Abstract

Extreme weather events are the primary driver of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) responsible investment or sustainable stocks, which are gaining popularity worldwide, including in Thailand. Nevertheless, the function of sustainable stocks remains an academic dispute and without satisfactory conclusion for decision-making of Thai investors. Thus, we adopt a dynamic conditional correlation generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (DCC-GARCH) model to examine the influence of Thailand sustainability investment on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. The result indicates that Thailand sustainability investment lacks hedging functions and is classified as a weak safe-haven for consumer product stocks, bitcoin, and Thai baht. Consequently, Thailand sustainability investment provides a better alternative asset for risk diversification, although volatility is low compared to other financial assets and decreases during crises. Investors are advised to diversify their investment risks by adding Thailand sustainability investment to their portfolios during a bearish market.

JEL Classification:

C50; G11; G15; Q56

1. Introduction

The concern about global climate change has driven an interest in sustainability investment. Sustainability investment is investing in companies that comply with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles. Such practice is socially responsible investment or sustainable stocks (Piserà & Chiappini, 2024). After the Paris Agreement in December 2015 to cut carbon emissions and reduce global warming problems, global sustainability investment reached $22.84 trillion in 2016 and is expected to increase to $50 trillion by 2025 (Bloomberg Intelligence, 2022). As a result, major stock markets, such as the Dow Jones, MSCI, and FTSE Russell, have established sustainability indexes. The Thailand Sustainability Investment Index (THSI index) was established in 2015 by consolidating listed companies that comply with ESG principles. The THSI has a market capitalization of up to THB 13.40 trillion (July 2023), which has increased from 2020 when the market capitalization was only THB 9.78 trillion (The Stock Exchange of Thailand, 2023a). Sustainability investment growth results from higher returns and lower risk, especially during crises and economic uncertainty (Naeem & Karim, 2021; Omura et al., 2021). Hence, investing in sustainable stocks can reduce risk in portfolios due to their lack of correlation with other financial assets (Nittayakamolphun et al., 2024a). This conforms to Markowitz’s (1952) portfolio theory, which emphasizes variable asset investment for risk aversion.

Allocation from stock market to sustainable stock may be regarded as costly. Döttling and Kim (2024) stated that, during the economic downturns due to COVID-19, retail investors and mutual fund investors reduced their investment in sustainable stocks. The fact that COVID-19 has driven a need for economic stimulus policy and the energy crisis from the Russia–Ukraine war (Umar et al., 2022) are the causes of inflation. The sustainable stocks comprise only 16% of the THSI in the energy sector (The Stock Exchange of Thailand, 2023b), which is a low proportion of the energy sector and is considered environmentally unfriendly. Therefore, investing in sustainable stocks may face systematic risks during high inflation and recessions (Lei et al., 2023), pursuing the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) by Sharpe (1964). Hence, investors may prefer a safe-haven for risk management or assets that bear higher returns for risk premiums, i.e., gold as a hedge against inflation (Basher & Sadorsky, 2022), crude oil, and clean energy (Iglesias-Casal et al., 2020). In 2022, the return of commodities was 8.71%1, while the return of sustainable stocks was −19.03%2. Likewise, Prinyapon et al. (2022) demonstrated that sustainable stocks pose a higher risk but lower return than the stock markets. This contradicts financial economics theory, which states that there is a positive correlation between returns and risk. Consequently, this question concerns whether sustainable stocks can be hedges, a safe-haven, or diversifiers. Baur and Lucey (2010) demonstrated that assets uncorrelated or negatively correlated with other assets in the portfolio during a bearish market or uncertainty can serve as a safe-haven.

Previous studies about the hedging and safe-haven role of sustainable stocks in other financial assets are limited and unclear. Mousa et al. (2022) indicated sustainable stocks as a safe-haven for stock markets, including gold, crude oil, and bitcoin (Cagli et al., 2023; Nittayakamolphun et al., 2024a). On the one hand, Piserà and Chiappini (2024) concluded that sustainable stocks are not a safe-haven. Andersson et al. (2022) and Nittayakamolphun et al. (2024b) illustrated that sustainable stocks are diversifiers for stock markets, crude oil, currency, and gold. The linkage between foreign sustainable stocks and other financial assets cannot be a sound investment judgement for Thailand. Therefore, it is essential to find a linkage between Thailand’s stock market and financial assets when investing in the THSI. However, the present studies in Thailand have focused on the sustainability of financial performances (see, e.g., Suttipun, 2023; Suttipun et al., 2023) and the relationship between returns and risks of the THSI (see, e.g., Asvathitanont & Tangjitprom, 2020; Prinyapon et al., 2022; Sinlapates & Chancharat, 2022), which may be insufficient for investment decision-making, while the studies on the function of the THSI as hedging or a safe-haven are limited. Hence, in the absence of the THSI’s role as a hedge or safe-haven, this study aims to address the research gap by analyzing the THSI performance on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. The contribution can present perspectives on the THSI performance while also displaying the volatility linkage between the THSI, financial assets, and Thailand’s stock market in every industry for the judgment of retail and mutual fund investors to minimize risk effectively. In addition, the policymakers can support the investment that considers ESG.

