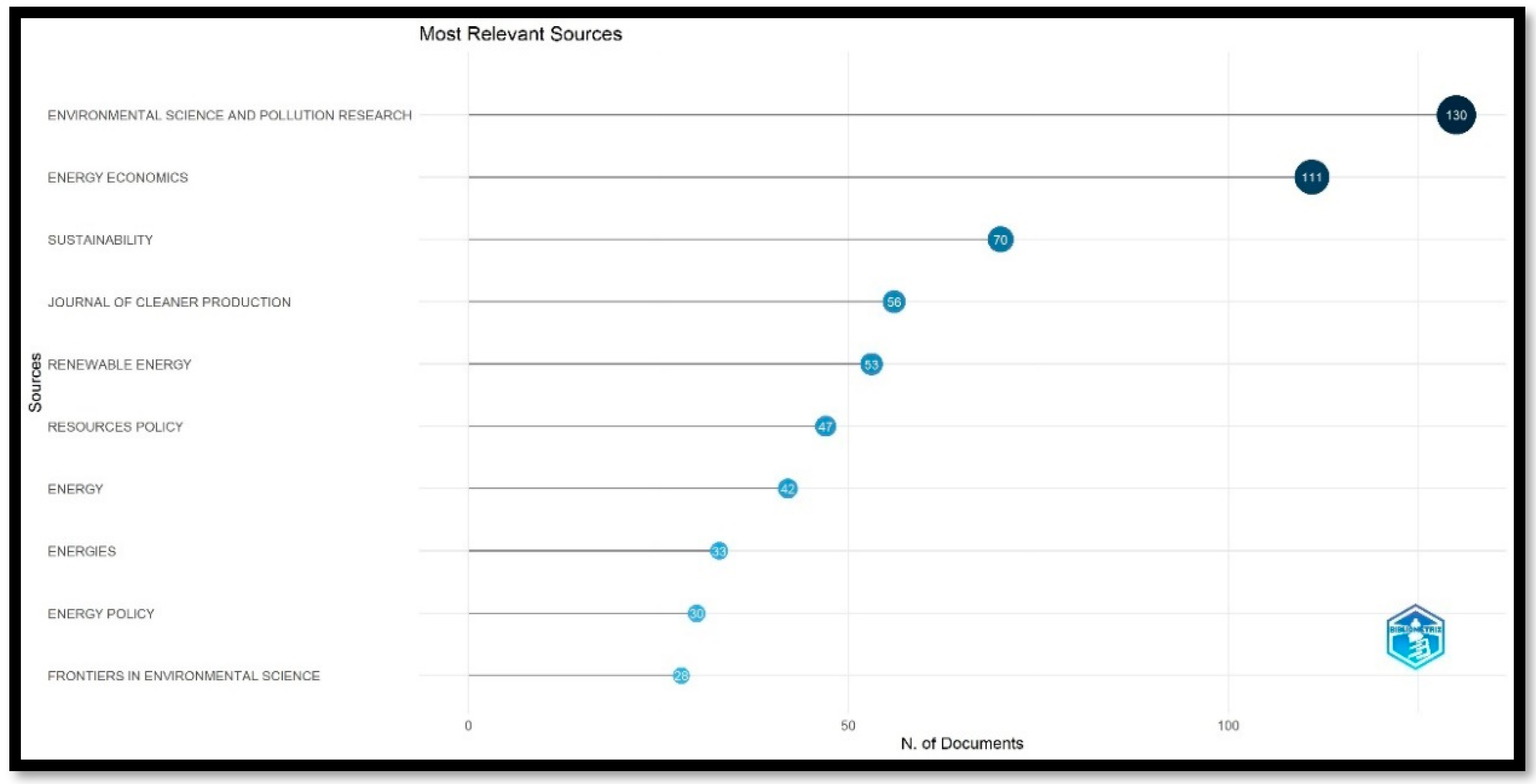

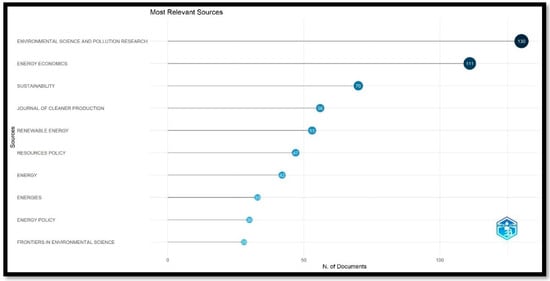

4.3. Most Significant Sources

Sources are essential for the advancement of a research stream. Table 3 and Figure 2 rank the top 12 sources according to their total publication count. Journal quality can be assessed through metrics including citation counts and the h-index. The importance of a research article is assessed by the citations it garners from scholars. The h-index represents the highest quantity of scientific papers that have garnered the most citations (Egghe, 2008). The G-index quantifies the maximum number (n) of publications that have garnered a minimum of n2 citations (Nalubega & Evans, 2015). The M-index serves as an alternative designation for the h-index. The text presents the h-index for each year, commencing from the initial year of publication (Egghe, 2008). Environmental Science and Pollution Research holds the top position with 130 publications and 1849 citations. An intriguing observation is that it commenced publication in this domain in 2019 and has consistently maintained the top position. Energy Economics began publication in 2003 and has published a total of 111 pieces, currently ranking second. Despite this, Energy Economics maintains a significant h-index, having garnered 4886 citations and ranking first. Sustainability is the third-ranked journal with 70 publications and has been publishing in this domain since 2016, receiving 821 citations. The Journal of Cleaner Production has published a total of 56 pieces. Nevertheless, the h-index of this journal is significant and has gathered 2357 citations. Another well-regarded journal is Renewable Energy, having 53 publications and 1637 citations.

Table 3.

Most Influential Sources.

Figure 2.

Most Relevant Sources.

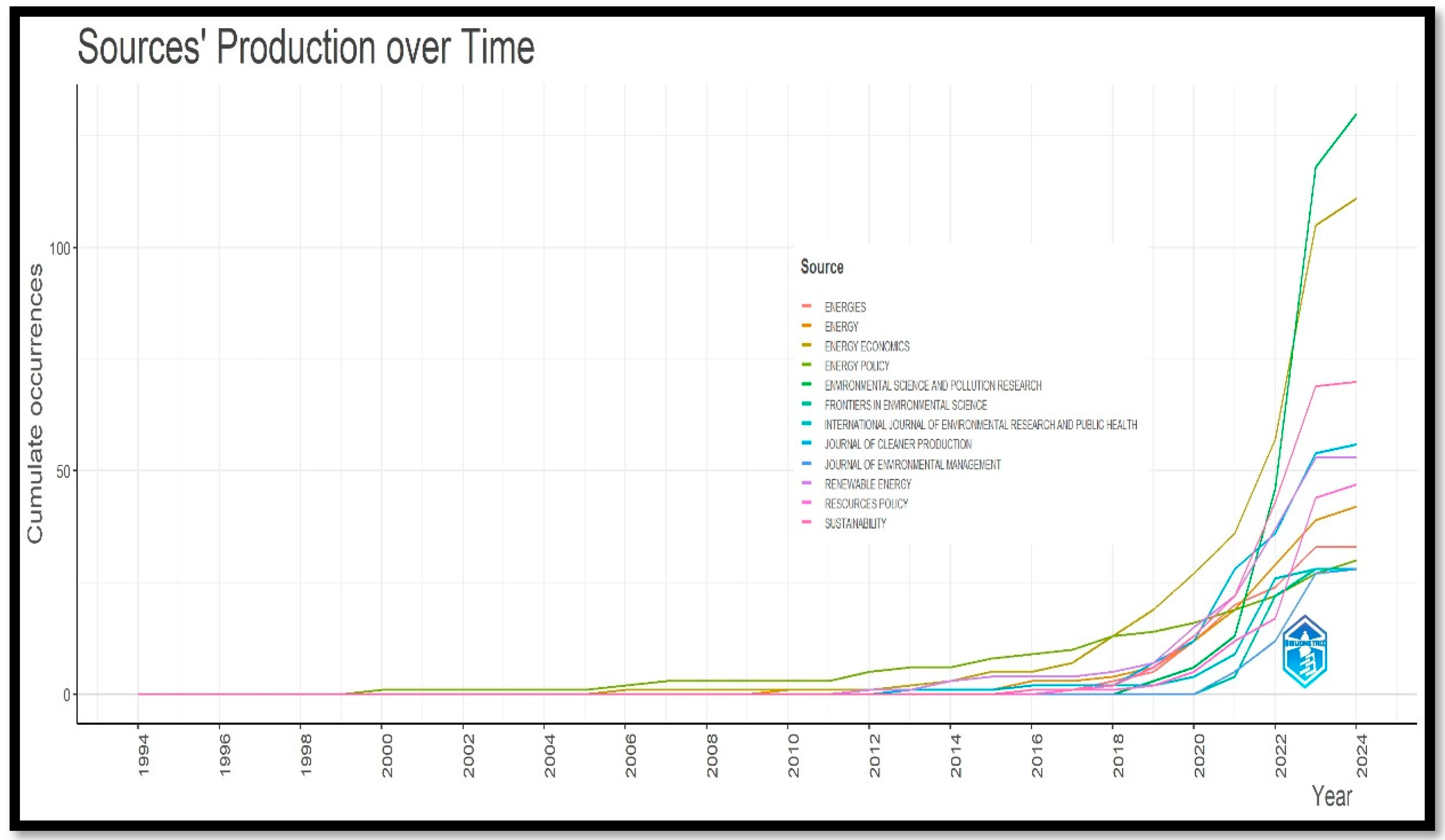

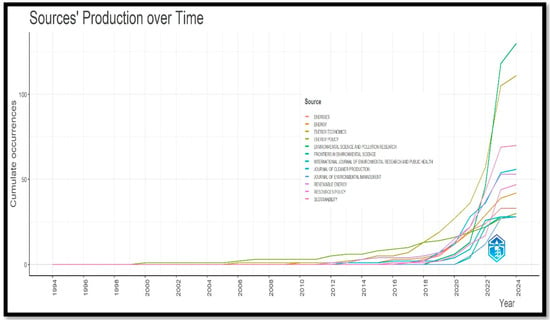

Figure 3 illustrates the increase in the sources, emphasizing that there was not much research conducted on the topic of sustainable financing in the 1990s. The stream gained prominence in early 2014 and experienced significant growth over time. Energy Economics has seen a remarkable increase, while Environmental Science and Pollution Research has consistently published more research papers on green finance. Likewise, the Journal of Cleaner Production and Sustainability is experiencing consistent growth and is expected to continue increasing in the future.

Figure 3.

Sources Production Overtime.

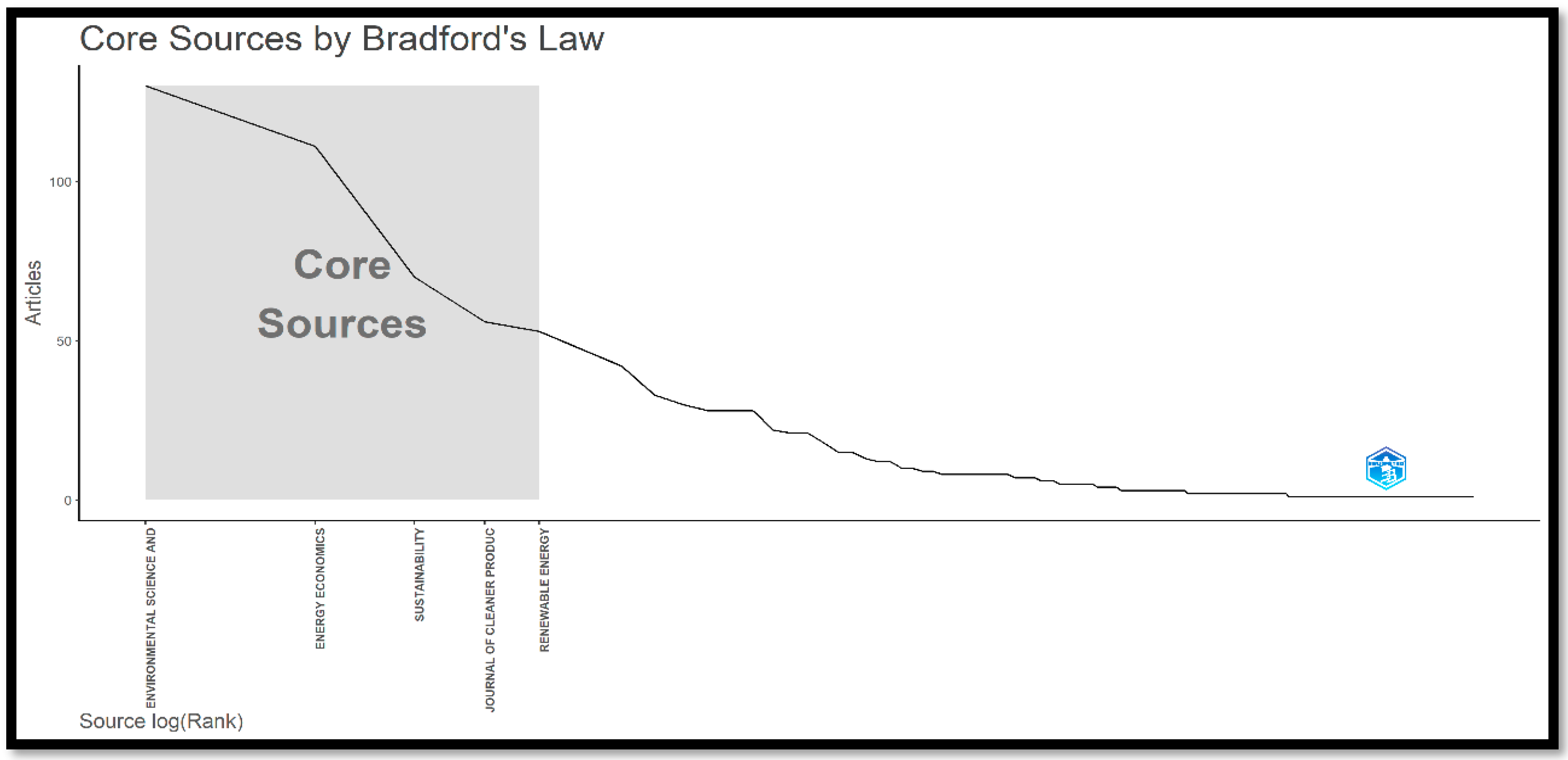

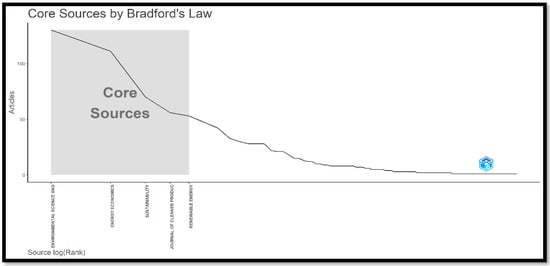

Application of Bradford’s Law

A bibliometric principle, Bradford’s Law, is instrumental in identifying core journals that significantly contribute to a certain field of research. It suggests that a relatively small number of journals will produce the mainstream of relevant research papers on a topic, while the rest will be dispersed across many less prolific sources. This paper applies Bradford’s Law to categorize the most influential journals in sustainable finance and their connectedness, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Core Sources by Bradford’s Law.

The paper identifies core journals such as Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Energy Economics, Sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Renewable Energy, which dominate the literature on sustainable finance connectedness. These journals align with Bradford’s core zone of prolific contributors, as indicated by their high output, citations, and h-index. Beyond this core, secondary and tertiary zones are established, consisting of journals with progressively fewer articles. This analysis underscores the concentration of knowledge in a few leading sources, which aligns with Bradford’s predictions and highlights where researchers should focus on accessing foundational and cutting-edge studies in this field.

