1. Introduction

Schumpeter (

1911) classically suggested that financial development (encompassing both institutions and markets) is instrumental in shaping economic growth, which has consistently been supported by much subsequent research, including

Levine’s (

2003) observation of “more finance, more growth”. The financial sector needs to be developed to bring about economic development, which occurs through the creation and expansion of financial institutions and financial markets, which facilitate substantial investments and growth. Such developments contribute to poverty reduction and an overall increase in welfare (

Beck and Levine 2004;

Bertocco 2008;

Kemal et al. 2008;

Levine 1997,

2003;

McKinnon 1993;

Rahaman 2011). Financial development enhances knowledge about profitable opportunities and promotes the efficient allocation of resources, driven by the creation of financial institutions, which reduce costs of obtaining information and increase contract and transaction implementation efficiency (

King and Levine 1993a,

1993b;

Demetriades and Hussein 1996;

Levine et al. 2000;

Hassan et al. 2011). Moreover, increased financial access fosters dynamic efficiency, stimulating structural modifications through innovation and overall economic advantages (see

Rajan and Zingales 1998;

Al-Yousif 2002;

Jalil et al. 2010).

A contrary perspective, pioneered by

Robinson (

1952), posits that finance makes an insignificant contribution to economic growth and is conversely driven by the latter.

Wijnberg (

1983) and

Buffie (

1984) argued that, following financial development, borrowers from the informal sector shift to the formal sector, decreasing overall credit availability and restricting national economic growth.

Lucas (

1988) further contended that there is a limited impact of financial markets on an economy’s growth. It has been shown in various studies that the influence of financial development on economic growth depends on several interconnected variables, including inflation, financial sector policies, government size, trade openness, and per capita income, legal frameworks, cultural factors, and state ownership of banks (

Rousseau and Wachtel 2002;

Stulz and Williamson 2003;

Yilmazkuday 2011;

Abiad and Mody 2005;

Ang 2008;

Yilmazkuday 2011;

Andrianova et al. 2008); other factors like remittances, trade and financial flexibility, political structures, and the quality of institutions can also have an effect (

Rajan and Zingales 2003;

Girma and Shortland 2008;

Huang et al. 2010;

Law 2009;

Roe and Siegel 2011;

Aggarwal et al. 2011;

Law and Azman-Saini 2012;

Law et al. 2018). These mediating factors indicate that the state of the economy affects financial development. Furthermore,

Ibrahim (

2007) and

Loayza and Ranciere (

2006) asserted that any impact of financial development on economic growth is ephemeral.

While some have suggested a nonlinear relationship between financial development and economic growth,

Ang (

2008) stressed that studies need to develop an accurate definition of functional forms to understand this relationship. Economic conditions can change abruptly, making nonlinear relationships more realistic regarding impacts on financial development. Assuming a linear relationship between finance and growth when there might be triggers for regime shifts could lead to inaccuracies in linear models’ predictions. By incorporating nonlinear features, such as threshold points, policymakers can better manage the amount of money to be expanded, as these points indicate critical levels for financial development’s impact on growth. To ensure the reliability and accuracy of estimates concerning the nonlinearity of the finance–growth relationship, appropriate measurements are essential for policymakers to utilize as a guide. A thorough understanding of this relationship allows policymakers to address specific issues and make informed decisions regarding the regulation, oversight, and monitoring of financial intermediaries.

