Detection of Problems Related to Hormonal Contraceptives in Community Pharmacy: Application of a Structured Questionnaire in Women of Childbearing Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2.3. Variables Collected

2.2.4. Instruments and Resources Used

- − Sociodemographic profile, 7 questions;

- − Pharmacotherapy in contraception, 8 questions;

- − Cardiovascular risk factors, 5 questions;

- − Treatment adherence: 5 questions.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profile

3.2. Pharmacotherapy in Contraception

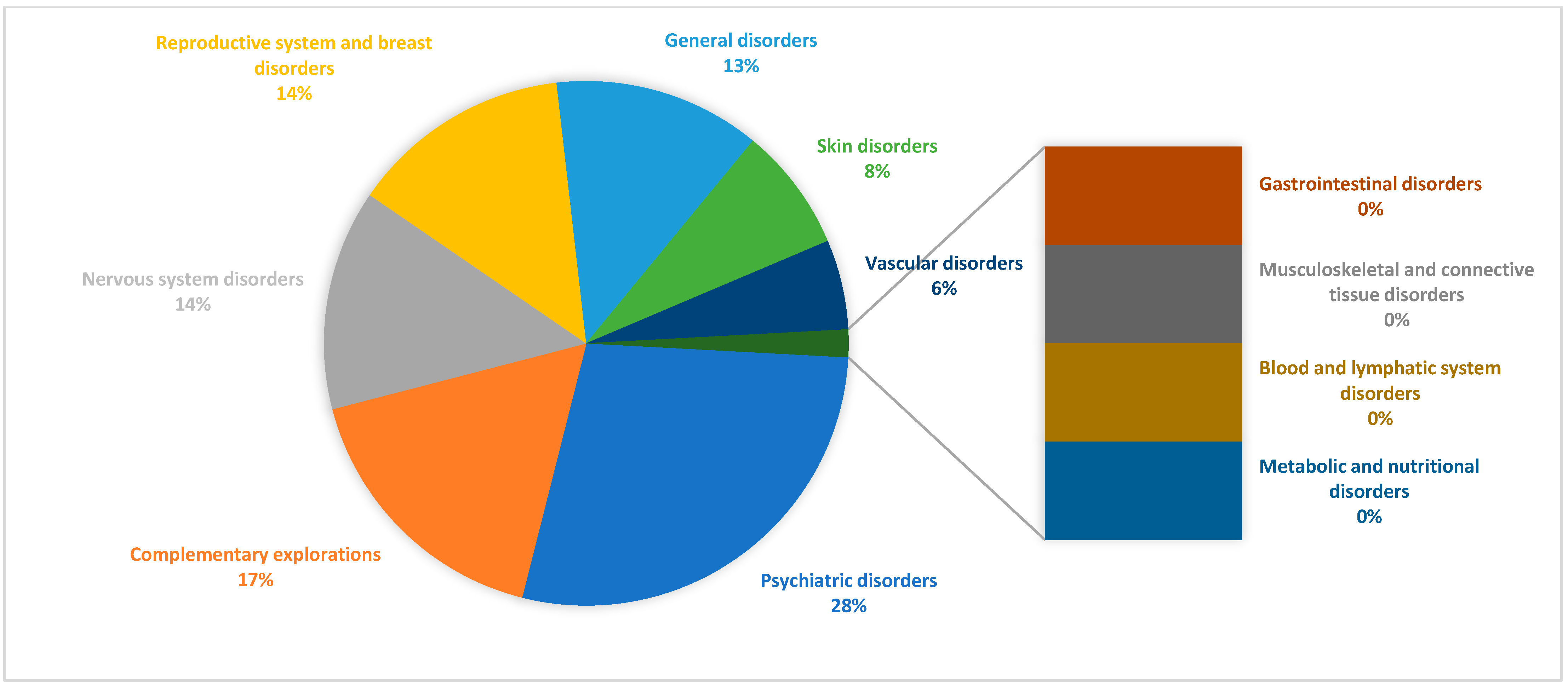

3.3. Adverse Reactions, Treatment Adherence, and Emergency Contraception

3.4. Chronic Conditions

3.5. Blood Pressure

3.6. Smoking

3.7. Obesity

3.8. Chronic Medication Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COC | Combined Oral Contraceptive |

| LARC | Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive |

| DRP | Drug-Related Problem |

| NOM | Negative Outcome associated with Medication |

| IUD | Intrauterine Device |

| PCA | Personalized Care Area |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification |

References

- Sociedad Española de Contracepción. Encuesta Nacional Sobre Anticoncepción en España 2024; SEC: Madrid, Spain, 2024. Available online: https://sec.es/encuesta-de-anticoncepcion-en-espana-2024/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Yeh, P.T.; Kautsar, H.; Kennedy, C.E.; Gaffield, M.E. Values and preferences for contraception: A global systematic review. Contraception 2022, 111, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, J.T.; Ross, J.; Sullivan, T.M.; Hardee, K.; Shelton, J.D. Contraceptive method mix: Updates and implications. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2020, 8, 666–679. Available online: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/ghsp/8/4/666.full.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ti, A.; Soin, K.; Rahman, T.; Dam, A.; Yeh, P.T. Contraceptive values and preferences of adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Contraception 2022, 111, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelingh Bennink, H.J.; van Gennip, F.A.; Gerrits, M.G.; Egberts, J.F.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Kopp-Kallner, H. Health benefits of combined oral contraceptives—a narrative review. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2024, 29, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Información Terapéutica Sobre Anticoncepción Hormonal; MSCBS: Madrid, Spain, 1997. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/infMedic/porVolumen/anticonc.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Foro de Atención Farmacéutica-Farmacia Comunitaria. Guía Práctica Para Los Servicios Profesionales Farmacéuticos Asistenciales Desde la Farmacia Comunitaria; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.farmaceuticos.com/farmaceuticos/farmacia/farmacia-asistencial/foro-de-atencion-farmaceutica/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Barrera Coello, L.; Olvera Rodríguez, V.; Castelo-Branco Flores, C.; Cancelo Hidalgo, M.D.J. Causas de desapego a los métodos anticonceptivos. Ginecol. Obstet. México 2019, 87, 128–135. Available online: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/138425/1/690779.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Le Guen, M.; Schantz, C.; Régnier-Loilier, A.; de La Rochebrochard, E. Reasons for rejecting hormonal contraception in Western countries: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114247. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953621005797 (accessed on 8 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, J.R.; Marthey, D.; Xie, L.; Boudreaux, M. Contraceptive method type and satisfaction, confidence in use, and switching intentions. Contraception 2021, 104, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, A.; Jensen, J.T.; Brown, J.; Thomas, M.; Archer, D.F.; Schreiber, C.A.; Teal, S.; Westhoff, C.; Dart, C.; Blithe, D.L. Emergency contraception for individuals weighing 80 kg or greater: A randomized trial of 30 mg ulipristal acetate and 1.5 mg or 3.0 mg levonorgestrel. Contraception 2024, 137, 110474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambrina, A.M.; Rius, P.; Gascón, P.; Armelles, M.; Camps-Bossacoma, M.; Franch, À.; Rabanal, M. Characterization of the use of emergency contraception from sentinel pharmacies in a region of southern Europe. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.; Le, H.; Dinh, X. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward emergency contraceptive pills among community pharmacists and pharmacy customers: A cross-sectional study in urban Vietnam. Contraception 2023, 128, 110275. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010782423003736 (accessed on 18 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewska, A.; Walędziak, M.; Merks, P.; Różańska-Walędziak, A. Emergency contraception—A narrative review of literature. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 299, 188–192. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38880026/ (accessed on 18 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Emergency Contraception [Internet]; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/emergency-contraception (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Leelakanok, N.; Methaneethorn, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the adverse effects of levonorgestrel emergency oral contraceptive. Clin. Drug Investig. 2020, 40, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Savio, M.C.; Sammarini, M.; Facchinetti, F.; Grandi, G. Contraception and Cardiovascular Diseases. Female Male Contracept; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-70932-7_17 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Rosano, G.; Rodriguez-Martinez, M.A.; Spoletini, I.; Regidor, P.A. Obesity and contraceptive use: Impact on cardiovascular risk. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 3761–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houvèssou, G.M.; Farías-Antúnez, S.; da Silveira, M.F. Combined hormonal contraceptives use among women with contraindications according to the WHO criteria: A systematic review. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2021, 27, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, N.A.; Blyler, C.A.; Bello, N.A. Oral contraceptive pills and hypertension: A review of current evidence and recommendations. Hypertension 2023, 80, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.V.; Köhler-Forsberg, K.; Dam, V.H.; Poulsen, A.S.; Svarer, C.; Jensen, P.S.; Knudsen, G.M.; Fisher, P.M.; Ozenne, B.; Frokjaer, V.G. Oral contraceptives and the serotonin 4 receptor: A molecular brain imaging study in healthy women. