The Second Round of the PHAR-QA Survey of Competences for Pharmacy Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Questions were simplified, especially regarding matters of:

- .

- treating one topic per question;

- .

- simplifying English expressions.

- The section on the subject areas as given in the directive 2013/55/EU (physics, biology, etc.) [3] was removed as these were not considered as “competences”.

- Questions on research and industrial pharmacy were reworked given the level for which the PHAR-QA framework is intended: five-year pharmacy degree, not postgraduate specialisation.

- Emphasis was placed on “being aware of”, rather than “capable of doing”. We used the terms “knowledge”, i.e., “being aware of”, and “ability”, i.e., “capable of doing”.

- The second version of the European Delphi questionnaire included an open-ended question for suggestions on matters not proposed that should be treated and other comments.

2. Experimental Section

Short Description of the Experimental Paradigm and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Presentation of the Results of the Second Round in the European Pharmacy Community and Comparison with the Results of the First Round

3.2. Results for the Ranking of Competences and for Consensus in the Second Round

- (1)

- Working environment (six comments). Example: emphasis should be put on the community pharmacy and hospital pharmacy setting.

- (2)

- Team work and the definition of the responsibility of the pharmacists within the health team (14 comments). Example: clearly know what the pharmacist is responsible for. One community pharmacist suggested that pharmacists were ideally suited to be the “coordinator” of the health team.

- (3)

- Legal and other limits to the pharmacist’s responsibility (seven comments). Examples: diagnosis is the responsibility of doctors; pharmacists in Latvia mostly work in chain-pharmacies…where owners and managers have no pharmaceutical education.

- (4)

- Use of information technology (four comments). Example: ability to find appropriate sources and use electronic platforms.

4. Conclusions

- A good starting point for the adoption of the competence framework is to match existing curriculum of a department to the framework; this approach has previously been used to match outcomes to curricula, and the methodology has been published [23].

- Building a curriculum based on the PHAR-QA competence framework could be guided by the following:

- ○

- Core curriculum: the fundamental, bachelor curriculum could be based, amongst others, on the clusters of competences with the highest ranking scores, viz, 12: “need for drug treatment”, 13: “drug interactions” and 16: “provision of information and service”.

- ○

- Specialisation in the advanced, master curriculum could include, for instance,

- ◾

- for community pharmacists: Competences 32 “ability to identify and prioritise drug-drug interactions and advise appropriate changes to medication” and 34 “ability to identify and prioritise drug-disease interactions (e.g., NSAIDs in heart failure) and advise on appropriate changes to medication”

- ◾

- for hospital pharmacists: Competences 36 “ability to recommend interchangeability of drugs based on in-depth understanding and knowledge of bioequivalence, bio-similarity and therapeutic equivalence of drugs” and 50 “ability to contribute to the cost effectiveness of treatment by collection and analysis of data on medicines’ use”

- ◾

- for industrial pharmacists; Competences 21 “knowledge of good manufacturing practice and of good laboratory practice” and 23 “knowledge of drug registration, licensing and marketing”

- ○

- The ways in which the various competences are taught are diverse. For instance, for personal competence Clusters 8 “values” and 9 “communication and organisational skills”, the role of the traineeship monitor is uppermost. The way in which this is to be developed needs to be harmonized within the EU, but the finer details would be up to individual faculties.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

| Question | Competence | Community | Industrial | Hospital | Others | Students | Academics | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7. Personal competences: learning and knowledge. | 88 | |||||||

| 1 | 1. Ability to identify learning needs and to learn independently (including continuous professional development (CPD)). | 90 | 91 | 97 | 87 | 82 | 88 | 89 |

| 2 | 2. Ability to apply logic to problem solving. | 93 | 99 | 97 | 89 | 93 | 98 | 95 |

| 3 | 3. Ability to critically appraise relevant knowledge and to summarise the key points. | 91 | 97 | 97 | 87 | 88 | 95 | 92 |

| 4 | 4. Ability to evaluate scientific data in line with current scientific and technological knowledge. | 78 | 86 | 95 | 76 | 81 | 93 | 85 |

| 5 | 5. Ability to apply preclinical and clinical evidence-based medical science to pharmaceutical practice. | 77 | 70 | 94 | 71 | 82 | 87 | 80 |

| 6 | 6. Ability to apply current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice. | 88 | 87 | 94 | 84 | 77 | 85 | 86 |

| 8. Personal competences: values. | 89 | |||||||

| 7 | 1. A professional approach to tasks and human relations. | 93 | 90 | 88 | 84 | 87 | 89 | 88 |

| 8 | 2. Ability to maintain confidentiality. | 96 | 93 | 97 | 94 | 87 | 90 | 93 |

| 9 | 3. Ability to take full responsibility for patient care. | 92 | 90 | 94 | 89 | 88 | 90 | 91 |

| 10 | 4. Ability to inspire the confidence of others in one's actions and advice. | 85 | 90 | 91 | 82 | 80 | 83 | 85 |

| 11 | 5. Knowledge of appropriate legislation and of ethics. | 90 | 94 | 90 | 89 | 78 | 90 | 88 |

| 9. Personal competences: communication and organisational skills. | 79 | |||||||

| 12 | 1. Ability to communicate effectively, both oral and written, in the locally relevant language. | 95 | 86 | 94 | 89 | 89 | 94 | 91 |

| 13 | 2. Ability to effectively use information technology. | 89 | 81 | 92 | 84 | 82 | 88 | 86 |

| 14 | 3. Ability to work effectively as part of a team. | 91 | 88 | 95 | 83 | 87 | 85 | 88 |

| 15 | 4. Ability to implement general legal requirements that impact upon the practice of pharmacy (e.g., health and safety legislation, employment law). | 84 | 83 | 84 | 77 | 74 | 80 | 80 |

| 16 | 5. Ability to contribute to the training of staff. | 76 | 76 | 88 | 67 | 66 | 67 | 73 |

| 17 | 6. Ability to manage risk and quality of service issues. | 80 | 93 | 90 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 83 |

| 18 | 7. Ability to identify the need for new services. | 72 | 63 | 84 | 63 | 69 | 63 | 69 |

| 19 | 8. Ability to understand a business environment and develop entrepreneurship. | 69 | 67 | 63 | 56 | 60 | 44 | 60 |

| 10. Personal competences: research and industrial pharmacy. | 66 | |||||||

| 20 | 1. Knowledge of design, synthesis, isolation, characterisation and biological evaluation of active substances. | 44 | 58 | 41 | 48 | 66 | 63 | 53 |

| 21 | 2. Knowledge of good manufacturing practice and of good laboratory practice. | 65 | 89 | 73 | 78 | 81 | 76 | 77 |

