Abstract

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency returns show higher volatility than equity, bond, and other asset classes. Increasingly, researchers rely on machine learning techniques to forecast returns, where different machine learning algorithms reduce the forecasting errors in a high-volatility regime. We show that conventional time series modeling using ARMA and ARMA GARCH run on a rolling basis produces better or comparable forecasting errors than those that machine learning techniques produce. The key to achieving a good forecast is to fit the correct AR and MA orders for each window. When we optimize the correct AR and MA orders for each window using ARMA, we achieve an MAE of 0.024 and an RMSE of 0.037. The RMSE is approximately 11.27% better, and the MAE is 10.7% better compared to those in the literature and is similar to or better than those of the machine learning techniques. The ARMA-GARCH model also has an MAE and an RMSE which are similar to those of ARMA.

1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin have been the focus of researchers and practitioners for quite some time. The return time series of cryptocurrencies shows higher volatility, a higher tail risk, and more skewness compared to the equity returns. We find that implementing the conventional time series forecasting techniques with minimal changes produces forecasts that are equivalent to or better than those of the machine learning techniques researchers employ to forecast bitcoin returns. Time series forecasting based only on previous returns can be improvised to take advantage of these properties. Moreover, with the computing power available, we can use time series out-of-sample forecasting on a rolling window basis and with an expanding window to produce good forecasting performance metrics.

Increasingly, researchers and practitioners are using machine learning techniques to forecast cryptocurrencies. These machine learning techniques, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs), RNNs with a long short-term memory (LSTM) layer, Bayesian neural networks, support vector machines, and decision tree models1 have been employed by researchers to produce a good forecasting performance.

Berger and Koubová (2024) compared the econometric time series forecasting method with the machine learning forecasting methods for out-of-sample daily return forecasts. They found that using the forecast performance metric Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which measures the average magnitude of forecasting errors, the machine learning techniques performed better than the ARMA-GARCH model. However, for the mean absolute error (MAE), the ARMA-GARCH model was better. The RMSE metric penalizes large forecasting errors more than the MAE, which treats all errors in an equal fashion. Berger and Koubová (2024) showed that the econometric techniques produce better forecasts most of the time compared to those of the machine learning techniques, but sometimes they produce large errors, and their RMSE is larger than that of machine learning. We feel that the econometric methodology can be further optimized to produce better forecasts.

Description of these methodologies are in this section

Our research question is whether we can use the econometric forecasting techniques to forecast out-of-sample bitcoin returns such that the forecast on the RMSE metric is better than that produced in the literature. Given the availability of computing power, is there any optimization we can perform to produce better performance metrics than those listed in the literature and machine learning techniques? Our research shows it is feasible to use rolling window forecasts, where each window runs an optimized model. In addition, expanding windows with optimization in each window also lead to a good performance. We compute the performance metric of the econometric technique and compare it with that of Berger and Koubová (2024).

The Bitcoin case is one where the techniques employed here are particularly useful because of the extreme return variability in cryptocurrencies. Using rolling or expanding windows with potentially distinct ARMA/ARMA-GARCH models for each window can accurately forecast returns for highly volatile assets like Bitcoin. The model selected for each window is the one that leads to a minimum AIC. Using these distinct models, we forecast out-of-sample returns for the near future (1 day, 5 days, and 10 days) with a lower RMSE or higher forecast accuracy than that of machine learning.

Returns can be forecasted to a high degree of accuracy daily using econometric techniques that traders can use to make informed trade decisions. Moreover, a lower RMSE of variance forecast can help risk managers make decisions that are better informed about the level of bitcoin volatility when considering changing their level of exposure. We show that all of this can be achieved without the use of machine learning techniques.

2. Literature Search

Cryptocurrency, a digital system, consists of a ledger and tokens. The tokens, called crypto tokens, can be used either as a medium of exchange or may represent the stake in a project or security (Pernice & Scott, 2021). The ledger uses distributed ledger technology (DLT) that facilitates numerous participants in authenticating a transaction. Bitcoin is the cryptocurrency system, and ’bitcoin’ is the crypto token, which has its origin in Nakamoto (Nakamoto & Bitcoin, 2008). The DLT used is called the Blockchain, where each new transaction is verified by all or the majority of participants, and those data are added as a new chain to the Blockchain (Nofer et al., 2017). Bitcoin has seen a dramatic increase in its market capitalization. Its market cap was nearly USD 1 billion in the year 2013. Its market capitalization in January 2025 was over USD 2000 billion (Statista market capitalization of bitcoin (BTC) from April 2013 to January 30, 2025). Bitcoin displays high returns, high volatility, and fat tails. Increasingly, machine learning algorithms are used to forecast returns.