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczyk, F.Z.; McGough, A.; Chagam, L.; Sitruk-Ware, R. Metabolism of progestogens used for contraception and menopausal hormone therapy. Steroids 2024, 207, 109427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, J.A.; Hayashi, K. Progesterone actions and resistance in gynecological disorders. Cells 2022, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Bot Plus [Internet]; CGCOF: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://www.farmaceuticos.com/botplus/que-es-botplus/ (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS). CIMA: Centro de Información de Medicamentos Madrid; AEMPS: Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/publico/home.html (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Ridgeway, K.; Montgomery, E.T.; Smith, K.; Torjesen, K.; van der Straten, A.; Achilles, S.L.; Griffin, J.B. Vaginal ring acceptability: A systematic review and meta-analysis of vaginal ring experiences from around the world. Contraception 2022, 106, 16–33. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010782421004108 (accessed on 21 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, R.F.; Prata, N. Hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels in women using copper-releasing or levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices: A systematic review. Contraception 2013, 87, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, E.M.; Folger, S.G.; Jeng, G.; Jamieson, D.J.; Curtis, K.M. Treatment of bleeding irregularities in women with copper-containing IUDs: A systematic review. Contraception 2013, 87, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Larios, F.; Llamazares, M.J.A.; Reisen, H.M.; Ribes, I.P.; Novoa, M.R.; Lahoz-Pascual, I. Impact of the hands-on clinical training program for subdermic implant on contraceptive counseling and users’ choice in Spain: A 6-month follow-up study. Contraception 2024, 132, 110372. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010782424000118 (accessed on 15 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Young, H.N.; Pathan, F.S.; Hudson, S.; Mott, D.; Smith, P.D.; Schellhase, K.G. Impact of patient-centered prescription medication labels on adherence in community pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.J.; Arribas, L. Guía de Práctica Clínica de Anticoncepción Hormonal e Intrauterina; Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud (IACS): Zaragoza, Spain, 2019; Guía Salud; Available online: https://portal.guiasalud.es/gpc/anticoncepcion/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Kutlu, Ö.; Karadağ, A.S.; Wollina, U. Adult acne versus adolescent acne: A narrative review with a focus on epidemiology to treatment. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2023, 98, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, R.S.; Lo, S.S. Are women ready for more liberal delivery of emergency contraceptive pills? Contraception 2005, 71, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Contracepción. Guía Práctica en Anticoncepción Oral: Basada en la Evidencia [Internet]; SEC: Madrid, Spain, 2003. Available online: https://hosting.sec.es/descargas/AH_2003_GuiaPracticaAnticOral.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Martínez, F.; Faus, M.J. Guía de Utilización de Medicamentos: Anticonceptivos Hormonales [Internet]; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/33077 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Benardete-Harari, D.N.; Navarro-Gerrard, C.; Meraz-Ávila, D.; Alkon-Meadows, T.; Nellen-Hummel, H.; Halabe-Cherem, J. Anticonceptivos hormonales y alteración de las pruebas de la función tiroidea. Med. Interna Mex. 2015, 31, 590–595. Available online: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/medintmex/mim-2015/mim155l.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Johansson, T.; Larsen, S.V.; Bui, M.; Ek, W.E.; Karlsson, T.; Johansson, Å. Population-based cohort study of oral contraceptive use and risk of depression. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2023, 32, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Bashar, M.A.; Bazhair, R.M.; Abdurahman, D.O.; Alrehaili, R.A.; Ennahoui, M.E.; Alsulaiman, Y.S.; Alamri, S.D.; Mohamed, E.F. Association of hormonal contraceptives with depression among women in reproductive age groups: A cross-sectional analytic study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2024, 2024, 7309041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehlendorf, C.; Rodriguez, M.I.; Levy, K.; Borrero, S.; Steinauer, J. Disparities in family planning. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Muñoz, D.; Pérez, G.; Garcia-Subirats, I.; Díez, E. Social and economic inequalities in the use of contraception among women in Spain. J. Women’s Health 2011, 20, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sociedad Andaluza de Contracepción (SAC); Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC); Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN). Guía de Anticoncepción y Salud Sexual en Atención Primaria; semFYC ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://www.samfyc.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Anticoncepcion_y_SS_2021_SAMFyC_SAC_SEMERGEN_bbb.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ensuring Human Rights in the Provision of Contraceptive Information and Services: Guidance and Recommendations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506748 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Jokanovic, N.; Tan, E.C.; Sudhakaran, S.; Kirkpatrick, C.M.; Dooley, M.J.; Ryan-Atwood, T.E.; Bell, J.S. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: An overview of systematic reviews. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 661–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Marital Status | Contraception | Therapeutic Indication/Pathology | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With partner | 102 (32.27%) | 116 (36.70%) | Acne | 21 (6.64%) | 0.01 |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 61 (19.30%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 33 (10.44%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 1 (0.31%) | ||||

