Abstract

Little is known about health professions students’ awareness and attitudes regarding public health in the United States. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess medical and pharmacy students’ knowledge and interest in the Healthy People initiative as well as perceptions of public health content in their curricula. An electronic survey was distributed in March 2021 in seven schools across Ohio; participation was incentivized through a USD 5 donation to the Ohio Association of Foodbanks to aid in COVID-19 relief efforts (maximum USD 1000) for each completed survey. A total of 182 medical students and 233 pharmacy students participated (12% response rate). Less than one-third of respondents reported familiarity with Healthy People and correctly identified the latest edition. However, nearly all respondents agreed public health initiatives are valuable to the American healthcare system. Almost all students expressed a desire to practice interprofessionally to attain public health goals. Both medical and pharmacy students recognized core public health topics in their curricula, and nearly 90% wanted more information. These findings indicate that the majority of medical and pharmacy students in Ohio believe public health initiatives to be important, yet knowledge gaps exist regarding Healthy People. This information can guide curricular efforts and inform future studies of health professions students.

1. Introduction

Although the United States (U.S.) spends more on health care per capita than any other high-income country, it reports the highest rates of infant mortality and lowest life expectancy among them. The percentage of the American adult population that is obese or has multiple chronic conditions is also higher than comparable countries [1]. Additionally, the U.S. struggles with significant health disparities based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geography [2].

The national Healthy People initiative seeks to improve health outcomes by providing a foundation for health and health promotion goals and aiming to eliminate health disparities. Healthy People is coordinated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. At the start of each decade, measurable objectives that promote health and reduce the burden of disease are published with the intent for public health and clinical health professionals to work toward those targets over the next 10 years. This future-oriented approach to improving the nation’s health and well-being began in 1979; the fifth iteration, Healthy People 2030, was released in August 2020 [3].

Healthy People provides direction for public health action by identifying the nation’s most pressing health needs. Table 1 lists the blueprint for Healthy People 2030. The latest version of Healthy People allows users of the website to set local targets for populations in their own communities based on national data [3]. As “micro” interventions in individual patients and practice settings can result in significant improvement at the “macro” level for populations, clinical health professionals play an impactful role in meeting Healthy People objectives [4]. Moreover, interprofessional collaborations among these clinical health professionals are key to reducing fragmented care, lowering health care costs, and improving health outcomes; collaborative practice agreements (CPA) between physicians and pharmacists are one such example [5,6]. Ongoing federal and state initiatives to grant pharmacists provider status and remove administrative barriers for reimbursement for clinical services can further facilitate CPA models [7,8].

Table 1.

Blueprint for Healthy People 2030 [3].

Therefore, it is important that health professions students receive adequate education and training regarding Healthy People through their professional school curricula to enable them to affect meaningful change in their future practices. To that end, the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research convened the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force (HPCTF) in 2002, a group that currently represents eight health professional education associations, including the Association of American Medical Colleges, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy [9]. The HPCTF maintains the Clinical Prevention and Population Health (CPPH) curriculum framework that suggests topics encompassing public health (i.e., protecting the health of populations) and population health (i.e., advancing health outcomes of groups of individuals) to be included in health professions education [10,11]. Health professions students must understand these distinct but intertwined areas in order to effectively provide individual- and population-oriented prevention and health promotion services [10].

To date, no studies have assessed health professions students’ awareness of Healthy People 2030 or have examined perceptions of their professional curricula in regard to instruction on the key elements of the CPPH framework. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess medical and pharmacy students’ knowledge of the federal Healthy People initiative and interest to affect its priority areas. The secondary objective was to assess students’ perception of public health content in their curricula and whether they would like more information regarding public health.

2. Materials and Methods

An electronic survey using Qualtrics software (Provo, UT) was developed to collect data from medical and pharmacy students in order to determine whether they (1) are knowledgeable of the Healthy People initiative; (2) perceive learning about certain aspects from the CPPH in their professional curricula; (3) want additional education on public health and preferred methods of instruction; (4) share common public health goals from Healthy People 2030; (5) anticipate barriers in addressing health promotion with patients; and (6) have interest in interprofessional collaboration. Selected demographic characteristics of respondents, including anticipated graduation date, were also captured.

