COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

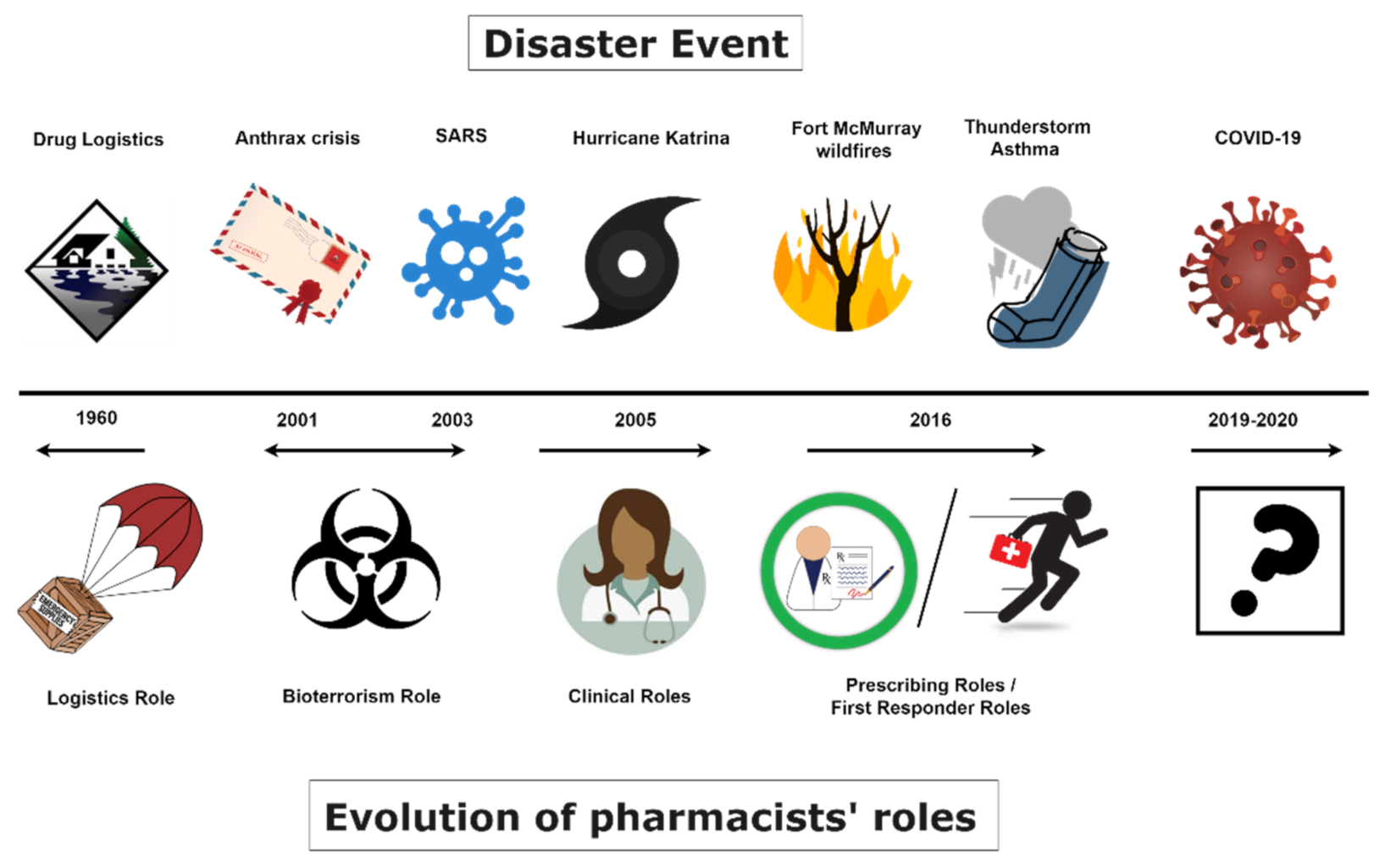

1. Introduction

1.1. What Does a Pharmacist See Reflected in a Mirror?

1.2. Will the COVID-19 Pandemic Follow This Trend and Be the Catalyst for Further Change?

