Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| CHEMSCI | PHYSMATH | BIOLSCI | PHARMTECH | MEDISCI | LAWSOC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | ||||||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 33 ± 7 | 8 ± 3 | 21 ± 6 | 13 ± 5 | 19 ± 7 | 6 ± 5 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 21 | 38 | 29 | 38 | 37 | 83 |

| 2011 | ||||||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 26 ± 11 | 7 ± 2 | 13 ± 5 | 14 ± 5 | 28 ± 8 | 5 ± 3 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 42 | 29 | 38 | 36 | 29 | 60 |

| CHEMSCI | PHYSMATH | BIOLSCI | PHARMTECH | MEDISCI | LAWSOC | GENERIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 44.0 | 2.0 | 22.0 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Belgium | 24.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 18.0 | 27.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 |

| Bulgaria | 31.0 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 24.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Croatia | 24.9 | 4.2 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 26.9 | 2.5 | 23.3 |

| Czech Republic | 17.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 22.0 | 19.0 | 13.0 | 16.0 |

| Denmark | 42.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 9.0 | 3.0 |

| Estonia | 21.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 21.0 | 39.0 | 10.0 | 3.0 |

| Finland | 20.0 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 21.9 | 28.8 | 15.6 | 5.6 |

| France | 17.6 | 9.5 | 17.9 | 5.9 | 42.0 | 2.2 | 5.0 |

| Germany | 39.8 | 4.5 | 10.9 | 13.4 | 28.3 | 2.1 | 3.8 |

| Greece | 39.3 | 5.8 | 14.2 | 8.2 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 14.0 |

| Hungary | 27.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 16.0 | 28.5 | 3.9 | 14.2 |

| Ireland | 13.6 | 11.1 | 7.1 | 18.3 | 35.5 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| Italy | 32.4 | 7.2 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 31.5 | 4.8 | 2.2 |

| Latvia | 27.7 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 20.2 | 26.6 | 8.5 | 6.4 |

| Lithuania | 21.3 | 2.0 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 27.7 | 7.4 | 23.8 |

| Malta | 15.4 | 7.2 | 12.7 | 15.4 | 30.8 | 3.6 | 15.0 |

| Netherlands | 20.1 | 3.9 | 10.6 | 14.2 | 31.1 | 8.3 | 11.8 |

| Poland | 21.3 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 15.9 | 38.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Portugal | 19.6 | 6.8 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 32.2 | 12.0 | 1.2 |

| Rumania | 26.1 | 8.7 | 15.8 | 14.1 | 24.9 | 3.7 | 6.6 |

| Slovakia | 28.8 | 8.8 | 10.9 | 14.4 | 27.6 | 3.4 | 6.0 |

| Slovenia | 27.0 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 22.0 | 21.0 | 8.5 | 4.7 |

| Spain | 23.5 | 5.5 | 19.9 | 11.0 | 27.6 | 5.5 | 7.0 |

| Sweden | 18.3 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 19.5 | 21.5 | 11.8 | 5.0 |

| United Kingdom | 13.6 | 5.7 | 23.9 | 22.7 | 23.9 | 3.4 | 6.8 |

| Mean | 25.3 | 6.4 | 11.2 | 15.3 | 27.4 | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| Standard deviation | 8.6 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 6.1 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 33.9 | 38.4 | 48.5 | 31.2 | 25.0 | 61.8 | 74.3 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology.