| 22 | 3. Knowledge of European directives on qualified persons. | 56 | 84 | 57 | 61 | 57 | 51 | 61 |

| 23 | 4. Knowledge of drug registration, licensing and marketing. | 54 | 87 | 60 | 64 | 68 | 67 | 67 |

| 24 | 5. Knowledge of the importance of research in pharmaceutical development and practice. | 68 | 78 | 74 | 62 | 78 | 81 | 74 |

| 11. Patient care competences: patient consultation and assessment. | 75 | |||||||

| 25 | 1. Ability to interpret basic medical laboratory tests. | 70 | 60 | 86 | 77 | 83 | 79 | 76 |

| 26 | 2. Ability to perform appropriate diagnostic tests, e.g., measurement of blood pressure or blood sugar. | 69 | 51 | 49 | 63 | 81 | 59 | 62 |

| 27 | 3. Ability to recognise when referral to another member of the healthcare team is needed. | 93 | 81 | 86 | 84 | 91 | 90 | 87 |

| 12. Patient care competences: need for drug treatment. | 85 | |||||||

| 28 | 1. Ability to retrieve and interpret information on the patient’s clinical background. | 84 | 72 | 87 | 78 | 89 | 78 | 81 |

| 29 | 2. Ability to compile and interpret a comprehensive drug history for an individual patient. | 86 | 71 | 93 | 86 | 89 | 81 | 84 |

| 30 | 3. Ability to identify non-adherence to medicine therapy and make an appropriate intervention. | 91 | 76 | 96 | 88 | 89 | 87 | 88 |

| 31 | 4. Ability to advise to physicians on the appropriateness of prescribed medicines and, in some cases, to prescribe medication. | 83 | 74 | 93 | 88 | 90 | 89 | 86 |

| 13. Patient care competences: drug interactions. | 92 | |||||||

| 32 | 1. Ability to identify and prioritise drug-drug interactions and advise appropriate changes to medication. | 96 | 89 | 95 | 94 | 96 | 94 | 94 |

| 33 | 2. Ability to identify and prioritise drug-patient interactions, including those that prevent or require the use of a specific drug, based on pharmaco-genetics, and advise on appropriate changes to medication. | 90 | 85 | 92 | 85 | 92 | 89 | 89 |

| 34 | 3. Ability to identify and prioritise drug-disease interactions (e.g., NSAIDs in heart failure) and advise on appropriate changes to medication. | 96 | 91 | 93 | 92 | 97 | 95 | 94 |

| 14. Patient care competences: drug dose and formulation. | 76 | |||||||

| 35 | 1. Knowledge of the bio-pharmaceutical, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic activity of a substance in the body. | 75 | 76 | 86 | 78 | 82 | 88 | 81 |

| 36 | 2. Ability to recommend interchangeability of drugs based on in-depth understanding and knowledge of bioequivalence, bio-similarity and therapeutic equivalence of drugs. | 79 | 79 | 96 | 79 | 83 | 86 | 84 |

| 37 | 3. Ability to undertake a critical evaluation of a prescription ensuring that it is clinically appropriate and legally valid. | 83 | 77 | 95 | 89 | 87 | 86 | 86 |

| 38 | 4. Knowledge of the supply chain of medicines thus ensuring timely flow of quality drug products to the patient. | 69 | 73 | 85 | 75 | 69 | 66 | 73 |

| 39 | 5. Ability to manufacture medicinal products that are not commercially available. | 46 | 70 | 57 | 52 | 51 | 57 | 55 |

| 15. Patient care competences: patient education. | 80 | |||||||

| 40 | 1. Ability to promote public health in collaboration with other professionals within the healthcare system. | 82 | 76 | 78 | 75 | 79 | 73 | 77 |

| 41 | 2. Ability to provide appropriate lifestyle advice to improve patient outcomes (e.g., advice on smoking, obesity, etc.). | 81 | 72 | 76 | 75 | 85 | 76 | 78 |

| 42 | 3. Ability to use pharmaceutical knowledge and provide evidence-based advice on public health issues involving medicines. | 89 | 80 | 84 | 85 | 88 | 85 | 85 |

| 16. Patient care competences: provision of information and service. | 87 | |||||||

| 43 | 1. Ability to use effective consultations to identify the patient's need for information. | 82 | 65 | 87 | 82 | 82 | 79 | 80 |

| 44 | 2. Ability to provide accurate and appropriate information on prescription medicines. | 93 | 92 | 94 | 95 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| 45 | 3. Ability to provide evidence-based support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines. | 90 | 86 | 87 | 81 | 88 | 89 | 87 |

| 17. Patient care competences: monitoring of drug therapy. | 81 | |||||||

| 46 | 1. Ability to identify and prioritise problems in the management of medicines in a timely and effective manner and so ensure patient safety. | 91 | 86 | 95 | 89 | 82 | 85 | 88 |

| 47 | 2. Ability to monitor and report adverse drug events and adverse drug reactions (ADEs and ADRs) to all concerned, in a timely manner, and in accordance with current regulatory guidelines on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVPs). | 83 | 85 | 94 | 87 | 84 | 83 | 86 |

| 48 | 3. Ability to undertake a critical evaluation of prescribed medicines to confirm that current clinical guidelines are appropriately applied. | 78 | 77 | 94 | 74 | 83 | 83 | 82 |

| 49 | 4. Ability to monitor patient care outcomes to optimise treatment in collaboration with the prescriber. | 83 | 78 | 93 | 80 | 85 | 83 | 84 |

| 50 | 5. Ability to contribute to the cost effectiveness of treatment by collection and analysis of data on medicines’ use. | 58 | 59 | 95 | 67 | 69 | 58 | 68 |

