Corporate Governance and Employee Productivity: Evidence from Jordan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses

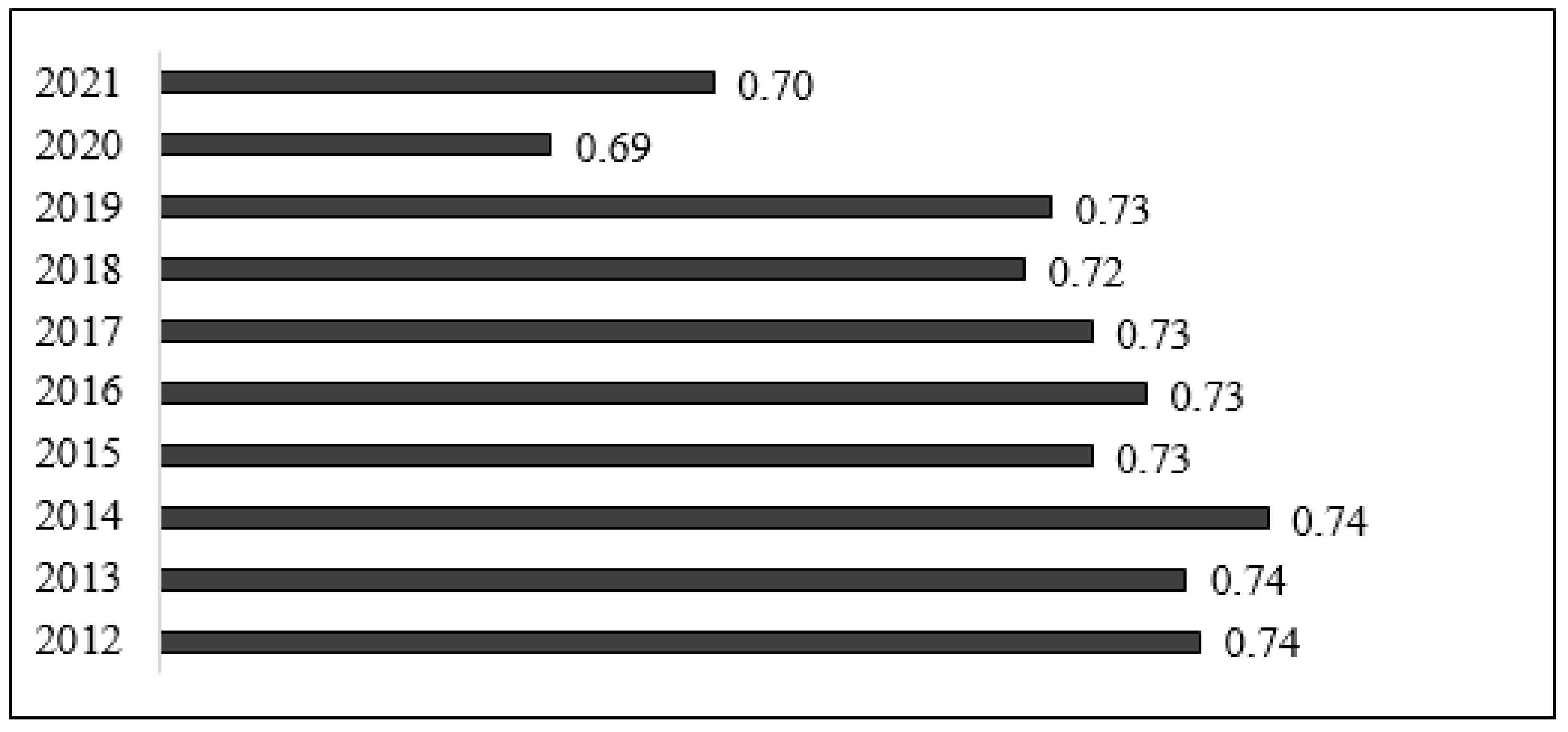

3.1. Employee Productivity

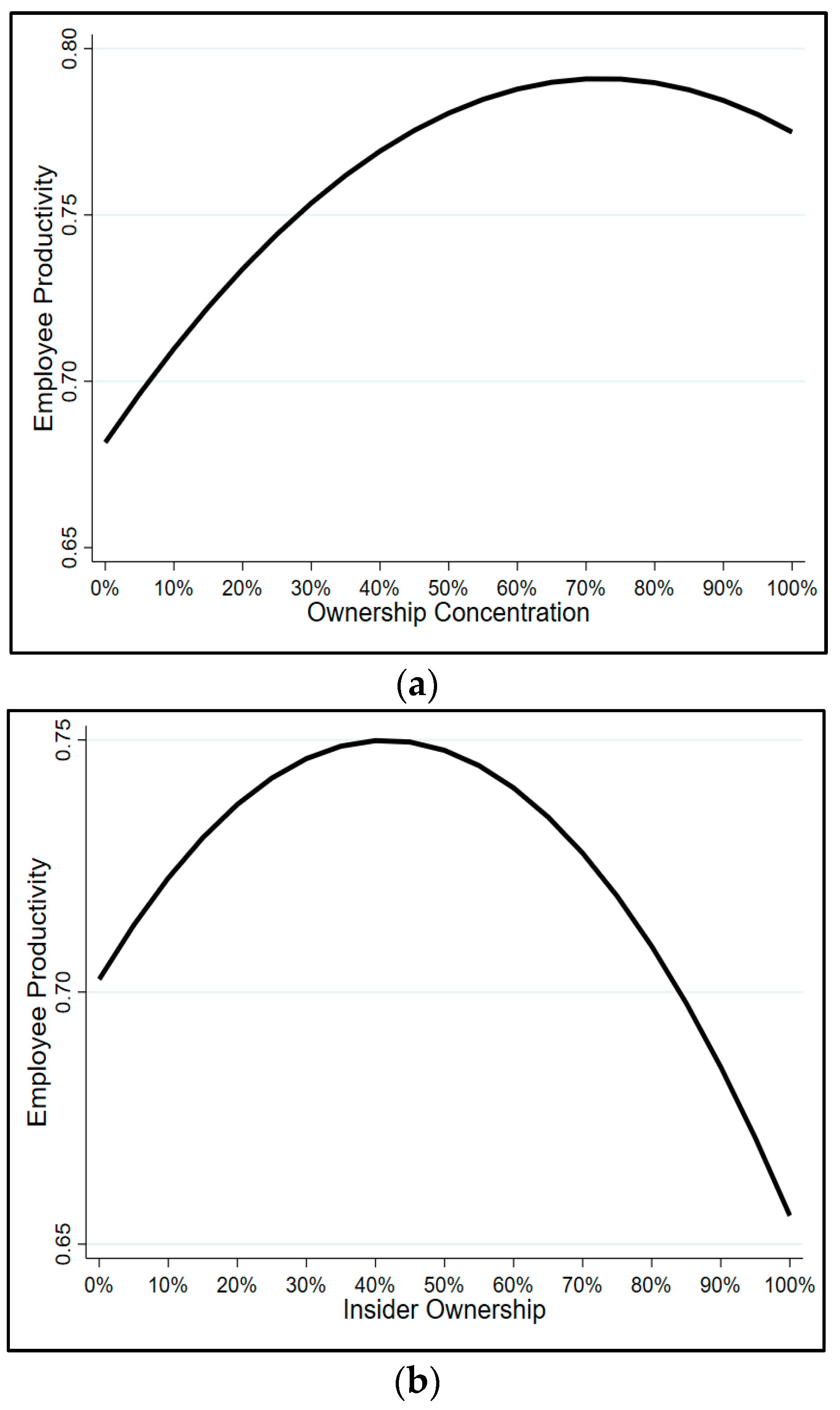

3.2. Ownership Concentration

3.3. Insider Ownership

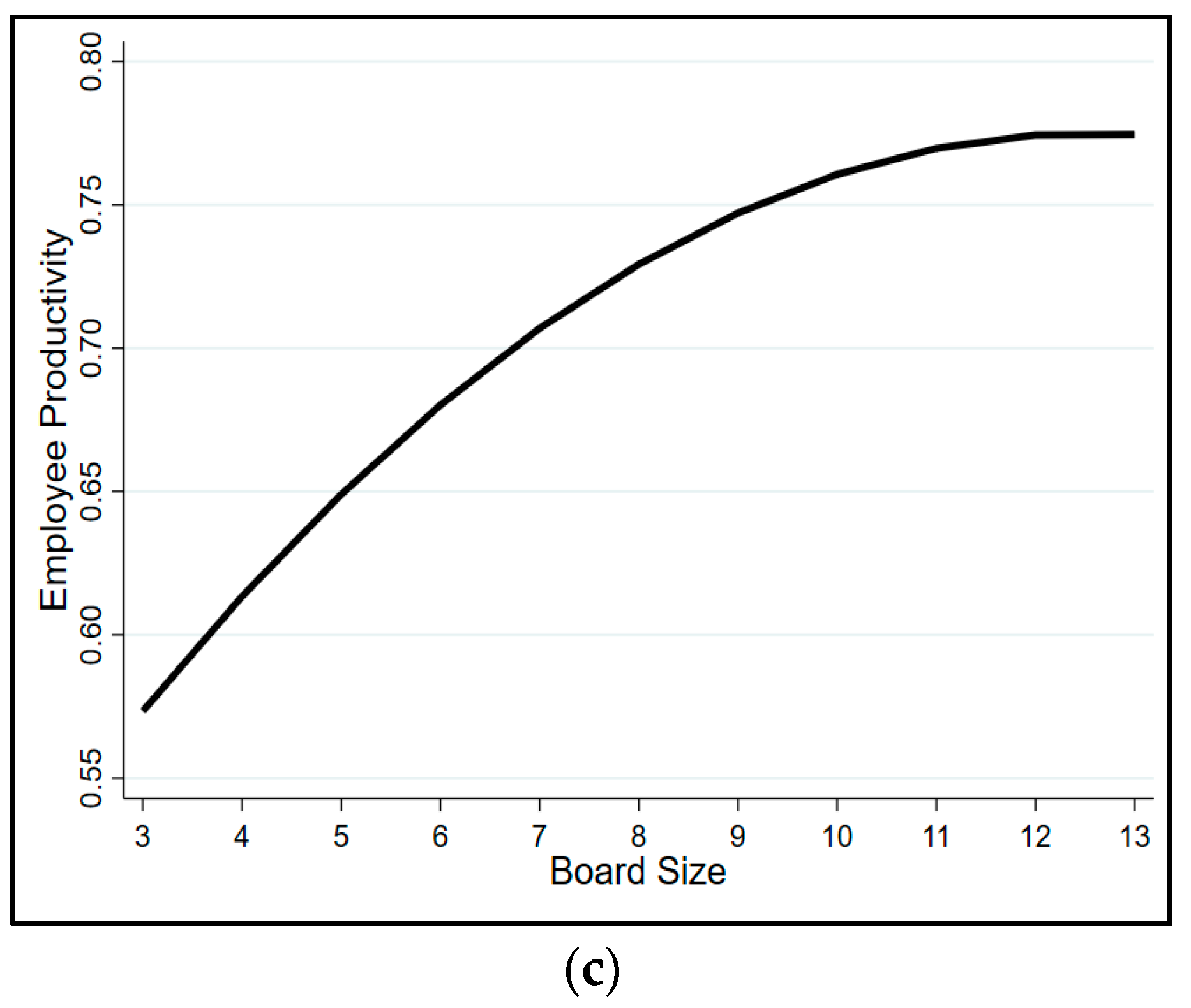

3.4. Board Size

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Definitions and Measures of the Variables

4.3. Research Model

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Correlations

5.2. Regression Results

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Mike, and Philip Hardwick. 1998. An Analysis of Corporate Donations: United Kingdom Evidence. Journal of Management Studies 35: 641–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, Isaac, Emmanuel S. Tenakwah, Emmanuel J. Tenakwah, and Mary Amponsah. 2022. Corporate Governance and Performance of Pension Funds in Ghana: A Mixed-Method Study. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljifri, Khaled, and Mohamed Moustafa. 2007. The Impact of Corporate Governance Mechanisms on the Performance of UAE Firms: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 23: 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, Ebraheem S. S. 2016. Ownership structure and earnings management: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 24: 135–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amman Stock Exchange. 2012. Privatization in Jordan. Available online: https://www.ase.com.jo/en/Media-Center/Library-Publications/Privatization-Jordan (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Berg, Alexander, and Tatiana Nenova. 2004. Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC) Corporate Governance Country Assessment. World Bank 35088. Available online: http://econ.worldbank.org (accessed on 3 February 2005).