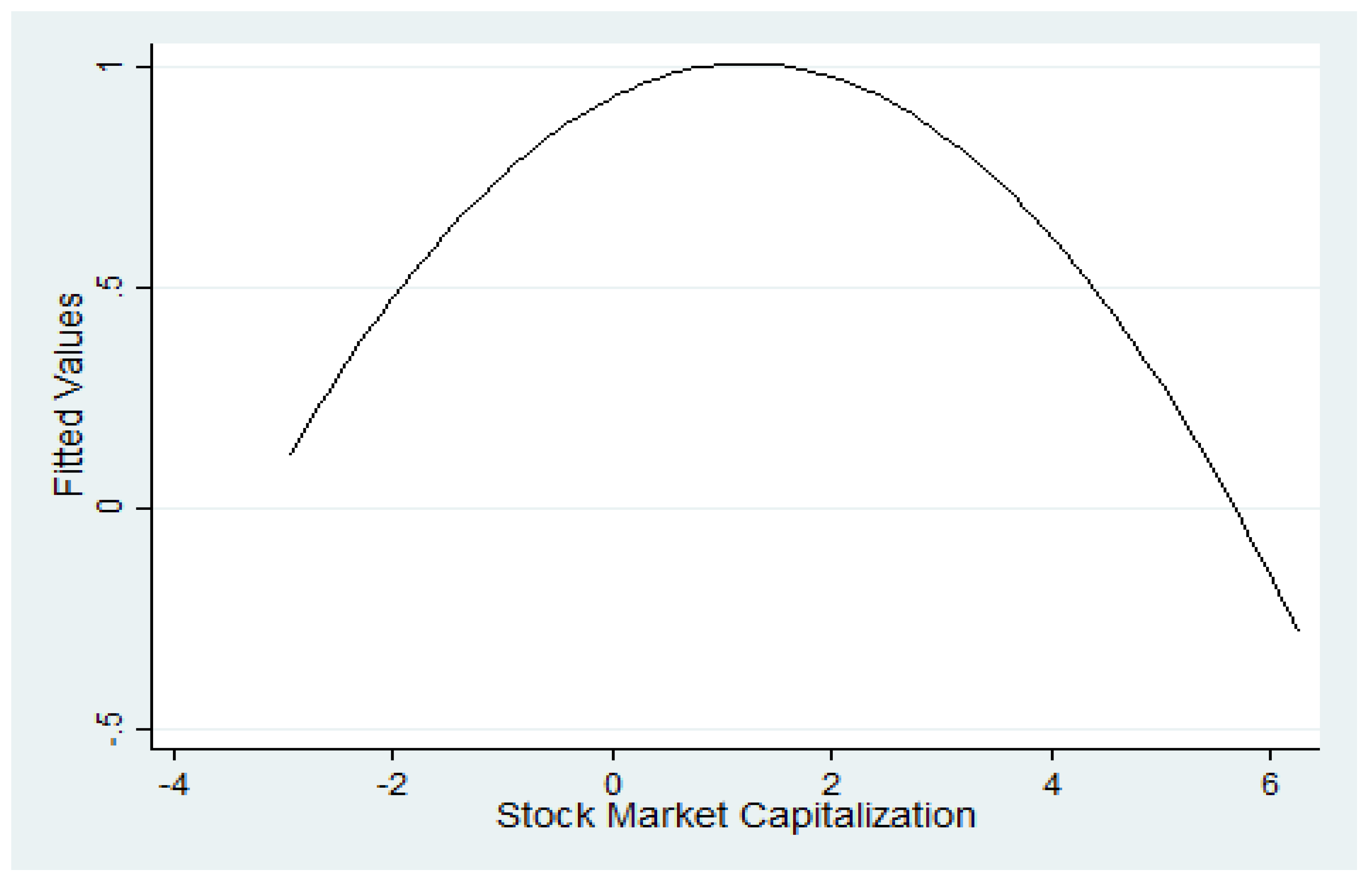

According to some studies, economic growth slowed down when financial development increased, with a nonlinear correlation represented by an inverted U-shape or Kuznets curve (

Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012). Inefficiencies in the derivative market were identified as the driving force behind this phenomenon, hindering the normative direction of financial flow (

Law and Singh 2014;

Arcand et al. 2015). Consequently, excessive liquidity without appropriate regulation and supervision could lead to what is known as the “financial curse”, i.e., the idea that “too much finance harms growth” (

Samargandi et al. 2015).