References

- The PHAR-QA Project: Quality Assurance in European Pharmacy Education and Training. Available online: http://www.phar-qa.eu (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. The PHAR-QA project: Competency framework for pharmacy practice—First steps, the results of the European network Delphi round 1. Pharmacy 2015, 3, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EU Directive 2013/55/EU on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:255:0022:0142:EN:PDF (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- European Commission. The High Level Group on the Modernisation of Higher Education: Report to the European Commission. 2013. Available online: http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/high-level-group-on-the-modernisation-of-higher-education-pbNC0113156/ (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Landeta, J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PHARMINE (Pharmacy Education in Europe) Consortium. Work Programme 3: Final Report Identifying and Defining Competences for Pharmacists. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PHARMINE-WP3-Final-ReportDEF_LO.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- United Nations Industrial Development Association. Available online: http://www.unido.org/.../16959_DelphiMethod.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- The PHAR-QA Project: Quality Assurance in European Pharmacy Education and Training. Work Package 2 “Implementation”. Available online: http://www.phar-qa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PHAR_QA_WP2_Implementation.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Marz, R.; Dekker, F.W.; van Schravendijk, C.; O’Flynn, S.; Ross, M.T. Tuning research competences for bologna three cycles in medicine: Report of a MEDINE2 European consensus survey. Perpect. Med. Educ. 2013, 2, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leik, R.K. A measure of ordinal consensus. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1966, 9, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualitative Data Systems Analysis. Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR). Available online: http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Smith, A.E.; Humphreys, M.S. Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How to Calculate Sample Size in Surveymonkey®. Available online: https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size/ (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. Does the subject of the pharmacy degree course influence the community pharmacist’s views on competences for practice? Pharmacy 2015, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. How do European pharmacy students rank competences for practice? Pharmacy 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Rombaut, B. The 2011 PHARMINE report on pharmacy and pharmacy education in the European Union. Pharm. Pract. (Granada) 2011, 9, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. What is a pharmacist: Opinions of pharmacy department academics and community pharmacists on competences required for pharmacy practice. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association for Dental Education in Europe. Available online: http://www.adee.org/ (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Antoniou, S.; Webb, D.G.; Mcrobbie, D.; Davies, J.G.; Bates, I.P. A controlled study of the general level framework: Results of the South of England competency study. Pharm. Educ. 2005, 5, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslade, N.E.; Tamblyn, R.M.; Taylor, L.K.; Schuwirth, L.W.T.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Integrating performance assessment, maintenance of competence, and continuing professional development of community pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupans, I.; McAllister, S.; Clifford, R.; Hughes, J.; Krasse, I.; March, G.; Owen, S.; Woulf, J. Nationwide collaborative development of learning outcomes and exemplar standards for Australian pharmacy programmes. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, G.E.P. Non-normality and tests on variances. Biometrika 1953, 40, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramia, E.; Salameh, P.; Btaiche, I.F.; Saa, A.H. Mapping and assessment of personal and professional development skills in a pharmacy curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Phase |

|---|---|

| 1 | A competence framework based on PHARMINE [6] and other published frameworks for practice in healthcare was ranked (4-point Likert scale) and refined by 3 rounds of a Delphi process [7], by a small expert panel consisting of the authors of this paper. |