4.4. Most Influential Authors

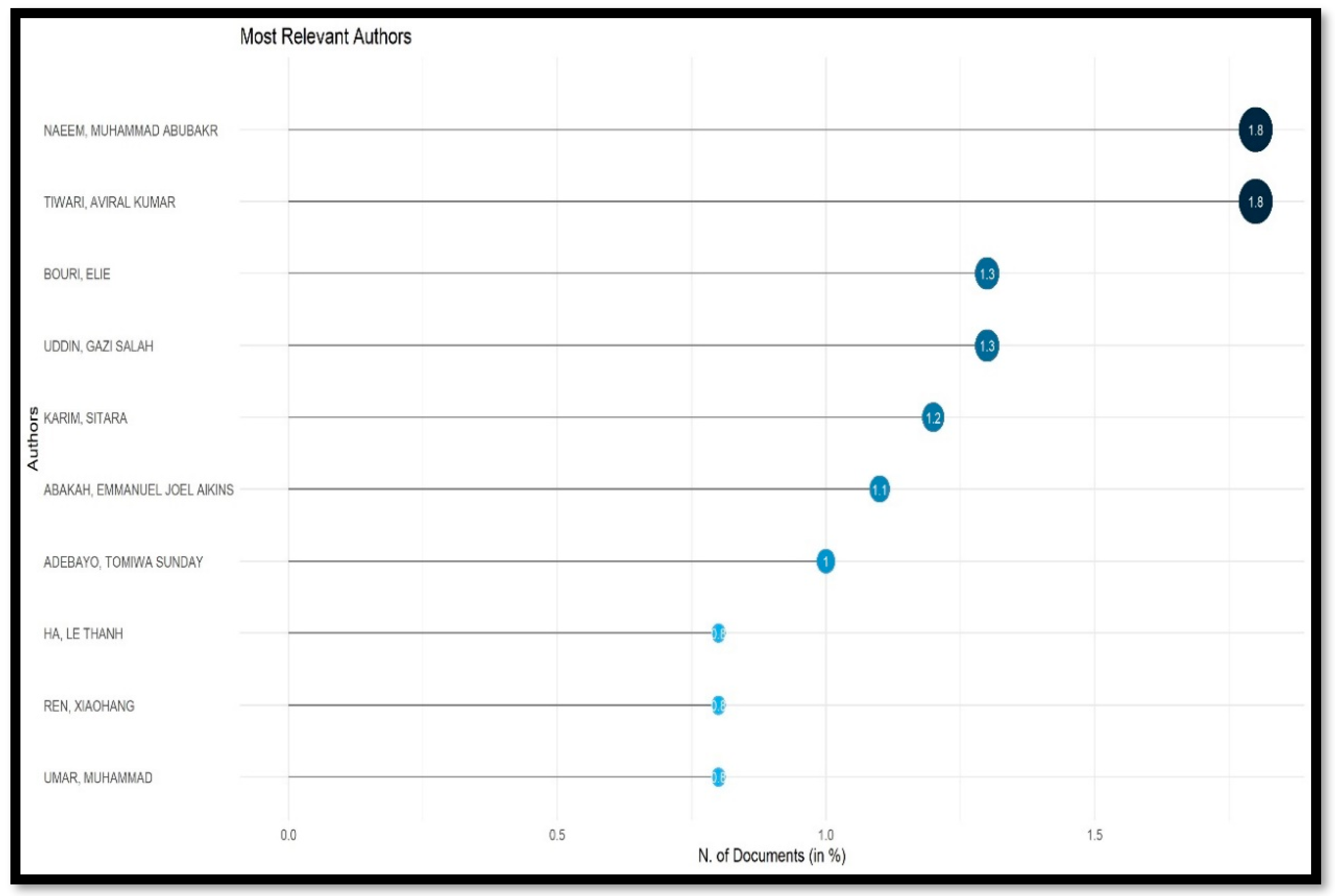

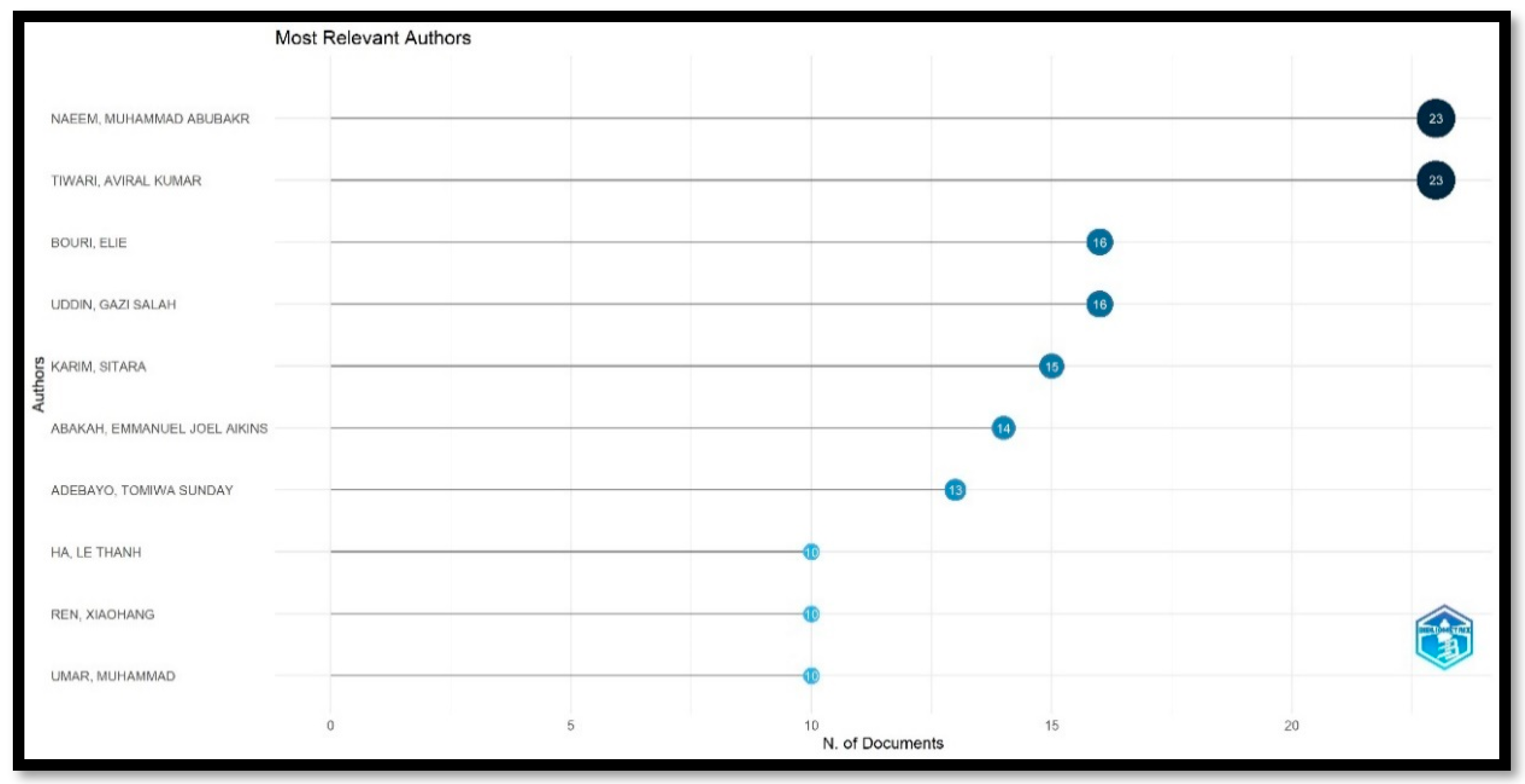

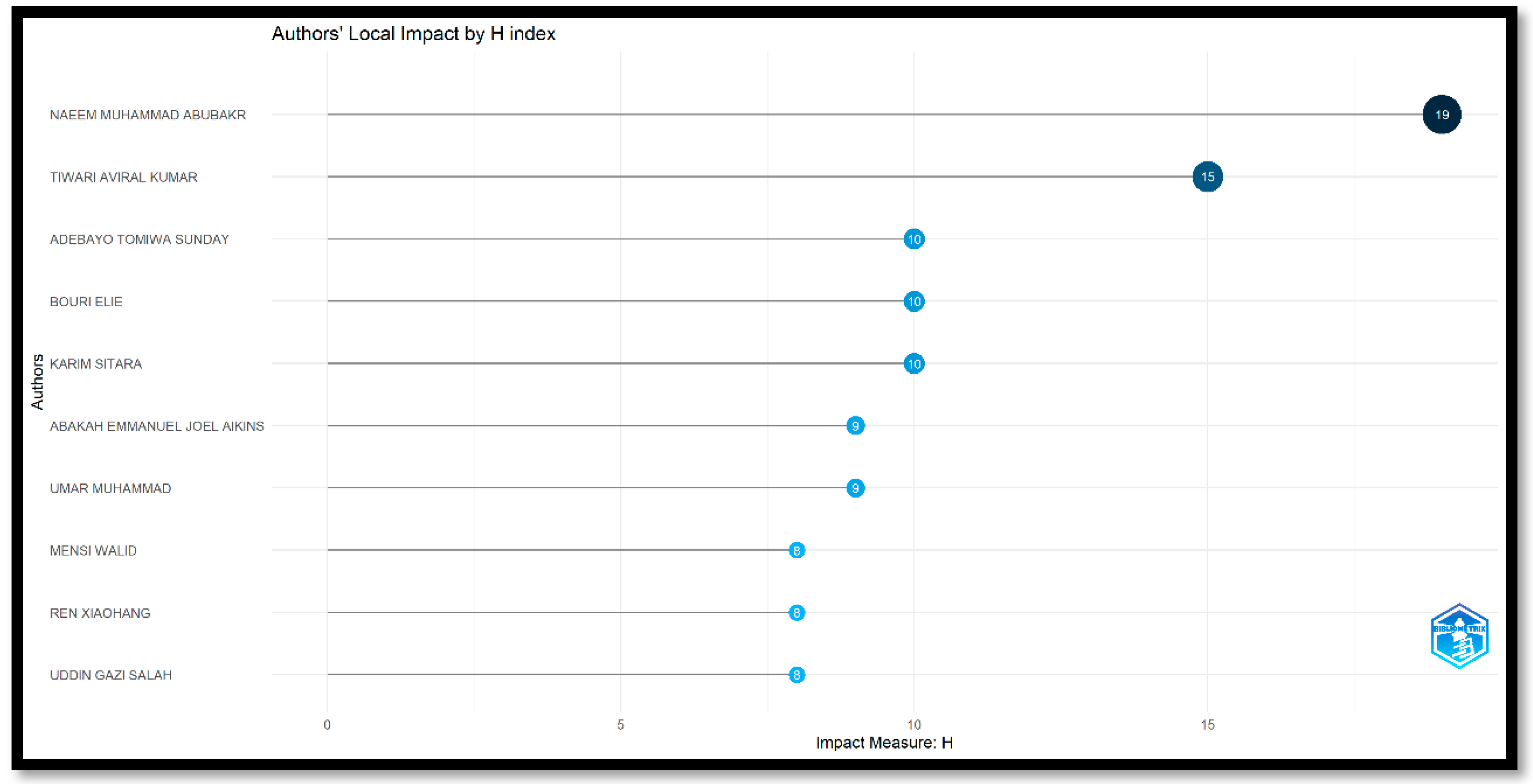

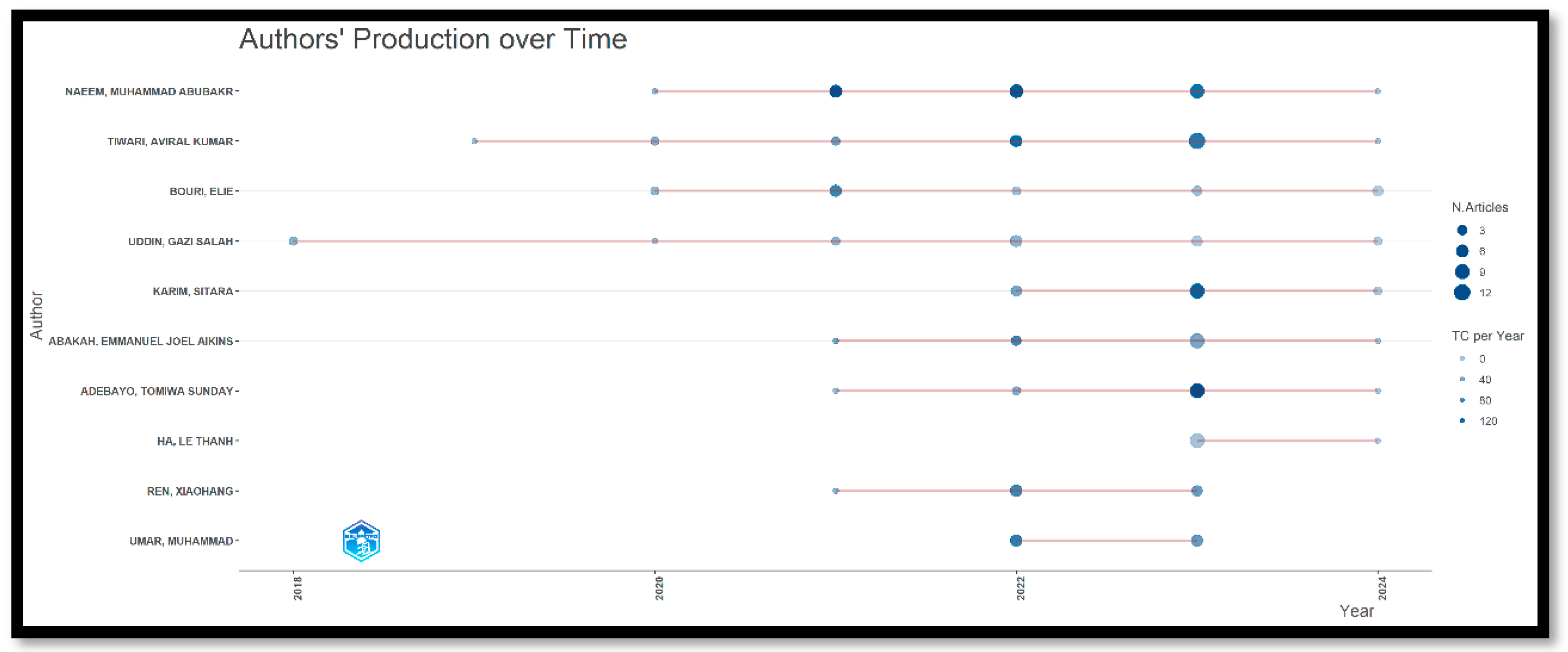

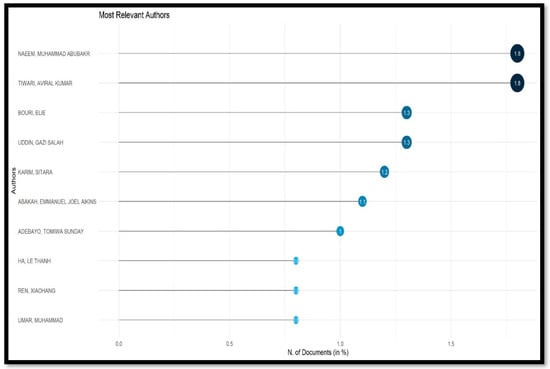

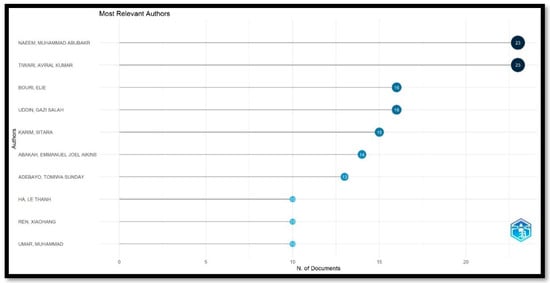

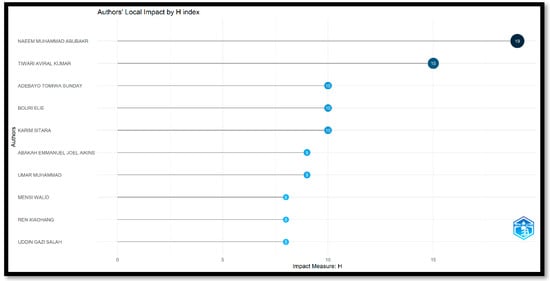

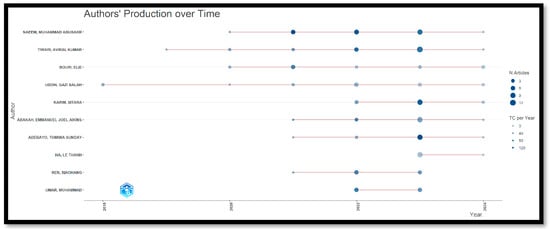

Table 4 and Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 display the prolific authors who are the primary contributors to the field of connectedness in sustainable finance research, and this analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of their total work through factors such as the number of publications they have authored, co-authorship, and citations received. This analysis is derived from the aggregate number of articles authored by an individual. According to Table 4 and Figure 6, Naeem Muhammad Abubakr and Tiwari Aviral Kumar are the leading researchers in the connectedness of sustainable and green finance; they published an equal number of 23 documents, having 1399 and 1080 citations, respectively. Adebayo Tomiwa Sunday, Bouri Elie, and Karim Sitara are in second place with an equal 10 academic contributions, while Abakah Emmanuel Joel Aikins and Umar Muhammad are rated third with nine publications. Figure 6 displays the writers who have published the highest number of works in the field of the connectedness of sustainable finance, indicating their level of activity. The majority of the most prolific authors began their publications in 2019.