- Bermig, Andreas, and Bernd Frick. 2010. Board Size, Board Composition, and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Germany. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabra, Gurmeet S. 2007. Insider ownership and firm value in New Zealand. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 17: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, Wilko, Leo de Haan, Marco Hoeberichts, Maarten R. Van Oordt, and Job Swank. 2012. Bank Profitability during Recessions. Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 2552–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, Mike, Denis Gromb, and Fausto Panunzi. 2014. Large Shareholders, Monitoring, And the Value of the Firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 693–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Shijun, John H. Evans, and Nandu J. Nagarajan. 2008. Board size and firm performance: The moderating effects of the market for corporate control. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 31: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Min Hsien, and Jia Hui Lin. 2007. The Relationship between Corporate Governance and Firm Productivity: Evidence from Taiwan’s manufacturing firms. Journal compilation 15: 768–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Manseek, and Soonwook Hong. 2022. Another Form of Greenwashing: The Effects of Chaebol Firms’ Corporate Governance Performance on the Donations. Sustainability 14: 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, Stijn, and Simeon Djankov. 1999. Ownership Concentration and Corporate Performance in the Czech Republic. Journal of Comparative Economics 27: 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, Lina M., Iván, A. Durán, Sandra Gaitán, and Mateo Vasco. 2017. Mergers and Acquisitions in Latin America: Industrial Productivity and Corporate Governance. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53: 2179–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demsetz, Harold. 1983. The structure of ownership and the theory of the firm. Journal of Law and Economics 26: 375–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, Harold, and Belen Villalonga. 2001. Ownership structure and corporate performance. Journal of Corporate Finance 7: 209–33. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929-1199(01)00020-7 (accessed on 1 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, Harold, and Kenneth Lehn. 1985. The Structure of Corporate Ownership: Causes and Consequences. Journal of Political Economy 93: 1155–77. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1833178 (accessed on 1 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Dorothy, Oyo Ita, Worlu Rowland, and Udoh Iboro. 2020. Effect of Participatory Management on Employees’ Productivity among Some Selected Banks, Lagos, Nigeria. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 19: 1544–458. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/effect-of-participatory-management-on-employees-productivity-among-some-selected-banks-lagos-nigeria-9804.html (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Drobetz, Wolfgang, Malte Janzen, and Igmacio Requejo. 2019. Capital allocation and ownership concentration in the shipping industry. Transportation Research Part E 122: 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Khoa D., Tran N. Huynh, Diep V. Nguyen, and Hoa T. Phan Le. 2022. How Innovation and Ownership Concentration Affect the Financial Sustainability of Energy Enterprises: Evidence from a Transition Economy. Heliyon 8: 10474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, Jude, and Francisco J. Acedo. 2021. External supports, innovation efforts and productivity: Estimation of aCDM model for small firms in developing countries. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 173: 121–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Agency Problems and Residual Claims. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 327–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanoski, Filip, Moorad Choudhry, Milivoje Davidovic, and Bruno Sergi. 2018. What Does Affect Profitability of Banks in Croatia? Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 28: 338–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Paul M. 2009. The impact of board size on firm performance: Evidence from the UK. The European Journal of Finance 15: 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Ki C., and David Y. Suk. 1998. The effect of ownership structure on firm performance: Additional evidence. Review of Financial Economics 7: 143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Chi Kun. 2005. Corporate Governance and Corporate Competitiveness: An international analysis. Corporate Governance 13: 211–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, Chun Keung, Jun Xiong, and Hong Zou. 2020. Ownership identity and corporate donations: Evidence from a natural experiment in China. China Finance Review International 10: 113–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horobet, Aalexandra, Lucian Belascu, Stefania Cristina Curea, and Alma Pentescu. 2019. Ownership Concentration and Performance Recovery Patterns in the European Union. Sustainability 11: 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrovatin, Nevenka, and Sonja Uršič. 2002. The determinants of firm performance after ownership transformation in Slovenia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 35: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Quibin. 2020. Ownership concentration and bank profitability in China. Economics Letters 196: 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Ichiro, and Satoshi Mizobata. 2019. Ownership Concentration and Firm Performance in European Emerging Economies: A Meta-Analysis. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 56: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, Aziz, and Mahmoud El-Shawa. 2009. Ownership concentration, board characteristics and performance: Evidence from Jordan. Accounting in Emerging Economies 9: 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Bhawana, Sangeetha Gunasekar, and Purushartha Balasubramanian. 2020. Capital contribution, insider ownership and firm performance: Evidence from Indian IPO firms. International Journal of Corporate Governance 11: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janang, Jennifer T., Rosita Suhaimi, and Norhana Salamudin. 2015. Can Ownership Concentration and Structure be linked to Productive Efficiency? Evidence from Government Linked Companies in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance 31: 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael, and William Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Derek C., and Mark Klinedinst. 2012. Insider Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence from Bulgaria. Advances in the Economic Analysis of Participatory & Labor-Managed Firms 13: 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsie, Anjala, and Shikha M. Shrivastav. 2016. Analysis of Board Size and Firm Performance: Evidence from NSE Companies Using Panel Data Approach. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance 9: 148–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Shaojie, Hongyan Liang, Zilong Liu, Xiaoling Pu, and Jianing Zhang. 2022. Ownership concentration among entrepreneurial firms: The growth-control trade-off. International Review of Economics and Finance 78: 122–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaughy, Daniel L., Michael C. Walker, Glenn V. Henderson, Jr., and Chandra S. Mishra. 1998. Founding Family Controlled Firms: Efficiency and Value. Review of Financial Economics 7: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, Xuan T. T., Ha T. N. Nguyen, Thanh Ngo, Tu D. Q. Li, and Lien P. Nguyen. 2023. Efficiency of the Islamic Banking Sector: Evidence from Two-Stage DEA Double Frontiers Analysis. International Journal of Financial Studies 11: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Thanh, and Tu Le. 2019. Capital market development and bank efficiency: A cross-country analysis. International Journal of Managerial Finance 15: 478–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Pascal, Nahid Rahman, Alex Tong, and Ruoyun Zhao. 2015. Board size and firm value: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Management and Governance 20: 851–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, Vincent, and Nicole Cramer. 2010. The relationship between firm performance and board characteristics in Ireland. European Management Journal 28: 387–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, Asare Y., and Emmanuel Boachie. 2018. The impact of IT-technological innovation on the productivity of a bank’s employee. Cogent Business & Management 5: 1470449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omane-Adjepong, Maurice, Asampana A. Killian, and Osei-Assibey Kwame. 2024. Chaos in Financial Markets: Research Insights, Measures, and Influences. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, Mohammed, Ali Bolbol, and Ayten Fatheldin. 2008. Corporate governance and firm performance in Arab equity markets: Does ownership concentration matter? International Review of Law and Economics 28: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2015. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/g20-oecd-principles-of-corporate-governance-2015_9789264236882-en (accessed on 30 November 2015). [CrossRef]