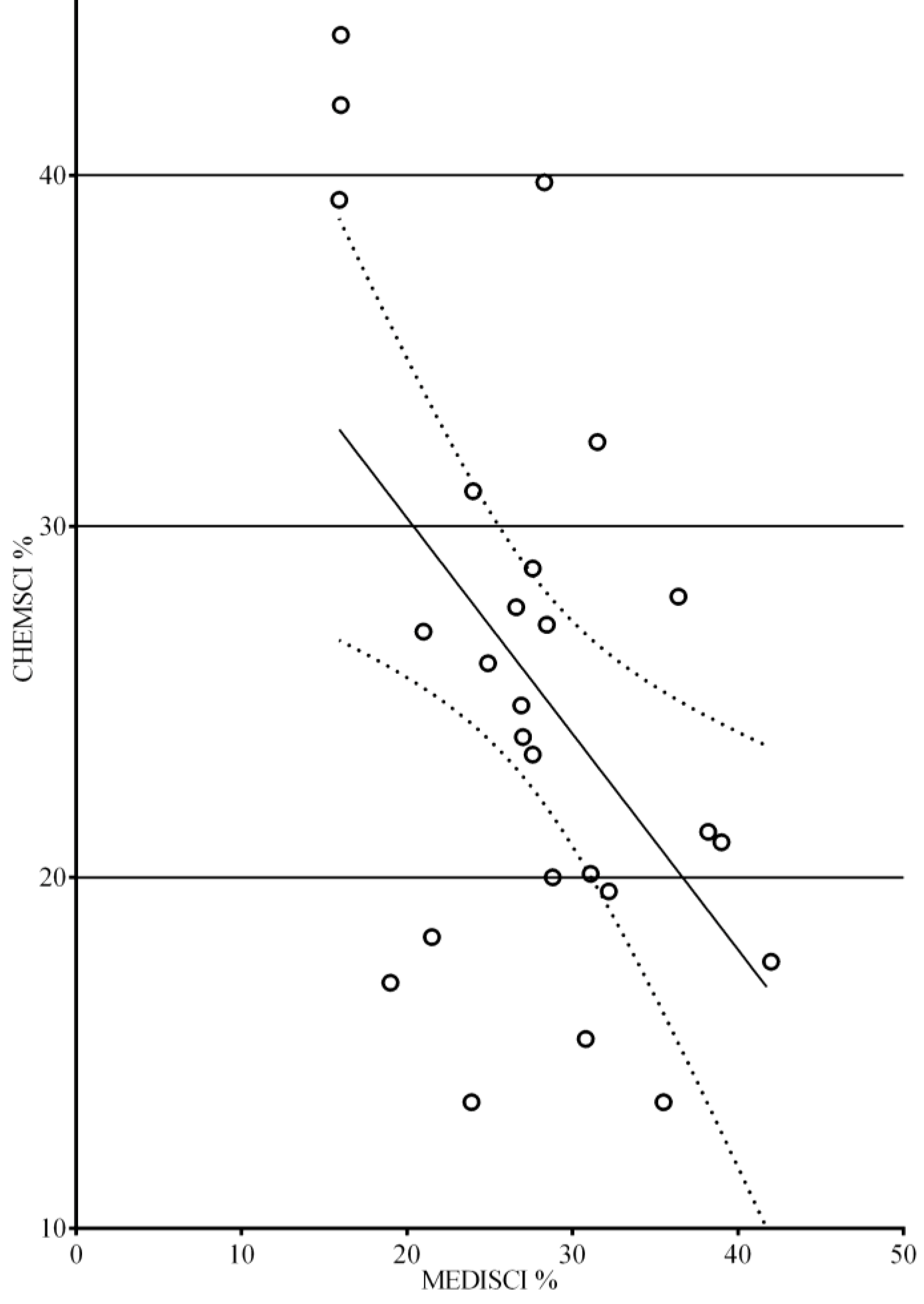

4.2. Evolution in Subject Areas between the 1994 and 2011 Surveys

4.3. A More “Clinical” Education and Practice in Pharmacy?

- (1)

- safe and efficacious medicinal products

- (2)

- provision of information and advice on medicinal products…including on their appropriate use

- (3)

- reporting of adverse reactions of pharmaceutical products

- (4)

- provision of personalised support for patients

- (5)

- contribution to local or national public health campaigns

- (a)

- preparation of the pharmaceutical form of medicinal products

- (b)

- manufacture and testing of medicinal products

- (c)

- testing of medicinal products in a laboratory for the testing of medicinal products

- (d)

- storage, preservation and distribution of medicinal products at the wholesale stage

- (e)

- supply, preparation, testing, storage, distribution and dispensing of safe and efficacious medicinal products of the required quality in pharmacies open to the public

- (f)

- preparation, testing, storage and dispensing of safe and efficacious medicinal products of the required quality in hospitals

- (g)

- provision of information and advice on medicinal products as such, including on their appropriate use

- (h)

- reporting of adverse reactions of pharmaceutical products to the competent authorities

- (i)

- personalised support for patients who administer their medication

- (j)

- contribution to local or national public health campaigns

5. Conclusions

- Since the 1990s there has been no decrease in the variability in pharmacy courses amongst departments in different countries. This raises the question of the difference between the notion of “the broad comparability of training courses in the Member States” as outlined in the 1985 EEC directive, and the reality of the variability of EU pharmacy education systems.

- In the EU, there has been a shift towards more “clinical” courses with a greater MEDISCI content. This global shift from courses oriented towards chemical sciences to those oriented towards medicinal sciences coincides with the recognition—in the latest version of the EU directive—of a more important “clinical” role for pharmacists.