| Without partner | 30 (9.49%) | 68 (21.51%) | Acne | 7 (2.21%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 37 (11.70%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 18 (5.69%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 6 (1.89%) | ||||

| Age | Contraception | Pathology | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 years | 7 (2.21%) | 18 (5.69%) | Acne | 3 (0.94%) | 0.00001 |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 10 (3.16%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 4 (1.26%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 1 (0.31%) | ||||

| 21–28 years (inclusive) | 52 (16.45%) | 115 (36.39%) | Acne | 12 (3.79%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 62 (19.62%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 38 (12.02%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 3 (0.94%) | ||||

| 29–35 years (inclusive) | 41 (12.97%) | 27 (8.54%) | Acne | 11 (3.48%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 11 (3.48%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 3 (0.94%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 2 (0.63%) | ||||

| ≥36 years | 32 (10.12%) | 24 (7.59%) | Acne | 2 (0.63%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 15 (4.74%) | ||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 6 (1.89%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 1 (0.31%) | ||||

| Pharmaceutical Form/Indication | Contraception | Therapeutic Indication/Pathology | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral form | 78 (24.68%) | COC | 150 (47,46%) | Acne | 21 (6.64%) | 0.00002 | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 87 (27.53%) | ||||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 39 (12.34%) | ||||||

| Endometriosis | 3 (0.94%) | ||||||

| Non-oral form | 54 (17.08%) | IUD | 17 (5.37%) | 34 (10, 75%) | Acne | 6 (1.89%) | |

| Vaginal delivery system (vaginal ring) | 27 (8.54%) | Menstrual cycle regulation | 17 (5.37%) | ||||

| Subcutaneous implant | 10 (3.16%) | Polycystic ovary syndrome | 8 (2.53%) | ||||

| Endometriosis | 3 (0.94%) | ||||||

| Anaemia/IUD Use | With Anaemia Episodes | Without Anaemia Episodes | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of an IUD | 16 (5.06%) | 130 (41.13%) | 0.22 |

| Use of a contraceptive method other than an IUD | 11 (3.48%) | 156 (49.36%) |

| Prescriber | Indication for the Use of the Contraceptive Method | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Dermatologist | Acne | 2 (0.63%) |

| Gynaecology | Acne | 8 (2.56%) |

| Endometriosis | 5 (1.58%) | |

| Pregnancy prevention | 88 (27.84%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 79 (25.00%) | |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 37 (11.70%) | |

| Matron | Pregnancy prevention | 5 (1.58%) |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Primary Care Physician | Acne | 6 (1.89%) |

| Pregnancy prevention | 41 (12.97%) | |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 24 (7.59%) | |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 7 (2.21%) | |

| Pharmacist | Pregnancy prevention | 2 (0.63%) |

| None (Self-medication) | Pregnancy prevention | 7 (2.21%) |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 2 (0.63%) |

| Adverse Reactions/Therapeutic Adherence | Presence of Adverse Reactions | Lack of Adverse Reactions | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Adherence | 93 (29.43%) | 82 (25.94%) | 0.02 |

