Factors Influencing Successful Prescribing by Intern Doctors: A Qualitative Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

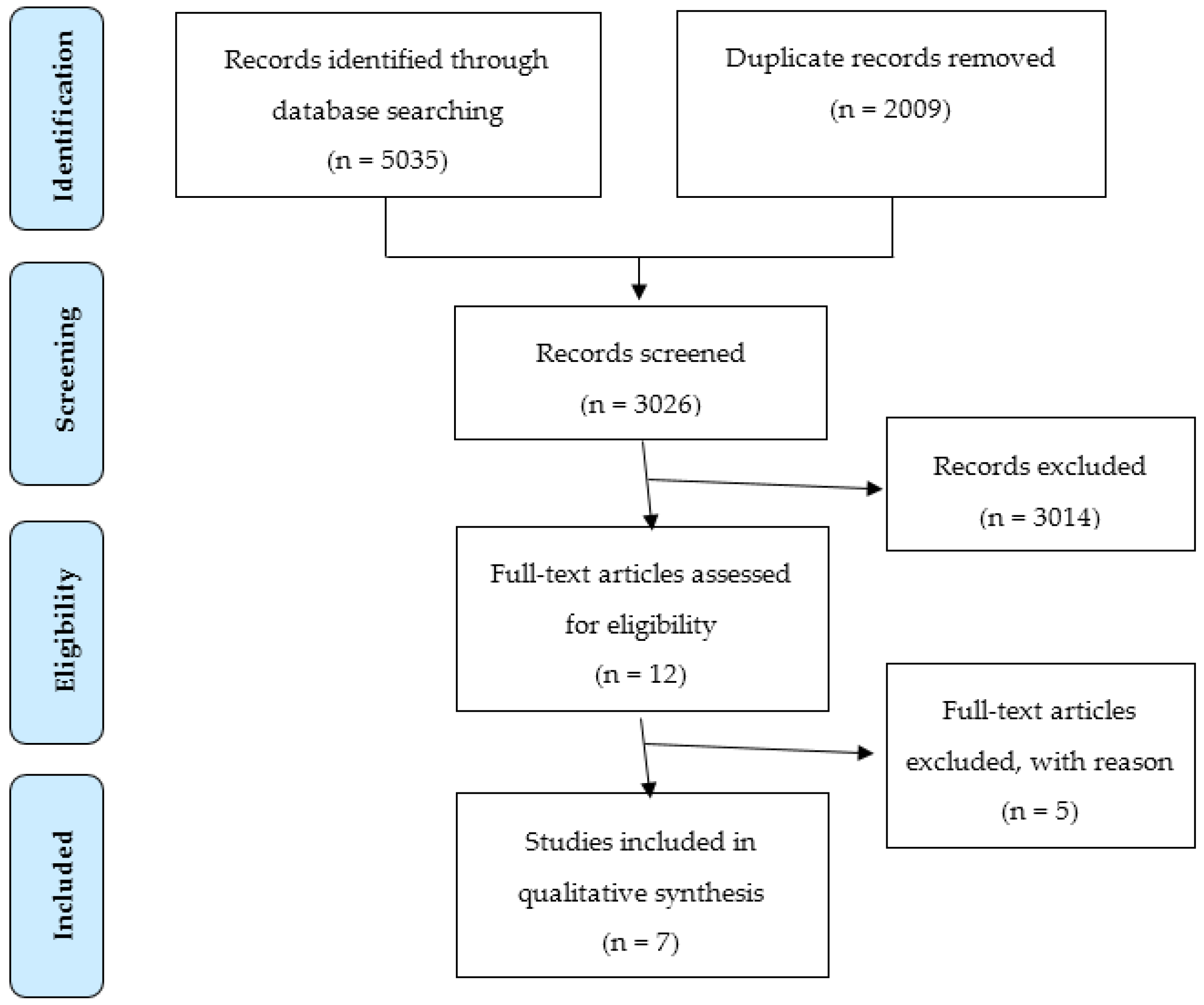

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Taxonomy

3.3. Definition of an Error

“a clinically meaningful prescribing error occurs when, as a result of a prescribing decision or prescription writing process, there is an unintentional significant (1) reduction in the probability of treatment being timely and effective or (2) increase in the risk of harm when compared with generally accepted practice.”

