Assessment of Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit Job Among Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

3.2. Personal Professional Experience

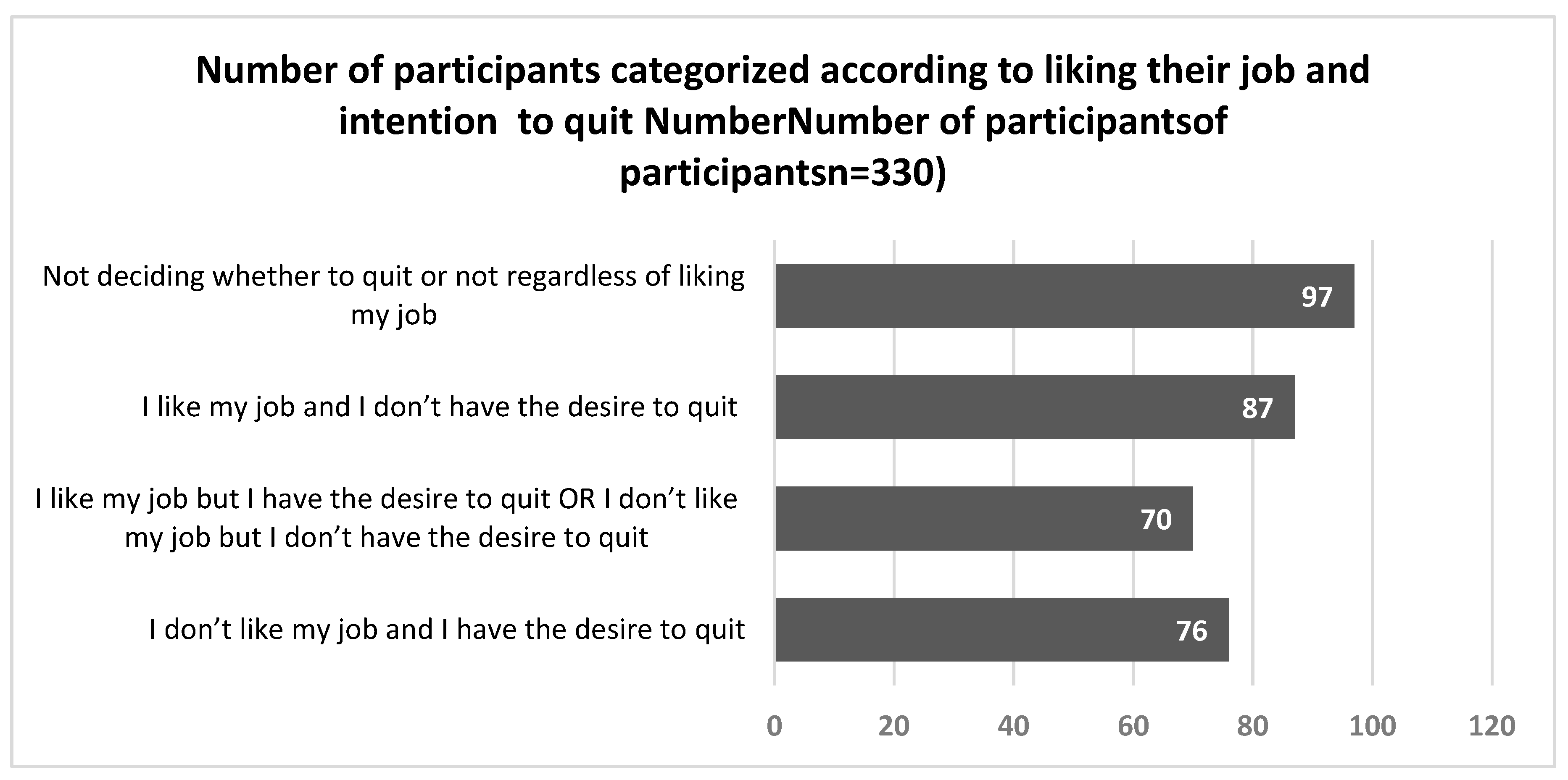

3.3. Current Job Satisfaction and Desire to Quit

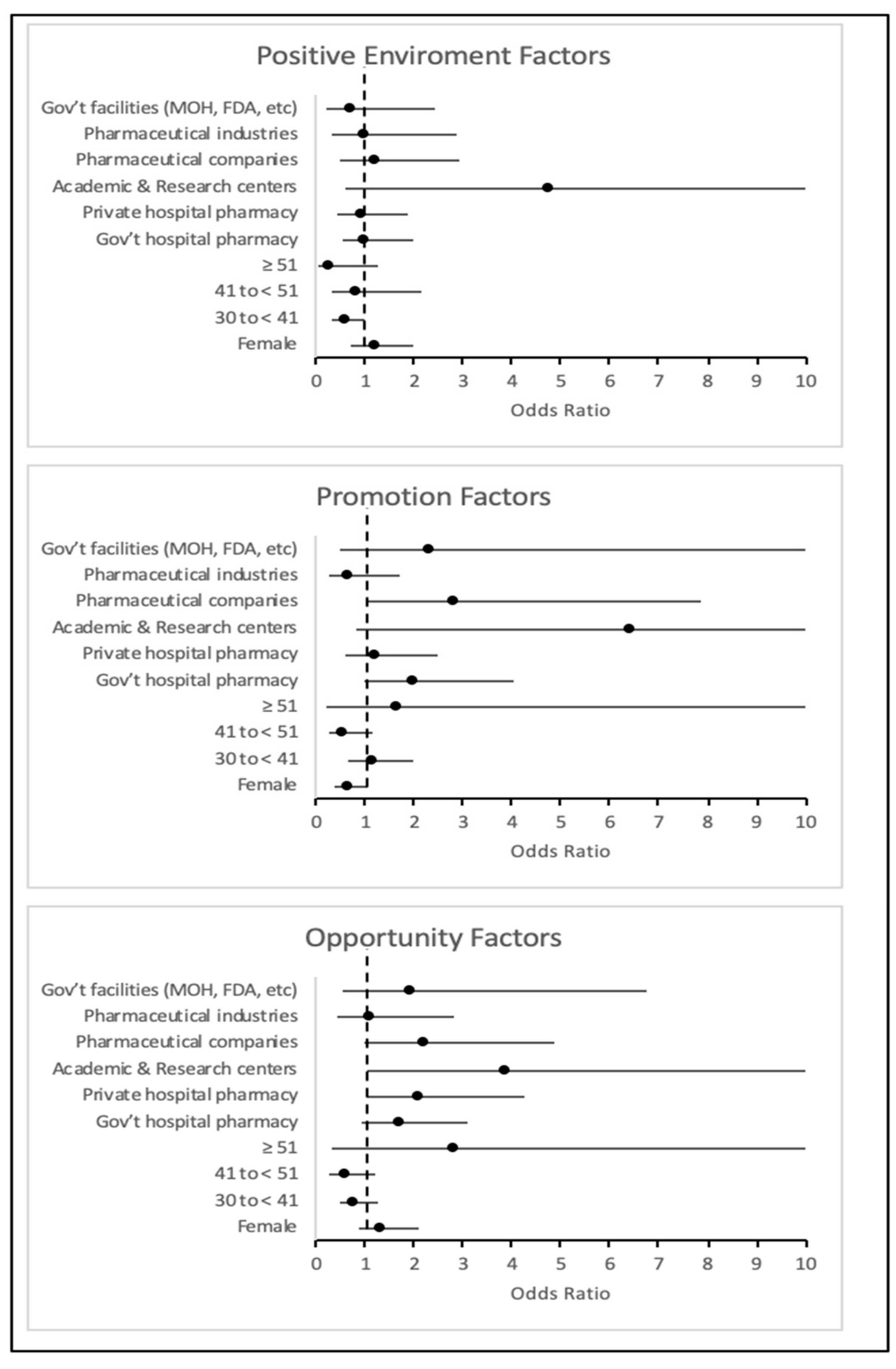

3.4. Job Satisfaction Factors and Motivational Methods

3.5. Levels of Job Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAR | Saudi Riyals (Saudi Currency) |

| Pharm.B. | Bachelor of Pharmacy |

| Pharm.D. | Doctor of Pharmacy |

| MOH | Ministry of Health |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Alhaqqas, N.H.; Sulaiman, A.A. Job Satisfaction and Associated Factors Among Primary Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study From Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e62969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albugami, H.; Albagmi, S.; Alqahtani, M.; Alharbi, N.L. Healthcare Professionals’ Job Satisfaction at Primary Healthcare Centers in The Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Salud Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2024, 4, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.H.M.; Alotaibi, A.H.M.; Alotaibi, A.M.H.; Alwahbi, E.B.; Alkhathlan, M.S.; Alnaddah, S.M.; Alotaibi, M.M.; Haighton, K. Job Satisfaction among Primary Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia and Associated Factors: A Systematic Review. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Open Access 2022, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawani, L.A.; Halawani, M.A.; Beyari, G.M. Job satisfaction among Saudi healthcare workers and its impact on the quality of health services. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.-A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees—Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R. The Impact of Employees’ Health and Well-being on Job Performance. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 29, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, A.; Isouard, G. Job Satisfaction and Retention of Nursing Staff in Saudi Hospitals. Asia-Pac. J. Health Manag. 2019, 14, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T. Job Satisfaction and Job Performance, A Study on Colleges of Saudi Arabia. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2014, 3, 2972–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarfi, R.F.; Bakhsh, A.M.A.; Alghamdi, I.D.; Alotaibi, F.A. Revealing the relation between job satisfaction and workload: A cross-sectional study in the emergency department. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selebi, C.; Minnaar, A. Job satisfaction among nurses in a public hospital in Gauteng. Curationis 2007, 30, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suji, U.; Nandhini, N. A STUDY ON JOB SATISFACTION AMONG EMPLOYEES IN ONE OF THE MULTI-SPECIALITY HOSPITAL. EPRA Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2021, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.K.; Khayat, R. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment Among Hospital Staff: A Systematic Review. J. Health Manag. 2021, 23, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, W. Employee Motivation and Its Impact on Productivity in the Case of National Alcohol and Liquor Factory (NALF). Int. J. Law Policy 2015, 15, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, A. Effects of Motivation on Staff Performance and Job Satisfaction in The University of Ilorin Library. Insa. J. Islam Humanit. 2021, 5, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Yücel, İ.; Gomes, D. How Transformational Leadership predicts Employees’ Affective Commitment and Performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1901–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Kaur, M.; Verma, M.; Kumar, R. Job satisfaction among health care providers: A cross-sectional study in public health facilities of Punjab, India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3268–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, M.; Maimani, K.; Kassim, N.M. A comparative study on job satisfaction between registered nurses and other qualified healthcare professionals. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 10, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cooper-Thomas, H.; Anderson, N.; Bliese, P. The Power of Momentum: A New Model of Dynamic Relationships Between Job Satisfaction Change and Turnover Intentions. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumaili, A.A.; Sherbeny, F.; Elhiny, R.; Hijazi, B.; Elbarbry, F.; Rahal, M.; Bukhatwa, S.; Khdour, M.; Thomas, D.; Khalifa, S.; et al. Exploring job satisfaction among pharmacy professionals in the Arab world: A multi-country study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 30, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Khan, W.; Daraz, U.; Hussain, M.; Alam, H.; Khyber, P.; Pakistan. Assessing the Consequential Role of Infrastructural Facilities in Academic Performance of Students in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2013, 3, 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaiji, L.; Al-jedai, A.; Alamri, A.; Alshehri, A.M.; Alqazlan, N.; Almogbel, Y. Effect of Occupational Stress on Pharmacists’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaznai, M.; Almadani, O.; Aloraifi, I.; Alsallouk, S.; Alkabaz, H.; Alotaibi, A.; Alamri, H.; Al-Hennawi, K.; Al-Hennawi, M.; Alomi, Y. Assessment of Patient Satisfaction with Pharmaceutical Services in Ministry of Health Hospitals at East