1. Introduction

The landscape of pharmacy practice is dramatically changing as pharmacists shift their focus from medication distribution to patient-centered care. To provide this level of care, pharmacists have been challenged to develop new skills and adopt an expanded scope of practice.

At the onset of clinical care, the pharmacist performs a patient assessment to determine any medication related needs. Physical assessment (PA) findings may be an important piece of this patient assessment, and may also be required when pharmacists make decisions to initiate therapy and while managing and monitoring drug therapy [

1].

Although pharmacy curriculums in North America have not traditionally included training in the area of PA, many Canadian and US schools of pharmacy have now incorporated PA into their curriculum [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The Canadian Pharmacist’s Association (CPhA) Blue Print for Pharmacy:

The Vision for Pharmacy acknowledges that future pharmacist education needs to emphasize foundational skills including PA [

5]. Opportunities for PA training and skill development are also required for pharmacists already in practice.

Training for pharmacists in PA has been offered in the US through the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists workshop:

Geriatric Assessment for the Senior Care Pharmacist [

6]. In Alberta, the opportunities for PA training for practicing pharmacists have been limited. A two-hour introductory workshop offered to pharmacists in primary care practices in which participants received instruction on how to perform selected aspects of physical assessment (basic physical exam, measuring blood pressure, and vital signs) and then allowed time to practice. [

7] The participants demonstrated improved confidence in performing the selected PA skills and discussing findings with the healthcare team, but did not show improved confidence in changing drug therapy based on pharmacists’ physical exam findings [

7].

To address the ongoing need for PA training for pharmacists, we proposed that a longer, more intensive educational opportunity would provide clinical pharmacists with the required knowledge and skills in the area of PA to empower them to take an active role in the initiation, management and monitoring of medication therapy [

8,

9]. The objectives of this study were to offer a two-day PA workshop to hospital, ambulatory, and home care pharmacists and evaluate:

The impact on the confidence levels of pharmacists performing PA skills, using PA skills to manage drug therapy, and discussing PA findings;

The level of integration of PA skills into clinical practice;

Changes to practice of pharmacist prescribing.

The workshop consisted of 16 h of instruction by experienced instructors (a physician and pharmacist) recruited from the developers of the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists (ASCP) Geriatric Assessment for the Senior Care Pharmacist Workshop. Course instruction covered the physical assessment techniques for assessing the various body systems and was provided within the context of managing medication therapy. Participants received hands-on instruction as well as guided practice in pairs to demonstrate the physical assessment skills with the assistance of pharmacist facilitators who were previously trained in the area of physical assessment via the same workshop.

3. Results

There were 92 pharmacists from across AHS and Covenant Health that participated in the two-day PA workshops. Consent to participate in the study was obtained from 86 pharmacists. The number of pharmacists responding at each time point was 86 (100%) participants pre and immediately post workshop, 54 (63%) participants at two months, and 49 (57%) for the six-month survey.

3.1. Pre-Workshop

The characteristics and practice areas are summarized for all pharmacists completing the pre-workshop survey (

Table 1). Although almost half of the participants reported using PA at least once monthly in their patient assessment or in drug therapy management, 89% of participants denied receiving formal training in PA. Of the pharmacists who used PA in their practice, the areas or body systems they most commonly assessed were vitals and mental status. Thirty-eight percent of participants had advanced prescribing authority (APA), and 52% were actively pursuing APA. Pharmacists who had been in pharmacy practice for

<10 years accounted for 54% of the participants, and 86% were from urban areas.

Table 1.

Participant pre-workshop characteristics and practice areas.

Table 1.

Participant pre-workshop characteristics and practice areas.

| Demographics | N = 86 respondents (%) |

|---|

| Gender--no./total no. (%)

|

19 (22)

67 (78) |

Highest pharmacy-related education--no./total no. (%)

BSc Pharmacy or equivalent (BScPharm) Accredited residency (ACPR) MSc Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) or PhD

|

59 (69)

20 (23)

0 (0)

7 (8) |

Years of practice--no./total no. (%)

<5 years 6–10 years 11–15 years 16–20 years >20 years

|

28 (33)

18 (21)

11 (13)

7 (8)

22 (26) |

| Additional Prescribing Authority (APA) status--no./total no. (%)

|

33 (38)

45 (52)

8 (9) |

| Pharmacy Practice | |

| Primary Practice Setting *--no./total no. (%)

|

55 (64)

28 (33)

3 (3)

2 (2)

3 (3) |

Practice Location--no./total no. (%)