- Panda, Brahmadev, and N. M. Leepsa. 2017. Agency theory: Review of Theory and Evidence on Problems and Perspectives. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance 10: 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, Manoj, and Manoranjan Pattanayak. 2007. Insider Ownership and Firm Value: Evidence from Indian Corporate Sector. Economic and Political Weekly 42: 1459–1467. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4419499 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Park, Kwangmin, and Shawn Jang. 2010. Insider ownership and firm performance: An examination of restaurant firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management 29: 448–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, Rehana. 2021. Corporate Governance in Saudi Arabia: Analysis of Current Practices. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=CORPORATE+GOVERNANCE+IN+SAUDI+ARABIA%3A+ANALYSIS+OF+CURRENT+PRACTICES&btnG= (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Qadorah, Almontaser A. M., and Faudziah H. B. Fadzil. 2018. The Relationship between Board Size and CEO Duality and Firm Performance: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Risk Management 3: 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Pedro M. N., and Antonio. P. S. Pinto. 2021. Corporate ownership concentration drivers in a context dominated by private SME’s. Heliyon 7: 8–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Caspar. 2005. Managerial Ownership and Firm Performance in Listed Danish Firms: In Search of the Missing Link. European Management Journal 23: 542–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Partha P., Sandeep Rao, and Min Zhu. 2022. Mandatory CSR expenditure and stock market liquidity. Journal of Corporate Finance 72: 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdiyanto, Rusdiyanto. 2021. Discipline and Work Environment Affect Employee Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Entrepreneurship 25: 1099–9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluy, Ahmad B., Zainal Abidin, Masyhudzlhak Djamil, Novawiguna Kemalasari, Lamminar Hutabarat, Sri M. Pramudena, and Endri Endri. 2021. Employee productivity evaluation with human capital management strategy: The case of COVID-19 in Indonesia. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 27: 1–9. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/employee-productivity-evaluation-with-human-capital-management-strategy-the-case-of-covid19-in-indonesia-12408.html (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- San Martin-Reyna, Juan M., and Jorge A. Duran-Encalada. 2015. Effects of Family Ownership, Debt and Board Composition on Mexican Firms Performance. International Journal of Financial Studies 3: 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Securities Depository Center. 2017. Instructions of Corporate Governance for Shareholding Listed Companies for the Year 2017. Available online: https://sdc.com.jo/sites/default/files/2023-07/corporate_governance_instructions.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- Shahrier, Nur Ain, Jessica S. Yin Ho, and Sanjaya S. Gaur. 2018. Ownership concentration, board characteristics and firm performance among Shariah-compliant companies. Journal of Management and Governance 24: 365–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, Her Jiun, and Chi Yih Yang. 2005. Insider Ownership and Firm Performance in Taiwan’s Electronics Industry: A Technical Efficiency Perspective. Managerial and Decision Economics 26: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Malin, Xiongfeng Pan, and Xionyou Pan. 2020. Chapter Three—Analysis of influencing factors and efficiency of marine resource utilization in China. Sustainable Marine Resource Utilization in China 26: 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, Bruce, and Nada Elnahla. 2020. The roles played by boards of directors: An integration of the agency and stakeholder theories. Transnational Corporations Review 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, Sheela, Ahnaf A. Alsmady, Ibrahim Izani, and Tanaraj Krishna. 2024. Corporate Governance Dynamics in Saudi Arabia: Audit Committee Composition, Family Ownership, and Financial Performance. Migration Letters 21: 1587–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Gloria Y., and Garry Twite. 2011. Corporate governance, external market discipline and firm productivity. Journal of Corporate Finance 17: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, Ana B., and Younghwan Lee. 2022. Real Earnings Management, Firm Value, and Corporate Governance: Evidence from the Korean Market. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, Ana Belén, HoKyun Shin, Younghwan Lee, and Chang Won Lee. 2020. Relationship among CSR Initiatives and Financial and None—Financial Corporate Performance in the Ecuadorian Banking Environment. Sustainability 12: 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, Shann. 2000. Corporate Governance: Theories, Challenges and Paradigms. Gouvernement d’entreprise:Théories, Enjeux et paradigmes 1: 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, Filippo, Nicola Raimo, and Michele Rubino. 2019. Board characteristics and integrated reporting quality: An agency theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, Abdul, and Qaisar A. Malik. 2019. Board characteristics, ownership concentration and firms’ performance a contingent theoretical based approach. South Asian Journal of Business Studies 8: 146–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Emma. 2003. The Relationship between Ownership Structure and Performance in Listed Australian Companies. Australian Journal of Management 28: 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2024. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/2?country=IRN&l=en (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Yong-bae, Ji, and Lee Choonjoo. 2009. Data Envelopment Analysis in Stata. The Stata Journal 9: 1–13. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Data+Envelopment+Analysis+in+Stata&btnG= (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Zeitun, Rami, and Gary G. Tian. 2007. Does ownership affect a firm’s performance and default risk in Jordan? The International Journal of Business in Society 7: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., and Jianping Li. 2020. Chapter 10—Big-data-driven low-carbon management. Big Data Mining for Climate Change 7: 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CG Mechanism | Agency Theory | Stewardship Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership Concentration | Solution to reduce the agency problems | Focus more in improving the insider ownership |

