Restrictions to Pharmacy Ownership and Vertical Integration in Estonia—Perception of Different Stakeholders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- ownership—limited to the pharmacy profession, limited number of pharmacies (horizontal integration), limited to prescribers, manufacturers, and wholesalers (vertical integration);

- -

- demographic and geographic restrictions for opening a new pharmacy;

- -

- pharmacy monopoly for sale of prescription and (non-prescription) medicines;

- -

- standard requirements for marketing authorization of medicines;

- -

2. Objectives

3. Methods

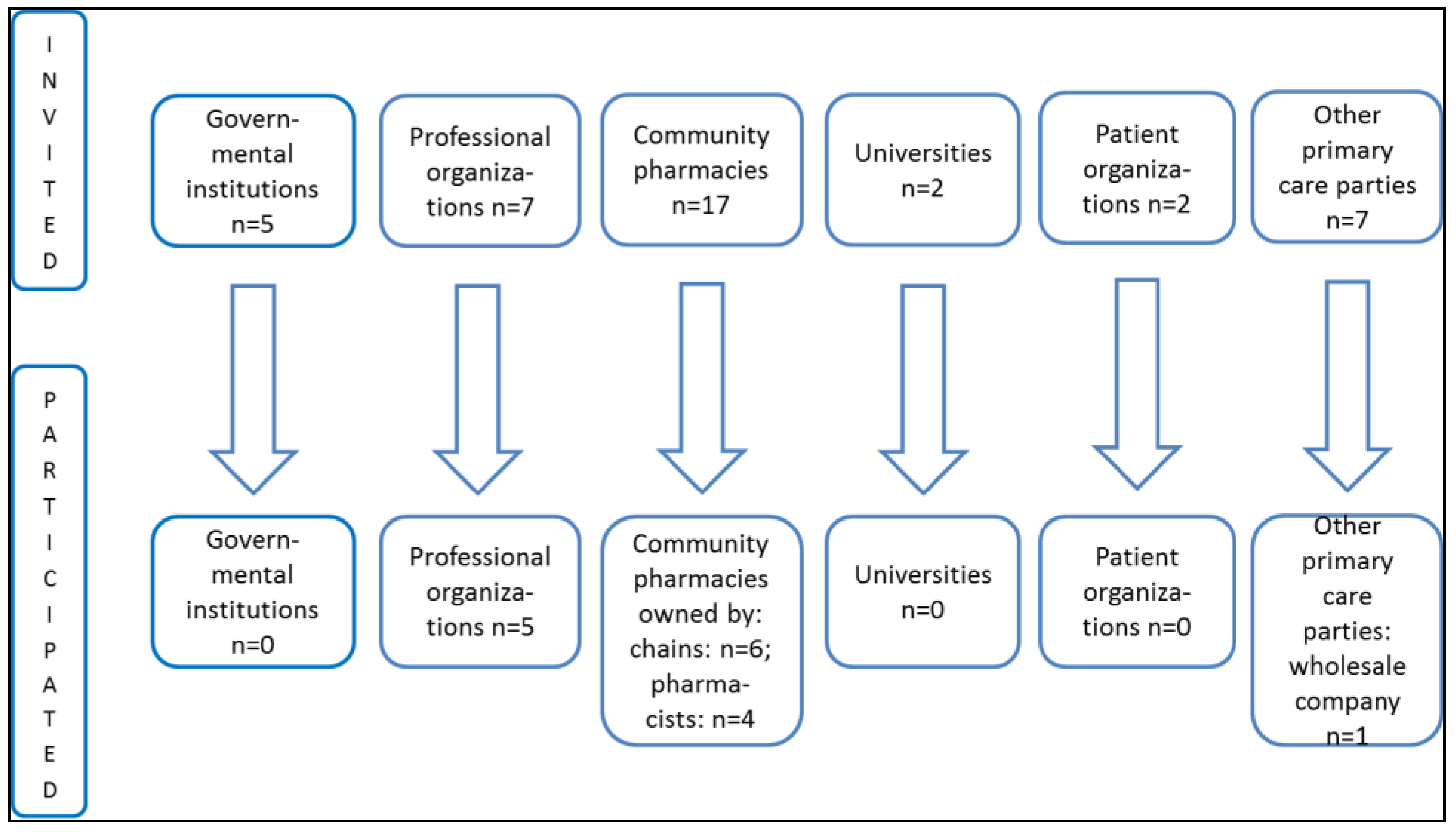

3.1. Study Design and Sample

3.2. Survey Instrument

- (1)

- How could the transition of pharmacy ownership be organized to satisfy all parties involved? Should the government provide financial support to pharmacists who want to open or buy a pharmacy?