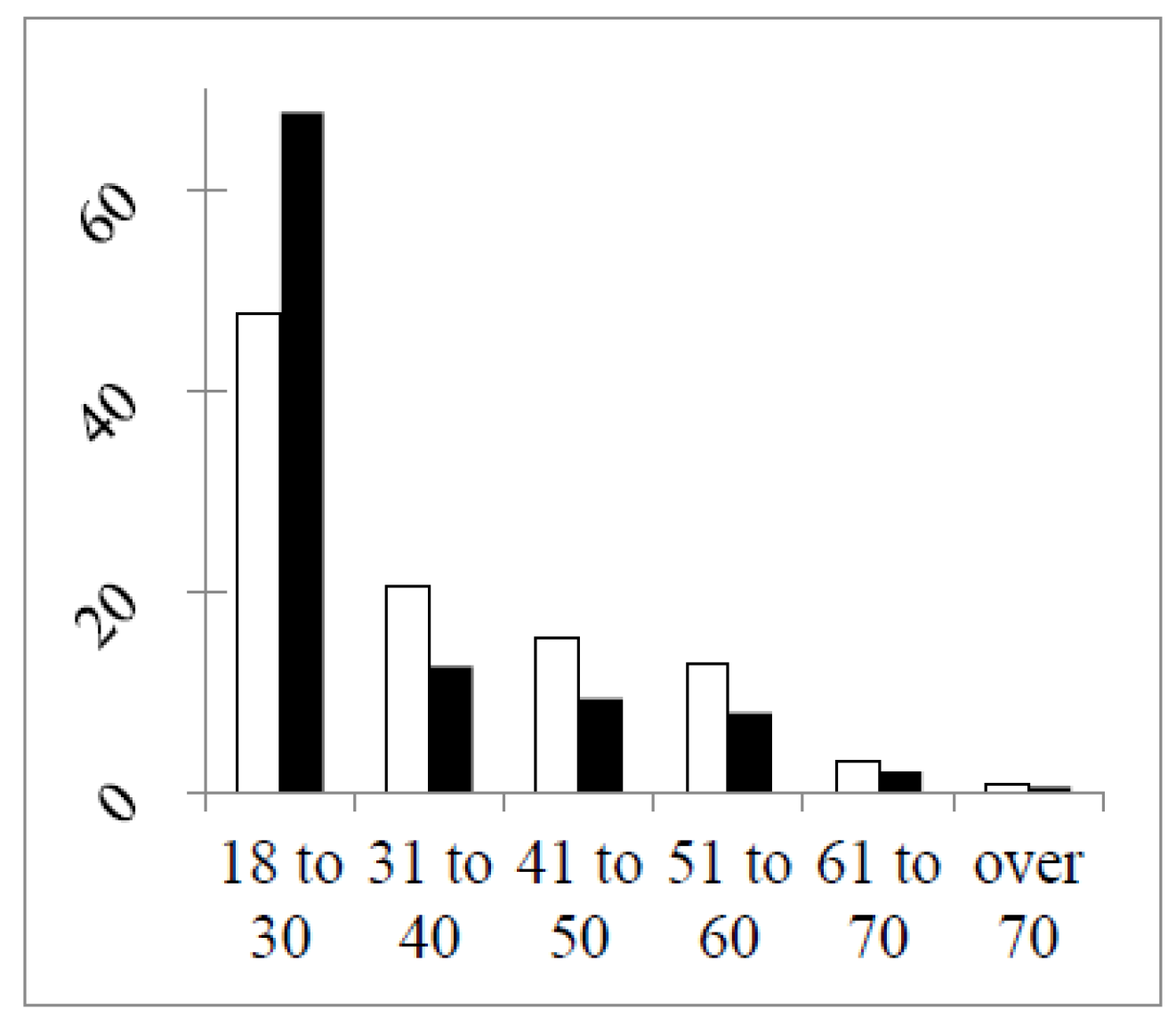

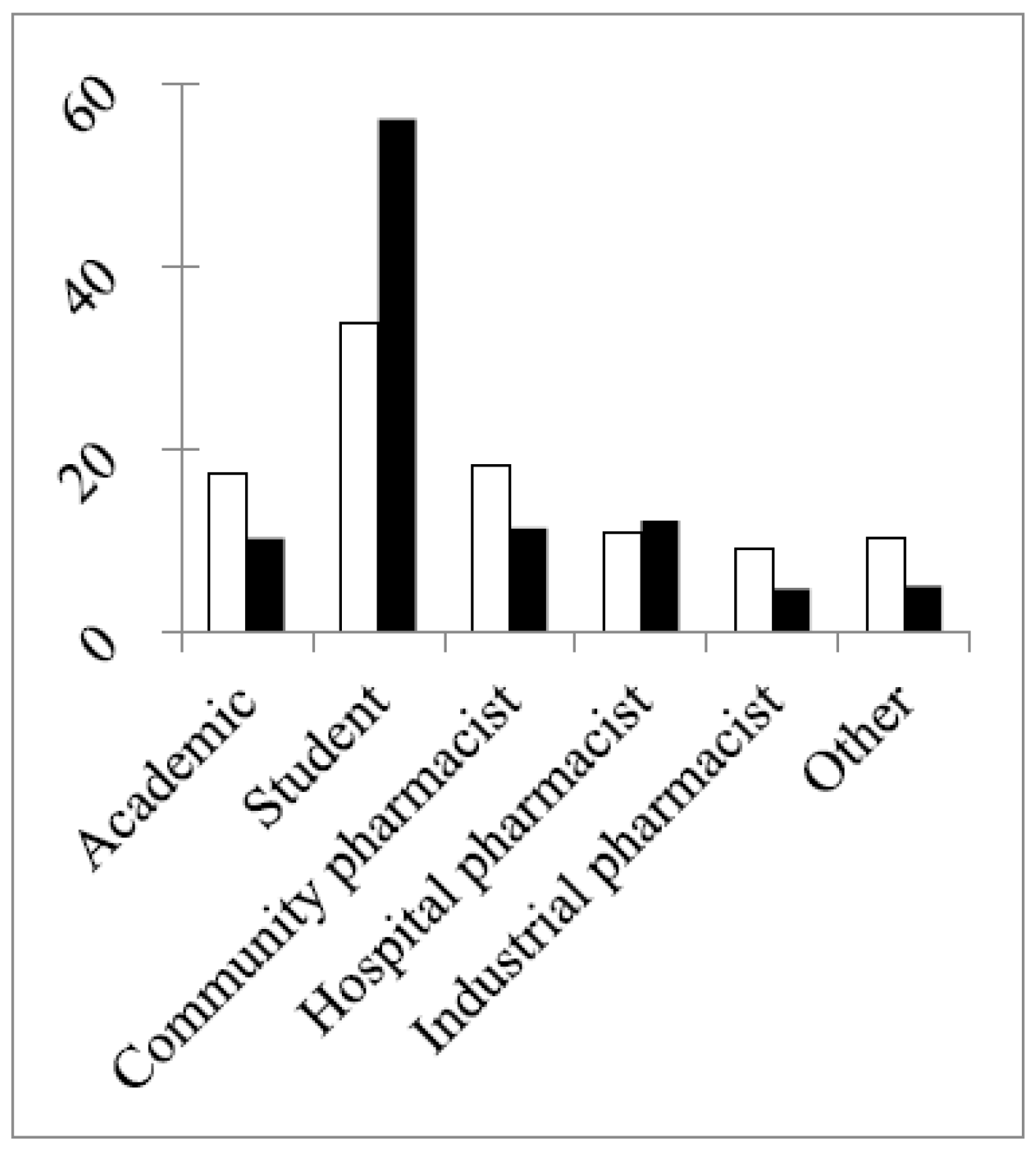

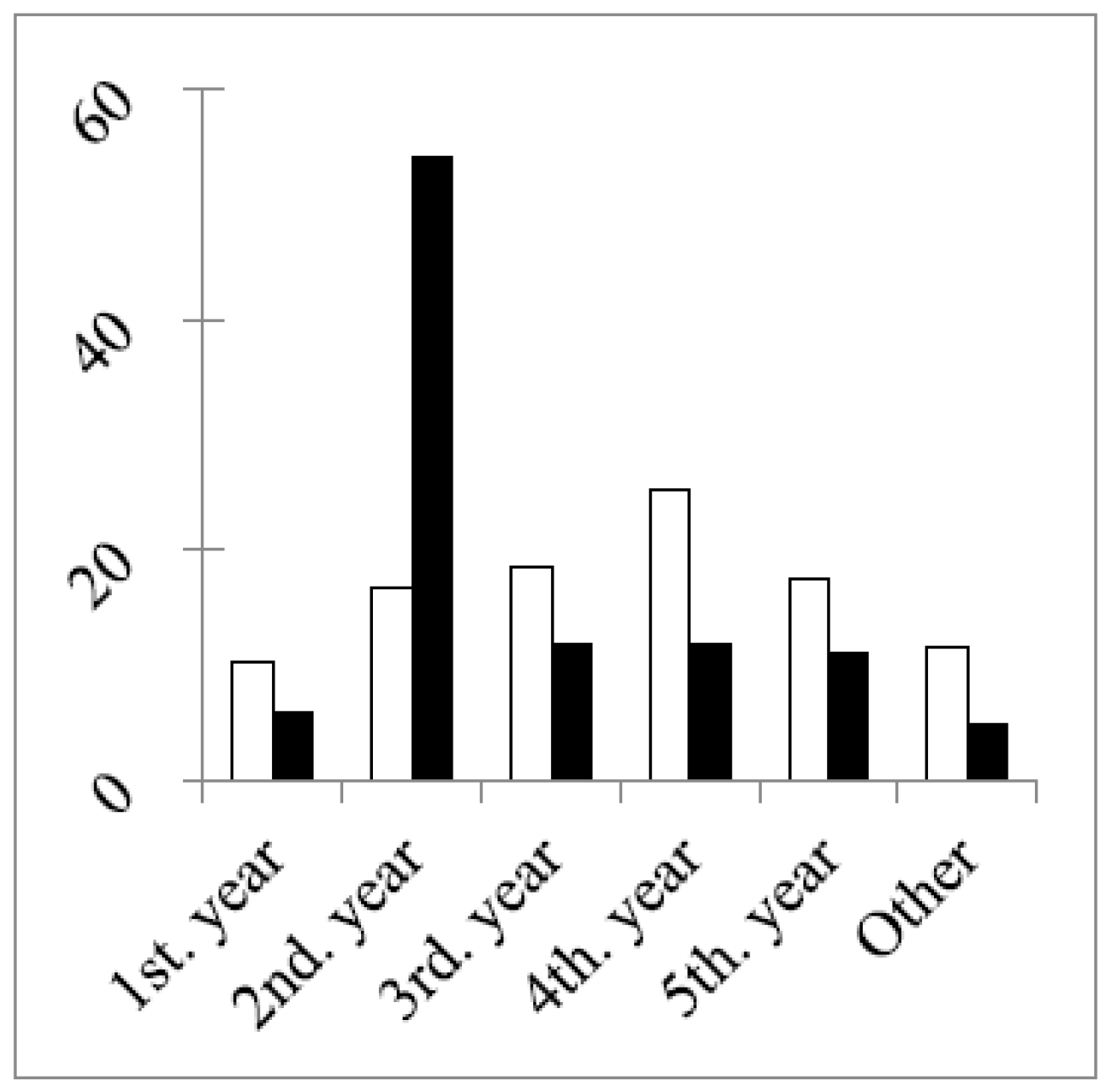

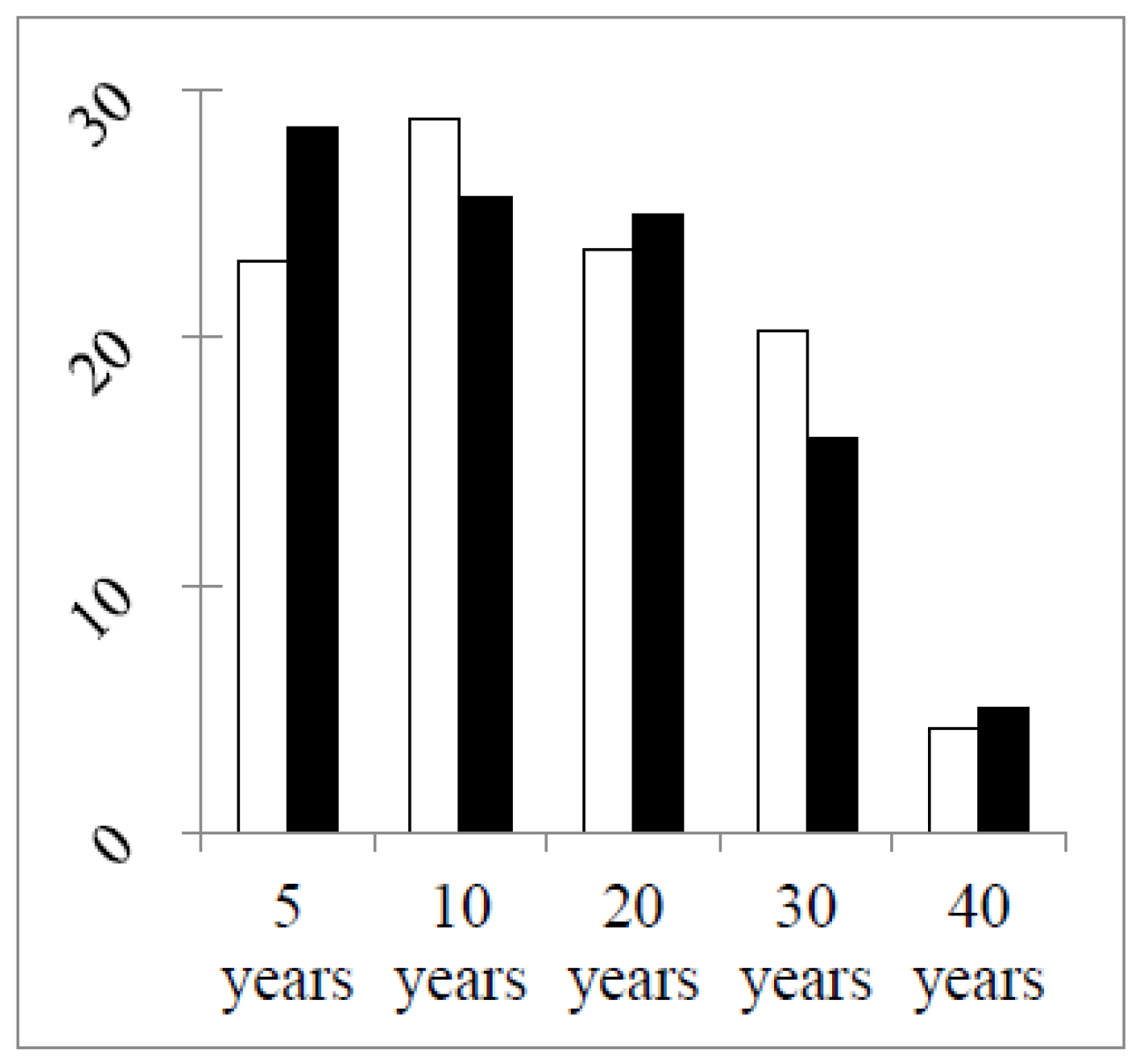

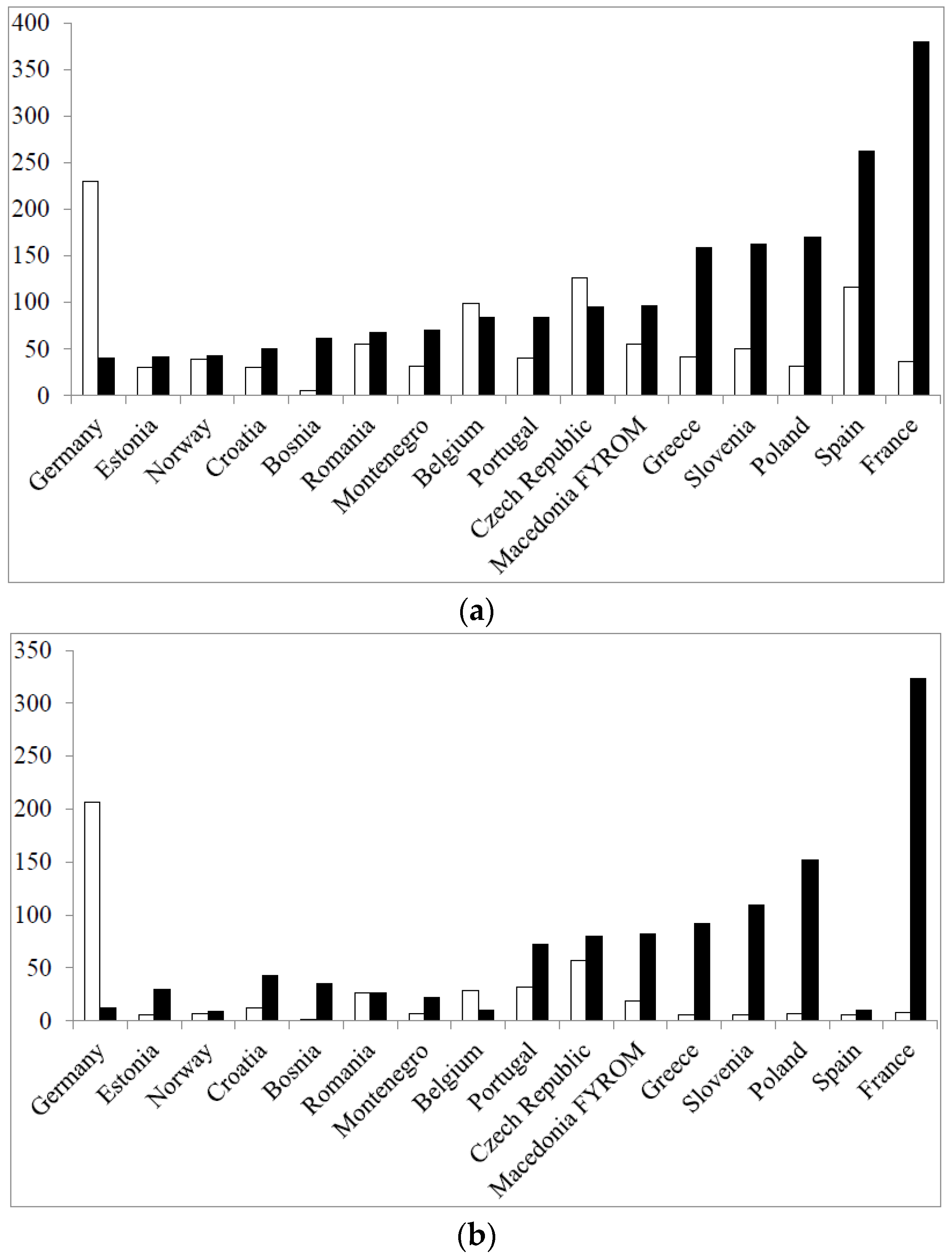

| 2 | Following the 3rd Delphi round within the small expert panel above, the competences were ranked in two separate rounds by a large expert panel consisting of six groups, European academics, students and practicing pharmacists (community, hospital, industrial and pharmacists working in other professions), using the PHAR-QA SurveyMonkey® (SurveyMonkey Company, Palo Alto, CA, USA) questionnaire [8]. There were 68 competences proposed in the first round and 50 in the second, the difference being due primarily to the removal of the subject areas. Invitations were sent to