Table 4.

Most Influential Authors.

Figure 5.

Most Relevant Authors (No. of Documents in Percentage).

Figure 6.

Most Relevant Authors (No. of Documents).

Figure 7.

Authors’ Local Impact by H index.

Figure 8.

Authors’ Production over time.

4.4.1. Application of Lotka’s Law

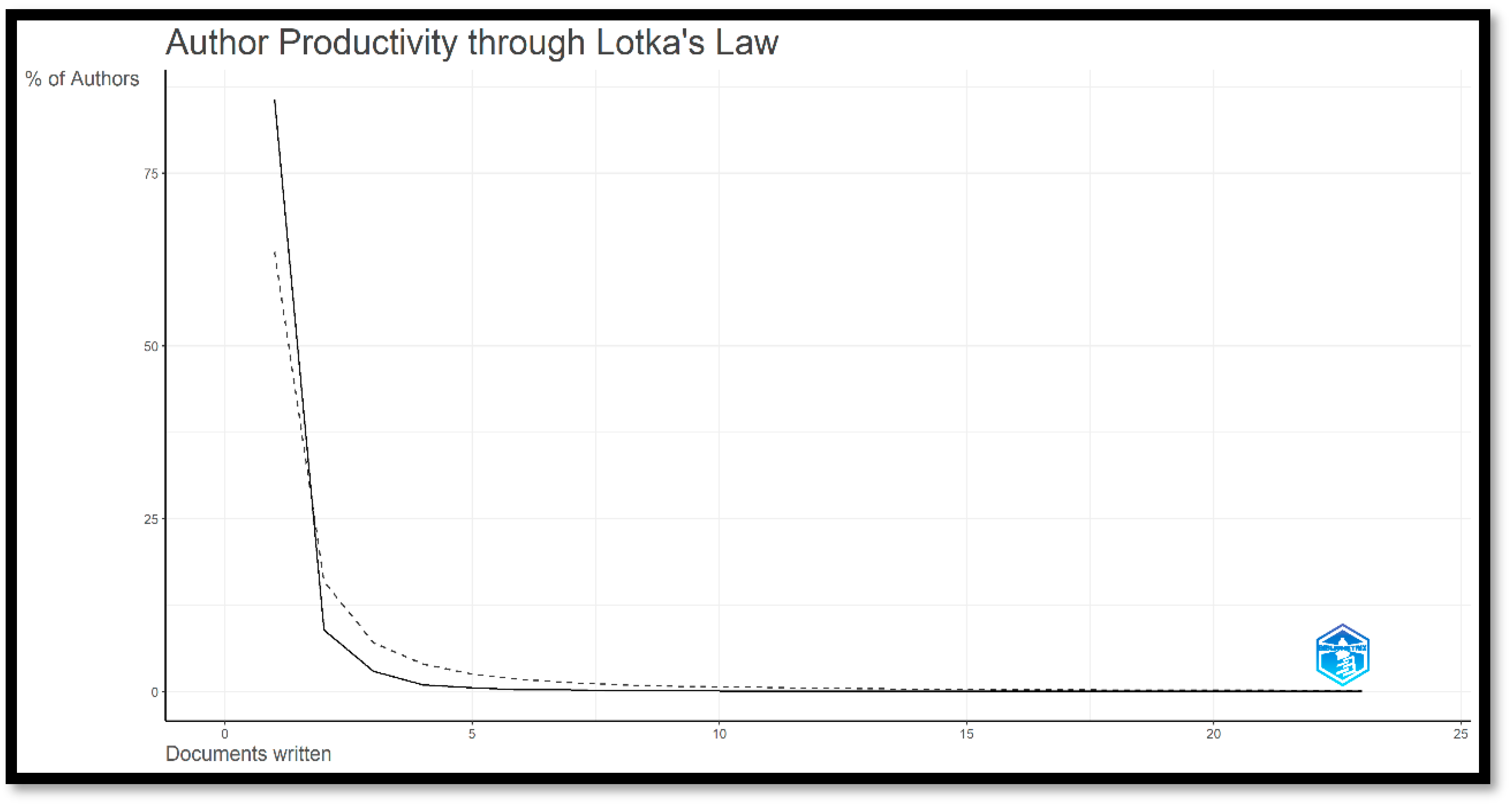

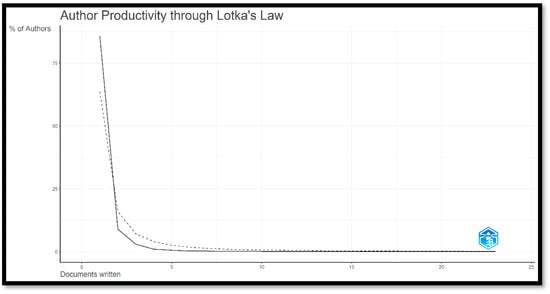

Lotka’s Law is a bibliometric principle that describes the frequency of authorship in a particular scientific field. Specifically, it posits that the number of authors who publish a given number of articles in a field follows the power law distribution. According to Lotka’s Law, the number of authors who produce n articles is inversely proportional to n2, meaning that a small number of authors produce a large number of publications, while a majority of authors contribute only a few works. In the context of this paper, Lotka’s law is applied to analyze the distribution of publications among the authors in the field of connectedness in sustainable finance. The study’s results, particularly the analysis presented in Table 5 and Figure 9, show how authorship in the connectedness of sustainable finance is distributed according to Lotka’s Law. The relevance of Lotka’s Law to this study is significant.

Table 5.

Lotka’s Law.

Figure 9.

Author Productivity through Lotka’s Law.

4.4.2. Uneven Distribution of Authorship

Lotka’s Law suggests that the number of authors producing a given number of articles follows a predictable pattern: a small number of authors publish a large percentage of the articles, and most authors publish only a few. This paper’s analysis of authorship (as shown in Table 5 and Figure 9: Lotka’s Law) demonstrates this very phenomenon. In the field of sustainable finance, a small group of authors, such as Naeem Muhammad Abubakr and Tiwari Aviral Kumar, each with 23 published articles, contribute significantly to the literature. These authors can be regarded as the “high productivity” researchers in the field, representing the “core” of the research community.

4.4.3. Publication Frequency Distribution

As Lotka’s Law predicts, the rest of the authors contribute a disproportionately smaller number of papers. According to the data in the study, many authors have published only a small number of papers (e.g., one to five). This is a typical pattern in most academic fields, where a few prolific authors dominate while the majority have limited output.

4.4.4. Implications for Research Networks

Lotka’s law helps identify how research networks are structured. In this paper, the concentration of research output among a few authors suggests that these individuals are likely the primary contributors to shaping the research agenda in the connected field of sustainable finance. It also underscores the importance of collaborative networks where highly productive authors often influence the direction and growth of the field.

4.4.5. Quantitative Representation

This paper uses quantitative bibliometric data to support this analysis (e.g., citation counts, author counts, and publication numbers), which aligns perfectly with the mathematical model of Lotka’s Law. The distribution of authorship and the citations of their works are consistent with the expected pattern of high productivity among a small group of scholars. The application of Lotka’s Law in this study is appropriate and provides valuable insights into the authorship dynamics within the field of connectedness of sustainable finance. It underscores the concentration of contributions from a small group of highly productive authors and highlights the overall productivity patterns in the field. By acknowledging this law, this paper offers a clearer understanding of the research landscape and how knowledge dissemination is concentrated in a few hands, which can guide future research efforts and collaborations. This distribution offers valuable insights into research productivity and collaboration trends in the field, helping to identify key influencers and contributors who drive the development of the research agenda. In summary, Lotka’s Law highlights the uneven distribution of scholarly output in the field of connectedness in sustainable finance, with a few authors generating a large proportion of publications while the majority of authors produce fewer works. This helps in understanding the structure and dynamics of research activity in the area of connectedness of sustainable finance.

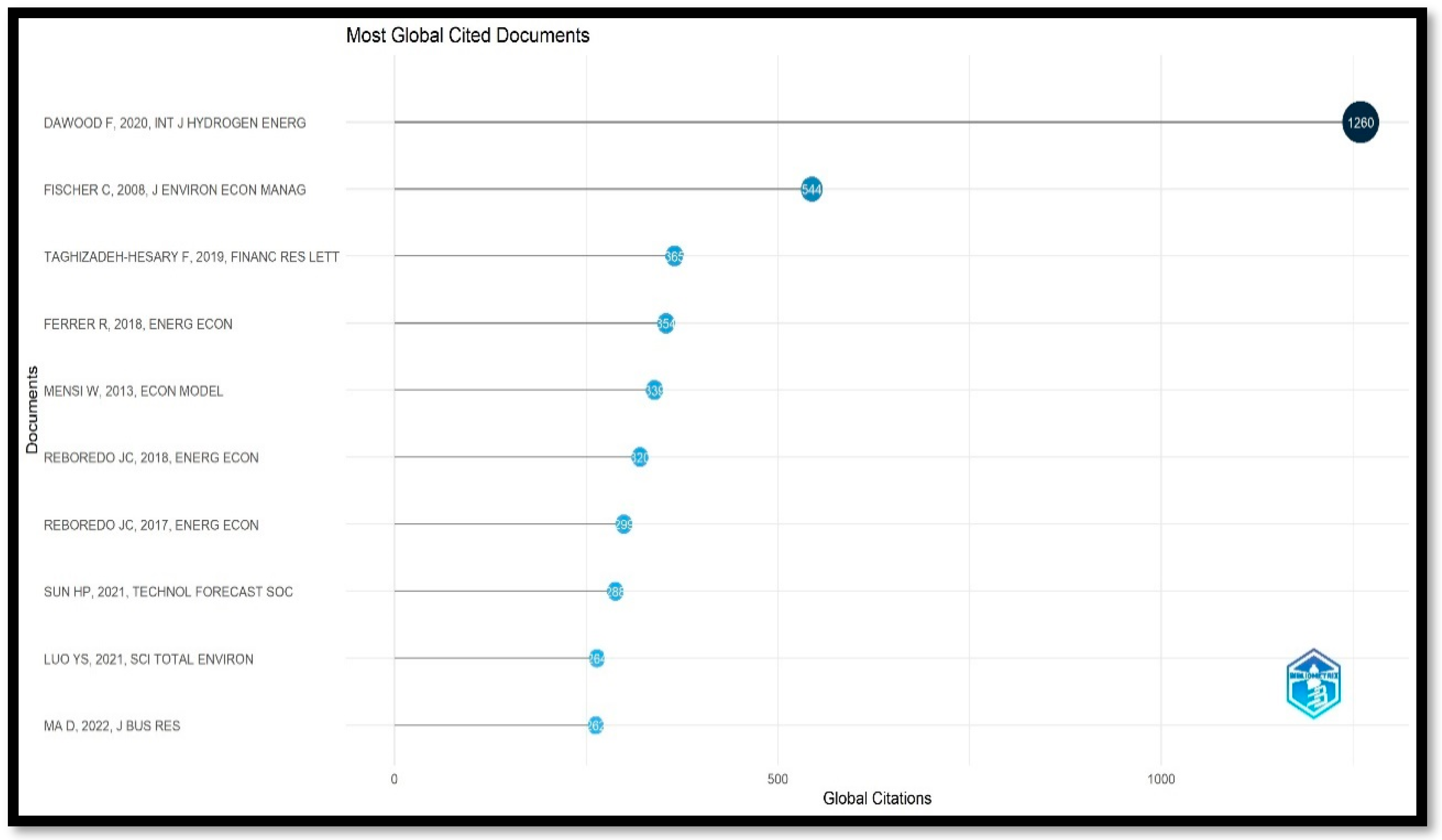

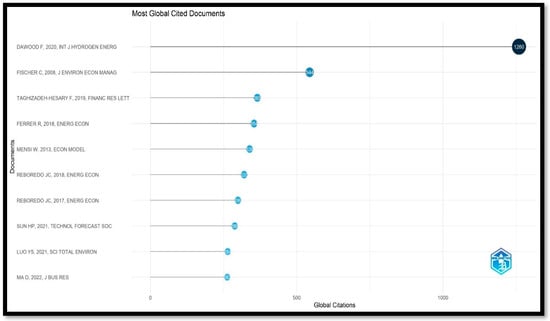

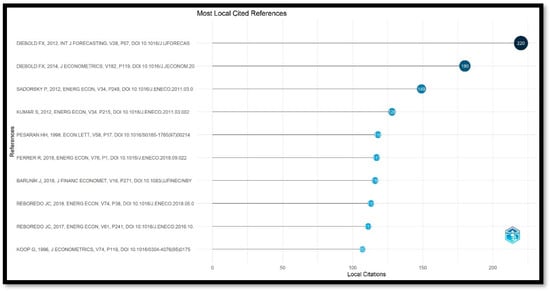

4.5. Most Influential Documents

Most influential documents are widely cited locally and globally. The influential documents demonstrate the continued research and expansion of a specific issue in the study. The top ten most important papers are displayed in Figure 10 and Figure 11. The work “Hydrogen production for energy: An overview” by Dawood F, published in the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy in 2020, has received the most citations, demonstrating its fundamental role in the development of climate change. It is the most influential paper, having 1260 global citations. The research of Fischer and Newell (2008), titled “Environmental and technology policies for climate mitigation”, published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, has the second highest global citations, which is 544. The third paper, having the highest global citations (365), is “The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment”, written by Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2019), published in Finance Research Letters.

Figure 10.

Most Global Cited Documents (Dawood et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2018; Fischer & Newell, 2008; Y. Luo et al., 2021; Ma & Zhu, 2022; Mensi et al., 2013; Reboredo et al., 2017; Reboredo, 2018; Sun et al., 2021; Taghizadeh-Hesary & Yoshino, 2019).