3.4. Theoretical Approach

3.5. Factors Influencing Prescribing Behaviour

3.5.1. Environmental Factors

3.5.2. Patient Factors

3.5.3. Individual Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. The Findings

4.2. Implications for Practice

- Supervision of the intern doctors by a team which constitutes other healthcare professionals, i.e., pharmacists and nursing staff, which provides the interns with information to prescribe and gives them real time feedback on inappropriate prescribing behaviour and prescribing errors.

- Introduction to prescribing in hospital, on specific wards or specialities, including the introduction to specific treatment guidelines, drug chart layout and location and use of information sources.

4.3. Risk of Bias

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| TITLE | Reported on Page: | ||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 3 (Supplementary) |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 3–4 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 3–4 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Supplementary |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 4 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 4 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | - |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | - |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2) for each meta-analysis. | - |

References

- Heaton, A.; Webb, D.J.; Maxwell, S.R. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: The views of 2413 uk medical students and recent graduates. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 66, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.; McLay, J.S.; Ross, S.; Davey, P.; Duncan, E.M.; Ker, J.; Lee, A.J.; MacLeod, M.J.; Maxwell, S.; McKay, G.A.; et al. Prevalence and causes of prescribing errors: The prescribing outcomes for trainee doctors engaged in clinical training (protect) study. Figshare 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornan, T.; Ashcroft, D.A.; Heathfield, H.; Lewis, P.; Taylor, D.; Tully, M.; Wass, V. An in Depth Investigation into Causes of Prescribing Errors by Foundation Trainees in Relation to Their Medical Education Equip Study; Hope Hospital and University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2008; pp. 1–215. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, E.; Michaelsen, M.; Bradley, C.; McCague, P.; Coakley, S.; Owens, R.; Sahm, L.J. Prescribing error at the primary-secondary care interface: An audit of hospital discharge prescriptions. In Prescribing and Research in Medicines Management (UK & Ireland); PDS: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, T.; Deasy, E.; Allen, A.; O’Byrne, J.; Delaney, T.; Barragry, J.; Breslin, N.; Moloney, E.; Wall, C. Collaborative pharmaceutical care in an irish hospital: Uncontrolled before-after study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, T.; Delaney, T.; Duggan, C.; Kelly, J.G.; Graham, I.M. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharge: Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 177, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopotowska, J.E.; Kuiper, R.; van Kan Hendrikus, J.; de Pont, A.C.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Lie-A-Huen, L.; Vroom, M.B.; Smorenburg, S.M. On-ward participation of a hospital pharmacist in a dutch intensive care unit reduces prescribing errors and related patient harm: An intervention study. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asking Focused Questions. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/asking-focused-questions/ (accessed on 19 August 2016).

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 3rd ed.; Silverman, D., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–321. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Available online: http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 (accessed on 19 August 2016).

- Appendix 12: Data Extraction Forms for Qualitative Studies. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42/evidence/guidance-appendix-12-195023346 (accessed on 19 August 2016).

