Mining of Adverse Event Signals Associated with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Triple Therapy: A Post-Marketing Analysis Based on FAERS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

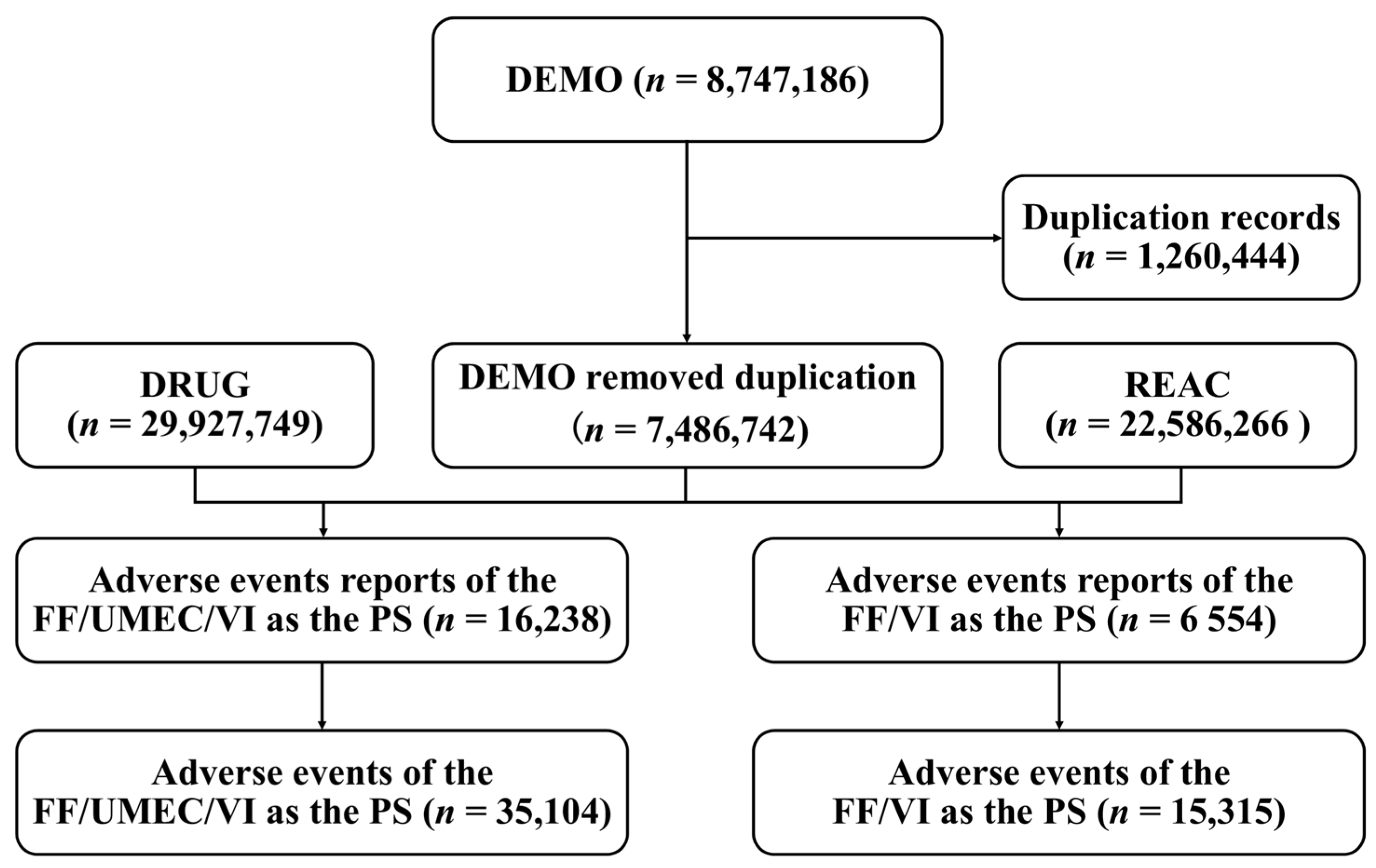

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

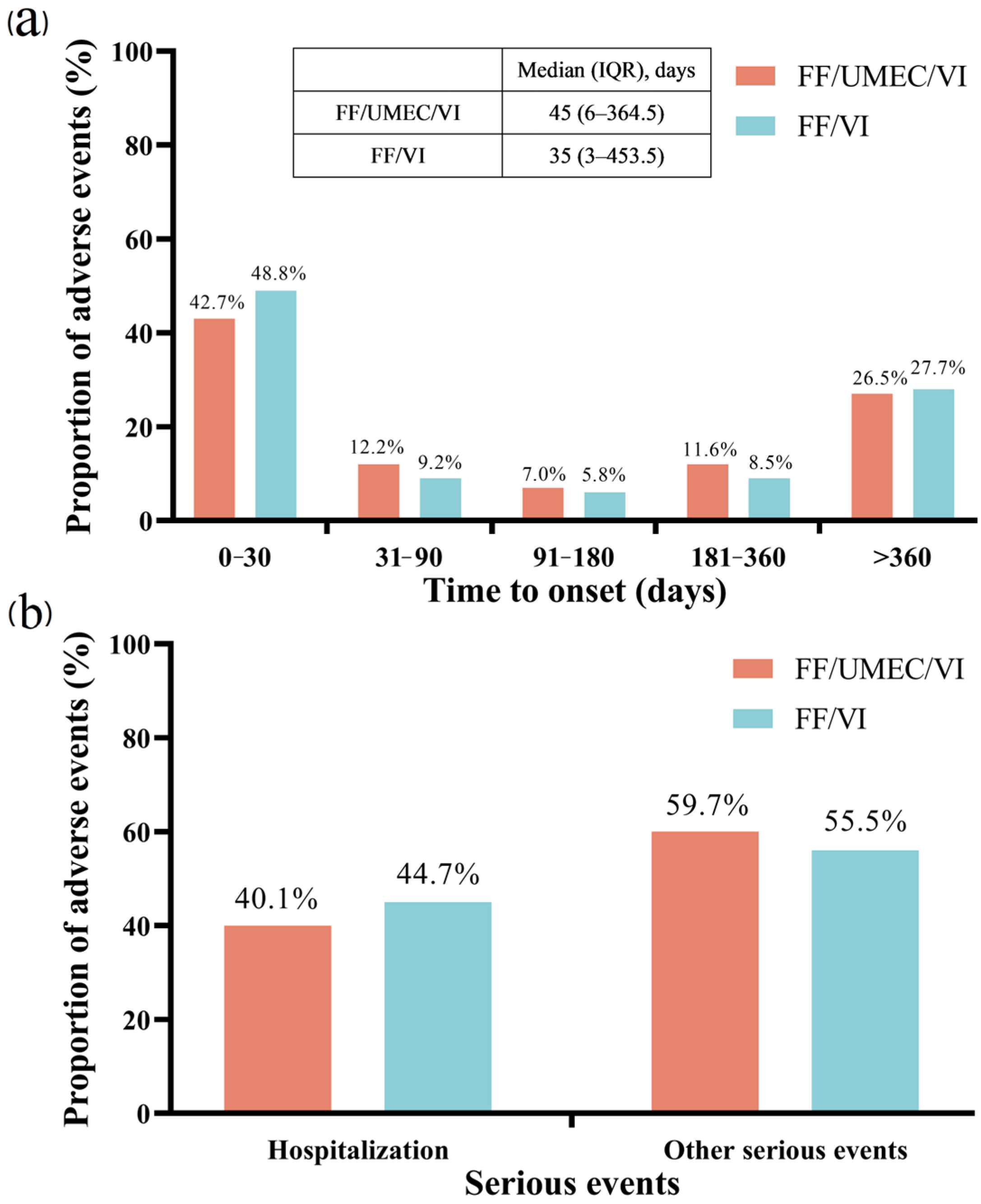

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. System Organ Class Disproportionality Analysis

