Impact of Propofol Sedation upon Caloric Overfeeding and Protein Inadequacy in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Nutrition Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Complications Associated with Hypertriglyceridemia and Caloric Overfeeding

4.2. The Rationale and Dilemma for Providing Sufficient Protein Intake

4.3. Strategies to Avoid Overfeeding with Calories and to Maintain or Improve Protein Intake

4.3.1. Parenteral Nutrition

4.3.2. Enteral Nutrition

4.4. Case Studies

4.4.1. Case Study 1 (PN)

4.4.2. Case Study 2 (EN)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carney, N.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Hawryluk, G.W.; Bell, M.J.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.T.; Dickerson, R.N. Propofol: A risk factor for caloric overfeeding and inadequate protein delivery. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 55, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arruda, A.P.; Martins, L.; Lima, S. Influence of propofol sedation in the benefits of EPA+GLA nutrition for the treatment of severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, A483. [Google Scholar]

- Asa’ari, A.M.; Passey, S.T.; Mendis, M.; Carr, B. What proportion of calories given to critically ill patients come from propofol? Inten. Care Med. Exper. 2015, 3, A188. [Google Scholar]

- Bousie, E.; van Blokland, D.; Lammers, H.J.; van Zanten, A.R. Relevance of non-nutritional calories in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buckley, C.T.; Van Matre, E.T.; Fischer, P.E.; Minard, G.; Dickerson, R.N. Improvement in protein delivery for critically ill patients requiring high-dose propofol therapy and enteral nutrition. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2021, 36, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Nogueira, P.B.; Ribeiro, F.A.; Bottairi, D.S.; Piovacari, S.F.; Assis, T.; Laselva, C.R.; Toledo, D.O. Relevance of non-nutritional calories by propofol in Covid-19 critically ill patients. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 40, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charriere, M.; Ridley, E.; Hastings, J.; Bianchet, O.; Scheinkestel, C.; Berger, M.M. Propofol sedation substantially increases the caloric and lipid intake in critically ill patients. Nutrition 2017, 42, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChicco, R.; Materese, L.; Hummell, A.C.; Speerhas, R.; Seidner, D.; Steiger, E. Contribution of calories from propofol to total energy intake. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1995, 95, A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, S.; Herkes, R.; Forrest, P. Nutrition support during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in adults: A retrospective audit of 86 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, J.; Ridley, E.J.; Bianchet, O.; Roodenburg, O.; Levkovich, B.; Scheinkestel, C.; Pilcher, D.; Udy, A. Does propofol sedation contribute to overall energy provision in mechanically ventilated critically ill adults? A retrospective observational study. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2018, 42, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Pastrana, E.; Serralde-Zuniga, A.; Calderon de la Barca, A.M. Critical energy and protein deficits with high contribution of non-nutrient calories after one week into an intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 40, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.S.; O’Connor, S.N.; Lange, K.; Rivett, J.; Chapman, M.J. Enteral nutrition for patients in septic shock: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care Resuscit 2010, 12, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M.; Saunders, J.; Quinn, C.; Halloran, T.O.; Riain, S.O. Improvements in goal protein achieved following a change from propofol 1% to propofol 2% and a change in enteral feeding protocol in the ICU. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bowles, J.; Jewkes, C. Propofol use precludes prescription of estimated nitrogen requirements. J. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 20, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, E.; Remmington, C. Observational study evaluating the nutritional impact of changing from 1% to 2% propofol in a cardiothoracic adult critical care unit. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 34, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.J.; Hall, R.I.; Kramer, A.H.; Robertson, H.L.; Gallagher, C.N.; Zygun, D.A. Sedation for critically ill adults with severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrey, T.S.; Dunlap, A.W.; Brown, R.O.; Dickerson, R.N.; Kudsk, K.A. Pharmacologic influence on nutrition support therapy: Use of propofol in a patient receiving combined enteral and parenteral nutrition support. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 1996, 11, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajcova, A.; Waldauf, P.; Andel, M.; Duska, F. Propofol infusion syndrome: A structured review of experimental studies and 153 published case reports. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Llop, J.; Sabin, P.; Garau, M.; Burgos, R.; Perez, M.; Masso, J.; Cardona, D.; Sanchez Segura, J.M.; Garriga, R.; Redondo, S.; et al. The importance of clinical factors in parenteral nutrition-associated hypertriglyceridemia. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.M.; Park, Y.; Harris, W.S. Lipoprotein liapse and triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2001, 16, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClave, S.A.; Taylor, B.E.; Martindale, R.G.; Warren, M.M.; Johnson, D.R.; Braunschweig, C.; McCarthy, M.S.; Davanos, E.; Rice, T.W.; Cresci, G.A.; et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2016, 40, 159–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidner, D.L.; Mascioli, E.A.; Istfan, N.W.; Porter, K.A.; Selleck, K.; Blackburn, G.L.; Bistrian, B.R. Effects of long-chain triglyceride emulsions on reticuloendothelial system function in humans. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 1989, 13, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpers, S.S.; Romberger, D.J.; Bunce, S.B.; Pingleton, S.K. Nutritionally associated increased carbon dioxide production. Excess total calories vs high proportion of carbohydrate calories. Chest 1992, 102, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosmarin, D.K.; Wardlaw, G.M.; Mirtallo, J. Hyperglycemia associated with high, continuous infusion rates of total parenteral nutrition dextrose. