Abstract

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly used to support critically ill adults with severe cardiac or respiratory failure, but ECMO circuits and the physiological disturbances of critical illness significantly alter drug pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD), complicating dosing and monitoring. This narrative review synthesizes current clinical evidence on ECMO-related PK/PD alterations and provides practical guidance for optimizing pharmacotherapy in adult intensive care. A structured literature search (January–May 2025) was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Sage Journals, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis Online, SpringerLink, and specialized databases, focusing on seven therapeutic classes commonly used in ECMO patients. Eligible studies included clinical trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and practice guidelines in adults, while pediatric and preclinical data were excluded. Evidence quality varied substantially across drug classes. Hydrophilic, low-protein-bound agents such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluconazole, and caspofungin generally showed minimal ECMO-specific PK alterations, with dose adjustment mainly driven by renal function. Conversely, lipophilic and highly protein-bound drugs including fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, voriconazole, and liposomal amphotericin B exhibited substantial circuit adsorption and variability, often requiring higher loading doses, prolonged infusions, and rigorous therapeutic drug monitoring. No ECMO-specific data were identified for certain neuromuscular blockers, antivirals, and electrolytes. Overall, individualized dosing guided by therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), organ function, and validated PK principles remains essential to optimize therapy in this complex population.

1. Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an advanced life support technique increasingly utilized to support patients with severe cardiac and respiratory failure. ECMO temporarily substitutes or supplements cardiopulmonary function by facilitating gas exchange, removing carbon dioxide, and enriching blood when conventional oxygen therapies, such as mechanical ventilation and pharmacological support, are insufficient [1]. Clinically, ECMO involves a closed extracorporeal circuit where blood is withdrawn via a cannula, pumped through an artificial membrane oxygenator, and subsequently returned to systemic circulation [2]. Common indications include severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), refractory cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, and other conditions characterized by profound respiratory or circulatory dysfunction [3,4]. Its use has significantly expanded in recent years, driven by advances in technology, refined protocols, and supportive clinical evidence.

Despite these benefits, ECMO poses significant pharmacokinetic challenges. The extracorporeal circuit comprising tubing, pumps, and membrane oxygenators can sequester medications such as antibiotics, antifungals, sedatives, analgesics, and other agents with high lipophilicity or extensive protein binding, leading to reduced plasma concentrations and potential therapeutic failure [5]. This phenomenon is primarily driven by physicochemical drug properties, particularly protein binding greater than 70% and log p-values above 2, which complicate dosing strategies [5]. In addition, ECMO patients frequently experience profound physiological alterations associated with critical illness, including expanded volume of distribution, hypoalbuminemia, impaired hepatic or renal clearance, and substantial fluid shifts, all of which further impair pharmacokinetic predictability [6,7]. As a result, conventional standardized dosing regimens may fail to achieve therapeutic targets, highlighting the need for individualized approaches, TDM and coordinated interdisciplinary management [5].

Pharmacokinetic alterations associated with ECMO are not uniform across age groups. Neonatal and infant studies have demonstrated distinct patterns, including maturational clearance, altered volume of distribution, and circuit-specific effects that differ substantially from older patients [8]. These age-dependent differences caution strongly against extrapolating pediatric or neonatal ECMO pharmacokinetics to adult populations. Accordingly, the present review focuses exclusively on adults, aiming to synthesize drug-specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data in critically ill adults on ECMO, where dedicated evidence remains comparatively scarce but is essential for optimizing therapy.

Several reviews have previously addressed pharmacokinetic alterations in ECMO. Some authors provided one of the earliest structured summaries, outlining circuit sequestration, increased volume of distribution, and altered clearance as potential mechanisms [9]. However, most of the data were derived from neonatal and pediatric ECMO, with very limited adult pharmacokinetic evidence, and practical guidance was minimal. More recently, the focus antimicrobials in adult ECMO, summarizing current dosing strategies but restricting scope to anti-infectives and providing largely narrative recommendations without critical bias appraisal or standardized evidence grading [10]. Some narrative reviews expanded the scope to include sedatives, analgesics, antimicrobials, and anticoagulants, offering broad coverage but still as a narrative synthesis, without systematic quality assessment or harmonization of infusion strategies and units [5].

In contrast, the present review provides a dedicated adult-only perspective, applies the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools across all included studies, and introduces a structured evidence grading framework (A–D). We also try to distinguish ECMO-specific circuit effects from critical-illness or renal/Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT)-driven variability, which is rarely made explicit in prior reviews. Furthermore, dosing recommendations are standardized with consistent units and infusion terminology (extended vs. continuous) and integrated with up-to-date data from recent Population Pharmacokinetics (PopPK) studies, therapeutic drug monitoring cohorts, and even randomized clinical trials on model-informed precision dosing. This approach allows the reader to weigh drug-specific recommendations across classes with greater transparency and clinical applicability than earlier reviews.

This review synthesizes the available evidence, summarizes dosing recommendations, and highlights existing gaps to improve pharmacotherapy in adult ECMO-supported patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed between January and May 2025 in PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Sage Journals, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis Online, and SpringerLink. Additionally, specialized clinical databases (Micromedex, DynaMed, UpToDate) were queried to capture non-indexed clinical recommendations. The strategy combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH and Boolean operators) with free-text keywords related to “extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” “critical illness,” and International Nonproprietary Names (INN) of commonly used intensive care medications. Database specific filters were applied. The database strategy search and filters are in Appendix A.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Adult patients (≥18 years) receiving ECMO support in intensive care units. Study designs: prospective or retrospective observational studies, interventional trials, systematic or narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical practice guidelines. Focus on pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), dosing strategies, or therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Publications in English or Spanish within the last 10 years.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Pediatric studies. Case reports or case series with <5 patients. Preclinical, in vitro, or ex vivo studies without direct clinical correlation. Editorials, expert opinions, or letters without original data.

2.3. Medication Selection

A multidisciplinary panel of intensivists and clinical pharmacists identified seven therapeutic classes frequently used in ECMO: (1) analgesics; (2) anesthetics and sedatives; (3) antimicrobials; (4) adrenergic agents; (5) anticoagulants; (6) neuromuscular blockers; and (7) electrolytes. Representative drugs within each class were chosen based on frequency of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) use, likelihood of ECMO-related PK/PD alterations, and preliminary evidence from scoping searches.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. For each included drug, extracted data included study design, population, ECMO modality (veno-venous or veno-arterial), reported PK/PD alterations, dosing regimens, TDM recommendations, and clinical precautions. Findings were synthesized narratively into drug-specific summaries and compiled into a structured pharmacotherapy guide.

2.5. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT, GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used to assist in text editing, rephrasing for clarity, and formatting. In addition, ChatGPT was employed to generate preliminary schematic elements and conceptual diagrams. These outputs were subsequently modified, refined, and integrated by the authors into the final figures included in this manuscript. It was not used for data extraction, data analysis, or interpretation of study results. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

2.6. Risk of Bias

The methodological quality and risk of bias of all included studies were critically appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools, applying the checklist appropriate to each study design (systematic reviews, cohort studies, case–control studies, analytical cross-sectional studies, and case series). Each tool evaluates domains related to study selection, validity of exposure and outcome measurements, identification and management of confounders, completeness of follow-up, and appropriateness of statistical analyses. Two independent reviewers independently performed the critical appraisal, assigning a judgment of Yes, No, Unclear, or Not applicable for each item. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.7. Evidence Grading and Target Harmonization

We assigned an A–D evidence grade to each drug based on study design and consistency (A: multicenter prospective/systematic review with consistent findings; B: prospective multicenter studies that analyses population pharmacokinetics or robust comparative cohorts; C: small single-center observational data; D: case series/reports or extrapolation). PK/PD denominators were harmonized across classes: β-lactams as %fT > MIC (with %fT > 4 × MIC for severe infections), aminoglycosides as Cmax/MIC, glycopeptides as AUC24/MIC, linezolid/azoles as trough (Cmin), and echinocandins as AUC/MIC.

3. Results

Our structured literature search identified a heterogeneous body of evidence spanning observational studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and limited interventional investigations in adult ECMO populations. The impact of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) on drug pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) was consistently shown to depend on both circuit-related factors (e.g., oxygenator type, tubing material, and duration of circuit use) and drug-specific physicochemical properties such as protein binding, lipophilicity, molecular weight, and volume of distribution. In addition, the profound physiological disturbances associated with critical illness, including altered clearance, fluid shifts, and changes in protein concentrations were found to contribute substantially to interpatient variability. Robust, multicenter pharmacokinetic studies remain scarce, and the quality of available data varied widely across therapeutic classes, ranging from well-characterized antimicrobials to drugs with little or no ECMO-specific evidence. The following sections summarize key findings by drug class, outlining patterns of PK/PD alterations and highlighting areas where individualized dosing, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), and clinical judgment are essential. A detailed synthesis of dosage recommendations, PK/PD considerations, monitoring strategies, alternatives, and clinical precautions is presented in a proposed guideline with Suggest Recommendations.

3.1. Analgesics

Among opioids, morphine exhibited minimal ECMO-related sequestration due to its hydrophilicity, although active metabolite accumulation remains a concern in renal dysfunction [11,12,13,14]. In contrast, fentanyl demonstrated significant circuit adsorption, requiring higher doses and individualized titration [15,16,17,18]. These findings highlight the need for close monitoring of efficacy and safety, with multimodal analgesia strategies often recommended.

3.2. Anesthetics and Sedatives

Ketamine showed limited sequestration, with variability mostly explained by critical illness rather than ECMO [19,20,21]. Propofol and midazolam, both highly lipophilic and protein-bound, were markedly affected by circuit adsorption, frequently necessitating higher doses and raising concerns about drug accumulation and adverse effects [15,22,23,24]. Diazepam is generally discouraged due to prolonged half-life and high adsorption risk [25,26,27]. Overall, sedative management requires careful titration and, when available, TDM [28].