Rural <10,000 Rural >10,000 Small urban Medium urban Large urban

|

5 (6)

7 (8)

4 (5)

12 (14)

58 (67) |

| Physical Assessment Skills | |

| Formal Physical Assessments (PA) Training--no./total no. (%)

|

76 (89)

9 (11) |

| Frequency of PA use in routine assessment/management of drug therapy--no./total no. (%)

|

42 (49)

21 (25)

12 (14)

3 (4)

4 (8) |

Areas or body systems assessed if PA used--no./total no. (%)

Vital signs (blood pressure, respiratory rate, heart rate) Mental status Neurological exam Head, neck, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and throat Nails, hair, skin Peripheral vascular Musculoskeletal Thorax/Lungs Cardiovascular Abdomen

|

32 (37)

39 (45)

6 (7)

5 (6)

14 (16)

15 (17)

10 (12)

9 (10)

13 (15)

6 (7) |

3.2. Post Workshop

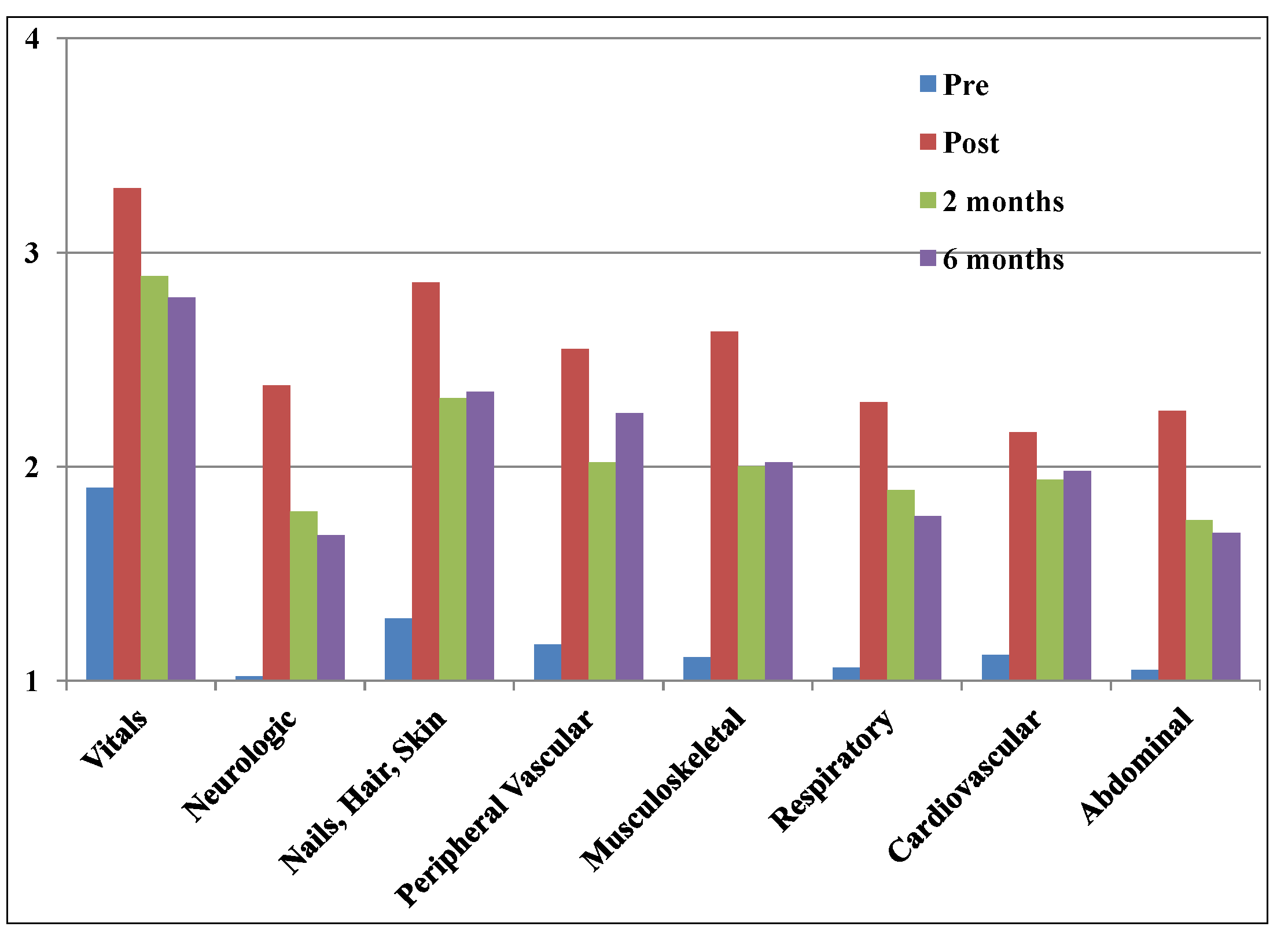

Immediately post workshop, 100% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the knowledge gained in the workshop would enhance their ability to care for their patients. The mean level of confidence in performing individual PA skills increased across all time points compared to pre-workshop, but was higher immediately after the workshop (

