1. Introduction

Tax avoidance remains a persistent economic and financial challenge in modern economies and is prevalent in many countries. In particular, tax avoidance represents a significant challenge for economies worldwide, undermining the equitable distribution of fiscal burdens and eroding the financial foundations necessary for public goods and services. Taxes serve as the primary means for governments to fund public administration and provide public services. However, due to the substantial cost involved in monitoring tax compliance, tax avoidance has been a concept as old as taxation itself (

Smith, 2020). Understanding the factors that influence an individual’s decision to pay taxes is a complex task. Various research methodologies have been employed to uncover unique insights, including field experiments, lab experiments (

Mascagni, 2018), observational studies, surveys and questionnaires (

Olsen et al., 2018), case studies, comparative and cross-country studies (

Cummings et al., 2009), as well as econometric and statistical analyses (

Habib & Jiang, 2015).

A foundational model proposed by

Allingham and Sandmo (

1972) indicates that taxpayers evaluate the advantages of tax evasion in relation to the potential risks of being detected and facing penalties. Although empirical research (

Frey & Torgler, 2007;

Kleven et al., 2011;

Yitzhaki & Slemrod, 1987) has enhanced our comprehension of tax compliance, it frequently examines individual factors in isolation, neglecting the interplay of gender, firm size, and legal status across different tax rates and audit probabilities. In contrast, our study utilizes a 3 × 3 factorial design that incorporates these variables, thereby addressing existing gaps in the literature and providing new perspectives for both theoretical frameworks and policy implications.

While prior research provides important perspectives on tax compliance; however, it frequently overlooks the interplay between gender, entity size, and legal status. Gender may influence individuals’ risk tolerance and their level of trust in governmental institutions, whereas socioeconomic and cultural elements also play a significant role in the income reported. Larger entities generally have access to greater resources and enhanced visibility, in contrast to smaller businesses, which often encounter comparatively higher compliance costs. Tax compliance is conventionally understood as the extent to which taxpayers accurately declare their income and fulfill their tax responsibilities. This conventional definition, however, tends to adopt a uniform perspective that overlooks the varied regulatory demands placed on different types of legal entities. In our research, we categorize tax compliance among self-employed individuals, partnerships, and corporations. Self-employed taxpayers typically operate under more straightforward reporting frameworks and may encounter less rigorous administrative scrutiny, which can both enhance compliance and heighten the risk of tax compliance due to a lack of professional guidance. Conversely, partnerships and corporations are subject to more rigorous regulatory requirements, including compulsory audits, comprehensive financial reporting, and intricate tax planning obligations. These distinctions are informed by theoretical models such as the Allingham–Sandmo framework, which posits that individuals assess the potential advantages of tax evasion against the likelihood of detection and the severity of associated penalties. By explicitly recognizing these differences, our research elucidates how compliance expectations differ according to legal classification. These factors create a complex landscape for tax compliance, influencing how entrepreneurs adhere to tax regulations.

Our study contributes to this field by examining the relatively unexplored behavioral differences in tax compliance among entrepreneurs (business owners). Specifically, we focus on Greek enterprises and consider the combined effects of gender, entity size, and legal status on tax compliance. By shifting the focus from the general population and corporations to actual business decision-makers, our research seeks to address a significant gap in the literature, highlighting the diversity in compliance behavior and underscoring the importance of considering a broader spectrum of decision-makers and tax determinants in tax compliance research. In addition, our study focuses on Greece, which serves as a compelling case study for research on tax compliance, owing to its unique fiscal landscape and cultural dynamics. In recent years, the country has encountered substantial economic difficulties, including extended periods of fiscal austerity, elevated public debt levels, and comprehensive economic reforms, all of which have significantly influenced taxpayer behavior. The interplay of these economic strains with a distinctive tax culture characterized by particular societal perceptions of taxation makes the Greek situation especially pertinent, not only within the Balkans but also across the wider European Union and the Euro Zone.

These context-specific aspects provide a unique backdrop that could influence tax compliance behaviors among Greek company owners, particularly when considering determinants such as gender, entity size, and legal status. Furthermore, the Greek context is enriched by high rates of entrepreneurship and the prevalence of small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), which, despite the economic turmoil, continue to be a vital component of the economy. To capture these dynamics, the following research questions are identified as relevant, along with the corresponding objectives of this study, as detailed in

Table 1.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the results of our field experiment.

Section 3.1 offers a comprehensive review of existing literature on tax compliance experiments. The methodology and the overall experimental design are presented in

Section 3.2.

Section 4 discusses the various policy-relevant implications of our study as well as its main limitations along with fruitful areas for future research directions. Finally, the paper ends with some concluding remarks.

2. Results

The compliance rate of entrepreneurs, which is defined as the ratio of the declared income to the income earned during a specific experiment period, is the primary focus of the analysis. In subsection below, we analyze the intricacies of this subject, providing a more detailed explanation and examination of the compliance rate.

2.1. Average Compliance

We begin by offering a broad overview of the summary statistics. We then present findings from non-parametric tests conducted on personal data to examine the effect of familiarity with firm characteristics on tax compliance. The correlation coefficients between variables of interest are displayed in

Table 2. To strengthen these findings, regression analysis is then applied.

Table 3 presents the average compliance rates for participants across various treatments, using the average behavior of each subject throughout the experiment as the unit of observation. Further,

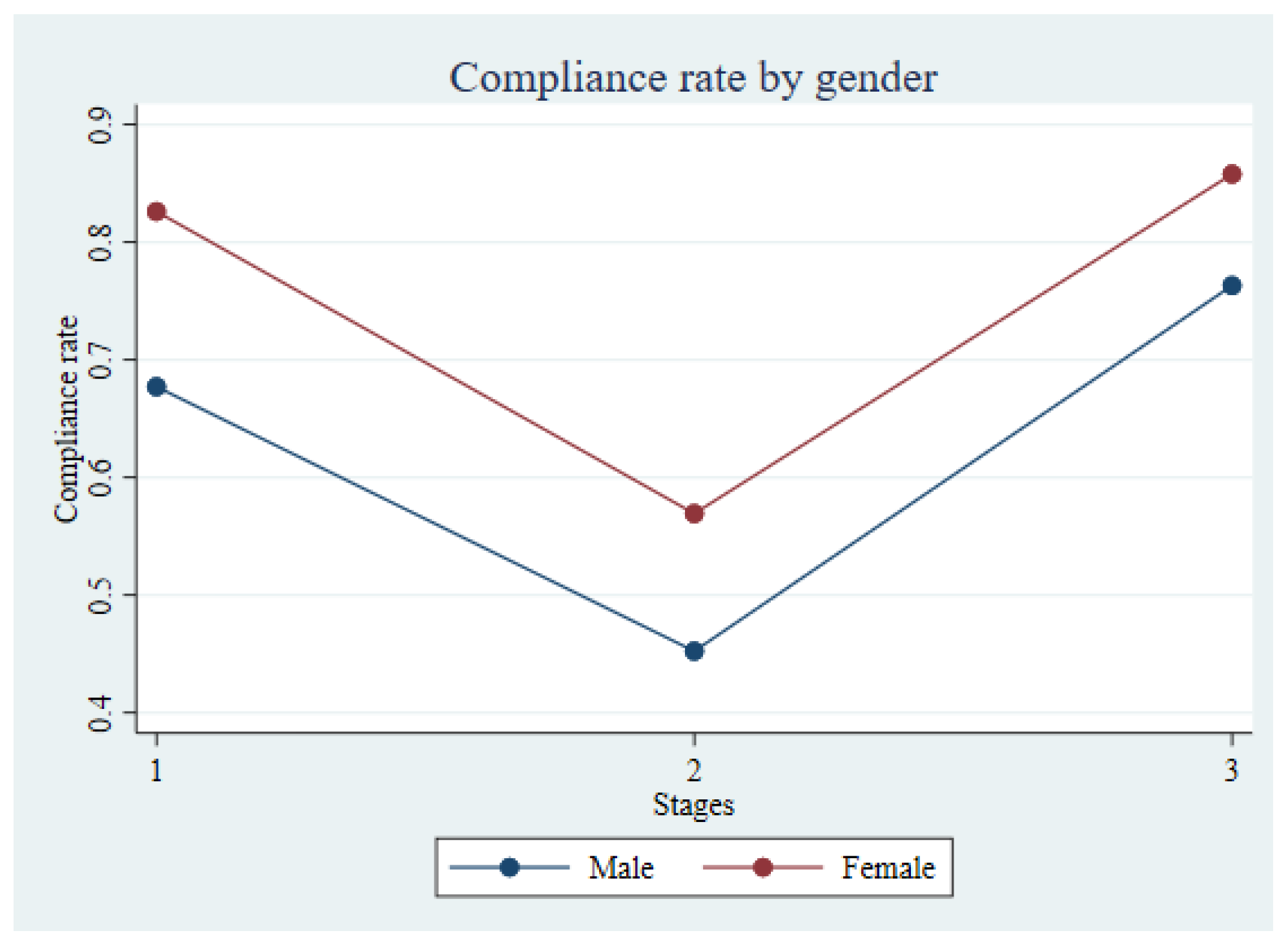

Figure 1 reflects the medium compliance rate per round and gender. Continuing, the following charts (

