Abstract

Financial recording is still difficult due to the limited knowledge of farmers, whereas financial recordings are crucial for producing important reports for business development. This study aims to analyze the factors related to farmers’ activity in recording farm finances and the impact on farmers’ production and income. The study was carried out in West Java and included 200 potato farmers in the Garut and Bandung Districts. Factors related to the farmers’ experiences recording farm finances were investigated using logistic regression analysis. The results of this study showed that the significant factors related to farmers’ activity recording farm finances are the farmers’ education, their participation in the training of financial records, and their experience in obtaining finance from farmers’ associations, traders and agricultural input kiosks. Furthermore, this study also showed that recording financial transactions in agricultural business can increase farmers’ production and income. This study provides insights to policymakers and financial providers, showing the need to provide farmers with assistance in financial recording.

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector has gained the attention of the Indonesian government regarding its economic development. The government and society expect the agricultural sector to develop in a more positive and promising direction in terms of income, profits, and business expansion. This positive development is inseparable from the need for financing. Appropriate financial management can be assessed using financial records. This is still an obstacle to the development of agricultural businesses, because business actors cannot properly record agricultural finances, whereas the agricultural business sector has enormous potential to improve the community’s quality of life. Business actors in Indonesia, who are generally still categorized as small businesses, play a significant role in national production, employment, and improving the Indonesian economy (Andarsari and Dura 2018).

In general, the implementation of accounting activities in small businesses in Indonesia includes financial records in the form of income and expenditure reports, which are limited to controlling the business (Andarsari and Dura 2018). Many small business actors were not able to present detailed financial data and information. Moreover, financial information and data have not been fully used as a basis for decision making, such as in production or sales activities (Yushita 2014).

Financial records in small businesses are still limited to income and expenses, in which the difference is considered as profit, even though many other factors can be applied to determine profit. This could be due to the unknown benefits and importance of implementing financial reports and bookkeeping in the development of a business (Rizal et al. 2019).

The majority of agricultural business actors performed manual financial recording. The financial recording process is part of the accounting process. When business actors plan to maintain their businesses in the long term, financial records should not be ignored; thus, every transaction that occurs can be clearly identified (Andarsari and Dura 2018). Related to the financial recording system, a study from Grefalde (2019) revealed that manual and computer program increased convenience and led to faster recordings of financial transactions. The study also showed that business actors maintained a manual record system; however, computers were still used because they have faster and easier functions and also facilitate the generation of financial reports. In addition to the financial record system, the sole proprietorship and partnership business actors were recorded in a computerized system without accounting software (Lisjanto and Darmansyah 2018). The survey of OJK Directorate of Microfinance Institutions found that manual financial recording was still be used by many Microfinance Institutions with a makeshift book (Iswoyo et al. 2019).

Financial recording is crucial to the production of important reports for business development. Financial statements can be used, for instance, as a condition of applications for business capital loans to financial institutions. As Mwebesa et al. (2018) revealed, the financial record is an important practice in the tracking of debtor records, which leads to profit. However, financial records are still difficult to produce due to the limited knowledge of accounting science and the complexity of the accounting process (Savitri and Saifudin 2018). This may cause many business actors, including farmers in Indonesia, to not keep financial records for their farms (Anggreany et al. 2016).

This study aims to analyze the factors related to farmers’ records of farm finances and the impact on farmers’ production and income. Several literatures have discussed financial record keeping (Tham-Agyekum et al. 2010; Dudafa 2013; Mwebesa et al. 2018). However, the study of farm financial recording in relation to access to various financial sources has not yet been conducted. Therefore, this study contributes to prior literature by linking the experience in obtaining financing from various sources of finance with the farm financial recording.

2. Research Method

This study focuses on the potato commodity because potatoes, as a commodity, are continuously developed by the Indonesian government. The study included 200 potato farmers and was carried out from July to November 2020 in West Java, especially in the Garut and Bandung Districts, as these two districts are centers of potato production in Indonesia. This study applied simple random sampling. The two sub-districts with the highest potato production for each district were determined, i.e., the Pasirwangi and Cikajang Sub-districts in Garut District, and the Pangalengan and Kertasari sub-districts in Bandung District.

Supporting letters for this study, provided by Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia, were used to survey farmers. Study permission was obtained from the agricultural offices in the study areas. Following a similar procedure from a study by Reyes-García et al. (2016), prior to the interviews, oral consent was obtained from the farmers, because some of them had little schooling. The purpose and contents of this study were introduced to the farmers before beginning the survey. The participation of farmers was voluntary and anonymity was assured.