There is no consensus among scholars on the definition of machine learning algorithms, but they can be thought of as a group of non-parametric, linear, or nonlinear models; dynamic models; discriminant analysis models; and data reduction models to classify or reduce data or find a relationship between the input(s) and the output(s) (Krishnaswamy et al., 2000). These models make no assumptions about data distributions, are less restrictive than econometric techniques, and are increasingly used in finance and economics (Kraus et al., 2020). Most machine learning algorithms use neural networks (NNs) with supervised or unsupervised learning. According to Goodfellow et al. (2016), NN architecture consists of layer(s) of neurons, where each layer accepts inputs, processes them using an activation function, and passes the processed output to the next layer. The activation function2 transforms a weighted sum of inputs into an output for the next layer. These layers can be arranged in different architectures to form a computational unit. NNs need a training or learning dataset to adjust weights, so that they can forecast. Training or learning is classified as supervised or unsupervised learning. In supervised learning, a training dataset is provided to the algorithm so that the machine learning algorithms can internally set the weights to minimize the loss function or cost function (Krishnaswamy et al., 2000). In unsupervised learning, data modeling is conducted to understand the underlying structure and distribution, and is based on the unsupervised learning design (Reed & Marks, 1999).

Many scholars have applied machine learning techniques to predict Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency prices or returns. Karasu et al. (2018) used the support vector machine (SVM) to predict bitcoin price and showed that it performed better than linear regression. SVM is a supervised regression technique that can utilize both linear and nonlinear methods. Their study period was between 2012 and 2018. Akyildirim et al. (2021) used SVM, random forest, artificial neural networks, and logistic regression with price and trading indicators for 12 cryptocurrencies at daily and minute-level data frequency. They predicted the sign of the returns and found that SVM gave them the best sign forecast. Their study covered the period from 1 April 2013 to 23 June 2018.

Li et al. (2019) used Twitter feeds to predict the price of small-cap cryptocurrencies ZClassic, ZCash, and Bitcoin Private. They used extreme gradient boosting regression (XGBoost), which is a decision tree model. Their study period was for 3.5 weeks, using hourly pricing data. A decision tree is a supervised machine learning algorithm that, based on training data, creates a decision tree capable of performing either regression or classification. The scholars showed that their model forecasts had a 0.81 correlation with the actual data.

Alessandretti et al. (2018) studied 1681 cryptocurrencies between November 2015 and April 2018. They showed that the machine learning algorithms forecast returns better than the simple moving average approach, and the best forecast is produced by long short-term memory (LSTM), a class of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). RNNs are used for time series forecasting, where at each time, a latent or a hidden state is updated together with the output. Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997) showed that RNNs suffer from vanishing gradient problems or exploding gradient problems, where a long data series causes the gradient to decrease or increase exponentially, and no learning can occur. The authors further suggested the use of gates to control the flow of information and laid the foundation of LSTM. Based on design, the gates are able to choose important information to keep or remove from the data processing.

Another approach commonly used is the Bayesian Neural Network (BNN), in which the neural network weights are not point estimates but probability distributions. Jang and Lee (2017) used BNNs to forecast Bitcoin prices using the underlying Blockchain data and found that BNNs produced good forecasts.

From the study of the literature, it was apparent that scholars are using an empirical approach to select factors that could help predict the price or return of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. The scholars used econometric methods, mainly regression and sometimes ARMA models, to benchmark the results with a machine learning algorithm. Since in our study, we want to forecast bitcoin returns, using a univariate time series forecasting, without relying on external factors, but as a function of previous values, previous forecasting errors, or both, we find the study carried out by Berger and Koubová (2024) to be the best comparative study. We also observed that machine learning algorithms were sometimes used to forecast the price of cryptocurrencies. Generally, econometric models can be applied to stationary time series, where a stationary time series is one whose statistical properties like mean, variance, and covariance do not change over time. The price series is not stationary, but the return series is usually stationary.

Berger and Koubová (2024) used daily log returns as input in a rolling window of fixed size and used machine learning and an ARMA-GARCH model to forecast out-of-sample, one period, five periods, and ten periods ahead. The machine learning algorithms used were Fully Connected NN, Simple RNN, Deep RNN, and RNN with LSTM. Fully Connected NN is a simple NN, Simple RNN has one layer of neurons, and Deep RNN has a maximum of three layers of neurons. The econometric method they used was ARMA-GARCH. They found that RNNs, Deep RNN, and RNN with LSTM had lower RMSE compared to the ARMA-GARCH model.

We will use ARMA and ARMA-GARCH models to forecast in an optimized manner to obtain better RMSE.

3. Data

Bitcoin trades every day of the week, and the daily price data is available from Yahoo Finance. The data is available on Yahoo Finance from 17 September 2014 onwards, and our period of study is from 17 September 2014 to 27 January 2025. There are 3785 daily log returns that we can compute between these dates. We compute daily log returns using Equation (1).