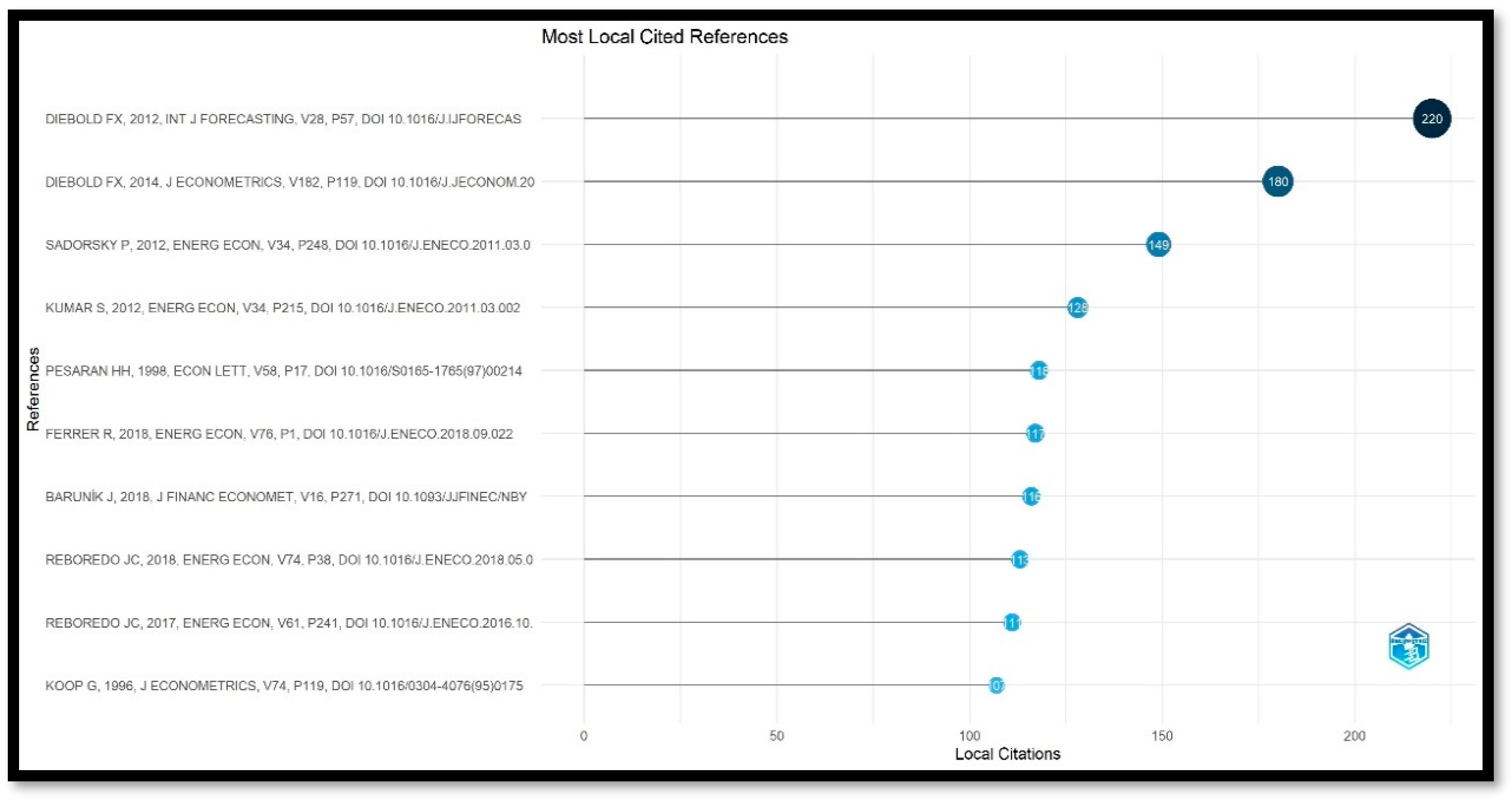

Figure 11.

Most Local Cited References (Baruník & Křehlík, 2018; Diebold & Yilmaz, 2012, 2014; Ferrer et al., 2018; Koop et al., 1996; Kumar et al., 2012; Pesaran & Shin, 1998; Reboredo et al., 2017; Reboredo, 2018; Sadorsky, 2012).

The seminal work in the field of connectedness in sustainable finance by Ferrer et al. (2018). “Time and frequency dynamics of connectedness between renewable energy stocks and crude oil prices” has 354 global citations published in Energy Economics, a prestigious journal. The methodological work for the measurement of connectedness, titled “Better to give than to receive: predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers”, has the most local citations, 220, and “On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms” has local citations of 180, written by Diebold Fx, 2012; 2014, published in the International Journal of Forecasting and Journal of Econometrics, which are dominant papers to the methodology for the spillover and connectedness.

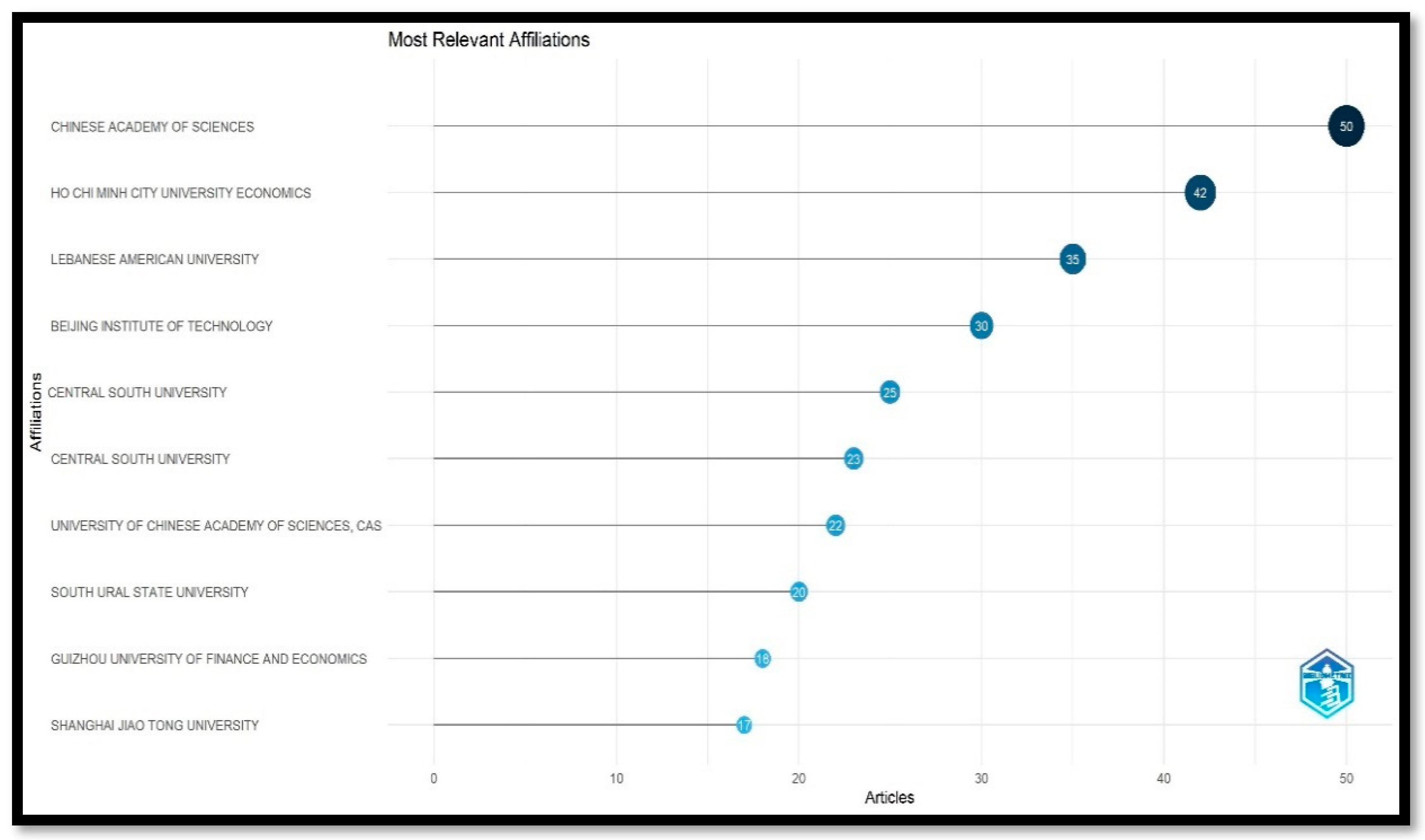

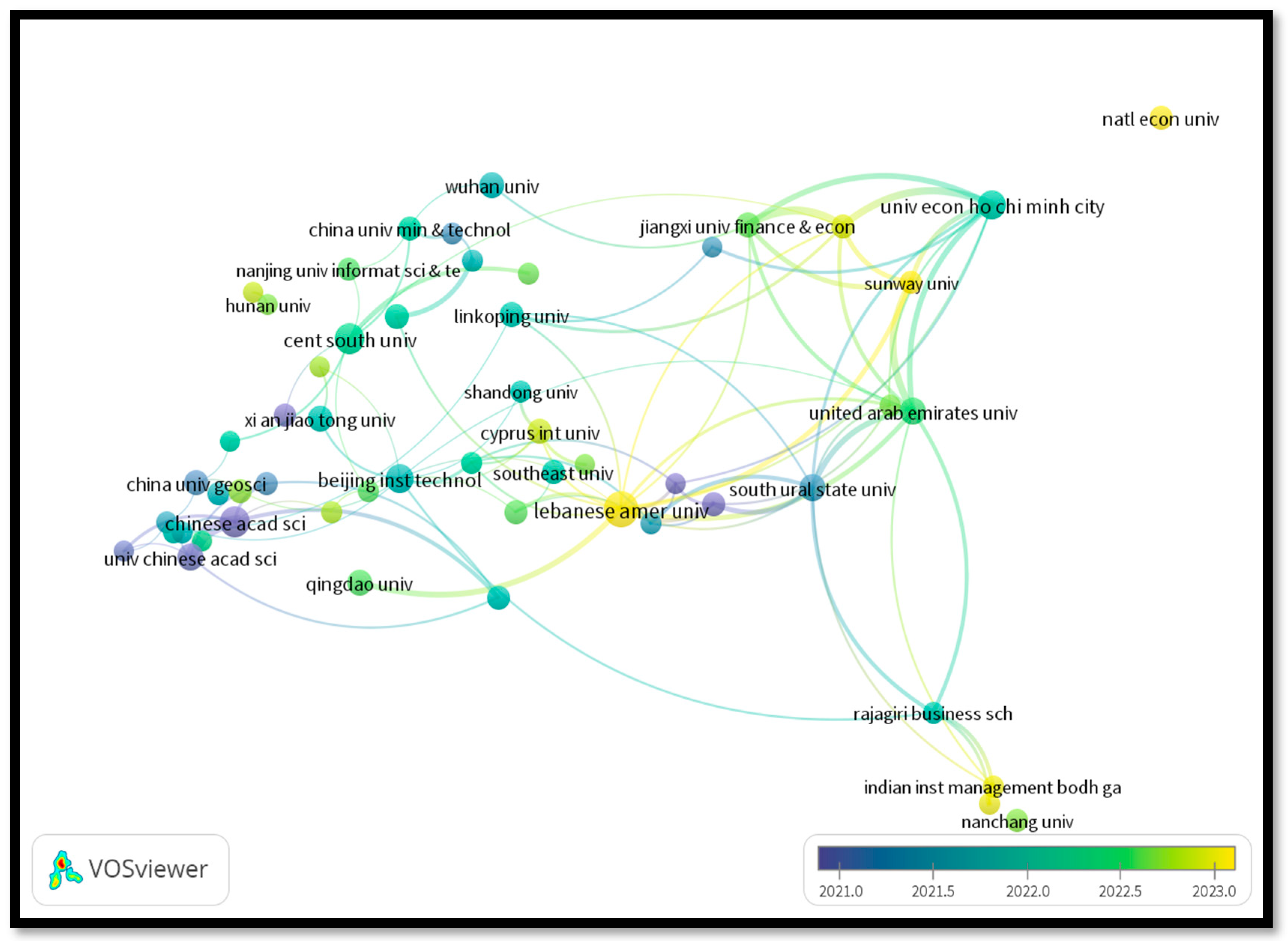

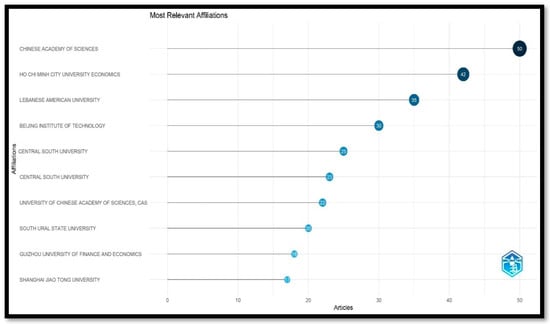

4.6. Most Influential Affiliations

Table 6 and Figure 12 illustrate the ten most influential affiliations in the field of sustainable finance research. The Chinese Academy of Sciences is the most influential institution, with a total of 50 contributions. Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics has published 42 research articles. Lebanese American University contributed 35 articles to the field of sustainable finance spillovers.

Table 6.

Most Influential Affiliations.

Figure 12.

Most Relevant Affiliations.