the 43 countries of the European Higher Education Area that have university pharmacy departments (thus excluding countries, such as Luxembourg and the Vatican). Data were obtained from 38 countries (thus not including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Russia). In some figures, not all countries are represented, but data from all countries were included in the statistical analysis. |

| 3 | The first 6 questions were on the profile of the respondent (age, occupation, experience). |

| 4 | Respondents were then asked to rank clusters of questions on competences numbered 7–17 (numbering following on from the 6th question of the respondent profile). Questions in Clusters 7 through 10 were on personal competences and in Clusters 11–17 on patient care competences. |

| 5 | Respondents were asked to rank the proposals for competences on a 4-point Likert scale: |

| (1) Not important = Can be ignored; | |

| (2) Quite important = Valuable, but not obligatory; | |

| (3) Very important = Obligatory, with exceptions depending on the field of pharmacy practice; | |

| (4) Essential = Obligatory. | |

| There was also a “cannot rank” possibility and the possibility of leaving an answer blank. | |

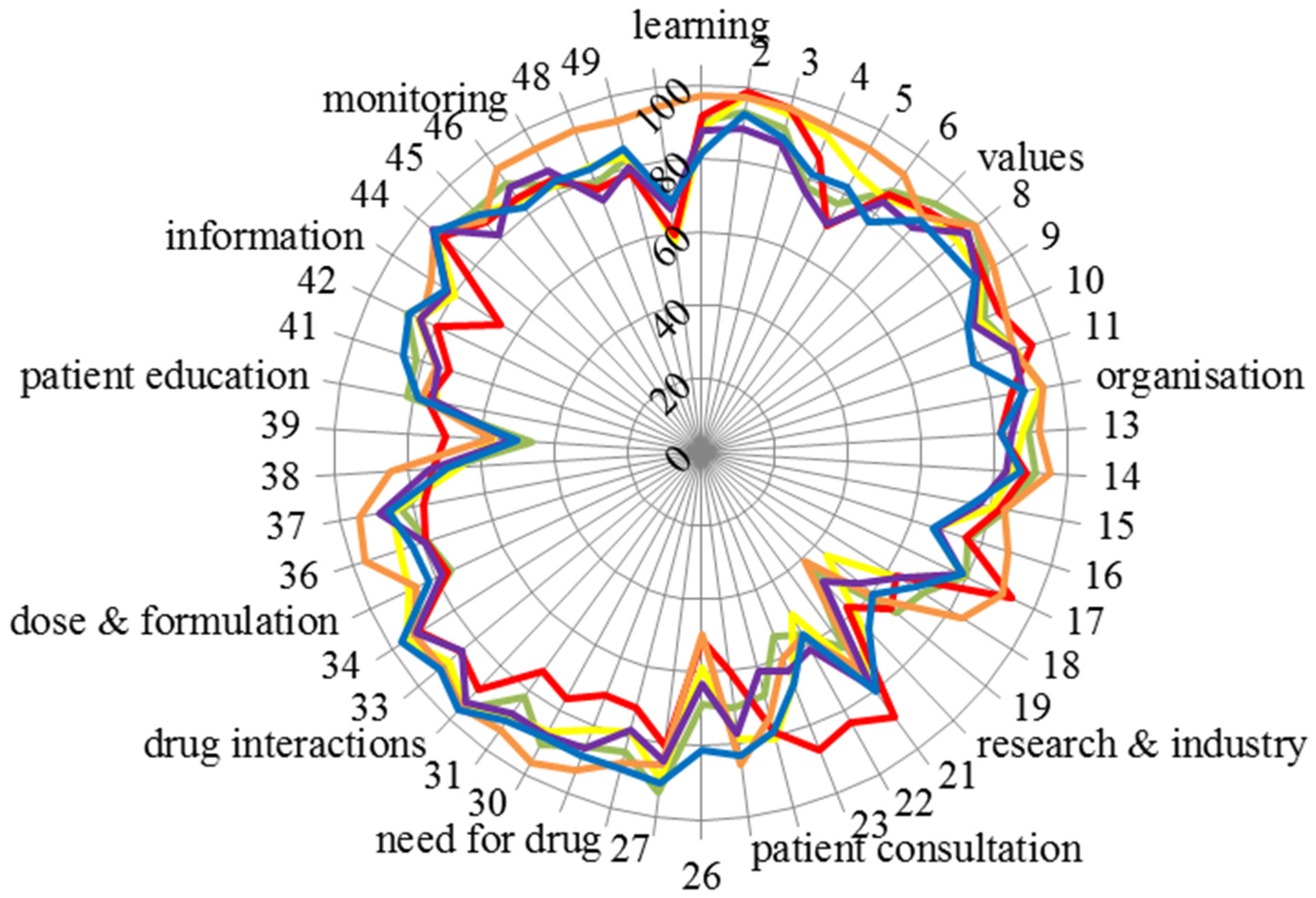

| 6 | Ranking scores were calculated (frequency rank 3 + frequency rank 4) as the % of total frequency; this represents the percentage of respondents that considered a given competence as “obligatory”. |

| The calculation of scores is based on that used by the MEDINE “Medical Education in Europe” study [9]. | |

