Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing in French Nursing Home Residents: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Data Source

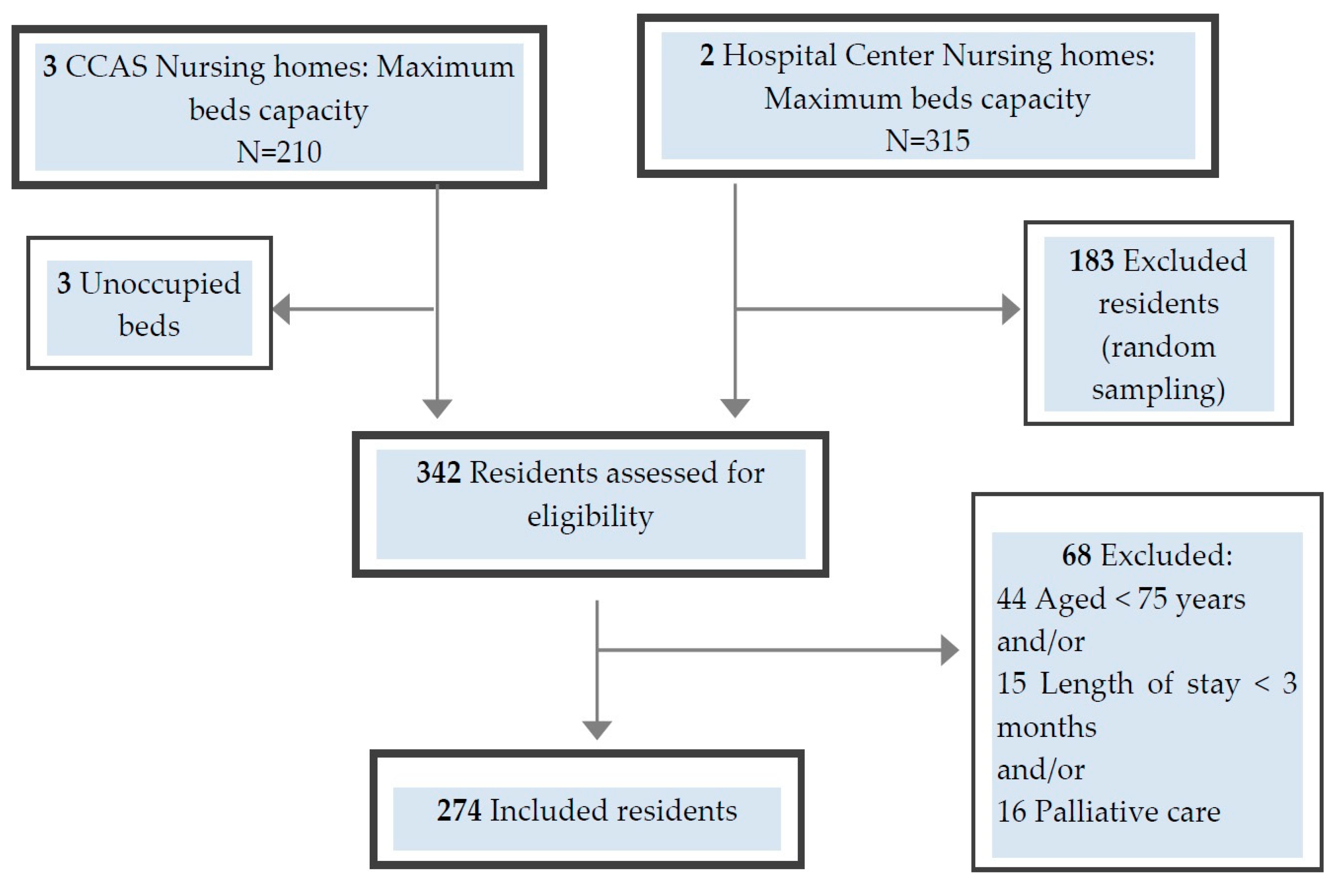

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Outcome Measure

2.6. Resident Characteristics

2.7. Nursing Home Characteristics

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of NHs and Study Population (Residents)