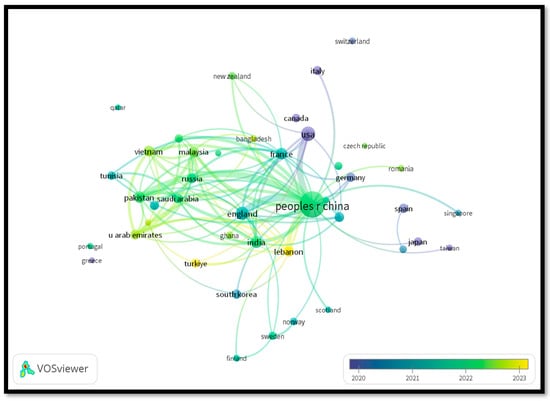

4.7. Most Influential Countries

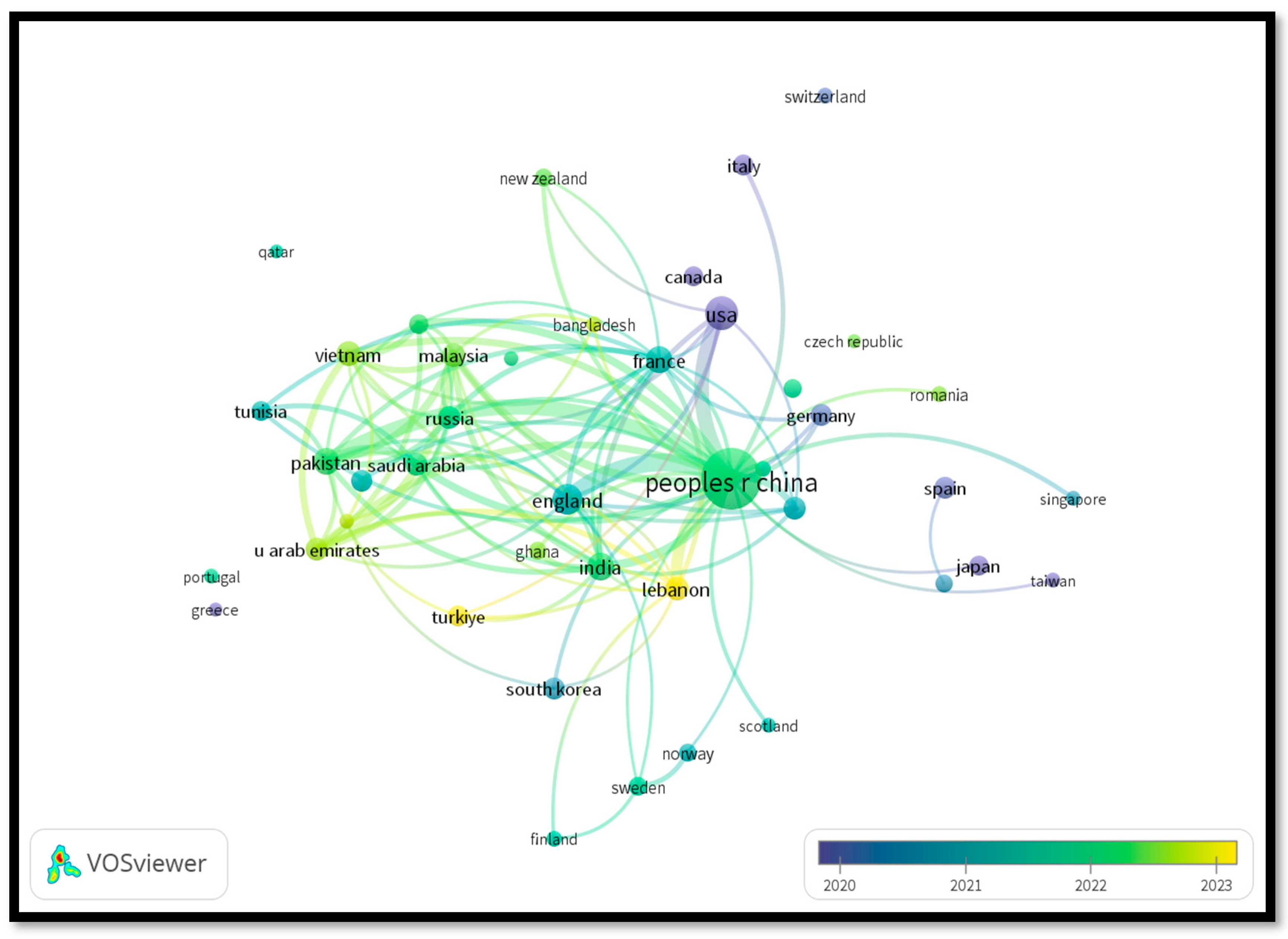

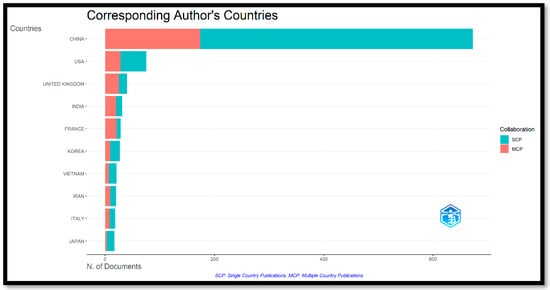

This demonstrates the countries’ contributions to the overall scientific productivity. Table 7 and Figure 13 display the top 10 countries that have made significant contributions to sustainable finance and its connectedness. China is the primary contributor to the field of sustainable finance research, having published 673 articles, accounting for 53.37% of the sample. This indicates China’s strong commitment to addressing climate change concerns. The contributions from other countries comprise 46.37% of the sample, with the USA, UK, India, and France exerting the greatest influence.

Table 7.

Most Influential Countries.

Figure 13.

Corresponding Author’s Countries.

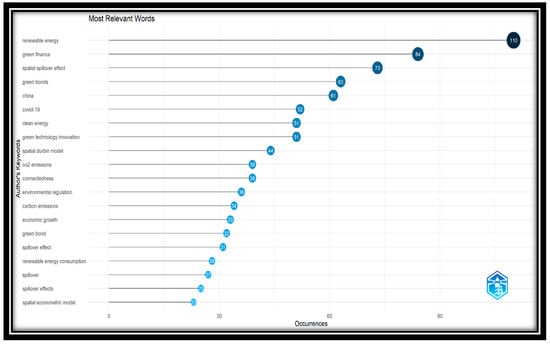

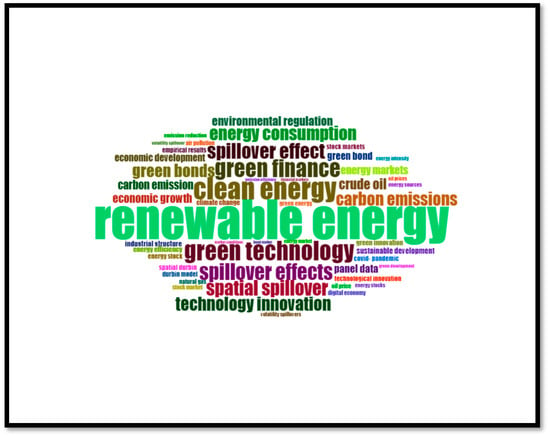

4.8. Most Important Words

The occurrence of words serves as an indicator of the development and subject matter within a certain area of study (Kumar et al., 2021). This report provides valuable insights into the prevailing trends in research popularity. The top 20 most frequently used words by the authors, along with their frequencies, are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Most Relevant Words- Author Keywords.

The most commonly used terminology in the literature on the interconnectedness of sustainable finance is “renewable energy”, “green finance”, “spatial spillover effect”, “green bonds”, “clean energy”, “green technology innovation”, “connectedness”, “spillover effect”, “uncertainty”, “CO2 emissions”, “environmental regulations”, “renewable energy consumption”, and “economic growth”.

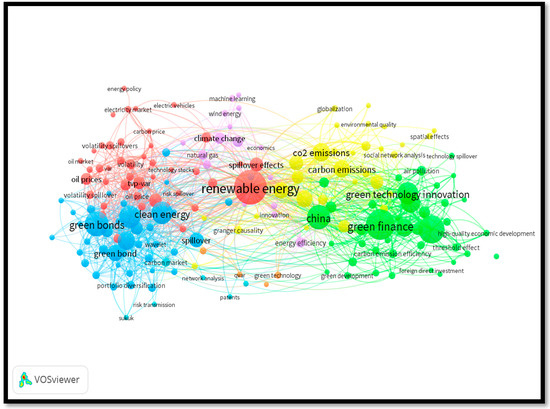

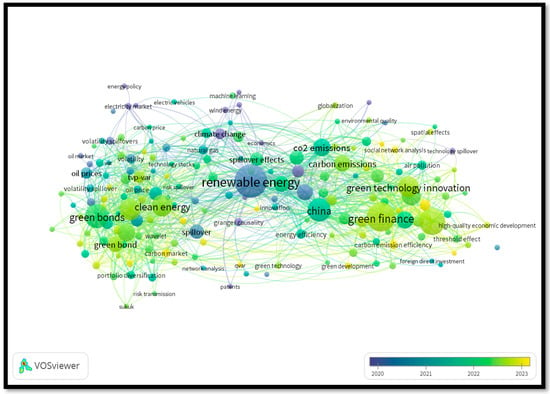

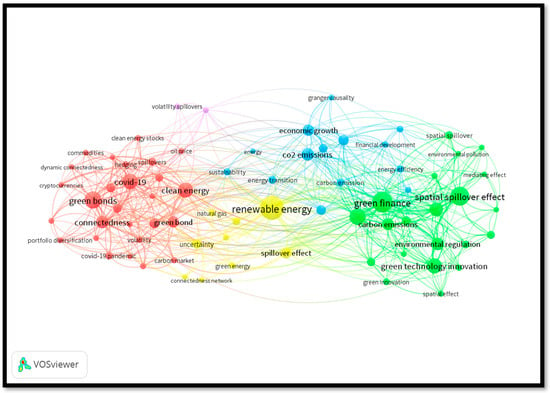

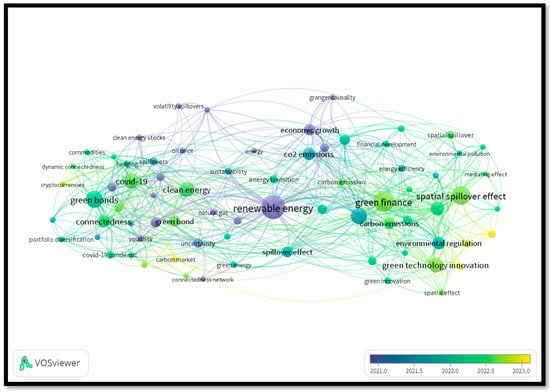

4.9. Co-Occurrence Network of Author Keywords

Figure 15 and Figure 16 display a map that shows the frequency of keywords. Figure 15 presents the results of author keywords that meet the minimum occurrence criterion of 5. Out of a total of 3469 authors’ keywords, only 178 keywords matched the threshold criteria. Figure 16 illustrates this trend in relation to time.

Figure 15.

Co-Occurrence Network—Min-5-178 Keywords.

Figure 16.

Co-Occurrence Network—Min-5-178 Keywords over Time.

Figure 17 and Figure 18 show the network diagram of only the 73 most frequent words that meet the minimum occurrence threshold of 10.

Figure 17.

Co-Occurrence Network—Min-10-73 Keywords.

Figure 18.

Co-Occurrence Network—Min-10-73 Keywords over Time.

Figure 17 shows five distinct clusters of terms. Cluster 1 (red) has 27 keywords, Cluster 2 (green) contains 21 keywords, Cluster 3 (blue) comprises 14 keywords, Cluster 4 (yellow) covers 9 keywords, and Cluster 5 (purple) has only 2 keywords. These clusters represent the prevailing pattern in the connectedness of sustainable financing. These clusters represent several research streams that focus on a specific dimension of connectedness in sustainable finance.

Thematic Clusters and Key Research Themes

Using co-citation and keyword co-occurrence analyses, we extracted the major thematic clusters that define sustainable finance research. We present these themes along with representative topics and insights from each:

Cluster A: Green Bonds and Market Spillovers

This theme (corresponding to the largest red cluster in our keyword network) centers on the connectedness of green financial instruments with traditional markets. Keywords like “green bonds”, “clean energy”, “volatility”, “spillovers”, and “portfolio diversification” are prominent. Research in this cluster investigates how the introduction of green assets (like green bonds or renewable energy stocks) affects risk transmission. A consistent finding in this area is that green assets can provide diversification benefits. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, green bonds exhibited hedging properties as their performance was relatively resilient when oil prices collapsed. Influential works by Reboredo et al. and others have quantified spillover indices between green and conventional assets, often using techniques like connectedness measures and vector autoregressions (e.g., Reboredo et al., 2020 on green bond and stock market linkages). This cluster underscores the systemic risk aspect: understanding whether sustainable finance instruments reduce overall financial volatility or introduce new correlations is crucial for investors and regulators. The fact that this is the dominant cluster suggests the risk-spillover narrative is central in sustainable finance research.

The dominant cluster, indicated by the red color, comprises 27 terms that encompass the studies related to the research on the risk transmission of the green bond market. The green bond market is the first green finance market where the greenest investment projects are financed. Hence, scholars from several disciplines have been drawn to the topic of connectedness in sustainability finance; they choose the green bonds as a proxy for the green finance market. They examine and analyze related areas, including the connectedness of green finance, renewable energy, clean energy, CO2 emissions, and overall spillovers from green bonds to sustainable investment. This cluster primarily focuses on the significance of green investing using the funds generated through the bond market. The primary goal of the studies is to understand the advantages of diversifying into green markets. The scholars clearly identified the hedging benefits of green investing during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. This cluster uses the following main keywords: dynamic connectedness, connectedness, volatility, network hedging, portfolio diversification, spillovers, clean energy, green bonds, financial markets, and the COVID-19 pandemic. These issues of green finance study are closely interconnected and form the central focus of sustainability in finance. This group is also unified with other groups, indicating the incorporation of similar concepts throughout several facets of sustainable finance.

Cluster B: Green Technology Innovation and Green Finance

The second cluster (green-colored in our mapping) revolves around financing for green technology and the role of innovation in sustainability. Keywords include “green technology innovation”, “renewable energy”, “environmental regulation”, and “spillover effect” (in the context of technology spread). This theme covers how financial systems support technological solutions to climate change, such as investments in clean tech startups, R&D for renewables, and the diffusion of sustainable technologies. Studies here often intersect with policy, examining how government regulations or subsidies for green innovation affect financial markets and investment flows. A regional focus is notable: China figures prominently as a subject, with research highlighting how Chinese environmental regulations and green finance initiatives have propelled clean energy innovation. Representative papers might analyze, for instance, the impact of green credit policies on firms’ innovation output or how venture capital in cleantech is evolving. This cluster’s strong link to Cluster A indicates that, as new technologies come online, their financial spillovers (like the effect of widespread renewable energy adoption on energy markets and related securities) are a bridging topic between the clusters.

The second green color cluster, known as the green innovation cluster, contains 21 keywords that are connected to green technology innovations and green finance tools utilized for sustainable financing. The cluster encompasses prominent concepts such as green finance, green technology innovation, green innovations, and the spatial spillover effect. This cluster encompasses the knowledge sphere of the sustainable economy. These clusters discuss the knowledge base of how sustainability can be achieved; only innovations of new energy sources can make the real transition to a sustainable future. This cluster includes additional studies on environmental regulation, environmental pollution, and air pollution, demonstrating that implementing clear regulations that prioritize green innovations is the only way to address the challenges posed by climate change. The correlation to other clusters is significant. The first cluster concentrates on the interconnectedness of green bonds, while this cluster investigates green finance as a source for green innovations and establishes the foundation for the digital economy, a crucial component of a sustainable economy. This cluster also identifies China as a hub for green innovations due to its effective environmental regulations, which support the green technological innovations.

Cluster C: Sustainability, Energy Transition, and Economic Growth

The third cluster (blue in our network) encapsulates the macro-level interplay between sustainability efforts, energy transitions, and economic outcomes. Core terms here are “CO2 emissions”, “energy efficiency”, “economic growth”, and “Granger causality”. Essentially, this theme deals with the long-run relationship between green finance initiatives (such as investments in energy efficiency or low-carbon infrastructure) and broader economic indicators like GDP growth or employment. Many studies in this cluster use econometric methods to test hypotheses like “Does renewable energy investment crowd out or stimulate economic growth?” or “Do carbon emissions decrease as green financing increases, and with what lag?”. The presence of “Granger causality” as a keyword suggests numerous papers attempt to establish directionality (e.g., whether financial development causes environmental improvement or vice versa). This cluster often draws from the development economics and macroeconomics literature, linking sustainable finance by arguing that efficient financial markets are needed to fund the transition to a low-carbon economy. The cluster’s insights are vital for policymakers: they hint at whether sustainable finance is aligned with economic development goals or if there are trade-offs. For instance, one line of inquiry is whether aggressive climate-focused financial policies might impede short-term growth (a concern for developing nations) or if they can actually foster a new wave of green economic expansion.

The blue color cluster, having 14 keywords, is characterized by its focus on economic growth with sustainability. This cluster mostly includes terms related to the aspects of renewable energy transition. This cluster concentrates on promoting economic growth while reducing carbon emissions and enhancing energy efficiency. The primary terms in this cluster are CO2 emissions, energy transition, sustainability, energy efficiency, technological innovations, economic growth, spillover effects, and Granger causality. This cluster illustrates ongoing research on the significance of sustainability. This group focuses on promoting economic growth to ensure the protection of the climate. All financial activities prioritize climate health. This cluster is closely interconnected with other clusters, particularly the second.

Cluster D: Renewable Energy Finance and Policy Spillovers

Another theme (appearing as a yellow cluster) specifically focuses on renewable energy projects and how their financing and performance spill over to other sectors. This cluster’s distinct identity comes from terms like “renewable energy sources”, “spillover effect”, “uncertainty”, and “climate change” policy. It overlaps somewhat with Cluster B but is more finance-focused: for example, it includes studies on renewable energy stock indexes, the risk profile of renewable energy investments, and how energy policy uncertainty (say, fluctuating subsidies or carbon prices) translates into financial market volatility. The cluster is highly connected to all others, suggesting that renewable energy finance is a central meeting point for discussions of sustainability in finance. Indeed, many authors in other clusters reference renewable energy finance findings, whether it is using renewable indices as part of a diversified portfolio (linking to Cluster A) or as evidence of the real-economy impact of sustainable finance (linking to Cluster C). A key insight from this theme is the importance of stable and supportive policies: papers often find that consistent government policies on renewables lower financial uncertainty and attract more capital, whereas policy reversals can increase perceived risk, affecting everything from equity costs to insurance in the energy sector.