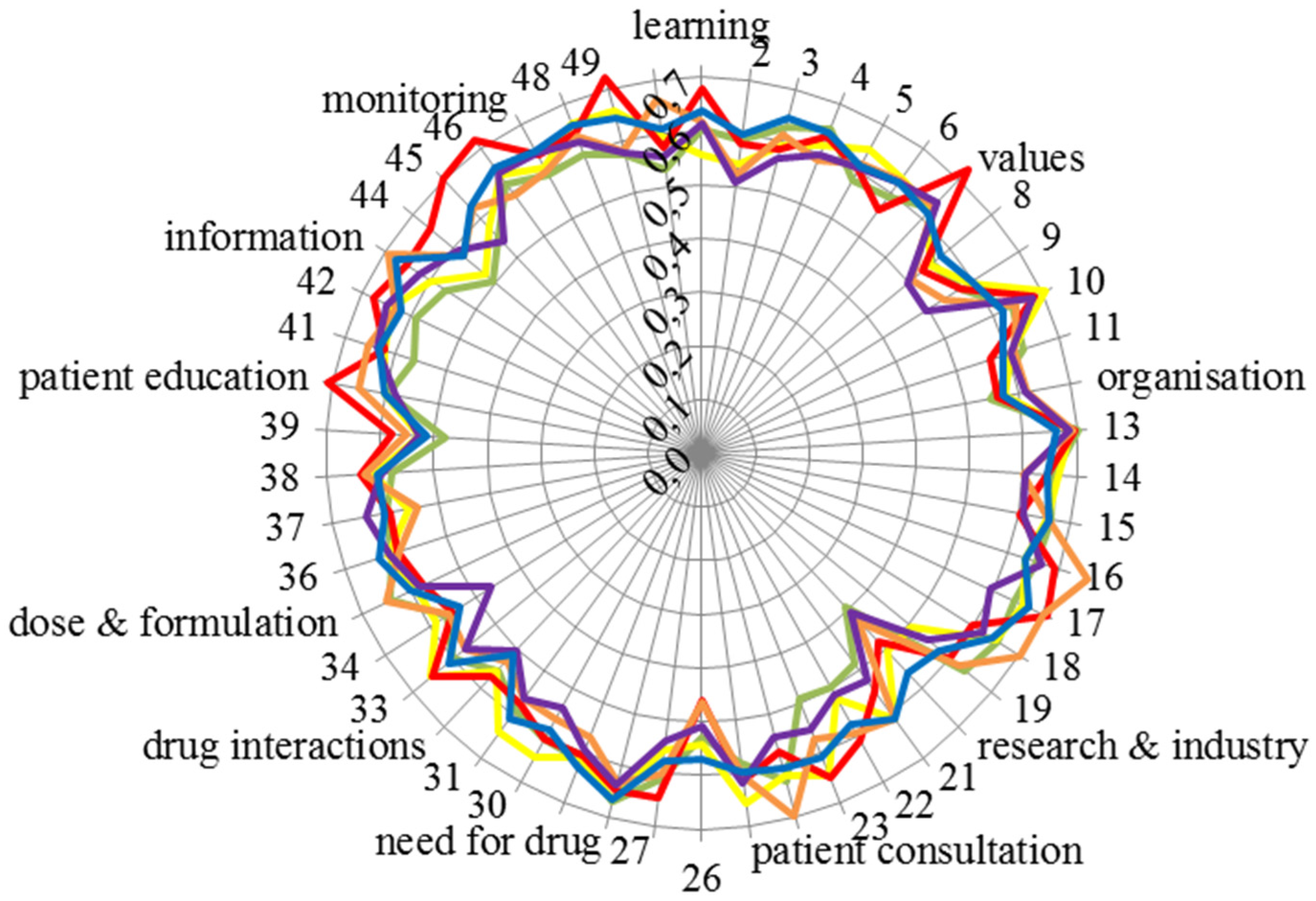

| 7 | Leik ordinal consensus [10] was calculated as an indication of the dispersion of the data within a given group. Responses for consensus were arbitrarily classified as: <0.2 poor, 0.21–0.4 fair, 0.41–0.6 moderate, 0.61–0.8 substantial, >0.81 good, as in the MEDINE study [7]. |