3.3. Antimicrobials

Hydrophilic agents such as β-lactams (e.g., ceftazidime, meropenem) and aminoglycosides (e.g., amikacin) displayed minimal direct ECMO effects, with dose variability mainly driven by renal function and fluid balance [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Given the high PK variability observed in ECMO patients, embedding model-informed precision dosing (MIPD) with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for time-dependent antibiotics is particularly relevant. In critically ill adults, time-dependent antibiotics like β-lactams and ciprofloxacin the feasibility of Bayesian PK modeling with bedside TDM, although without improvement in ICU length of stay [37,38]. These results underscore that target attainment is challenging even in non-ECMO ICU cohorts, justifying the adoption of proactive MIPD/TDM workflows (extended or continuous infusions, systematic auditing of PK/PD targets) in ECMO, where variability is at least as great [37]. In contrast, lipophilic antifungals like voriconazole and liposomal amphotericin B showed pronounced sequestration and interpatient variability, often requiring dose escalation and rigorous TDM [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Agents such as linezolid and vancomycin exhibited mixed results, with individualized dosing and monitoring strongly advised [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. For several drugs, including ganciclovir, acyclovir, and certain antivirals, no ECMO-specific clinical data were available.

3.4. Adrenergic Agents

Norepinephrine pharmacokinetics appeared largely unaffected by ECMO, with dose requirements reflecting illness severity rather than circuit effects [61,62,63]. Conversely, epinephrine use in VA-ECMO was associated with increased mortality and adverse outcomes, warranting restriction to refractory scenarios [64,65]. Dobutamine showed limited data, with recommendations favoring cautious use at low doses or alternatives such as milrinone or levosimendan [66].

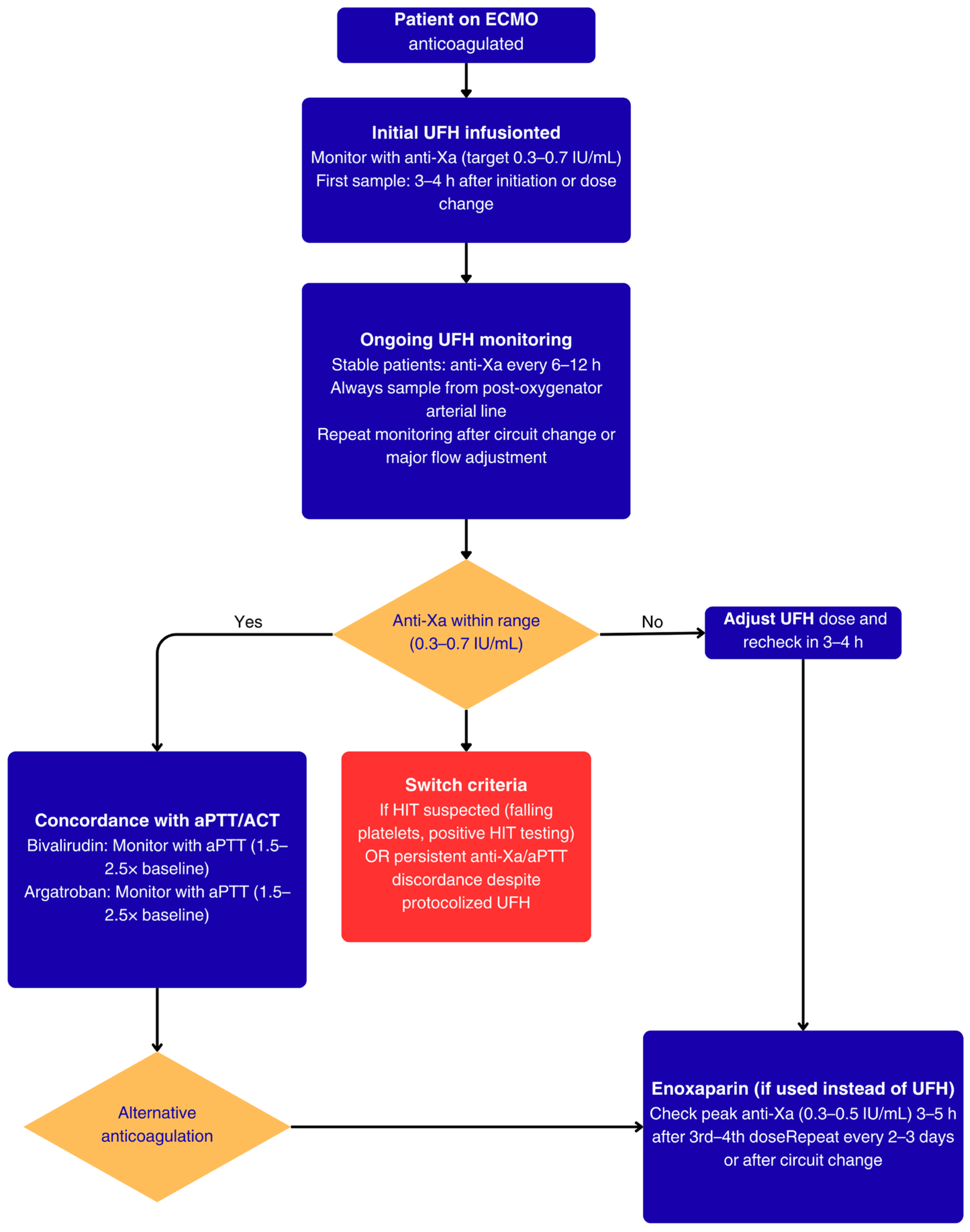

3.5. Anticoagulants

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) remains the standard anticoagulant, with minimal circuit sequestration but high interpatient variability, necessitating multimodal monitoring of Anti-factor Xa (FXa), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT), and Activated Clotting Time (ACT) (anti-FXa, aPTT, ACT) [67,68,69,70,71,72]. Enoxaparin, used either subcutaneously or intravenously, emerged as a feasible alternative with stable PK profiles and comparable safety, although evidence remains limited [73,74]. Alternatives such as bivalirudin and argatroban may be considered in cases of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or organ dysfunction [75,76].

3.6. Neuromuscular Blockers

Evidence was scarce for this class. Rocuronium was noted for potential accumulation due to its lipophilicity and hepatic metabolism, but clinical data were insufficient to define ECMO-specific dosing adjustments. Cisatracurium is generally preferred because of its organ-independent metabolism [22,77,78].

3.7. Electrolytes

For agents such as potassium chloride, magnesium sulfate, calcium gluconate, and potassium phosphate, no ECMO-specific pharmacokinetic data were identified. Current practice relies on standard ICU dosing with careful titration according to serum levels and organ function. These represent critical evidence gaps that warrant further research.