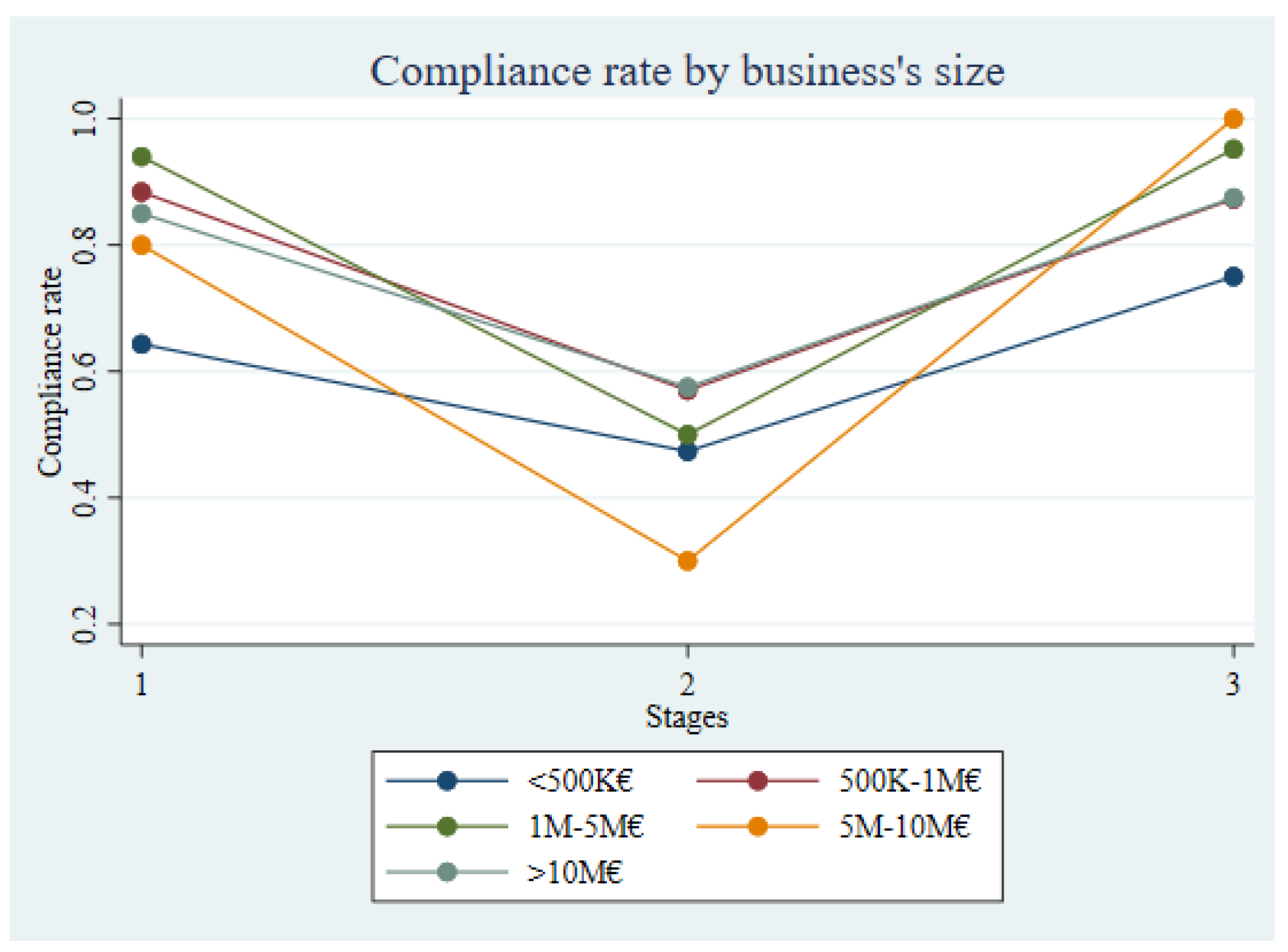

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) depict the average compliance rate by firm size, legal status, and industry at each stage. Moreover, in this subsection, we examine the impact of increasing the probability of audit. Specifically, we compare the mean compliance rates between different samples and treatments using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test (MW). First, we focus on the effect of doubling the audit probability when it is known, comparing treatments P5 and P10. The results reveal a statistically significant effect on the average compliance rate of the subjects (z

,

). This suggests that increasing the probability of audit leads to a notable change in the compliance behavior of the participants.

Next, we explore the effect of an unknown audit probability on behavior. We compare the treatment with an unknown control rate (UP) with the corresponding treatment where the control rate is known (P5). The analysis demonstrates a statistically significant difference in the mean compliance levels of the entrepreneurs (z , ). This indicates that the presence of uncertainty about the probability of audit has a substantial impact on compliance behavior. The statistical significance of the findings underscores the significance of audit probability in shaping tax compliance behavior.

2.2. Distribution of Compliance

When analyzing compliance data, focusing solely on treatment averages may overlook the considerable heterogeneity present in the data.

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 display the compliance level of two-way plots, where the average compliance of each subject is considered as the unit of observation. This visualization demonstrates that despite the continuous nature of the compliance measure, two distinct types of behavior emerge: individuals who consistently report their income honestly throughout the experiment and those who do not. To assess the significance of these differences in behavior, we conducted the KS test for equality of distributions. The results indicate that changing the audit probability from 5% (P5) to 10% (P10) resulted in significant differences in the compliance distribution, specifically among female participants in the two rounds (Male: D = 0.460,

p = 0.000; Female: D = 0.591,

p = 0.000). Similarly, the change in audit probability from 5% (P5) to unknown (UP) showed statistically significant differences for both genders (Male: D = 0.600,

p = 0.000; Female: D = 0.632,

p = 0.000).

Result 1. A higher absolute tax range causes a lower degree of tax compliance, and when the audit probability is ambiguous, it leads to a significant change in mean compliance compared to when the audit probability is known; moreover, doubling the fine rate for non-compliance under ambiguous audit possibilities results in significantly higher mean compliance between the genders.

Our analysis reveals an interesting finding regarding the compliance rate in the second stage of the experiment. Contrary to expectations, we observed a decrease in the compliance rate when the tax rate increased. This suggests that participants were less inclined to report their income honestly when faced with a higher tax rate. To support this observation, we conducted a statistical analysis using the KS test. The results indicate a significant difference in the distribution of compliance between the first and second stages of the experiment, with p-values of 0.000 for both Stage 1 vs. Stage 2 and Stage 2 vs. Stage 3 comparisons (Stage 1,2: D = 0.484, p = 0.000; Stage 2,3: D = 0.621, p = 0.000, KS test). When comparing groups of subjects under the same experimental conditions, we observe that the percentage of fully compliant males is significantly lower in all treatments, with all comparisons being significant at the 1% level. The distribution of compliance also shows a significant difference between males and females (D = 0.209, p = 0.002, KS test).

Males exhibit lower rates of full compliance compared to females, as evidenced by the lower percentage of fully compliant males and the significant differences in compliance distributions. Once the possibility of audit was uncertain, we observed that doubling the fine rate for non-compliance led to a significantly higher mean compliance rate among both genders. This suggests that raising the penalty for not following rules positively influenced behavior towards compliance, regardless of gender. The impact of the penalty on compliance behavior was particularly evident in the context of ambiguity, where subjects were uncertain about the probability of an audit. According to the results, the threat of higher penalties can act as a deterrent and motivate individuals to comply with tax regulations.

Result 2. The likelihood of tax compliance is higher among women compared to men, and this compliance is further influenced when the probability of an audit is doubled; moreover, there is a causal relationship between tax avoidance and the size of a company.

Our findings are consistent with previous research (

Coricelli et al., 2010;

Fortin et al., 2007;

Frey & Torgler, 2007;

Giese & Hoffmann, 2000). These studies also reported significant differences in tax compliance behavior between men and women (

Blaufus et al., 2017;

Bühren & Kundt, 2014;

Pántya et al., 2016). In our specific analysis, we found a statistically significant difference between the mean compliance rates of men and women (D = 0.209,

p = 0.002, KS). Further examining the effect of ambiguity on control probability leads to significant changes in the distribution of compliance for both sexes. The (KS) test shows statistically significant differences in the adherence distributions for males (D = 0.600,

p = 0.000) and females (D = 0.632,

p = 0.000) when comparing the unknown control probability (UP) treatment with known control probability condition (P5). Concluding, when control probabilities are unclear, individuals may exhibit different compliance patterns compared to when control probabilities are known. The findings are consistent with the outcomes of earlier research (

Kamleitner et al., 2012;

Thatcher et al., 2016). These studies (

Habib & Jiang, 2015;

Thornton & Byrd, 2013) also revealed significant differences in how firms with smaller annual total assets dealt with tax compliance. Based on our findings, there appears to be a comparable correlation between asset size and compliance rates, and firms with smaller assets are more likely to have lower levels of tax compliance. Statistical analysis using the KS test confirmed a significant difference in compliance rates (D = 0.950,

p = 0.000).