2. Literature Review

Investors have become more focused on sustainability over the past decade, leading to large investments in the listed companies that operate in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) or sustainable stocks (Ferriani & Natoli, 2021). Although sustainability is not directly related to a company’s fundamentals, it generates a downside risk and a better performance compared to its non-performing past (Chen & Mussalli, 2020). Investing in sustainable stocks has better risk-adjusted returns than investing in stock markets, as it is an alternative asset class with low risk and volatility (Omura et al., 2021), resulting in motivation of retail and mutual fund investors to shift their portfolios from high-risk financial assets to sustainable stocks (Singh, 2020). While investing in sustainable stocks may lead to the achievement of global sustainability goals, the conclusion as a financial asset, particularly in Thailand, is unclear, which also includes systematic risk and the Black Swan that affects the sentiment of the investors. Therefore, investors must apply portfolio management with a safe-haven and diversify financial assets to minimize risks.

According to the asset classification defined by Baur and Lucey (2010) and Baur and McDermott (2010), at high market volatility, assets that are negatively correlated with other assets in the portfolio are a strong safe-haven, but if uncorrelated, they are a weak safe-haven. Assets with an average negative correlation with other assets in the portfolio are a strong hedge, whereas assets that are uncorrelated are a weak hedge, while assets with a positive correlation are a diversifier. This implementation is popularly applied for gold, crude oil, stock markets, and cryptocurrencies (Nittayakamolphun et al., 2022; Al-Nassar et al., 2023; Naeem et al., 2023).

Previous studies did not reach a consensus on the performance of sustainable stocks in traditional financial assets and cryptocurrencies. Cagli et al. (2023) concluded that sustainable stocks are a safe-haven for gold, crude oil, as well as stock markets (Mousa et al., 2022; Naeem et al., 2023), and bitcoin (Pedini & Severini, 2022; Nittayakamolphun et al., 2024a). On the other hand, Iglesias-Casal et al. (2020) and Lei et al. (2023) clarified that gold is a safe-haven for sustainable stocks. Similarly, Piserà and Chiappini (2024) explained that sustainable stocks are not a safe-haven. Rubbaniy et al. (2022) confirmed that sustainable stocks are a safe-haven during crises, like COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war (Hasan et al., 2023). Umar et al. (2020) found that sustainable stocks are diversifiers for the stock markets, crude oil, as well as gold (Nittayakamolphun et al., 2024b), and bitcoin (Naeem & Karim, 2021). Hence, sustainable stocks act as diversifiers (Andersson et al., 2022), particularly among the emerging markets (Katsampoxakis et al., 2024), which can reduce the downside risk in portfolios (Imran et al., 2024). With limited studies in Thailand, it is insufficient for investors to make better judgements. For this reason, we consider the THSI performance on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets covering Thailand’s stock market in all industries as well as financial assets such as gold, crude oil, and clean energy that suit investors’ interests to focus on sustainability (Iglesias-Casal et al., 2020; Pedini & Severini, 2022), including Thai baht and bitcoin as digital assets, which have experienced significant growth over the past five years.

Ratner and Chiu’s (2013) research, which develops upon Baur and Lucey (2010) and Baur and McDermott (2010), applies dynamic conditional correlation (DCC) derived from the DCC generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (DCC-GARCH) model established by Engle (2002) to explain the dynamic correlation of volatility. The model is suitable for high-frequency and dynamic or co-movement data, such as financial assets, which is popularly used, for example, by Nittayakamolphun et al. (2022), Al-Nassar et al. (2023), and Lei et al. (2023). Thus, we applied the DCC-GARCH model to analyze the DCC between the THSI on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets as well as the performance of the THSI as a hedge or safe-haven for Thailand’s stock market and financial assets.

3. Data and Research Method

3.1. Data

This study examines the performance of the THSI in Thailand’s stock market and financial assets, including stock markets, foreign exchange markets, commodities markets, and digital asset markets (Table 1), considering the convenience of financial asset investment. Due to data access limitations, the daily time series were available for 1207 days, from 2 July 2018 to 30 June 2023. The data sources were acquired from the SETSMART database of the Stock Exchange of Thailand, investing.com, and spglobal.com. Gold and bitcoin are regarded as a safe-haven (Basher & Sadorsky, 2022), whereas crude oil and clean energy are preferred commodities associated with stock markets (Iglesias-Casal et al., 2020) and exchange markets (Lei et al., 2023). Investing in these financial assets could minimize portfolio risk.

Table 1.

Variable definitions.