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 1996, 11, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusman, O.; Theilla, M.; Cohen, J.; Kagan, I.; Bendavid, I.; Singer, P. Resting energy expenditure, calorie and protein consumption in critically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allingstrup, M.J.; Esmailzadeh, N.; Wilkens Knudsen, A.; Espersen, K.; Hartvig Jensen, T.; Wiis, J.; Perner, A.; Kondrup, J. Provision of protein and energy in relation to measured requirements in intensive care patients. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, D.D.; Fuentes, E.; Quraishi, S.A.; Lee, J.; Kaafarani, H.M.A.; Fagenholz, P.; Butler, K.; DeMoya, M.; Chang, Y.; Velmahos, G. Early protein inadequacy is associated with longer intensive care unit stay and fewer ventilator-free days: A retrospective analysis of patients with prolonged surgical intensive care unit stay. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2018, 42, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, M.; Heyland, D.K.; Chittams, J.; Sammarco, T.; Compher, C. Clinical outcomes related to protein delivery in a critically ill population: A multicenter, multinational observation study. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2016, 40, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.M.; Soguel, L.; Charriere, M.; Theriault, B.; Pralong, F.; Schaller, M.D. Impact of the reduction of the recommended energy target in the ICU on protein delivery and clinical outcomes. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choban, P.; Dickerson, R.; Malone, A.; Worthington, P.; Compher, C. American Society for, Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, ASPEN Clinical guidelines: Nutrition support of hospitalized adult patients with obesity. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 714–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choban, P.S.; Dickerson, R.N. Morbid obesity and nutrition support: Is bigger different? Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2005, 20, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Pitts, S.L.; Maish, G.O., 3rd; Schroeppel, T.J.; Magnotti, L.J.; Croce, M.A.; Minard, G.; Brown, R.O. A reappraisal of nitrogen requirements for patients with critical illness and trauma. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheinkestel, C.D.; Kar, L.; Marshall, K.; Bailey, M.; Davies, A.; Nyulasi, I.; Tuxen, D.V. Prospective randomized trial to assess caloric and protein needs of critically Ill, anuric, ventilated patients requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Nutrition 2003, 19, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Medling, T.L.; Smith, A.C.; Maish, G.O., 3rd; Croce, M.A.; Minard, G.; Brown, R.O. Hypocaloric, high-protein nutrition therapy in older vs younger critically ill patients with obesity. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Maish, G.O., 3rd; Croce, M.A.; Minard, G.; Brown, R.O. Influence of aging on nitrogen accretion during critical illness. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2015, 39, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnelli, N.; Gibbs, L.; Larrivee, J.; Sahu, K.K. Challenges of maintaining optimal nutrition dtatus in COVID-19 patients in intensive care settings. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.M.; Dickerson, R.N.; Alexander, K.H.; Brown, R.O.; Minard, G. Factors causing interrupted delivery of enteral nutrition in trauma intensive care unit patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2004, 19, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Mitchell, J.N.; Morgan, L.M.; Maish, G.O., 3rd; Croce, M.A.; Minard, G.; Brown, R.O. Disparate response to metoclopramide therapy for gastric feeding intolerance in trauma patients with and without traumatic brain injury. JPEN J. Parenter Enter. Nutr. 2009, 33, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessler, C.N.; Gosnell, M.S.; Grap, M.J.; Brophy, G.M.; O’Neal, P.V.; Keane, K.A.; Tesoro, E.P.; Elswick, R.K. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: Validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.F.; Wolfe, R.R.; Mullany, C.J.; Mathews, D.E.; Bier, D.M. Glucose requirements following burn injury. Parameters of optimal glucose infusion and possible hepatic and respiratory abnormalities following excessive glucose intake. Ann. Surg. 1979, 190, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn, D.H. Nutritional requirements of adult surgical patients. Crit. Care Med. 1980, 8, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Rosato, E.F.; Mullen, J.L. Net protein anabolism with hypocaloric parenteral nutrition in obese stressed patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 44, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilmore, D.W.; Aulick, L.H.; Mason, A.D.; Pruitt, B.A., Jr. Influence of the burn wound on local and systemic responses to injury. Ann. Surg. 1977, 186, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudsk, K.A.; Minard, G.; Croce, M.A.; Brown, R.O.; Lowrey, T.S.; Pritchard, F.E.; Dickerson, R.N.; Fabian, T.C. A randomized trial of isonitrogenous enteral diets after severe trauma. An immune-enhancing diet reduces septic complications. Ann. Surg. 1996, 224, 531–540, discussion 540-533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Harris, S.L. Difficulty in administration of liquid protein solution via an enteral feeding tube. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, 796–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, R.N.; Boschert, K.J.; Kudsk, K.A.; Brown, R.O. Hypocaloric enteral tube feeding in critically ill obese patients. Nutrition 2002, 18, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Patient Population | N | Nutrition Route | Calories from Nutrition, (kcals/d) | Calories from Propofol (kcals/d) | Total Calories (kcals/d) | % of Calories from Propofol | Duration of Propofol, Days | Protein Intake (g/kg/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arruda, 2009 | ICU ALI, ARDS | 30 | EN | - | 356 | - | - | - | - |