3.8. Study Selection

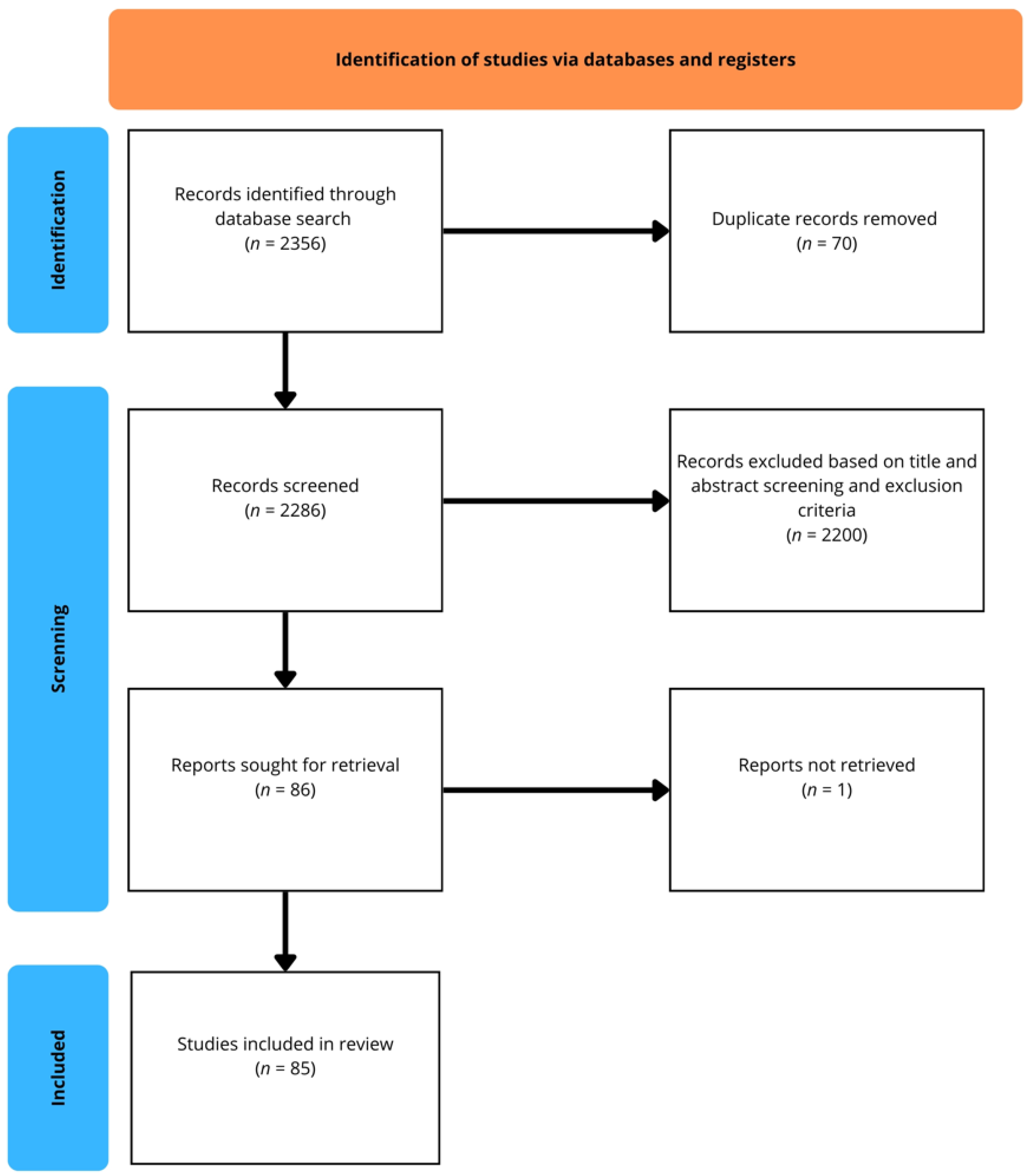

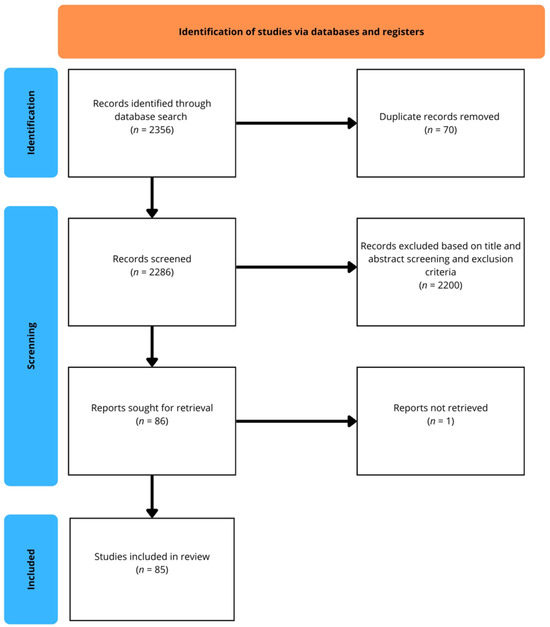

A structured literature search was conducted across multiple databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Sage Journals, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis Online, and SpringerLink). The initial search yielded a total of 2356 records. After the removal of 70 duplicates, 2286 records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 2200 were excluded for not meeting the predefined eligibility criteria. A total of 86 reports were sought for full-text retrieval; however, one could not be accessed. Finally, 85 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the qualitative synthesis. The selection process is illustrated in the flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

3.9. Methodological Quality

3.9.1. Evaluation Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool

In Section 3.9.1, two reviewers (J.C.F. and E.Z.M.) applied the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews, Textual Evidence: Narrative, Cohort Studies, Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies, Case Series, Case–Control Studies. Details of these assessments are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 1.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews.

Table 2.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Narrative Reviews.

Table 3.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Cohort Studies.

Table 4.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies.

Table 5.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Case Series.

Table 6.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Prevalence Studies Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Case–Control Studies.

3.9.2. Summary of Evidence Quality

Table 7 shows that β-lactams and vancomycin reach B-level evidence with broadly consistent ECMO findings (circuit effects modest; renal function/CRRT drives variability), supporting extended/continuous infusions and TDM. Antifungals and sedatives are mostly C–D, with under-exposure (e.g., voriconazole) or early sequestration (e.g., midazolam/propofol), reinforcing trough or AUC-guided approaches and individualized dosing. Formal systematic reviews do exist, but their own conclusions are that adult ECMO data are sparse/heterogeneous and often observational, with few drug-specific, consistent dosing conclusions so they do not lift any single drug to Grade A. In contrast, several agents do reach Grade B thanks to prospective multicenter studies that analyses population pharmacokinetics or comparative cohorts (e.g., vancomycin, piperacillin–tazobactam, meropenem, amikacin, UFH monitoring strategies), but not A.

Table 7.

Evidence grading and standardized PK/PD targets for commonly used drugs during ECMO.

3.10. Drugs with No ECMO Data

Using our predefined search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria, we did not identify any adult ECMO-specific pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic data for several clinically relevant agents. These included the non-opioid analgesics metamizole (dipyrone) and paracetamol (acetaminophen); the local anesthetic lidocaine; the antimicrobial agents metronidazole, ganciclovir, and acyclovir; the neuromuscular blocking agents atracurium and pancuronium; and parenteral electrolyte supplements (e.g., potassium chloride, magnesium sulfate, calcium gluconate, phosphate).

3.11. Guideline with Suggest Recommendations

To facilitate clinical application, the evidence synthesized in this review was organized into a structured pharmacotherapy guide (Table 8). The table provides a concise summary of key pharmacotherapeutic aspects for medications commonly used in critically ill adult ECMO patients, grouped by therapeutic class. For each drug, essential information is presented, including dosage recommendations, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic considerations, therapeutic drug monitoring targets, available alternatives, and clinical indications or precautions. This format allows rapid comparison across drug classes and highlights areas where robust evidence exists versus those where data remain scarce. Given the high PK variability in ECMO, embedding MIPD/TDM for time-dependent drugs aligns with randomized data showing improved feasibility of target-attainment strategies in the general ICU, and is likely even more relevant in ECMO patients [37]. Unless explicitly noted as ECMO practice–specific are derived from general ICU literature and applied to ECMO, for which adult studies confirm high variability but do not define new thresholds.

Table 8.

Management and Considerations of Commonly used medications in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in patients undergoing ECMO therapy.

4. Discussion

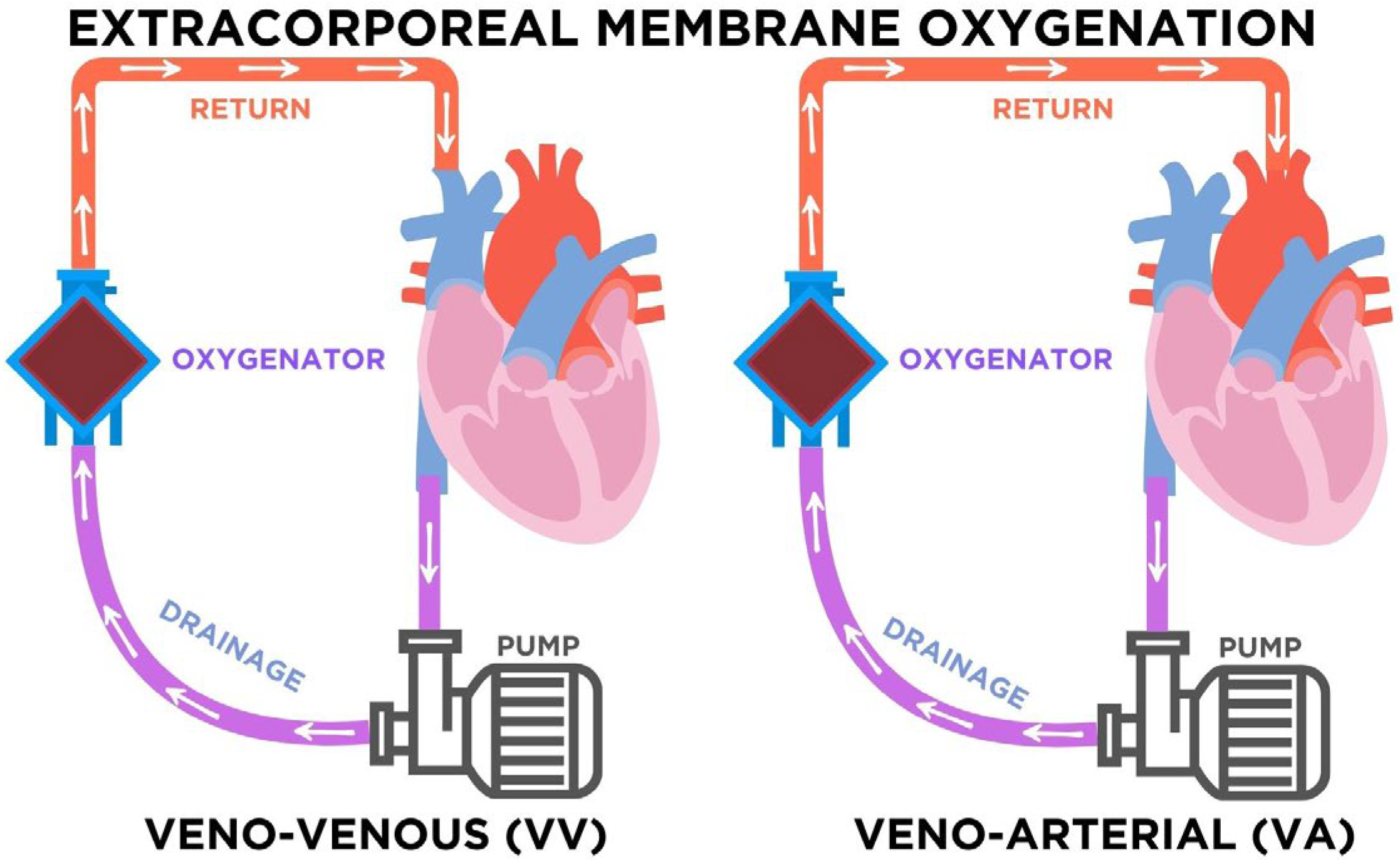

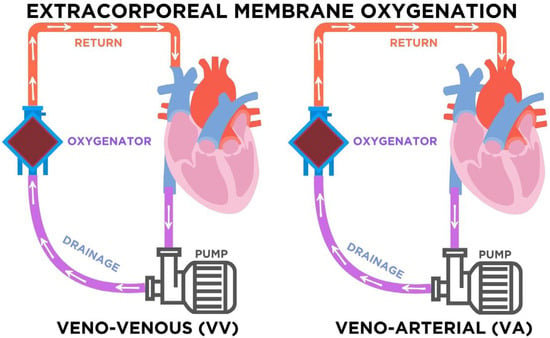

The use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has transitioned from a last-resort salvage therapy to a widely applied intervention in intensive care units [1,2,3,4]. As illustrated in Figure 2, ECMO consists of a centrifugal pump and a membrane oxygenator that drains venous blood, removes carbon dioxide, and returns oxygenated blood to the patient’s circulation. In veno-venous (VV) ECMO, blood is drained and reinfused into the venous system, providing exclusive respiratory support while preserving native cardiac output. In contrast, veno-arterial (VA) ECMO reinfuses blood into arterial circulation, supporting both respiratory and circulatory function. The choice of modality depends on the clinical condition: VV-ECMO is preferred in severe isolated respiratory failure such as ARDS, whereas VA-ECMO is indicated in refractory cardiogenic shock or profound cardiac dysfunction [1,2,3,4]. This distinction is relevant not only physiologically but also pharmacologically, since modality-specific factors influence drug distribution, anticoagulation needs, and vasopressor requirements [61,64,84,87,96].