We then perform the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) unit root test to check whether the daily return series is stationary. We performed the test with 15 lags, and the test statistic was −14.6092 with a p-value less than 2.24 × 10−16, confirming that the time series is stationary. We also performed the Jarque–Bera (JB) test to check for normality. The JB test statistic was 20,839.64, and the p-value was less than 2.22 × 10−16, which confirms that the daily log returns are not normally distributed.

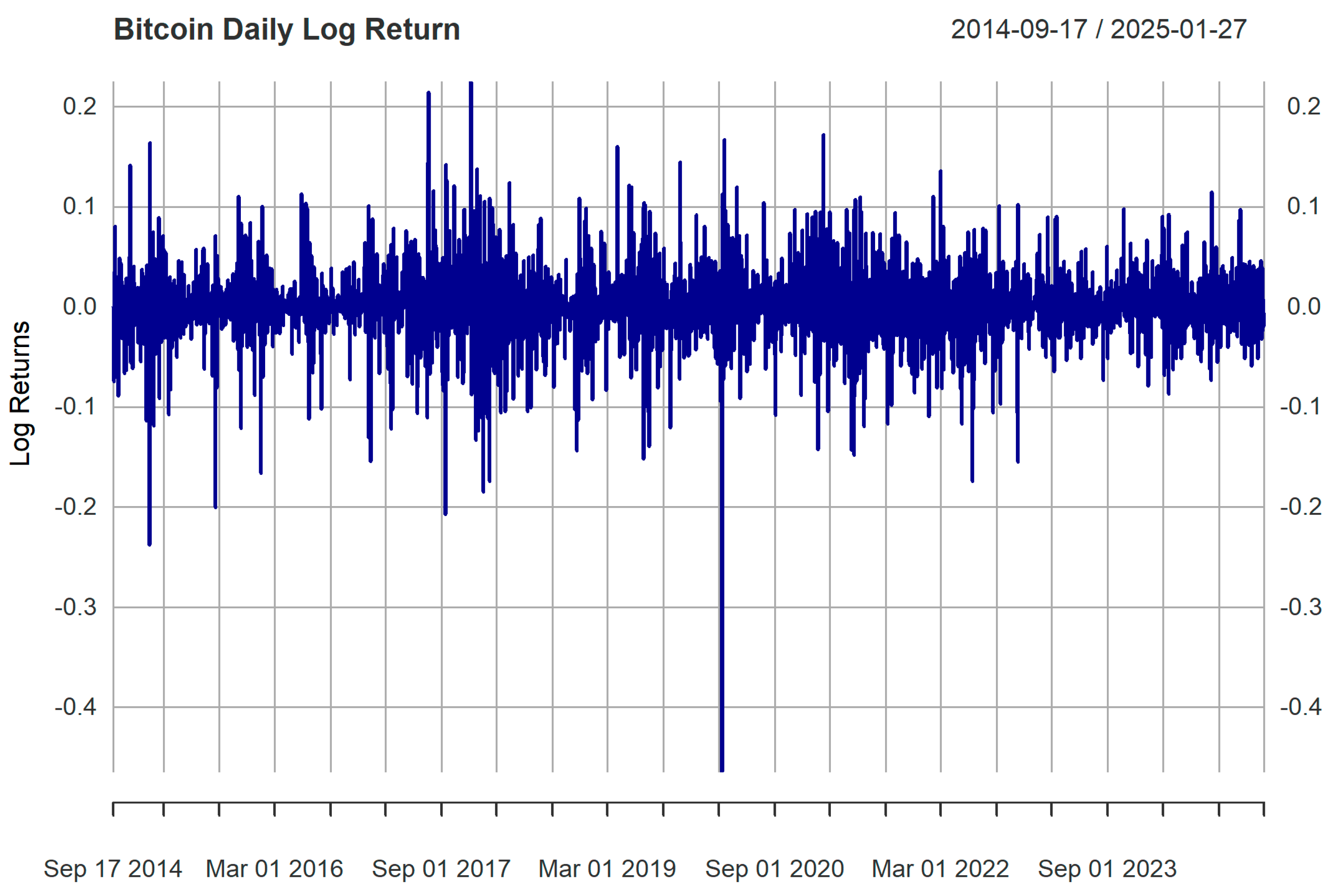

Table 1 presents the summary statistics of daily log returns. We observe that the mean daily return is 0.143% with a standard deviation of 3.638%. It is slightly left-skewed (skewness is less than 0, but not less than −1), suggesting that the mean is less than the median and there is a downside risk. This is due to the fact that Bitcoin has faced sudden price crashes. The kurtosis of Bitcoin’s daily return is 14.40, which suggests it has fat tails (leptokurtic), and from an investment perspective, there are more extreme events and a high tail risk. Figure 1 plots the daily log returns, and one can see that on a daily basis, returns are highly volatile.