The final surveys consisted of 35 questions for medical students and 36 questions for pharmacy students. The two surveys asked the same questions, with one additional question for the pharmacy cohort assessing interest in provider status. Question types included Likert scale, ranking, and multiple choice. The questions assessing the anticipated barriers to health promotion and related services as well as students’ preferred methods of instruction for public health content listed possible answers in a multiple-choice format and allowed for a free text response if students felt their ideas were not represented. The study was deemed exempt by the Ohio University Institutional Review Board (IRB) with the Ohio Northern University IRB agreeing that the Ohio University IRB may serve as the IRB of Record.

Prior to distribution, the survey was pre-tested to obtain feedback regarding questionnaire design and potential computer-based or technical problems by a purposive sample of medical and pharmacy residents as well as medical and pharmacy students outside of the state of Ohio who did not qualify to take the survey. Pre-test participants reported little to no survey fatigue, that instructions and questions were clear, and that they experienced no technical difficulties; therefore, no changes needed to be made to the survey.

A link to the survey was sent via email in March 2021 to students enrolled at two schools of medicine (one allopathic, one osteopathic) and five schools of pharmacy in Ohio. The email advised the student that the survey was voluntary and anonymous. To minimize potential participant bias, the email did not disclose that the focus of the survey was Healthy People and public health, but instead referred to “educational experiences and future practice plans” as the survey topic. Participation was incentivized through a $5 donation to the Ohio Association of Foodbanks to aid in COVID-19 relief efforts for each completed survey up to a maximum of $1000 due to funding constraints. Informed consent was obtained from participants via the first question of the survey. The survey remained open for 21 days, with one reminder email sent within this timeframe.

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel 2019 (Redmond, WA, USA) and IBM SPSS 25 (Armonk, NY, USA) software. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate frequencies of responses, and chi-square or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used as appropriate to identify potential differences in responses between medical and pharmacy students and between students’ year of study. Alpha was set a priori at 0.05, with the Bonferroni correction applied to the Kruskal–Wallis tests.

3. Results

A total of 182 medical students and 233 pharmacy students responded to the survey out of an estimated 3590 students who were invited to participate (12% response rate). The difference in response rate between medical students (10%) and pharmacy students (13%) was statistically significant (p = 0.019). Eighty-one percent of the surveys were completed in their entirety. As no questions in the survey were marked as mandatory, 19% of respondents left at least one question unanswered; therefore, reported percentages are calculated from the total number of respondents who answered each question.

Table 2 lists selected demographic information for respondents. Data from the six survey focus areas are grouped for discussion below into two main categories: findings related to students’ knowledge of Healthy People and perceptions of public health content in their curricula (Table 3) and findings related to students’ interest and ideas for future practice (Table 4).

Table 2.

Selected demographic characteristics of respondents.

Table 3.

Questions used to assess public health in education.

Table 4.

Questions used to assess public health in future practice.

4. Knowledge of Healthy People and Perceptions of Curricula

4.1. Awareness of Healthy People Initiative

Overall, less than one-third of all respondents reported that they were familiar with the Healthy People initiative, but pharmacy students were twice as likely as medical students to claim familiarity (39% vs. 17%, p < 0.001). Pharmacy students also more often reported learning about Healthy People in their professional school curricula (36% vs. 7%, p < 0.001). Over 90% of students were able to correctly identify the mission of Healthy People, but less than 30% could identify the current edition. There were no statistically significant differences in responses to these questions based on student year of study.

4.2. Perceived Inclusion of the CPPH in Professional Curricula

More than 70% of medical and pharmacy students agreed that they felt knowledgeable about public health-related topics. The majority of respondents either strongly or somewhat agreed that their curriculum included the four primary components of the CPPH framework (foundations of public health; clinical preventive services and health promotion; clinical practice and population health; and health systems and health policy). Survey participants also reported learning about the seven topic areas included in the Healthy People 2020 objective for health professions education (counseling for disease prevention and health promotion; cultural diversity; social determinants of health; evaluation of health sciences literature; public health systems; environmental health; global health), consistent with published end-of-decade data [12].

4.3. Desire for Additional Education on Public Health and Preferred Methods of Instruction

Respondents from both groups expressed a desire for more information about public health than their curriculum provided, with nearly 90% of medical and pharmacy students expressing at least some interest. Although there was no significant difference in wanting more information between the groups (p = 0.164), a higher percentage of medical students strongly desired more public health inclusion in their curriculum than pharmacy students (46% vs. 38%). The preferred methods for the delivery of additional information from both groups were elective courses (59%), lecture or series of lectures as part of an existing class (51%), continuing education in future practice (44%), service learning (44%), experiential learning (41%), or interprofessional exercises (32%). Least popular among students was self-directed learning (17%).