| Asa’ari, 2015 * | ICU | 50 | EN and PN | ~1170 | ~130 | ~1300 | 10% | - | - |

| Bousie, 2016 | ICU | 101 | EN and PN | ~1400 | 230 (IQR 85–595) | ~1600 kcals/d | 14% | - | - |

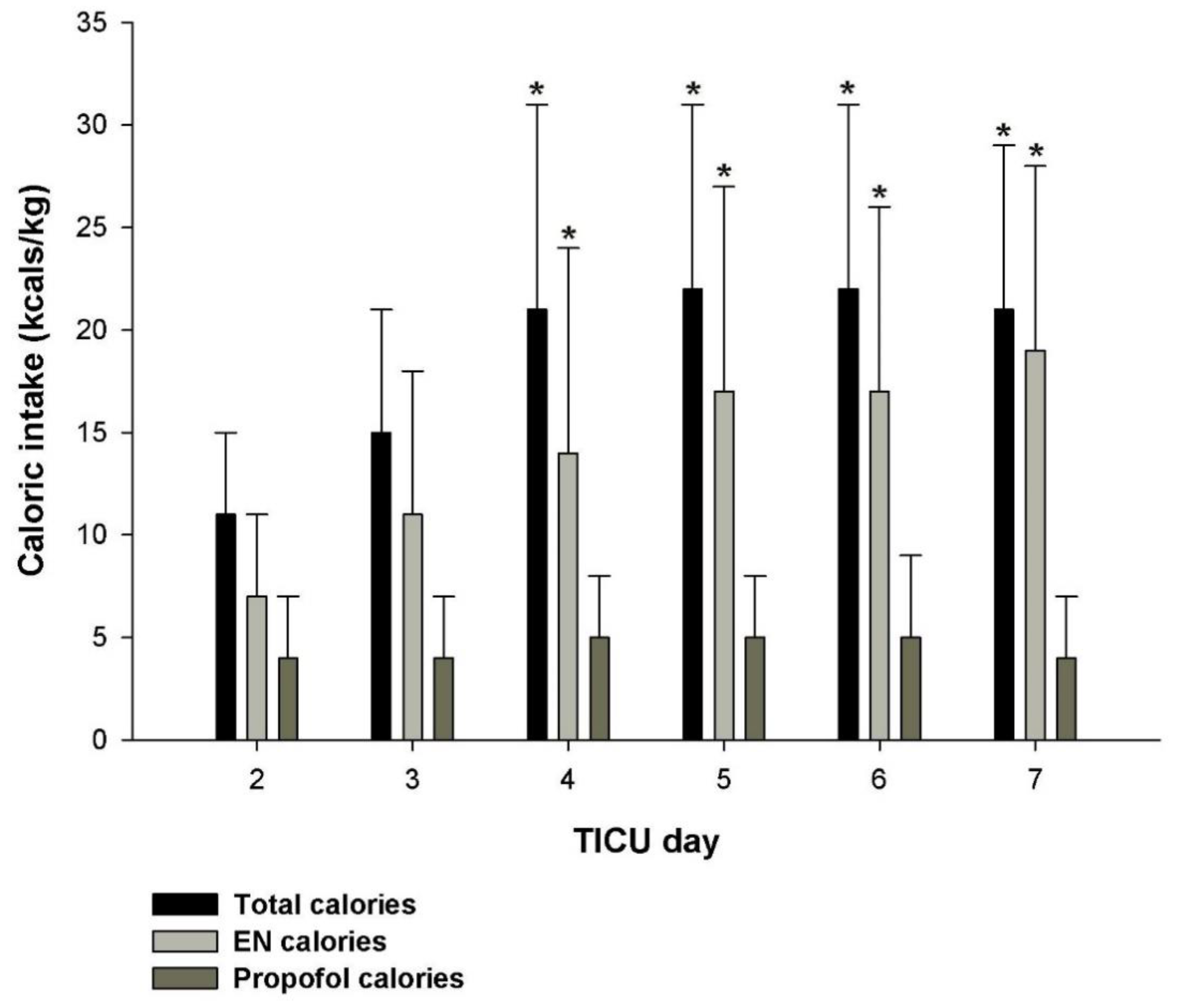

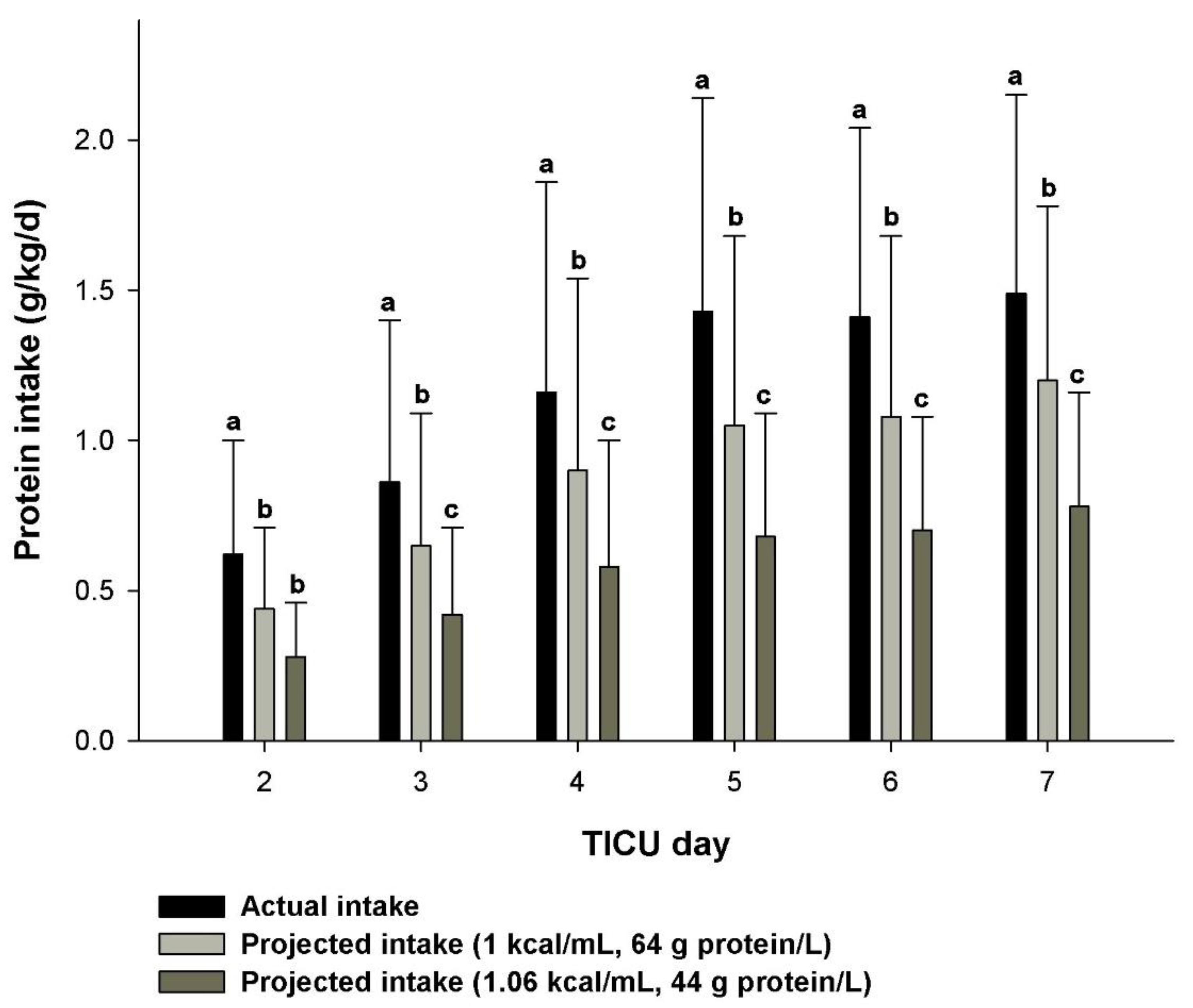

| Buckley, 2021 | Traumatic brain injury | 51 | EN | 16 ± 9 Kcal/kg/d | 356 ± 243 5 ± 3 Kcal/kg/d | 22 ± 9 Kcal/kg/d | 24% | 6 ± 4 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| Castro, 2020 * | COVID-19 | 39 | EN | ~1473 | 260 | 1733 | 15 ± 8% | 8 ± 6 | 88% of goal |

| Charriere, 2017 | ICU 1% or 2% propofol | 687 | EN | ~1216 | 146 ± 117 | 1362 ± 811 | 17 ± 21% (first few days) | - | - |

| DeChicco, 1995 * | ICU | 19 | EN and PN | ~1350 | 215 (range 79–535) | - | 15% of BEE | - | - |

| Ferrie, 2013 | Cardiac failure and ECMO | 86 | EN and PN | ~1464 | 130 ± 184 | 1594 ± 628 | 8% | 9 ± 4 | 58 ± 29 g/d |

| Hastings, 2018 | ICU | 325 | EN and PN | ~1231 | 119 (IQR 50–730) | ~1350 | 8–10% | - | <1.2 for most pts |