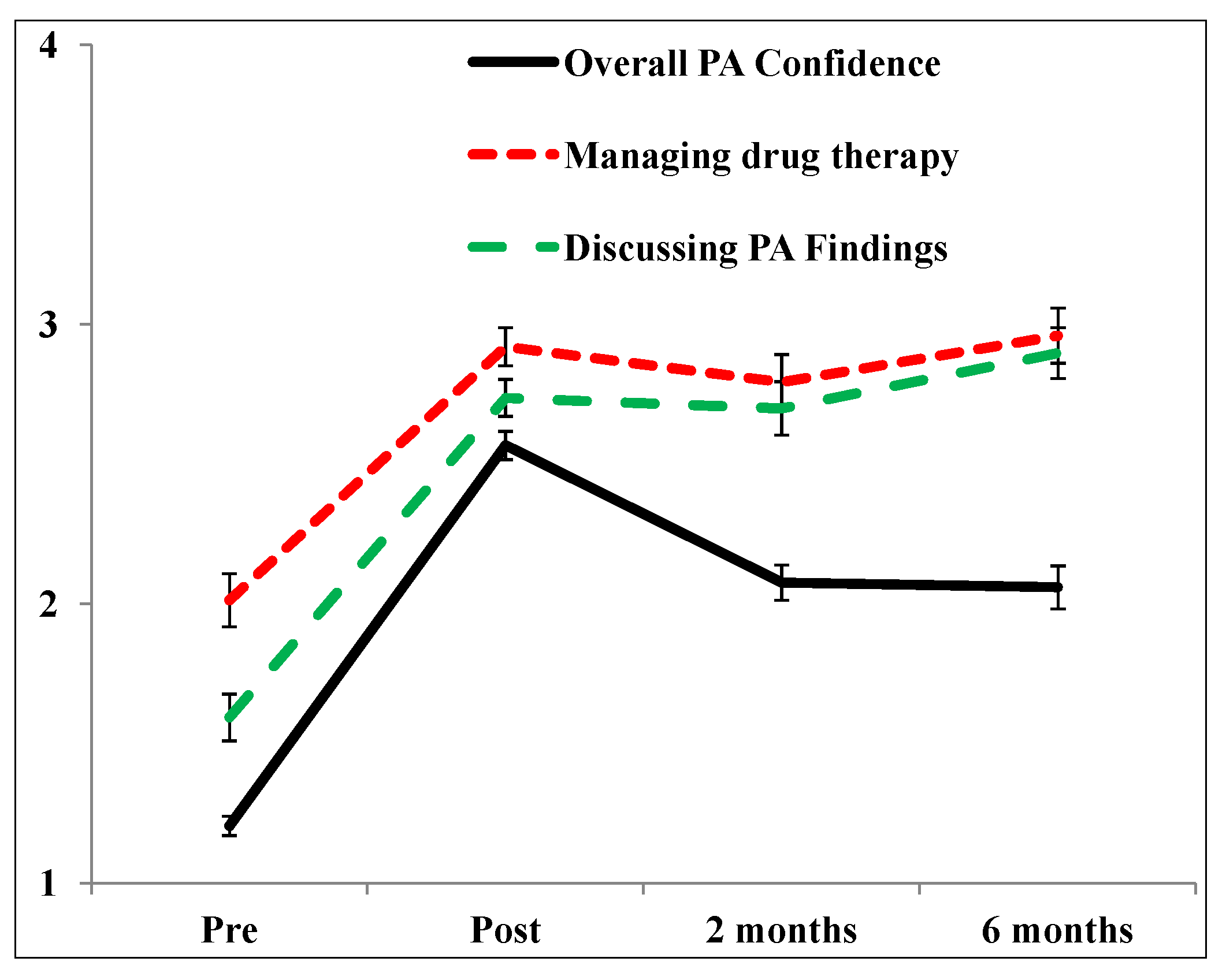

Figure 1). Overall confidence levels performing PA skills, managing drug therapy and discussing PA findings were also increased compared to pre-workshop (

Figure 2). The differences in confidence levels immediately post and six months after the workshop were statistically significant compared to baseline (

Table 2).