5. Interest and Ideas for Future Practice

5.1. Common Public Health Goals from Healthy People 2030

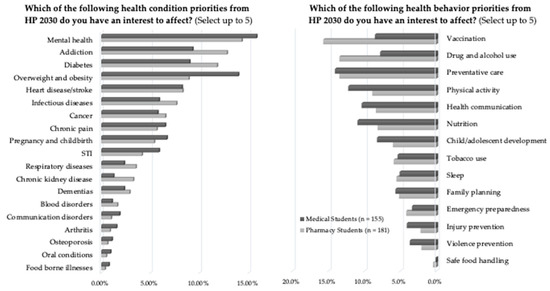

Ninety-eight percent of respondents agreed that public health initiatives are valuable to the American health care system. Both groups of students exhibited interest in affecting similar priorities from Healthy People 2030 in future practice (Figure 1). Among the five Healthy People 2030 focus areas, a higher percentage of pharmacy students ranked health conditions as most significant (p < 0.001). Medical students placed more significance on settings and systems and social determinants of health (p < 0.001). When asked specifically which determinants they thought they could impact in future practice, the most common response from both groups was health care access and quality (86%), followed by social and community support (64%), education (58%), neighborhood and built environments (50%), and economic stability (38%).

Figure 1.

Medical and pharmacy students’ interest to affect Healthy People 2030 priorities.

5.2. Anticipated Barriers in Addressing Healthy People Goals

The majority of respondents (65%) acknowledged that there would be barriers to providing health promotion and services outlined by the Healthy People initiative in their future practices. Lack of time (71%), lack of coordination with other health care providers (63%), lack of personnel and resources (60%), and lack of reimbursement (49%) were chosen as the top issues. Some students also provided free-text responses, such as “lack of universal health insurance” and “lack of patient resources (time, money, etc.) to be able to make change”. Another student pointed out that implementing certain services could be a challenge due to a lack of “government or institutional support”. Interestingly, only a small percentage of students reported lack of relevance to area of practice (12%) as an anticipated barrier. Similarly, lack of knowledge or clinical skills was not often anticipated as a barrier among respondents (17%).

5.3. Interest in Interprofessional Collaboration

When asked about the importance of working with health care providers in other professions to achieve public health goals, both groups placed almost unanimous support behind this concept. Interest in forming collaborative partnerships with each other was almost as high, with over 80% of both groups answering “strongly agree” to interest in such an opportunity. Furthermore, 96% of the pharmacy student respondents expressed interest in acquiring provider status. As a significantly higher percentage of pharmacy students than medical students selected lack of reimbursement as an anticipated barrier (57% vs. 42%, p = 0.007), obtaining provider status could help to overcome that obstacle.

6. Discussion

These findings add to the limited literature about health professions students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding Healthy People and public health goals. A majority of medical and pharmacy students surveyed believe public health initiatives are important but reported gaps in knowledge related to Healthy People. The results of this study were consistent with previous studies with emergency medicine physician residents and pharmacy residents, where over 80% and 40%, respectively, reported unfamiliarity with the Healthy People initiative [13,14].

Although actual curricular content was not assessed but rather student perceptions or recollections of content, these findings do imply that additional efforts should be made to increase awareness or retention of information regarding Healthy People among medical and pharmacy students. It is important to educate health professions students about Healthy People because, by working towards these objectives, the health of populations, resilience to public health threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and health disparities can be improved [3]. Faculty should refer to the CPPH curriculum framework as well as their discipline’s accreditation standards to ensure they are adequately preparing their students [10].

Given that few respondents identified a lack of relevance or clinical skills as potential barriers to implementing Healthy People goals, students seemed to perceive these topics as germane and felt competent in these areas. However, most students still wanted more education on public health-related topics and expressed desire to collaborate with other health care professionals. Therefore, educators should consider allocating more time to these topics, with a focus on interprofessional activities and elective courses. This would also align neatly with one of the new developmental objectives of Healthy People 2030, which aims to “increase the inclusion of interprofessional prevention education in the curricula of health professions programs” [15]. This initial study demonstrates many common goals shared by medical and pharmacy students; there are likely similar areas of overlap that could be investigated among other health care professions students. These areas are ripe for cooperative efforts and should be organized more formally to improve the nation’s health.