3.3. Preferred Terms Disproportionality Analysis

3.4. The Comparison Among FF/UMEC/VI and FF/VI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Adverse Event |

| ARR | Absolute Risk Reduction |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| DEMO | Demographic/administrative file |

| DRUG | Drug information file |

| EBGM | Empirical Bayesian Geometric Mean |

| FAERS | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s |

| FF | Fluticasone Furoate |

| IC | Information Component |

| ICS | Inhaled Corticosteroid |

| IQR | Inter Quartile Range |

| LABA | Long-Acting Beta2 Agonist |

| LAMA | Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist |

| MedDRA | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities |

| PRR | Proportional Reporting Ratio |

| PT | Preferred Term |

| PS | Primary Suspect |

| REAC | Reaction file |

| ROR | Reporting Odds Ratio |

| SOC | System Organ Class |

| SGRQ | St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire |

| TTO | Time-To-Onset |

| UMEC | Umeclidinium |

| VI | Vilanterol |

References

- Ferrera, M.C.; Labaki, W.W.; Han, M.K. Advances in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2021, 72, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S.A.; Smith, B.M.; Bafadhel, M.; Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liang, H.; Wei, L.; Shi, D.; Su, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Health inequality in the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2022, 17, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranmer, J.; Rotter, T.; O’Donnell, D.; Marciniuk, D.; Green, M.; Kinsman, L.; Li, W. Determining the influence of the primary and specialist network of care on patient and system outcomes among patients with a new diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, S.; Conde, B.; Fragoso, E.; Boléo-Tomé, J.P.; Areias, V.; Cardoso, J. COPD and cardiovascular disease. Pulmonology 2019, 25, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, Y.; Su, K.; Chen, H.; Li, F.; Hukportie, D.N.; Niu, F.; Yiu, K.; Wu, X. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in relationship to cardiovascular outcomes. Chest 2023, 163, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnert, K.; Jörres, R.A.; Behr, J.; Welte, T. The diagnosis and treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzetta, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M. Pharmacological interaction between LABAs and LAMAs in the airways: Optimizing synergy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 761, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Campos, J.L.; Carrasco-Hernandez, L.; Quintana-Gallego, E.; Calero-Acuña, C.; Márquez-Martín, E.; Ortega-Ruiz, F.; Soriano, J.B. Triple therapy for COPD: A crude analysis from a systematic review of the evidence. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2019, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, S.; Snowise, N.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Midwinter, D.; Ismaila, A.S.; Irving, E.; Sansbury, L.; Tabberer, M.; Leather, D.; Compton, C. Clinical effectiveness of once-daily fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in usual practice: The COPD INTREPID study design. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00061-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaila, A.S.; Haeussler, K.; Czira, A.; Youn, J.-H.; Malmenäs, M.; Risebrough, N.A.; Agarwal, J.; Nassim, M.; Sharma, R.; Compton, C.; et al. Fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) triple therapy compared with other therapies for the treatment of COPD: A network meta-analysis. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 3957–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeh, K.-M.; Scheithe, K.; Schmutzler, H.; Krüger, S. Real-world effectiveness of fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy for symptomatic COPD: The ELLITHE non-interventional trial. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2024, 19, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; Anderson, M.; Anzueto, A.; Brown, N.; Compton, C.; Corbridge, T.C.; Erb, D.; Harvey, C.; Kaisermann, M.C.; Kaye, M.; et al. Single-inhaler fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) triple therapy versus tiotropium monotherapy in patients with COPD. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2021, 31, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, B.; Yu, J. Adverse event signal mining and severe adverse event influencing factor analysis of Lumateperone based on FAERS database. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1472648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaeda, T.; Tamon, A.; Kadoyama, K.; Okuno, Y. Data Mining of the Public Version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.; Shen, G.; Jia, X. Mining of adverse event signals associated with inclisiran: A post-marketing analysis based on FAERS. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 24, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, G.; Emmanuel, B.; Ariti, C.; Bafadhel, M.; Papi, A.; Carter, V.; Zhou, J.; Skinner, D.; Xu, X.; Müllerová, H.; et al. A long-term study of adverse outcomes associated with oral corticosteroid use in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 2565–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Barnhart, F.; Brealey, N.; Brooks, J.; Criner, G.J.; Day, N.C.