The data collection techniques in this study used questionnaires, interviews and literature studies. The variables included farmers’ demographics, social and economic variables, such as age, gender, education, farming experience, farm size, production, experience in recording farm financial information, experience with financial record training, participation in agricultural extensions, and experience in obtaining finance from various sources.

Age is measured as the age of the farmer in years and is expected to have a positive relation with financial record activity, as farmers’ age positively affects their financial management (Silva and Malaquias 2020). Gender is a dummy variable and is expected to have an association with financial record activity, because gender has a different effect on financial literacy (Ahmadi and Sulistyowati 2019). Education is measured as the formal education of a farmer in years. Education is expected to positively relate to financial record activity, as education has a positive effect on interest in accounting records (Yanto et al. 2019). Farming experience is measured as the number of years of experience in managing a farm. Farming experience is expected to positively affect financial record activity because experienced farmers have more knowledge about their farms and farming practices (Ayaz and Hussain 2011).

Farm size is measured as the size of the area managed by a farmer in the production of crops. Farm size is expected to positively affect financial record activity, as large farms tend to prioritize financial management (Lai et al. 2019). Production is measured as potato production in kilograms and is expected to positively relate to financial record activity, as accounting records relate to control spending costs, which, in turn, affect production (Al-Sharafat 2016). Financial record training is a dummy variable, which is expected to have a positive association with financial record activity.

Participation in agricultural extension is the number of farmers’ participation in agricultural extension, and is expected to have a positive association with financial record activity. Agricultural extension can enhance the independence of farmers (Haryanto and Yuniarti 2017; Camillone et al. 2020), which, in turn, may affect farmers’ habit of recording financial activity.

Regarding experience with obtaining finance, finance can be accessed from several financial sources, such as credit from banks and micro-finance institutions (MFI), in kind finance from government through farmers’ associations, in kind finance from traders, finance in the form of flexible payments from agricultural input kiosks, and credit from family and friends (Wulandari et al. 2021). The different financial sources are expected to have a positive relation with financial record activity, as a higher proportion of farmers who kept records obtained credit (Tham-Agyekum et al. 2010).

In this study, factors related to the farmers’ experience recording farm finances were investigated using logistic regression analysis. The logistic equations are as follows:

where:

Y = Financial record activity (Y = 1 if a farmer recorded his/her farm financial transaction; Y = 0 otherwise).

= Constanta.

= Coefficient.

= Age (years).

= Gender (1: male; 0: female).

= Education (years).

= Farming experience (years).

= Farm size (hectare).

= Production (kilograms).

= Financial record training (1: have attended financial record training; 0: otherwise)

= Agricultural extension frequency (numbers).

= Bank (1: have obtained credit from bank; 0: otherwise).

= MFI (1: have obtained credit from MFI; 0: otherwise).

= Farmers’ association (1: have obtained inkind finance from farmers’ association; 0: otherwise).

= Trader (1: have obtained in kind finance from trader; 0: otherwise).

= Agricultural input kiosk (1: have obtained flexible payment from agricultural input kiosk; 0: otherwise).

= Family and relatives (1: have obtained credit from family and relatives; 0: otherwise).

To analyze the impact of recording financial transactions, Hotelling’s T2 test was performed. The formula for the test is as follows:

in which the

where:

n: number of data.

: vector mean of the population.

: vector mean of sample x.

S: covariance matrix.

3. Results

Agriculture is a major economic contributor to Indonesia, particularly in providing employment for the Indonesian population (Widyawati 2017). Potato is an important food as it is one of the alternative staple foods in Indonesia (Widyanti et al. 2014). Furthermore, potatoes contain mineral, protein, vitamins and other benefits (Love and Pavek 2008; Burlingame et al. 2009; Tian et al. 2016).

Despite the importance of financial recordings in reducing business costs (Coulson et al. 2021), many agricultural business actors often kept manual financial records due to their traditions or habits, and many of them did not keep records at all. This is because business actors assumed that financial records would be complicated. Many people would like to start a digital financial record for their business transactions, but do not understand how to use digital media as a means of recording and digitizing finances. The farmers’ descriptions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The description of farmers.