Table 1.

Bitcoin daily log return properties from 17 September 2014 to 27 January 2025.

Figure 1.

Bitcoin daily log returns from 17 September 2014 to 27 January 2025.

4. Methodology and Results

In this section, we will discuss the ARMA (x,y) and ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(p,q) methods and the resulting forecasting performance. The main idea is to appropriately select the optimized model to forecast either on a rolling or expanding window basis. Each rolling window could potentially have a different optimized model, but empirically we find that the number of models is far less than the number of rolling or expanding windows.

4.1. ARMA (x,y)

The ARMA model was introduced by Box and Jenkins (1970). This type of time-series modeling utilizes both autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) components. The stationary time series is modeled as a function of its past values in the autoregressive process, and also as a function of errors or residuals in the moving average method. ARMA (x,y) has x AR terms and y MA terms and is expressed as in Equation (2).

In order to determine the appropriate number of AR lags, one generally uses the Partial Autocorrelation Function (PACF). The number of lags after which the PACF cuts off determines x (AR lags). The Autocorrelation Function (ACF) is used to determine the appropriate number of MA lags. Similar to AR lags, the number of lags after which ACF cuts off determines y (MA lags). If we were estimating a complete sample ARMA model, we would be relying on PACF and ACF, but when forecasting, we only have access to past data, and as we move forward in time, we gain more past data. Thus, it makes sense to find the best model conditional on data available at a particular time. In order to do that, we rely on Hyndman and Khandakar (2006, 2008)’s algorithm to select x and y such that the ARMA model has minimum Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Hyndman and Khandakar’s algorithm is optimal for automation when any additional data leads to a new estimation of x and y. AIC is defined as AIC = 2k − 2ln(), where k is the number of parameters of the model and is the maximum value of the likelihood function (Akaike, 1974). AIC is a relative measure of goodness of fit, and a model with a lower AIC is favored. The Hyndman and Khandakar (2006, 2008) algorithm chooses the model that minimizes AIC. AIC leads to better forecasting performance compared to Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for short samples. Only for long samples does BIC show superiority over AIC (Medel & Salgado, 2013).

Forecasting performance is measured by Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE); the lower their values, the better their forecasting performance. The performance metrics are defined in Equations (3) and (4).

Both RMSE and MAE deal with the magnitude of the error as one squares the errors, and the other takes the absolute value of the error. By definition, RMSE is the square root for the mean of squared errors, which results in a higher penalty for large-magnitude errors.

We use two different approaches for forecasting using ARMA(x,y). One involves rolling windows, where the window size is fixed, say at 100, and the initial and final points keep changing by 1 such that the length is 100. This creates “n-100” subsets of the return data, each having a length of 100. We use the Hyndman and Khandakar (2006, 2008) algorithm to select x and y of the ARMA model. Thus, we have “n-100” ARMA models, each having different x and y.

The other method involves expanding size, where the initial point is the beginning of the time series, and the endpoint keeps changing. The endpoint for the first subset is such that the length is equal to the initial window size. If the initial window size is 100, then this also leads to “n-100” subsets of data, and we fit “n-100” ARMA models, each with different x and y as determined by Hyndman and Khandakar (2006, 2008). We have restricted the maximum x and y to 5 due to computing restrictions.

These two approaches are based on the idea that some model fits require a smaller dataset to produce a good forecast, while others require a lot of data. Once we fit the model, we forecast out-of-sample at “t + 1”, “t + 5” and “t + 10” points. Since we have the actual data, we can compute the forecast error. For the whole subset of data, we can compute MAE and RMSE.

ARMA(x,y) Results

Table 2 shows the MAE and RMSE for rolling windows with t + 1, t + 5, and t + 10 forecasts. Papers published in the literature optimize one ARMA(x,y) specification and then compute out-of-sample forecasts. By optimizing x and y for each data window, we are able to achieve a better forecast with lower forecasting error. Berger and Koubová (2024) achieved an RMSE of 0.0402 to 0.0428 for the ARMA-GARCH model with 1, 5, and 10 day out-of-sample forecasts and window sizes of 100, 250, and 500. In contrast, our RMSE using ARMA for rolling window is between 0.03602 and 0.03763 for 1, 5 and 10 days with window sizes of 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 365, 500, and 1000. If we compare the mean RMSE of 0.0415 of Berger and Koubová (2024) with our mean RMSE of 0.036825 we see a decrease in RMSE of 11.27%. This is a good improvement. In terms of MAE, Berger et al.’s estimates were between 0.0261 and 0.0281. We achieved an MAE between 0.0235 and 0.0249. If we consider the mean estimates, then our MAE decreased by 10.70%, which is a good improvement.