Province, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Sci. 2019, 8, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, V.S.L.; March, G.J.; Clark, A.; Gilbert, A.L. Why do Australian registered pharmacists leave the profession? a qualitative study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012, 35, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A. Stress and job satisfaction among pharmacists in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, S.A. Job satisfaction in Saudi community pharmacists [12]. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2005, 35, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muallem, N.; Al-Surimi, K. Job satisfaction, work commitment and intention to leave among pharmacists: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkhi, B.; Alghamdi, A.; Alshehri, N.; Alshehri, A. Assessment of job satisfaction among hospital pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. IOSR J. Pharm. 2017, 7, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.; Proença, T. Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and validation in a population of portuguese hospital workers. Investig. E Interv. Em Recur. Hum. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tasios, T.; Giannouli, V. Job Descriptive Index (JDI): Reliability and validity study in Greece. Arch. Assess. Psychol. 2011, 7, 31–61. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tremblay, M.; Blanchard, C.; Taylor, S.; Pelletier, L.; Villeneuve, M. Work Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Scale: Its Value for Organizational Psychology Research. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2009, 41, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherecheș, M.C.; Finta, H.; Prisada, R.M.; Rusu, A. Pharmacists’ Professional Satisfaction and Challenges: A Netnographic Analysis of Reddit and Facebook Discussions. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jegede, A.; Olabanji, K.; Sorinola, O.; Erhun, W. Exploring the demographics, educational qualifications, and remunerations of pharmacists in diverse practice settings in Nigeria. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2025, 24, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, E.; Ronis, K. Assessment of Job Satisfaction Among Registered Pharmacists Working in Public and Private Hospitals of Multan. Pak. J. Public Health 2016, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alomi, Y.; Bahadig, F.; Shahzad, K.; Qaism, S.; Aloumi, B.; Alghuraybi, B.; Alsubaie, R. Stress Factors Impact on Pharmacist Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Biomed. Rep. 2019, 5, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Naqvi, A.A. Which aspects of job determine satisfaction among pharmacists working in Saudi pharmacy settings? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, D.; Acquisto, N.; Buckley, M.; Erdman, G.; Kerns, S.; Nwaesei, A.; Szymanski, T.; Walkerly, A.; Yau, A.; Martello, J. Rewards, Recognition, and Advancement for Clinical Pharmacists. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2023, 6, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, B.; Nikolaev, B.; Shepherd, D. Does Educational Attainment Promote Job Satisfaction? The Bittersweet Trade-offs Between Job Resources, Demands, and Stress. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 107, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolina, V.; Novokreshchenova, I.; Novokreshchenov, I. Job Satisfaction Among Pharmacists. Russ. Open Med. J. 2021, 10, e0313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, Y.; Hawulte, B.; Feto, T.; Basker, G.V.; Bacha, Y.D. Job satisfaction among pharmacy professionals working in public hospitals and its associated factors, eastern Ethiopia. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.H.; Misbah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Mehboob, T.; Bashir, I. Quantifying satisfaction among pharmacists working in Pharmaceutical Sales or Marketing and its inferential relationship with demographics: A Cross-Sectional analysis in Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, L.; Hughes, C.M.; Adair, C.G.; Cardwell, C. Assessing job satisfaction and stress among pharmacists in Northern Ireland. Pharm. World Sci. 2009, 31, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.J.; Lynd, L.D.; Marra, C.A. Pharmacists’ Satisfaction with Work and Working Conditions in New Zealand—An Updated Survey and a Comparison to Canada. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omar, H.A.; Khurshid, F.; Sayed, S.K.; Alotaibi, W.H.; Almutairi, R.M.; Arafah, A.M.; Mansy, W.; Alshathry, S. Job Motivation and Satisfaction Among Female Pharmacists Working in Private Pharmacy Professional Sectors in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teong, W.W.; Ng, Y.K.; Paraidathathu, T.; Chong, W.W. Job satisfaction and stress levels among community pharmacists in Malaysia. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2019, 49, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zabir, A.; Nur Mozahid, M.; Bhuiyan, M.; Lima, R.; Tasnim, A. Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction of Women Employees in Public and Private Sectors in Sylhet City, Bangladesh. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjing, G.; Chupradit, S.; Ku, K.Y.; Nassani, A.A.; Haffar, M. Impact of Employees’ Workplace Environment on Employees’ Performance: A Multi-Mediation Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 890400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants’ Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 189 (57.3) |