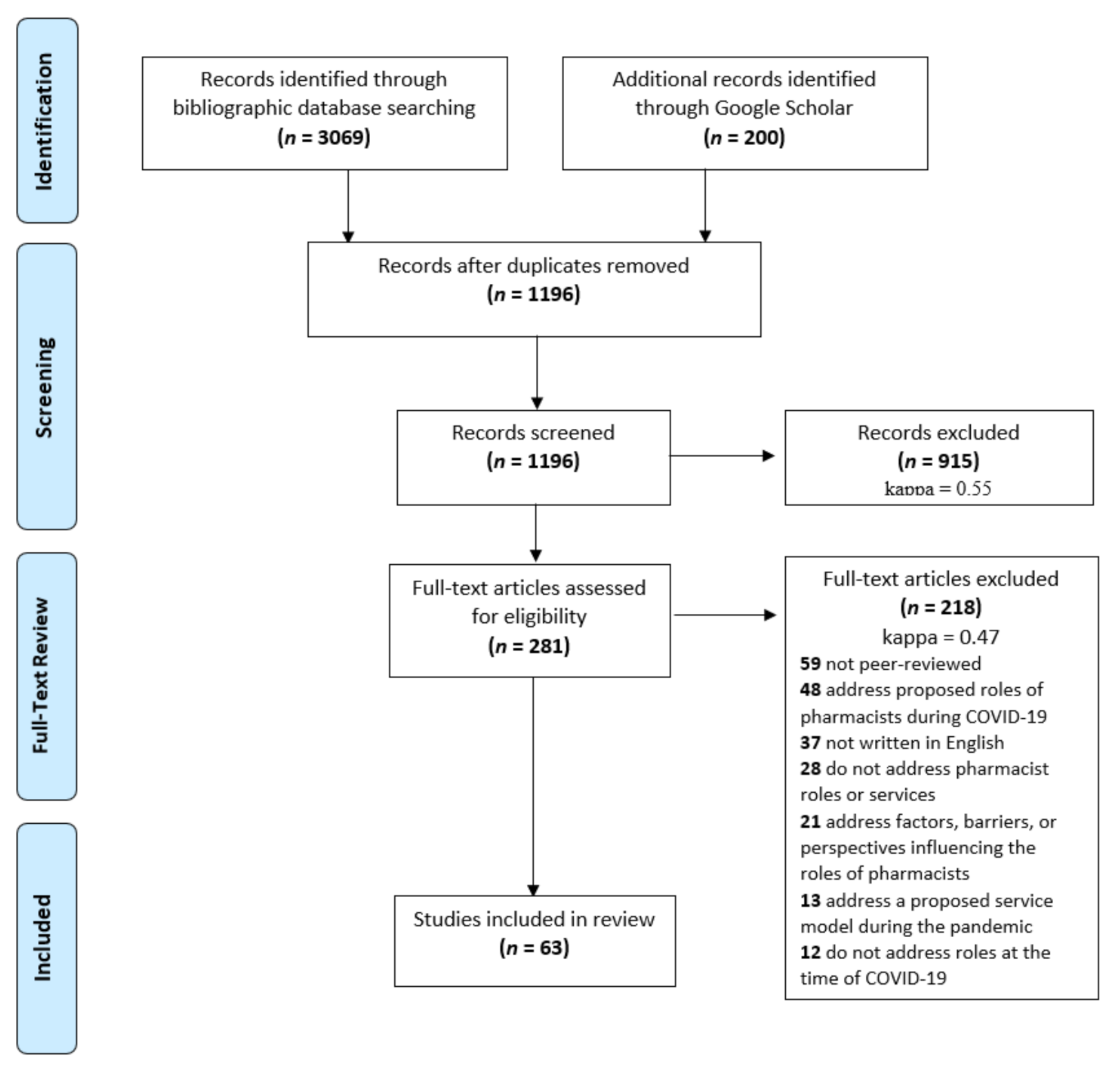

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Charactertistics

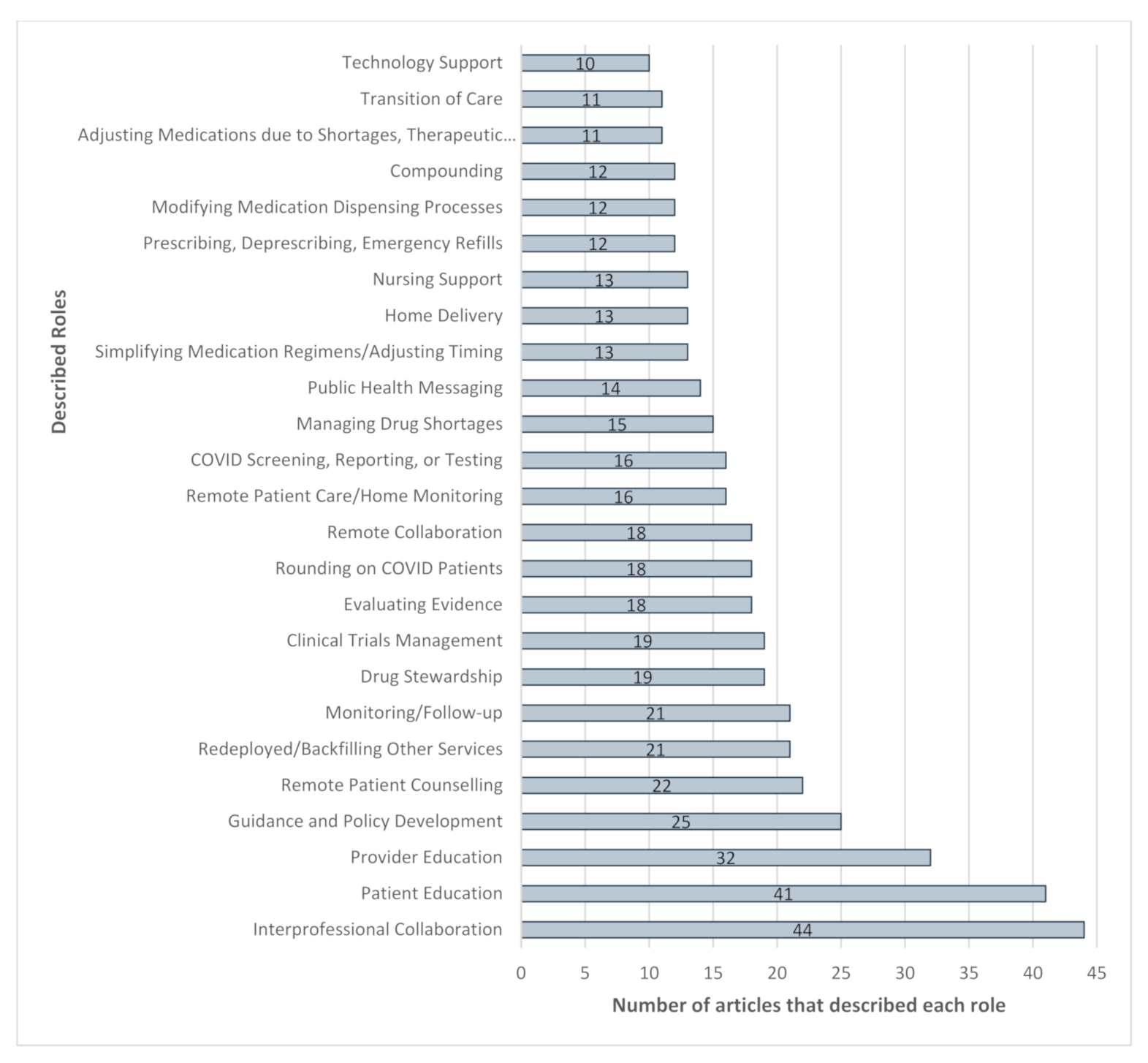

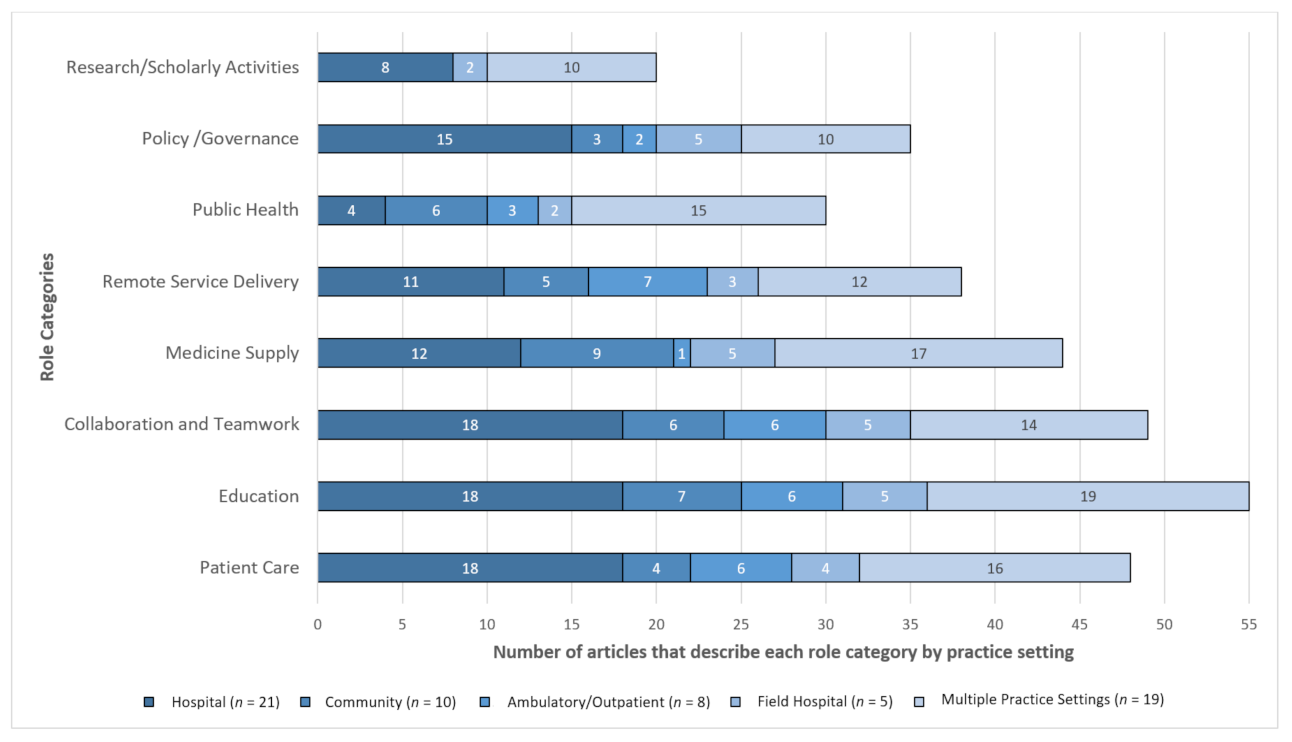