Result 3. Self-employed tend to be less compliant.

The results of our study indicate a statistically significant difference in compliance rates depending on the legal status of the firm, with self-employed people having the highest concentration and general partnerships having the lowest. This finding raises the possibility that different compliance behaviors may exist for these various legal structures. According to the KS test, there is a significant statistical difference in the compliance rates between these categories (D = 0.967,

p = 0.000). The statistically substantial discrepancy shows that the compliance rates among the various legal regimes differ noticeably. Our results are consistent with

Fiorio and D’Amuri (

2005),

Plumley (

1996),

Kirchler et al. (

2008), and

Halla (

2012).

2.3. Regression Analysis

Our primary analysis begins by examining the results of the ANOVA method (

Table 4). We want to emphasize the importance of the Contrast Test results in

Table 5 and

Table 6, which provide a convenient way to assess the main effects and interactions among our key variables. The goal is to achieve a simpler and more easily understood set of results from the tests, specifically to determine whether there are significant differences in the average values among the groups. As depicted in

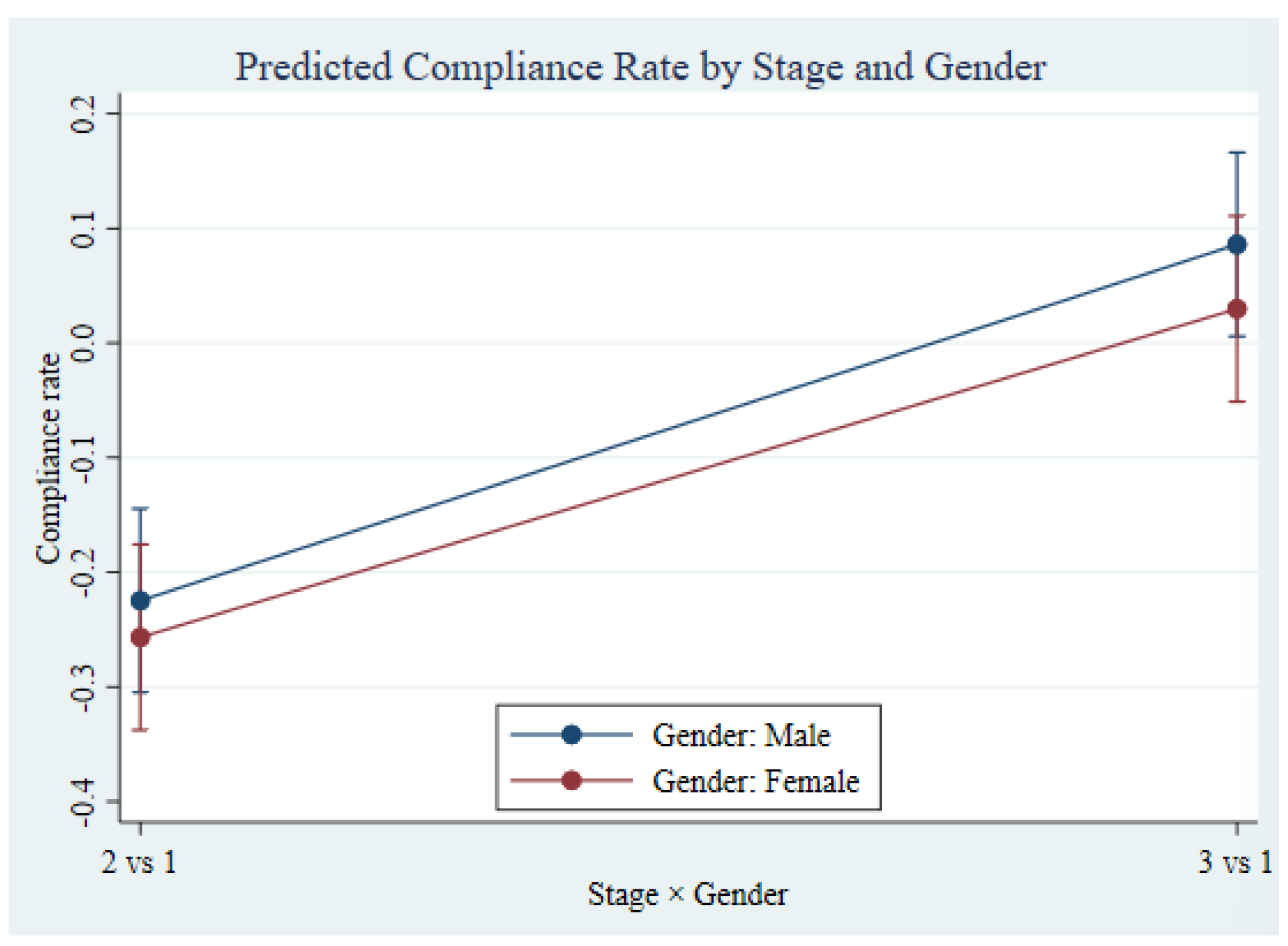

Table 6, men’s compliance noticeably decreases from Stage 1 to Stage 2 by about 0.22 points, and this difference is statistically significant. Similar trends are shown in women, whose compliance falls significantly by 0.24 points, exceeding the reduction in compliance observed in men following the change from Stage 1 to Stage 2. On the other hand, Stage 3 male entrepreneurs show an expected to 0.08 unit increase in compliance, perhaps as a result of the higher fines associated with random tax audits. However, it does not seem like this condition affects female business owners. These results closely resemble those obtained through OLS regression (

Table 7). Notably, the OLS regression analysis produced an

value of around 0.42, which suggests a moderate level of fit. This outcome aligns with the natural variability found in individual behavioral data. In the context of experimental investigations into tax compliance, various unobserved variables can affect the decision-making processes of participants, resulting in moderate values even when significant relationships are identified by the model. Previous studies (

Kleven et al., 2011;

Razen & Kupfer, 2023) have reported similar or lower levels of fit, reinforcing the robustness and significance of our findings despite the moderate explanatory capacity. This instability is representative of the complex nature of the human behavior and the variety of factors that influence tax compliance.

Essentially, these results help us understand how changes in tax rates and audit probabilities affect compliance rates in relation to gender. Since the overall impact of the stages is statistically significant, we can further investigate how they affect gender. We compare the responses of men and women at each stage to examine the direct effects of gender (

Figure 5). Focusing on the row label (2 vs. 1), it signifies an evaluation comparing whether the mean compliance rate in the first stage is equivalent to that in the second stage. The subsequent three rows follow the same approach, scrutinizing whether there exist noteworthy distinctions in the mean compliance rates across various stages. It is noteworthy that, in the case of women, the transition from the third stage to the first stage did not have a statistically significant impact on their compliance.

First, we employ a standard OLS model as a benchmark, with the average compliance rate serving as the dependent variable. So,

Table 7 and

Table 8 display the outcomes of OLS regressions to further explore the relationship and understand which specific groups differ from each other. Across all regression models, we employ the corresponding compliance rate as the dependent variable. The results are robust across specifications and consistent with the previous analysis. Our dataset comprises 300 observations, drawn from 100 participants across three different stages.

Regressions encompasses the compliance rate alongside several control variables as independent predictors. Additionally, we included categorical variables related to the company’s assets, as well as a binary variable reflecting investment choices—specifically whether entrepreneurs opted for investments in the stock market or in a bank. The “sector” variable encompasses various specific sectors, including Tourism, Manufacturing, Trade, Construction, and Other Services. Furthermore, our model incorporates a ‘legal status’ variable, indicating the legal form of the company, encompassing options such as Freelancer, Limited Liability Company, General Partnership, Limited Partnership, Société Anonyme, and others. Lastly, the ‘danger’ variable signifies the business owner’s risk aversion. When applicable, this variable assumes a value of one to indicate risk aversion.