Aghion et al. (

2005) also argued that the nonlinearity in the link between financial development and growth might be a limiting factor for the impact on economic growth. However, in a meta-analysis exploring the effect of financial development on economic growth carried out by

Asongu (

2013), contrasting results to the pioneering study of

Schumpeter (

1911) were determined.

Several reasons have been identified in recent studies for the nonlinear correlation between finance and growth that is represented by the inverted U-shaped curve. One factor is the presence of corruption within the banking sector, such as the unstable adherence to laws or political interference, which can lead to the misallocation of funds towards ineffective or even wasteful endeavors, thus limiting the positive impact of increased financial development on economic growth (

Law et al. 2018). Furthermore, the ease of obtaining investment loans through commercial credit can facilitate productive investment. However, household loans are commonly utilized for non-productive objectives, such as personal consumption, with limited national economic growth benefits (

Hung 2009). Another issue is that the financial sector employs only 3.9% of all workers; consequently, continued expansion of the industry leads to limited macroeconomic growth in terms of human capital (

Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012). Finally, it was observed by

De Gregorio and Guidotti (

1995) that if the financial sector undergoes liberalization under an unfavorable regulatory framework, greater financial intermediation may adversely affect growth.

The existing literature continues to present conflicting hypotheses regarding the relationship between finance and economic growth, arguing “more finance, more growth” (

Levine 2003) and the opposite (

Arcand et al. 2015;

Law and Singh 2014).

Law and Singh (

2014) specifically questioned whether the negative impact of excessive financial activity on growth is only temporary. In this study, we aimed to contribute to the ongoing discussion by investigating the legitimacy of the “too much finance harms growth” theory, using the latest panel data for MENA countries for the years 1996–2022. MENA countries are of particular interest for this research, as financial development is considered a critical factor propelling regional economic growth. We sought to determine if there is nonlinearity in the finance–growth relationship and if the inverted U-shaped curve found in previous studies persisted during the years 1996–2022, indicating that financial activities are not effectively regulated and monitored. Additionally, we hypothesized that if the relationship between finance and growth modified to a U-shaped curve in the same period, then the negative impact of “too much finance” on growth would be temporary in MENA countries, indicative of robust financial systems in more recent economies with concurrent economic growth.

The rationale for this study’s economic focus has two key aspects. Firstly, despite the extensive body of research on financial development and economic growth, there is a notable gap when it comes to conducting in-depth analyses specific to the MENA region. The MENA nations face distinctive socio-economic challenges, encompassing issues like political instability, regional conflicts, reliance on finite resources (particularly oil and gas), elevated youth unemployment, the imperative need to diversify their economies, education and skill disparities, water scarcity, income inequality, and limited access to healthcare. These specific challenges call for a dedicated examination of how financial institutions and markets influence economic growth within this unique context. Secondly, the existing literature offers contradictory findings regarding the nonlinear relationship between financial development and economic growth. It indicates the presence of threshold effects and the potential for adverse consequences resulting from excessive financial development. Policymakers must grasp these complex dynamics, as inadequately regulated financial expansion could lead to economic imbalances and impede the pursuit of sustainable development. The main objective of this study was to evaluate whether the nonlinear relationship between financial development and economic growth is consistent, specifically the inverted U-shaped curve identified in earlier studies (

Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012;

Law and Singh 2014;

Arcand et al. 2015). Data from the period 1996–2022 were used for this purpose, which have not been included in previous research. As a result, different outcomes than those observed in earlier studies could be obtained, potentially supporting the hypothesis of a temporary effect of “too much finance harms economic growth” in MENA countries from 1996 to 2022.