3.2. Characteristics of Drugs Prescription

3.3. Outcomes Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Components of PIDP | Drug Class | Non-Proprietary Name | Residents. No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug with an unfavorable benefit-to-risk ratio according to the Laroche list | |||

| Hypnotics and sedatives | Zolpidem a | 16 (5.9) | |

| Zopiclone b | 16 (5.9) | ||

| Lormetazepam c | 7 (2.6) | ||

| Clorazepate | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Anxiolytics | Bromazepam | 8 (3) | |

| Oxazepam d | 8 (3) | ||

| Hydroxyzine | 7 (2.6) | ||

| Diazepam | 4 (1.5) | ||

| Prazepam | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Levomepromazine | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Antihistaminics | Alimemazine | 8 (3) | |

| Oxomemazine | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Antipsychotics | Cyamemazine | 5 (1.8) | |

| Drug with questionable efficacy, according to the Laroche list | |||

| Non-steroids anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products | Diclofenac | 11 (4) | |

| Niflumic acid | 5 (1.8) | ||

| Chondroitin sulfate | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Anti-dementia drugs | Ginkgo folium § | 4 (1.5) | |

| Other anxiolytics | Etifoxine | 4 (1.5) | |

| Antivertigo | Betahistine e | 3 (1.1) | |

| Acetylleucine | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Peripheral vasodilators | Naftidrofuryl § | 2 (0.7) | |

| Other cardiac preparations | Trimetazidine | 1 (0.4) |

| Components of PIDP | Drug Class | Non-Proprietary Name | Residents. No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other Drug with an unfavorable benefit-to-risk ratio | |||

| Elderly | Cardiovascular system | Nitroglycerine | 8 (2.9) |

| Verapamil | 4 (1.5) | ||

| Ditilazem | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Tropatepine | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Nervous system | Paracetamol + opium + caffeine | 3 (1.1) | |

| Tropatepine | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Musculo–skeletal system | Allopurinol | 6 (2.2) | |

| Colchicine and opium association | 1 (0.4) | ||

| No psychiatric disease, no aggressivity | Nervous system | Risperidone | 3 (1.1) |

| Haloperidol | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Diabetes | Nervous system | Tramadol, paracetamol | 3 (1.1) |

| Dementia | Genito urinary system and sex hormones | Trospium | 1 (0.4) |

| Hypertension, heart failure | Nervous system | Paracetamol effervescent | 1 (0.4) |

| Off-label prescription | Nervous system | Clonazepam | 1 (0.4) |

| Components of PIDP | Non-Proprietary Name | Residents. No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Drug–disease contraindication | ||

| Severe renal impairment | Irbesartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 1 (0.4) |

| Spironolactone | 1 (0.4) | |

| Alendronique acid | 1 (0.4) | |

| Hydroclorothiazide | 1 (0.4) | |

| Diclofenac | 1 (0.4) | |

| Hyperkalemia | Spironolactone | 2 (0.7) |

| Glaucoma | Oxomemazine | 1 (0.4) |

| Solifenacine | 1 (0.4) | |

| Hydroxyzine | 1 (0.4) | |

| Active zoster | Prednisone | 1 (0.4) |

| Active depression | Rilmenidine | 1 (0.4) |

| Medical history of stroke | Tuaminoheptane | 1 (0.4) |

| Asthma | Codeine, chlorhydrate ethylmorphine | 1 (0.4) |

| Iron overload | Sodium feredetate | 1 (0.4) |

| Elderly | Fosfomycine | 1 (0.4) |

| Components of PIDP | Drug Class | Non-Proprietary Name | Residents. No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug–drug contraindication | |||

| Drugs which prolongs the QT interval | Citalopram with Domperidone | 2 (0.7) | |

| Citalopram with Haloperidol | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Escitalopram with Sotalol | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Escitalopram with Haloperidol | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Escitalopram with Domperidone | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Flecaine with Bisoprolol | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Significant drug–drug interaction | |||

| Increase in hemorrhagic risk | Acetyl-salicylique acid with Clopidogrel f | 1 (0.4) | |

| Reciprocal antagonism | Haloperidol with Levo-DOPA | 1 (0.4) | |

| Cyamemazine with Levo-DOPA | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Association not recommended, increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia | Haloperidol with Cyamemazine | 1 (0.4) | |

| Haloperidol with Levomepromazine | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Disorder of the cardiac conduction | Diltiazem with Carteolol | 1 (0.4) | |