| Insider Shareholding | Obstruct the monitoring role of board of directors | Increase managerial power is better for monitoring firm’s performance |

| Board Size | Bigger size is better for monitoring firm’s performance | Smaller size is better for making efficient decisions |

| Author | Sample | Country | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Horobet et al. 2019) | 3506 European firms from 2008 to 2016 | Europe | Positive |

| (Duong et al. 2022) | 103 energy firms from 2007 to 2020 | Vietnam | Positive |

| (Omran et al. 2008) | 304 firms from 2000 to 2002 | Arab countries | Positive |

| (San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada 2015) | 75 listed firms from 2005 to 2011 | Mexico | Positive |

| (Jaafar and El-Shawa 2009) | 103 listed firms over from to 2005 | Jordan | Positive |

| (Zeitun and Tian 2007) | 59 listed firms from 1989 to 2002 | Jordan | Positive |

| (Drobetz et al. 2019) | 126 listed shipping firms from 1997 to 2016 | Worldwide | Positive |

| (Huang 2020) | All listed banks over from to 2018 | China | Positive |

| (Iwasaki and Mizobata 2019) | Meta-synthesis of 1517 estimates 69 studies | Worldwide | Positive |

| (Claessens and Djankov 1999) | 706 firms from 1992 to 1997 | Czech | Positive |

| (Lai et al. 2022) | 1658 entrepreneurial firms from 2004 to 2011 | Worldwide | No impact |

| (Demsetz and Lehn 1985) | 511 firms from 1976 to 1980 | USA | No impact |

| (Janang et al. 2015) | 31 listed firms from 2001 to 2012 | Malaysia | No impact |

| Author | Sample | Country | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Sheu and Yang 2005) | 416 listed electronics firms from 1996 to 2001 | Taiwan | Negative |

| (Han and Suk 1998) | 5500 firms from 1988 to 1992 | Worldwide | Negative |

| (Jones and Klinedinst 2012) | 490 manufacturing firms from 1997 to 2001 | Bulgaria | No impact |

| (Pant and Pattanayak 2007) | 1833 firms for the years 2000, 2001, 2003 and 2004 | India | Non-linear * |

| (Bhabra 2007) | 54 firms from 1994 to 1998 | New Zealand | Non-linear ** |

| (Jain et al. 2020) | 199 firms from 2007 to 2018 | India | Non-linear * |

| (Park and Jang 2010) | 251 restaurant firms from 2001 to 2006 | Worldwide | Positive |

| (Rose 2005) | All listed firms from 1998 to 2001 | Denmark | Positive |

| (Hrovatin and Uršič 2002) | 488 firms in 1998 | Slovenia | Positive |

| Author | Sample | Country | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Bermig and Frick 2010) | 294 firms from 1998 to 2007 | Germany | No impact |

| (Guest 2009) | 746 listed firms from 1981 to 2002 | United Kingdom | Negative |

| (Cheng et al. 2008) | 500 firms from 1984 to 1991 | USA | Negative |

| (Nguyen et al. 2015) | 1141 firms from 2001 to 2011 | Australia | Negative |

| (O’Connell and Cramer 2010) | 77 listed firms in 2001 | Ireland | Negative |

| (Shahrier et al. 2018) | 200 Shariah-compliant listed firms from 2014 to 2017 | Malaysia | Negative |

| (Jaafar and El-Shawa 2009) | 103 listed firms from 2002 to 2005 | Jordan | Positive |

| (Kalsie and Shrivastav 2016) | 145 non-financial firms from 2008 to 2012 | India | Positive |

| Variable Name | Description | Obs e | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Variable Label | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: | ||||||

| Employee Number | Number of employees | 1360 | 462 | 836 | 2 | 7191 |

| EMPNO b | ||||||

| Total Sales | Non-financial firms: total revenues; Financial firms: total Interest income; Insurance firms: total premiums income | 1360 | 109 × 106 | 413 × 106 | 29,930 | 6510 × 106 |