Table 2.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample return forecast using ARMA(x,y) on a rolling window.

When we compare the results with the machine learning techniques that Berger and Koubová (2024) used, they achieved a minimum RMSE of 0.0395 for RNN with LSTM for a window size of 500. We still achieved a slightly better performance (0.03602 to 0.03763). Similarly, in terms of MAE, their ARMA-GARCH performance was better compared to other models, but our performance of ARMA was better3.

Table 3 shows the result for an expanding window. Our RMSE estimates are between 0.03593 and 0.03759, similar to the rolling window estimates. On the mean basis, this is an 11.42% better performance than Berger and Koubová. Our MAE varies between 0.0235 and 0.0249 and on a mean basis, it is a 10.70% improvement over Berger and Koubová.

Table 3.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample return forecast using ARMA(x,y) on an expanding window.

We also wanted to dig deeper and find what optimal models were selected by the Hyndman and Khandakar algorithm when we moved from one window to another or one data slice to another. Table 4 shows the details of the ARMA models selected. We restricted the maximum AR and MA lags to 5 due to computing restrictions.

Table 4.

Details about the ARMA (x,y) models selected.

From Table 4, we can see that for rolling windows, the mean model (ARMA(0,0)) is the optimal model for 65.5% of rolling windows when the window size is 100. When the window size increases to 1000, we still find that the mean model is the optimal model for 56.3%. This suggests that the rolling mean model, which is equivalent to the moving average, is sufficient to forecast approximately 60% of the time. We also observe that for rolling windows, either ARMA(2,2) or ARMA(1,1) is selected for a number of data windows. In the rolling window, as we move from one window to another, the model changes only 10.67% to 29.34% with a mean of 14.26%4.

For expanding windows, we observe that for smaller window sizes, the mean model or the ARMA(0,0) model is still a good choice, and approximately 50% of the time, a mean model will work. Since this is an expanding window, a mean model interpretation is not of a moving average but a mean with a growing sample size. For larger window sizes like 500 and 1000, the mean model is totally useless in forecasting. The second most used model is ARMA(2,2) for smaller windows, and for larger windows like 500 and 1000, the ARMA(2,0) model is used.

We also computed RMSE and MAE using the Hyndman and Khandakar algorithm where BIC is minimized, and our results are consistent with AIC results5. BIC penalizes complex models, and our results are consistent for AIC and BIC minimization using the Hyndman and Khandakar algorithm. This consistency provides further support for an optimization-based approach.

We also optimized our computation time for the ARMA(x,y) model. We employed parallel computing and used the “stepwise” search procedure as suggested by Hyndman and Khandakar. In the stepwise search procedure, all models are not evaluated. A decent initial model is taken, and AR and/or MA orders are changed to see how the information criteria change. The objective is to reduce information criteria. We used a 10-year-old DELL XPS 8920 with 7th generation intel i7 running windows 10 on 64 GB RAM. To produce one MAE and RMSE for rolling window, our computation time varied from 28.23 s to 66.17 s. For the expanding window, it varied between 136.34 sec and 177.79 s.

4.2. ARMA (x,y)-GARCH(p,q)

ARMA (x,y) assumes constant variance or homoscedastic errors, whereas the real-world financial time series shows that volatility changes with time or contains heteroscedastic errors. Standard GARCH (Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity) was introduced by (Bollerslev, 1986) and can be modeled with mean and variance equations. In ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(p,q), the mean equation is ARMA(x,y). The conditional variance of the residuals or error term is modeled as a function of past variance and past square residuals. In the GARCH(p,q) process, there are “p” past variance terms and “q” ARCH terms of squared residuals. Equations (5a), (5b), and (5c) describe the ARMA(x,y) and standard GARCH(p,q) process.

We limit ourselves to the GARCH(1, 1) process, which is commonly used in financial time series to model volatility clustering. It is parsimonious and models volatility clustering where conditional high volatility is followed by periods of higher conditional volatility. The standard GARCH model is symmetric, where positive or negative shock similarly affects the conditional variance. GARCH(1,1) conditional variance is given by Equation (5c), with p = 1, q = 1.

The ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) model estimates both the mean and the variance simultaneously, producing forecasts that are different from those of the standalone ARMA(x,y) model. ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) will also consider volatility clustering and heteroscedasticity.

The academic literature has confirmed that Bitcoin volatility is asymmetric (Baur & Dimpfl, 2018). It has been found that asymmetric GARCH models produce better models for bitcoin return volatility and that positive shocks increase conditional variance more than negative shocks. Recent studies, such as Wu and Xu (2024), have confirmed this asymmetry.