| Absence of an effective treatment for a valid indication: an effective therapeutic had to be associated | |||

| Osteoporosis g | Vitamin D | 12 (4.4) | |

| Atrial Fibrillation | Antithrombotic agents (vitamin K antagonists or platelet aggregation inhibitors) | 5 (1.8) | |

| Secondary cardiovascular prevention post-Myocardial infarction | Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system and platelet aggregation inhibitors ± betablockers | 3 (1.1) | |

| Secondary cardiovascular prevention post stroke | Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 2 (0.7) | |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors and HMG CoA reductase inhibitors h | 1 (0.4) |

| Components of PIDP | Drug Class | Residents. No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Indication partially treated: it was necessary to add a synergistic drug or corrector | ||

| Heart failure | Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system or Betablockers | 13 (4.7) |

| Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system and/or diuretics | 3 (1.1) | |

| Betablockers or diuretics | 2 (0.7) | |

| Prevention opioid-induced constipation | Laxatives drug | 8 (2.9) |

| Secondary cardiovascular prevention post Myocardial infarction | HMG CoA reductase inhibitors h | 2 (0.7) |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 1 (0.4) | |

| Chronic obstructive arterial disease | Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 1 (0.4) |

| Indication partially treated: it was necessary to add a synergistic drug or corrector | ||

| Heart failure | Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system or Betablockers | 13 (4.7) |

| Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system and/or diuretics | 3 (1.1) | |

| Betablockers or diuretics | 2 (0.7) | |

| Prescribing without valid medical indication | ||

| Proton pump inhibitors | 28 (10.2) | |

| Antithrombotic Agents | 18 (6.6) | |

| Diuretics | 12 (4.4) | |

| Anti-dementia drugs | 9 (3.3) | |

| Drugs for obstructive airway diseases (adrenergics and others) | 5 (1.8) | |

| Antiarrythmics (class I and III) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Anti-epileptics | 4 (1.5) | |

| Betablockers | 3 (1.1) | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 3 (1.1) | |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | 3 (1.1) |

References

- Legrain, S. Consommation Médicamenteuse Chez Le Sujet Âgé: Consommation, Prescription, Iatrogénie Et Observance; Haute Autorité de Santé: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldo, L.; Cano, F.G.; Damasceno, G.S.; Rozenfeld, S. Inappropriate medication use among the elderly: A systematic review of administrative databases. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anrys, P.M.S.; Strauven, G.C.; Foulon, V.; Degryse, J.-M.; Henrard, S.; Spinewine, A. Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Belgian Nursing Homes: Prevalence and Associated Factors. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Prendre En Charge Une Personne Agée Polypathologique En Soins Primaires; Haute Autorité de Santé: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D.T.; Kasper, J.D.; Potter, D.E.B.; Lyles, A.; Bennett, R.G. Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinewine, A.; Schmader, K.E.; Barber, N.; Hughes, C.; Lapane, K.L.; Swine, C.; Hanlon, J.T. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: How well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 2007, 370, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, D.M.; Cooper, J.W.; Wade, W.E.; Waller, J.L.; Maclean, J.R.; Beers, M.H. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.-L.; Charmes, J.-P.; Merle, L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: A French consensus panel list. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 63, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P.; Ryan, C.; Byrne, S.; Kennedy, J.; O’Mahony, D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2008, 46, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.O.; Dramé, M.; Guignard, B.; Mahmoudi, R.; Payot, I.; Latour, J.; Schmitt, E.; Pepersack, T.; Vogt-Ferrier, N.; Hasso, Y.; et al. Les Critères STOPP/START.v2: Adaptation en langue française. Npg. Neurol. Psychiatr. Gériatrie 2015, 15, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Indicateurs de Pratique Clinique (IPC PMSA). Available online: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_1250626/indicateurs-de-pratique-clinique-ipc (accessed on 16 July 2015).