The regression results indicate that gender plays a significant role in compliance behavior. Specifically, the coefficient for gender is positive (0.07) and statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that women tend to be more compliant (

Fortin et al., 2007;

Giese & Hoffmann, 2000;

Pántya et al., 2016), a result that is consistent with previous studies in experimental literature, including

Blaufus et al. (

2017),

Bühren and Kundt (

2014) and

Coricelli et al. (

2010). Compliance decreases significantly at the second stage compared to the first stage. This decline in compliance can be attributed to the increase in the tax rate and the simultaneous decrease in the probability of being audited. This finding suggests that entrepreneurs are more likely to comply with tax obligations when audit probabilities are higher. Further, the size of the company appears to have an impact on compliance behavior. Larger firms tend to be more compliant than smaller ones. This finding implies that the size of a business may influence its willingness to adhere to tax regulations. In addition, General Partnership (GP) and Limited Partnership (LP) companies demonstrate higher levels of compliance compared to freelancers. This result suggests that the legal structure of a business may also be a significant factor influencing compliance. The decision to invest and the sensation of risk appear to have no significant impact on the compliance rate. Together, these data offer insightful information on the variables impacting tax compliance in the study, with legal framework emerging as important factor.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Relevant Literature

Tax compliance has been thoroughly investigated through several methodologies such as field experiments, surveys, and online interaction analyses, bringing to light diverse factors that affect taxpayer behavior (

Onu & Oats, 2016;

Torgler, 2013). This domain could benefit from open government data initiatives and collaborative efforts between scientists and the government or tax administration (

Torgler, 2021). Taxpayer empowerment has a major impact on tax compliance, according to

Casal et al. (

2016) and other studies on compliance tactics.

Casal et al. (

2016), demonstrate that when taxpayers are given a voice in how taxes are distributed and tax information is provided in a broader, non-tax-specific context, compliance rates improve significantly. This suggests that increasing taxpayer engagement and transparency can foster a stronger sense of fairness and ownership, ultimately leading to enhanced voluntary compliance. This highlights the necessity of reducing the social gap that exists between taxpayers and tax authorities. Meanwhile, research by

Vlachos and Bitzenis (

2016) on Greek small businesses shows that tax burden and corruption are important contributors to non-compliance, suggesting that non-compliance should not be interpreted as merely a survival strategy in the face of economic difficulties.

Tax avoidance presents a significant challenge, especially in developing countries where tax revenue collection frequently fails to meet its potential. In response to the intricate issue of tax compliance, researchers have increasingly employed field experiments to evaluate behavioral interventions aimed at both individual taxpayers and corporations. These studies have revealed that strategies such as providing assistance, issuing prompts, delivering feedback, leveraging social norms, implementing deterrents, and sending alerts can markedly enhance compliance rates (

Batrancea et al., 2022;

Hallsworth, 2014). Furthermore, investigations targeting small businesses and entrepreneurs indicate that elements such as trust, education, and tailored deterrence play a vital role in fostering compliance (

Kiconco et al., 2019;

Nagel et al., 2019), while real-world evaluations yield important insights into actual payment behaviors (

Dörrenberg et al., 2022;

Olsen et al., 2018;

Zucco et al., 2020). For instance, research conducted in Argentina (

Castro & Scartascini, 2013) has demonstrated that informing taxpayers about penalties and legal repercussions improves property tax compliance, while findings from Belgium (

De Neve et al., 2021) suggest that clearer communication further enhances compliance rates. Additional studies in the Dominican Republic (

Holz et al., 2023) and Texas (

Belnap et al., 2023) corroborate that messages emphasizing deterrence and increasing the visibility of tax obligations can significantly boost tax revenue. Together, these results highlight the effectiveness of behavioral interventions and the necessity of customizing strategies to fit specific contexts and taxpayer demographics.

In Latvia, the deployment of preemptive emails containing behaviorally informed content directed at non-compliant taxpayers resulted in an increase in timely tax submissions by as much as 9.4% (

Jamison et al., 2021). A related experiment in the Dominican Republic revealed that behavioral nudges contributed to an increase in tax revenue of USD 193 million, primarily by reducing the number of claimed tax exemptions, with larger firms being more significantly affected than smaller businesses and self-employed individuals (

Holz et al., 2020). Additionally, research indicated that messages focusing on the monitoring and enforcement actions of tax authorities were particularly effective in boosting compliance, with generalized costs of non-compliance proving more impactful than specific temporal or cognitive incentives (

Floyd et al., 2022). The effectiveness of nudges to encourage timely submission of annual tax returns among non-employee taxpayers examined by

Widianto et al. (

2024). The experiment demonstrates how digital communication can enhance tax compliance.

Field experiments have also examined the effects of different interventions on tax compliance in specific populations. A study conducted in Norway investigated the role of moral suasion and perceived detection probability in shaping taxpayer behavior. The findings showed that moral appeals influenced intensive compliance, while detection messages had a strong effect on extensive compliance (

Bott et al., 2020). Furthermore, experiments in New Zealand explored the effects of penalties on tax compliance. The findings suggested that penalty information and rates influenced taxpayers’ stated intentions to comply but had limited effects on actual compliance behavior (

Gemmell & Ratto, 2018).

Studies consistently indicate that self-reported income is more prone to under-reporting and manipulation compared to income that is automatically reported by third parties. This is primarily due to the increased opportunity for individuals to conceal or misrepresent their income when they are solely responsible for reporting it. The evidence suggests that focusing on improving compliance among self-reporting taxpayers is crucial for effectively reducing non-compliance rates and promoting a more equitable and efficient tax system (

Kleven et al., 2011;

Slemrod, 2007). For example,

Slemrod (

2004) argues that small firms tend to exhibit behavior more akin to individual taxpayers rather than larger firms. This distinction arises from the fact that small business owners can directly make decisions regarding tax reporting. In contrast, in large firms, tax planning and reporting decisions are typically delegated to tax managers. According to

Hanlon et al. (

2005), the pattern of tax non-compliance among firms, relative to their total income or assets, exhibits a U-shaped curve. Specifically, tax avoidance is more common in small firms, diminishes in medium-sized firms, and subsequently escalates in large firms.

Additionally, several studies of tax compliance take into account a number of factors that influence how SMEs and independent contractors behave. A study from the Netherlands shows that tax training programs help new business owners follow tax rules more effectively, without shortening the lifespan of their businesses. Instead, these programs boost profits by reducing operational costs, highlighting the benefits of targeted training in increasing entrepreneurs’ understanding of and compliance with tax regulations (

Nagel et al., 2019). The study of

Batrancea et al. (

2022) explores the dynamics of power and trust in relation to tax compliance among independent contractors in eleven different nations. This study shows that people’s compliance behaviors are greatly influenced by their cultural and historical backgrounds, especially in post-communist nations. This emphasizes the significance of trusting authorities and exercising power carefully in order to achieve high compliance levels. When the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) is applied to Ugandan small business enterprises’ tax compliance behavior, it becomes evident that social norms and individual attitudes are significant factors in compliance decisions. The application of TRA to tax compliance within the framework of developing nations contributes to our comprehension of the social and psychological foundations of tax behavior (

Kiconco et al., 2019). Additionally, a randomized field experiment involving small businesses in Bulgaria shows that moral appeals and deterrent strategies such as changing audit probabilities can both increase payroll tax compliance. The study highlights the effectiveness of strategies that combine moral persuasion with enforcement, particularly in larger and riskier firms. This provides insights into strategies for improving compliance that are both cost-effective and generally effective (

Dörrenberg et al., 2022). The relationship between emotions and tax compliance is investigated in an experimental survey of Turkish small business owners. The results show that emotional responses have a significant impact on compliance intentions through the enforcement capacity and trust in tax authorities. According to this research, a well-rounded strategy that incorporates both enforcement and trust-building initiatives can lessen unfavorable feelings and encourage a base of compliant taxpayers (

Olsen et al., 2018). A field study in Rio de Janeiro targeting informal entrepreneurs demonstrated that direct training and support enhanced their knowledge, intentions to formalize their businesses, actual formalization rates, and subsequent adherence to tax obligations (

Zucco et al., 2020).

Last but not least, the review of

Mohamad et al. (

2022) underscores that tax awareness is fundamental to achieving compliance, revealing that this awareness is primarily shaped by tax knowledge, attitude, tax morale, and socialization. Consequently, the findings advocate for targeted educational initiatives and policy interventions by governments and key stakeholders to enhance tax awareness and, in turn, improve compliance rates.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Experimental Design

In this section, we describe the experimental setup, the participant recruitment methods, and the protocol used for the field experiment. Our approach is consistent with previous research efforts in this field (

Choo et al., 2016;

Grundmann & Lambsdorff, 2017). The experiment involved 100 individuals who were invited to take part in the experimental procedure. The eligibility of participants was assessed based on two criteria: first, they had to be residents of Greece, and second, they had to engage in a primary business activity within country or serve as members of a company’s board of directors. We considered each participant’s involvement in each round as an independent entity in our three-round experimental design. We carefully examined responses and behaviors at various phases of the experiment thanks to this approach. As a result, our dataset consists of 300 observations, which represent the total number of participation cases throughout all rounds. This methodological choice offers us a more detailed understanding of participant dynamics inside our experimental framework by making it easier to identify patterns, trends, and behavioral changes that could happen from one round to the next. Treating each experiment round as a discrete event is valid because participants may make different choices based on evolving conditions or new information. Each individual’s unique experiences, convictions, and values can lead to varied responses, even under similar conditions. Recognizing this individuality enhances the understanding of behavior and decision-making. Factors such as fatigue, strategy changes, learning effects, or new experimental settings contribute to this variability. In a 3 × 3 factorial design, examining the effects and interactions of independent factors (tax rates and audit probabilities) on compliance behavior requires analyzing each round independently. This approach captures behavioral changes across different contexts (

Alm & Kasper, 2023;

Torres et al., 2022). All participants attended the annual entrepreneur festival and it is important to note that their decisions during the experiment were driven by genuine motivations, with no deception or manipulation.