The yellow color cluster on this network map is created exclusively using renewable energy and its spillover effects on the other sectors of the economy. This cluster is central to all other clusters and has strong connections to other clusters’ energy sources. The cluster is mostly focused on the term’s renewable energy, renewable energy sources, green energy, spillover effect, uncertainty, connectedness network, and climate change. The finance and regulation of renewable energy are crucial for assuring the generation, distribution, and use of clean energy.

Cluster E: ESG Investing and Corporate Sustainability Strategies

While not explicitly separated in the keyword network described above, our co-citation analysis and reading of the literature indicate a cluster oriented around socially responsible investing (SRI) and corporate ESG strategies (this corresponds partly to what we integrated in Cluster A’s interpretation and also appears in the co-citation Cluster 1 described in the original results). This theme encompasses studies on how investors incorporate ESG criteria into portfolio selection, the performance of SRI funds, and how corporate sustainability strategies influence investor behavior. Classic references in this cluster include early studies like (Brzeszczyński & McIntosh, 2014) on SRI performance and (Dawkins, 2018; Pedersen et al., 2021) on ESG portfolios. The co-citation network highlighted that this is a well-established body of literature with many interlinked citations, forming the intellectual backbone of sustainable finance. The emphasis here is on risk-return profiles of sustainable investments and the business case for ESG, essentially asking, “Do investors sacrifice returns for ethics, or can you have both?” and “How does sustainability integration alter portfolio risk?”. Many findings show that ESG investments can achieve competitive returns, and in some cases lower risk, especially over long horizons (Friede et al., 2015 conducted a meta-study indicating a non-negative ESG; performance relation in most cases). This cluster is crucial for mainstreaming sustainable finance, as it provides the evidence base (or lack thereof) that investing responsibly can be financially sound.

These thematic clusters collectively paint a picture of a multifaceted field. Importantly, they are not silos but have cross-linkages. For example, the concept of “spillover” is a common thread: whether it is spillover of shocks (Cluster A, D) or spillover of technology and growth effects (Cluster B, C). This reflects the core interest in connectedness, not just within financial markets, but between finance and the broader ecological/economic system. To validate and complement the cluster findings, we also performed a trend analysis. Figure 5 illustrates a timeline of key topics: in the 1990s, early work was often about ethical banking and microfinance for sustainability; in the 2000s, attention shifted to carbon finance (post-Kyoto Protocol) and CSR in finance; the 2010s saw “green bonds” and “climate risk” explode in frequency, alongside “ESG investing” as a term. By the 2020s, new terms like “transition risk”, “stranded assets”, and “fintech for sustainability” have appeared. This temporal evolution indicates that sustainable finance research has progressively moved from conceptual and voluntary notions (like ethics and CSR) to more concrete, market-based mechanisms and risk considerations. It mirrors how sustainability went from a peripheral concern to a central one in financial decision-making.

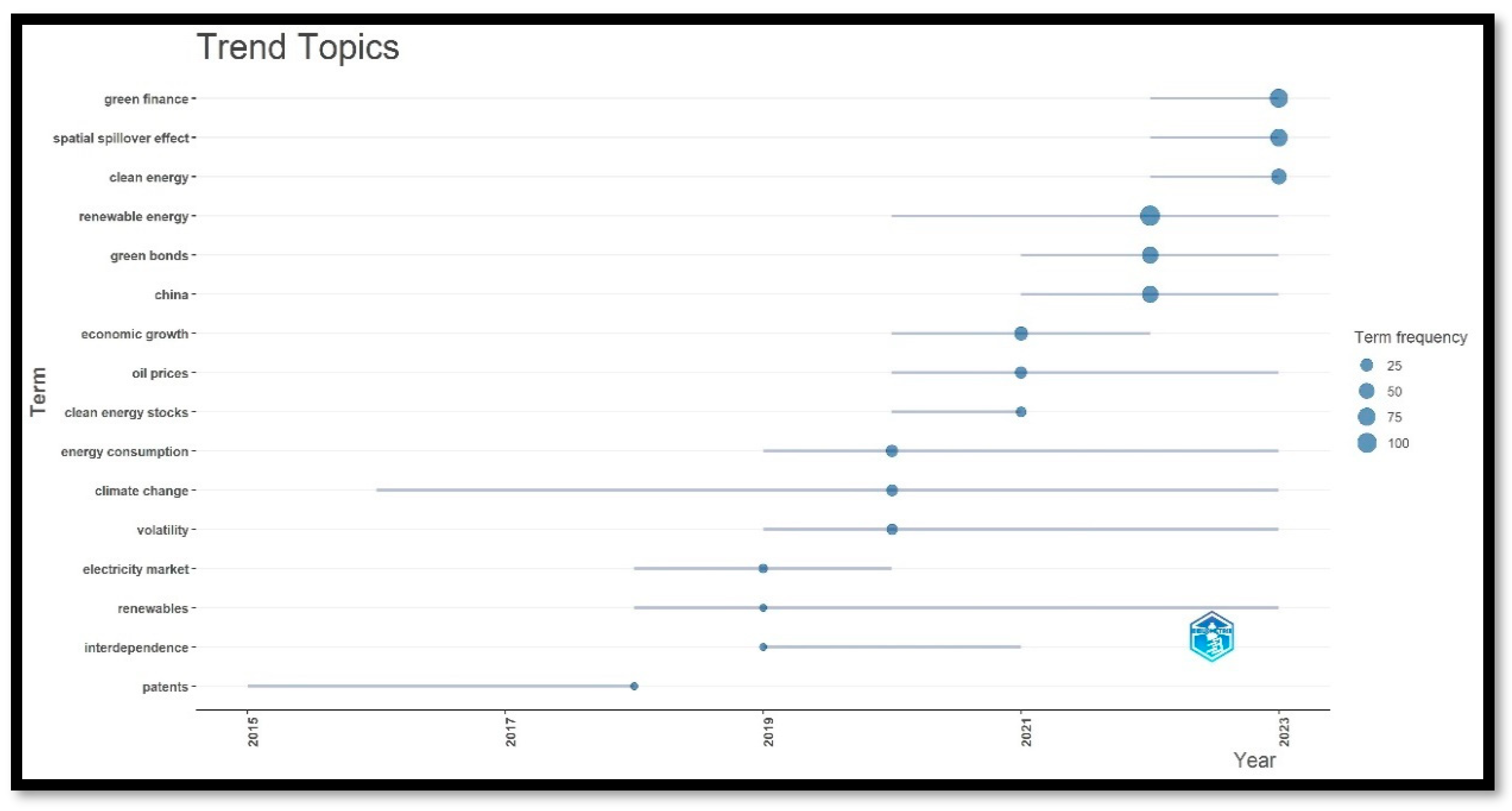

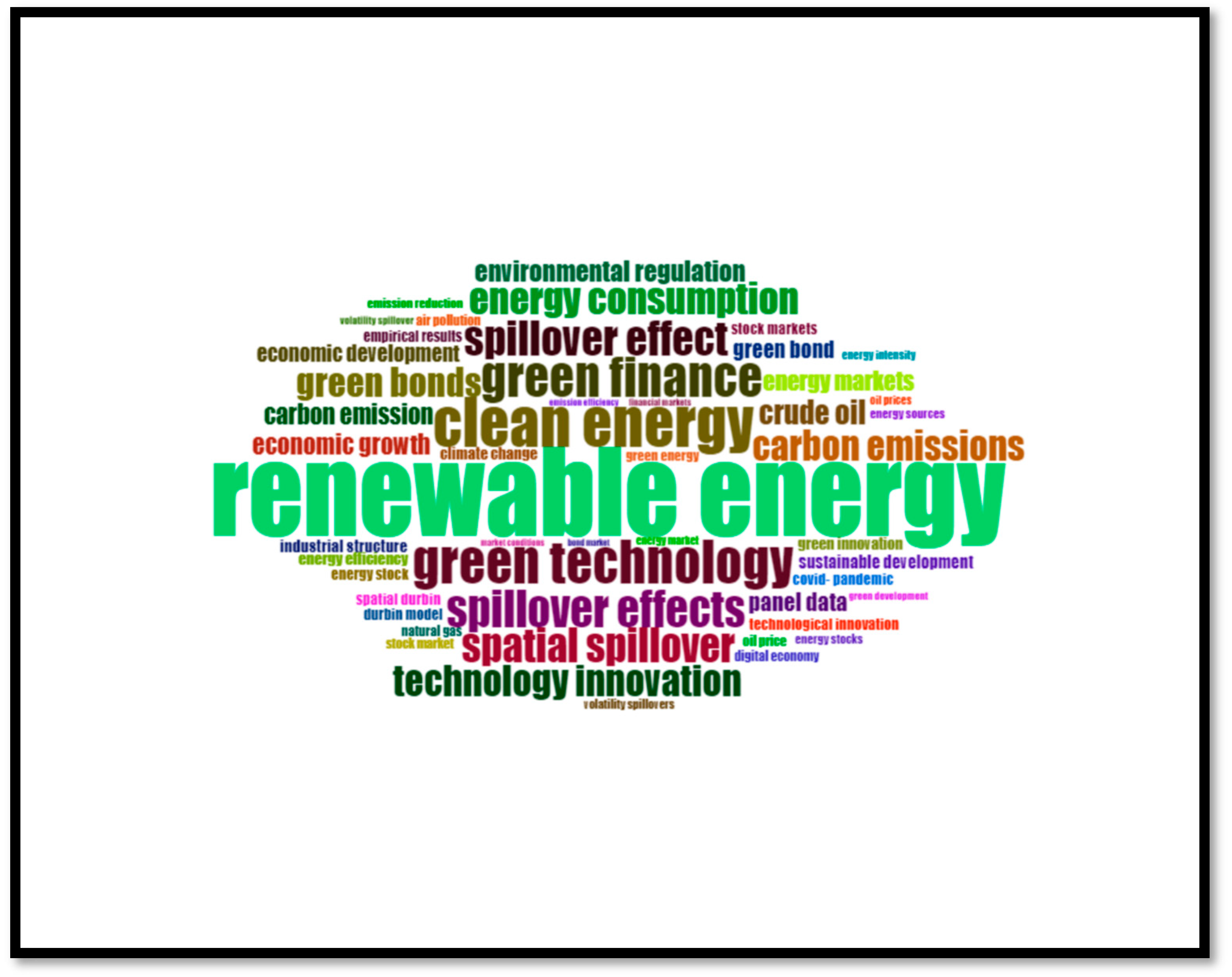

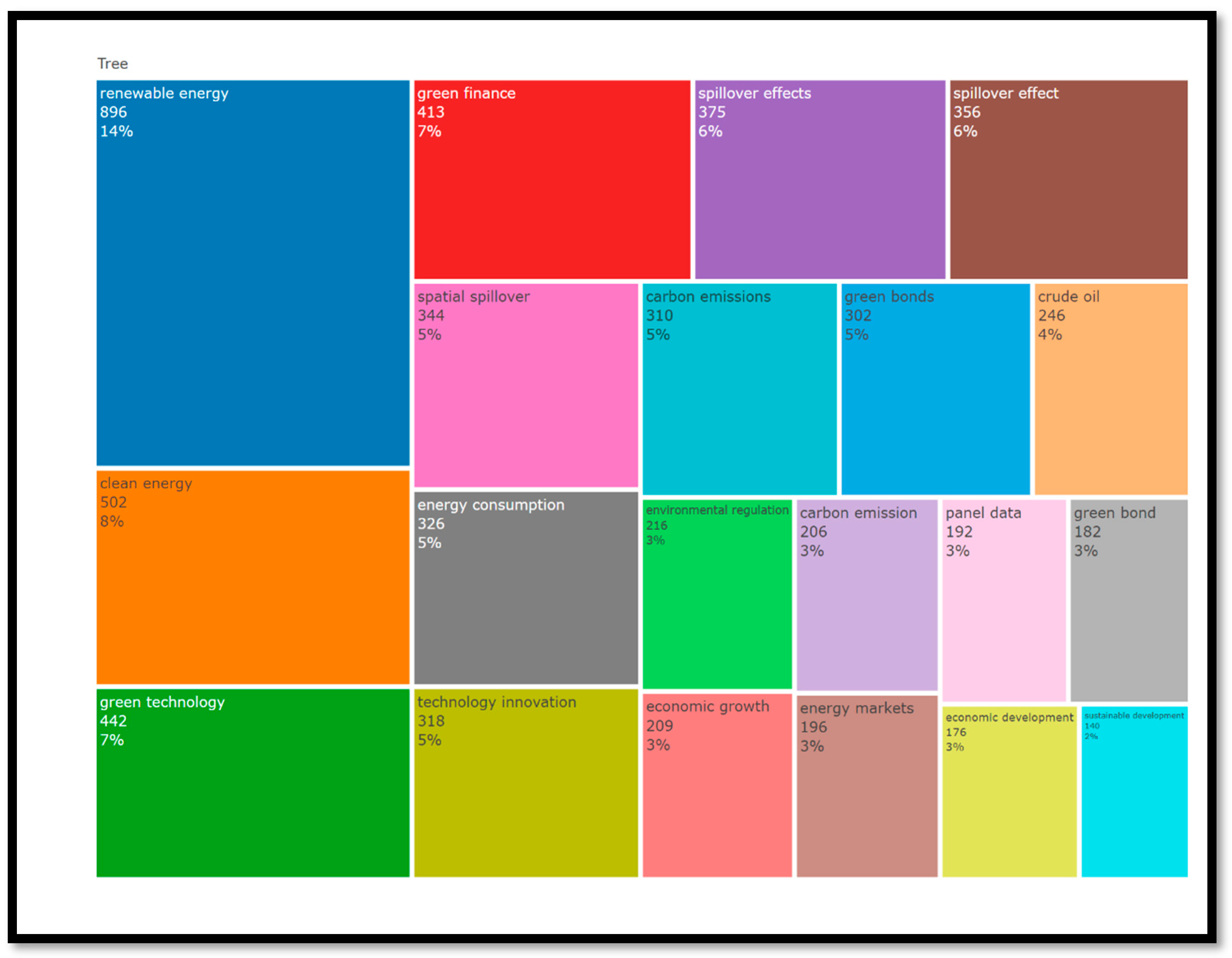

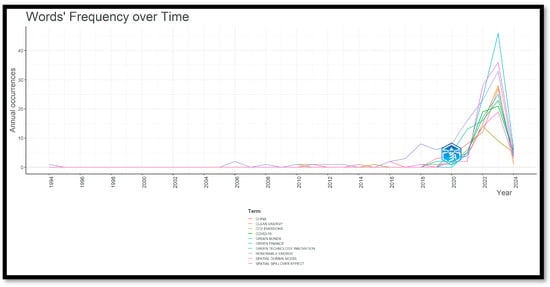

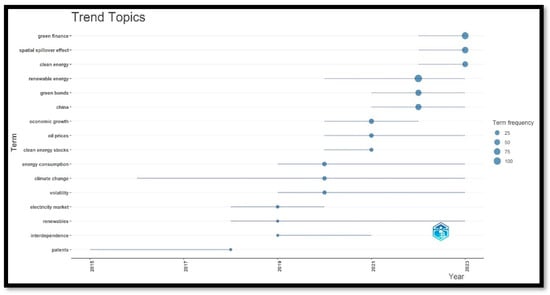

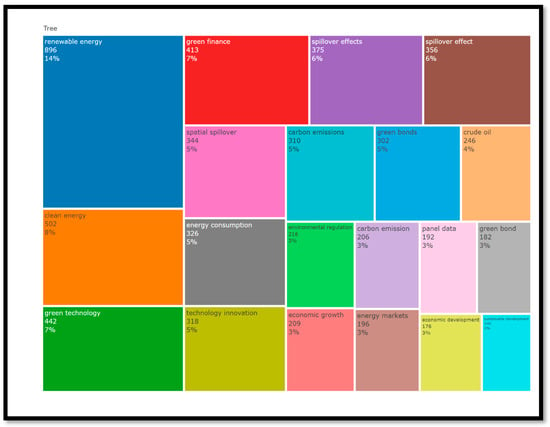

Figure 19 and Figure 20. displays the word cloud and tree map of author keywords, the terms like “impact”, “CO2 emissions”, “renewable energy”, “economic growth”, and “crude oil” are prominently featured, indicating these themes dominate the central narrative and content focus of the research articles. The frequent occurrence of terms such as “volatility”, “impulse-response”, and “connectedness” suggests that studies predominantly explore dynamic relationships and econometric analyses within contexts involving energy, environment, and economics. Figure 21 displays words frequency overtime and Figure 22 demonstrates the trend topics in sustainable finance. Conversely, the abstract word cloud and tree map in Figure 23 and Figure 24 distinctly emphasizes terms like “renewable energy”, “clean energy”, “green finance”, “spillover effects”, and “green technology”, highlighting authors’ intended thematic categorization and research focus. The substantial presence of “spillover effect” and “spatial spillover” underscores the research interest in geographical and economic externalities related to green and sustainable technological innovations.