| Ibarra, 2020 * | Trauma, Neurologic | 26 | EN | 10 | 2 kcal/kg/d | 12 | 18% | - | 0.4 |

| Rai, 2010 | ICU Sepsis | 43 | EN | ~1400 | 79 (range, 0–426) | ~1500 | 5% | - | - |

| Richardson, 2018 * | ICU 1% propofol 2% propofol | 79 75 | EN EN | 1031 1244 | 111 60 | 1142 1304 | 10% 5% | - - | 61% (goal) 70% (goal) |

| Taylor, 2005 | Trauma, Neurosurgical | 85 | EN | - | - | Goal: BEE X stress factors | 19% | - | <90% goal for 51% of pts; <80% of goal for 21% of pts |

| Terblanche, 2020 | CT-ICU 1% propofol 2% propofol | 50 50 | EN EN | 13 ± 6 Kcal/kg/d 16 ± 5 Kcal/kg/d | 353 (IQR 224 to 447) 185 (IQR 118 to 244) | 16 ± 5 Kcal/kg/d 18 ± 7 Kcal/kg/d | 14% 10% | - - | 0.8 ± 0.4 0.9 ± 0.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dickerson, R.N.; Buckley, C.T. Impact of Propofol Sedation upon Caloric Overfeeding and Protein Inadequacy in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Nutrition Support. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9030121

Dickerson RN, Buckley CT. Impact of Propofol Sedation upon Caloric Overfeeding and Protein Inadequacy in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Nutrition Support. Pharmacy. 2021; 9(3):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9030121

Chicago/Turabian StyleDickerson, Roland N., and Christopher T. Buckley. 2021. "Impact of Propofol Sedation upon Caloric Overfeeding and Protein Inadequacy in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Nutrition Support" Pharmacy 9, no. 3: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9030121

APA StyleDickerson, R. N., & Buckley, C. T. (2021). Impact of Propofol Sedation upon Caloric Overfeeding and Protein Inadequacy in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Nutrition Support. Pharmacy, 9(3), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9030121