The primary focus of this study was to assess the extent to which the roles of financial institutions and financial markets contribute to economic growth in MENA countries during the period 1996–2022, while also addressing endogeneity. Empirical studies carried out on the relationship between finance, institutions, markets, and growth in the past have generally backed a positive and monotonic relationship. Thus, this study aimed to investigate whether there might be a nonlinear correlation with a potential maximum threshold effect. This study aimed to explore the complementarity between financial institutions and financial markets, as measured by the financial development index of MENA economies. It sought to determine whether a well-developed financial sector, comprising both institutions and markets, creates a conducive environment for favorable growth effects on the overall financial industry. Additionally, this study investigated if the effect of either financial institutions or financial markets on economic growth becomes apparent only after a certain minimum threshold level is surpassed by the financial development index. This led to two essential questions:

Is the relationship between either financial institutions or financial markets and economic growth consistent with the overall level of financial development?

To what extent can either financial institutions or financial markets make more significant contributions to the process of economic growth? (i.e., are there any variations in the effects of financial institutions in comparison to financial markets on economic growth?)

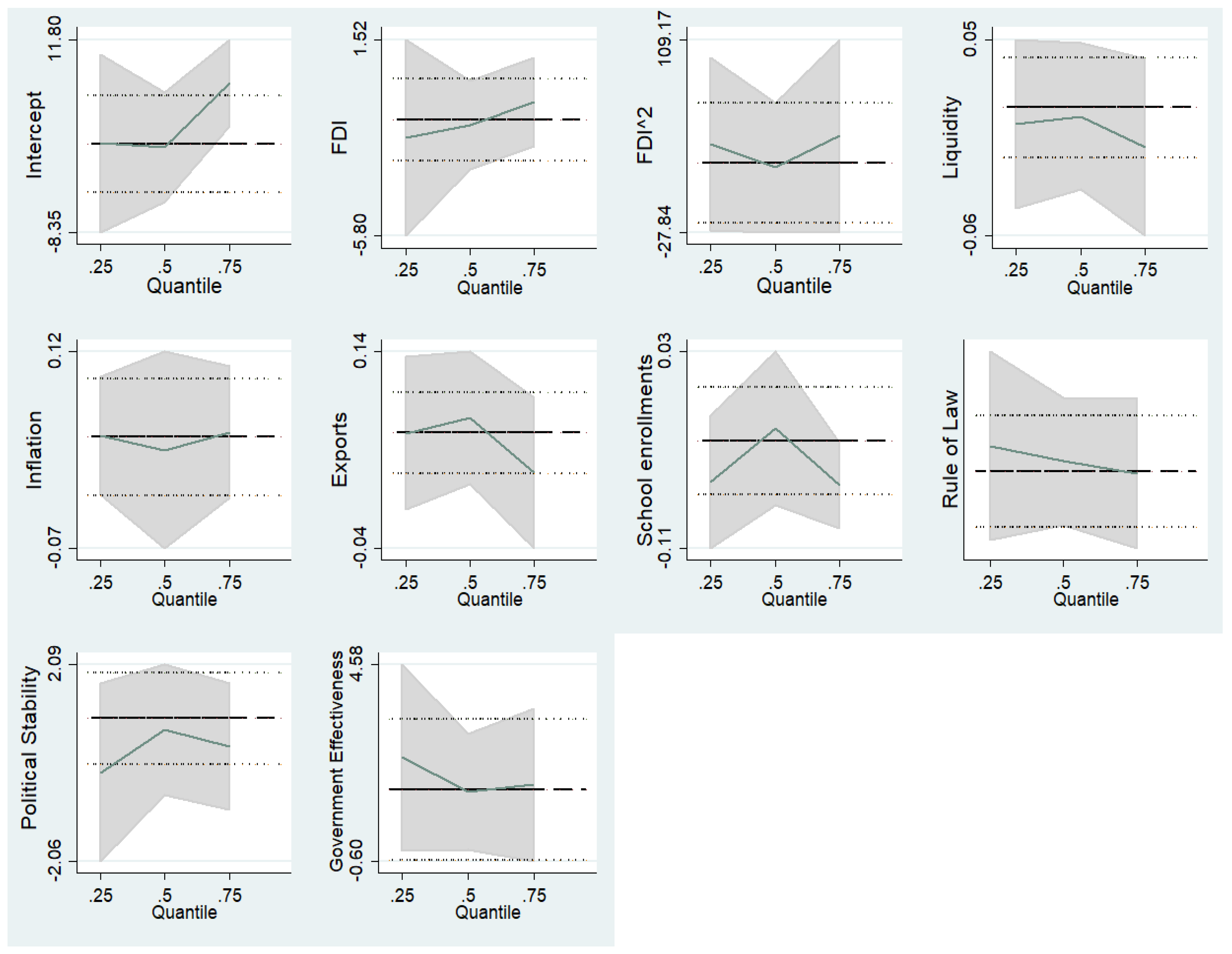

In addressing these critical questions, this study built upon previous research, with significant implications for financial industry policies. In addition, they provide valuable insights regarding how variations in financial conditions in MENA economies impact the advantages of financial institutions and financial markets. To accomplish this, we performed a comparison of linear and nonlinear dynamic panel GMM models of financial development, considering both financial institution and financial market indicators to analyze the “vanishing effect” of financial development. Our initial findings suggested that financial development generally promotes economic growth, but the relationship between financial development and growth is not straightforward. Re-evaluating the non-monotonic hypothesis may reveal empirical evidence that supports the existence of a potential maximum financial development threshold. The growth effect of financial development, whether from financial institutions or financial markets, becomes negligible beyond this threshold. This suggests that expanding financial institutions and financial markets too much may lead to the creation of financial bubbles, causing the growth effect to disappear. Hence, it is not necessary to have a greater degree of financial development to achieve economic growth.