| Female | 141 (42.7) |

| Age (years) | |

| 24 to <30 | 158 (47.9) |

| 30 to <41 | 135 (40.9) |

| 41 to <51 | 31 (9.4) |

| ≥51 | 6 (1.8) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 256 (77.6) |

| Non-Saudi | 74 (22.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 162 (49.1) |

| Married | 154 (46.7) |

| Divorced | 13 (3.9) |

| Widow | 1 (0.3) |

| Region | |

| Central | 171 (51.8) |

| East | 40 (12.1) |

| West | 70 (21.1) |

| South | 33 (10.0) |

| North | 16 (4.8) |

| Highest qualification | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.1) |

| Pharm.B. or undergraduate | 41 (12.4) |

| Pharm.D. | 185 (56.1) |

| Master | 56 (17.0) |

| Residency/fellow | 26 (7.9) |

| Ph.D. | 15 (4.5) |

| Current position | |

| Administrative work | 32 (9.7) |

| Senior staff [supervisor] | 38 (11.5) |

| Staff/employee | 226 (68.5) |

| Training unit or work | 14 (4.2) |

| Research | 14 (4.2) |

| Others | 6 (1.8) |

| Organization type | |

| Retail or community pharmacy | 118 (35.8) |

| Governmental hospital pharmacy | 75 (22.7) |

| Private hospital pharmacy | 51 (15.5) |

| Academic and research centers | 15 (4.5) |

| Pharmaceutical companies | 36 (10.9) |

| Pharmaceutical industries | 19 (5.8) |

| Governmental facilities such as MOH or FDA | 12 (3.6) |

| Others | 4 (1.2) |

| Monthly income (SAR) | |

| ≤9000 | 150 (45.5) |

| >9100 to 15,000 | 98 (29.7) |

| >15,000 to 21,000 | 43 (13) |

| >21,000 | 39 (11.8) |

| Professional experience (years) | |

| ≤5 | 189 (57.3) |

| >5 to 15 | 105 (31.8) |

| >15 to 20 | 20 (6.1) |

| >20 | 16 (4.8) |

| Currently working as a practicing pharmacist | |

| Yes | 273 (82.7) |

| No | 57 (17.3) |

| Participants’ Professional Experience | N (%) |

|---|---|

| (a) Objective professional personnel experience | |

| Average working hours per week | |

| <30 | 15 (4.5) |

| 30–39 | 27 (8.2) |

| 40–48 | 151 (45.8) |

| >48 | 137 (41.5) |

| Tasks to do in 4 h per day at work | |

| 1 task | 14 (4.2) |

| 2 tasks | 45 (13.6) |

| 3 tasks | 70 (21.2) |

| ≥4 tasks | 201 (60.9) |

| Work in a shift system | |

| Yes | 197 (59.7) |

| No | 133 (40.3) |

| Work as teams or as individuals at work | |

| Teamwork | 79 (23.9) |

| Individual work | 45 (13.6) |

| Both | 206 (62.4) |

| (b) Subjective professional personnel experience | |

| Earning enough money | |

| Yes | 99 (30.0) |

| No | 231 (70.0) |

| Feeling rewarded for efforts | |

| Yes | 110 (33.3) |

| No | 220 (66.7) |

| Feeling of personal accomplishment and satisfaction at work | |

| Yes | 135 (40.9) |

| No | 88 (26.7) |

| Maybe | 107 (32.4) |

| Institution provides opportunities for personal career growth and development | |

| Yes | 128 (38.8) |

| No | 202 (61.2) |

| Thinking to work for the same institution in the next 5 years | |

| Yes | 71 (21.5) |

| No | 141 (42.7) |

| Maybe | 118 (35.8) |

| I Don’t Like My Job and I Have the Desire to Quit (n = 76) | I Like My Job but I Have the Desire to Quit OR I Don’t Like My Job but I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 70) | I Like My Job and I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 87) | Not Decided Whether to Quit or Not Regardless of Liking My Job (n = 97) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Demographic variables | |||||

| Gender | 0.504 | ||||

| Male | 43 (22.8) | 42 (22.2) | 54 (28.6) | 50 (26.5) | |

| Female | 33 (23.4) | 28 (19.9) | 33 (23.4) | 47 (33.3) | |

| Age (yrs) | 0.228 | ||||

| 24 to <30 | 45 (28.5) | 35 (22.2) | 37 (23.4) | 41 (25.9) | |

| 30 to <41 | 25 (18.5) | 29 (21.5) | 36 (26.7) | 45 (33.3) | |

| 41 to <51 | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 13 (41.9) | 10 (32.3) | |

| ≥51 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Nationality | 0.070 | ||||

| Saudi | 66 (25.8) | 56 (21.9) | 61 (23.8) | 73 (28.5) | |

| Non-Saudi | 10 (13.5) | 14 (18.9) | 26 (35.1) | 24 (32.4) | |

| Marital status | 0.028 | ||||

| Single | 46 (28.4) | 32 (19.8) | 43 (26.5) | 41 (25.3) | |

| Married | 28 (18.2) | 36 (23.4) | 44 (28.6) | 46 (29.9) | |

| Divorced | 2 (15.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Widow | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | |

| Region | 0.591 | ||||

| Central | 38 (22.2) | 34 (19.9) | 48 (28.1) | 51 (29.8) | |

| East | 11 (27.5) | 7 (17.5) | 8 (20.0) | 14 (35.0) | |

| West | 18 (25.7) | 15 (21.4) | 19 (27.1) | 18 (25.7) | |

| South | 9 (27.3) | 10 (30.0) | 7 (21.2) | 7 (21.2) | |

| North | 0 (0.0) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Highest qualification | 0.035 | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (14.3) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pharm.B or undergraduate | 15 (36.6) | 10 (24.4) | 6 (14.6) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Pharm.D. | 45 (24.3) | 42 (22.7) | 46 (24.9) | 52 (28.1) | |

| Master | 10 (17.9) | 6 (10.7) | 17 (30.4) | 23 (41.1) | |

| Residency/Fellow | 3 (11.5) | 4 (15.4) | 12 (46.2) | 7 (26.9) | |

| Ph.D. | 2 (13.3) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (33.3) | |

| (b) Professional and workplace variables | |||||

| Current position | 0.014 | ||||

| Administrative work | 2 (6.3) | 8 (25.0) | 12 (37.5) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Senior staff [supervisor] | 6 (15.8) | 9 (23.7) | 10 (26.3) | 13 (34.2) | |