- Hanlon, J.; Schmader, K. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Prescrire Chez Le Sujet Agé, Programme PMSA; Haute Autorité de Santé: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Basger, B.J.; Chen, T.F.; Moles, R.J. Validation of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, R. ARMOR: A tool to evaluate polypharmacy in elderly persons. Ann. Long Term Care 2009, 17, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S.; Schwemm, A.K.; Reist, J.; Cantrell, M.; Andreski, M.; Doucette, W.R.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Farris, K.B. Pharmacists’ and pharmacy students’ ability to identify drug-related problems using TIMER (Tool to Improve Medication in the Elderly via Review). Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cool, C.; Cestac, P.; Laborde, C.; Lebaudy, C.; Rouch, L.; Lepage, B.; Vellas, B.; de Barreto, P.S.; Rolland, Y.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M. Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing and Associated Factors in Nursing Homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 850.e1–850.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrain, S.; Tubach, F.; Bonnet-Zamponi, D.; Lemaire, A.; Aquino, J.-P.; Paillaud, E.; Taillandier-Heriche, E.; Thomas, C.; Verny, M.; Pasquet, B.; et al. A New Multimodal Geriatric Discharge-Planning Intervention to Prevent Emergency Visits and Rehospitalizations of Older Adults: The Optimization of Medication in AGEd Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet-Zamponi, D.; d’Arailh, L.; Konrat, C.; Delpierre, S.; Lieberherr, D.; Lemaire, A.; Tubach, F.; Lacaille, S.; Legrain, S. The Optimization of Medication in AGEd Study Group. Drug-Related Readmissions to Medical Units of Older Adults Discharged from Acute Geriatric Units: Results of the Optimization of Medication in AGEd Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseviers, M.M.; Vander Stichele, R.R.; Van Bortel, L. Quality of prescribing in Belgian nursing homes: An electronic assessment of the medication chart. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment. Available online: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Laroche, M.-L.; Bouthier, F.; Merle, L.; Charmes, J.-P. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: Interest of a list adapted to the French medical practice. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2009, 30, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.-O.; Hasso, Y.; Belmin, J.; Payot, I.; Baeyens, J.-P.; Vogt-Ferrier, N.; Gallagher, P.; O’Mahony, D.; Michel, J.-P. STOPP-START: Adaptation of a French language screening tool for detecting inappropriate prescriptions in older people. Can. J. Public Health 2009, 100, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P.; O’Mahony, D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): Application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.J.; Gallagher, P.; Ryan, C.; O’mahony, D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment) an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing 2007, 36, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Société Française de Pharmacie Clinique. Liste Nationale des Médicaments Ecrasables et L’ouverture des Gélules. Available online: http://geriatrie.sfpc.eu/application/choose (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Derouesné, C.; Poitreneau, J.; Hugonot, L.; Kalafat, M.; Dubois, B.; Laurent, B. Mini-Mental State Examination: A Useful Method for the Evaluation of the Cognitive Status of Patients by the Clinician. Consensual French Version. Presse Med. 1999, 28, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Renom-Guiteras, A.; Meyer, G.; Thürmann, P.A. The EU(7)-PIM list: A list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.J.; O’Keefe, N.; O’Connor, K.A.; O’Mahony, D. Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: A comparison of the Beers criteria and the improved prescribing in the elderly tool (IPET) in acutely ill elderly hospitalized patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2006, 31, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, L.; Fastbom, J.; Laroche, M.-L.; Johnell, K. Potentially inappropriate drug use in older people: A nationwide comparison of different explicit criteria for population-based estimates. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 80, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongue, B.; Laroche, M.L.; Gutton, S.; Colvez, A.; Guéguen, R.; Moulin, J.J.; Merle, L. Potentially inappropriate drug prescription in the elderly in France: A population-based study from the French National Insurance Healthcare system. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, H.; Blocher, C. Etude PREMS Pilulier Mono-Médicaments de 28 Jours et Consommation Médicamenteuse Chez 39-892 Sujets Agés en EHPAD. Available online: http://www.medissimo.fr/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/3-Pilulier-mono-m%C3%A9dicaments-de-28-jours-et-consommation-m%C3%A9dicamenteuse-chez-39-892-sujets-ag%C3%A9s-en-EHPAD.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2015).

