Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Drug Dispensing Data of Older Adults Living in Northwest Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Population

2.3. PIMs

- For dosage limits, the unit dose of dispensed medications was considered rather than the prescribed dose (missing data).

- For concomitant uses, a period of 3 months was considered to check the co-dispensing of the drug classes concerned, in accordance with methodologies reported elsewhere [18].

- For uses > 8 weeks, the distance between consecutive dispensing events was measured, and drugs dispensed more than 56 days apart and within 180 days were considered PIMs.

- Drug use was considered chronic when there were 5 or more dispensing events of the drug in a year. This is a definition commonly used in drug utilization research [19].

- Pharmaceutical forms and administration routes were derived from medication names.

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Samples

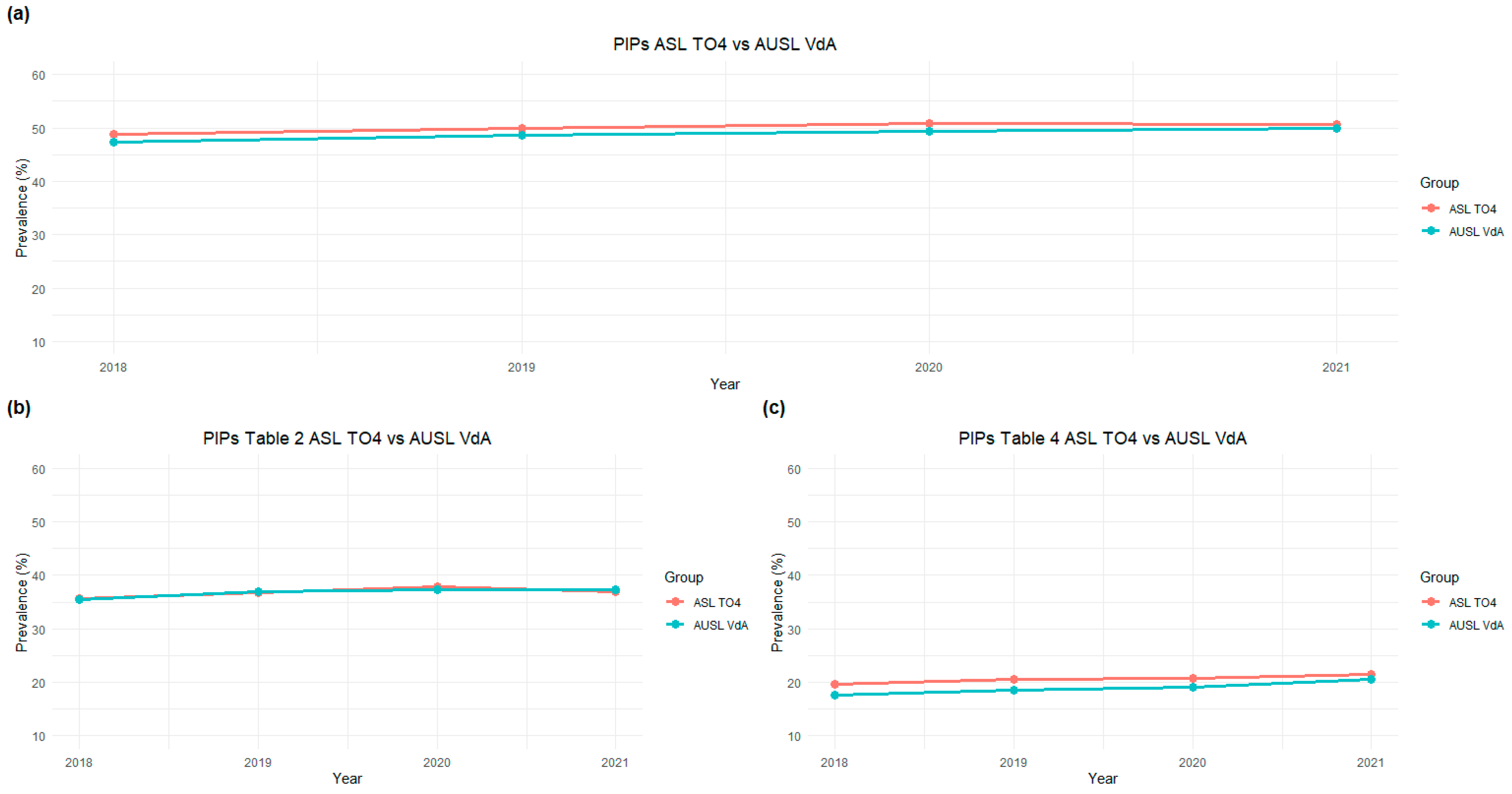

3.2. Temporal Trends According to PIM Type: Drugs to Avoid and Drugs to Be Used with Caution

3.3. Use of Drugs with Strong Anticholinergic Properties by Older Adults

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boateng, I.; Rodriguez Pascual, C.; Grassby, P.; Asghar, Z. The impact of potentially inappropriate medicines on adverse clinical outcomes in the aged: A retrospective cohort study. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2025, 18, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, F.; Casula, M.; Scotti, L.; Olmastroni, E.; Ferrante, D.; Ucciero, A.; Tragni, E.; Catapano, A.L.; Barone-Adesi, F. Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing among Elderly Outpatients: Evaluation of Temporal Trends 2012–2018 in Piedmont, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre. Medicines Use in Italy. Year 2023; Italian Medicines Agency: Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Piccoliori, G.; Mahlknecht, A.; Sandri, M.; Valentini, M.; Vögele, A.; Schmid, S.; Deflorian, F.; Engl, A.; Sönnichsen, A.; Wiedermann, C. Epidemiology and associated factors of polypharmacy in older patients in primary care: A northern Italian cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, M.H.; Ouslander, J.G.; Rollingher, I.; Reuben, D.B.; Brooks, J.; Beck, J.C. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch. Intern. Med. 1991, 151, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2052–2081. [CrossRef]

- Allegri, N.; Rossi, F.; Del Signore, F.; Bertazzoni, P.; Bellazzi, R.; Sandrini, G.; Vecchi, T.; Liccione, D.; Pascale, A.; Govoni, S. Drug prescription appropriateness in the elderly: An Italian study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M.; Novella, A.; Ianes, A.; Pasina, L. Potentially Inappropriate Psychotropic Drugs in Nursing Homes: An Italian Obser-vational Study. Drugs Aging 2024, 41, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zito, S.; Poluzzi, E.; Pierantozzi, A.; Onder, G.; Da Cas, R.; Ippoliti, I.; Lunghi, C.; Cangini, A.; Trotta, F. Medication use in Italian nursing homes: Preliminary results from the national monitoring system. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1128605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifirò, G.; Gini, R.; Barone-Adesi, F.; Beghi, E.; Cantarutti, A.; Capuano, A.; Carnovale, C.; Clavenna, A.; Dellagiovanna, M.; Ferrajolo, C.; et al. The Role of European Healthcare Databases for Post-Marketing Drug Effectiveness, Safety and Value Evaluation: Where Does Italy Stand? Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglio, G.; Basso, L.; Armando, L.G.; Traina, S.; Benetti, E.; Diarassouba, A.; Parisi, R.B.; Esiliato, M.; Rolando, C.; Remani, E.; et al. A network approach for the study of drug prescriptions: Analysis of ad-ministrative records from a local health unit (ASL TO4, Regione Piemonte, Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, L.G.; Baroetto Parisi, R.; Remani, E.; Esiliato, M.; Rolando, C.; Vinciguerra, V.; Diarassouba, A.; Cena, C.; Miglio, G. Persistence to Medications for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia/Benign Prostatic Obstruction-Associated Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the ASL TO4 Regione Piemonte (Italy). Healthcare 2022, 10, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, L.G.; Miglio, G.; Baroetto Parisi, R.; Esiliato, M.; Rolando, C.; Vinciguerra, V.; Diarassouba, A.; Cena, C. Assessing Therapeutic Choices and Adherence to Antidiabetic Therapy in Naïve Patients: A Retrospective Observational Study in a Local Health Authority of the Piedmont Region (Italy). Healthcare 2023, 11, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment, 2025; Norwegian Institute of Public Health: Oslo, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Linea Guida per la Classificazione e Conduzione Degli Studi Osservazionali sui Farmaci. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/linea-guida-per-la-classificazione-e-conduzione-degli-studi-osservazionali-sui-farmaci (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Rapporto ISS COVID-19 N. 6/2021—Assistenza Sociosanitaria Residenziale agli Anziani non Auto-sufficienti: Profili Bioetici e Biogiuridici. Versione del 10 Marzo 2021. Available online: https://www.iss.it/rapporti-covid-19/-/asset_publisher/btw1J82wtYzH/content/rapporto-iss-covid-19-n.-6-2021-assistenza-sociosanitaria-residenziale-agli-anziani-non-autosufficienti-profili-bioetici-e-biogiuridici.-versione-del-10-marzo-2021 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Rasmussen, L.; Wettermark, B.; Steinke, D.; Pottegård, A. Core concepts in pharmacoepidemiology: Measures of drug utilization based on individual-level drug dispensing data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2022, 31, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, S.R.; Hitchner, L.; Harrison, H.; Gerstenberger, J.; Steiger, S. Predictors of higher-risk chronic opioid prescriptions in an aca-demic primary care setting. Subst. Abus. 2016, 37, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2227–2246. [CrossRef]