| Staff/employee | 66 (29.2) | 48 (21.2) | 49 (21.7) | 63 (27.9) | |

| Training unit or work | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (42.9) | 7 (50.0) | |

| Research | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | 8 (57.1) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Organization type | <0.001 | ||||

| Retail or community pharmacy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Governmental hospital pharmacy | 38 (32.2) | 29 (24.6) | 19 (16.1) | 32 (27.1) | |

| Private hospital pharmacy | 16 (21.3) | 16 (21.3) | 17 (22.7) | 26 (34.7) | |

| Academic and research centers | 16 (31.4) | 12 (23.5) | 9 (17.6) | 14 (27.5) | |

| Pharmaceutical companies | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 9 (60.0) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Pharmaceutical industries | 4 (11.1) | 5 (13.9) | 17 (47.2) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Governmental facilities such as MOH and FDA | 1 (5.3) | 2 (10.5) | 8 (42.1) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Monthly income (SAR) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤9000 | 44 (29.3) | 40 (26.7) | 32 (21.3) | 34 (22.7) | |

| >9100 to 15,000 | 22 (22.4) | 12 (12.2) | 22 (22.4) | 42 (42.9) | |

| >15,000 to 21,000 | 6 (14.0) | 10 (23.3) | 15 (34.9) | 12 (27.9) | |

| >21,000 | 4 (10.3) | 8 (20.5) | 18 (46.2) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Professional Experience (years) | 0.155 | ||||

| ≤5 | 54 (28.6) | 43 (22.8) | 45 (23.8) | 47 (24.9) | |

| >5 to 15 | 17 (16.2) | 21 (20.0) | 30 (28.6) | 37 (35.2) | |

| >15 to 20 | 4 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) | 7 (35.0) | |

| >20 | 1 (6.3) | 2 (12.5) | 7 (43.8) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Currently work as a practicing pharmacist | 0.018 | ||||

| Yes | 70 (25.6) | 57 (20.9) | 64 (23.4) | 82 (30.0) | |

| No | 6 (10.5) | 13 (22.8) | 23 (40.4) | 15 (26.3) | |

| I Don’t Like My Job and I Have the Desire to Quit (n = 76) | I Like My Job but I Have the Desire to Quit OR I Don’t Like My Job but I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 70) | I Like My Job and I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 87) | Not Decided Whether to Quit or Not Regardless of Liking My Job (n = 97) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors related to workload | |||||

| Average of working hours per week? | 0.083 | ||||

| <30 | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) | |

| 30–39 | 3 (11.1) | 6 (22.2) | 13 (48.1) | 5 (18.5) | |

| 40–48 | 33 (21.9) | 28 (18.5) | 45 (29.8) | 45 (29.8) | |

| >48 | 36 (26.3) | 33 (24.1) | 24 (17.5) | 44 (32.1) | |

| Tasks to do in 4 h per day at work | 0.187 | ||||

| 1 task | 4 (28.6) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| 2 tasks | 9 (20.0) | 12 (26.7) | 10 (22.2) | 14 (31.1) | |

| 3 tasks | 11 (15.7) | 12 (17.1) | 28 (40.0) | 19 (27.1) | |

| ≥4 tasks | 52 (25.9) | 43 (21.4) | 44 (21.9) | 62 (30.8) | |

| Work in a shift system | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 60 (30.5) | 44 (22.3) | 42 (21.3) | 51 (25.9) | |

| No | 16 (12.0) | 26 (19.5) | 45 (33.8) | 46 (34.6) | |

| Work as teams or as individuals at work | 0.005 | ||||

| Teamwork | 14 (17.7) | 19 (24.1) | 28 (35.4) | 18 (22.8) | |

| Individual work | 18 (40.0) | 12 (26.7) | 4 (8.9) | 11 (24.4) | |

| Both | 44 (21.4) | 39 (18.9) | 55 (26.7) | 68 (33.0) | |

| Factors related to personnel compensation | |||||

| Earning enough money | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (11.1) | 20 (20.2) | 46 (46.5) | 22 (22.2) | |

| No | 65 (28.1) | 50 (21.6) | 41 (17.7) | 75 (32.5) | |

| Feeling rewarded for efforts | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (2.7) | 19 (17.3) | 59 (53.6) | 29 (26.4) | |

| No | 73 (33.3) | 51 (23.2) | 28 (12.7) | 68 (30.9) | |

| Feeling of personal accomplishment and satisfaction at work | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (2.2) | 33 (24.4) | 65 (48.1) | 34 (25.2) | |