Appendix

| Subject Areas in Directive 85/432/EEC | Additional Subjects |

|---|---|

| 1. Chemistry | |

| (CHEMSCI) | |

| General and inorganic chemistry | Medical physico-chemistry |

| Organic chemistry | Pharmacopeia analysis |

| Analytical chemistry | |

| Pharmaceutical chemistry including analysis | |

| of medicinal products | |

| Structure-activity relationships / drug design | |

| 2. Physics / Mathematics / Computing / Statistics | |

| (PHYSMATH) | |

| Physics | Mathematics / Computing / Statistics |

| Pharmaceutical calculations | |

| Information technology, information technology applied to community pharmacy, information technology applied to national healthcare | |

| Experimental design and analysis | |

| 3. Biology / Biochemistry / Pharmacognosy (BIOLSCI) | |

| General and applied biochemistry (medical) | Phyto-chemistry |

| Plant and animal biology | |

| Microbiology/Pharmacognosy | |

| Mycology | |

| Molecular biology | |

| Genetics | |

| 4. Pharmaceutics / Technology | |

| (PHARMTECH) | |

| Pharmaceutical technology | Finished medicinal products |

| Drug disposition and metabolism / pharmacokinetics | |

| Novel drug delivery systems | |

| Pharmaceutical research and development | |

| Drug production | |

| Quality assurance in production | |

| Drug / new chemical entity registration and regularization Common technical document: pharmaceutical quality, safety pharmacology and toxicology efficacy (preclinical and clinical studies) Ophthalmic preparations | |

| Medical gases | |

| Cosmetics | |

| Management strategy in industry Economics of the pharmaceutical industry and of research and development | |

| 5. Medicine / Pharmacology / Toxicology | |

| (MEDISCI) | |

| Anatomy, physiology, medical terminology | Pathology / Histology / Nutrition |

| Pharmacology / pharmacotherapy | Haematology / Immunology |

| Toxicology | Parasitology / Hygiene |

| Emergency therapy | |

| Non-pharmacological treatment | |

| Clinical chemistry / bio-analysis (of body fluids) | |

| Radiochemistry | |

| Dispensing process, drug prescription, prescription analysis (detection of adverse effects and drug interactions) | |

| Generic drugs | |

| Planning, running and interpretation of the data of clinical trials | |

| Medical devices | |

| Orthopaedics | |

| OTC medicines, complementary therapy | |

| At-home support and care | |

| Skin illness and treatment | |

| Homeopathy | |

| Phyto-therapy | |

| Drugs in veterinary medicine | |

| Pharmaceutical care, pharmaceutical therapy of illness and disease | |

| 6. Law / Social Aspects of Pharmacy (LAWSOC) | |

| Legislation / professional ethics | Philosophy / Economics |

| Management / History of pharmacy | |

| Public health | |

| Social sciences | |

| Forensic science | |

| Public health / health promotion | |

| Quality management | |

| Epidemiology of drug use (pharmaco-epidemiology) | |

| Economics of drug use (pharmaco-economics) | |

| 7.Generic Competences (GENERIC) | |

| General knowledge | |

| Academic literacy | |

| Languages | |

| First aid | |

| Communication | |

| Management | |

| Practical skills |

Acknowledgments

- C. Noe. University of Vienna. Austria.

- B. Rombaut. H. Halewijck and B. Thys. Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Dept. Pharmaceutical Biotechnology and Molecular Biology. Brussels. Belgium.

- V. Petkova and S. Nikolov. University of Sofia. Faculty of Pharmacy. Sofia. Bulgaria.

- V. Belcheva. Sanofi-Aventis. Sofia. Bulgaria.

- M. Z. Končić. University of Zagreb. Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry. Zagreb Croatia.

- D. Jonjic. Croatian Chamber of Pharmacists. Zagreb. Croatia.

- Crnkovic. Hospital pharmacy. Psychiatry Clinic. Zagreb. Croatia.

- M. Polasek. Faculty of Pharmacy. Charles University. Prague. Czech Republic.

- U. Madsen and B. Fjalland. Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences. University of Copenhagen. Denmark.

- M. Brandl. Faculty of Science. University of Southern Denmark. Denmark.

- M. Ringkjøbing-Elema. EIPG / The Association of Danish Industrial Pharmacists. Copenhagen. Denmark.

- P. Veski and D. Volmer. Department of Pharmacy. University of Tartu. Tartu. Estonia.

- J. Hirvonen and A. Juppo. University of Helsinki. Faculty of Pharmacy. Finland.

- Capdeville-Atkinson. Lorraine University. Nancy. France.

- Marcincal. Faculté de Pharmacie. Université de Lille 2. Lille. France.

- V. Lacamoire and I. Baron. Conseil National de l’Ordre des Pharmaciens. Paris. France.

- R. Süss and R. Schubert. University of Freiburg. Freiburg. Germany.

- P. Macheras. E. Mikros and D. M. Rekkas. School of Pharmacy. University of Athens. Athens. Greece.

- K. Poulas. School of Pharmacy. University of Patras. Patras. Greece.

- G. Soos and P. Doro. Faculty of Pharmacy. University of Szeged. Szeged. Hungary.

- J. Strawbridge and P. Gallagher. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Dublin. Ireland.

