The Relevancy of paracetamol and Breastfeeding Post Infant Vaccination: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

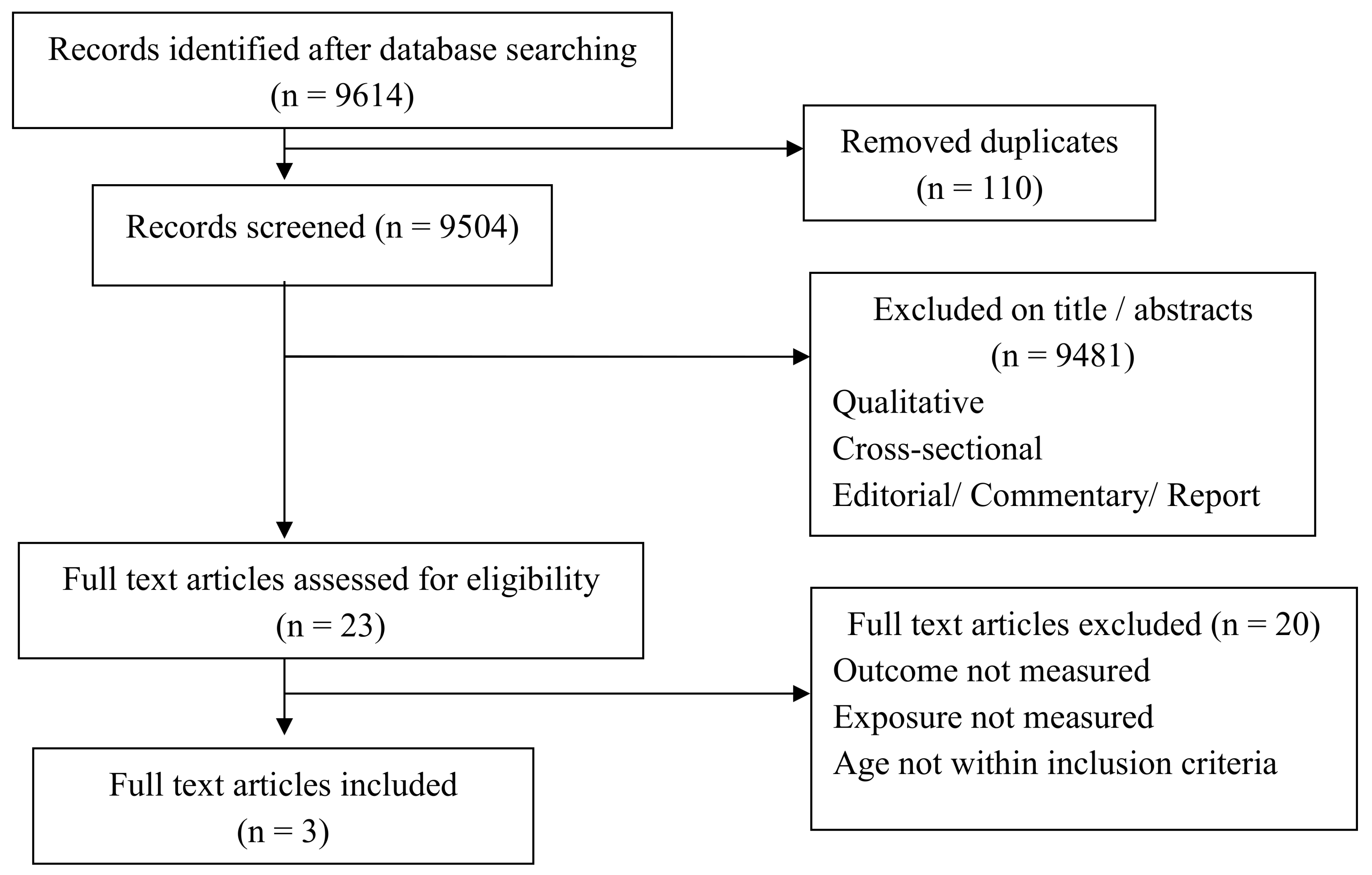

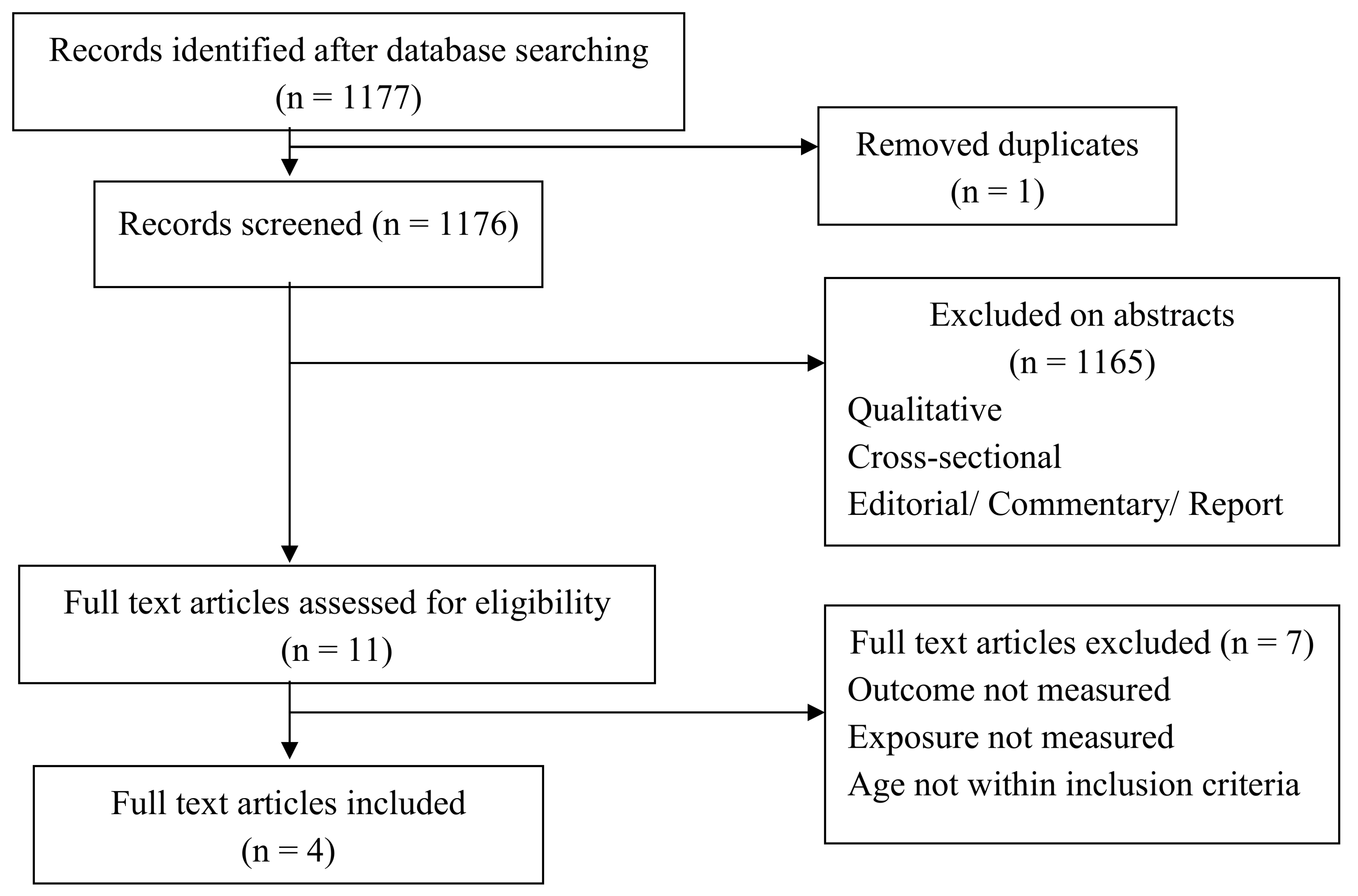

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection: Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection: Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5. Primary Outcome

2.6. Validity Assessment

2.7. Data Abstraction

2.8. Study Characteristics

2.9. Data Synthesis

2.10. Secondary Outcomes

3. Results

3.1. Effectiveness of Breastfeeding as an Analgesic Property for Pain Following Childhood Vaccination

3.1.1. Study Descriptions

3.1.2. Study Characteristics

3.2. Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

3.3. Effects of Breastfeeding Post Infants Vaccination

3.4. Effectiveness of Prophylactic Paracteamol’s Antipyretic and Analgesic Properties and Its Safety for Fever Following Childhood Immunization