- Regione Piemonte. Piemonte Statistica e B.D.D.E. Available online: http://www.ruparpiemonte.it/infostat/index.jsp (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Demo—Demografia in Cifre. Available online: https://demo.istat.it/app/?i=POS (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Aging Brain Program of the Indiana University Center for Aging Research. Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale. 2012 Update. Available online: https://www.hii.iu.edu/resources/anticholinergic-cognitive-burden-scale.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Casula, M.; Menditto, E.; Galimberti, F.; Russo, V.; Olmastroni, E.; Scotti, L.; Orlando, V.; Corrao, G.; Catapano, A.L.; Tragni, E. A pragmatic controlled trial to improve the appropriate prescription of drugs in adult outpatients: Design and rationale of the EDU.RE.DRUG study. Prim. Health Care Res. 2020, 21, E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggli, Y.; Halfon, P.; Zeukeng, M.J.; Kherad, O.; Schaller, P.; Raetzo, M.-A.; Klay, M.F.; Favre, B.M.; Schaller, D.; Marti, J. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Dispensing in Outpatients: Com-parison of Different Measurement Approaches. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2023, 16, 2565–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovstadius, B.; Petersson, G.; Hellström, L.; Ericson, L. Trends in Inappropriate Drug Therapy Prescription in the Elderly in Sweden from 2006 to 2013: Assessment Using National Indicators. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elli, C.; Novella, A.; Pasina, L. Proton pump inhibitors and 1-year risk of adverse outcomes after discharge from internal medicine wards: An observational study in the REPOSI cohort. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2025, 20, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepisi, R.; Fusco, S.; Sganga, F.; Falcone, B.; Vetrano, D.L.; Abbatecola, A.; Corica, F.; Maggio, M.; Ruggiero, C.; Fabbietti, P.; et al. Inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors in elderly patients discharged from acute care hospitals. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 20, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota AIFA 01. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/nota-01 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nota AIFA 48. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/nota-48 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Casula, M.; Ardoino, I.; Pierini, L.; Perrella, L.; Scotti, S.; Mucherino, S.; Orlando, V.; Menditto, E.; Franchi, C. Inappropriate prescribing of drugs for peptic ulcer and gastro-esophageal reflux disease remains a matter of concern: Results from the LAPTOP-PPI cluster randomized trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1430879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, L.; Bellini, E.; Galvano, L.; Giustini, S. La deprescrizione degli inibitori di pompa: Una pratica necessaria per il medico di medicina generale. Riv. Soc. Ital. Di Med. Gen. 2017, 6, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bali, V.M.; Chatterjee, S.; Carnahan, R.M.; Chen, H.; Johnson, M.L.; Aparasu, R.R. Risk of Dementia Among Elderly Nursing Home Patients Using Paroxetine and Other Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanah, L.R.; Goldhirish, J.L.; Huey, L.Y.; Piper, B.J. Specialty-Type and State-Level Variation in Paroxetine Use Among Older Adult Patients. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.02.15.23285973v1 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Marks, D.M.; Park, M.H.; Ham, B.J.; Han, C.; Patkar, A.A.; Masand, P.S.; Pae, C.-U. Paroxetine: Safety and tolerability issues. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2008, 7, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevels, R.M.; Gontkovsky, S.T.; Williams, B.E. Paroxetine—The Antidepressant from Hell? Probably Not, But Caution Required. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2016, 46, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osservatorio Nazionale sull’Impiego dei Medicinali. L’uso dei farmaci in Italia. In Rapporto Nazionale Anno 2018; Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Alternatives Panel; Steinman, M.A. Alternative Treatments to Selected Medications in the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria®. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2025, 73, 2657–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, L.G.; Miglio, G.; de Cosmo, P.; Cena, C. Clinical decision support systems to improve drug prescription and therapy optimization in clinical practice: A scoping review. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2023, 30, e100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area 1: ASL TO4 | |||||