A replicated measurement design was implemented, with tax compliance serving as the dependent variable. The experimental design consisted of two distinct parts. The first part focused on addressing the primary research question and involved economic decisions that carried implications for the payment of participants. Our research was funded by Hellenic Open University (HOU). The second part comprised a series of questionnaires aimed at gathering information on business characteristics, personality traits, and the risk preferences of the owners. By employing this two-part approach, we aimed to investigate the relationship between the experimental treatments and tax compliance while also gathering supplementary data on relevant factors that could potentially influence tax behavior. We employed the non-parametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test in our research, which offered us enhanced flexibility by not requiring the data to conform to a specific distribution, such as the normal distribution. This test also makes it easier to compare two empirical distributions and determine whether or not they come from the same distributional framework. We employed an approach in our experiment whereby several treatment groups receive different treatments with varied parameters (e.g., tax rates and hypothetical audit probability). We could examine how these variables affect tax compliance behavior and how they interact with each other in the experimental scenario by varying both the tax rates and the audit probabilities.

In the formulation of our experimental design, we meticulously selected treatment combinations that encapsulate a spectrum of realistic tax environments while remaining anchored in both theoretical frameworks and practical realities. The tax rates of 5%, 25%, and 47% were deliberately chosen to exemplify low-, moderate-, and high-tax scenarios, respectively. The low tax rate (5%) represents a context in which the costs associated with tax evasion are minimal, while the high tax rate (47%) reflects situations where substantial financial incentives exist for underreporting, aligning with the predictions established by the

Allingham and Sandmo (

1972) model. The intermediate rate (25%) functions as a reference point for average tax conditions. In a similar vein, we selected audit probabilities to assess their impact on compliance behavior. A 10% audit probability was introduced to represent a scenario with a heightened perception of detection risk, in contrast to a 5% probability, which signifies a lower-risk environment. Furthermore, an ‘unknown’ audit probability condition was incorporated to mimic the uncertainty inherent in actual tax systems, where taxpayers frequently lack accurate information regarding the likelihood of being audited. This methodology enables us to explore how the distinction between certainty and ambiguity in audit risk affects compliance behavior. So, these are the following combinations:

T5: Represents a tax rate of 5% and is combined with an audit probability of 10% (P10).

T47: Corresponds to a tax rate of 47% and is associated with an audit probability of 5% (P5).

T25: Signifies a tax rate of 25% and is coupled with an unknown audit probability (UP).

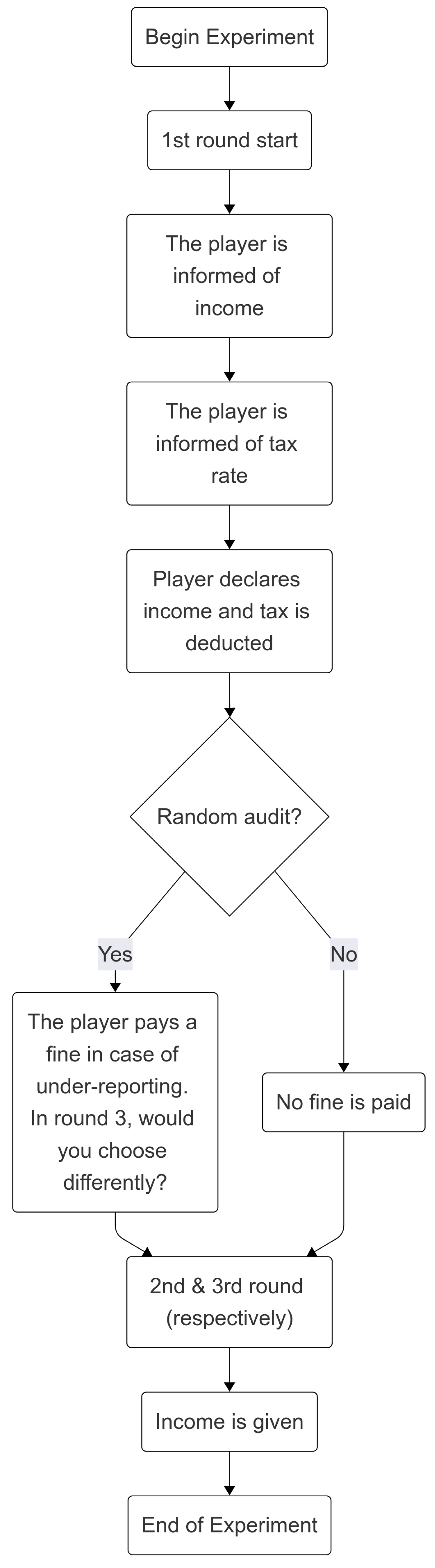

Using a 3 × 3 factorial design, we present a dynamic experimental technique where various treatment scenarios are subjected to changing tax rates and audit probabilities. Understanding how these factors interact in an experimental setting and affect tax compliance behavior is the aim of this study. We want to uncover the complex influences that tax rates (Low, Medium, High) and audit probability (Low, High, Unspecified) have on how individuals make compliance decisions by systematically changing these variables. An efficient method for analyzing the effects of two independent variables and their interactions on a dependent variable is the 3 × 3 factorial design. The primary independent factors in our analysis are the likelihood of an audit and tax rates. The dependent factor is compliance rate. We defined compliance as the ratio of declared income to actual income. For each participant, actual income refers to the fixed income provided at the start of the experiment, while declared income is the amount reported on the tax return during the experiment. The compliance rate is calculated by dividing the declared income by the actual income, with a rate of one indicating full compliance. In instances where the declared income is less than the actual income, the compliance rate is less than one, thereby quantifying the degree of under-reporting. This explicit operationalization allows us to directly measure tax compliance behavior and compare it across different experimental treatments. The overall procedure is described in

Appendix A,

Appendix B and

Appendix C.

We examined the influence of different attributes on the behavior of business owners regarding compliance rates, declared income, and tax obligations. Our extensive experimental framework produced valuable findings that can inform policy-making related to tax rates and the likelihood of audits, thereby enhancing strategies for improving tax compliance.

To quantitatively analyze these associations, we represent the compliance rate as follows:

| Ratio of declared to actual income for the ith company owner. |

| Intercept of the model. |

| Dummy for owner’s gender (1 = female, 0 = male). |

| Industry sector in which the company operates. |

| Legal form of the company (e.g., self-employed, partnership, corporate entity). |

| Owner’s investment behavior, reflecting tax-planning choices. |

| Company size as measured by total assets (proxy for financial capacity). |

| Owner’s perception of business-environment risk (risk aversion). |

| Error term capturing unobserved factors affecting compliance. |

This model specification allows for the differentiation of the effects of individual characteristics on tax compliance. The estimated coefficients yield empirical evidence regarding the influence of factors such as gender, company size, and legal status on compliance behavior, thus informing policy recommendations aimed at improving tax compliance in difficult fiscal contexts.

In addition, we used a three-phase field experiment that aims to capture individual behavioral responses under different tax rates and control probabilities. For data analysis, we chose ordinary least squares (OLS) regression as our primary analytical method for several compelling reasons. It effectively models the linear relationship between the dependent variable (tax compliance rate) and various explanatory factors (such as gender, legal status, investment behavior, assets, and risk perception), which is crucial given the complex and diverse nature of individual behavioral data. Second, it provides coefficients that are simple to interpret, allowing us to quantify the marginal effects of each variable and clearly articulate their influence on tax compliance. It is computationally efficient and is commonly used in similar behavioral research, which helps to draw comparisons with previous studies. To create a thorough analytical framework, this regression analysis is supplemented with the application of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). We were able to thoroughly evaluate the relevance of the complex interactions that exist between tax compliance rates and numerous influencing factors under a variety of experimental situations thanks to this dual-method approach. Further, this approcah enabled us to test the overall impact of categorical factors and their interactions on tax compliance, providing a complementary perspective to the OLS estimates.

In considering the fine level of non-compliant behavior, we propose measuring it as the difference between the expected declared income and the actual declared income (A–D). This approach allows us to assess the extent to which individuals deviate from their expected income reporting and provides an indicator of non-compliant behavior in our experiment. By comparing the expected and actual declared income, we could evaluate the degree of tax avoidance or under-reporting among participants. The experiment comprised three distinct stages: income declaration, audit, and payment generation, each of which involved specific tasks and procedures and are explained in more detail below. By dividing the experiment into these three stages, we sought to examine the impact of different factors on participants’ behavior and the resulting payment outcomes. Finally, by analyzing participants’ compliance decisions and subsequent payment outcomes, we aimed to gain a deeper understanding of how three treatment variables interacted and influenced participants’ behavior in the experiment as depicted in

Table 9. This approach enabled us to investigate the complex dynamics of tax compliance and shed light on the factors that shape individuals’ decision-making in tax-related contexts.