The data used in this study are comprehensive, with two major shocks: the COVID-19 pandemic (during 30 January 2020 to 23 February 2022), which was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a public health emergency of international concern, and the Russia–Ukraine war (outbreak on 24 February 2022). This study represents the return calculated as , where and are the return and closing price of the THSI, Thailand’s stock market, and financial assets at time t, respectively, and is a natural logarithm that reduces the variance of the time series data.

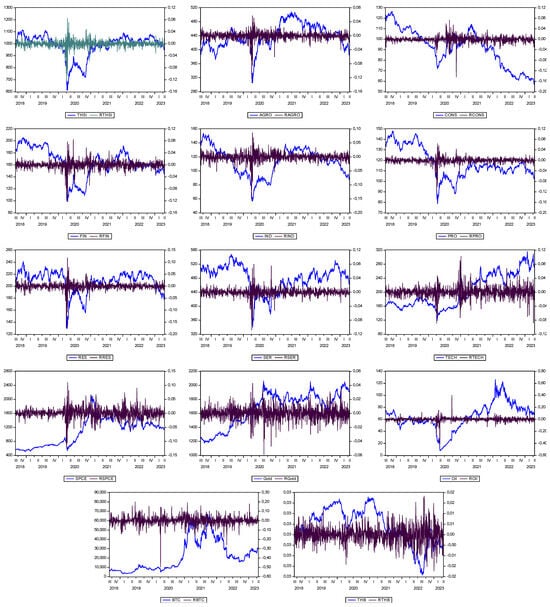

The return series for the THSI, Thailand’s stock market, and financial assets presented that only technology stocks (TECH), clean energy (SPCE), gold (Gold), and bitcoin (BTC) are positive. We observed that bitcoin has the highest average return and risk when considering the standard deviation (S.D.). While crude oil (Oil) is the second highest risk, it has the third lowest average return. In a comparison between returns and risks during this study, there are financial assets with high returns but without high risks, i.e., gold, with a higher average return but lower risk than Thailand’s stock markets, except technology stocks. The return for all series is stationary at 0.01 significance level. Based on the unit root tests of Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP), there is a non-normal distribution, and there is a serial correlation since Jarque-Bera and ARCH were significant, respectively (Table 2). The volatility for all return series is clustered and time-varying (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation.

Figure 1.

Price index and return of the THSI, Thailand’s stock market, and financial assets.

Next, Table 2 shows the correlation between the THSI on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. We found that the THSI on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets had a significant relation in the same direction, except for gold. A major indication of the correlation is that the THSI and Thailand’s stock market have a high correlation, except for consumer products stocks (CONS) and technology stocks. Such pairs of assets are in the same movement and cannot be hedged.

We also used the vector autoregressive model (VAR) to select the optimal lag length with the lowest Schwarz information criterion (SIC) and found that the optimal lag length was zero (Table A1). From the above data, the GARCH(1,1) model is suitable (Harnphattananusorn, 2019) to analyze the DCC through the DCC-GARCH(1,1) model, which will be presented in the next section.

3.2. Research Method

Following Ratner and Chiu’s (2013) method, we analyzed the THSI performance on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. First, the DCC was analyzed with the DCC-GARCH model, and finally, we performed asset classification. The steps are as follows.

The DCC analysis with the DCC-GARCH (Engle, 2002) model explains the multivariate time-varying volatility, which is also suitable for high-frequency and dynamic data. It is feasible for a large correlation matrix, which can be estimated by the GARCH(1,1) model in the first step:

Mean equation:

Variance equation:

where is the residual at time t. is a conditional mean of . The property of is , where is data obtained at time t − 1; is the white noise process; is a conditional variance (volatility of at time t); is the constant; captures the ARCH effect; and captures the GARCH effect.

The second step is to estimate the DCC-GARCH(1,1) model to assume the time-varying conditional covariance (); the equation is as follows:

where is a diagonal matrix of the standard deviation with conditional time-varying of from the GARCH(1,1) model and having a positive property. When is a time-varying conditional correlation symmetrical matrix with standardized residual (), the equation is as follows:

where is a symmetrical matrix with a positive conditional covariance of standardized residual, and is a diagonal matrix of the standard deviation with composition of . The model of DCC-GARCH(1,1) can be written as follows:

where is a symmetrical matrix with a positive unconditional covariance of standardized residual, which is estimated from , where and are parameters in which . The calculation of the DCC is as follows:

where i and j refer to the THSI and Thailand’s stock market or financial assets, respectively.