Figure 2.

Configurations of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). In veno-venous (VV) ECMO, venous blood is drained, pumped through the oxygenator, and returned to the venous system, providing respiratory support. In veno-arterial (VA) ECMO, venous blood is drained and returned to the arterial system, supporting both respiratory and circulatory function. Arrows indicate the direction of blood flow through the circuit. The purple arrows represent deoxygenated blood draining from the venous system toward the pump and oxygenator, while the red arrows represent oxygenated blood returning to the patient. The blue components correspond to the oxygenator, where gas exchange occurs.

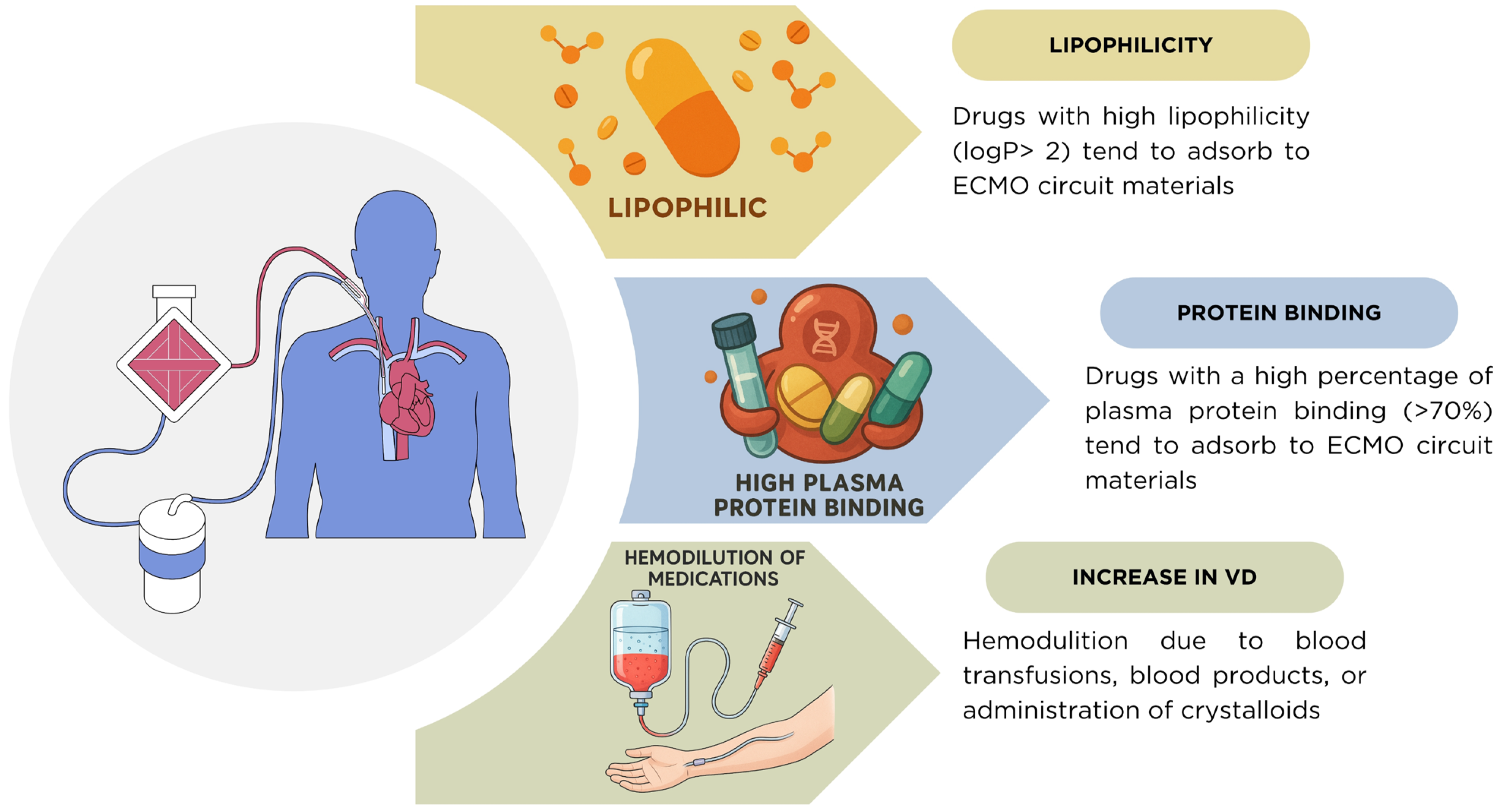

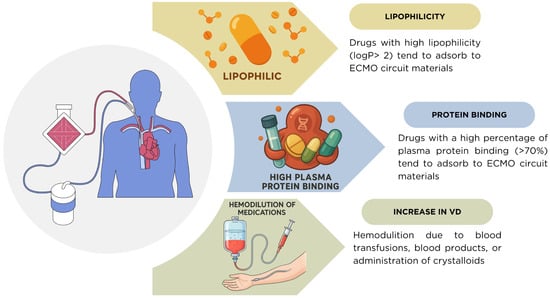

Another fundamental determinant of pharmacokinetic (PK) variability during ECMO is the interaction between drug properties and fluid dynamics. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 9, drugs with high lipophilicity (logP > 2) and plasma protein binding greater than 70% are highly susceptible to adsorption within ECMO circuit components, leading to subtherapeutic plasma concentrations [5,22]. In addition, critically ill patients frequently undergo hemodilution from blood transfusions, administration of blood products, and crystalloid infusion used to maintain circuit flow. These interventions expand the apparent volume of distribution (Vd) and contribute to underexposure, compounding the impact of circuit adsorption [6,7]. The combination of these factors underscores the need for individualized dosing and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in ECMO patients.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of pharmacokinetic alterations during ECMO. Drugs with high lipophilicity (logP > 2) and high plasma protein binding (>70%) tend to adsorb onto ECMO circuit components, reducing plasma concentrations. In addition, the volume of distribution (Vd) is frequently increased due to hemodilution from blood transfusions, blood products, or crystalloid administration, further complicating drug exposure in critically ill ECMO patients.

Table 9.

Relationship between physicochemical properties and exposure changes in adult ECMO patients.