| SALES ($) b | ||||||

| Employee Productivity | Measured by DEA tool, EMPNO is input and SALES is output | 1360 | 0.73 | 0.285 | 0.008 | 1 |

| EP a | ||||||

| Independent Variables: | ||||||

| Ownership Concentration | HHI of Top 5 Major Shareholders who held 5% or more | 1360 | 20.6 | 22.33 | 0.25 | 99.99 |

| OC (%) a b | ||||||

| Insider Shareholding | Proportion of shares held insiders who held 5% or more of shares | 1360 | 24.3 | 25.00 | 0 | 99 |

| INSH (%) c | ||||||

| Board Size | Number of board of directors members | 1360 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 13 |

| BMS b | ||||||

| Control Variables: | ||||||

| Firm Size | Natural Logarithm of Total Assets | 1360 | 18.1 | 1.774 | 14.79 | 24.88 |

| SIZE a b | ||||||

| Leverage Ratio | Total Debt/Total Assets | 1360 | 41.7 | 28.09 | 0 | 100 |

| LVRG (%) a b | ||||||

| Firm Age | Number of Years: Financial Year—Year of Incorporation | 1360 | 29 | 17.52 | 3 | 92 |

| AGE a b | ||||||

| Capital Expenditure | Net property, plant and equipment/Total Assets | 1360 | 25.7 | 27.05 | 0 | 98.9 |

| CAPEX (%) a b | ||||||

| Market to Book Value | Market Value of Equity/Book Value of Equity | 1360 | 1.13 | 2.969 | 0.13 | 104.8 |

| MVBV a b | ||||||

| GDP Growth per Labor GDPL (%) a d | Annual Growth rate of (Jordanian GDP/Total Labor force) | 1360 | −0.32 | 5.290 | −8.05 | 7.69 |

| Financial Firm | Dummy: 1 if the firm is related to financial sector, 0 otherwise | 1360 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| FIN b | ||||||

| Variable | VIF | EP | OC | INSH | BMS | SIZE | LVRG | AGE | CAPEX | MVBV | GDPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | 1.16 | 0.12 | 1 | ||||||||

| INSH | 1.08 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 1 | |||||||

| BMS | 1.74 | 0.43 | −0.24 | −0.22 | 1 | ||||||

| SIZE | 2.20 | 0.58 | 0.07 | −0.23 | 0.56 | 1 | |||||

| LVRG | 1.73 | 0.51 | 0.10 | −0.16 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 1 | ||||

| AGE | 1.38 | 0.35 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 1 | |||

| CAPEX | 1.08 | 0.13 | 0.005 | 0.04 | −0.14 | −0.20 | −0.25 | −0.09 | 1 | ||

| MVBV | 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.004 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1 | |

| GDPL | 1.00 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1 |

| FIN | 1.84 | 0.27 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.01 | −0.66 | −0.09 | −0.001 |

| Mean VIF | 1.50 | ||||||||||

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient |

| t-value | t-value | t-value | t-value | t-value | t-value | t-value | |

| OC | 0.001 | ** 0.003 | ** 0.003 | ||||

| 1.65 | 2.2 | 2.41 | |||||

| OCQ | ** −0.0001 | ** −0.0001 | |||||

| −2 | −2.02 | ||||||

| INSH | 0.0001 | *** 0.002 | *** 0.002 | ||||

| 0.23 | 3.1 | 3.16 | |||||

| INSHQ | *** −0.0001 | *** −0.0001 | |||||

| −3.4 | −3.59 | ||||||

| BMS | 0.003 | * 0.032 | * 0.032 | ||||

| 0.84 | 1.92 | 1.96 | |||||

| BMSQ | * −0.002 | * −0.002 | |||||

| −1.89 | −1.91 | ||||||

| SIZE | *** 0.179 | *** 0.179 | *** 0.180 | *** 0.181 | *** 0.178 | *** 0.177 | *** 0.177 |

| 11.4 | 11.52 | 11.43 | 11.85 | 11.18 | 11.15 | 11.71 | |

| LVRG | *** −0.103 | *** −0.098 | *** −0.106 | *** −0.126 | *** −0.105 | *** −0.100 | *** −0.113 |

| −2.82 | −2.67 | −2.88 | −3.37 | −2.85 | −2.7 | −2.98 | |

| AGE | *** −0.007 | *** −0.006 | *** −0.007 | *** −0.007 | *** −0.008 | *** −0.007 | *** −0.005 |

| −7.34 | −6.02 | −8.42 | −8.64 | −8.03 | −7.58 | −4.97 | |

| CAPEX | −0.026 | −0.03 | −0.029 | −0.029 | −0.029 | −0.031 | −0.031 |

| −0.33 | −0.38 | −0.36 | −0.36 | −0.36 | −0.39 | −0.39 | |

| MVBV | *** −0.002 | *** −0.002 | *** −0.002 | *** −0.002 | *** −0.002 | *** −0.002 | *** −0.001 |

| −4.1 | −4.21 | −4.3 | −4.33 | −4.28 | −4.23 | −4 | |

| GDPL | 0.004 | 0.011 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.003 | 0.013 |