Figure 19.

Word Cloud of Author Keywords.

Figure 20.

Tree Map of Author Keywords.

Figure 21.

Words’ Frequency over Time—Author Keywords.

Figure 22.

Trend Topics.

Figure 23.

Word Cloud—Abstract.

Figure 24.

Tree Map of Words—Abstract.

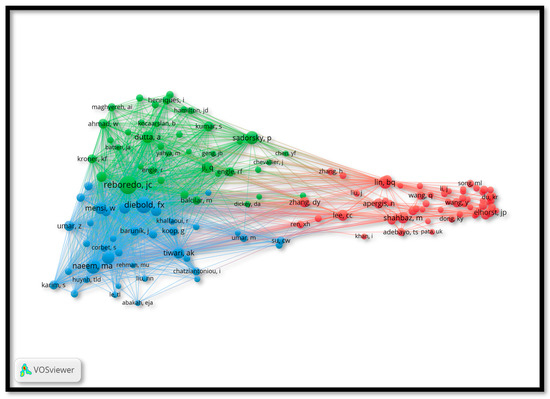

4.10. Co-Citation Analysis

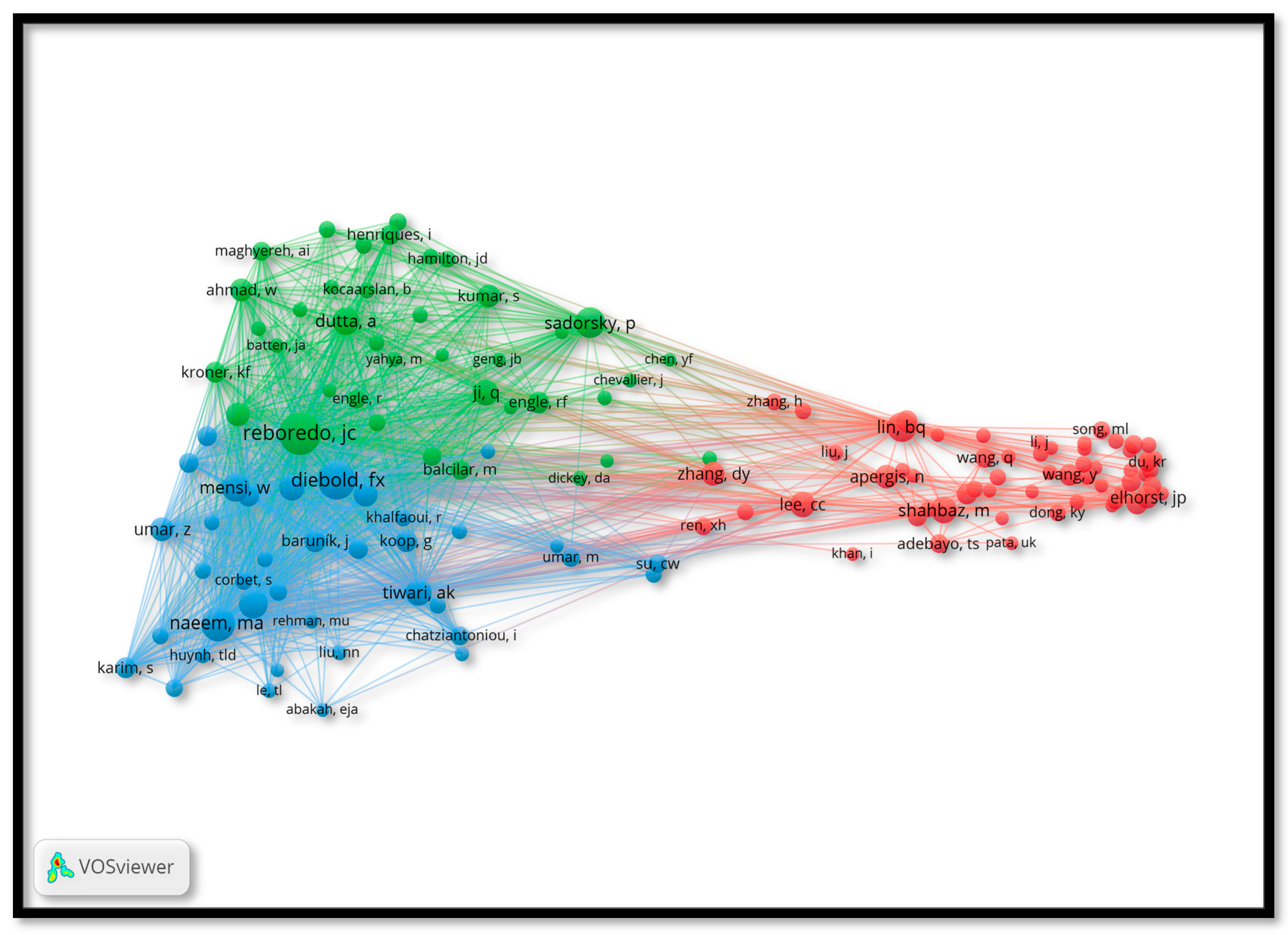

Co-citation analysis is a technique employed to assess the intellectual framework and similarity among authors’ works. The emphasis is exclusively on the number of citations, disregarding the substance of the citations themselves. Clusters form when authors with similar citation patterns reference one another. The clustering of two authors suggests the utilization of similar references by both parties. Figure 25 illustrates a co-citation map analysis, wherein the criterion for inclusion is that an author must possess at least 50 citations. Among 3540 writers, only 137 authors satisfy this criterion, categorized into three distinct clusters. Cluster one (red) comprises 60 authors. Cluster two contains 39 items, whereas cluster three comprises 38 items. The clusters represent the magnitude of the domain’s intensity and the concentration of its density. The authors reference the same work.

Figure 25.

Co-Citation Map—Min-50 Citations-137 Authors.

The red-colored Cluster 1, which is the most extensive cluster on the map, represents publications related to green investment. Green financial investment research has largely concentrated on socially responsible investment, according to the keyword map. Portfolio selection, risk and return, investor behavior, and institutional attitude are the main areas of focus in the study. These writers have the highest level of connectivity inside the cluster and possess strong links in the network.

Cluster 2, green color, is dedicated to addressing inquiries on the appropriateness of financial instruments and their analysis. This cluster has conducted research on issues pertaining to green banking, green bonds, and Sukuk. The writers exhibit a strong link within their cluster but have limited connections outside of it.

Cluster 3: blue shade researchers have investigated the importance of carbon and climate finance. These studies focus on climate policy, modeling, and their impact on the long-term sustainability of the environment. Clearly, this cluster is currently expanding and lacks significant connections both internally and externally. The research on climate and carbon finance is still in its early stages, focusing on a crucial part of sustainability.

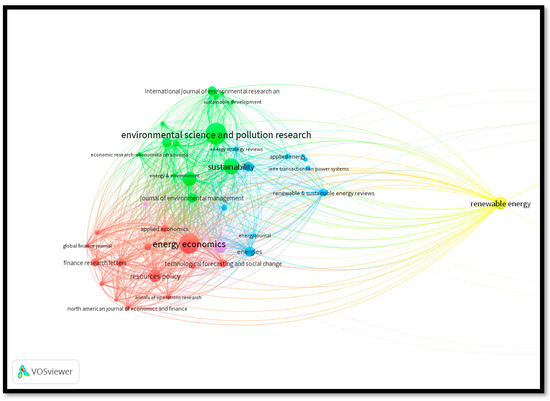

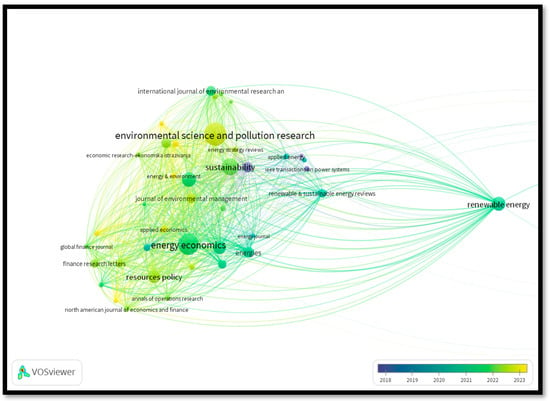

4.11. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis

The bibliographically coupled map of sources is displayed in Figure 26 and Figure 27. Bibliographic coupling is an exhaustive method of evaluating the degree of commonality between the sources. Bibliographic coupling is the phenomenon where two researchers cite the same third study and make references in their bibliographies. Two documents are bibliographically coupled if they share references with one another (Garfield, 2004). According to (Moral-Muñoz et al., 2020) VOSviewer is a valuable tool for producing bibliographic maps that aid in identifying cohesions across documents that reference the same work. The criteria for including sources in the map are a minimum of five documents and at least twenty citations per source. Figure 26 presents a map comprising 46 items organized into five clusters. Cluster 1 (red) comprises 14 sources, Cluster 2 (green) includes 13 sources, Cluster 3 (blue) contains 11 sources, Cluster 4 (yellow) aggregates six sources, and Cluster 5 (purple) consists of two sources. From the map, it is evident that Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Energy Economics, Sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Renewable Energy are the prominent sources and are coupled strongly. The map results align with the findings presented in Table 3.

Figure 26.

Bibliographic coupling Map.

Figure 27.

Bibliographic Coupling Map over Time.

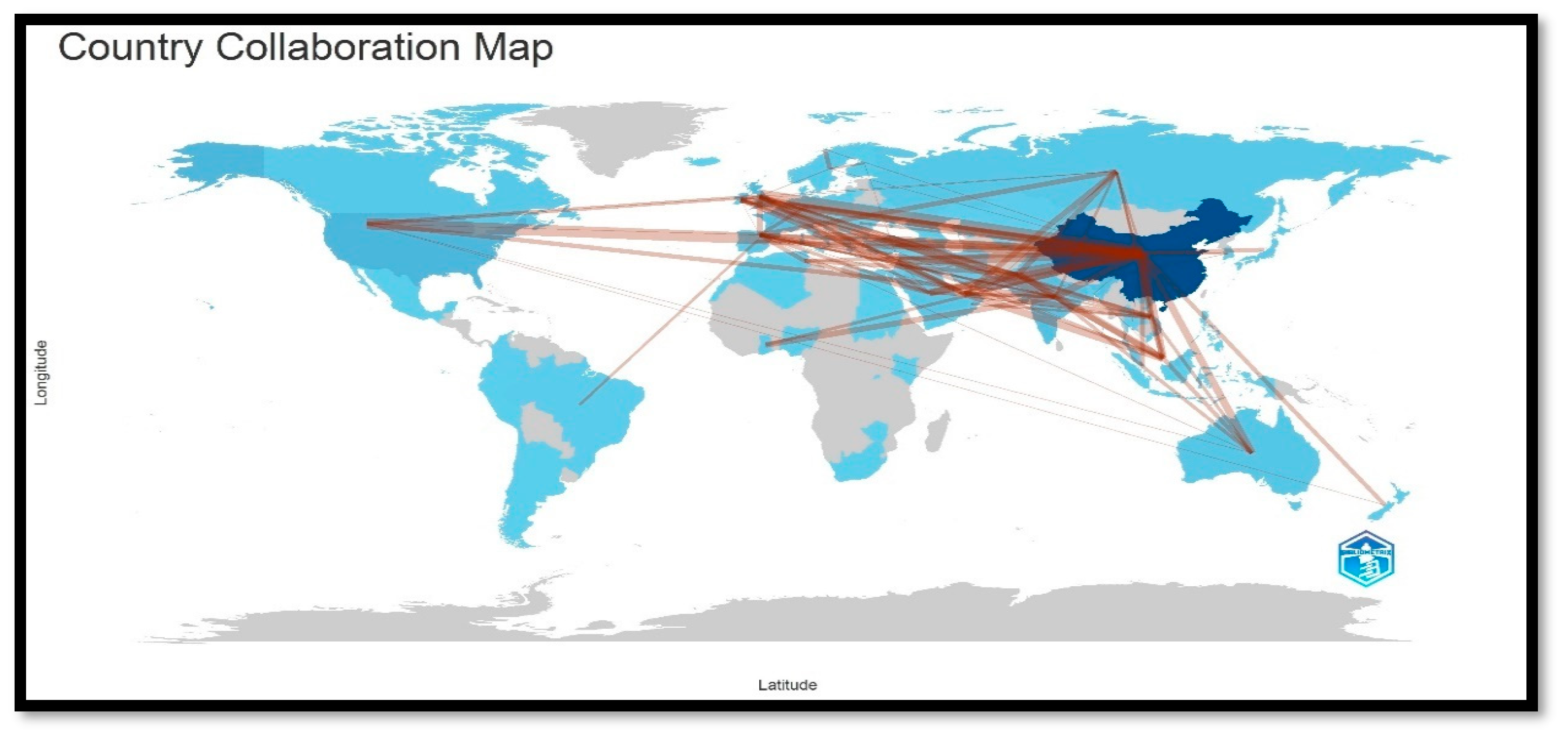

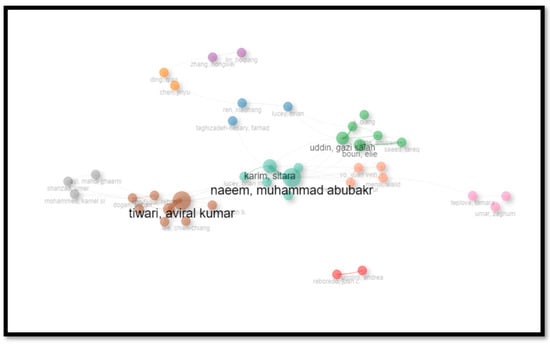

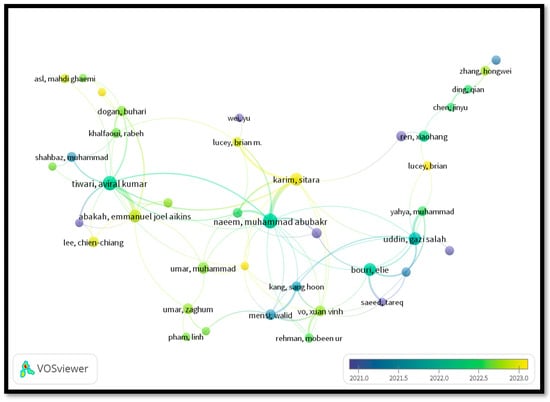

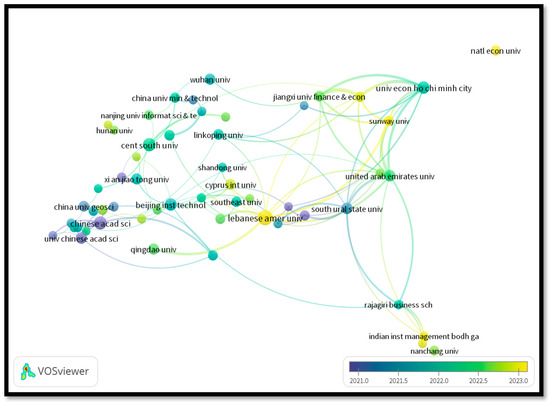

4.12. Collaboration Network Analysis

The collaboration network in connectedness of sustainable finance, as represented by these ten clusters shown in Table 8 and Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31 and Figure 32, highlights the diversity and complexity of research in this field. From foundational scholars in Cluster 1 to interdisciplinary bridge-builders in Cluster 2 and innovative fintech researchers in Cluster 10, each cluster contributes uniquely to the development of sustainable finance. Understanding the roles of key authors in these clusters helps identify the interdisciplinary nature of the field, the importance of regional and global contributions, and the emerging trends in sustainable finance research. As these clusters continue to evolve, they will drive both academic growth and policy advancements in addressing global sustainability challenges.