Furthermore, this study found that financial institutions have an insignificant impact on enhancing growth but a significant impact on restricting growth. In contrast, a critical role is played by financial markets in encouraging growth, which weakens over time and eventually negatively affects the economy. Thus, policymakers should focus on policies that prioritize the quality of finance instead of only expanding the finance sector if it is evident that further financial development significantly restricts economic growth after attaining the threshold level. However, if the data indicate that financial development significantly enhances economic growth after exceeding a given threshold level, policymakers should consider increasing financial depth by implementing stringent financial regulation so that the quality of financing is maintained.

To achieve its objectives, this study followed a systematic structure consisting of five parts. After this introductory section,

Section 2 reviews the related literature and identifies gaps, followed by empirical model specification, variable selection, and econometric approaches used.

Section 4 presents the empirical results and discusses relevant considerations, while

Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

Several models of the endogenous growth theory emerged from the 1980s that incorporated financial institutions and defined mechanisms through which financial development could impact economic growth, illustrating the impact of well-performing financial systems on saving and allocation decisions via capital accumulation and total factor productivity (

Bencivenga and Smith 1991;

Greenwood and Jovanovic 1990). Improved access to capital accumulation facilitated local and international investments, spurred by financial liberalization (

Blackburn and Hung 1998). A positive relationship between long-term economic growth and the size of the financial sector, initially demonstrated by

Goldsmith (

1969) and

King and Levine (

1993a), demonstrated that the following decades continued to exhibit a strong relationship between the level of liquid liabilities and economic growth, indicating that financial depth was a positive determinant of the latter.

Patrick (

1966) presented the “supply-leading” hypothesis that indicated a causal link between economic growth and financial development. According to this hypothesis, purposeful establishment of financial institutions and markets enhances the provision of financial services, fostering tangible economic growth. (

Nguyen et al. 2022). Researchers like

King and Levine (

1993b) and

Goldsmith (

1969) further explored the chains of this hypothesis. It has also been suggested that economic volatility can be reduced by financial development (

Beck et al. 2014).

Previous studies established a causal relationship in both directions between the development of the financial sector and economic growth (

Luintel and Khan 1999;

Calderón and Liu 2003;

Shan et al. 2001). However,

Ang and McKibbin (

2007) found evidence supporting the “demand-following” theory, suggesting that economic growth gives rise to financial development. On the other hand, the “supply-leading” theory was supported by other studies, which demonstrated that financial development drives economic growth (

Neusser and Kugler 1998;

Choe and Moosa 1999).