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Jones, C.E.; et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.T.; Brown, N.; Compton, C.; Corbridge, T.C.; Dorais, K.; Fogarty, C.; Harvey, C.; Kaisermann, M.C.; Lipson, D.A.; Martin, N.; et al. Once-daily single-inhaler versus twice-daily multiple-inhaler triple therapy in patients with COPD: Lung function and health status results from two replicate randomized controlled trials. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, K.; Harada, N.; Horiuchi, A.; Umemoto, S.; Kurabatashi, R.; Yui, A.; Yamamura, H.; Shinka, Y.; Miyao, N. Therapeutic response to single-inhaler triple therapies in moderate-to-severe COPD. Respir. Care 2023, 68, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Barnacle, H.; Birk, R.; Brealey, N.; Locantore, N.; Lomas, D.A.; Ludwig-Sengpiel, A.; Mohindra, R.; Tabberer, M.; Zhu, C.-Q.; et al. FULFIL trial: Once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, S.; Barnes, N.; Brusselle, G.; Compton, C.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Hartley, B.; Lange, P.; et al. Blood eosinophils and treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Analysis of the IMPACT trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.J.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Lipson, D.A.; Maghzal, G.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Midwinter, D.; Singh, D.; et al. Effect of chronic mucus hypersecretion on treatment responses to inhaled therapies in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Post hoc analysis of the IMPACT trial. Respirology 2022, 27, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, E.; Martin, A.; Schroeder, M.; Mealing, S.J.; Solanke, O.; Risebrough, N.; Ismaila, A.S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a single-inhaler triple therapy for COPD in the UK. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00480–02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Ye, M.; Park, J.; Geum, S. Immunopathologic role of eosinophils in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Suzuki, M.; Kato, Y.; Kidoguchi, M.; Kumai, T.; Fujieda, S.; Sakashita, M. The current findings in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2024, 51, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Hussein, M.T.; Emam, A.M.; Rashad, U.M.; Rezk, I.; Awad, A.H. Is insufficient pulmonary air support the cause of dysphonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Auris Nasus Larynx 2018, 45, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naunheim, M.R.; Huston, M.N.; Bhattacharyya, N. Voice disorders associated with the use of inhaled corticosteroids. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartford, C.G.; Petchel, K.S.; Mickail, H.; Perez-Gutthann, S.; McHale, M.; Grana, J.M.; Marquez, P. Pharmacovigilance during the pre-approval phases: An evolving pharmaceutical industry model in response to ICH E2E, CIOMS VI, FDA and EMEA/CHMP risk-management guidelines. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, D.; Parakh, A. Fluticasone furoate: A new intranasal corticosteroid. J. Postgrad. Med. 2012, 58, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempsford, R.; Norris, V.; Siederer, S. Vilanterol trifenatate, a novel inhaled long-acting beta2 adrenoceptor agonist, is well tolerated in healthy subjects and demonstrates prolonged bronchodilation in subjects with asthma and COPD. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, K.S.; Morjaria, J.B. Umeclidinium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2017, 8, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogart, M.; Germain, G.; Laliberté, F.; Mahendran, M.; Duh, M.S.; DiRocco, K.; Noorduyn, S.G.; Paczkowski, R.; Balkissoon, R. Real-world study of single-inhaler triple therapy with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol on asthma control in the US. J. Asthma Allergy 2023, 16, 1309–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozawa, S.; Ohbayashi, H.; Tsuchiya, M.; Hara, Y.; Lee, L.A.; Nakayama, T.; Tamaoki, J.; Fowler, A.; Nishi, T. Safety of once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in Japanese patients with asthma: A long-term (52-week) phase III open-label study. J. Asthma Allergy 2021, 14, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | FF/UMEC/VI | FF/VI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16,238 | 6554 | |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 4948 (30.47) | 1881 (28.70) | |

| Male | 7484 (46.09) | 3895 (59.43) | |

| Missing | 3806 (23.44) | 778 (11.87) | |

| Age (year), n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| <18 | 22 (0.14) | 19 (0.29) | |

| 18≤ and <65 | 887 (5.46) | 590 (9.00) | |

| ≥65 | 2847 (17.53) | 1090 (16.63) | |

| Missing | 12,482 (76.87) | 4855 (74.08) | |

| Median (IQR) | 72 (65, 79) | 70 (60, 78) | |

| Reporting country, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| United States | 14,636 (90.13) | 6489 (99.01) | |