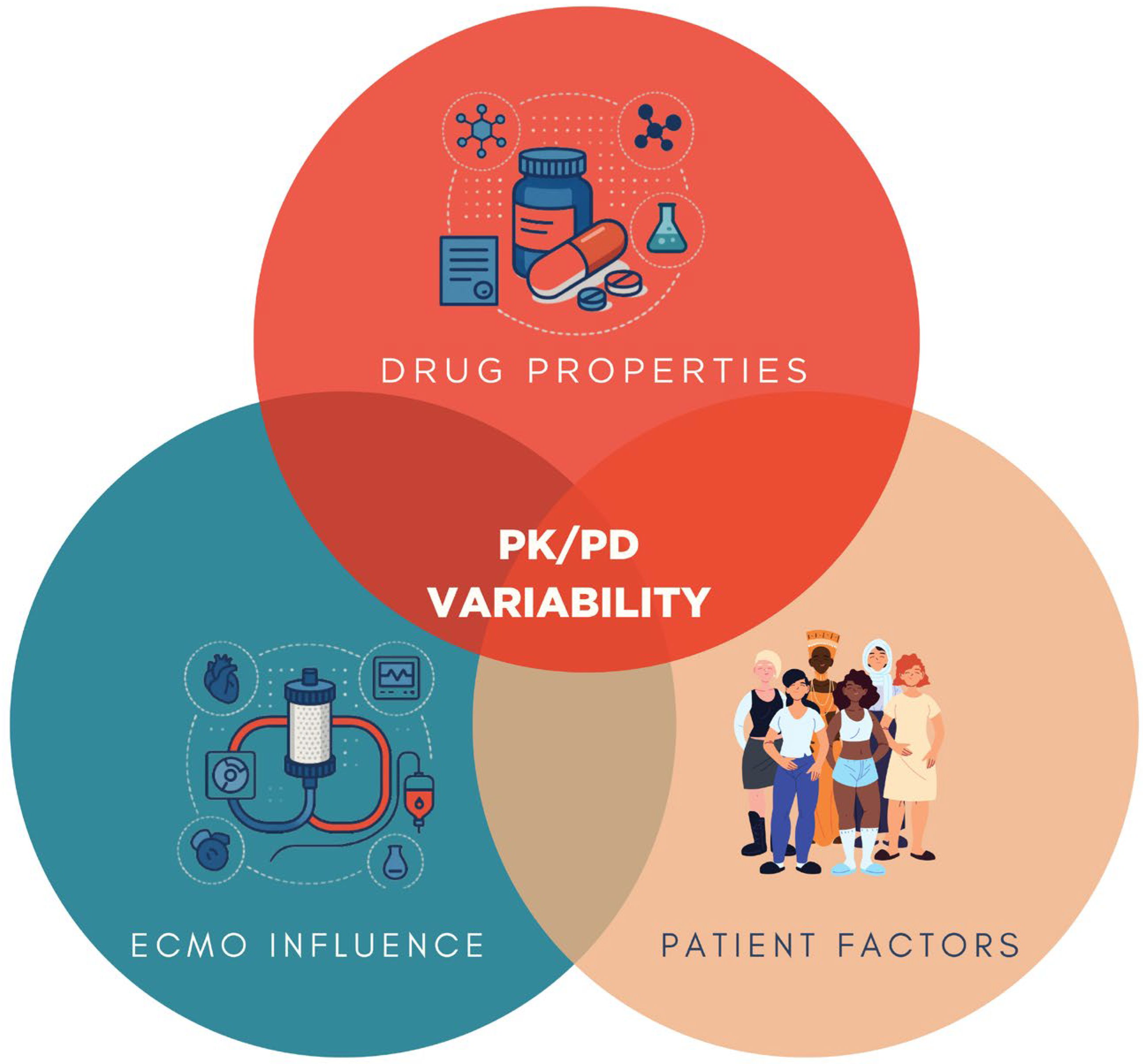

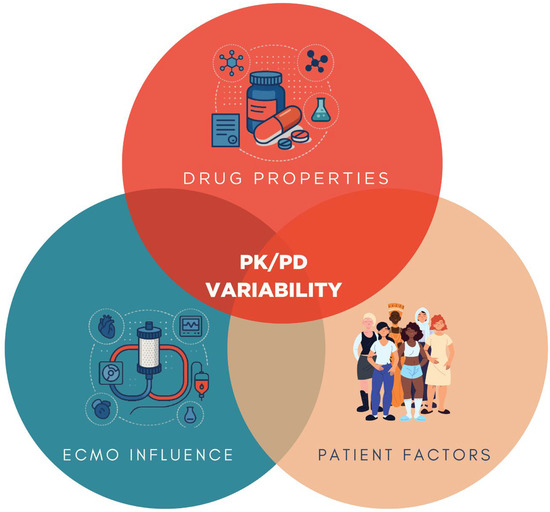

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) variability in ECMO is ultimately the result of a triad of influences: drug-related, patient-specific, and ECMO circuit-related factors. As illustrated in Figure 4, the properties of each medication including lipophilicity, protein binding, molecular weight, and volume of distribution serve as primary determinants of sequestration and clearance [5,22]. Patient-related factors such as opioid tolerance, body mass index, fluid balance, hepatic and renal function, and systemic inflammation further modulate drug disposition and effect [6,7]. In parallel, the ECMO circuit itself adsorbs lipophilic and protein-bound drugs onto oxygenator membranes and tubing surfaces [5,22]. This interplay explains much of the interindividual variability observed in drug exposure and reinforces the need for precision pharmacotherapy based on mechanistic understanding, clinical context, and TDM.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework of PK/PD variability in ECMO. Drug properties (lipophilicity, protein binding, molecular weight, volume of distribution), patient factors (opioid tolerance, body mass index, fluid balance, hepatic and renal function), and ECMO circuit influence (drug sequestration by circuit components) interact to determine pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic alterations in critically ill patients supported with ECMO.

It is also important to situate adult findings within the broader ECMO literature. Pharmacokinetic alterations during ECMO are not homogeneous across age groups. Neonatal and infant studies have demonstrated distinct maturational clearance and circuit/device effects, underscoring the strong influence of developmental physiology on drug disposition [8]. These age-dependent differences caution against extrapolating pediatric or neonatal data to adults. By explicitly separating adult evidence, the present review highlights that dosing strategies must be tailored to age group and clinical context, and that robust adult-specific pharmacokinetic data remains essential for optimizing therapy.

Clinical data consistently show that opioids and sedatives behave differently during ECMO. Morphine, due to its hydrophilic nature and moderate protein binding, demonstrates limited sequestration; however, accumulation of active metabolites in renal dysfunction requires close monitoring [11,12,13,14]. In contrast, fentanyl is highly lipophilic and protein-bound, making it prone to unpredictable adsorption and increased dose requirements [15,16,17,18]. Benzodiazepines, particularly midazolam, accumulate significantly, leading to delayed awakening and increased risk of delirium [22,24]. Propofol, while susceptible to circuit adsorption, generally achieves sedation targets with careful titration, though clinicians must remain vigilant for metabolic complications such as hypertriglyceridemia and propofol infusion syndrome [15,23]. Ketamine appears less affected by ECMO circuits, with observed variability largely attributable to the underlying critical illness rather than the extracorporeal system itself [19,20,21].

Infection management in ECMO patients represents one of the most consequential pharmacotherapeutic challenges. Hydrophilic antibiotics such as β-lactams (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, meropenem, piperacillin–tazobactam) and aminoglycosides (amikacin) generally exhibit minimal circuit sequestration, but altered distribution volumes and clearance frequently necessitate prolonged or continuous infusion strategies to maintain time-dependent exposure [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,48,79,90,91,92,93,98,108,109,113,114]. Vancomycin is minimally influenced by the circuit itself; however, high interpatient variability driven by renal function and systemic inflammation underscores the importance of AUC-guided TDM [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,99]. Linezolid demonstrates inconsistent plasma concentrations, with frequent subtherapeutic exposures, highlighting the need for individualized monitoring [49,50]. Aminoglycosides, although not heavily sequestered, often require higher loading doses to achieve bactericidal peaks [29,30,31,32,33].

Antifungal therapy illustrates the heterogeneity of ECMO pharmacokinetics. Fluconazole remains reassuringly stable [39,83]. By contrast, voriconazole and posaconazole frequently show subtherapeutic concentrations despite standard dosing, mandating dose escalation and rigorous TDM [44,45,46,47]. Caspofungin appears relatively unaffected, though higher doses may be required in patients with elevated body weight or severe illness [81,82,94,95]. Liposomal amphotericin B is particularly problematic, with pronounced circuit adsorption leading to highly variable plasma concentrations and unpredictable efficacy [39,40,43].

Evidence for antiviral therapy in ECMO is almost entirely lacking. Drugs such as ganciclovir and acyclovir have no ECMO-specific PK/PD data, and dosing recommendations are currently extrapolated from non-ECMO populations. This represents a critical evidence gap that urgently requires targeted investigation.

Vasopressor and inotrope use in ECMO highlights the interplay between illness severity and pharmacokinetics. Norepinephrine remains the most widely used first-line vasopressor, with minimal ECMO-specific alterations; observed dose variability largely reflects disease severity [61,62,63,84]. Epinephrine use in VA-ECMO, however, has been associated with increased mortality and adverse outcomes, and should therefore be reserved for refractory situations [64,65]. Dobutamine data are limited, but high-dose use carries risks of arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy; alternatives such as milrinone or levosimendan are generally favored [66].

Anticoagulation is central to ECMO management but fraught with variability. Unfractionated heparin remains the global standard; however, interpatient differences in inflammation, antithrombin activity, and organ function make dose adjustment highly individualized. Anti-FXa monitoring provides more consistent results than ACT or aPTT, though multimodal strategies are increasingly recommended [67,68,69,70]. Enoxaparin is an emerging alternative with a more predictable PK profile, though clinical evidence is limited [73,74]. Direct thrombin inhibitors such as bivalirudin and argatroban are attractive options due to more predictable PK, but their broader adoption remains limited by cost and lack of multicenter outcome data [75,76,89,96].

The data about neuromuscular blockers is scarce, rocuronium, being lipophilic and hepatically metabolized, may accumulate during ECMO, raising concerns about prolonged neuromuscular blockade [22,77,78]. By contrast, cisatracurium metabolized independently of hepatic or renal function remains the agent of choice due to its more predictable pharmacokinetics [22,77,78].

In commonly used electrolytes such as calcium gluconate, magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride, and potassium phosphate, no ECMO-specific PK data exist. Current dosing is extrapolated from conventional ICU practice, with therapy guided by serial serum monitoring and patient-specific requirements. These gaps represent an underexplored yet clinically important area of ECMO pharmacotherapy.

In summary, physicochemical drug properties provide important but incomplete predictors of ECMO-related PK/PD alterations, as patient physiology and circuit factors exert substantial influence. TDM is indispensable for high-risk medications such as vancomycin, aminoglycosides, linezolid, and azole antifungals. Extended or continuous infusion strategies should be prioritized for β-lactams. Clinicians should favor drugs with more predictable PK behavior when alternatives exist (e.g., morphine over fentanyl, cisatracurium over rocuronium). However, current evidence remains limited by small, retrospective, and single-center studies, underscoring the urgent need for multicenter trials and standardized monitoring protocols.

5. Conclusions

Optimizing pharmacotherapy in ECMO-supported critically ill adults requires integrating drug physicochemical properties, patient-specific physiology, and circuit-related influences into individualized treatment strategies. Lipophilic and highly protein-bound medications are most vulnerable to sequestration, while hydrophilic agents are affected predominantly by organ dysfunction and fluid shifts. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) remains essential for high-risk drugs, including vancomycin, aminoglycosides, linezolid, and azole antifungals, whereas prolonged or continuous infusions should be prioritized for β-lactams. When possible, clinicians should favor medications with predictable PK/PD behavior, such as morphine or cisatracurium, over agents with high variability. Current evidence is constrained by small, retrospective, or ex vivo studies, with limited modality-specific (VV vs. VA) comparisons. Future priorities include multicenter clinical trials, standardized TDM protocols, and physiologically based PK modeling to refine dosing recommendations across drug classes. Bridging these knowledge gaps will be crucial to ensure safer and more effective pharmacotherapy in patients requiring ECMO support.