Immediately after the workshop, 74% (N = 64) of participants indicated they would increase the frequency or implement the use of PA within their clinical practices, 7% (N = 6) generated ideas for a new clinical practice involving PA, and 19% (N = 16) were unsure of how or did not plan to implement PA within their practice. Of the 33 respondents with APA designation, 91% felt they would have an increased level of confidence in prescribing, while of the pharmacists without APA, 83% indicated that they felt motivated to pursue this designation after the workshop.

Figure 1.

Confidence levels of individual PA skills over duration of study.

Figure 1.

Confidence levels of individual PA skills over duration of study.

*y-axis: 1 = Not confident, 2 = Somewhat confident, 3 = Confident, 4 = Very Confident.

Figure 2.

Mean confidence scores over duration of study.

Figure 2.

Mean confidence scores over duration of study.

y-axis: 1 = Not Confident, 2 = Somewhat Confident, 3= Confident, 4 = Very Confident.

Table 2.

Difference in Confidence Scores Over Duration of Study Compared to Baseline.

Table 2.

Difference in Confidence Scores Over Duration of Study Compared to Baseline.

| | Baseline to Immediate post-workshop | Baseline to 6-months |

|---|

| Overall confidence in PA | 1.36 * | 0.85 * |

| Managing drug therapy based on PA | 0.91 * | 0.95 * |

| Discussing PA findings | 1.14 * | 1.3 * |

At two months, 39% of survey respondents had either increased the number of physical assessments, or implemented PA within their current practices, while 56% had used the knowledge gained from the workshop to enhance their patient assessments without actually performing PA skills.

At six months, 49% of pharmacists continued to incorporate PA into their practices, while 47% were still utilizing the knowledge from the program within their patient assessments. At six months, four survey respondents indicated that they had received their APA since attending the workshop.

When asked about barriers to implementing the skills within their practices, 46% indicated that they felt they did not need to perform PA as they already had access to the necessary information from other health care professionals’ assessments (

Table 3). Additionally, pharmacists identified lack of adequate training (21%), lack of comfort in performing PA (21%), over-stepping their professional role (16.5%), and not having enough time (12.5%) were barriers to performing physical assessment.

Table 3.

Barriers to implementing Physical Assessment *.

Table 3.

Barriers to implementing Physical Assessment *.

| Barrier | Number of respondents identifying (%) * |

|---|

| | 22 (46) |

| | 11 (21) |

| | 11 (21) |

| | 8 (16) |

| | 6 (12.5) |

| | 5 (10.4) |

| | 1 (2.1) |

| | 1 (2.1) |

| Other § |

11 (21) |

4. Discussion

This two-day PA workshop for institutional pharmacists revealed that a continuing professional development opportunity translated into overall improved confidence in performing PA skills, and increased the level of integration of PA into clinical practice. This was demonstrated by increased confidence in discussing PA findings and making drug therapy decisions based on PA findings. Such an opportunity lends support to a growing field of study examining the greater impact of continuing professional development models compared to traditional continuing education programs [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. These models differ in their approach to address the learning needs of health professionals. Continuing professional development is rooted in the idea that health professionals are engaged in lifelong learning and that each health professional is best suited to determine their own personal learning goals based upon their unique practice setting. One central component to continuing professional development is health professionals are motivated and self-directed, assuming responsibility to identify their learning needs and reflect upon their progress [

12]. In contrast, continuing education forms just one component of the spectrum in continuing professional development, and has traditionally employed a didactic approach to meet regulatory requirements for competency assessment [

12].

In this study, participants’ formal training in PA was limited. Despite this lack of training, just over half of the pharmacists in our study reported already performing some kind of PA in their assessment and management of drug therapy at baseline. The reason for greater utilization of PA may be related to the fact 38% of pharmacists had APA status, that all the pharmacists practiced in an institutional setting, and that one third of participants were practicing for less than five years. Those with APA may be expected to incorporate PA into their practice to a greater extent because part of the assessment in independently initiating therapy for a patient can involve physical assessment. The institutional setting may offer more opportunities for PA with better access to PA instruments, support from other health care providers, and peer encouragement. Furthermore, as schools of pharmacy begin to incorporate PA into their curriculum, new graduates of these programs may feel more comfortable utilizing these skills having some background through formal PA education [

2,

3,

4].