| Non-United States | 1602 (9.87%) | 65 (0.99) | |

| Reporter, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Consumer | 13,964 (86.00) | 6085 (92.84) | |

| Health professional | 786 (4.84) | 162 (2.47) | |

| Physician | 1001 (6.16) | 163 (2.49) | |

| Pharmacist | 444 (2.73) | 131 (2.00) | |

| Missing | 43 (0.26) | 33 (0.50) | |

| Reporting year, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 2019 | 891 (5.49) | 1185 (18.08) | |

| 2020 | 2702 (16.64) | 1299 (19.82) | |

| 2021 | 2911 (17.93) | 549 (8.38) | |

| 2022 | 3479 (21.43) | 954 (14.56) | |

| 2023 | 3461 (21.31) | 1890 (28.84) | |

| 2024 | 2794 (17.21) | 677 (10.33) | |

| SOC | n | ROR (95% CI) | IC (IC025) | EBGM (EBGM05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 9067 | 2.46 (2.40, 2.52) | 2.08 (5810.78) | 1.06 (1.02) | 2.08 (2.04) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 6567 | 4.87 (4.74, 5.00) | 4.15 (16,324.16) | 2.05 (2.01) | 4.13 (4.04) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 5215 | 0.81 (0.79, 0.83) | 0.84 (198.86) | 0.26 (0.3) | 0.84 (0.82) |

| Infections and infestations | 2142 | 1.09 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (13.49) | 0.11 (0.05) | 1.08 (1.04) |

| Product issues | 1915 | 2.98 (2.84, 3.12) | 2.87 (2367.56) | 1.52 (1.45) | 2.86 (2.75) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1547 | 0.54 (0.51, 0.57) | 0.56 (573.31) | 0.83 (0.91) | 0.56 (0.54) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1439 | 0.54 (0.52, 0.57) | 0.56 (526.82) | 0.83 (0.91) | 0.56 (0.54) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 1210 | 2.36 (2.23, 2.50) | 2.31 (913.40) | 1.21 (1.12) | 2.31 (2.20) |

| Investigations | 804 | 0.38 (0.35, 0.41) | 0.39 (796.60) | 1.34 (1.45) | 0.39 (0.37) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 776 | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | 0.43 (611.29) | 1.21 (1.32) | 0.43 (0.41) |

| Eye disorders | 666 | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.45) | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.97 (0.91) |

| Cardiac disorders | 649 | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.95 (1.86) | 0.08 (0.19) | 0.95 (0.89) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 549 | 0.28 (0.26, 0.30) | 0.29 (999.66) | 1.78 (1.90) | 0.29 (0.27) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 533 | 0.82 (0.75, 0.89) | 0.82 (21.45) | 0.29 (0.41) | 0.82 (0.76) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) | 518 | 0.37 (0.34, 0.41) | 0.38 (533.60) | 1.38 (1.51) | 0.38 (0.36) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 467 | 0.23 (0.21, 0.26) | 0.24 (1156.84) | 2.03 (2.17) | 0.24 (0.23) |

| Vascular disorders | 241 | 0.37 (0.32, 0.42) | 0.37 (259.96) | 1.42 (1.61) | 0.37 (0.34) |

| Immune system disorders | 193 | 0.47 (0.41, 0.55) | 0.48 (112.15) | 1.07 (1.28) | 0.48 (0.42) |

| Social circumstances | 190 | 1.13 (0.98, 1.31) | 1.13 (2.99) | 0.18 (0.03) | 1.13 (1.01) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 169 | 0.25 (0.21, 0.29) | 0.25 (386.34) | 2.00 (2.22) | 0.25 (0.22) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 92 | 0.64 (0.52, 0.78) | 0.64 (18.71) | 0.64 (0.94) | 0.64 (0.54) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 59 | 0.28 (0.22, 0.36) | 0.28 (109.82) | 1.83 (2.21) | 0.28 (0.23) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 46 | 0.07 (0.06, 0.10) | 0.08 (525.00) | 3.71 (4.14) | 0.08 (0.06) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 23 | 0.08 (0.05, 0.12) | 0.08 (249.66) | 3.66 (4.25) | 0.08 (0.06) |