6. Future Directions

Several clinically relevant drugs remain without adult ECMO-specific PK/PD data, including paracetamol, metamizole, lidocaine, metronidazole, acyclovir, ganciclovir, atracurium, pancuronium, and commonly administered electrolytes. Future work should prioritize prospective population PK studies in these domains. For neuromuscular blocking agents, research is needed to clarify circuit adsorption and define depth-of-block monitoring strategies. For antivirals such as acyclovir and ganciclovir, studies should integrate PK with viral load dynamics, renal replacement therapy, and circuit covariates. For widely used non-opioid analgesics and antibiotics, prospective PK/PD investigations are required to determine whether ECMO alters distribution or clearance. Finally, systematic kinetic studies of intravenous electrolytes (potassium, magnesium, calcium, phosphate) could inform pragmatic replacement algorithms tailored to ECMO patients. Addressing these knowledge gaps will be critical to reduce reliance on extrapolation from non-ECMO ICU cohorts and to build a more comprehensive evidence base for drug dosing in adult ECMO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.C.-F. and F.C.-F.; methodology, J.M.C.-F. and E.Z.-M.; validation, A.R.-R., J.M.C.-F. and E.Z.-M.; formal analysis, A.R.-R. and J.M.C.-F.; investigation, A.R.-R. and J.M.C.-F.; resources, E.Z.-M.; data curation, A.R.-R. and J.M.C.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.-R., F.C.-F. and J.M.C.-F.; writing—review and editing, F.C.-F., J.M.C.-F., A.R.-R., and E.Z.-M.; visualization, A.R.-R.; supervision, F.C.-F., J.M.C.-F. and E.Z.-M.; project administration, F.C.-F., J.M.C.-F. and E.Z.-M.; funding acquisition, E.Z.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Clínica Bíblica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by the Department of Pharmacy at Clínica Bíblica, Costa Rica. The authors also acknowledge Clínica Bíblica for covering the article processing charge (APC) of this publication. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) to assist with text editing, rephrasing for clarity, and formatting in accordance with journal guidelines. In addition, ChatGPT was employed to generate preliminary schematic elements and conceptual diagrams. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| ACT | Activated Clotting Time |

| ARC | Augmented Renal Clearance |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BPS | Behavioral Pain Scale |

| CI | Cardiac Index/Continuous Infusion (specify in context) |

| CL | Clearance |

| CPOT | Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool |

| CRRT | Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

| EI | Extended Infusion |

| FXa | Anti-factor Xa |

| HIT | Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| INN | International Nonproprietary Name |

| IV | Intravenous |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes |

| LD | Loading Dose |

| MAP | Mean Arterial Pressure |

| MDR | Multi-Drug-Resistant |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PD | Pharmacodynamics |

| PopPK | Population Pharmacokinetics |

| PRIS | Propofol Infusion Syndrome |

| RASS | Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale |

| SvO2 | Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation |

| TDM | Therapeutic Drug Monitoring |

| UFH | Unfractionated Heparin |

| VA-ECMO | Veno-arterial ECMO |

| Vd | Volume of Distribution |

| VV-ECMO | Veno-venous ECMO |

| t½ | Elimination half-life |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Selected databases, keywords, search strategies, and filters used in the initial article retrieval process.

Table A1.

Selected databases, keywords, search strategies, and filters used in the initial article retrieval process.

| Date Base | Search Strategy | Filters Applied in the Datebase | Date of Last Searched |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | (“Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation” [Mesh] OR ECMO OR “Extracorporeal Life Support”) AND (“Intensive Care Units” [Mesh] OR “Critical Care” [Mesh] OR ICU OR “Intensive Care”) AND (“INN” [Mesh]) AND (“Pharmacokinetics” [Mesh] OR pharmacokinetics OR “Dose-Response Relationship, Drug” [Mesh] OR “Dose Titration” OR therapeutic monitoring) AND (“Adult” [Mesh] OR adult OR “young adult” [Mesh] OR “middle aged” [Mesh] OR “Aged” [Mesh]) “INN dose adjustment on ECMO” “INN pharmacokinetics on ECMO” | Clinical Study, Clinical Trial, Guideline, Meta-Analysis, Observational Study, Randomized Controlled Trial, Review, Systematic Review, in Adult: 19+ years, published in the Last 10 Years. | 11 May 2025 |

| EMBASE | (‘extracorporeal membrane oxygenation’/exp OR ECMO OR ‘extracorporeal life support’) AND (‘intensive care unit’/exp OR ICU OR ‘critical care’ OR ‘intensive care’) AND (‘INN’) AND (‘pharmacokinetics’/exp OR ‘pharmacodynamics’/exp OR ‘dose titration’/exp OR ‘therapeutic drug monitoring’/exp) “INN dose adjustment on ECMO” “INN pharmacokinetics on ECMO” | Articles, Review Articles and clinical trials published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| Scopus | (“extracorporeal membrane oxygenation” OR ECMO OR “extracorporeal life support”) (“intensive care” OR ICU OR “critical care”) (“INN”) (“pharmacokinetics” OR “pharmacodynamics” OR “dose titration” OR “therapeutic monitoring”) (“adult” OR “patients over 18 years”) “INN dose adjustment on ECMO” “INN pharmacokinetics on ECMO” | Articles and Review Articles published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| Cochrane Library | “INN” AND “ECMO” | Clinical Trials, Observational Studies, Systematic Reviews, and Meta-analyses published in the Last 10 Years. | 11 May 2025 |

| Sage Journals | “INN AND Dose Adjustment AND Pharmacokinetics AND Pharmacodynamics AND Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation AND Adults” | Research Articles and Review Articles published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| ScienceDirect | “INN AND Dose Adjustment AND Pharmacokinetics AND Pharmacodynamics AND Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation AND Adults” | Research Articles, Review Articles and Practice Guidelines published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| Taylor & Francis Online | “INN AND Dose Adjustment AND Pharmacokinetics AND Pharmacodynamics AND Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation AND Adults” | Articles published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| SpringerLink | “INN AND Dose Adjustment AND Pharmacokinetics AND Pharmacodynamics AND Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation AND Adults” | Articles, Research Articles, Review Articles and Practice Guidelines published in the Last 10 Years | 11 May 2025 |

| Specialized clinical databases (Micromedex, DynaMed, UpToDate) | INN | N.A. | 11 May 2025 |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Anticoagulation monitoring pathway in ECMO patients.

Figure A1.

Anticoagulation monitoring pathway in ECMO patients.