- Ross, S.; Ryan, C.; Duncan, E.M.; Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Ker, J.S.; Lee, A.J.; MacLeod, M.J.; Maxwell, S.; McKay, G.; et al. Perceived causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors in hospital inpatients: A study from the protect programme. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.M.; Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Davey, P.; Maxwell, S.; McKay, G.A.; McLay, J.; Ross, S.; Ryan, C.; Webb, D.J.; et al. Learning curves, taking instructions, and patient safety: Using a theoretical domains framework in an interview study to investigate prescribing errors among trainee doctors. Implement. Sci. IS 2012, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, I.D.; Stowasser, D.A.; Coombes, J.A.; Mitchell, C. Why do interns make prescribing errors? A qualitative study. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearson, S.; Rolfe, I.; Smith, T. Factors influencing prescribing: An intern’s perspective. Med. Educ. 2002, 36, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.; Catchpole, K.; Baker, P. Human factors perspective on the prescribing behavior of recent medical graduates: Implications for educators. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2013, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, B.; Schachter, M.; Vincent, C.; Barber, N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: A prospective study. Lancet 2002, 359, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.J.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Dornan, T.; Taylor, D.; Wass, V.; Tully, M.P. Exploring the causes of junior doctors’ prescribing mistakes: A qualitative study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, B.; Barber, N.; Schachter, M. What is a prescribing error? Qual. Health Care 2000, 9, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carayon, P.; Schoofs Hundt, A.; Karsh, B.T.; Gurses, A.P.; Alvarado, C.J.; Smith, M.; Flatley Brennan, P. Work system design for patient safety: The seips model. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, i50–i58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webbe, D.; Dhillon, S.; Roberts, C.M. Improving junior doctor prescribing—The positive impact of a pharmacist intervention. Pharm. J. 2007, 278, 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dudovskiy, J. Research Methodology. Available online: http://research-methodology.net/sampling/convenience-sampling/ (accessed on 19 August 2016).

| Reason | Point of Exclusion a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Abstract | Full-Text | |

| Not relevant to prescribing behaviour among intern doctors | 2840 | 43 | 2 |

| Literature reviews, meta-analyses | 19 | 8 | 0 |

| Surveys, questionnaires, observational studies, case studies | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Commentaries, editorials, conference material, abstracts only | 40 | 24 | 1 |

| Data restricted to intern doctors unavailable | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Study | Study Aims | Theory a | Setting | Sampling | Participants b | Data Collection | Definition of Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gordon et al. [16], 2013 | To investigate factors which impact graduates prescribing | SEIPS | UK c, Medical school (n = 1) | Not specified | FY1, FY2 (n = 11) | Semi-structured interviews | Not specified |

| Duncan et al. [13], 2010–2011 | Use the TDF to investigate prescribing among trainee doctors in the hospital setting | TDF | Scotland, Hospital (n = 11) | Purposive | FY1, FY2 (n = 22) | Semi-structured interview | Dean et al. [19] |

| Ross et al. [12], 2010–2011 | To investigate perceived causes of prescribing errors | Reason | Scotland, Hospital (n = 9) | Not specified | FY1, FY2 (n = 40) | Semi-structured interviews | Dean et al. [19] |

| Coombes et al. [14], 2004 | To identify factors underlying prescribing errors made by interns | Reason | Australia, Hospital (n = 1) | Not specified | Interns (n = 14) | Semi-structured interviews | Dean et al. [19] |

| Dean et al. [17], 2002 | To use the theories of human errors to investigate causes of prescribing errors | Reason | UK c, Hospital (n = 1) | Conv. d | All medical staff (n = 41) | Semi-structured interviews | Dean et al. [19] |

| Lewis et al. [18], 2008 | To explore the causes of prescribing errors by foundation doctors | Reason | England, Hospital (n = 17), Medical school (n = 18) | Purposive | FY1 (n = 30) | In-depth interviews | Dean et al. [19] |

| Pearson et al. [15], 2002 | To examine influences on intern prescribing practice | Not specified | Australia, Hospital (n = 2) | Random | Interns (n = 10) | Semi-structured interviews | Not specified |

| Theme | Subtheme | Synopsis |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Time constraints | Interns report being “rushed”, especially on overtime shifts and night duty. In order to “survive” interns are “constantly thinking of time-saving manoeuvres”. Interns believe that there is often “a conflict between managing time and appropriate patient care” [15]. |