Graff (

2005) contributed to this body of research by highlighting three distinct perspectives regarding the causal relationship between economic growth and financial development. The first of these is the availability of a reliable and cost-effective form of payment, like coins or later banking money historically derived from fractional reserve banking (

Rousseau and Wachtel 2000;

Kindleberger 1993). The second is the volume effect, in which financial activity stimulated savings that could be channeled into investment (

Ali et al. 2021). Finally, the third perspective is the allocation effect, which led to the more efficient allocation of resources for investment (

Purewal and Haini 2021). The conclusion drawn from these studies was that it was advisable to pursue the idea of “more finance, more growth” (

Roodman 2009a). However, it is important to note that these studies assumed a linear relationship between economic growth and financial development that remained constant over time.

Deidda and Fattouh (

2002) revealed the presence of a nonlinear relationship between finance and economic growth, demonstrating that, in economies with a high initial per capita income, financial development had a positive and substantial effect on economic growth once a certain threshold was surpassed. However, in nations with a low initial per capita income, there was no statistically significant association between financial development and growth (

Appiah et al. 2023). On the other hand, in intermediate-income nations, the link between financial development and growth was significant and sizable (

Rioja and Valev 2004a). The effects observed in high-income countries were positive but very minor. They also observed that, in general, the impact of financial development on economic growth was positive, but it varied based on the level of development (

Rioja and Valev 2004b). On the other hand,

Graff (

2005) showed that if countries diverge from a path of sustainable development, then the benefit they receive from a given amount of financial activity is comparatively less. Similarly,

Huang and Lin (

2009) used threshold regression with instrumental variables, provided by

Caner and Hansen (

2004), and a positive relationship between financial development and economic growth was determined. They noted that the positive impact was more significant in low-income nations in comparison to high-income nations. Interestingly, these studies used interaction models instead of quadratic models, despite them implying nonlinearity in the relationship between economic growth and financial development. In the research of

Tsagkanos et al. (

2021), they investigated the impact of financial development on stock market volatility. To measure the volatility effect on financial development, they would typically specify an econometric model that relate financial development and stock market volatility. They used statistical techniques that accounted for potential explanatory variables and controlled for other factors that can affect volatility, such as macroeconomic conditions or growth.

The literature presents inconsistent evidence regarding the relationship between financial development and economic growth, with some studies showing positive effects and others indicating negative effects (e.g.,

Schularick and Taylor 2012;

Kaminsky and Reinhart 1999). Some studies explained that financial depth and economic growth had a positive long-term relationship, but one which was negative in the short term (

Loayza and Ranciere 2006). Additionally,

Broner and Ventura (

2010) attributed this to the pro-cyclical nature of the financial sector, where financial liberalization did not sustain the increase in economic growth. Due to these inconsistent findings, academics and policymakers were motivated to review the “more finance, more growth” proposition and identify the optimal level of financial development that encourages economic growth.

Shen and Lee (

2006) identified patterns of nonlinearity in the form of an inverted U-shaped link between financial development and growth.

Cecchetti and Kharroubi (

2012),

Arcand et al. (

2015), and

Law and Singh (

2014) performed further studies that demonstrated a nonlinear relationship between finance and growth, characterized by an inverted U-shaped or Kuznets curve. This suggests that financial development can increase economic growth up to a specific point (

Azman-Saini et al. 2010). However, if it exceeds the threshold level, then economic growth slows down because of the negative effect of the nonlinear nexus between finance and growth because of the “vanishing effect” (

Arcand et al. 2015).

Law and Singh (

2014) proposed the hypothesis that “too much finance harms economic growth” based on this inverted U-shaped nexus.

Various techniques were used to assess the nonlinear relationship between finance and economic growth. Semi-parametric estimation was used by

Arcand et al. (

2015) with panel data of 100 developing and developed nations between the years 1960 and 2010.