| No | 53 (60.2) | 17 (19.3) | 4 (4.5) | 14 (15.9) | |

| Maybe | 20 (18.7) | 20 (18.7) | 18 (16.8) | 49 (45.8) | |

| Factors related to career development | |||||

| Institution provides opportunities for personal career growth and development | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 12 (9.4) | 22 (17.2) | 61 (47.7) | 33 (25.8) | |

| No | 64 (31.7) | 48 (23.8) | 26 (12.9) | 64 (31.7) | |

| Thinking about working for the same institution in the next 5 years | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (8.5) | 12 (16.9) | 42 (59.2) | 11 (15.5) | |

| No | 61 (43.3) | 37 (26.2) | 8 (5.7) | 35 (24.8) | |

| Maybe | 9 (7.6) | 21 (17.8) | 37 (31.4) | 51 (43.2) | |

| All Participants (n = 330) | I Don’t Like My Job and I Have the Desire to Quit (n = 76) | I Like My Job but I Have the Desire to Quit OR I Don’t Like My Job but I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 70) | I Like My Job and I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 87) | Not Deciding Whether to Quit or Not Regardless of Liking My Job (n = 97) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors increase job satisfaction | ||||||

| Promotion | 0.245 | |||||

| Yes | 248 (75.2) | 62 (25.0) | 47 (19.7) | 65 (26.2) | 74 (29.8) | |

| No | 82 (24.8) | 14 (17.1) | 23 (28.0) | 22 (26.8) | 23 (28.0) | |

| Good schedule | 0.002 | |||||

| Yes | 186 (56.4) | 56 (30.1) | 38 (20.4) | 49 (26.3) | 43 (23.1) | |

| No | 144 (43.6) | 20 (13.9) | 32 (22.2) | 38 (26.4) | 54 (37.5) | |

| Good wage | 0.579 | |||||

| Yes | 176 (53.3) | 45 (25.6) | 35 (19.9) | 43 (24.4) | 53 (30.1) | |

| No | 154 (46.7) | 31 (20.1) | 35 (22.7) | 44 (28.6) | 44 (28.6) | |

| Good teamwork | 0.264 | |||||

| Yes | 194 (58.8) | 45 (23.2) | 36 (18.6) | 58 (29.9) | 55 (28.4) | |

| No | 136 (41.2) | 31 (22.8) | 34 (25.0) | 29 (21.3) | 42 (30.9) | |

| Positive environment | 0.038 | |||||

| Yes | 249 (75.5) | 64 (25.7) | 47 (18.9) | 70 (28.1) | 68 (27.3) | |

| No | 81 (24.5) | 12 (14.8) | 23 (28.4) | 17 (21.0) | 29 (35.8) | |

| Opportunities | 0.310 | |||||

| Yes | 200 (60.6) | 53 (26.5) | 41 (20.5) | 49 (24.5) | 57 (28.5) | |

| No | 130 (39.4) | 23 (17.7) | 29 (22.3) | 38 (29.2) | 40 (30.8) | |

| Appreciation | 0.164 | |||||

| Yes | 182 (55.2) | 47 (25.8) | 31 (17.0) | 48 (26.4) | 56 (30.8) | |

| No | 147 (44.5) | 29 (19.7) | 39 (26.5) | 39 (26.5) | 40 (27.2) | |

| A supervisor’s leadership style | 0.048 | |||||

| Yes | 153 (46.4) | 42 (27.5) | 35 (22.9) | 42 (27.5) | 34 (22.2) | |

| No | 177 (53.6) | 34 (19.2) | 35 (19.8) | 45 (25.4) | 63 (35.6) | |

| Inspirational motivation | 0.062 | |||||

| Yes | 110 (33.3) | 35 (31.8) | 22 (20.0) | 25 (22.7) | 28 (25.5) | |

| No | 220 (66.7) | 41 (18.6) | 48 (21.8) | 62 (28.2) | 69 (31.4) | |

| Job security | 0.007 | |||||

| Yes | 159 (48.2) | 42 (26.4) | 29 (18.2) | 52 (32.7) | 36 (22.6) | |

| No | 171 (51.8) | 34 (19.9) | 41 (24.0) | 35 (20.5) | 61 (35.7) | |

| Involve employees in decisions | 0.059 | |||||

| Yes | 110 (33.3) | 35 (31.8) | 19 (17.3) | 27 (24.5) | 29 (26.4) | |

| No | 220 (66.7) | 41 (18.6) | 51 (23.2) | 60 (27.3) | 68 (30.9) | |

| All Participants (n = 330) | I Don’t Like My Job and I Have the Desire to Quit (n = 76) | I Like My Job but I Have the Desire to Quit OR I don’t Like My Job but I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 70) | I Like My Job and I Don’t Have the Desire to Quit (n = 87) | Not Decided Whether to Quit or Not Regardless of Liking My Job (n = 97) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods to increase motivation | ||||||