3.2.2. Subject Recruitment and Research Questions Analysis

For this field experiment, entrepreneurs were recruited by random selection during a specific two-hour period each day, coinciding with the attendance of fair visitors. To minimize self-selection bias, the initial instructions provided to participants did not explicitly disclose that the experiment pertained to taxes. Once the experiment was completed, individuals received an informational message reiterating that their choices would remain completely anonymous, and the funding source was clarified. None of the participants utilized the option to drop out of the survey.

During the decision-making process, where choices were immediately influenced by the avoidance decision, subjects were not actively monitored. We made it clear to potential participants during the recruitment phase that they would not be meeting the experimenter in person for payment. Instead, they would contact an intermediary to facilitate individual payments. This approach was designed to eliminate the possibility of potential humiliation from facing the experimenter if they violated the honesty rule. Consequently, if altering the form of participation led to any bias in compliance, it was expected to result in reduced compliance due to increased social distance.

According to the existing research on taxpayer compliance, this section presents predictions and hypotheses regarding the anticipated behavior of the subjects that form the basis of our experiment. The widely accepted examination of tax compliance is based on the models proposed by

Allingham and Sandmo (

1972) as well as

Yitzhaki (

1974). These models depict a taxpayer who must decide on the amount of income to report to the tax authority. It is commonly assumed that an increase in the audit probability results in greater compliance, thus establishing our initial premise. Consequently, we proceed by formulating five assumptions concerning the behavior of the subjects:

RQ 1: How do high tax rates, audit probabilities, and higher fines influence tax compliance?

The presence of a high tax threshold provides greater opportunities for participants to modify their behavior compared to a low tax threshold. Furthermore, aside from undisclosed variations within the absolute range, relative tax levels can also influence tax compliance. We make the assumption that taxpayers tend to move towards higher tax rates, resulting in lower levels of tax compliance. Within this context, taxpayers are usually unaware of the true likelihood of an audit, and tax administrations generally do not disclose their planned audits to the public. Consequently, taxpayers make decisions regarding tax avoidance under conditions of uncertainty rather than clear risk. According to the ambiguity aversion model proposed by

Chateauneuf et al. (

2007), ambiguity leads taxpayers to consider both the best and worst possible outcomes, such as being audited with a probability of zero or one, respectively. Current research and experimental evidence from

Andreoni et al. (

1998);

Alm et al. (

1992) suggests that increasing the penalty for non-compliance likely leads to higher levels of compliance. The uncertainty of audits and the deterrent effect of increased fines are highlighted by recent research. When taxpayers believe there is a greater chance they will be audited and subject to large financial penalties, they are more likely to cooperate. Behavioral economics studies, such those by

Chetty and Finkelstein (

2020), have demonstrated that people are aware of the possible costs and hazards of non-compliance.

RQ 2: How do gender differences and the size of an entity affect tax compliance behavior?

Research evidence has explored the influence of gender on tax compliance behavior among individuals. According to

Frey and Torgler (

2007), women tend to exhibit significantly higher levels of tax compliance compared to men. This finding is supported by related evidence derived from both field studies (

Bühren & Kundt, 2014;

Pántya et al., 2016) and laboratory experiments (

Blaufus et al., 2017;

Coricelli et al., 2010). Comprehending tax compliance is further complicated by the correlation between an individual’s total assets and their tax behavior. One’s asset size can affect their tax behavior in a number of ways. Higher asset levels confer a greater ability for individuals and legal entities to engage in complex tax planning strategies. A larger level of total assets in some situations may signify a stronger capacity to engage in tax planning tactics or to benefit from tax advantages and deductions, perhaps leading to lower tax liabilities. Large assets may offer legal organizations greater options for tax planning and financial management.

RQ 3: How does the legal status influence the tax compliance and behavior of a company?

Analyzing compliance rates for different corporate legal regimes can be challenging, as it requires access to comprehensive and up-to-date data on compliance across different entities. In addition, compliance rates can vary significantly based on factors such as industry, jurisdiction, company size, and specific regulatory requirements.

3.2.3. Content Analysis

In the experiment, participants were provided with a hypothetical annual turnover and were tasked with completing a tax return based on this given turnover. They were required to consider a specific tax rate and the probability of an audit for the corresponding tax year when filling out the tax return. To streamline the process and minimize potential biases, an Access database was utilized. This database automatically calculated the participants’ payments without any human intervention. This approach ensured that the payment calculations were objective and consistent across all participants. Throughout the experiment, the currency used for calculations and payments was Euro (€), which is the official currency of the European Union and Greece. By employing this standardized and automated process, we aimed to eliminate any potential biases that could arise from manual calculations and ensure the accuracy and fairness of the payment calculations for all participants. A period in the experiment consisted of three following rounds below and there were 3 periods in total. The individual stages are as follows.

- Stage 1:

Income declaration

During this stage of the experiment, participants were provided with information about their income, which remained constant throughout all rounds. They were then tasked with reporting their income based on different combinations of tax rate and audit probability for that round. The purpose of this stage was to examine how participants’ income reporting behavior was influenced by different combinations of tax rates and audit probabilities. By manipulating these factors, we aimed to gain insights into the impact of tax policy and enforcement measures on individuals’ compliance decisions.

- Stage 2:

Audit Probability

In this stage of the experiment, participants were subjected to audits with probability, denoted as P, which varied in each round. If a participant’s tax return was selected for an audit and they declared their taxable income honestly, no penalty was imposed on them. However, if they were audited and found to have misrepresented their income, a penalty was applied. The penalty amount was determined as the difference between the participant’s actual income and the income they declared on their tax return. By incorporating the auditing stage into the experiment, we aimed to examine the impact of audits on participants’ compliance behavior and their willingness to accurately report their income. The potential penalties served as a deterrent to tax avoidance and provided an additional incentive for participants to declare their taxable income honestly.

- Stage 3:

Payments

During this stage of the experiment, participants were informed about their payment, which varied from person to person. The payment amount was determined based on the tax morale demonstrated by each participant throughout the previous stages of the experiment. Specifically, the payment was calculated based on their declared income, tax rates, audit outcomes, and overall compliance behavior. Participants who adhered to tax regulations and displayed a higher tax morale were rewarded with a payment reflecting their compliance. Conversely, participants who engaged in non-compliant behavior or tax avoidance faced potential penalties and consequently received lower payment. By linking participants’ payments to their tax morale, we aimed to study the impact of individual compliance behavior on financial outcomes. The overall experimental procedure is depicted in

Figure 6.

4. Discussion and Recommendations

This study investigates various factors influencing tax compliance among Greek company owners, with a focus on gender, company size, and legal status. It takes into account the unique economic and cultural environment of Greece, addressing identified gaps in the literature. In this challenging national context, marked by economic crisis and recovery, our research aims to contribute to both academic discussions on tax compliance and the formulation of policies that are sensitively aligned with the nuances of gender and socioeconomic factors. By conducting a comprehensive field experiment focused on exploring the dynamics of tax avoidance among entrepreneurs, especially within the unique setting of Greece, we try to understand the interplay between tax rate levels and audit probabilities and their collective impact on tax compliance among Greek entrepreneurs. In particular, our study offers an empirical analysis of the thought processes Greek business owners use to support tax compliance.

Recent research has highlighted that tax compliance is influenced not only by individual cost–benefit analyses but also by wider cultural and policy frameworks. For instance, the concept of tax culture—which includes collective perceptions of fairness, trust in governmental institutions, and prevailing social norms—significantly impacts taxpayer behavior. Furthermore, the structure of taxation policy, through its implementation of incentives and penalties, has a direct effect on compliance rates. Ongoing challenges related to tax evasion expose systemic issues that hinder effective tax administration. In addition, tax literacy, defined as the extent to which taxpayers understand their legal and tax obligations, plays a vital role in shaping behavior, providing individuals with the necessary skills to navigate complicated tax systems. This research provides important insights into the intricacies of tax compliance by thoroughly exploring how gender differences and risk perceptions, together with the legal status and cultural-economic elements unique to Greece, impact tax compliance behaviors. The results not only support earlier research that found gender to be a key determinant in tax compliance, but they also broaden our knowledge by emphasizing the particular difficulties small company owners have while negotiating tax laws and reflects our understanding of how these factors collectively influence overall compliance.

In particular, our research reveals that the average compliance rates vary across different rounds and genders, with female participants generally showing higher compliance. Women demonstrate higher tax compliance rates than men, and this difference is further pronounced under conditions of increased audit probability. The gender disparities in self-employed tax compliance habits among Greek business owners as examined in this study reveal that males have lower compliance rates than females. This is consistent with other research (

Blaufus et al., 2017;

Bühren & Kundt, 2014) that found substantial gender differences in tax compliance behaviors (

Coricelli et al., 2010;

Fortin et al., 2007;

Pántya et al., 2016). One potential explanation could be that female entrepreneurs tend to exhibit higher levels of risk aversion compared to their male counterparts who may lean more towards risk-loving behavior.