3.4.1. Study Descriptions

3.4.2. Study Characteristics

3.5. Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

3.6. Effect of Prophylactic PCM for Fever and Pain Following Childhood Immunization

3.7. Safety of Prophylactic paracetamol Post Infant Vaccination

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Recommendation for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database Searches | Items Measure | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Ovid LWW Total Access Collection and Medline, CINAHL Plus with Fulltext, Science Direct, Proquest Dissertations and Theses, Proquest Education Journal and Proquest Health and Medical Complete (data collected from published paper from 1987 until 2017) | (1) Pain (2) Breastfeeding | ‘breastfeeding; pain or analgesia; following or post; immunization or vaccination; infant or newborn’ |

| (3) Fever and pain (4) paracetamol | ‘feverish or febrile or fever; breastfeeding; temperature decrease; antipyretic; analgesic; following or post; immunization or vaccination; infant or newborn; antibody’ |

| No. | Author; Country; Year of Publication | Research Design | Study Population; Care Recipient % Boys; Care Recipient Age Mean (SD) | Sample Size: Baseline; Follow-Up | Exposure Measure | Outcome Measure | Quality Score (%) | Statistical Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Modarres, Jazayeri, Rahnama, Montazeri, Iran, 2013 [Funding Source: Instituitional Review Board of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Full term neonates breastfed 2 minutes before, during and after Hepatitis B immunization or held in mothers’ arms but not fed; 83% boys; 39.4 (1.2) in control group and 39.1 (1.3) in experimental group weeks | 130; 130; 130 | Pain score measured using DAN scale (Facial expressions, limb movements and vocal expression) | Pain score | 75 |

| Breastfeeding reduces pain and is effective way for pain relief during Hepatitis B injection |

| 2. | Razek, El-Dein, Jordan, 2009 [Funding Source: None] | Quasi experiment: Counter balanced (cross-over) | Infants either breastfed or not; 64.2% boys; 1–12 months of age | 120; 120; 120 |

|

| 75 |

| Breastfeeding and skin to skin contact significantly reduced the pain in infants receiving immunization. Pain Score also showed lesser in breastfeeding group. |

| 3. | Efe, Ozer, Turkey, 2007 [Funding Source: Akdeniz University Scientific Research Project Unit] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Healthy infants receiving 2nd, 3rd or 4th immunization of IM DTP either breastfed before, during and after injection or given not breastfed; 56.1% boys; 3.08 ± 1.32 months control, 2.79 ± 1.13 months breastfed | 66; 66; 66 |

|

| 83 |

| Breastfeeding, maternal holding, and skin to skin contact significantly reduced crying time in infants receiving immunization injection for DTP |

| No. | Author; Country; Year of Publication | Research Design | Study Population; Care Recipient % Boys; Care Recipient Age Mean (SD) | Sample Size: Baseline; Follow-Up | Exposure Measure | Outcome Measure | Quality Score | Statistical Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Rose, Juergens, Schmoele-Thoma, Gruber, Baker; Germany; 2013 [Funding Source: Pfizer Inc.] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Healthy infants who received three-dose infant series of PCV-7 and DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib plus a toddler dose either received prophylactic paracetamol at vaccination and at 6–9 h interval thereafter or a control group that received no paracetamol; 51.5% boys; 2.4–11.7 months | 301; 286; 245 |

|

| 83 |

|

|

| 2. | Jackson, Peterson, Dunn, Hambidge, Dunstan, Starkovich, Yu, Benoit, Dominguez-Islas, Carste, Benson, Nelson; Czech Republic; 2011 [Funding Source: Centre for Disease Control and Preventive (CDC) through America’s Health Insurance Plans] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Children received up to five PCM doses (10–15 mg/kg) or placebo following routine vaccinations; 51% boys; 31 weeks to 69 weeks | 374; 352; 234 |

|

| 83 |

| Acetaminophen may reduce risk of post-vaccination fussiness but not reduce fever |

| 3. | Prymula, Siegrist, Chlibek, Zemlickova, Vackova, Smetana, Lommel, Kaliskova, Borys, Schuerman; Czech Republic; 2009 [Funding Source: GSK Biologicals] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Children received 3 prophylactic PCM doses every 6 to 8 hours in first 24 h, or no prophylactic PCM after each vaccination with PHiD-CV co-administered with DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib and oral human rotavirus vaccines; 51% boys; mean aged at time of 1st dose was 12.3 weeks (SD 2.13). | 459; 459; 414 |

|

| 88 |

| Prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at time of vaccination should not routinely recommended, although febrile reactions significantly decreased since antibody responses to several antigens were reduced significantly |

| 4. | Uhari, Hietala, Viljanen; Finland; 1988 [Funding Source: None] | True experiment: Placebo controlled trial | Healthy infants vaccinated with DTP or DTP-inactivated polio vaccine receive placebo or 75 mg PCM 4 h after vaccination; not mentioned; 5 months | 295; 263; 263 |

|

| 65 |

| Acetaminophen in a single dose schedule is ineffective in decreasing post-vaccination fever and antibody response also showed no significant difference in control and experimental groups |

References

- American Pharmacists Association. Acetominophen. In Drug Information Handbook; Lexi-comp: Hudson, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bahagian Pembangunan Kesihatan Keluarga. Panduan Program Imunisasi Kebangsaan Kanak-Kanak Untuk Anggota Kejururawatan; Kementerian Kesihatan: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2008.