| Incentives and tuition | ||||||

| Yes | 127 (38.5) | 20 (15.7) | 25 (19.7) | 46 (36.2) | 36 (28.3) | |

| No | 203 (61.5) | 56 (27.6) | 45 (22.2) | 41 (20.2) | 61 (30.0) | 0.005 |

| Transport costs and health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 110 (33.3) | 17 (15.5) | 23 (20.9) | 38 (34.5) | 32 (29.1) | |

| No | 220 (66.7) | 59 (26.8) | 47 (21.4) | 49 (22.3) | 65 (29.5) | 0.04 |

| Allowance for a home | ||||||

| Yes | 86 (26.1) | 16 (18.6) | 19 (22.1) | 22 (25.6) | 29 (33.7) | |

| No | 192 (58.2) | 60 (24.6) | 51 (20.9) | 65 (26.6) | 68 (27.9) | 0.615 |

| Statement | Strongly Disagree, n (%) | Disagree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Agree, n (%) | Strongly Agree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational satisfaction | |||||

| I enjoy going to work every day | 45 (13.6) | 49 (14.8) | 134 (40.6) | 70 (21.2) | 32 (9.7) |

| My job gives me a sense of accomplishment | 42 (12.7) | 66 (20.0) | 81 (24.5) | 96 (29.1) | 45 (13.6) |

| I’m content with my work | 47 (14.2) | 51 (15.5) | 84 (25.5) | 99 (30.0) | 49 (14.8) |

| Others would consider my job a fortunate opportunity | 52 (15.8) | 48 (14.5) | 108 (32.7) | 77 (23.3) | 45 (13.6) |

| If I could start over, I would choose this job again | 74 (22.4) | 46 (13.9) | 73 (22.1) | 81 (24.5) | 56 (17.0) |

| Working environment | |||||

| I have confidence in the leadership of this organization | 63 (19.1) | 44 (13.3) | 106 (32.1) | 72 (21.8) | 45 (13.6) |

| To contribute to the success of my workplace, I am prepared to put in more effort than is often required | 42 (12.7) | 34 (10.3) | 77 (23.3) | 100 (30.3) | 77 (23.3) |

| My work environment motivates me to provide my best job performance | 75 (22.7) | 67 (20.3) | 92 (27.9) | 65 (19.7) | 31 (9.4) |

| Overall, I am satisfied with my work environment | 52 (15.8) | 54 (16.4) | 110 (33.3) | 80 (24.2) | 34 (10.3) |

| Empowerment | |||||

| I have enough discretion in my job to rely on my judgment | 36 (10.6) | 46 (13.9) | 114 (34.5) | 104 (31.5) | 31 (9.4) |

| I have the freedom to choose any working approach to do the job | 49 (14.8) | 73 (22.1) | 89 (27.0) | 93 (28.2) | 26 (7.9) |

| Financial aspect | |||||

| I’m content with my pay | 87 (26.4) | 64 (19.4) | 74 (22.4) | 73 (22.1) | 32 (9.7) |

| I am pleased with the additional benefits provided by my job | 75 (22.7) | 57 (17.3) | 88 (26.7) | 67 (20.3) | 43 (13.0) |

| Occupational dissatisfaction | |||||

| Staying with this organization doesn’t offer much in the way of benefits | 37 (11.2) | 37 (11.2) | 87 (26.4) | 86 (26.1) | 83 (25.2) |

| Deciding to work for this institution was a grave error | 75 (22.7) | 83 (25.2) | 95 (28.8) | 48 (14.5) | 29 (8.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharthi, A.; Aleiban, M.; Alwhaibi, A.; Alotaibi, M.; Almutairi, Y.; Alghadeer, S. Assessment of Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit Job Among Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060163

Alharthi A, Aleiban M, Alwhaibi A, Alotaibi M, Almutairi Y, Alghadeer S. Assessment of Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit Job Among Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060163

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharthi, Ashwaq, Maha Aleiban, Abdulrahman Alwhaibi, Moureq Alotaibi, Yousef Almutairi, and Sultan Alghadeer. 2025. "Assessment of Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit Job Among Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060163

APA StyleAlharthi, A., Aleiban, M., Alwhaibi, A., Alotaibi, M., Almutairi, Y., & Alghadeer, S. (2025). Assessment of Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit Job Among Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy, 13(6), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060163