| Poor communication | Absence of or poor communication within and between teams contributed to errors. Causes included inability to read handwriting, not documenting drug allergies onto drug charts, inept crossing off of drugs, absence of documentation in the patient’s notes of the prescribed drug and justification for its use, and removal of drug charts from the wards [17]. | |

| Defences | Nurses were perceived to be good at identifying errors before they reached the patient and were reported as sharing responsibility for ensuring that prescribing errors did not reach patients. Similarly, pharmacists were also believed to check prescriptions and identify prescribing errors [13]. “... I know someone else is going to check it, whether it’s the pharmacist or whether, I know that somebody will go through it the next morning and confirm ...” (Foundation doctor) [12]. | |

| Hierarchical structures | Steep hierarchical structures within medical teams prevented doctors from seeking help or indeed receiving adequate help, highlighting the importance of the prevailing medical culture [14]. Interns perceive that they “sit at the bottom of the hospital hierarchy” and as such need to “fall into line” with senior medical and nursing staff: “there is a difference between good prescribing intentions and what you actually do—you have to fit in with the system” (Intern doctor) [15]. | |

| Rotation | Rotation between wards and medical teams were perceived a challenge: “So every time you move onto the next job, you’ve got to sit back and try and work out how they do, how they do it here, you know what sort of sheet you’re supposed to prescribe it on and that becomes confusing.” (Foundation Year 2 doctor) [13]. | |

| Individual | Wellbeing | Staffing numbers and expected patient throughput affected workloads, which led to mental and physical fatigue, stress and distraction [14]. |

| Knowledge | The type of knowledge that the doctors’ lacked was often practical knowledge of how to prescribe, rather than pharmacological knowledge. For example, doctors reported a deficiency in their knowledge of dosage, duration of antibiotic treatment and legal requirements of opioid prescriptions. Most doctors discussed how they were aware of their lack of knowledge at the time of prescribing [18]. | |

| Attitude and awareness | Re-prescribing was commonly mentioned as requiring little thought and of low risk or importance [14]. Although interviewees were cognizant of the potential consequences of prescribing errors, they did not discuss these beliefs as explicitly influencing their behaviour [13]. However, some participants clearly exhibited heightened awareness of error, from their own experience and observations and reflected on their negative behaviour to improve their practice [16]. | |

| Responsibility | Senior colleagues were often reported to be the group making the prescribing decisions, with the prescription writing being done by the trainee doctors. Despite this, participants reported that by signing the prescription, they were taking responsibility for it [13]. Some junior doctors were unclear whose responsibility prescription of drugs was in such instances, and felt that if there was a problem, responsibility would rest with the senior doctor [17]. | |

| Experience | Less-experienced doctors were considered to be inherently more likely to make an error but were also more likely to check information sources to verify their prescribing [13]. | |

| Patient | Complexity | The most frequent patient factor mentioned was the complexity or acuity of the case [14]. |

| Poor communication | Poor information from patients was also noted including inability to communicate because of language difficulty, sedation or a neurosurgical complication [12,14]. | |

| Patients’ influence | Also discussed was the influence of patients and patients’ relatives on prescribing, with some reports that patient may influence drug choice or dosage. However, many of the participants reported that patients’ views may not always be taken into account when prescribing [13]. |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

R. Hansen, C.; Bradley, C.P.; Sahm, L.J. Factors Influencing Successful Prescribing by Intern Doctors: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030024

R. Hansen C, Bradley CP, Sahm LJ. Factors Influencing Successful Prescribing by Intern Doctors: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Pharmacy. 2016; 4(3):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleR. Hansen, Christina, Colin P. Bradley, and Laura J. Sahm. 2016. "Factors Influencing Successful Prescribing by Intern Doctors: A Qualitative Systematic Review" Pharmacy 4, no. 3: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030024

APA StyleR. Hansen, C., Bradley, C. P., & Sahm, L. J. (2016). Factors Influencing Successful Prescribing by Intern Doctors: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Pharmacy, 4(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4030024