References

- Bartlett, R.H. The Story of ECMO. Anesthesiology 2024, 140, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, K.; Cabrales, P. Extracorporeal circulation impairs microcirculation perfusion and organ function. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, D.; Slutsky, A.S.; Combes, A. Extracorporeal Life Support for Adults with Respiratory Failure and Related Indications: A Review. JAMA 2019, 322, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.J.; Shah, R.V.; Murthy, V.; McCullough, S.A.; Reza, N.; Thomas, S.S.; Song, T.H.; Newton-Cheh, C.H.; Camuso, J.M.; MacGillivray, T.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes in Adults with Cardiogenic Shock Supported by Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 116, 1624–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.S.; Kooda, K.; Igneri, L.A. A Narrative Review of the Impact of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Critical Care Therapies. Ann. Pharmacother. 2023, 57, 706–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Creteur, J. The Critically Ill Patient. Critical Care Nephrology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–4.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayambankadzanja, R.K.; Schell, C.O.; Wärnberg, M.G.; Tamras, T.; Mollazadegan, H.; Holmberg, M.; Alvesson, H.M.; Baker, T. Towards definitions of critical illness and critical care using concept analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, N.; Sürmelioğlu, N.; Allegaert, K. Population pharmacokinetics in critically ill neonates and infants undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A literature review. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2022, 6, e001512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekar, K.; Fraser, J.F.; Smith, M.T.; Roberts, J.A. Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Crit. Care 2012, 27, 741.e9–741.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Mahmood, M.; Estes, L.L.; Wilson, J.W.; Martin, N.J.; Marcus, J.E.; Mittal, A.; O’Connell, C.R.; Shah, A. A narrative review on antimicrobial dosing in adult critically ill patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochroch, J.; Usman, A.; Kiefer, J.; Pulton, D.; Shah, R.; Grosh, T.; Patel, S.; Vernick, W.; Gutsche, J.T.; Raiten, J. Reducing Opioid Use in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery—Preoperative, Intraoperative, and Critical Care Strategies. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Ai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, L.; Ma, X. Sedation and analgesia requirements during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Perfusion 2023, 38, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.G.; Peahota, M.; Thoma, B.N.; Kraft, W.K. Medication Complications in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Crit. Care Clin. 2017, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.-L.; Bacchetta, M.D.; Spellman, J. Anesthetic management of the patient with extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 31, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierba, A.L.; Muir, J.; Dilawri, A.; Buckley, M.S. Optimizing pharmacotherapy regimens in adult patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A narrative review for clinical pharmacists. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2023, 6, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigoghossian, C.D.; Dzierba, A.L.; Etheridge, J.; Roberts, R.; Muir, J.; Brodie, D.; Schumaker, G.; Bacchetta, M.; Ruthazer, R.; Devlin, J.W. Effect of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Use on Sedative Requirements in Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 2016, 36, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Altshuler, D.; Lewis, T.C.; Merchan, C.; Smith, D.E.; Toy, B.; Zakhary, B.; Papadopoulos, J. Sedation Requirements in Patients on Venovenous or Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Ann. Pharmacother. 2020, 54, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolf, K.M.; Rivosecchi, R.M.; Goméz, H.; Sciortino, C.M.; Murray, H.N.; Padmanabhan, R.R.; Sanchez, P.G.; Harano, T.; Sappington, P.L. Comparison of Hydromorphone versus Fentanyl-based Sedation in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, T.; Mercer, K.; Johnson, P.N.; Miller, J.; Yousaf, F.S.; Fuller, J.A. Ketamine Use in Adult and Pediatric Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO): A Systematic Review. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 37, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketamine—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/ketamine#GUID-03D42B8D-4002-40FC-98D6-D1D375256C84 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Ketamine: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ketamine-drug-information (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Dreucean, D.; Harris, J.E.; Voore, P.; Donahue, K.R. Approach to Sedation and Analgesia in COVID-19 Patients on Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Ann. Pharmacother. 2022, 56, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, W.; Nagler, B.; Hermann, A.; Robak, O.; Schellongowski, P.; Buchtele, N.; Bojic, A.; Schmid, M.; Zauner, C.; Heinz, G.; et al. Propofol-based sedation does not negatively influence oxygenator running time compared to midazolam in patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2019, 42, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.A.; Sieg, A.C. Evaluation of Altered Drug Pharmacokinetics in Critically Ill Adults Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Pharmacotherapy 2017, 37, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofte, I.; Terrin, M.; Barr, E.; Kim, J.; Rinaldi, J.; Ladikos, N.; Menaker, J.; Tabatabai, A.; Kon, Z.; Griffith, B.; et al. Adaptive periodic paralysis allows weaning deep sedation overcoming the drowning syndrome in ECMO patients bridged for lung transplantation: A case series. J. Crit. Care 2017, 42, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diazepam—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/diazepam#GUID-92E83FD7-E214-4F12-899E-56BFBCF23686 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Diazepam: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diazepam-drug-information (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Schaller, A.M.; Feih, J.T.; Juul, J.J.; Rein, L.E.; Duewell, B.E.; Makker, H. A Retrospective Cohort Analysis of Analgosedation Requirements in COVID-19 Compared to Non-COVID-19 Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Patients. J. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 40, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touchard, C.; Aubry, A.; Eloy, P.; Bréchot, N.; Lebreton, G.; Franchineau, G.; Besset, S.; Hékimian, G.; Nieszkowska, A.; Leprince, P.; et al. Predictors of insufficient peak amikacin concentration in critically ill patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouglé, A.; Dujardin, O.; Lepère, V.; Hamou, N.A.; Vidal, C.; Lebreton, G.; Salem, J.-E.; El-Helali, N.; Petijean, G.; Amour, J. PHARMECMO: Therapeutic drug monitoring and adequacy of current dosing regimens of antibiotics in patients on Extracorporeal Life Support. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2019, 38, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramos, J.; Gimeno, R.; Pérez, F.; Ramirez, P.; Villarreal, E.; Gordon, M.; Vicent, C.; Marqués, M.R.; Castellanos-Ortega, Á. Pharmacokinetics of Amikacin in Critical Care Patients on Extracorporeal Device. ASAIO J. 2018, 64, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressiat, C.; Kudela, A.; De Roux, Q.; Khoudour, N.; Alessandri, C.; Haouache, H.; Vodovar, D.; Woerther, P.-L.; Hutin, A.; Ghaleh, B.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Amikacin in Patients on Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duceppe, M.-A.; Kanji, S.; Do, A.T.; Ruo, N.; Cavayas, Y.A.; Albert, M.; Robert-Halabi, M.; Zavalkoff, S.; Dupont, P.; Samoukovic, G.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Commonly Used Antimicrobials in Critically Ill Adults During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review. Drugs 2021, 81, 1307–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanberg, P.; Öbrink-Hansen, K.; Thorsted, A.; Bue, M.; Tøttrup, M.; Friberg, L.E.; Hardlei, T.F.; Søballe, K.; Gjedsted, J. Population Pharmacokinetics of Meropenem in Plasma and Subcutis from Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02390-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yang, S.; Hahn, J.; Jang, J.Y.; Min, K.L.; Wi, J.; Chang, M.J. Dose Optimization of Meropenem in Patients on Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Critically Ill Cardiac Patients: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsen, M.; Dreesen, E.; Annaert, P.; Nicolai, J.; Debaveye, Y.; Wauters, J.; Spriet, I. Meropenem Pharmacokinetics and Target Attainment in Critically Ill Patients Are Not Affected by Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Matched Cohort Analysis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewoldt, T.M.J.; Abdulla, A.; Rietdijk, W.J.R.; Muller, A.E.; de Winter, B.C.M.; Hunfeld, N.G.M.; Purmer, I.M.; van Vliet, P.; Wils, E.-J.; Haringman, J.; et al. Model-informed precision dosing of beta-lactam antibiotics and ciprofloxacin in critically ill patients: A multicentre randomised clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1760–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, H.; Roberts, J.A.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Beta-Lactam Antibiotics in Critically Ill Patients. Farm. Hosp. 2022, 46, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jendoubi, A.; Pressiat, C.; De Roux, Q.; Hulin, A.; Ghaleh, B.; Tissier, R.; Kohlhauer, M.; Mongardon, N. The impact of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on antifungal pharmacokinetics: A systematic review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 63, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyster, H.; Shekar, K.; Watt, K.; Reed, A.; Roberts, J.A.; Abdul-Aziz, M.-H. Antifungal Dosing in Critically Ill Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 62, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amphotericin B—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/amphotericin-b (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Amphotericin B Deoxycholate (Conventional): Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/amphotericin-b-deoxycholate-conventional-drug-information (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Kriegl, L.; Hatzl, S.; Schilcher, G.; Zollner-Schwetz, I.; Boyer, J.; Geiger, C.; Hoenigl, M.; Krause, R. Antifungals in Patients with Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Clinical Implications. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Daele, R.; Bekkers, B.; Lindfors, M.; Broman, L.M.; Schauwvlieghe, A.; Rijnders, B.; Hunfeld, N.G.M.; Juffermans, N.P.; Taccone, F.S.; Sousa, C.A.C.; et al. A Large Retrospective Assessment of Voriconazole Exposure in Patients Treated with Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Gu, S.; Huang, L.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, C. Impact of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on voriconazole plasma concentrations: A retrospective study. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 972585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, M.; Llop-Talaveron, J.M.; Fuset, M.; Leiva, E.; Shaw, E.; Gumucio-Sanguino, V.D.; Diez, Y.; Colom, H.; Rigo-Bonnin, R.; Puig-Asensio, M.; et al. Voriconazole Pharmacokinetics in Critically Ill Patients and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support: A Retrospective Comparative Case-Control Study. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, C.A.; Fuge, J.; Grote-Koska, D.; Brand, K.; Slevogt, H.; Cornberg, M.; Simon, S.; Joean, O.; Welte, T.; Rademacher, J. Factors influencing voriconazole plasma level in intensive care patients. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, K.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Cheng, V.; Burrows, F.; Buscher, H.; Cho, Y.-J.; Corley, A.; Diehl, A.; Gilder, E.; Jakob, S.M.; et al. Antimicrobial Exposures in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, P.; Milakovic, D.; Kovacevic, T.; Barisic, V.; Dragic, S.; Zlojutro, B.; Miljkovic, B.; Vucicevic, K.; Rizwan, Z. Thrombocytopenia risks in ARDS COVID-19 patients treated with high-dose linezolid during vvECMO therapy: An observational study. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 7747–7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R. Pharmacokinetic variability and significance of therapeutic drug monitoring for broad-spectrum antimicrobials in critically ill patients. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linezolid—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/linezolid (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Linezolid: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/linezolid-drug-information (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Hahn, J.; Choi, J.H.; Chang, M.J. Pharmacokinetic changes of antibiotic, antiviral, antituberculosis and antifungal agents during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill adult patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, G.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhan, Q.; et al. Influence of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in lung transplant recipients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2020, 45, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Burrows, F.; Buscher, H.; Cho, Y.-J.; Corley, A.; Diehl, A.; Gilder, E.; Jakob, S.M.; Kim, H.-S.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Vancomycin in Critically Ill Adult Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (an ASAP ECMO Study). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e01377-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre, A.; Giglio, A.; Zylbersztajn, B.; Valenzuela, R.; Jan, N.V.S.; Fajardo, C.; Reccius, A.; Dreyse, J.; Hasbun, P. Analysis of Vancomycin Dosage and Plasma Levels in Critically Ill Adult Patients Requiring Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO). J. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 39, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Yang, J.H.; Park, H.J.; In, Y.W.; Lee, Y.M.; Cho, Y.H.; Chung, C.R.; Park, C.-M.; Jeon, K.; Suh, G.Y. Trough Concentrations of Vancomycin in Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, H.S. Prospective Cohort Study of Population Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamic Target Attainment of Vancomycin in Adults on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02408-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Wang, W.-C.; Roan, J.-N.; Luo, C.-Y.; Chou, C.