| Total, n (%) | 65,807 | 44,397 (63.4) | 48,491 (69.2) | 50,731 (72.4) | 54,028 (77.1) |

| Males, n (%) | 26,552 (40.3) | 17,234 (38.8) | 19,181 (39.6) | 20,380 (40.2) | 21,742 (40.2) |

| Age, median [IQR] | 77 [72–82] | 78 [73–83] | 77 [72–82] | 76 [71–82] | 76 [71–82] |

| Age range, n (%) | |||||

| 65–74 years | 28,391 (40.5) | ||||

| 75–84 years | 27,076 (38.6) | ||||

| ≥85 years | 10,340 (14.8) | ||||

| PIMs per patient, median [IQR] | 19 [6–37] | 8 [4–13] | 7 [3–12] | 7 [4–11] | 7 [4–11] |

| Patients with PIMs to avoid, n (%) a | 46,928 (71.3) | 32,363 (72.9) | 35,721 (73.7) | 37,741 (74.4) | 39,535 (73.2) |

| Patients with PIMs to be used with caution, n (%) b | 34,618 (52.6) | 17,916 (40.4) | 19,848 (40.9) | 20,768 (40.9) | 22,841 (42.3) |

| Patients with anticholinergic PIMs, n (%) c | 7678 (11.7) | 3975 (51.5) | 4197 (54.7) | 4304 (56.1) | 4685 (61.0) |

| Area 2: AUSL VdA | |||||

| Total, n | 14,359 | 9662 (62.9) | 10,198 (69.0) | 11,251 (73.3) | 12,036 (78.4) |

| Males, n (%) | 5796 (40.4) | 3770 (39.0) | 4190 (39.5) | 4510 (40.1) | 4879 (40.5) |

| Age, median [IQR] | 77 [72–83] | 78 [73–83] | 77 [72–83] | 77 [72–82] | 77 [71–82] |

| Age range (years) | |||||

| 65–74 years | 6055 (39.4) | ||||

| 75–84 years | 5928 (38.6) | ||||

| ≥85 years | 2376 (15.5) | ||||

| PIMs per patient, median [IQR] | 20 [6–39] | 7 [3–13] | 7 [3–12] | 7 [4–12] | 7 [4–12] |

| Patients with PIMs to avoid, n (%) a | 10,519 (73.3) | 7241 (74.9) | 8058 (76.0) | 8542 (75.9) | 9000 (74.8) |

| Patients with PIMs to be used with caution, n (%) b | 7318 (51.0) | 3589 (37.1) | 4056 (38.3) | 4366 (38.8) | 4948 (41.1) |

| Patients with anticholinergic PIMs, n (%) c | 1362 (9.5) | 585 (42.9) | 691 (50.7) | 745 (54.7) | 863 (63.4) |