| Endocrine disorders | 23 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.37) | 0.25 (53.21) | 2.02 (2.61) | 0.25 (0.18) |

| SOC | PT | n | ROR (95% CI) | IC (IC025) | EBGM (EBGM05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | Chronic eosinophilic rhinosinusitis | 3 | 96.32 (28.62, 324.16) | 96.31 (246.06) | 6.39 (4.83) | 83.88 (30.39) |

| Bronchospasm paradoxical | 5 | 50.97 (20.5, 126.71) | 50.96 (226.89) | 5.56 (4.34) | 47.29 (22.07) | |

| Dysphonia | 639 | 21.07 (19.46, 22.81) | 20.71 (11,620.28) | 4.33 (4.21) | 20.09 (18.8) | |

| Vocal cord dysfunction | 9 | 16.71 (8.62, 32.38) | 16.70 (129.49) | 4.03 (3.1) | 16.3 (9.37) | |

| Paranasal sinus inflammation | 4 | 16.36 (6.06, 44.14) | 16.36 (56.25) | 4 (2.69) | 15.98 (6.96) | |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | Foreign body in mouth | 5 | 48.65 (19.6, 120.76) | 48.64 (216.89) | 45.29 (21.16) | 5.5 (4.27) |

| Infections and infestations | Oropharyngeal candidiasis | 14 | 30.9 (18.07, 52.84) | 30.89 (386.34) | 29.52 (18.84) | 4.88 (4.12) |

| Candida infection | 264 | 24.86 (21.97, 28.12) | 24.68 (5777.46) | 23.8 (21.47) | 4.57 (4.39) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Coating in mouth | 10 | 29.46 (15.63, 55.54) | 29.45 (262.82) | 4.82 (3.93) | 28.21 (16.59) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | Urine flow decreased | 17 | 19.68 (12.14, 31.89) | 19.67 (292.27) | 4.26 (3.57) | 19.11 (12.76) |

| SOC | PT | n | ROR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal and urinary disorders | Urinary retention | 157 | 8.60 (4.22, 17.50) | 8.56 (51.01) |

| Bronchospasm paradoxical | 93 | 6.78 (2.97, 15.48) | 6.76 (27.73) | |

| Pollakiuria | 55 | 2.67(1.32, 5.40) | 2.67 (8.06) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Lip swelling | 30 | 2.62 (1.02, 6.75) | 2.62 (4.29) |

| Constipation | 84 | 3.34 (1.78, 6.26) | 3.33 (15.90) | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 49 | 2.38 (1.17, 4.84) | 2.38 (6.06) | |

| Investigations | Blood pressure decreased | 18 | 7.86 (1.05, 58.86) | 7.85 (5.67) |

| Nervous system disorders | Taste disorder | 63 | 3.06 (1.52, 6.15) | 3.05 (10.89) |

| Eye disorders | Vision blurred | 145 | 3.02 (1.91, 4.78) | 3.01 (24.74) |

| Infections and infestations | Urinary tract infection | 74 | 2.15 (1.24, 3.75) | 2.15 (7.71) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Qiao, Y.; Qiao, G.; Jia, X.; Zhu, J. Mining of Adverse Event Signals Associated with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Triple Therapy: A Post-Marketing Analysis Based on FAERS. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060178

Chen J, Qiao Y, Qiao G, Jia X, Zhu J. Mining of Adverse Event Signals Associated with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Triple Therapy: A Post-Marketing Analysis Based on FAERS. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060178

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiajun, Ying Qiao, Gaoxing Qiao, Xiaocan Jia, and Jicun Zhu. 2025. "Mining of Adverse Event Signals Associated with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Triple Therapy: A Post-Marketing Analysis Based on FAERS" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060178

APA StyleChen, J., Qiao, Y., Qiao, G., Jia, X., & Zhu, J. (2025). Mining of Adverse Event Signals Associated with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Triple Therapy: A Post-Marketing Analysis Based on FAERS. Pharmacy, 13(6), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060178