Regarding the results of the analysis in Table 1 the youngest farmer is 20 years old and the oldest is 76 years old, with an average age of 46 years, which is a productive age to work. At a productive age, his/her motivation, ability and skills at work tend to be good. Vecchio et al. (2020) stated that age influences farmers’ behavior, as younger farmers tend to be more involved in more innovative farming.

The gender of farmers is dominated by men by as much as 94%. In general, the productivity level of men is higher than that of women. This may be influenced by women being physically less strong (Bullough and Renko 2017), or tending to use their feelings or emotions at work (Naudin and Patel 2019). The majority of farmers are only primary school graduates, at around 40%, with farmers having an average education of 9 years. Farmers are often characterized by their low levels of education, which is an inhibiting factor for technological innovations in society. Education will generally contribute to a person’s mindset, making it more dynamic. For instance, a study by Wang and Cao (2022) emphasized the more innovative financial services offered by banks with a higher average education level and more financial or accounting backgrounds among directors. Furthermore, highly educated farmers are relatively quick to understand the use of new technology. As Salazar and Rand (2016) noted, more educated farmers are more likely to adopt new technology.

The average farming experience of farmers is 20 years. According to Soeharjo and Patong (1973), farming experience is divided into three categories: less experienced (less than 5 years), moderately experienced (between 5 and 10 years), and experienced (more than 10 years). With regard to this categorization, the average experience of farmers in this study categorized them as experienced farmers. Farming experience affects a person’s way of managing his farm. Experienced farmers will be more selective and precise in choosing the types of innovation that will be applied. Experienced farmers will also be more careful in the decision making process, while less experienced farmers will usually make decisions faster because they are more willing to take risks.

The average land area of the respondents was 0.55 hectares. According to Soekartawi (1989), the land area was grouped into three levels: narrow (land area less than 0.5 hectares), medium (land area between 0.5 and 0.8 hectares), and broad (land area more than 0.8 hectares). With regard to this categorization, the average land area managed by farmers is in the medium category. The average production of farmers is 13,337 kg of potatoes.

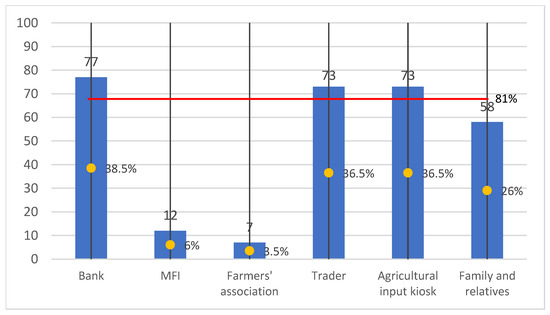

Experience in obtaining financing is another factor that can affect a business’ financial recording activities. Table 1 shows that the majority of farmers received financing from various sources. According to Wulandari et al. (2020), access to finance is very influential in farm production. Experience in obtaining access to finance from various sources is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experience in obtaining finance.

Figure 1 shows that the majority of the farmers (81%) obtained finance from at least one financial source. Among the different sources of finance, the bank was the most accessed by the farmers (38.5%), while trader and agricultural input kiosks accounted for 36.5% of each source.

Regarding the financial record activity, Table 1 shows that only 51% of farmers recorded financial transactions in their farm businesses. When creating financial records of their business, farmers kept records by writing down financial transactions in a book. Many farmers did not record their finances because they did not have the free time needed to make the recording. Financial records were often limited to simple records of financial expenses and income. Manual records were often incomplete and not in accordance with the existing standards of the Financial Accounting Standards for Micro, Small, and Medium Entities; thus, the recordings did not produce complete and reliable financial reports (Andarsari and Dura 2018). This will certainly impact the quality of managerial decision making (Yaftian et al. 2017). Most administrative systems for recording financial statements are still manual and use a simple method, such as recording in notebooks and calculating manual transaction data, to produce financial reports and for simple bookkeeping. Financial record keeping, for some enterprises, can be considered a waste of time (Smirat 2013). The high number of transactions that occur each day require recording, as well as the calculation of transactions and creation of reports, which can take a lot of time (Juhardi and Khairullah 2019). Some people faced a financial crisis; for example, they always felt lacking in income. This crisis was not actually due to a lack of income, but inappropriate financial arrangement (Muhtar 2015). For instance, the calculation of profit or loss was often manually calculated using the selling price minus the purchase price. This formula is intended to find a mean to obtain the gross profit or loss because other costs, such as salaries, gasoline and printing costs, are not deduced. Difficulties in determining profit or loss for a certain period, messy recordings, and obstacles when analyzing costs are mainly caused by a lack of understanding. In addition, farmers often complained that their business and personal finances were often mixed. This is highly detrimental, as poor financial management leads to difficulties in properly controlling finances. Failure to manage personal finances can have serious long-term social consequences (Perry and Morris 2005). Inaccurate financial reporting due to the complexity of the calculations affects the difficulties in providing a financial statement (Hirst et al. 2003).