The hedge and safe-haven analysis of the THSI, according to Ratner and Chiu’s (2013) method, uses a DCC between the THSI and Thailand’s stock market or the THSI and financial assets from the DCC-GARCH model. Dummy variable (D) is determined by extreme movement in the lower 1% (), 5% (), and 10% () in the return distribution of Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. The equation is as follows:

When is a dynamic conditional correlation, is the return of Thailand’s stock market and financial asset j at time t, and is the residual at time t. The coefficient of Equation (8) is according to Baur and Lucey (2010) and Baur and McDermott (2010). The THSI is a strong hedge for Thailand’s stock market and financial asset j if is negative, while it is a weak hedge if zero and a diversifier if positive. The THSI is a strong safe-haven for Thailand’s stock market and financial asset j if , , and are negative or a weak safe-haven if zero and a diversifier if positive when the return movement quantiles are below 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively (see, e.g., Naeem et al., 2023; Lei et al., 2023; Imran et al., 2024).

To analyze the performance of the THSI on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets during COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war, we applied Baur and McDermott’s (2010) method by implementing dummy variables (D) for the two major shocks (Al-Nassar et al., 2023; Nittayakamolphun et al., 2024a). The equation is as follows:

The coefficients of Equations (9) and (10) explained the shock during COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war, respectively. The THSI is a strong hedge for Thailand’s stock market and financial asset j if and are negative, while it would be a weak hedge if zero and a diversifier if positive. Likewise, the THSI is a strong safe-haven for Thailand’s stock market and financial asset j if and are negative or a weak safe-haven if zero and a diversifier if positive.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Dynamic Conditional Correlation Analysis

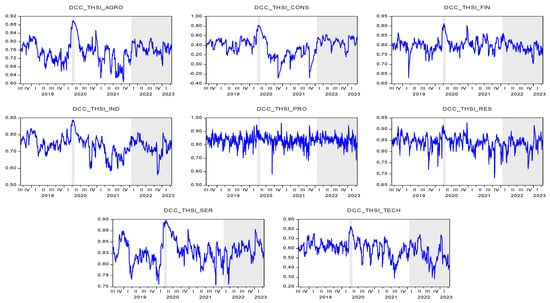

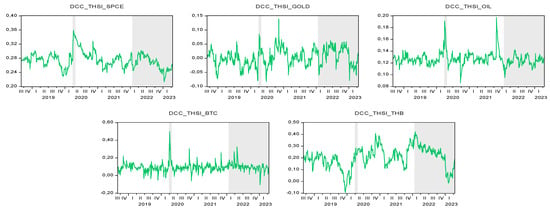

The result of the DCC analysis between the THSI on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets using the DCC-GARCH(1,1) model has no serial correlation because the Q2 statistic is not significant. Thus, it is a suitable model (Table A2). We found that the effect of the previous shock () and the previous DCC () on the current DCC () was significantly in the same direction, except for clean energy (SPCE), crude oil (Oil), and bitcoin (BTC), where the previous shock was insignificant. When considering the DCC in pairs, we found that the THSI has a dynamic correlation with the volatility of Thailand’s stock market and all financial assets in the same direction, with an average of 0.003 to 0.840 (Table 3). The volatility of the THSI will be most positively affected by the volatility of resources stocks (RES) and the lowest volatility of consumer products stocks (CONS) in Thailand’s stock market (Figure 2). The volatility of the THSI will be most positively affected by the volatility of clean energy, and the lowest is gold (Gold), among financial assets (Figure 3). We can state that the THSI may not have direct potential to hedge against Thailand’s stock market and financial assets during this study due to its positive correlation. This is consistent with Umar et al. (2020), Bal and Maharana (2023), and Sharma et al. (2024), who state that investing in sustainable stocks cannot be a hedge but a diversifier.

Table 3.

DCC results.

Figure 2.

Dynamic conditional correlation between the THSI and Thailand’s stock market.

Figure 3.

Dynamic conditional correlation between the THSI and financial assets.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that the volatility of the THSI is mostly affected by the volatility of Thailand’s stock market and financial assets during COVID-19 or March 2020 (Highlight 1) due to a significant increase in correlation. This affects the economy, Thailand’s stock market, financial assets, and investors’ sentiment, resulting in an increase in the THSI portfolio adjustments by investors. In a relaxed situation, the relationship will revert to its original form. During the high geopolitical risk from the Russia–Ukraine war on 24 February 2022 (Highlight 2), the information may indicate that the THSI could be a safe-haven only for the resource stocks, clean energy, gold, and crude oil due to a significant decrease in correlation. Therefore, the THSI is a safe-haven during a crisis or economic downturn. Consistent with Hasan et al. (2023), they concluded that sustainable stocks are a potential safe-haven during the Russia–Ukraine war. Similarly, Rubbaniy et al. (2022) explained that sustainable stocks are a potential safe-haven during COVID-19 and economic crises, such as the European debt crisis and the shale oil crisis (Naeem et al., 2022).