-H. Population Pharmacokinetics of Vancomycin in Intensive Care Patients with the Time-Varying Status of Temporary Mechanical Circulatory Support or Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2024, 13, 2617–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marella, P.; Roberts, J.; Hay, K.; Shekar, K. Effectiveness of Vancomycin Dosing Guided by Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Adult Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01179-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelmaier, K.; Wiedemann, D.; Lampichler, K.; Toth, D.; Galli, L.; Haberl, T.; Steinlechner, B.; Heinz, G.; Laufer, G.; Lang, I.M.; et al. Interdependence of VA-ECMO output, pulmonary congestion and outcome after cardiac surgery. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 81, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torbic, H.; Hohlfelder, B.; Krishnan, S.; Tonelli, A.R. A Review of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Treatment in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Case Series of Adult Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 27, 10742484211069005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacky, A.; Rudiger, A.; Krüger, B.; Wilhelm, M.J.; Paal, S.; Seifert, B.; Spahn, D.R.; Bettex, D. Comparison of Levosimendan and Milrinone for ECLS Weaning in Patients After Cardiac Surgery—A Retrospective Before-and-After Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.I.; Seelhammer, T.G.; Saddoughi, S.A.; Finch, A.S.; Park, J.G.; Wieruszewski, P.M. Cumulative epinephrine dose during cardiac arrest and neurologic outcome after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 80, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massart, N.; Mansour, A.; Ross, J.T.; Ecoffey, C.; Aninat, C.; Verhoye, J.; Launey, Y.; Tadie, J.; Auffret, V.; Flecher, E.; et al. Epinephrine administration in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients is associated with mortality: A retrospective cohort study. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 2899–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L. Factors Influencing Successful Weaning from Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2024, 38, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajter, J.; Volod, O. Anticoagulation Management During ECMO: Narrative Review. JHLT Open 2025, 8, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, I.; Powley, T.R.; Yang, C.G.; Kurlansky, P.A.; Sutherland, L.D.; Hastie, J.M.; Kaku, Y.; Fried, J.A.; Takeda, K. Unfractionated heparin monitoring by anti-factor Xa versus activated partial thromboplastin time strategies during venoarterial extracorporeal life support. Perfusion 2024, 40, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Han, X.; Song, K.; Xing, J. A Comparison of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time and Activated Coagulation Time for Anticoagulation Monitoring during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Therapy. Hamostaseologie 2023, 43, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, A.; Roeleveld, P.P.; Labarinas, S.; Cyrus, J.W.; A Muszynski, J.; E Nellis, M.; Karam, O. Anti-Xa versus time-guided anticoagulation strategies in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Perfusion 2021, 36, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, R.C.; Taylor, A.N.; Cato, A.W.; Patel, V.S.; Waller, J.L.; Wayne, N.B. Low Versus Standard Intensity Heparin Protocols in Adults Maintained on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Pharm. Pract. 2025, 38, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanoiselée, J.; Mourer, J.; Jungling, M.; Molliex, S.; Thellier, L.; Tabareau, J.; Jeanpierre, E.; Robin, E.; Susen, S.; Tavernier, B.; et al. Heparin Dosing Regimen Optimization in Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Pharmacokinetic Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegele, M.; Laxar, D.; Schaden, E.; Baierl, A.; Maleczek, M.; Knöbl, P.; Hermann, M.; Hermann, A.; Zauner, C.; Gratz, J. Subcutaneous Enoxaparin for Systemic Anticoagulation of COVID-19 Patients During Extracorporeal Life Support. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 879425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durila, M.; Vajter, J.; Garaj, M.; Berousek, J.; Lischke, R.; Hlavacek, M.; Vymazal, T. Intravenous enoxaparin guided by anti-Xa in venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A retrospective, single-center study. Artif. Organs 2025, 49, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, D.; Martinez, J.; Bushman, G.; Wolowich, W.R. Anticoagulation strategies in COVID-19 infected patients receiving ECMO support. J. Extra Corpor. Technol. 2023, 55, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, U. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia complicating extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: Review of the literature and alternative anticoagulants. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocuronium—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/rocuronium (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Rocuronium: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rocuronium-drug-information (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Bakdach, D.; Elajez, R.; Bakdach, A.R.; Awaisu, A.; De Pascale, G.; Ait Hssain, A. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Dosing Considerations of Novel β-Lactams and β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitors in Critically Ill Adult Patients: Focus on Obesity, Augmented Renal Clearance, Renal Replacement Therapies, and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Bellomo, R.; Cotta, M.O.; Koch, B.C.P.; Lyster, H.; Ostermann, M.; Roger, C.; Shekar, K.; Watt, K.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H. Machines that help machines to help patients: Optimising antimicrobial dosing in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and renal replacement therapy using dosing software. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1338–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanell-Fernández, M. Echinocandins Pharmacokinetics: A Comprehensive Review of Micafungin, Caspofungin, Anidulafungin, and Rezafungin Population Pharmacokinetic Models and Dose Optimization in Special Populations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitz, G.J.; Murry, D.J. The Influence of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation on Antibiotic Pharmacokinetics. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellmann, R.; Smuszkiewicz, P. Pharmacokinetics of antifungal drugs: Practical implications for optimized treatment of patients. Infection 2017, 45, 737–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, T.X.; Peña, D.; Landau, J.; Nagpal, A.D. Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Adults with Septic Shock: Hope or Hype? Can. J. Cardiol. 2025, 41, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browder, K.; Wanek, M.; Wang, L.; Hohlfelder, B. Opioid and sedative requirements in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients on hydromorphone versus fentanyl. Artif. Organs 2022, 46, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, J.; Pausch, A.; Schaden, E.; Baierl, A.; Jaksch, P.; Erhart, F.; Hoetzenecker, K.; Wiegele, M. Low molecular weight heparin versus unfractioned heparin for anticoagulation during perioperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A single center experience in 102 lung transplant patients. Artif. Organs 2020, 44, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelhammer, T.G.; Bohman, J.K.; Schulte, P.J.; Hanson, A.C.; Aganga, D.O. Comparison of Bivalirudin Versus Heparin for Maintenance Systemic Anticoagulation During Adult and Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.; Dixon, A.A.; Camporota, L.; Barrett, N.A.; Wan, R.Y.Y. Sedation with alfentanil versus fentanyl in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Outcomes from a single-centre retrospective study. Perfusion 2020, 35, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, D.; Drop, J.G.; Wildschut, E.D.; De Hoog, M.; Van Ommen, C.H.; Reis Miranda, D.D. Evaluation of an aPTT guided versus a multimodal heparin monitoring approach in patients on extra corporeal membrane oxygenation: A retrospective cohort study. Perfusion 2025, 40, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtiaud, A.; Petit, M.; Chommeloux, J.; de Chambrun, M.P.; Hekimian, G.; Schmidt, M.; Combes, A.; Luyt, C.-E. Ceftazidime/avibactam serum concentration in patients on ECMO. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Roberts, J.A. Applying Antimicrobial Pharmacokinetic Principles for Complex Patients: Critically Ill Adult Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation and Renal Replacement Therapy. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2021, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J.; Min, K.L.; Kang, S.; Yang, S.; Park, M.S.; Wi, J.; Chang, M.J. Population Pharmacokinetics and Dosing Optimization of Piperacillin-Tazobactam in Critically Ill Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation and the Influence of Concomitant Renal Replacement Therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00633-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kim, H.S.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, D.-H. Population pharmacokinetics of piperacillin/tazobactam in critically ill Korean patients and the effects of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Diehl, A.; Liu, X.; Cheng, V.; Corley, A.; Gilder, E.; Levkovich, B.; McGuinness, S.; Ordonez, J.; Parke, R.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in critically ill patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation—An ASAP ECMO study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01435-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Chen, W.; Cui, G.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, C. Population Pharmacokinetics of Caspofungin among Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Patients during the Postoperative Period of Lung Transplantation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00687-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, B.; Bruce, H.M.; Kershaw, G.; Cai, N.; Othman, J.; Gattas, D.; Robson, J.L.; Hayes, S.; Alicajic, H.; Hines, A.; et al. Hemostasis, coagulation and thrombin in venoarterial and venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: The HECTIC study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicky, P.-H.; Poiraud, J.; Alves, M.; Patrier, J.; D’humières, C.; Lê, M.; Kramer, L.; de Montmollin, É.; Massias, L.; Armand-Lefèvre, L.; et al. Cefiderocol Treatment for Severe Infections due to Difficult-to-Treat-Resistant Non-Fermentative Gram-Negative Bacilli in ICU Patients: A Case Series and Narrative Literature Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadello, K.; Antonucci, E.; Cristallini, S.; Roberts, J.A.; Beumier, M.; Scolletta, S.; Jacobs, F.; Rondelet, B.; de Backer, D.; Vincent, J.-L.; et al. β-Lactam pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy: A case–control study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Shen, L.-J.; Hsu, L.-F.; Ko, W.-J.; Wu, F.-L.L. Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2016, 115, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphine: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/morphine-drug-information (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Fentanyl: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/fentanyl-drug-information (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Ketamine Hydrochloride: Drug Monograph. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Corporation. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Propofol: Drug Monograph. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Corporation. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Propofol—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/propofol#GUID-90662F81-10CE-4078-975F-6BE74A45E314__CITE27 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Midazolam Hydrochloride—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/midazolam-hydrochloride#GUID-A38DF5DC-F52E-4239-9BA9-63A5F2D1A443 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Amikacin—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/amikacin#GUID-B5DAEC1F-0F93-4ED4-865D-B36C7D79692D (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Amikacin Sulfate: Drug Monograph. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Corporation. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kühn, D.; Metz, C.; Seiler, F.; Wehrfritz, H.; Roth, S.; Alqudrah, M.; Becker, A.; Bracht, H.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Hoffmann, M.; et al. Antibiotic therapeutic drug monitoring in intensive care patients treated with different modalities of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and renal replacement therapy: A prospective, observational single-center study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, J.; Heath, T.; Watt, K. Pharmacokinetics and Dosing of Anti-infective Drugs in Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Review of the Current Literature. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 1976–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Ertapenem Sodium: Drug Monograph. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Corporation. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Ertapenem—DynaMed, n.d. Available online: https://www.dynamed.com/drug-monograph/ertapenem#GUID-9DD6A5DF-192E-4EA0-9D84-4C136B11DE92 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Ertapenem: Drug Information—UpToDate, n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ertapenem-drug-information (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Cheng, V.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Burrows, F.; Buscher, H.; Cho, Y.-J.; Corley, A.; Diehl, A.; Gilder, E.; Jakob, S.M.; Kim, H.-S.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Piperacillin and Tazobactam in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: An ASAP ECMO Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e01438-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillâtre, P.; Lemaitre, F.; Nesseler, N.; Schmidt, M.; Besset, S.; Launey, Y.; Maamar, A.; Daufresne, P.; Flecher, E.; Le Tulzo, Y.; et al. Impact of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support on piperacillin exposure in septic patients: A case–control study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, E.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Cheng, V.; Burrows, F.; Buscher, H.; Corley, A.; Diehl, A.; Gilder, E.; Levkovich, B.J.; McGuinness, S.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in critically ill patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and continuous renal replacement therapy: An ASAP ECMO study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e01201-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Wiersema, U.F.; Bihari, S.; Roxby, D. Discordance between ROTEM® clotting time and conventional tests during unfractionated heparin–based anticoagulation in intensive care patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2016, 44, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micromedex® (Electronic Version). Rocuronium Bromide: Drug Monograph. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Corporation. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).