While a previous study evaluating a physical assessment workshop [

7] did not show improvement in using PA findings to make changes in drug therapy, this course succeeded in improving a pharmacist’s confidence to use their own PA findings to support recommendations to alter drug therapy. This may be attributed to the longer duration of the workshop which allowed pharmacists to better practice the skills and consolidate their knowledge. Furthermore, this study had a longer duration of follow-up, 6 months compared to 4 weeks, which ensured that an adequate period had elapsed since the workshop to capture the ability for pharmacists to incorporate PA into their own unique practice environment.

Pharmacists who participated in a 12-week professional development course on laboratory values, which incorporated the CPD model, were able to describe specific changes in their practice after completion of the training [

15]. The pharmacists in our study described practice change as it related to the incorporation of PA skills and use of APA. The data is reassuring in that the workshop achieved increased incorporation of PA skills into daily practice as demonstrated by the increased confidence in managing drug therapy based on PA findings and discussing PA findings.

It is interesting to note that while overall mean PA confidence scores over the duration of the study remained statistically higher from baseline to six months post, there was a trend in decreasing confidence from immediately post workshop to two months, and a slight decrease from two months to six months. This may be due to the lack of mentorship after the workshop and/or lack of revisiting or applying the skills over time. Ongoing mentorship is a factor in ensuring that professional development courses are sustainable. Bungard

et al. showed that incorporating peer mentorship beyond an anticoagulation professional development course was an effective strategy in improving pharmacists’ knowledge, confidence, and daily practice [

16]. In a study by Austin

et al., pharmacists participating in a focus group to identify attitudes, behaviors, and preferences towards continuing professional development agreed that workplace learning and peer support is an essential component in maintaining professional development knowledge and skills [

17]. Performance-based feedback can also serve as another strategy to further enhance pharmacists’ skills since many professionals have difficulty identifying and correcting their deficiencies appropriately [

18]. Such data highlights the importance of practicing and applying the knowledge learned to a real life practice setting with appropriate peer or mentor feedback to prevent decline of skills over time. Another potential reason for the decreasing trend in overall confidence over time is that pharmacists may have only focused on using selected skills, if any,

versus all that were covered in the workshop on a regular basis. Pharmacists’ confidence in managing drug therapy and discussing PA findings did remain consistently high across the duration of the study and this may have been reflective of the use of selected skills as it pertained to their specific area of practice and the drug therapy they most consistently manage.

The study done by Barry

et al., found that most pharmacist participants did not use physical examination in their practice, primarily due to a lack of formal training [

7]. Other barriers to performing physical exams included lack of comfort; access to physical exam information already performed by other health care professionals, and perceived lack of value in performing physical exams [

7]. Similar barriers were identified by participants in this workshop.

While this study sought to address the drawbacks acknowledged in previous research [

7] there are still some limitations. First, this was a survey based study with voluntary recruitment of participants so inherently there may be a response bias leading towards positive results. Additionally, this was a professional development opportunity and one key feature of continuing professional development courses is that the professional takes responsibility for their own self-directed learning and hence participants already have a vested interest in the course [

18]. Some pharmacists may also have been reluctant to report that they did not incorporate PA into their practice and may have either selected responses that were desired or not responded to the survey at all. There were fewer respondents at each subsequent time point in the survey; however this study had an acceptable response rate that exceeded half of the sample at its lowest response point [

19].

The population characteristics of participants in this study may not be representative of the general pharmacist population as there was a greater proportion with advanced training or degrees, and with APA status. According to data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, 1.9% of the pharmacist workforce in Alberta in 2012 had a doctor of pharmacy degree, and 2.4% had an accredited residency [

20]. Although the current rate of APA status in Alberta is at 10%, 38% of participating pharmacists had this designation [

21].

Competence, performance, patient satisfaction and outcomes were not assessed as it was beyond the scope of this study, however future research should consider implementing an objective means to assess pharmacist impact in these areas as it relates to PA. To enhance feasibility, one area of PA such as measuring vital signs, could be the focus. Expansion of the workshop to include community pharmacists as well as rural clinicians may provide insight into the impact environment and accessibility to resources has on sustainable practice change for a pharmacist PA workshop.

This study examined the impact of the workshop in influencing practice change for those with and without APA status. Aside from a PA workshop, another area to explore is what other factors may impact a pharmacists’ likelihood of obtaining APA. These include the team environment they work in, physician or nurse practitioner support, pharmacy work flow and APA status of other colleagues sharing the team workload, as well as individual attitudes and priorities of pharmacists.