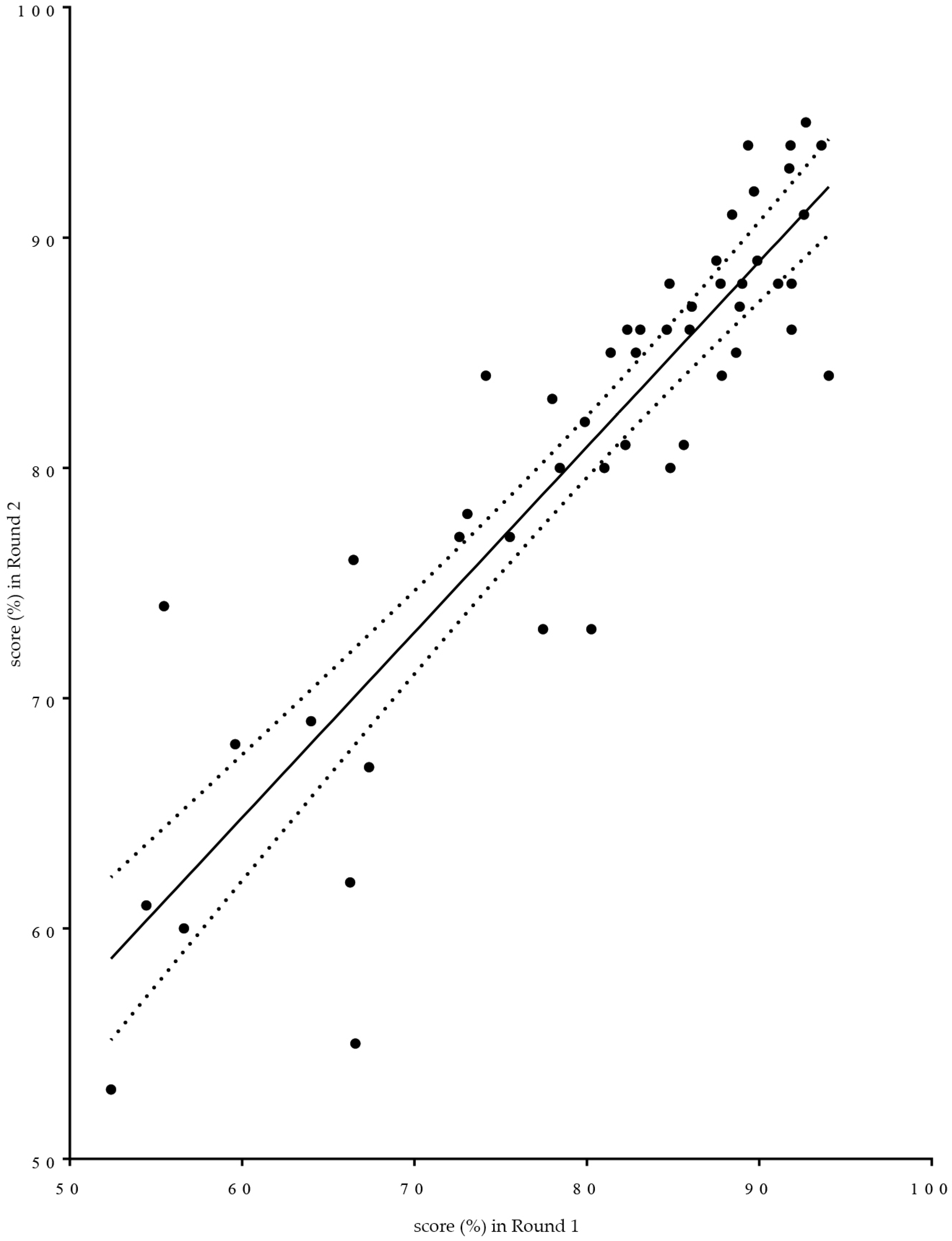

| 8 | For differences amongst groups and amongst competences, the statistical significance of differences was estimated from the chi-square test; a significance level of 5% was chosen. Correlation was estimated from the non-parametric Spearman’s “r” coefficient and graphically represented using parametric linear regression. |

| 9 | Respondents could also comment on their ranking. An attempt was made to analyse comments using the NVivo10® (QSR International Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia) [11] and the Leximancer® (Leximancer Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia) [12] programs for the analysis of semi-quantitative data. In this study and the previous first round study, the word number of the comments was too small to draw significant conclusions. |

| Round 1 | February 2014–November 2014 | Round 2 | August 2015–February 2016 | n of Double Replies ** | Double Replies % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Total Number of Web Entries | Respondents Going beyond Question 6 * | % Respondents Going beyond Question 6 | Total Number of Web Entries | Respondents Going beyond Question 6 * | % Respondents Going beyond Question 6 | ||

| Community pharmacists | 285 | 258 | 91 | 264 | 183 | 69 | 16 | 9 |

| Industrial pharmacists | 140 | 135 | 97 | 109 | 93 | 85 | 15 | 16 |

| Hospital pharmacists | 173 | 152 | 88 | 271 | 188 | 69 | 29 | 15 |

| Pharmacists in other professions | 159 | 77 | 48 | 89 | 72 | 81 | 4 | 5 |

| Students | 529 | 382 | 72 | 1250 | 785 | 63 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Academics | 267 | 241 | 90 | 235 | 207 | 88 | 21 | 10 |

| Total | 1553 | 1245 | NA | 2218 | 1528 | NA | NA | NA |

| Average | NA | NA | 80 | NA | NA | 69 | NA | 9 |

| Group | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Community pharmacists | 0.24 | p < 0.05 |

| Hospital pharmacists | 0.68 | p < 0.05 |

| Industrial pharmacists | 0.15 | p < 0.05 |

| Pharmacists in other professions | 0.00002 | NS |

| Academics | 0.02 | NS |

| Students | 0.0007 | NS |

| Ranking | Number of Rankings | % |

|---|---|---|

| Essential | 25,426 | 33.3 |

| Very important | 27,959 | 36.6 |

| Quite important | 10,708 | 14.0 |

| Not important | 1240 | 1.6 |

| Cannot rank | 1909 | 2.5 |

| Subtotal | 67,242 | 88.0 |

| Blanks | 9158 | 12.0 |

| Total | 1528 × 50 = 76,400 | 100.0 |

| Group | Number of Respondents | Number of Commentators | % Respondents Commenting | Number of Comments | Number of Comments/Commentator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community pharmacists | 183 | 6 | 3.3 | 19 | 3.17 |

| Hospital pharmacists | 188 | 8 | 4.3 | 13 | 1.63 |

| Industrial pharmacists | 93 | 3 | 3.2 | 13 | 4.33 |

| Pharmacists working in other professions | 72 | 6 | 8.3 | 8 | 1.33 |

| Students | 785 | 16 | 2.0 | 33 | 2.06 |

| Academics | 207 | 11 | 5.3 | 27 | 2.45 |

| Total | 1528 | 50 | 3.3 | 113 | 2.26 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atkinson, J.; De Paepe, K.; Pozo, A.S.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. The Second Round of the PHAR-QA Survey of Competences for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030027

Atkinson J, De Paepe K, Pozo AS, Rekkas D, Volmer D, Hirvonen J, Bozic B, Skowron A, Mircioiu C, Marcincal A, et al. The Second Round of the PHAR-QA Survey of Competences for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy. 2016; 4(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtkinson, Jeffrey, Kristien De Paepe, Antonio Sánchez Pozo, Dimitrios Rekkas, Daisy Volmer, Jouni Hirvonen, Borut Bozic, Agnieska Skowron, Constantin Mircioiu, Annie Marcincal, and et al. 2016. "The Second Round of the PHAR-QA Survey of Competences for Pharmacy Practice" Pharmacy 4, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030027

APA StyleAtkinson, J., De Paepe, K., Pozo, A. S., Rekkas, D., Volmer, D., Hirvonen, J., Bozic, B., Skowron, A., Mircioiu, C., Marcincal, A., Koster, A., Wilson, K., & Van Schravendijk, C. (2016). The Second Round of the PHAR-QA Survey of Competences for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy, 4(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030027