4.2. Hedge and Safe-Haven Analysis

The result from Table 4 shows that the THSI is significant and can be a diversifier for Thailand’s stock market and all financial assets ( > 0) without a hedge. Consistent with Umar et al. (2020), Naeem and Karim (2021), Andersson et al. (2022), and Nittayakamolphun et al. (2024b), sustainable stocks are diversifiers for stock markets, crude oil, gold, bitcoin, and currency. Apart from the concerns on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, investing in the THSI provides a higher return than all stocks in Thailand’s stock market (except the agro and food industry stocks (AGRO) and technology stocks (TECH)) and financial assets (except clean energy, gold, and bitcoin). With a high return, referring to Table 2, investing in the THSI also bears risks at only 8th out of 14th. Similarly, Sinlapates and Chancharat (2022) summarized that investing in the THSI will have a high return and low risk in the long-term. Therefore, the THSI can be a diversifier.

Table 4.

Results of hedge and safe-haven analysis of Thailand’s stock market and financial assets.

The results unveiled that the THSI is a weak safe-haven for Thailand’s stock market and financial assets against extreme movement below the 10% quantile (, , and = 0), except financial stocks (FIN), industrial stocks (IND), and service stocks (SER), for which the THSI is a diversifier against extreme movement below the 5% quantile ( and > 0). The THSI will be a diversifier for agro and food industry stocks, property and construction stocks (PRO), resources stocks, technology stocks, clean energy, gold, and crude oil against extreme movement below the 1% quantile ( > 0) (Table 4). Consistent with Nittayakamolphun et al. (2024a), sustainable stocks are a weak safe-haven for bitcoin, including gold, crude oil, and stock markets (Mousa et al., 2022; Cagli et al., 2023). Nevertheless, amongst all assets, when considering > 0, investing in the THSI can be more of a diversifier than a safe-haven for Thailand’s stock market and financial assets, except for consumer products stocks, bitcoin, and Thai baht (THB). Confirming the findings from Bal and Maharana (2023) and Piserà and Chiappini (2024), sustainable stocks are neither a hedge nor a safe-haven, particularly in the emerging markets (Katsampoxakis et al., 2024). Furthermore, Imran et al. (2024) stated that including sustainable stock in the portfolio can diversify and reduce downside risk.

The result of safe-haven and hedging assets during COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war revealed that the THSI cannot statistically hedge for Thailand’s stock market and all financial assets ( and > 0) except gold due to its weak hedge ( and = 0). The two shocks have impacted the global economy, including Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. Hence, the THSI cannot serve as a hedge. Sustainable stocks are comparable to conventional stocks. Investors perceive sustainable stocks as socially responsible investments with high returns in the long-term and as portfolio diversifiers (Imran et al., 2024) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of hedge and safe-haven analysis of Thailand’s capital market and financial assets during COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war.

The THSI will serve as a strong safe-haven for the agro and food industry stocks, consumer products stocks, and industrial stocks while acting as a weak safe-haven for the property and construction stocks, resources stocks, technology stocks, and bitcoin during the COVID-19 period. Thus, the THSI cannot serve as a hedge, which confirms Figure 2 and Figure 3. The findings in this section support the conclusion that the THSI can serve as a safe-haven during COVID-19 and are consistent with Rubbaniy et al. (2022), Mousa et al. (2022), and Barson et al. (2024). During the Russia–Ukraine war, the THSI will act as a strong safe-haven for financial stocks, industrial stocks, resources stocks, technology stocks, clean energy, and crude oil while acting as a weak safe-haven for service stocks. Thereby, the THSI can serve as a safe-haven during a crisis, which confirms Figure 2 and Figure 3. Our findings can confirm the result from Ahad et al. (2024), who stated that sustainable stocks can act as a strong safe-haven during geopolitical risks. Likewise, Nittayakamolphun et al. (2024a) also reported that sustainable stocks can act as a strong safe-haven for crude oil during the Russia–Ukraine war (Table 5).

4.3. Granger Causality Test

We added a robustness check using the Granger causality test from the DCC results in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The THSI shows a significant bidirectional causality with clean energy and Thai baht only and a significant unidirectional causality running from consumer products stocks, financial stocks, service stocks, and crude oil to the THSI. Upon examining the causality between the THSI and Thailand’s stock market and financial assets, we recognized insignificant causality, except for clean energy and Thai baht. The findings support the DCC outcome and confirm that our result is trustworthy. Therefore, the THSI can be a diversifier (Table 6).

Table 6.

Granger causality test.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Climate change leads to environmental, social, public health, economic, and finance issues. This has led to investments emphasizing environmental, social, and governance responsibilities or sustainable investment. On the other hand, return and investment risks are still inconsistent, and there is no consensus about the performance of sustainable stocks, particularly in Thailand. Thus, this study analyzes the THSI performance on Thailand’s stock market and financial assets using DCC-GARCH by Engle (2002) with time series data from 2 July 2018 to 30 June 2023. Our findings secure a recommendation to retail and mutual fund investors to diversify risk by making investments in the THSI during a bearish market, given the correlation and high positive volatility between the THSI and Thailand’s stock market, except for consumer products stocks, technology stocks, and all financial assets that bear low positives and exhibit a time-varying relationship. We observed that the movement of Thailand’s stock market will highly affect the THSI, and COVID-19 impacted the economic and investors’ sentiment, resulting in sustainable stock investment to diversify possible risk. Hence, the THSI is highly correlated with Thailand’s stock market and financial assets. On the contrary, the Russia–Ukraine war lightly impacts the THSI; thus, we can consider the THSI a safe-haven for resources stocks, clean energy, gold, and crude oil.