- (2)

- What impact could the prohibition of vertical integration have on the pharmacy sector?

- (3)

- Will the new regulation increase or decrease competition in the community pharmacy sector? Will new companies enter the pharmaceutical wholesale market after the prohibition of vertical integration?

- (4)

- Will the new regulation increase or decrease the number of community pharmacies? How will the situation change for community pharmacies in rural areas?

- (5)

- Will the new regulation change the quality of community pharmacy services? Should community pharmacy services be classified as healthcare services?

- (6)

- Will the pricing of medicines and wages for community pharmacy professional staff change with the new regulation?

- (7)

- Will the professional roles and responsibilities of a pharmacist and an assistant pharmacist change with the new regulation?

- (8)

- Should pharmacy education be updated according to the new regulation?

3.3. Data Analysis

- (1)

- total impression—researcher reads the entire description or all results to get a general understanding about the topic;

- (2)

- identifying and sorting meaning units—the researcher identifies and organizes the data by meaning units that are related to the study question;

- (3)

- condensation—the researcher examines meaning units one by one to get a detailed understanding of the content of every unit; the data is decontextualized;

- (4)

- synthesizing—the researcher condenses information received from meaning units into a consistent statement/results, and the data is put back into context [13].

4. Results

4.1. Community Pharmacy Service as a Healthcare Service

4.2. The Impact of New Regulations

5. Discussion

Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lluch, M. Are regulations of community pharmacies in Europe questioning our pro-competitive policies? Eurohealth 2009, 15, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, S. Liberalization in the pharmacy sector. In Competition Issues in the Distribution of Pharmaceuticals, Proceedings of Session III of the Global Forum on Competition, Paris, France, 27–28 February 2014; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF%282014%296&docLanguage=En (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Volkerink, B.; de Bas, P.; van Gorp, N.; Philipsen, N. Study of regulatory restrictions in the field of pharmacies. Main Report, ECORYS Nederland BV, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/services/docs/pharmacy/report_en.pdf (accessed 21 October 2015).

- OECD. Competition Issues in the Distribution of Pharmaceuticals (Contribution from Finland). In Proceedings of Session III of the Global Forum on Competition, Paris, France, 27–28 February 2014; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF/WD%282014%2935&docLanguage=En (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Lluch, M.; Kanavos, P. Impact of regulation of community pharmacies on efficiency, access and equity. Evidence from the UK and Spain. Health Policy 2010, 95, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, T.; Habicht, T.; Kahur, K.; Reinap, M.; Kiivet, R.; van Ginneken, E. Estonia: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2013, 15, 1–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medicinal Products Act. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/503092015003/consolide (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Health Insurance Act. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/503082015009/consolide (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Volmer, D.; Bell, J.S.; Janno, R.; Raal, A.; Hamilton, D.D.; Airaksinen, M.S. Change in public satisfaction with community pharmacy services in Tartu, Estonia, between 1993 and 2005. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2009, 5, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Competition issues in the distribution of pharmaceuticals (Contribution from Estonia). In Proceedings of Session III of the Global Forum on Competition, Paris, France, 27–28 February 2014; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF/WD%282014%299&docLanguage=En (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- State Agency of Medicines. Overview of the Activities of Estonian Pharmacies. 2015. Available online: http://www.sam.ee/sites/default/files/Review%20of%20activities%20of%20Estonian%20pharmacies_2014.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Health Services Organization Act. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/505032015002/consolide (accessed on 21 October 2015).

- Malterud, K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Competition issues in the distribution of pharmaceuticals. In Proceedings of Session III of the Global Forum on Competition, Paris, France, 27–28 February 2014; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF/WD%282014%2932&docLanguage=En (accessed on 14 October 2015).