Two of the most common asymmetric models used are EGARCH (Nelson, 1991) and GJRGARCH (Glosten et al., 1993). In EGARCH(1,1), the conditional variance is given by Equation (6), where the natural log of present conditional variance is expressed as the natural log of past conditional variance.

For GJRGARCH(1,1), conditional variance is given by Equation (7), where I is an indicator function that takes values of 1 and 0 for negative and positive shocks, respectively.

In Equation (6), the parameter captures the impact of asymmetry on the EGARCH model. If is negative, then negative shocks will lead to a relatively greater increase in conditional variance than a positive shock. Similarly, for GJRGARCH, determines asymmetry by capturing the leverage effect. If is positive, then a negative shock relatively increases volatility more than a positive shock.

4.2.1. Results for ARMA (x,y)-GARCH(p,q)

Table 5, Panel A, summarizes the AIC criteria for different models for the full sample. We find that EGARCH with Student’s T innovation has the lowest AIC of −4.234. This suggests that there is some evidence of asymmetry and fat tails. The point to note is that AIC is very similar among different GARCH models, and these full-sample GARCH models are practically similar (Burnham & Anderson, 2002).

Table 5.

Details of the full sample estimation of ARMA(x,y) Garch(1,1) models.

To further investigate asymmetry, we looked at the parameter for GJRGARCH and EGARCH under normal and Student’s T innovation. Panel B summarizes the results, where for GJRGARCH, we find that is not significant under robust error. For EGARCH, we find that is significant and positive, meaning that positive shocks increase conditional variance more relative to negative shocks. We also find that when we use the Student’s T distribution, the shape parameter, representing the degrees of freedom of the Student’s T distribution, is small. This tells us that Bitcoin returns have high kurtosis and heavy tails.

4.2.2. Results for Return Forecast Using ARMA (x,y)-GARCH(p,q)

As in ARMA(x,y), we use the same two approaches: the rolling and expanding windows. We find the best ARMA(x,y) to model the mean equation using the Hyndman and Khandakar (2006, 2008) algorithm. Then, we model the GARCH process as GARCH(1,1).

We find that the mean forecasting performances as measured by RMSE and MAE are similar for Standard GARCH, EGARCH, and GJRGARCH; as such, we present only standard GARCH results6.

Table 6 details the forecasting performance of the ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) model for returns on a rolling basis. We observe that on a rolling basis, our MAE is between 0.0235 and 0.02478 compared to Berger and Koubová’s (2024) MAE, between 0.0261 and 0.0281. On a mean basis, it is an improvement of 10.92%, similar to what we achieved with the ARMA(x,y) model. In terms of RMSE, our RMSE is between 0.03605 and 0.03749, while Berger and Koubová’s (2024) RMSE is between 0.0402 and 0.0428. On a mean basis, that is an improvement of 11.40%, similar to what we achieved for the ARMA(x,y) model.

Table 6.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample return forecast using ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) on a rolling window.

Table 7 is similar to Table 6, where return forecasts are on an expanding window basis. We observe that MAE ranges from 0.02348 to 0.02479, comparable to what we found on a rolling basis. Similarly, RMSE is between 0.03593 and 0.03748, comparable to what we achieved on a rolling basis.

Table 7.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample return forecast using ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) on an expanding window.

Our observation is that ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) offers the same or a slight improvement in forecasting performance for returns measured by MAE and RMSE compared to an optimized ARMA(x,y) model. This is expected as the GARCH model primarily estimates or forecasts conditional variance.

4.2.3. Results for Conditional Variance Forecast Using ARMA (x,y)-GARCH(p,q)

GARCH models conditional variance, and we can compute the MAE and RMSE of conditional variance forecasts using either a rolling or an expanding window. The forecasts are compared to a simple proxy of realized variance, namely, the square of daily log returns. In using the square of daily log returns as a proxy for realized returns, we are relying on the works of Pagan and Schwert (1990) and Andersen et al. (2003). Table 8 and Table 9 detail the MAE and RMSE for conditional variance.

Table 8.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample conditional variance forecast using ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) on a rolling window.

Table 9.

MAE and RMSE for out-of-sample conditional variance forecast using ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) on an expanding window.