3.2. Overall Roles and Services

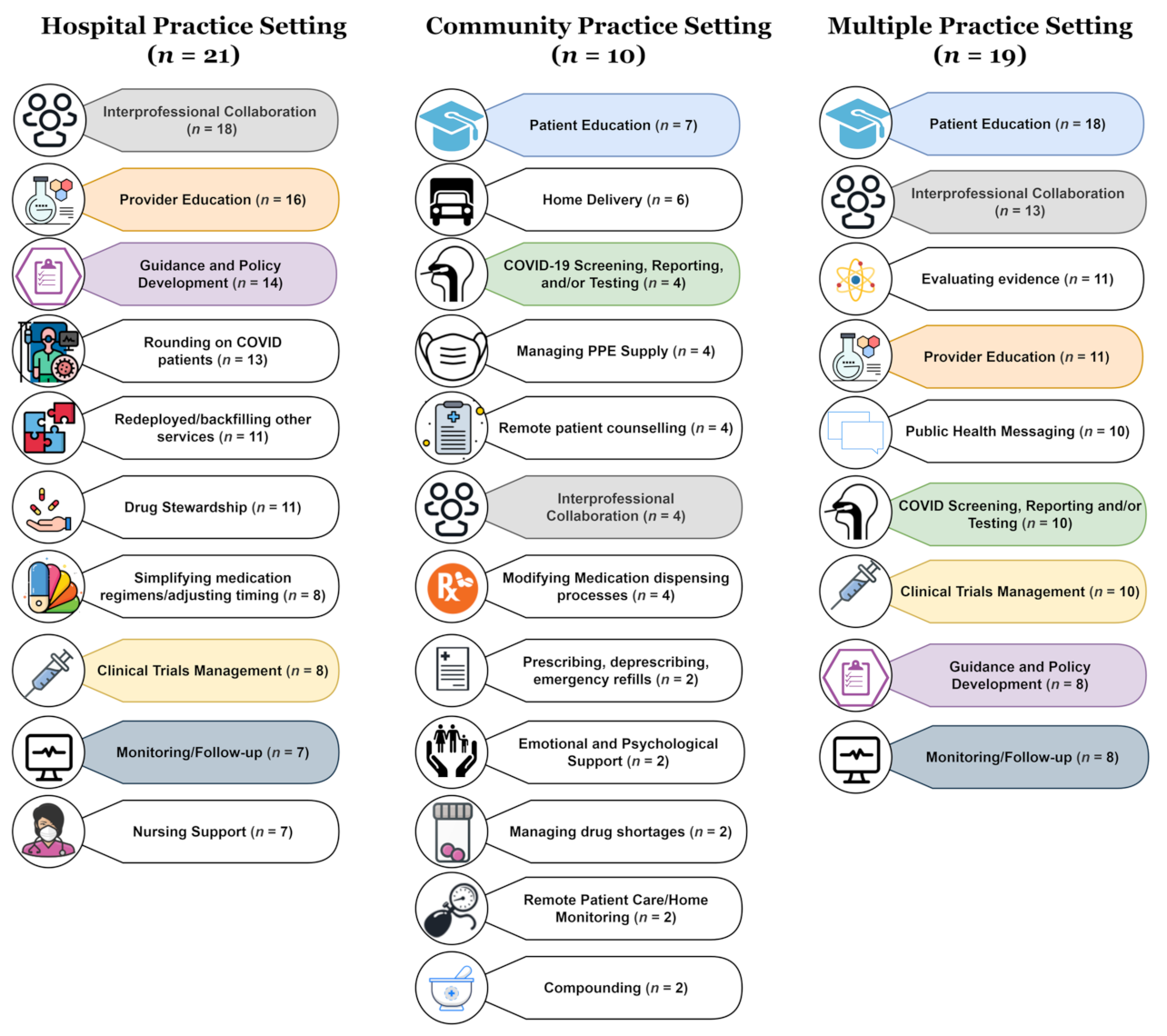

3.3. Practice Setting

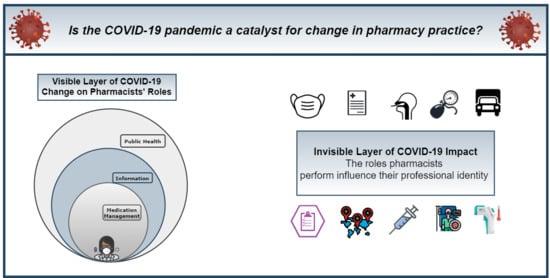

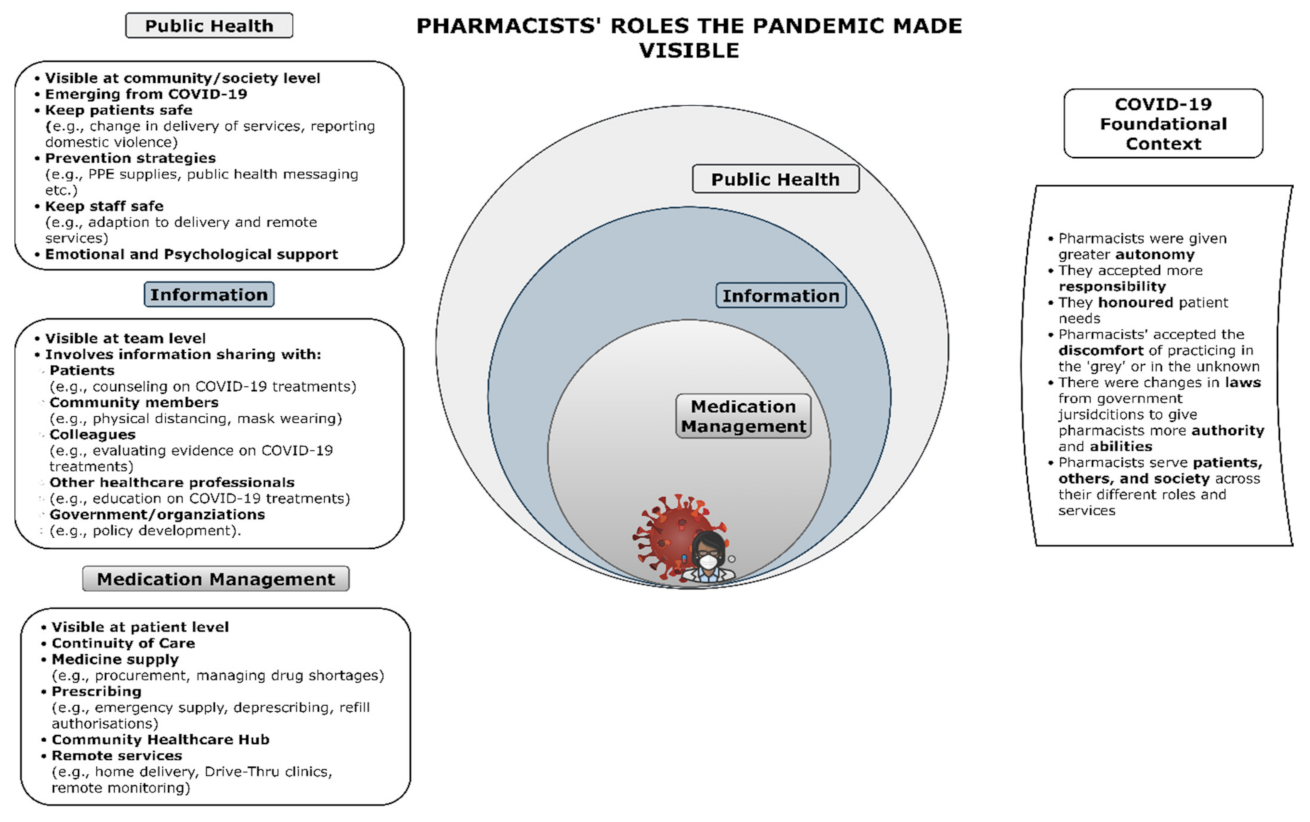

3.4. Conceptual Framework Model

3.4.1. Medication Management Sphere

3.4.2. Information Sphere

3.4.3. Public Health Sphere

3.4.4. COVID-19 Foundational Context

4. Discussion

4.1. What Are Pharmacists’ Roles and Services during COVID-19?

4.2. What Are the Public Implications of These Roles?

4.3. What Do Pharmacists See in the Mirror?

4.4. What Does It Mean for the Future of the Pharmacy Profession?

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Is the COVID-19 Pandemic a Catalyst for Change in Pharmacy Practice?