On average, farmers attended agricultural extensions in their area once a month. Extension programs can offer farmers education and training in the form of non-formal education, which, in turn, can improve farm management abilities (Mayombe 2018). Thus, the main objective of agricultural extension is to increase farmers’ ability to obtain the maximum possible production.

Training in record keeping is essential to maintain complete and accurate business records (Abdul-Rahamon and Adejare 2014). The results of the analysis showed that only 38.5% of farmers participated in financial record training. This can lead to ignorance regarding detailed financial analyses of the business. Financial record training can improve their financial literacy, which is very important for running their businesses. Financial literacy includes general financial concepts, financial records, and financial management skills (Rohayati et al. 2020), the ability to distinguish between personal and business expenses, and the ability to make decisions related to finance (Drexler et al. 2014). Proper financial records can lead to good decisions regarding business, such as decisions on whether to maintain product lines, expansion, and so on which, in turn, enhance business performance (Abdul-Rahamon and Adejare 2014). The existence of good financial records can make entrepreneurs more rational in determining the selling price, as well as the selection of raw materials (Sucuahi 2013). Factors related to farmers’ records of their farm finances are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors related to farmers’ records of their financial agricultural businesses.

Regarding the results of the analysis in Table 2, the most significant factors related to farmers’ recording of their farm finances are their education, experience with recording financial training, and access to finance from farmers’ associations, traders and agricultural input kiosks.

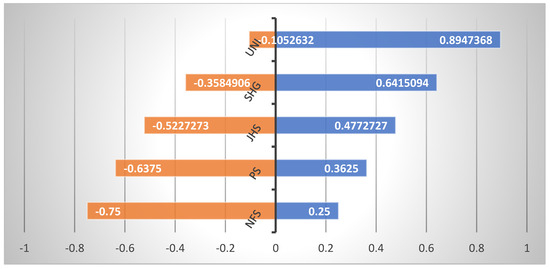

The variable of education has a significant and positive relationship with farmers’ recording of farm finances, meaning that farmers with a higher level of education tend to record their farm finances. The value of the marginal effect of education is 0.080, which means that if education increases by 1 year, the probability that farmers would keep financial records would increase by 0.080, or 8%. Figure 2 presents how the level of education is associated with farmers’ activities in recording business finances. From Figure 2, it can be seen that the majority of farmers who recorded farm finances are farmers with a university education. Meanwhile, many farmers that graduated from primary school did not record their business finances.

Figure 2.

The level of education associated with farmers’ financial records. Note: no formal school (NFA); primary school (PS); junior high school (JHS); senior high school (SHS); university (Uni).

The variable of financial record training has a significant and positive relationship with farmers’ activities recording farm finances. This indicates that farmers who attended financial recording training are more willing to record their farm finances. The value of the marginal effect of recording training is 0.627, which means that the probability that farmers will carry out financial recording if they receive recording training would be 0.627, or 62.7% higher than the farmers who never received training. Training can impact farmers’ intentions as well as their attitudes and actions (Lobley et al. 2013).

The results also show that variables of experience obtaining financing from farmers’ associations, traders and agricultural input kiosks have a significant and positive relationship with farmers’ activities recording farm finances. This indicates that farmers who receive financing from these financial sources tend to record their farm finances. The value of the marginal effect of access to finance from farmers’ associations, traders and agricultural input kiosks are 0.498, 0.308 and 0.168, respectively, which means that the probability that farmers will keep financial records if they receive financing from these financial sources would be 49.8%, 30.8% and 16.8% higher, respectively, than if the farmers did not receive financing from these financial sources. The impact of the farmers’ records of their farm’s financial transactions on their production and income is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hotelling’s T2 Test Results.