- Onder, G.; Liperoti, R.; Fialova, D.; Topinkova, E.; Tosato, M.; Danese, P.; Gallo, P.F.; Carpenter, I.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Gindin, J.; et al. Polypharmacy in Nursing Home in Europe: Results from the SHELTER Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67A, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechevallier-Michel, N.; Gautier-Bertrand, M.; Alprovitch, A.; Berr, C.; Belmin, J.; Legrain, S.; Saint-Jean, O.; Tavernier, B.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Fourrier-Réglat, A.; et al. Frequency and risk factors of potentially inappropriate medication use in a community-dwelling elderly population: Results from the 3C Study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 60, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, P.L. Psychotropic Medication Use among Older Adults: What All Nurses Need to Know. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 35, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatoire Régional de la Santé de Midi Pyrénées. Analyse des Rapports D’activité Médicale 2013 des EHPAD de Midi-Pyrénées; Agence régionale de santé Occitanie: Toulouse, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fossey, J. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, I.; Claesson, C.B.; Westerholm, B.; Nilsson, L.G.; Svarstad, B.L. The impact of regular multidisciplinary team interventions on psychotropic prescribing in Swedish nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998, 46, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcher, A.; Hily, S.; Boureau, A.S.; Chapelet, G.; Berrut, G.; de Decker, L. Multimorbidities and Overprescription of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Older Patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarchow-MacDonald, A.A.; Mangoni, A.A. Prescribing patterns of proton pump inhibitors in older hospitalized patients in a Scottish health board. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seite, F.; Delelis-Fanien, A.-S.; Valero, S.; Pradère, C.; Poupet, J.-Y.; Ingrand, P.; Paccalin, M. Compliance with Guidelines for Proton Pump Inhibitor Prescriptions in a Department of Geriatrics. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 2169–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.J.; Hernández–Díaz, S.; García Rodríguez, L.A. Acid Suppressants Reduce Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients on Antithrombotic or Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.A.; Oldfield, E.C. Reported Side Effects and Complications of Long-term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use: Dissecting the Evidence. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, R.S. Heart failure. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2007, 2007, 0204. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Chronic Heart Failure in Adults: Management | 1-Guidance | Guidance and Guidelines | NICE; The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.S.; Brown, D.L.; Becker, R.C. Low-Dose Aspirin in Patients with Stable Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Laroche, C.; Dan, G.-A.; Santini, M.; Kalarus, Z.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Ioachim, P.M.; Tica, O.; Boriani, G.; Cimaglia, P.; et al. ‘Real-World’ Antithrombotic Treatment in Atrial Fibrillation: The EORP-AF Pilot Survey. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 519–529.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.L.; Smyth, S.; Montalescot, G.; Steinhubl, S.R. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2007, 297, 2018–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdenet, G.; Giraud, S.; Artur, M.; Dutertre, S.; Dufour, M.; Lefèbvre-Caussin, M.; Proux, A.; Philippe, S.; Capet, C.; Fontaine-Adam, M.; et al. Impact of recommendations on crushing medications in geriatrics: From prescription to administration. Fundam. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 29, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, L.J.M.; Coster, G.; Gamble, G.D.; McCormick, R.N. The General Practitioner-Pharmacist Collaboration (GPPC) study: A randomised controlled trial of clinical medication reviews in community pharmacy: The GP-Pharmacist Collaboration study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Prévention Cardio-Vasculaire: Le Choix De La Statine La Mieux Adaptée Dépend De Son Efficacité Et De Son Efficience—Avis d’efficience HAS—Février 2012; Haute Autorité de Santé: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Nursing Home Characteristics | CCAS-NH | H-NH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Pharmacy for internal usage | No (community pharmacist) | No (community pharmacist) | No (community pharmacist) | Yes | Yes |

| Maximum capacities (beds) | 60 | 65 | 85 | 195 | 120 |

| Special care unit | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Presence of a nurse at night | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Computerized medical charts | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| GP per 100 beds | 25 | 18.5 | 8.2 | 1 | 19.2 |

| Nurses per 100 beds | 6.7 | 6.1 | 8.2 | Δ | 7.5 |

| Resident Main Characteristics | Total n = 274 | % | Mean | SD | Median | p25% | p75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||||||

| Age (year) | 88.9 | 6.2 | |||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Men | 67 | 24.5 | |||||

| Dementia | |||||||

| MMSE scoreΔ | 15 | 9 | 21 | ||||

| Biological data | |||||||

| Renal functionΔ(Cockcroft–Gault formula) | 44.2 | 18.3 | |||||

| Hospitalization in the previous 12 monthsΔ | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Falls in the last 12 monthsΔ | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Most common comorbidities | |||||||

| Hypertension | 177 | 64.6 | |||||

| Dementia (Alzheimer’s disease and other) | 146 | 53.3 | |||||

| Depression | 130 | 47.5 | |||||

| Arthrosis | 62 | 22.6 | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 61 | 22.3 | |||||

| Hypothyroidism | 55 | 20.1 | |||||

| Diabetes | 54 | 19.7 | |||||

| Osteoporosis | 50 | 18.3 | |||||

| Psychosis, excluding depression | 43 | 15.7 | |||||

| Stroke | 42 | 15.3 | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 37 | 13.5 | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 36 | 13.1 | |||||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 34 | 12.4 | |||||