To summarize, the THSI is a weak safe-haven rather than a hedge during extreme movements lower than 1% for consumer products stocks, bitcoin, and Thai baht. In such cases, for every industry in Thailand’s stock market and the rest of the financial assets, the THSI is a diversifier. The Granger causality test validates the diversification function of the THSI. During COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine war, the THSI will act as a weak hedge merely for gold but a strong safe-haven for industrial stocks, while the THSI will act as a strong and a weak safe-haven differently in every industry in Thailand’s stock market and financial assets during both shocks, except Thai baht. Regarding the performance of the THSI, investing in the THSI can be a diversifier during a bearish market. Nevertheless, the overall result lacked a strong hedge or a strong safe-haven, whereas sustainable investment is growing as a trend for investors with long-term interests, and the company that has sustainable operations would reflect them in their financial performance (Chen & Mussalli, 2020; Omura et al., 2021; Bunnun & Chancharat, 2023).

Although the result indicates the correlation and the function of the THSI and Thailand’s stock market and financial assets, we cannot absolutely confirm the expected returns. Therefore, we cautiously recommend to retail and mutual fund investors the selection of the THSI in portfolios. The necessity of the THSI is still recommended in the Thailand’s stock market as alternative assets, as the numbers of listed companies can encourage Thailand’s net zero aim. The concern and support are always needed from policymakers by advocating ESG disclosure requirements, granting tax incentives, and enhancing environmental consciousness among retail and mutual fund managers in accordance with a sustainable finance ecosystem.

This research is limited to the examination of Thailand’s sustainable stocks only. Employing the same methodology when examining sustainable stocks from multiple countries or alternative financial assets can result in different outcomes. However, the DCC-GARCH model has a drawback in terms of asymmetric analysis, which can be rectified using quantile-on-quantile regression, and contributes to delivering insights for bullish, bearish, and normal market conditions. In addition, the Sharpe ratio may assist investors in making more effective judgments, which could be future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N., W.B. and P.P.; methodology, P.N., W.B., R.U. and P.P.; resources, P.N., W.B. and N.P.-a.-r.; software, P.N., W.B. and R.U.; validation, P.N., W.B., R.U. and P.P.; formal analysis, P.N., W.B. and P.P.; investigation, P.N., R.U. and P.P.; data curation, P.N. and W.B.; writing—original draft, P.N., W.B., N.P.-a.-r., R.U. and P.P.; writing—review and editing, P.N., W.B., N.P.-a.-r., R.U. and P.P.; visualization, P.P.; supervision, W.B. and N.P.-a.-r.; funding acquisition, P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Management Sciences, Buriram Rajabhat University (Grant number 17/2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express appreciation for the editor and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Lag length selection.

Table A1.

Lag length selection.

| Lags | Loglikelihood | LR | AIC | SIC | HQC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 54,399.880 | NA | −90.794 | −90.735 * | −90.772 * |

| 1 | 54,645.070 | 484.251 | −90.877 * | −89.985 | −90.541 |

| 2 | 54,818.100 | 337.682 | −90.838 | −89.114 | −90.189 |

| 3 | 54,994.470 | 340.077 | −90.805 | −88.249 | −89.842 |

| 4 | 55,148.490 | 293.389 | −90.735 | −87.346 | −89.459 |

| 5 | 55,316.850 | 316.763 | −90.689 | −86.467 | −89.099 |

| 6 | 55,484.260 | 311.049 | −90.642 | −85.587 | −88.737 |

| 7 | 55,633.830 | 274.435 | −90.564 | −84.677 | −88.346 |

| 8 | 55,775.100 | 255.878 | −90.473 | −83.753 | −87.941 |

Note: * Optimal lag length.

Table A2.

Result of DCC-GARCH(1,1) model.

Table A2.