Regarding the analysis presented in Table 3, farmers who recorded their farm’s financial information had a higher average production and income than farmers who did not record this information. The difference in average income between farmers who recorded their financial information and their counterparts was IDR 1,930,807. Univariately, differences regarding income and recorded financial activities were at the 95% significance level. The production of recorded activities did not show a significant difference at the 95% level because the p value was more than the real level (0.486 > 0.05). The difference in the average production of farmers who recorded their finances compared with the ones who did not record was 2244.44 kg.

Table 4 shows that the model in this study has a significant impact on production and income. The p-value of 0.002 is less than the 0.05 level of significance, implying a significant difference in the average production and income between farmers who recorded their financial transactions and those who did not. This indicates that recording financial transactions in the agricultural business can significantly increase production and income. This may be because by keeping financial records, farmers can determine their expenses when buying input in production activities. The implication is that business can take place efficiently, which, in turn, optimizes crop yields and increases farmers’ income.

Table 4.

Multivariate Hotelling’s T2 Test Results.

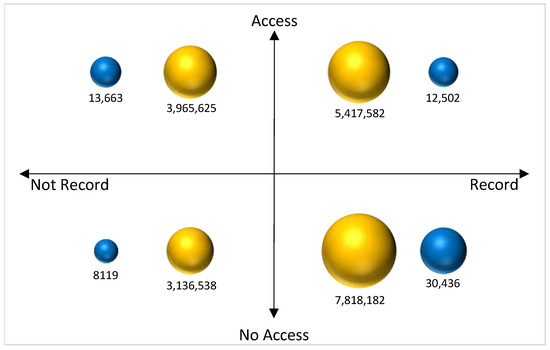

Figure 3 shows estimated average marginal income and production in terms of financial recording and access to finance. Figure 3 shows that differences in income and production exist between farmers who kept financial records and had access to finance and those who did not. The highest income and production levels were obtained by farmers who recorded their farm finances but did not have access to finance. The lowest income and production levels were obtained by those who neither practiced financial recording nor had access to finance. This implies that financial recording tends to increase farmers’ income and production. The percentage of income increased by 149%, from IDR 3,136,538 to 7,818,182, while production increased by 275%, from 8119 to 30,436 kg. Farmers who previously neither recorded farm finances nor had access to finance, and then later obtained access to finance, experienced an increase in income and production of 26% and 68%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Estimated average marginal income and production on financial recording and access to finance. Note: Yellow = income, blue = production.

Something interesting happened to the group of farmers who kept records and had access to finance compared with the farmers who kept records but did not have access to finance. The groups of farmers who kept records and had access to finance and the farmers who kept records but did not have access to finance had lower income and production levels. However, those groups had the highest income among the other two groups. They could earn IDR 433,337 per kilogram, which was 69% higher than the farmers who did not have access to finance. This means that by recording their farm finances farmers can properly manage every resource they have, leading to a large increase in income. Furthermore, farmers with access to finance can obtain an optimal income. With a combination of those conditions (recording farm finances and having access to finance), farmers not only can obtain a high income, but can also optimize the income that can be earned from the production activity.

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Many agricultural business actors, including farmers, kept manual financial records due to habit and some did not record at all. Factors related to farmers’ experience recording farm finances were investigated using logistic regression analysis. The results of this study showed that the most significant factors related to farmers’ activities in recording farm finances are farmers’ education, their participation in financial record training, and experience obtaining finance from farmers’ associations, traders and agricultural input kiosks. This study also indicates that recording the financial transactions of agricultural businesses can increase farmers’ production and income.

As a part of implication, this study shed light on the need for providing the assistance of farm financial recording for policymakers and financial providers. Although the study was performed to the highest standard, it also has limitations, as the target participants included only farmers. Future research may include other parties who are involved in agricultural businesses, including government and financial providers related to encouraging farmers’ activity of financial management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.W.; methodology, E.W. and R.T.P.A.; validation, E.W., T.K. and E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.W.; writing—review and editing, E.W., T.K., E. and R.T.P.A.; supervision, E.W., T.K. and E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are gratefully acknowledging all the potato farmers who have participated in this study. The authors also thank to Universitas Padjadjaran for the financial support of this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Study permission was obtained from the agricultural offices in the study areas.