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 30 | 11 |

| Drug | Total n = 274 | % |

|---|---|---|

| No polypharmacy (0–5 drugs) | 61 | 22.3 |

| Polypharmacy (6–8 drugs) | 94 | 34.3 |

| Hyperpolypharmacy (≥9 drugs) | 119 | 43.4 |

| Number of patients with a least one prescription of the anatomical class | ||

| N Nervous System | 255 | 93.1 |

| A Alimentary tract and metabolism | 241 | 88 |

| C Cardiovascular System | 201 | 73.4 |

| B Blood and blood forming organs | 146 | 53.3 |

| H Systemic hormones, excluding sex hormones | 60 | 21.9 |

| Therapeutic class | ||

| N05 Psycholeptics | 204 | 74.5 |

| N02 Analgesics | 173 | 63.1 |

| A06 Drugs for constipation | 139 | 50.7 |

| N06 Psychoanaleptics | 137 | 50 |

| B01 Antithrombotic Agents | 132 | 48.2 |

| Potential Drug-Related Problems | Residents n = 274 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome measure (at least one PIDP) | 212 | 77.4 |

| Non-compliance to the various consensus | ||

| Drug(s) with a non-favorable benefit-to-risk ratio | ||

| According to the Laroche list | 84 | 30.7 |

| According to clinical and biological residents’ data | 38 | 13.9 |

| Presence of drug(s) with questionable efficacy | ||

| According to the Laroche list | 34 | 12.4 |

| Absolute contraindication | 20 | 7.3 |

| Significant drug–drug interaction | 7 | 2.6 |

| Underdosing | 11 | 4 |

| Overdosing | 55 | 20.1 |

| Concomitant prescription of drugs from the same therapeutic class | 74 | 27 |

| Concomitant prescription of psychotropic drugs ≥3 † : | 33 | 12 |

| ≥2 antipsychotics † | 7 | 2.6 |

| ≥2 benzodiazepines † | 11 | 4 |

| ≥2 antidepressants † | 1 | 0.4 |

| Concomitant prescription of diuretics: ≥2 † | 4 | 1.5 |

| Concomitant prescription of antihypertensive drugs: ≥4 † | 7 | 2.6 |

| Other redundancies | 11 | 4 |

| Drugs without any valid indication | 82 | 30 |

| Under-prescribing | 62 | 22.6 |

| Absence of an effective treatment for a condition for which one or several drug classes have demonstrated their efficacy | 20 | 7.3 |

| Absence of a synergistic drug or corrector | 42 | 15.3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qassemi, S.; Pagès, A.; Rouch, L.; Bismuth, S.; Stillmunkes, A.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M.; McCambridge, C.; Cool, C.; Cestac, P. Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing in French Nursing Home Residents: An Observational Study. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030133

Qassemi S, Pagès A, Rouch L, Bismuth S, Stillmunkes A, Lapeyre-Mestre M, McCambridge C, Cool C, Cestac P. Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing in French Nursing Home Residents: An Observational Study. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(3):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030133

Chicago/Turabian StyleQassemi, Soraya, Arnaud Pagès, Laure Rouch, Serge Bismuth, André Stillmunkes, Maryse Lapeyre-Mestre, Cécile McCambridge, Charlène Cool, and Philippe Cestac. 2020. "Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing in French Nursing Home Residents: An Observational Study" Pharmacy 8, no. 3: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030133

APA StyleQassemi, S., Pagès, A., Rouch, L., Bismuth, S., Stillmunkes, A., Lapeyre-Mestre, M., McCambridge, C., Cool, C., & Cestac, P. (2020). Potentially Inappropriate Drug Prescribing in French Nursing Home Residents: An Observational Study. Pharmacy, 8(3), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030133