- L. Horgan. Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland. PSI—The Pharmacy Regulator. Dublin. Ireland.

- Rossi. and P. BLASI Faculty of Pharmacy. University of Perugia. Perugia. Italy.

- R. Muceniece. Faculty of Medicine of University of Latvia. Riga. Latvia.

- Maurina. Faculty of Pharmacy. Riga. Latvia.

- Saprovska. Latvian Branch. European Industrial Pharmacists’ Group (EIPG). Riga. Latvia.

- V. Briedis and M. Sapragoniene. Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Kaunus. Lithuania.

- L. M. Azzopardi and A. S. Inglott. University of Malta. Department of Pharmacy. Msida. Malta.

- T. Schalekamp. Utrecht University. Faculty of Science. Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Utrecht. The Netherlands.

- H. J. Haisma. University of Groningen. School of Life Sciences. Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical

- Sciences. Groningen. The Netherlands.

- S. Polak and R. Jachowicz. Faculty of Pharmacy with Division of Medicinal Analysis.

- Jagiellonian University Medical College. Krakow. Poland.

- J. A. G. Morais and A.M. Cavaco. Faculdade de Farmácia Universidade de Lisboa. Lisbon. Portugal.

- Mircioiu and C. Rais. Faculty of Pharmacy. University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Carol

- Davila”. Bucharest. Romania.

- J. Kyselovič and M. Remko. Faculty of Pharmacy. Comenius University. Odbojarov 10. Bratislava. 83232. Slovakia.

- Bozic and S. Gobec. University of Ljubljana. Faculty of Pharmacy. Ljubljana. Slovenia.

- B. DEL Castillo-Garcia. Facultad de Farmacia. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid. Spain.

- L. Recalde and A. Sanchez Pozo. Facultad de Farmacia. Universidad de Granada. Granada. Spain.

- R. Hansson and E. Björk. Faculty of Pharmacy. Uppsala University; G. TOBIN. Sahlgrenska Academy. Sweden.

- K. A Wilson. Aston Pharmacy School. Aston. UK.

- G. B. Lockwood. University of Manchester. School of Pharmacy. Manchester. UK.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council Directive of 16 September 1985 concerning the coordination of provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in respect of certain activities in the field of pharmacy. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31985L0432&from=EN (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- European Association of Faculties of Pharmacy (EAFP). Available online: http://eafponline.eu/ (accessed on 3 August 2014).

- ERASMUS Subject Evaluations: Summary Reports of the Evaluation Conferences by Subject Area. pharmacy. volume 1. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/education/erasmus/doc/publ/conf_en.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- PHARMINE: pharmacy education in Europe. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- EU directive 2013/55/EU on the recognition of professional qualifications. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:255:0022:0142:EN:PDF (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Bourlioux, P. Proceedings of the 2nd European meetings of the faculties, schools and institutes of pharmacy. Berlin, September 1994; Available online: http://enzu.pharmine.org/media/filebook/files/Bourlioux_full_report.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- The PHARMINE WP7 survey. Available online: http://enzu.pharmine.org/media/filebook/files/PHARMINE%20WP7%20survey%20of%20European%20HEIs%200309.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Atkinson, J; Rombaut, B. The 2011 PHARMINE report on pharmacy and pharmacy education in the European Union. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 9, 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J,; Rombaut, B. The PHARMINE study on the impact of the European Union directive on sectoral professions and of the Bologna declaration on pharmacy education in Europe. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 9, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães Morais, J.A.; Cavaco, A.M.; Rombaut, B.; Rouse, M.; Atkinson, J. Quality assurance in European pharmacy education and training. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 9, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for deviations of distribution from normality. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/www/data-analysis-resource-center/blog/new-in-prism-6-kolmogorov-smirnov-test/ (accessed on 3 August 2014).

- Raschi, D.; Guiard, V. The robustness of parametric statistical methods. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 4, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey test for multiple comparisons. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/6/statistics/index.htm?stat_the_methods_of_tukey_and_dunne.htm (accessed on 3 August 2014).

- Holm-Šídák test for multiple comparisons. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/6/statistics/index.htm?stat_holms_multiple_comparison_test.htm (accessed on 3 August 2014).

- GraphPad®. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Country profiles on the PHARMINE website. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/losse_paginas/Country_Profiles/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Erasmus. Available online: https://www.erasmusplus.org.uk/ (accessed on 3 August 2014).

- European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/education/tools/docs/ects-guide_en.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2014).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Atkinson, J. Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe. Pharmacy 2014, 2, 231-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2030231

Atkinson J. Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe. Pharmacy. 2014; 2(3):231-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2030231

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtkinson, Jeffrey. 2014. "Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe" Pharmacy 2, no. 3: 231-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2030231

APA StyleAtkinson, J. (2014). Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe. Pharmacy, 2(3), 231-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2030231