We observed in Table 5 that for EGARCH was positive and significant, which signifies that asymmetry and positive shocks lead to a relatively greater increase in volatility compared to negative shocks. In return forecasts, the forecast performance was quite similar for standard GARCH, EGARCH, and GJRGARCH. In conditional volatility forecasting, we observe that standard GARCH and GJRGATCH are similar to EGARCH results, but EGARCH produces stable MAE and RMSE; there are fewer outliers. As such, we present the ARMA(x,y)-EGARCH(1,1) results7. On a rolling basis, the MAE of conditional volatility is between 0.00209 and 0.00347, and the RMSE is between 0.0052 and 0.00977. On an expanding window basis, the MAE is between 0.00201 and 0.00229, and the RMSE is between 0.005 and 0.00562. Empirically, we observe that the expanding window creates the best and most stable RMSE for conditional variance. In contrast, for the return forecast, both the rolling and expanding windows have the same forecasting performance. This could be because good conditional variance forecasts require more data than return forecasts.

GARCH primarily models conditional variance. Shen et al. (2021) showed that in terms of RMSE, GARCH models performed better compared to RNN, whereas in terms of MAE, the RNN model performed better than GARCH. Dudek et al. (2024) showed that different models perform better depending on the forecast horizon and forecast performance metric. Dudek et al. (2024) achieved a Mean Square Error (MSE), defined as a square of RMSE, of 0.215 × 10−4 for the GARCH model. Since the MSE is the square of RMSE, the RMSE value for Dudek et al. (2024) is 0.004636. Our RMSE on a rolling window based on daily data ranges from 0.0052 to 0.0097 and on an expanding window basis is 0.005 to 0.00562, which is not better than Dudek’s results. Similarly, Dudek et al. (2024) achieved an MAE of 0.138 × 10−2. We obtained an MAE of 0.00209 to 0.00347, which is 0.209 × 10−2 to 0.347 × 10−2 on a rolling basis. On an expanding basis, our MAE ranges from 0.00201 to 0.00209, which is 0.201 × 10−2 to 0.209 × 10−2. One of the probable reasons for better results for Dudek is that their study period was limited from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2021, whereas our study period is from 17 September 2014 to 27 January 2025. During this period, bitcoin prices have been highly volatile. FTX, one of the biggest crypto exchanges, went bankrupt in 2022, and after President Trump became president for the second time, Bitcoin prices increased rapidly.

Dudek machine learning models achieved better RMSE and MAE. Nevertheless, in our present econometric forecasting, we optimize only the ARMA process and keep the GARCH process constant as GARCH(1,1). A direction for future research is to develop an algorithm to optimize ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(x,y) simultaneously. We feel that such a methodology could produce forecasting performance similar to or better than the machine learning techniques. We tried the brute force technique, but it is computationally very intensive and is not recommended.

Since the mean and variance equations of GARCH specifications are connected, this research shows that optimizing the ARMA(x,y) part can produce forecasts better than machine learning techniques. Then, using the technique described in the paper, we may produce similar or better volatility forecasts.

5. Conclusions

We find that running the ARMA model either on a rolling basis or on an expanding window basis can produce good return forecasts with minimum MAE and RMSE for daily Bitcoin returns. Our methodology of choosing the best model for each window or data slice produces forecasting performance better or at the same level as machine learning techniques. The best model is defined as the one with minimum AIC.

When we dig deeper to find the AR and MA orders of the models selected for return forecasting, we find that the ARMA(0,0) or mean model is selected for rolling windows and for expanding windows with small window sizes for the majority of the windows. Thus, instead of a full-sample optimized model, if we were to optimize each rolling or expanding window, we would increase the forecast performance, and instead of over-fitting, we are choosing a mean model and other optimized ARMA models. The research shows some relevance of naive forecasting techniques like moving averages.

When we applied ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1), where the ARMA order is optimized but not the GARCH process, we still observed that the return forecast performance is the same as that of ARMA models. The conditional variance forecast performance is also better, especially for expanding windows.

The machine learning techniques still produced better conditional variance forecasts, but we feel that our methodology could be improved for the ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(1,1) process. Instead of just optimizing the ARMA order or the return equation of the GARCH specification (Equation (5a)), we should optimize the ARMA(x,y)-GARCH(p,q) model for each data slice. Optimization will involve choosing appropriate x, y, p, and q that would lead to the lowest AIC.

Forecasting Bitcoin returns is challenging due to high volatility. In this work, we showed that parsimonious econometric techniques are still relevant in forecasting Bitcoin returns and variance. Moreover, these techniques are not black boxes like machine learning and provide details that provide valuable insight into the modeling process and produce forecasts with similar or better accuracy compared to machine learning techniques. This accurate forecast provides valuable information for traders and risk managers.