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASL TO4 | AUSL VdA | ASL TO4 | AUSL VdA | ASL TO4 | AUSL VdA | ASL TO4 | AUSL VdA | |

| Rank 1 | PPI | PPI | PPI | PPI | PPI | PPI | PPI | PPI |

| Patients (%) | 86.5 | 86.6 | 87.9 | 88.1 | 88.6 | 88.9 | 88.3 | 88.0 |

| Rank 2 | Paro | SU | Paro | SU | Paro | Paro | Paro | Paro |

| Patients (%) | 8.3 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 7.6 | 5.3 | 7.9 | 5.6 |

| Rank 3 | SU | Paro | SU | Paro | NSAID | SU | Amio | SU |

| Patients (%) | 3.6 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 4.9 |

| Rank 4 | NSAID | Amio | NSAID | Amio | SU | Amio | TCA | Amio |

| Patients (%) | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 3.4 |

| Rank 5 | TCA | NSAID | TCA | TCA | TCA | TCA | NSAID | TCA |

| Patients (%) | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| Rank 6 | - | TCA | - | NSAID | - | - | - | - |

| Patients (%) | - | 2.5 | - | 2.3 | - | - | - | - |

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TO4 | VdA | TO4 | VdA | TO4 | VdA | TO4 | VdA | |

| Rank 1 | Furo | Furo | Furo | Furo | Furo | Furo | Furo | Furo |

| Patients (%) | 53.4 | 50.4 | 57.7 | 53.6 | 59.1 | 55.1 | 60.8 | 56.1 |

| Rank 2 | M diu ass | Aldo | M diu ass | Aldo | Aldo | Aldo | Aldo | Aldo |

| Patients (%) | 17.0 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 16.4 | 14.0 | 17.1 | 14.8 | 20.1 |

| Rank 3 | Aldo | Tra | Aldo | Tra | M diu ass | Tra | M diu ass | Tra |

| Patients (%) | 11.7 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 9.9 | 11.2 |

| Rank 4 | Tra | M diu ass | M diu | M diu ass | Tra | Mirta | Tra | Mirta |

| Patients (%) | 9.5 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| Rank 5 | M diu | Mirta | Tra | Mirta | M diu | M diu ass | Furo ass | Antip |

| Patients (%) | 6.6 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.4 |

| Rank 6 | Furo ass | Hydro | Furo ass | Hydro | Furo ass | Antip | M diu | M diu ass |

| Patients (%) | 5.8 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 5.9 |

| Total, n (%) | 2368 |

| Males, n (%) | 630 (26.6) |

| Age, median [IQR] | 75.0 [70.0–81.0] |

| Age range, n (%) | |

| 65–74 years | 1088 (45.9) |

| 75–84 years | 985 (41.6) |

| ≥85 years | 295 (12.5) |

| Dispensations of chronic anticholinergics per patient, median [IQR] | 6 [6–8] |

| Frequency of chronic anticholinergics, n (%) | |

| Antidepressants | 1975 (83.4) |

| Antipsychotics | 297 (12.5) |

| Drugs for urinary frequency and incontinence | 176 (7.4) |

| Trihexyphenidyl | 5 (<1) |

| Disopyramide | 2 (<1) |

| Hydroxyzine | 1 (<1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armando, L.G.; Luboz, J.; Diarassouba, A.; Miglio, G.; Cena, C. Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Drug Dispensing Data of Older Adults Living in Northwest Italy. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060184

Armando LG, Luboz J, Diarassouba A, Miglio G, Cena C. Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Drug Dispensing Data of Older Adults Living in Northwest Italy. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060184

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmando, Lucrezia Greta, Jacopo Luboz, Abdoulaye Diarassouba, Gianluca Miglio, and Clara Cena. 2025. "Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Drug Dispensing Data of Older Adults Living in Northwest Italy" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060184

APA StyleArmando, L. G., Luboz, J., Diarassouba, A., Miglio, G., & Cena, C. (2025). Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Drug Dispensing Data of Older Adults Living in Northwest Italy. Pharmacy, 13(6), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060184