- College of Paediatrics. Malaysian Immunization Manual; Academy of Medicine Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.A.; Peterson, D.; Dunn, J.; Hambidge, S.J.; Dunstan, M.; Starkovich, P.; Yu, O.; Benoit, J.; Dominguez-Islas, C.P.; Carste, B.; et al. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Acetominophen for Prevention of Post-Vaccination Fever in infants. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddock, C. Routine Use of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) After Vaccination Not Recommended for Infants, Study. Medical News Today, 19 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, P.; Siegrist, C.A.; Chlibek, R.; Zemlickova, H.; Vackova, M.; Smetana, J.; Lommel, P.; Kaliskova, E.; Borys, D.; Schuerman, L. Effect of prophylactic Paracetamol administration at time of vaccination on febrile reactions and antibody responses in children: Two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2009, 374, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Atkinson, E.J.; O’fallon, W.M.; Melton, C.J., III. Incidence of Clinically Diagnosed Vertebral Fractures: A Population-Based Study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989; Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic and Foundation: Rochester, MN, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz, D.G.; Nelson, K.B.; Ellenberg, J.H. Seizures following childhood immunization. J. Pediatr. 1982, 102, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE. Feverish Illness in Children Assessment and Initial Management in Children Younger Than 5 Years; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Manchester, UK, 2013.

- Katrin, S.K.; Michael, M.; Michael, B.; Marcy, C.J.; Ron, D.; John, H.; David, N.; Edward, R.; the Brighton Collaboration Fever Working Group. Fever after Immunization: Current Comcepts and Improved Future Scientific Understanding; Infectious Diseases Society of America: Arlington, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.R.; Panighari, I.; Naik, S.S. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janice, E.; Sullivan, M.D.; Henry, C.; Farrar, M.D.; the Section on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, and Committee on Drugs. Clinical Report: Fever and Antipyretic Use in Children; American Academy of Peadiatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coomarasamy, A.; Taylor, R.; Khan, K.S. A systematic review of postgraduate teaching in evidence-based medicine and critical appraisal. Med. Teach. 2003, 25, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisacane, A.; Continision, P.; Palma, O.; Cataldo, S.; Michele, F.D.; Vairo, U. Breastfeeding and risk for fever after immunization. Peadiatrics 2010, 125, e1448–e1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, P.J.; Mathew, J.L. Assessment and management of pain in infants. Postgrad. Med. J. 2003, 79, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.A.; Juergens, C.; Schmoele-Thoma, B.; Gruber, W.C.; Baker, S.; Zielen, S. An open-label randomised clinical trial of prophylactic paracetamol coadministered with 7-valent penumococcal conjugate vaccine and hexavalent diphteria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, 3-component acellular pertusis, hepatitis B, inactivated poliovirus, and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. BMC Peadiatr. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhari, M.; Hietala, J.; Viljanen, M.K. Effect of prophylactic acetaminophen administration on reaction to DTP vaccination. Acta Paedistr. Scand. 1988, 77, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.; Kirubakaran, C.; Scott, J.X. Intermittent clobazam therapy in febrile seizures. Indian J. Peadiatr. 2005, 72, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suleiman, N.; Shamsudin, S.H.; Mohd Rus, R.; Draman, S.; Taib, M.N.A. The Relevancy of paracetamol and Breastfeeding Post Infant Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6020027

Suleiman N, Shamsudin SH, Mohd Rus R, Draman S, Taib MNA. The Relevancy of paracetamol and Breastfeeding Post Infant Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy. 2018; 6(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuleiman, Nurain, Siti Hadijah Shamsudin, Razman Mohd Rus, Samsul Draman, and Mai Nurul Ashikin Taib. 2018. "The Relevancy of paracetamol and Breastfeeding Post Infant Vaccination: A Systematic Review" Pharmacy 6, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6020027

APA StyleSuleiman, N., Shamsudin, S. H., Mohd Rus, R., Draman, S., & Taib, M. N. A. (2018). The Relevancy of paracetamol and Breastfeeding Post Infant Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy, 6(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6020027