Moreover, correlation analysis reveals significant relationships between compliance rate and variables such as legal status, assets, and danger (risk aversion). In particular, the legal status of business is significant because various legal entities have distinct tax duties and compliance requirements. We also find significant differences between a company’s size and its tax behavior. That is, the fewer assets a company has, the lower its degree of tax compliance. As suggested in

Thatcher et al. (

2016), small firms encounter difficulties in comprehending and complying with tax regulations because of their low resources and lack of expertise. Furthermore, as suggested by

Kamleitner et al. (

2012), small business owners have a different perspective on tax compliance than do workers. This is mostly because they are better at spotting non-compliance chances, are less concerned about taxes, and see taxes as possible losses. In a time of economic challenges within the Greek context, similar findings were reported in the study by

Lois et al. (

2019), which investigated tax compliance characteristics of the general public in Greece. The study found low compliance levels, linked to specific national traits and the perceived insufficiency of returns from state taxation.

This study also examines the relationship between audit fines and the uncertain probability of regulatory inspection, emphasizing how it affects entrepreneurs’ compliance practices. Increasing the known audit probability significantly improves compliance rates. The uncertainty about audit probability also significantly affects compliance behavior, indicating the importance of perceived audit risks on tax compliance. Contrary to expectations, an increase in tax rates leads to a decrease in compliance, indicating that higher taxes might discourage honest income reporting. Doubling the fine for non-compliance under ambiguous audit conditions leads to a significant increase in mean compliance. Our results are consistent with those of

Yoon et al. (

2011) and

Dubin (

2007), suggesting that increased fines for non-compliance might encourage compliance.

Snow and Warren (

2005) cautioned that this could not be true for all taxpayers, as some may see a decrease in compliance and an increase in uncertainty. Furthermore, as noted by

Livernois and McKenna (

1999), there is a complex relationship between compliance and higher fines. Consistent with the findings of

Kaplanoglou and Rapanos (

2015), compliance behavior is shaped by the authority of tax officials and the perceived risks of audits. Trust in authorities enhances voluntary compliance, whereas increased fines and higher audit probabilities boost enforced compliance.

Moreover, our experimental framework enables us to examine the influence of critical factors on tax compliance in a controlled environment; however, we recognize that such conditions do not fully replicate the complexities of real-world tax administration. In reality, taxpayer behavior is often shaped by tangible financial repercussions, which are not present in our study. For example, the phenomenon of hypothetical bias may result in participants acting differently when there are no real financial stakes involved, while social desirability bias could lead to inflated reports of compliance in a controlled context. To address these issues, we juxtapose our findings with existing field studies (

Hallsworth et al., 2017;

Kleven et al., 2011;

Slemrod, 2007) and observe that, although the directional relationships remain stable, the intensity of the effects might vary in actual tax scenarios. These observations emphasize the necessity for careful interpretation and indicate that our results primarily illuminate the relative significance of different determinants rather than offering precise quantitative assessments of real-world behavior. Future investigations should aim to validate these findings in more naturalistic contexts to enhance our understanding of their implications for policy.

Combining the proposed policies from the literature with the results of this study, our research opens the door to the creation of more focused, efficient tax compliance plans and regulations by providing insight into these complex behaviors. This approach is necessary to enhance tax compliance among Greek businesses, ultimately supporting the broader goals of tax justice and effective tax administration. Based on our findings, we recommend additional policies aimed at enhancing tax compliance. Such policies should support personalizing education and awareness campaigns to emphasize gender-specific attitudes and compliance practices. It is advised to tax authorities to enhance audit transparency by making information regarding audit frequencies and procedures readily available to the public. This approach is likely to improve taxpayer perceptions of enforcement, which in turn may lead to increased compliance. In addition, we suggest that the structure of fines be revised to ensure that penalties for non-compliance are both adequately deterrent and commensurate with the severity of the evasion. For taxpayers, particularly those operating small businesses, we recommend initiatives aimed at improving tax literacy and offering customized assistance to help them navigate the complexities of compliance.

At the international level, our findings advocate for the establishment of a unified fiscal framework in direct taxation. Such a framework would enable coordinated tax policies among nations, especially within the European Union, thereby fostering greater harmonization of tax enforcement and minimizing opportunities for cross-border tax avoidance.

Real-World Implications and Potential Biases

In this part, we explicitly address the practical implications of our experimental results while also recognizing the limitations inherent in utilizing hypothetical scenarios. Our findings reveal that enhancing the perceived likelihood of an audit significantly boosts tax compliance. This observation aligns with existing literature from field studies (

Kleven et al., 2011;

Slemrod, 2007) and implies that implementing more visible and frequent audit practices could effectively increase compliance rates in real-world settings. Furthermore, the identified gender disparities in compliance behavior suggest that tax authorities might benefit from customizing their communication and enforcement strategies to cater to various demographic segments. For example, the elevated compliance rates observed among female business owners may indicate a higher level of risk aversion, implying that targeted policies could harness these behavioral characteristics to promote overall compliance. We acknowledge that the controlled, hypothetical tax scenarios utilized in our study may not entirely reflect the intricacies of actual tax behavior. The decisions made by participants in a simulated context can be swayed by factors such as social desirability or hypothetical bias, which may not be as pronounced when real financial stakes are at play. Additionally, while our experimental framework enables us to isolate the impacts of differing tax rates and audit probabilities, the lack of real financial repercussions constrains the external validity of our conclusions.

5. Conclusions

The field of tax compliance experiments has provided valuable insights into various aspects of tax behavior, such as audits, penalties, and tax rates. While these traditional issues have received much attention, there are still many other areas that could benefit from further exploration and development. In our study, we directly contribute to the existing literature by conducting a randomized field experiment focusing on the role of the tax rate combined with controllability in the tax compliance of SMEs in the Greek economy. By conducting this experiment in a real-world setting, we provide empirical evidence and established a direct relationship between tax rates and the likelihood of audit. The findings indicate that a broader absolute tax range correlates with lower tax compliance levels. When the probability of an audit is uncertain, there is a notable shift in average compliance, contrasting with situations where the audit probability is clear. Additionally, doubling the fines for non-compliance under uncertain audit conditions leads to a significant increase in average compliance across genders. The analysis further reveals that women are more likely to comply with tax regulations than men, with their compliance rate increasing when the audit probability is doubled. A discernible cause-and-effect relationship between tax avoidance and company size is identified, with smaller firms more inclined towards tax avoidance. It was also observed that self-employed individuals exhibit lower compliance levels, underscoring the varied influences on tax compliance across different professional groups.

Recognizing the paramount importance of transparency in audit frequencies and the strategic adjustment of fines for non-compliance, our findings advocate for a dual approach that not only deters tax avoidance but also fortifies public trust in the tax administration system. Furthermore, the study accentuates the urgency of streamlining tax processes for the self-employed and offering unambiguous support to businesses across various legal frameworks, thereby easing the compliance burden. For small businesses, which face their own set of challenges, we suggest a suite of policies including simplified filing procedures, tax education, and incentives for maintaining compliance. Additionally, our recommendations extend to rewarding honest income reporting through tangible benefits such as tax discounts, credits, or public accolades, thereby fostering a culture of integrity within the business community. This holistic approach not only aims to curtail tax avoidance but also aligns with the broader objectives of ensuring tax justice and enhancing the efficacy of tax administration in Greece.

This research provides an in-depth examination of the factors influencing tax compliance within a complex fiscal landscape, successfully connecting experimental results to practical policy ramifications. Additionally, our analysis emphasizes the significance of the Greek context for the broader European Union. We contend that Greece, characterized by its distinct fiscal and cultural obstacles, can act as a reference point for comprehending compliance behaviors in other nations encountering analogous challenges. While tax compliance and evasion may be viewed as immediate reactions to policy incentives and enforcement strategies, our results highlight that tax culture—formed by societal perceptions, trust in governmental institutions, and prevailing norms—plays an essential role in shaping these behaviors.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study effectively achieved its goals, it is important to recognize the inherent limitations of its methodology, particularly the use of a sample of entrepreneurs who responded to a hypothetical tax scenario. Due to our research objectives and the imperative need for maintaining experimental rigor, we found it necessary to introduce certain assumptions that may not universally align with real-world decision-making scenarios. In the future, research will aim to include scenarios that better reflect the settings and conditions that prevailed during the pertinent period of time.