Table 8.

Collaboration Network.

Figure 28.

Collaboration Network—Authors.

Figure 29.

Collaboration Network—Authors over Time.

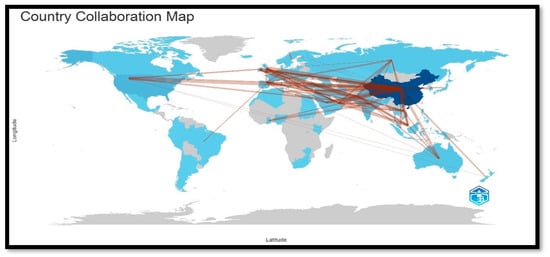

Figure 30.

Collaboration Network—Countries.

Figure 31.

Collaboration Network—Institutions.

Figure 32.

Collaboration World Map.

Cluster 1: Foundational Researchers and High Internal Collaboration

Key Authors: Juan C. Reboredo, Andrea Ugolini

Cluster 1 consists of foundational authors who have a high degree of internal collaboration within their research community. The low betweenness scores of authors like Juan C. Reboredo and Andrea Ugolini indicate that they are not key intermediaries between other clusters but are central within their own group. These authors contribute to focused research topics in sustainable finance, collaborating extensively within their specialized areas. They likely work on specific issues such as climate finance or green bonds, maintaining close-knit relationships with other members of the cluster.

Cluster 2: Interdisciplinary Scholars with Diverse Contributions

Key Authors: Xiaohang Ren, Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary, lucey, brian Asl, Mahdi Ghaemi, Mohammed Kamel Si, Shahzad Umer

Cluster 2 includes interdisciplinary scholars whose work spans multiple domains, from finance and economics to environmental science and policy analysis. These authors contribute to bridging the gap between theoretical models in finance and practical applications in sustainability. Their betweenness scores suggest that they serve as intermediaries between different fields, allowing for a holistic approach to sustainable finance. Their work often integrates insights from socioeconomic factors, policy analysis, and market dynamics.

Cluster 2 includes authors with high betweenness scores, such as Xiaohang Ren and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary, indicating that they serve as bridge-builders between different research areas. These authors play a critical role in connecting various subfields of sustainable finance, such as green finance, renewable energy, and climate risk management. Their ability to collaborate across clusters makes them central to fostering interdisciplinary research and facilitating the flow of ideas between distinct research domains.

Cluster 3: Emerging Scholars and Specialized Research Areas

Key Authors: Bouri Elie, Uddin Gazi Salah, Yahya Muhammad, Dutta Anupam, Ji Qiang, Saeed Tareq

Cluster 3 represents emerging scholars who focus on specialized or niche areas within sustainable finance. These authors might be early-career researchers contributing to innovative subfields such as impact investing, green fintech, or socially responsible investing. While their betweenness scores are moderate, indicating they are still establishing themselves as intermediaries, they bring new perspectives to the field. Over time, as their influence grows, they will likely expand their collaboration networks and become more integral to interdisciplinary efforts.

Cluster 4: Large Collaborative Teams and Multi-Institutional Research

Key Authors: Lin, Boqiang, Zhang, Hongwei

Cluster 4 is composed of large, collaborative research teams that tackle complex and broad challenges within sustainable finance. These authors typically work across multiple institutions and countries, as indicated by their high betweenness scores. They facilitate collaboration among various academic and research communities, integrating diverse expertise from different parts of the world. The authors in this cluster contribute to large-scale research projects addressing global challenges such as energy transition, financial risk due to climate change, and green technology development.

Cluster 5: Influential Authors with Broad Global Impact

Key Authors: Chen, Jinyu, Ding, Qian

Cluster 5 is home to the most influential authors in the field of sustainable finance. These authors are recognized for their global impact in both academic research and policy development. With high PageRank and betweenness scores, authors in this cluster are at the center of the research network, connecting different clusters and shaping the future of sustainable finance research. They often lead large-scale research efforts, influencing the development of sustainable financial models and regulatory frameworks.

Cluster 6: Regional Leaders in Sustainable Finance

Key Authors: Tiwari, Aviral Kumar, Abakah Emmanuel Joel Aikins,

Lee, Chien-Chiang, Dogan Buhari, Khalfaoui Rabeh, Shahbaz Muhammad, Adekoya, Oluwasegun B., Nasreen Samia

Cluster 6 features regional leaders in sustainable finance, authors who contribute significantly to the field within specific geographic areas or economic contexts. These authors may focus on regional financial markets, economic policies, or climate finance challenges specific to certain countries or regions. Their research may be particularly relevant for policymakers and financial institutions operating in those regions. Though they may have lower betweenness than authors in other clusters, their contributions are essential for localized studies of sustainability.

Cluster 7: High-Impact Authors in Green and Social Finance

Key Authors: Umar, Zaghum, Pham, Linh, Teplova, Tamara Mensi, Walid, Vo, Xuan Vinh, Kang, Sang Hoon, Rehman, Mobeen Ur

Cluster 7 focuses on the intersection of financial technology (fintech) and sustainability. Authors in this cluster are exploring how technology can be used to drive green finance innovations. This includes the development of blockchain for sustainable investment, AI-driven financial models, and digital platforms for sustainable finance. Their research is critical for pushing the boundaries of what is possible in sustainable finance through technological advancements. These authors are at the cutting edge of fintech solutions that facilitate green bonds, carbon trading, and sustainable management.

Authors in Cluster 7 focus on high-impact topics in green finance and socially responsible investing. These authors often work on studies that explore the intersections between finance and sustainability, especially in relation to corporate social responsibility (CSR), ESG investing, and social impact finance. Their collaboration networks are often cross-disciplinary, bringing together finance professionals, environmental scientists, and policy experts. With their high PageRank scores, these authors are often at the forefront of green bonds and climate-related financial innovations.

Cluster 8: Researchers in Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

Key Authors: Naeem, Muhammad Abubakr, Karim, Sitara, Umar Muhammad, Shahzad Syed Jawad Hussain, Farid Saqib, Lucey Brian M.

Cluster 8 is centered around authors who specialize in the policy and regulatory aspects of sustainable finance. These authors study the role of government regulations, financial policies, and international agreements in promoting sustainable finance. They work closely with governmental bodies, financial institutions, and NGOs to examine the effectiveness of regulations such as the Paris Agreement and climate risk disclosure frameworks. Their research directly impacts how sustainable finance can be integrated into national and international policy agendas.

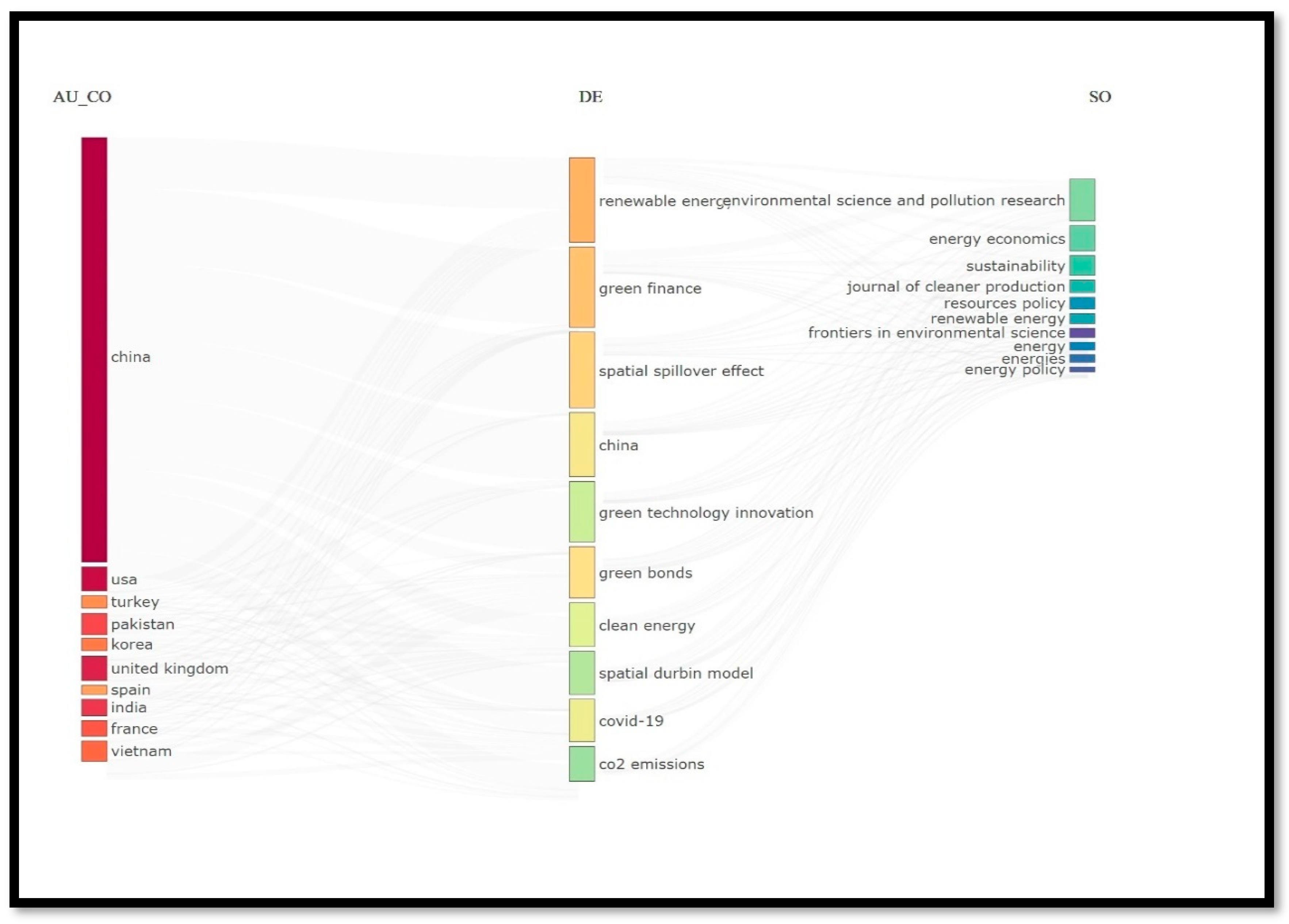

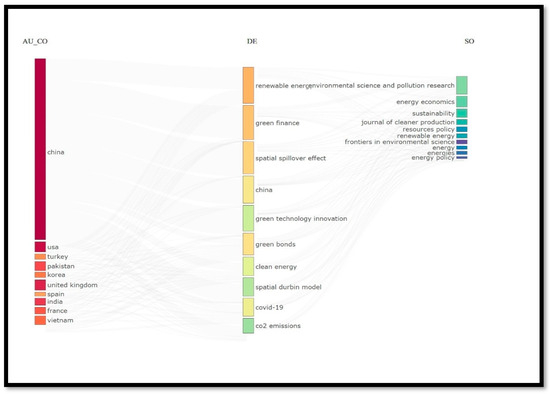

4.13. Three Field Plot (Or Sankey Diagram) Associating Countries–Keywords–Sources

Figure 33 displays a three-field plot that visually maps the relationships between contributing countries (AU_CO), research themes or keywords (DE), and the prominent journals (SO) publishing research on sustainable finance and its connectedness. On the left, China is the most prolific contributor, dominating the global research output in this field, followed by other countries such as the USA, Turkey, Pakistan, and Korea. The middle column highlights the most frequently explored topics, including “renewable energy”, “green finance”, “spatial spillover effect”, “green technology innovation”, and “CO2 emissions”, showcasing the thematic focus of sustainable finance research. These themes align with pressing global challenges such as the energy transition, climate policy, and sustainability. The right column lists the most influential journals publishing in this domain. Journals such as Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Energy Economics, and Sustainability emerge as core contributors, reflecting Bradford’s Law of a concentration of research output in a few high-impact sources. The connections between countries, themes, and journals emphasize the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of research in this field, with China playing a central role in addressing themes like renewable energy and green finance through high-impact journals. This visualization underscores the geographic and intellectual hubs of sustainable finance connectedness research, offering valuable insights for future studies and collaborations.

Figure 33.

Three-Field Plot (or Sankey diagram) associating Countries–Keywords–Sources.

5. Discussions of Results

The findings of our bibliometric analysis carry several significant implications for both research and practice in sustainable finance. Here, we interpret the results in light of the broader literature and discuss how they advance understanding in the field.

Publication Trends and Growth of the Field: Our analysis confirms that sustainable finance research has grown exponentially, especially in the last decade. Figure 1 illustrates the annual number of publications from 1994 to 2024. From the mid-1990s through the early 2000s, the output was minimal, often fewer than five papers per year, reflecting the nascent stage of the field when concepts of sustainability in finance were just emerging. The growth remained modest until around 2010, after which a noticeable uptick occurred. The year 2015 stands out as an inflection point: annual publication counts roughly doubled compared to the early 2010s, and this acceleration continued through the late 2010s. By 2021 and 2022, we observe a peak with over 150 articles published each year. The cumulative annual growth rate of publications is about 16.1%, indicating a very rapid expansion. This timing aligns with external developments; notably, 2015 saw the Paris Climate Agreement and the adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, events that put sustainable finance in the spotlight of both policy and academia. Post-2015, there was also a surge in investor interest in ESG products and regulatory initiatives (for example, the European Commission’s sustainable finance action plan in 2018), which likely spurred scholarly research to analyze these trends. In addition to the raw count of papers, the breadth of outlets has increased. Before 2010, only a handful of journals (like niche ethics or environmental economics journals) featured sustainable finance work; now, mainstream finance and management journals regularly publish on these topics. Our dataset spans 228 journals, indicating a wide dissemination of research. We also note that about 25 of the items are review papers (systematic literature reviews or conceptual pieces), mostly appearing after 2018. This suggests that as the field matures, scholars are synthesizing knowledge and evaluating the State-of-the-Art—a sign of consolidation and recognition of sustainable finance as a distinct research domain. Geographically, the contribution to this growth is global; moreover, a significant portion of recent publications originates from authors in China, the United States, and Western Europe. We will detail the country’s contributions in a later subsection, but it is worth noting that China’s rise in output during the late 2010s strongly influenced the global publication trend. In fact, China alone accounts for a large share of the post-2015 surge, reflecting heavy academic and governmental emphasis on green finance domestically.