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodrick, E.; Reay, T. Constellations of institutional logics: Changes in the professional work of pharmacists. Work Occup. 2011, 38, 372–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.E.; Singleton, J.A.; Tippett, V.; Nissen, L.M. Defining pharmacists’ roles in disasters: A Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0227132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.E.; Tippett, V.; Singleton, J.A.; Nissen, L.M. Disaster health management: Do pharmacists fit in the team? Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.E.; Van Haaften, D.; Horon, K.; Tsuyuki, R.T. The evolution of pharmacists’ roles in disasters, from logistics to assessing and prescribing. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott.) 2020, 153, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.C.; Parkin, R. The challenges of COVID-19 for community pharmacists and opportunities for the future. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Mansour, M.; Bonsignore, A.; Ciliberti, R. The role of hospital and community pharmacists in the management of COVID-19: Towards an expanded definition of the roles, responsibilities, and duties of the pharmacist. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.E. The Roles of Pharmacists in Disaster Health Management in Natural and Anthropogenic Disasters. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, T.; Merchan, C.; Arnouk, S.; Cirrone, F.; Dabestani, A.; Papadopoulos, J. COVID-19 pandemic preparedness: A practical guide from clinical pharmacists’ perspective. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1510–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, S.; Thalapparambath, R.; Al Ghamdi, F.H. COVID-19 pandemic: Response plan by the Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare inpatient pharmacy department. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2009–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, L.H.; Cooper, M.K.; Wiggins, E.H.; Miller, K.M.; Murray, E.; Harris, S.; Kramer, J.S. Utilizing pharmacists to optimize medication management dtrategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, D.A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Cairns, K.A.; Eljaaly, K.; Gauthier, T.P.; Langford, B.J.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Messina, A.P.; Michael, U.C.; Saad, T.; et al. Global contributions of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguy, J.; Hitchen, S.A.; Hort, A.L.; Huynh, C.; Rawlins, M.D.M. The role of a Coronavirus disease 2019 pharmacist: An Australian perspective. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visacri, M.B.; Figueiredo, I.V.; de Lima, T.M. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merks, P.; Jakubowska, M.; Drelich, E.; Świeczkowski, D.; Bogusz, J.; Bilmin, K.; Sola, K.F.; May, A.; Majchrowska, A.; Koziol, M.; et al. The legal extension of the role of pharmacists in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Qiu, F.; Sun, S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, G.R.; Zhao, R.S. Mapping evidence of pharmacy services for COVID-19 in China. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 555753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Luo, P.; Tang, M.; Hu, Q.; Polidoro, J.P.; Sun, S.; Gong, Z. Providing pharmacy services during the coronavirus pandemic. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburas, W.; Alshammari, T.M. Pharmacists’ roles in emergency and disasters: COVID-19 as an example. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 1797–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, I.; Eltahir, A.; Fernyhough, L.; El-Bardissy, A.; Ahmed, R.; Abdulgelil, M.; Elgaily, D.; Mohammed, A.; Jassim, A.; Barakat, L.; et al. The experience of Hamad General Hospital collaborative anticoagulation clinic in Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves da Costa, F.; Lee, V.; Leite, S.N.; Murillo, M.D.; Menge, T.; Antoniou, S. Pharmacists reinventing their roles to effectively respond to COVID-19: A global report from the international pharmacists for anticoagulation care taskforce (iPACT). J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, M.W.L. ‘To be or not to be in the ward’: The impact of Covid-19 on the role of hospital-based clinical pharmacists—A qualitative study. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.D.; West, N.; Sudekum, D.M.; Hecht, J.P. Perspectives from the frontline: A pharmacy department’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Como, M.; Carter, C.W.; Larose-Pierre, M.; O’Dare, K.; Hall, C.R.; Mobley, J.; Robertson, G.; Leonard, J.; Tew, L. Pharmacist-led chronic care management for medically underserved rural populations in Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2020, 17, E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRemer, C.E.; Reiter, J.; Olson, J. Transitioning ambulatory care pharmacy services to telemedicine while maintaining multidisciplinary collaborations. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Val, J.; Sohal, G.; Sarwar, A.; Ahmed, H.; Singh, I.; Coleman, J.J. Investigating the challenges and opportunities for medicines management in an NHS field hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 28, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzierba, A.L.; Pedone, T.; Patel, M.K.; Ciolek, A.; Mehta, M.; Berger, K.; Ramos, L.G.; Patel, V.D.; Littlefield, A.; Chuich, T.; et al. Rethinking the drug distribution and medication management model: How a New York City hospital pharmacy department responded to COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeddini, A.; Botross, A.; Gerochi, R.; Gazarin, M.; Elshahawi, A. Pharmacy response to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from Canada. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeddini, A.; Prabaharan, T.; Almasalkhi, S.; Tran, C. Pharmacists and COVID-19. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N.C.; Quinn, N.J.; Khalique, S.; Sinnett, M.; Eisen, L.; Goriacko, P. Clinical pharmacists: An invaluable part of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 frontline response. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gil, M.; Velayos-Amo, C. Hospital pharmacist experience in the intensive care unit: Plan COVID. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Gu, M.; Zeng, F.; Hu, H.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, C. Pharmacy administration and pharmaceutical care practice in a module hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, 431–438.e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Ambreen, G.; Muzammil, M.; Raza, S.S.; Ali, U. Pharmacy services during COVID-19 pandemic: Experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital in Pakistan. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, O.M.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Al Mazrouei, N. Role of telepharmacy in pharmacist counselling to coronavirus disease 2019 patients and medication dispensing errors. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahun, G.G.; Kahsay, G.M.; Asayehegn, A.T.; Demoz, G.T.; Desta, D.M.; Gebretekle, G.B. Pharmacy preparedness and response for the prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Aksum, Ethiopia; a qualitative exploration. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, E.S.; Philbert, D.; Bouvy, M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the provision of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2002–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemtiri, J.; Matusik, E.; Cousein, E.; Lambiotte, F.; Elbeki, N. The role of the critical care pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2020, 78, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zheng, S.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Zhao, R. Fighting against COVID-19: Innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Razaki, H.; Mui, V.; Rao, P.; Brocavich, S. The pivotal role of pharmacists during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, e73–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Ma, C.; Lau, A.H.; Zhong, M. Role of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic in China-Shanghai Experiences. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, R.H.M.; Shalhoub, R.; Sridharan, B.K. The experiences of the community pharmacy team in supporting people with dementia and family carers with medication management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Lin, Y.W.; Wang, J.Y.; Lin, M.H. The pharmaceutical practice of mask distribution by pharmacists in Taiwan’s community pharmacies under the Mask Real-Name System, in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2020, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margusino-Framinan, L.; Illarro-Uranga, A.; Lorenzo-Lorenzo, K.; Monte-Boquet, E.; Marquez-Saavedra, E.; Fernandez-Bargiela, N.; Gomez-Gomez, D.; Lago-Rivero, N.; Poveda-Andres, J.L.; Diaz-Acedo, R.; et al. Pharmaceutical care to hospital outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telepharmacy. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConachie, S.; Martirosov, D.; Wang, B.; Desai, N.; Jarjosa, S.; Hsaiky, L. Surviving the surge: Evaluation of early impact of COVID-19 on inpatient pharmacy services at a community teaching hospital. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchan, C.; Soliman, J.; Ahuja, T.; Arnouk, S.; Keeley, K.; Tracy, J.; Guerra, G.; DaCosta, K.; Papadopoulos, J.; Dabestani, A. COVID-19 pandemic preparedness: A practical guide from an operational pharmacy perspective. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. COVID-19 disaster response: A pharmacist volunteer’s experience at the epicenter. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1786–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreiras Martins, M.A.; Fonseca de Medeiros, A.; Dias Carneiro de Almeida, C.; Moreira Reis, A.M. Preparedness of pharmacists to respond to the emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: A comprehensive overview. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, V.; Cadogan, C.; Fialova, D.; Henman, M.C.; Hazen, A.; Okuyan, B.; Lutters, M.; Stewart, D. Provision of clinical pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of pharmacists from 16 European countries. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Marti, J.F.; Bravo-Jose, P.; Saez-Lleo, C.; Fernandez-Villalba, E. Specialized pharmaceutical care in social health centers in the times of COVID-19. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, D.S.; Fulman, M.; Champagne, J.; Awad, N. COVID-19 pandemic planning, response, and lessons learned at a community hospital. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, K.; Xiong, Y.; Song, W.; Zhou, B. Wuchang Fangcang Shelter Hospital: Practices, experiences, and lessons learned in controlling COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surapat, B.; Sungkanuparph, S.; Kirdlarp, S.; Lekpittaya, N.; Chunnguleum, K. Role of clinical pharmacists in telemonitoring for patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, L.; Whitfield, K.; Nickerson-Troy, J.; Francoforte, K. Drive-thru anticoagulation clinic: Can we supersize your care today? J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, e65–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, N.; Gust, C.; Porter, E.; Gilchrist, N.; Amaral, A. Implementation of field hospital pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Heal. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Qian, Y.; Kun, Z. Drugs supply and pharmaceutical care management practices at a designated hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1978–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, A.D.; Patel, P.C.; Sullivan, M.; Potts, A.; Knostman, M.; Humphreys, E.; O’Neal, M.; Bryant, A.; Torr, D.K.; Lobo, B.; et al. From natural disaster to pandemic: A health-system pharmacy rises to the challenge. Am. J. Heal. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1986–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Alrabiah, Z.; Alhossan, A. Saudi Arabia, pharmacists and COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Farraye, F.A.; Moss, A.C. Impact of clinical pharmacists in inflammatory bowel disease centers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1532–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzik, K.A.; Bethishou, L. The impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy transitions of care services. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1908–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, O.M.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Abdel-Qader, D.H.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Al Mazrouei, N. Evaluation of Telepharmacy Services in Light of COVID-19. Telemed. e-Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristina, S.A.; Herliana, N.; Hanifah, S. The perception of role and responsibilities during covid-19 pandemic: A survey from indonesian pharmacists. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 3034–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, I.; Berlie, H.D.; Lipari, M.; Martirosov, A.L.; Duong, A.A.; Faraj, M.; Bacon, O.; Garwood, C.L. Ambulatory care practice in the COVID-19 era: Redesigning clinical services and experiential learning. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukattash, T.L.; Jarab, A.S.; Mukattash, I.; Nusair, M.B.; Farha, R.A.; Bisharat, M.; Basheti, I.A. Pharmacists’ perception of their role during COVID-19: A qualitative content analysis of posts on Facebook pharmacy groups in Jordan. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.T.; Yang, Y.H.K. Community pharmacists in Taiwan at the frontline against the novel Coronavirus pandemic: Gatekeepers for the rationing of personal protective equipment. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez Bejarano, A.; Villar Santos, P.; de Robustillo-Cortes, M.L.A.; Sanchez Gomez, E.; Santos Rubio, M.D. Implementation of a novel home delivery service during pandemic. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, C.O.L. Community pharmacist in public health emergencies: Quick to action against the coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erstad, B.L. Caring for the COVID patient: A clinical pharmacist’s perspective. Ann. Pharmacother. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Malik, I. COVID-19 and community pharmacy services in Pakistan: Challenges, barriers and solution for progress. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Jupp, J.; Chazan, G.; O’Connor, S.; Chan, A. Global oncology pharmacy response to COVID-19 pandemic: Medication access and safety. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 26, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, E.M.; Alwan, L.; Pitney, C.; Taketa, C.; Indorf, A.; Held, L.; Lee, K.S.; Son, M.; Chi, M.; Diamantides, E.; et al. Establishing clinical pharmacist telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D.; Guiu-Segura, J.M.; Sousa-Pinto, G.; Wang, L.N. How COVID-19 has impacted the role of pharmacists around the world. Farm. Hosp. 2021, 45, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.F.; Samanta, S.; Mustafa, F. Is the paradigm of community pharmacy practice expected to shift due to COVID-19? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2046–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.E. An Unassuming Pair: Pharmacists and Disasters. Available online: https://apfmag.mdmpublishing.com/an-unassuming-pair-pharmacists-and-disasters/ (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Watson, K.E. Hazard Note 78: On the Frontline: The Roles of Pharmacists in Disasters; Bushfire and Natural Hazard CRC: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, B.; Carroll, B. Re-viewing ‘role’ in processes of identity construction. Organization 2008, 15, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chreim, S.; Williams, B.E.; Hinings, C.R. Interlevel influences on the reconstruction of professional role identity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1515–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Goodrick, E.; Casebeer, A.; Hinings, C.R. Legitimizing new practices in primary health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. Provisional Selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 764–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Haydt, S.; Farrell, B.; Kennie, N.; Sellors, C.; Martin, C.; Dolovich, L. Pharmacist’s identity development within multidisciplinary primary health care teams in Ontario; qualitative results from the IMPACT project. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2009, 5, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Goodrick, E.; Waldorff, S.B.; Casebeer, A. Getting leopards to change their spots: Co-creating a new professional role identity. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1043–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotho, S. Professional identity–product of structure, product of choice: Linking changing professional identity and changing professions. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2008, 21, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Greenwood, R.; Hinings, C. Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2002, 45, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| Practice Setting | % (n = 63) | Country | % (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory Care and Outpatient Clinics | 12.7% (8) | Australia | 1.6% (1) |