Result of DCC-GARCH(1,1) model.

| Variables | Mean Equation | Variance Equation | Diagnostic Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2(5) | Q2(10) | |||||

| THSI | −1.26 × 10−5 | 2.88 × 10−6 a | 0.109 a | 0.865 a | 8.499 [0.131] | 11.477 [0.386] |

| AGRO | −3.01 × 10−5 | 2.61 × 10−6 a | 0.092 a | 0.884 a | 4.238 [0.516] | 7.962 [0.633] |

| CONS | −7.93 × 10−4 a | 2.02 × 10−7 c | 0.053 a | 0.950 a | 9.548 [0.089] | 9.860 [0.453] |

| FIN | −1.66 × 10−4 | 1.27 × 10−6 a | 0.085 a | 0.912 a | 4.213 [0.519] | 7.263 [0.700] |

| IND | −5.10 × 10−4 | 2.64 × 10−6 a | 0.070 a | 0.917 a | 5.231 [0.388] | 14.207 [0.164] |

| PRO | −1.65 × 10−4 | 1.61 × 10−6 a | 0.083 a | 0.901 a | 7.464 [0.188] | 9.247 [0.509] |

| RES | −4.16 × 10−5 | 3.23 × 10−6 a | 0.102 a | 0.881 a | 2.840 [0.725] | 16.180 [0.104] |

| SER | 4.32 × 10−5 | 2.57 × 10−6 a | 0.086 a | 0.888 a | 3.176 [0.673] | 4.822 [0.903] |

| TECH | 4.25 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−5 a | 0.173 a | 0.783 a | 4.244 [0.515] | 10.668 [0.384] |

| SPCE | 8.62 × 10−4 b | 2.90 × 10−6 a | 0.116 a | 0.883 a | 1.684 [0.891] | 5.513 [0.854] |

| Gold | 2.01 × 10−4 | 5.31 × 10−6 a | 0.097 a | 0.844 a | 0.653 [0.985] | 10.709 [0.381] |

| Oil | 1.24 × 10−3 b | 4.72 × 10−5 a | 0.254 a | 0.740 a | 1.506 [0.912] | 6.046 [0.811] |

| BTC | 1.61 × 10−3 | 3.13 × 10−4 a | 0.144 a | 0.722 a | 9.100 [0.105] | 10.487 [0.399] |

| THB | −2.41 × 10−6 | 9.87 × 10−8 b | 0.041 a | 0.953 a | 8.858 [0.115] | 11.262 [0.337] |

Notes: Superscripts “a”, “b”, and “c” indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The diagnostic test p-values are given in parentheses.

Notes

| 1 | Based on S&P Goldman Sachs commodity index (GSCI) returns at the end of 2021 compared to the end of 2022. |

| 2 | Based on S&P 500 ESG index returns at the end of 2021 compared to the end of 2022. |