| 0.39 | 0.94 | −0.31 | −0.36 | −0.53 | −0.3 | 1.08 | |

| FIN | *** −0.367 | *** −0.4 | *** −0.366 | *** −0.385 | *** −0.36 | *** −0.371 | *** −0.425 |

| −10.25 | −10.01 | −8.66 | −9.45 | −10.32 | −10.46 | −9.38 | |

| Obs | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 |

| R-squared | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Firm FE | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year FE | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Het. test | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Likelihood-ratio test | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | |||

| EP | Coefficient |

| t-value | |

| EP t-1 | *** 1.011 |

| 4.94 | |

| OC | ** 0.004 |

| 2.43 | |

| OCQ | ** −0.0001 |

| −2.46 | |

| INSH | * 0.001 |

| 1.92 | |

| INSHQ | * −0.00002 |

| −1.89 | |

| BMS | 0.014 |

| 1.05 | |

| BMSQ | −0.001 |

| −0.87 | |

| SIZE | 0.001 |

| 0.32 | |

| LVRG | 0.028 |

| 1.27 | |

| AGE | −0.0001 |

| −0.11 | |

| CAPEX | −0.008 |

| −0.41 | |

| MVBV | *** −0.002 |

| −3.72 | |

| GDPL | 0.00004 |

| 0.07 | |

| FIN | −0.013 |

| −1.09 | |

| Obs | 1088 |

| Year FE | Included |

| Arellano-Bond test for AR(1) | 0.01 |

| Arellano-Bond test for AR(2) | 0.11 |

| Sargan test of overid | 0.12 |

| Hansen test of overid | 0.21 |

| GMM Hansen test | 0.30 |

| GMM Difference (null H = exogenous) | 0.18 |

| OC | INSH | BMS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | Coefficient | EP | Coefficient | EP | Coefficient |

| t-value | t-value | t-value | |||

| OC = 0% | *** 0.003 | INSH = 0% | *** 0.002 | BMS = 3 | *** 0.042 |

| 3.01 | 3.57 | 3.65 | |||

| OC = 10% | *** 0.003 | INSH = 10% | *** 0.002 | BMS = 4 | *** 0.038 |

| 3.15 | 3.44 | 3.9 | |||

| OC = 20% | *** 0.002 | INSH = 20% | *** 0.001 | BMS = 5 | *** 0.033 |

| 3.34 | 3.12 | 4.25 | |||

| OC = 30% | *** 0.002 | INSH = 30% | ** 0.001 | BMS = 6 | *** 0.029 |

| 3.55 | 2.25 | 4.71 | |||

| OC = 40% | *** 0.001 | INSH = 40% | 0.0001 | BMS = 7 | *** 0.025 |

| 3.63 | 0.33 | 5.27 | |||

| OC = 50% | *** 0.001 | INSH = 50% | −0.0005 | BMS = 8 | *** 0.020 |

| 2.93 | −1.59 | 5.49 | |||

| OC = 60% | 0.001 | INSH = 60% | ** −0.001 | BMS = 9 | *** 0.016 |

| 1.39 | −2.55 | 4.34 | |||

| OC = 70% | 0.0001 | INSH = 70% | *** −0.002 | BMS = 10 | ** 0.011 |

| 0.19 | −2.98 | 2.48 | |||

| OC = 80% | −0.0003 | INSH = 80% | *** −0.002 | BMS = 11 | 0.007 |

| −0.5 | −3.19 | 1.14 | |||

| OC = 90% | −0.001 | INSH = 90% | *** −0.003 | BMS = 12 | 0.002 |

| −0.9 | −3.31 | 0.31 | |||

| OC = 100% | −0.001 | INSH = 100% | *** −0.003 | BMS = 13 | −0.002 |

| −1.16 | −3.39 | −0.21 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ajlouni, A.; Bastida, F.; Nurunnabi, M. Corporate Governance and Employee Productivity: Evidence from Jordan. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2024, 12, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040097

Ajlouni A, Bastida F, Nurunnabi M. Corporate Governance and Employee Productivity: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2024; 12(4):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040097

Chicago/Turabian StyleAjlouni, Abdullah, Francisco Bastida, and Mohammad Nurunnabi. 2024. "Corporate Governance and Employee Productivity: Evidence from Jordan" International Journal of Financial Studies 12, no. 4: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040097

APA StyleAjlouni, A., Bastida, F., & Nurunnabi, M. (2024). Corporate Governance and Employee Productivity: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12040097