Cecchetti and Kharroubi (

2012) used (OLS) to examine the nonlinear nexus in panel data for 50 countries for five-year periods between 1980 and 2009.

Law and Singh (

2014) addressed the endogeneity issue using a dynamic panel threshold formulated by

Kremer et al. (

2013). After this, they employed a dynamic GMM estimator for a quadratic model to increase the reliability of their findings. A quadratic model was employed by

Samargandi et al. (

2015) to evaluate the nonlinear nexus between growth and finance, employing panel data from 52 middle-income nations from 1980 to 2008.

This study aimed to address several gaps in the available literature by employing a nonlinear technique to identify changes in the relationship between finance and EG. First, it focused on data from the period of 1996–2022, providing insights into the recent economic conditions and assessment of the efficacy of financial development in MENA countries. Second, it investigated the consistency of the previously observed inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and financial development. Lastly, this study examined whether there are any discernible variations in the effects of financial institutions and financial markets on economic growth. To achieve these objectives, the paper utilized the U-test of

Sasabuchi (

1980) and

Lind and Mehlum (

2010) to confirm that the finance–growth relationship had a nonlinear pattern. Additionally, the two-step system GMM estimator was employed to estimate the quadratic model. The focus of this research was restricted to MENA countries, as financial development is a crucial element for economic growth, and it is essential for all countries aspiring to achieve development to have this.

5. Conclusions

Linear and nonlinear correlations were evaluated in this study across 17 countries within the MENA region spanning 26 years (1996–2022). The objective was to assess how financial development affected economic growth within MENA. The primary focus was shedding light on the nuanced association between financial development and growth and exploring the contributions of governance frameworks and macroeconomic indicators to the relationship between them.

Based on earlier empirical outcomes derived from a linear model, economic growth exhibited a positive correlation with financial development indices. However, the outcomes took a different direction when a nonlinear model was introduced, revealing a nonlinear connection between financial development and economic growth. The basis of the hypotheses of the U-test was a previous estimation (

Lind and Mehlum 2010). This study’s findings, which counter the earlier concept suggesting the temporary harm of excessive finance on economic growth, underscore the presence of a nonlinear, U-shaped relationship between financial development and economic growth within MENA countries. The analysis specifically identified the presence of a normal distribution or an inverted U-shaped curve at the intersection of financial development and EG. While the enhancement of the financial sector can considerably enhance a country’s economy, this positive impact can also be offset by weak or unstable regulatory frameworks, leading to negative consequences.

Governance practices and relevant macroeconomic indicators were used in this research, and these aid policymakers in comprehending their potential influence on EG. The findings of this study could also offer valuable insights for managers, specifically within the MENA region, seeking to discern the factors affecting financial development and to gain a deeper understanding of such dynamics. Furthermore, this paper illustrates that the level of economic regulations and macroeconomic variables, like inflation (

Yilmazkuday 2011) and regulations influencing the financial sector (

Abiad and Mody 2005), act as crucial determinants in shaping the effect of financial development on EG. This interdependence underscores the susceptibility of the role played by finance in driving EG.

The results of this study can serve as valuable guidance for policymakers and those in the financial sector management, aiding them in formulating effective financial policies, regulations, and frameworks that foster the positive contribution of the financial sector to overall economic development. This research emphasizes the significance of enhancing the financial sector’s quality alongside supporting its development as part of stimulating EG. This underscores the importance of a dual approach, whereby financial rules are simultaneously broadened and strengthened, accompanied by enhanced oversight and control of financial activities. This approach aims to ensure that financial development positively affects economic growth and curtails the “vanishing effect”. Furthermore, this study aligned with the notion of “more and better finance, more growth”, taking into consideration the quantity as well as the quality of financial resources.

This paper substantiated and strengthened the outcomes by suggesting that researchers conduct additional investigations that encompass a broader range of regions or countries, while also considering a wider array of control variables or alternative governance indicators.