References

- Ahad, M., Imran, Z. A., & Shahzad, K. (2024). Safe haven between European ESG and energy sector under Russian-Ukraine war: Role of sustainable investments for portfolio diversification. Energy Economics, 138, 107853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nassar, N. S., Boubaker, S., Chaibi, A., & Makram, B. (2023). In search of hedges and safe havens during the COVID-19 pandemic: Gold versus Bitcoin, oil, and oil uncertainty. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 90, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, E., Hoque, M., Rahman, M. L., Uddin, G. S., & Jayasekera, R. (2022). ESG investment: What do we learn from its interaction with stock, currency and commodity markets? International Journal of Finance and Economics, 27(3), 3623–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asvathitanont, C., & Tangjitprom, N. (2020). The performance of environmental, social, and governance investment in Thailand. International Journal of Financial Research, 11(6), 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, G. R., & Maharana, A. K. (2023). Can equity market risk be diversified with the help of ESG investment and commodities? Global Business Review. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barson, Z., Ofori, K. S., Junior, P. O., Boakye, K. G., & Ampong, G. O. A. (2024). Time-varying connectedness between ESG stocks and BRVM traditional stocks. Journal of Emerging Market Finance, 23(3), 306–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basher, S. A., & Sadorsky, P. (2022). Forecasting bitcoin price direction with random forests: How important are interest rates, inflation, and market volatility? Machine Learning with Applications, 9, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D. G., & Lucey, B. M. (2010). Is gold a hedge or a safe haven? An analysis of stocks, bonds and gold. Financial Review, 45, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D. G., & McDermott, T. K. (2010). Is gold a safe haven? International evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34, 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg Intelligence. (2022). ESG may surpass $41 trillion assets in 2022, but not without challenges. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/esg-may-surpass-41-trillion-assets-in-2022-but-not-without-challenges-finds-bloomberg-intelligence/ (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Bunnun, W., & Chancharat, N. (2023). The mediating role of dividend policy in the relationship between ownership structure and firm performance of Thai listed companies. International Journal of Trade and Global Markets, 17(3–4), 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagli, E. C. C., Mandaci, P. E., & Taşkın, D. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing and commodities: Dynamic connectedness and risk management strategies. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(5), 1052–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., & Mussalli, G. (2020). An integrated approach to quantitative ESG investing. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 46(3), 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döttling, R., & Kim, S. (2024). Sustainability preferences under stress: Evidence from COVID-19. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 59(2), 435–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F. (2002). Dynamic conditional correlation: A simple class of multivariate GARCH models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 20(3), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriani, F., & Natoli, F. (2021). ESG risks in times of COVID-19. Applied Economics Letters, 28(18), 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnphattananusorn, S. (2019). Analysis of relationship and volatilities between foreign exchange market and stock market of Thailand and selected Asian countries. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 40(1), 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. B., Rashid, M. M., Hossain, M. N., Rahman, M. M., & Amin, M. R. (2023). Using green and ESG assets to achieve post-COVID-19 environmental sustainability. Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy, 3(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Casal, A., López-Penabad, M. C., López-Andión, C., & Maside-Sanfiz, J. M. (2020). Diversification and optimal hedges for socially responsible investment in Brazil. Economic Modelling, 85, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, Z. A., Ahad, M., Shahzad, K., Ahmad, M., & Hameed, I. (2024). Safe haven properties of industrial stocks against ESG in the United States: Portfolio implication for sustainable investments. Energy Economics, 136, 107712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsampoxakis, I., Xanthopoulos, S., Basdekis, C., & Christopoulos, A. G. (2024). Can ESG stocks be a safe haven during global crises? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war with time-frequency wavelet analysis. Economies, 12(4), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Xue, M., Liu, H., & Ye, J. (2023). Precious metal as a safe haven for global ESG stocks: Portfolio implications for socially responsible investing. Resources Policy, 80, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M., Saleem, A., & Sági, J. (2022). Are ESG shares a safe haven during COVID-19? Evidence from the Arab region. Sustainability, 14, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., & Karim, S. (2021). Tail dependence between bitcoin and green financial assets. Economics Letters, 208, 110068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., Karim, S., Uddin, G. S., & Junttila, J. (2022). Small fish in big ponds: Connections of green finance assets to commodity and sectoral stock markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 83, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., Rabbani, M. R., Karim, S., & Billah, S. M. (2023). Religion vs. ethics: Hedge and safe haven properties of Sukuk and green bonds for stock markets pre-and during COVID-19. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 16(2), 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayakamolphun, P., Bejrananda, T., & Pholkerd, P. (2022). Stablecoins as safe haven or hedging asset for cryptocurrencies. Applied Economics Journal, 29(2), 45–70. Available online: https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/AEJ/article/view/260150 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Nittayakamolphun, P., Bejrananda, T., & Pholkerd, P. (2024a). Green bonds and ESG stocks as safe haven or hedging asset for other financial assets. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 45(4), 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayakamolphun, P., Bejrananda, T., & Pholkerd, P. (2024b). Asymmetric effects of uncertainty and commodity markets on sustainable stock in seven emerging markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, A., Roca, E., & Nakai, M. (2021). Does responsible investing pay during economic downturns: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters, 42, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedini, L., & Severini, S. (2022). Exploring the hedge, diversifier and safe haven properties of ESG investments: A cross-quantilogram analysis. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/112339/1/MPRA_paper_112339.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Piserà, S., & Chiappini, H. (2024). Are ESG indexes a safe-haven or hedging asset? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in China. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(1), 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinyapon, Y., Nittayagasetwat, A., & Nittayagasetwat, W. (2022). Performance of ESG stocks: Case of stock exchange of Thailand. NIDA Business Journal, 31, 42–60. Available online: https://so10.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/NIDABJ/article/view/89 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Ratner, M., & Chiu, C. C. (2013). Hedging stock sector risk with credit default swaps. International Review of Financial Analysis, 30, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbaniy, G., Khalid, A. A., Rizwan, M. F., & Ali, S. (2022). Are ESG stocks safe-haven during COVID-19? Studies in Economics and Finance, 39(2), 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I., Bamba, M., Verma, B., & Verma, B. (2024). Dynamic connectedness and investment strategies between commodities and ESG stocks: Evidence from India. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 18(3), 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2020). COVID-19 and safer investment bets. Finance Research Letters, 36, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinlapates, P., & Chancharat, S. (2022). Contrarian profits in Thailand sustainability investment-listed versus in stock exchange of Thailand-listed companies. Risks, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M. (2023). ESG performance and corporate financial risk of the alternative capital market in Thailand. Cogent Business & Management, 10, 2168290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M., Khunkaew, R., & Wichianrak, J. (2023). The impact of environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting and female board members on financial performance: Evidence from Thailand. Journal of Accounting Profession, 19(61), 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Stock Exchange of Thailand. (2023a). SETTHSI index. Available online: https://www.set.or.th/en/market/index/setthsi/overview (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- The Stock Exchange of Thailand. (2023b). List of Thailand sustainability investment in 2022. Available online: https://www.setsustainability.com/libraries/710/item/thailand-sustainability-investment-lists (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Umar, Z., Kenourgio, D., & Papathanasiou, S. (2020). The static and dynamic connectedness of environmental, social, and governance investments: International evidence. Economic Modelling, 93, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, Z., Polat, O., Choi, S. Y., & Teplova, T. (2022). The impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on the connectedness of financial markets. Finance Research Letters, 48, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).