| Community | 15.9% (10) | Brazil | 1.6% (1) |

| Field Hospital | 7.9% (5) | Canada | 3.2% (2) |

| Hospital | 33.3% (21) | China | 14.3% (9) |

| Multiple practice settings | 30.2% (19) | Ethiopia | 1.6% (1) |

| Methods Described | % (n = 63) | France | 1.6% (1) |

| Commentary | 74.6% (47) | Indonesian | 1.6% (1) |

| Literature Review | 7.9% (5) | Jordan | 1.6% (1) |

| Qualitative—Interview | 6.3% (4) | Malaysia | 1.6% (1) |

| Quantitative—Content Analysis | 1.6% (1) | Netherlands | 1.6% (1) |

| Quantitative—Observational Study | 4.8% (3) | Pakistan | 3.2% (2) |

| Quantitative—Survey | 4.8% (3) | Saudi Arabia | 4.8% (3) |

| Published Online Month 2020 | % (n = 63) | Spain | 6.3% (4) |

| February | 1.6% (1) | Taiwan | 3.2% (2) |

| March | 1.6% (1) | Thailand | 1.6% (1) |

| April | 7.9% (5) | United Arab Emirates | 3.2% (2) |

| May | 12.7% (8) | United Kingdom | 3.2% (2) |

| June | 19% (12) | US | 31.5% (20) |

| July | 14.3% (9) | Multiple Europe Countries | 1.6% (1) |

| August | 6.3% (4) | Multiple Countries/Worldwide | 11.1% (7) |

| September | 3.2% (2) | ||

| October | 20.6% (13) | ||

| November | 7.9% (5) | ||

| December | 4.8% (3) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watson, K.E.; Schindel, T.J.; Barsoum, M.E.; Kung, J.Y. COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020099

Watson KE, Schindel TJ, Barsoum ME, Kung JY. COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharmacy. 2021; 9(2):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020099

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatson, Kaitlyn E., Theresa J. Schindel, Marina E. Barsoum, and Janice Y. Kung. 2021. "COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic" Pharmacy 9, no. 2: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020099

APA StyleWatson, K. E., Schindel, T. J., Barsoum, M. E., & Kung, J. Y. (2021). COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharmacy, 9(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020099