Author Contributions

P.A. contributed towards conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—original draft, and reviewing and editing. A.M.S. contributed towards conceptualization, methodology, and writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Yahoo Finance at https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/BTC-USD/history/?period1=1410912000&period2=1748978462.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ronald Balvers for his comments and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARMA | Autoregressive Moving Average |

| GARCH | Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| NN | Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| BNN | Bayesian Neural Network |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| EGARCH | Exponential Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| GJRGARCH | Glosten–Jagannathan–Runkle GARCH |

Notes

| 1 | Brief descriptions of these methodologies are in the literature search section. |

| 2 | , where is a transformation function—sigmoid or rectifier. |

| 3 | Berger and Koubová’s (2024) study period is from 28 April 2013 to 12 December 2021. We have data from Yahoo Finance, which starts from 17 September 2014 to 27 January 2025. Though our data is not similar, we have data from when Bitcoin prices were highly volatile due to the FTX collapse and President Trump’s reelection. |

| 4 | In computing this, we have used the ratio of # of model transitions to # of windows. |

| 5 | If requested, we can provide the MAE and RMSE with BIC minimization. |

| 6 | If requested, we can provide return forecast performance for EGARCH and GJRGARCH with Student’s t innovations. |

| 7 | Results for standard GARCH and GJRGARCH are available on request. |

References

- Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildirim, E., Goncu, A., & Sensoy, A. (2021). Prediction of cryptocurrency returns using machine learning. Annals of Operations Research, 297, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandretti, L., ElBahrawy, A., Aiello, L. M., & Baronchelli, A. (2018). Anticipating cryptocurrency prices using machine learning. Complexity, 2018(1), 8983590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. G., Bollerslev, T., Diebold, F. X., & Labys, P. (2003). Modeling and forecasting realized volatility. Econometrica, 71(2), 579–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D. G., & Dimpfl, T. (2018). Asymmetric volatility in cryptocurrencies. Economics Letters, 173, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T., & Koubová, J. (2024). Forecasting bitcoin returns: Econometric time series analysis vs. machine learning. Journal of Forecasting, 43(7), 2904–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, T. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31(3), 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P., & Jenkins, G. M. (1970). Time series analysis: Forecasting and control. Holden-Day. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, G., Fiszeder, P., Kobus, P., & Orzeszko, W. (2024). Forecasting cryptocurrencies volatility using statistical and machine learning methods: A comparative study. Applied Soft Computing, 151, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L. R., Jagannathan, R., & Runkle, D. E. (1993). On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess return on stocks. The Journal of Finance, 48(5), 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., Courville, A., & Bengio, Y. (2016). Deep learning (Vol. 1, No. 2). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural Computation, 9(8), 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R. J., & Khandakar, Y. (2006, June 15–17). Automatic time series forecasting. Book of Abstracts: For 2nd International R User Conference (p. 76), Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/conferences/useR-2006/Abstracts/Abstracts.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hyndman, R. J., & Khandakar, Y. (2008). Automatic time series forecasting: The forecast package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H., & Lee, J. (2017). An empirical study on modeling and prediction of bitcoin prices with bayesian neural networks based on blockchain information. IEEE Access, 6, 5427–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, S., Altan, A., Saraç, Z., & Hacioğlu, R. (2018, May 2–5). Prediction of bitcoin prices with machine learning methods using time series data. 2018 26th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Izmir, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M., Feuerriegel, S., & Oztekin, A. (2020). Deep learning in business analytics and operations research: Models, applications and managerial implications. European Journal of Operational Research, 281(3), 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, C. R., Gilbert, E. W., & Pashley, M. M. (2000). Neural network applications in finance: A practical introduction. Financial Practice and Education, 10(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. R., Chamrajnagar, A. S., Fong, X. R., Rizik, N. R., & Fu, F. (2019). Sentiment-based prediction of alternative cryptocurrency price fluctuations using gradient boosting tree model. Frontiers in Physics, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, C. A., & Salgado, S. C. (2013). Does the BIC estimate and forecast better than the AIC? Economic Analysis Review, 28(1), 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S., & Bitcoin, A. (2008). A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Bitcoin, 4(2), 15. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Nelson, D. B. (1991). Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 59, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofer, M., Gomber, P., Hinz, O., & Schiereck, D. (2017). Blockchain. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 59, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pagan, A. R., & Schwert, G. W. (1990). Alternative models for conditional stock volatility. Journal of Econometrics, 45(1–2), 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, I. G. A., & Scott, B. (2021). Cryptocurrency. Internet Policy Review, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R., & Marks, R. J., II. (1999). Neural smithing: Supervised learning in feedforward artificial neural networks. Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z., Wan, Q., & Leatham, D. J. (2021). Bitcoin return volatility forecasting: A comparative study between GARCH and RNN. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista market capitalization of bitcoin (BTC) from April 2013 to January 30, 2025. (2025). Available online: https://www-statista-com.scsu.idm.oclc.org/statistics/377382/bitcoin-market-capitalization (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Wu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2024). The asymmetric return-realized higher moments relations in the bitcoin market. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5076564 (accessed on 1 February 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).