- Wisell, K.; Winblad, U.; Sporrong, S.K. Reregulation of the Swedish pharmacy sector—A qualitative content analysis of the political rationale. Health Policy 2015, 119, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volmer, D.; Vendla, K.; Vetka, A.; Bell, J.S.; Hamilton, D. Pharmaceutical Care in Community Pharmacies: Practice and Research in Estonia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2008, 42, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estonia Pharmaceutical Country Profile. Published by the Ministry of Social Affairs in Collaboration with the World Health Organization. 2011. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/coordination/estonia_pharmaceutical_profile.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2015).

- Eversheds. Restrictions on Pharmacy Ownership in Hungary and the EU’s Recent Challenge against Them. 11 February 2015. Available online: http://www.eversheds.com/global/en/what/articles/index.page?ArticleID=en/Healthcare/Restrictions_on_pharmacy_ownership_in_Hungary_Feb2015 (accessed on 12 March 2016).

- Keero, A.; Viidalepp, A.; Volmer, D.; Monvelt, H.; Kask, H.; Sarv, K.; Alamaa-Aas, K.; Sepp, K.; Saava, L.; Markov, M.; et al. Quality Standards of Community Pharmacy Services; Estonian Pharmacies Association: Tallinn, Estonia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Reform Description |

|---|---|

| 1991–1998 | Privatization of community pharmacies; ownership of community pharmacies not restricted to pharmacists. Emergence of the first pharmacy chains connected to wholesale companies. |

| 1996 | Enactment of Medicinal Products Act, requirement to inform patients about the safe and appropriate use of medicines. |

| 2002–2003 | Development of main principles of pharmaceutical policy. Organization of Department of Medicines at the Ministry of Social Affairs. Introduction of generic prescribing. |

| 2004 | Estonia joined the European Union (EU). |

| 2005–2006 | Revision of the Medicinal Products Act to include a more detailed description of community pharmacy services. Introduction of geographic-demographic restrictions on the opening of new pharmacies. |

| 2009 | Introduction of digital prescriptions. Introduction of EU prescriptions. |

| 2013 | Opening of the first internet pharmacy. Repeal of establishment criteria for community pharmacies. |

| 2014 | Vertical integration restrictions, with a transition period of five years. Pharmacists became healthcare professionals. |

| 2015 | Measures undertaken to improve accessibility to medicines in rural areas: mobile pharmacy, grants for recently graduated specialists, requirement for pharmacy chains to open community pharmacies in rural areas if needed. Ownership restrictions for community pharmacies limited by the pharmacy profession, with a transition period of five years. Horizontal integration restrictions of up to four pharmacies, with a transition period of five years. |

| Restrictions to Ownership of Community Pharmacies and Vertical Integration | |

|---|---|

| Positive Impact | Negative Impact |

| Pharmacist will be independent and able to make professional decisions not related to commercial interests. | Concerns about the sustainable development of community pharmacies as vertical integration helps to support non-profitable operation of retail sale of medicines. |

| A smaller number of pharmacies in towns means existing pharmacies will grow bigger, have more qualified staff, a larger selection of medicines and services. | Closing community pharmacies in rural regions could be seen as an imminent factor reducing accessibility to medicines. |

| Decrease in the prices of medicines due to the elimination of vertical integration, and the market opening to new wholesale companies. | Increase in medicine prices due to the restrictions on vertical integration that currently offers several discounts. |

| Community pharmacies can focus on the development of quality and patient-centered services. | Limited finances to educate pharmacists and invest in the development of community pharmacies. Community pharmacies might concentrate only on medicines and less on extended services. |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gross, M.; Volmer, D. Restrictions to Pharmacy Ownership and Vertical Integration in Estonia—Perception of Different Stakeholders. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4020018

Gross M, Volmer D. Restrictions to Pharmacy Ownership and Vertical Integration in Estonia—Perception of Different Stakeholders. Pharmacy. 2016; 4(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleGross, Marit, and Daisy Volmer. 2016. "Restrictions to Pharmacy Ownership and Vertical Integration in Estonia—Perception of Different Stakeholders" Pharmacy 4, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4020018

APA StyleGross, M., & Volmer, D. (2016). Restrictions to Pharmacy Ownership and Vertical Integration in Estonia—Perception of Different Stakeholders. Pharmacy, 4(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4020018