This study was subject to several limitations. The results of this study may not be generalizable to all medical and pharmacy students in Ohio due the response rate and lack of participation from five schools of medicine and two schools of pharmacy citing high survey burden among their students. Additionally, while the explanatory email was designed to minimize potential participant bias, there is no information about non-responders, so any potential systematic differences cannot be assessed. While the HPCTF represents eight health professional education associations, only two disciplines were studied here, given the feasibility of identifying and surveying schools offering these varied degrees across Ohio.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study is significant as it is the first to characterize medical and pharmacy students’ awareness and interest in Healthy People 2030. The results of this study can guide curricular efforts and inform future studies of health professions students. Further research should be conducted to build upon this work and gather data from a larger representative sample of students from all organizational members of the HPCTF to understand their knowledge and interest regarding public health priorities. Additionally, future studies should more fully characterize U.S. health professions students’ perceptions and attitudes regarding public health-related topics in their curricula, as there is scant literature currently [16].

7. Conclusions

Although they reported low familiarity with the Healthy People initiative, both medical and pharmacy students in Ohio recognized core public health topics in their curricula and had an interest in elective courses focused on public health topics. Students from both professions identified similar priorities from Healthy People 2030 to impact in future practice. Students also expressed desire to practice interprofessionally to attain public health goals. Further research should involve a more comprehensive sample of health professions students to gain a clearer understanding of the current state and possible improvements for teaching public health-related topics and initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.B., T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; methodology, R.P.B., W.J.B., T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; formal analysis, T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; investigation, R.P.B. and T.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.B., W.J.B., T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; writing—review and editing, R.P.B., W.J.B., T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; visualization, R.P.B., T.A.D. and N.A.D.M.; project administration, N.A.D.M.; funding acquisition, N.A.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The reviewing body, reference number, and date of exemption approval are as follows: Ohio University Office of Research Compliance, 21-E-37, and 02/22/2021, with Ohio Northern University Institutional Review Board (IRB) acknowledging Ohio University as the IRB of Record. Schools that distributed the survey to their students did not require independent IRB approval or exemption once they received documented verification of ethical approval or exemption from the IRB of Record.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Steven Martin, dean of the Ohio Northern University Raabe College of Pharmacy, for allocation of internal funding to defray the cost of the incentives for participation in the survey. The authors also wish to thank the individuals who facilitated distribution of the survey at their respective institutions including Aleda Chen, Lukas Everly, Joanna Lynn, Sarah Petite, M. Chandra Sekar, and Jessica Wingett, as well as the individuals who assisted in the survey pretesting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The content and discussion provided in this article reflect the findings and opinions of the authors and does not imply endorsement by the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research or the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force.

References

- Tikkanen, R.; Fields, K. The Commonwealth Fund. Multinational Comparisons of Health Systems Data 2020. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/other-publication/2021/feb/multinational-comparisons-health-systems-data-2020 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Collaborative Practice Agreements and Pharmacists’ Patient Care Services: A Resource for Pharmacists. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/translational_tools_pharmacists.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Choe, H.M.; Standiford, C.J.; Brown, M.T. Embedding Pharmacists into the Practice. American Medical Association STEPS Forward. Available online: www.stepsforward.org/modules/embedded-pharmacists (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Gebhart, F. Provider and Payment Status: An Update. Drug Top. 2019, 163, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart, F. More Pharmacists Move into Medical Practices, More Doctors See Value. Drug Top. 2018, 162, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Prevention Teaching and Research. APTR Healthy People Curriculum Task Force. Available online: https://www.aptrweb.org/page/HPC_Taskforce (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Association for Prevention Teaching and Research. Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework. Available online: https://www.teachpopulationhealth.org (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Medicaid and Public Health Partnership Learning Series. Public Health and Population Health 101. Available online: https://www.astho.org/Health-Systems-Transformation/Medicaid-and-Public-Health-Partnerships/Learning-Series/Public-Health-and-Population-Health-101/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020: Educational and Community-Based Programs. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/educational-and-community-based-programs/objectives (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Borgialli, D.A.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Healthy People 2010 Emergency Medicine Module: A Multicenter Survey and Educational Intervention. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 130, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.N. Pharmacists’ Knowledge of Social Determinants of Health in Post-Graduate Pharmacy Residency Programs; Wright State University: Dayton, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Schools. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/schools (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Mehling, K.; Jeong, S.J. Perceptions of Public Health: The Challenges of Public Health Education Integration. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 2, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).