Moreover, one potential limitation is the uncertainty regarding whether hypothetical scenarios accurately reflect real-life tax behavior. In this study, participants were given instructions on how to approach a hypothetical tax situation and were subsequently queried about their compliance. This process may have made the intervention transparent to participants, potentially introducing response bias due to demand characteristics. Additionally, the compliance measure focused solely on hypothetical scenarios and captured only basic intentions. It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations in terms of external validity and generalizability. The application of a hypothetical tax scenario may limit the external validity of our results. Responses from participants in a simulated context, devoid of actual financial repercussions, might be swayed by social desirability or hypothetical bias, which could lead to discrepancies between their behavior in this controlled environment and their actions in real-world situations.

Furthermore, we purposefully included some ambiguity in our experimental design. Participants were given the chance to act dishonestly while being expressly told to declare their whole income. This purposeful ambiguity was introduced to create a conflict between the desire to maximize financial gain and the preference for following tax laws. Noting that governments frequently stress the need of compliance even in the lack of clear financial incentives to do so, it is important to note that such ambiguity is not wholly unfamiliar to real-world tax systems. As acknowledged by other studies, using laboratory samples poses challenges in generalizing the findings to real-world contexts. The main concern is the lack of evidence demonstrating a direct correlation between tax attitudes and actual tax reporting behavior (

Hessing et al., 1993).

Considering the limitations this study experienced, we acknowledge the significance of improving our methods and addressing these issues in future investigations. Future research includes a thorough analysis of potential modifications and enhancements to our approaches. In addition, future research should replicate the experimental design while also examining the behavior of entrepreneurs after randomized audits, similar to the evaluative surveys conducted by

Slemrod (

2001) and

Kleven et al. (

2011) but using a different sample. This exploration would provide valuable insights and is an area left for future investigation.

Author Contributions

S.V.A. and D.K.T. jointly conceived and designed the study. S.V.A. developed the methodology, implemented the software, conducted the formal analyses and investigation, curated the data, and produced all visualizations; both authors collaborated on writing the original manuscript. S.V.A. and D.K.T. validated the results. D.K.T. administered and oversaw the project, supervised its progress, and additionally reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it involved non-invasive expert elicitation and did not include the collection of personal or sensitive data, in accordance with the provisions of Greek Law 4521/2018 and Article 6 of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679. In addition, the study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Hellenic Open University, confirming that it complied with the relevant ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Hellenic Open University for its financial support, which made this research possible. Additionally, we appreciate the institution’s commitment to fostering academic excellence and providing a supportive research environment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Guides of Participants

Dear Participant,

Thank you for participating. Furthermore, we would like to briefly describe the objective of this research. The purpose of the study was to understand the factors that influence taxpayers’ decisions about how much to pay in taxes. This was achieved by having the participants calculate their pre-tax income. We then determined the percentage of pre-tax income reported by participants to assess tax compliance. This study aimed to improve understanding of taxpayer behavior by examining the impact of various audit rates on tax compliance. We wish to inform you that all of your data are completely anonymous and that there is no way for your identity to be associated with any of your experiment responses. Hellenic Open University researchers follow rigorous moral standards, which include protecting participants’ privacy. The organizers will only receive anonymized data from the experiment, meaning that no names or other identifying information will be offered. They do not have access to any personal data related to this study. We are going to publish the study findings in journal articles and reports. These publications will contain aggregated information such as the average compliance rate for each study participant. The results of individual participants will never be made public. We will immediately remove your information from the project if you decide not to participate in the study.

Appendix B. Guidelines and Procedures

Appendix B.1. Verbal Guidelines (Interpreted from Greek)

Welcome to the experiment!

I will now present the following general guidelines before commencing the experiment. Please carefully attend to these instructions and refrain from clicking the “Start Experiment” button until they have been fully explained. The aim of this experiment is to gain a better understanding of human behavior. This experiment provides an opportunity to earn money, with the amount ranging from 0 to 10 Euros, contingent on your choices. All participants in this experiment will remain anonymous. Furthermore, the payments will be transmitted securely, ensuring that no other participants in the group will have access to this information. The specific amount of money you will receive is only known to the experimenters. Subsequent instructions will provide a comprehensive overview of the experiment. Please thoroughly review all the details before proceeding to the next screen with a mouse click, as once you leave these instructions, you will not be able to return to them. If you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to raise your hand.

You may now proceed by clicking the “Start Experiment” button.

Appendix B.2. Instructions on the First Screen (All Treatments)

We thank you for your participation in this study. Please take a moment to carefully read and understand the provided instructions. At the end of these instructions, there will be some comprehension questions, and if you can answer them correctly, you will have the opportunity to earn money. The experiment consists of three rounds, and in each round, you will engage with an imaginary scenario and receive payment accordingly. Your objective in every round is to immerse yourself in different situations and respond truthfully. Each round will last between thirty and sixty seconds, and you will be notified of the specific time limit just before the start of each round. While you are actively participating, the remaining time will always be displayed in the upper right corner of the screen. If you have comprehended these instructions, please press “continue” button. Taxes must be paid on the money won on each round. You will need to complete a tax return for each job after completion. The tax rate you will pay on your income in each round will be shown. Your income for the respective round will be reduced by the applicable tax charge. ‘After the tax deduction, your income will be X euros here’. X depends on the rate of import taxes. For each round in which your supposed income is completed, you will receive five euros.

Click the button ‘continue’ if you think you understand these instructions.

Finally, at the conclusion of the experiment, you will receive payment.

Your payout amount is computed as follows:

Appendix C. Profile Questions

Q5. Annual turnover of your business:

a. >500,000 €

b. EUR 500,000 –EUR 1,000,000

c. EUR 1,000,001 –EUR 5,000,000

d. EUR 5,000,001 –EUR 10,000,000

e. >EUR 10,000,000

Q6. Judging from the other companies in your industry, you would say that:

a. Greek companies avoid taxes

b. Greek companies do not avoid taxes

Q7. If you had to choose between a secure investment with (a) a low but certain return (Bank) or (b) an investment with a potentially high but uncertain return (Stock Exchange) you would:

a. Deposit your money with the Bank to ensure that you receive a fixed amount (interest) without risking the initial capital

b. Buy shares on the stock exchange (so that you have the possibility of earning much larger amounts even if you risk losing the initial capital)

| Start of the experimental procedure: |

Your company has a profit of EUR 50,000, the tax rate is 5%, and the probability of an audit by the tax authorities is 10%.

1. What amount of profit would you declare to the tax authorities considering the tax rate and the possibility of an audit:

2. Based on the reduction of the tax rate (5%), your available profits are:

Your company has a profit of EUR 50,000, the tax rate is 47%, and the probability of an audit by the tax authorities is 5%.

1. What amount of profit would you declare to the tax authorities considering the tax rate and the possibility of an audit:

2. Based on the reduction of the tax rate (47%) your available profits are:

Your company has a profit of EUR 50,000, the tax rate is 25%, and the probability of an audit by the tax authorities is unknown.

1. What amount of profit would you declare to the tax authorities considering the tax rate and the possibility of an audit:

2. Based on the reduction of the tax rate (25%), your available profits are:

References

- Allingham, M. G., Sandmo, A., Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis, Allingham, M. G., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J., & Kasper, M. (2023). Using behavioural economics to understand tax compliance. Economic and Political Studies, 11, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J., McClelland, G. H., & Schulze, W. D. (1992). Why do people pay taxes? Journal of Public Economics, 48, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J., Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Batrancea, L. M., Nichita, A., De Agostini, R., Batista Narcizo, F., Forte, D., de Paiva Neves Mamede, S., Roux-Cesar, A. M., Nedev, B., Vitek, L., Pántya, J., Salamzadeh, A., Nduka, E. K., Kudła, J., Kopyt, M., Pacheco, L., Maldonado, I., Isaga, N., Benk, S., & Budak, T. (2022). A self-employed taxpayer experimental study on trust, power, and tax compliance in eleven countries. Financial Innovation, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, A., Welsch, A., & Williams, B. (2023). Remote tax authority. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 75, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaufus, K., Bob, J., Otto, P. E., & Wolf, N. (2017). The effect of tax privacy on tax compliance—An experimental investigation. European Accounting Review, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, K. M., Cappelen, A. W., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2020). You’ve got mail: A randomized field experiment on tax evasion. Management Science, 66, 2801–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühren, C., & Kundt, T. C. (2014). Does the level of work effort influence tax evasion? Experimental evidence. Review of Economics, 65(2), 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, S., Kogler, C., Mittone, L., & Kirchler, E. (2016). Tax compliance depends on voice of taxpayers. Journal of Economic Psychology, 56, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L., & Scartascini, C. (2013). Tax compliance and enforcement in the pampas. In Evidence from a field experiment (Inter-american development bank working paper series). Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Chateauneuf, A., Eichberger, J., & Grant, S. (2007). Choice under uncertainty with the best and worst in mind: Neo-additive capacities. Journal of Economic Theory, 137, 538–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R., & Finkelstein, A. (2020). Public economics. NBER Reporter, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, C. Y. L., Fonseca, M. A., & Myles, G. D. (2016). Do students behave like real taxpayers in the lab? Evidence from a real effort tax compliance experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 124, 102–114. [Google Scholar]