Informed Consent Statement

Oral consent was obtained from the respondents.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from Director of Research and Community Services Universitas Padjadjaran in the preparation of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdul-Rahamon, O. Adekunle, and Adegbite Tajudeen Adejare. 2014. The analysis of the impact of accounting records keeping on the performance of the small scale enterprises. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 4: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Herman, and Liliek Nur Sulistyowati. 2019. The effect of socioeconomic status and gender on financial literacy (experimental study on MSMEs in Madiun). Widya Warta 1: 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sharafat, Ali. 2016. The Impact of the use of agricultural accounting on the financial performance of broiler industry: A comparative evaluation approach on broiler industry in Jordan. Journal of Agricultural Science 8: 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andarsari, Pipit Rosita, and Justita Dura. 2018. Implementation of financial records in small and medium enterprises. Jurnal Ilmiah Bisnis dan Ekonomi Asia 12: 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggreany, Shinta, Pudji Muljono, and Dwi Sadono. 2016. Participation of farmers in the replanting of palm oil in the Jambi Province. Jurnal Penyuluhan 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, Saima, and Zakir Hussain. 2011. Impact of institutional credit on production efficiency of farming sector: A case study of District Faisalabad. Pakistan Economic and Social Review 49: 149–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, Amanda, and Maija Renko. 2017. A different frame of reference: Entrepreneurship and gender differences in the perception of danger. Academy of Management Discoveries 3: 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, Barbara, Beatrice Mouillé, and Ruth Charrondiere. 2009. Nutrients, bioactive non-nutrients and anti-nutrients in potatoes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 22: 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillone, Nina, Sjoerd Duiker, Mary Ann Bruns, Johnson Onyibe, and Akinwumi Omotayo. 2020. Context, challenges, and prospects for agricultural extension in Nigeria. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education 27: 144–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, Andrea B., Michael O. Rivett, Robert M. Kalin, Sergio M. P. Fernández, Jonathan P. Truslove, Muthi Nhlema, and Joseph Maygoya. 2021. The cost of a sustainable water supply at network kiosks in Peri-Urban Blantyre, Malawi. Sustainability 13: 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, Alejandro, Greg Fischer, and Antoinette Schoar. 2014. Keeping it simple: Financial literacy and rules of thumb. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudafa, Undutimi Johnny. 2013. Record keeping among small farmers in Nigeria: Problems and prospects. International Journal of Scientific Research in Education 6: 214–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grefalde, James Quińonez. 2019. Bookkeeping practices of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). The International Journal of Business and Management 7: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, Yoyon, and Wiwik Yuniarti. 2017. The role of farmer to farmer extension for rice farmer independence in Bogor. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences 7: 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, D. Eric, Kevin E. Jackson, and Lisa Koonce. 2003. Improving financial reports by revealing the accuracy of prior estimates. Contemporary Accounting Research 20: 165–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswoyo, Andi, Yuli Ernawati, Alfi Nugroho, and Sasangko Budi Susetyo. 2019. Development of Financial Statement Applications for SMEs based on Financial Accounting Standards for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. Paper presented at the International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management, and Social Science, Bali, Indonesia, October 10–11; pp. 173–80. [Google Scholar]

- Juhardi, Ujang, and Khairullah Khairullah. 2019. Financial recording and processing system in android-based e-wallet financial management application. Journal of Technopreneurship and Information System 2: 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, John, Nicole J. Olynk Widmar, and Christopher A. Wolf. 2019. Dairy farm management priorities and implications. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 22: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisjanto, Fionna Griseldis, and Asep Darmansyah. 2018. Comparative analysis of bookkeeping at sole proprietorship and partnership small and medium enterprises: Study on culinary sector in Greenville, Jakarta. Scientific Research Journal VI: 2009–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lobley, Matt, Eirini Saratsi, Michael Winter, and James Bullock. 2013. Training farmers in agri-environmental management: The case of Environmental Stewardship in lowland England. International Journal of Agricultural Management 3: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Love, Stephen L., and Joseph J. Pavek. 2008. Positioning the potato as a primary food source of vitamin C. American Journal of Potato Research 85: 277–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayombe, Celestin. 2018. From social exclusion to adult education and training for community development in South Africa. Community Development 49: 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtar, Muthmah Sutrisna. 2015. Android-Based Personal and Household Financial Management Application. Doctoral dissertation, UIN Alauddin Makassar, Makassar, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Mwebesa, Lawrence Collins Kihamaiso, Catherine Kansiime, Benon B. Asiimwe, Paddy Mugambe, and Innocent B. Rwego. 2018. The effect of financial record keeping on financial performance of development groups in rural areas of Western Uganda. International Journal of Economics and Finance 10: 136–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudin, Annette, and Karen Patel. 2019. Entangled expertise: Women’s use of social media in entrepreneurial work. European Journal of Cultural Studies 22: 511–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Vanessa G., and Marlene D. Morris. 2005. Who is in control? The role of self-perception, knowledge, and income in explaining consumer financial behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs 39: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, Victoria, Aili Pyhälä, Isabel Díaz-Reviriego, Romain Duda, Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, Sandrine Gallois, Maximilien Guèze, and Lucentezza Napitupulu. 2016. Schooling, local knowledge and working memory: A study among three contemporary hunter-gatherer societies. PLoS ONE 11: e0145265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizal, Muhamad, Erna Maulina, and Nenden Kostini. 2019. Fintech as one of the financing solutions for MSMEs. AdBispreneur: Jurnal Pemikiran dan Penelitian Administrasi Bisnis dan Kewirausahaan 3: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohayati, Suci, Budi Eko Soetjipto, Agung Haryono, Hari Wahyono, and Siti Sri Wulandari. 2020. The effect of financial literacy knowledge on the finance management of farmers “Siwalan” in East Java. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 24: 2230–36. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, César, and John Rand. 2016. Production risk and adoption of irrigation technology: Evidence from small-scale farmers in Chile. Latin American Economic Review 25: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitri, Rosita Vega, and Saifudin. 2018. Accounting recording in micro, small and medium enterprises (Study on Mr. Pelangi UMKM Semarang). JMBI UNSRAT (Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen Bisnis dan Inovasi Universitas Sam Ratulangi) 5: 117–25. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Altieres Frances, and Rodrigo Fernandes Malaquias. 2020. Factors associated with the adoption of financial management practices by farmers in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Revista de Educação e Pesquisa em Contabilidade 14: 328–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smirat, Belal Yousef Al. 2013. The use of accounting information by small and medium enterprises in south district of Jordan (An empirical study). Research Journal of Finance and Accounting 4: 169–75. [Google Scholar]

- Soeharjo, and Patong. 1973. Main Joints of Farming. Jurusan Ilmu Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian. Bogor: Penerbit Institut Pertanian Bogor. [Google Scholar]

- Soekartawi. 1989. Basic Principles of Agricultural Economics. Jakarta: Rajawali Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sucuahi, William T. 2013. Determinants of financial literacy of micro entrepreneurs in Davao City. International Journal of Accounting Research 42: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham-Agyekum, Enoch Kwame, Patrick Appiah, and Fred Nimoh. 2010. Assessing farm record keeping behaviour among small-scale poultry farmers in the Ga East Municipality. Journal of Agricultural Science 2: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Jinhu, Jianhu Chen, Xingqian Ye, and Shiguo Chen. 2016. Health benefits of the potato affected by domestic cooking: A review. Food Chemistry 202: 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, Yari, Giulio Paolo Agnusdei, Pier Paolo Miglietta, and Fabian Capitanio. 2020. Adoption of precision farming tools: The case of Italian farmers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lie-Huey, and Xin-Yuan Cao. 2022. Corporate governance, financial innovation and performance: Evidence from Taiwan’s Banking Industry. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyanti, Ari, Indryati Sunaryo, and Asteria Devi Kumalasari. 2014. Reducing the dependency on rice as staple food in Indonesia–A behavior intervention approach. Journal of ISSAAS 20: 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Widyawati, Retno Febriyastuti. 2017. Linkage analysis of agricultural sector and effect on the economy in Indonesia (input-output analysis). Jurnal Economia 13: 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, Eliana, Dika Supyandi, and Ernah. 2020. The risk measurement of horticultural price: A comparison based on financial access in West Java, Indonesia. Sains Malaysiana 49: 713–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, Eliana, Miranda P. M. Meuwissen, Maman H. Karmana, and Alfons G. J. M. Oude Lansink. 2021. The role of access to finance from different finance providers in production risks of horticulture in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 16: e0257812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaftian, Ali, Soheila Mirshekary, and Dessalegn Mihret. 2017. Learning commercial computerised accounting programmes. Accounting Research Journal 30: 312–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanto, Shalihul Aziz Widya Iriawan, and Fatchur Rohman. 2019. Interest in recording accounting through education, business age, and organizational commitment to small and medium industries in Jepara Regency. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Perpajakan 5: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yushita, Amanita Novi. 2014. Financial Recording Training for Small Business. Yogyakarta: Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).