| Lack of therapeutic Adherence | 56 (17.72%) | 85 (26.89%) |

| Therapeutic Adherence/Pharmaceutical Form | Oral Pharmaceutical Form (COC) | Other Pharmaceutical Forms | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic adherence | 137 (43.35%) | 75 (22.15%) | IUD | 21 (6.64%) | 0.00003 |

| Vaginal Delivery System (vaginal ring) | 43 (13.60%) | ||||

| Subcutaneous Implant | 11 (3.48%) | ||||

| Lack of therapeutic adherence | 91 (28.79%) | 13 (2.84%) | IUD | 6 (1.89%) | |

| Vaginal Delivery System (vaginal ring) | 6 (1.89%) | ||||

| Subcutaneous Implant | 1 (0.31%) | ||||

| Physiological System | Pathology | No. of Women (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory system | Asthma | 9 (2.84%) |

| Allergy | 5 (1.58%) | |

| Endocrine system | Hypothyroidism | 11 (3.48%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Cardiovascular system | Arterial hypertension | 6 (1.89%) |

| Partial obstruction of the right bundle branch | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Arrhythmias | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Long QT syndrome | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Blood and lymphatic system | “Clotting disorders” | 1 (0.31%) |

| Anaemia | 2 (0.63%) | |

| Haemophilia | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Factor V Leiden syndrome | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Thalassaemia | 2 (0.63%) | |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Nervous system | Migraine | 3 (0.94%) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Glaucoma | 2 (0.63%) | |

| Psychiatric | Anxiety and depression | 4 (1.26%) |

| Digestive system | Irritable bowel syndrome | 2 (0.63%) |

| Nonspecific terminal ileitis | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Immune system | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (0.63%) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Psoriasis | 1 (0.31%) |

| Alopecia | 1 (0.31%) |

| ATC Group | Classification | Nº of Women |

|---|---|---|

| A: Alimentary tract and metabolism | A02B: Drugs for peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 (0.31%) |

| A03A: Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (0.31%) | |

| A03B: Belladonna and derivatives | 1 (0.31%) | |

| A04A: Antiemetics and antinauseants | 1 (0.31%) | |

| A10B: Blood glucose-lowering drugs, excluding insulins | 1 (0.31%) | |

| A12A: Calcium | 1 (0.31%) | |

| B: Blood and blood-forming organs | B01A: Antithrombotic agents | 1 (0.31%) |

| B03A: Iron preparations | 2 (0.63%) | |

| C: Cardiovascular system | C02A: Centrally acting antiadrenergic agents | 4 (1.26%) |

| C09A: ACE inhibitors | 1 (0.31%) | |

| C09C: Angiotensin II antagonists | 1 (0.31%) | |

| C10A: Lipid-modifying agents | 1 (0.31%) | |

| D: Dermatological | D07A: Topical corticosteroids | 1 (0.31%) |

| D11A: Other dermatological preparations | 1 (0.31%) | |

| G: Genitourinary system and sex hormones | G03D: Progestogens | 1 (0.31%) |

| H: Systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins | H02A: Corticosteroids for systemic use | 3 (0.94%) |

| H03A: Thyroid hormones | 10 (3.16%) | |

| L: Antineoplastic and immunomodulatory agents | L01B: Antimetabolites | 2 (0.63%) |

| L04A: Immunosuppressants | 1 (0.31%) | |

| M: Musculoskeletal system | M01A: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drugs (NSAIDs) | 3 (0.94%) |

| N: Nervous system | N02A: Opioids | 2 (0.63%) |

| N02B: Other analgesics and antipyretics | 1 (0.31%) | |

| N02C: Antimigraine preparations | 2 (0.63%) | |

| N03A: Antiepileptics | 1 (0.31%) | |

| N05B: Anxiolytics | 1 (0.31%) | |

| N05C: Hypnotics and sedatives | 1 (0.31%) | |

| N06A: Antidepressants | 4 (1.26%) | |

| N07A: Parasympathomimetic | 1 (0.31%) | |

| P: Antiparasitic products, insecticides, and repellents | P01B: Antimalarials | 2 (0.63%) |

| R: Respiratory system | R03A: Adrenergic, inhalants | 7 (2.21%) |

| R06A: Antihistamines for systemic use | 6 (1.89%) | |

| S: Sensitive organs | S01E: Antiglaucoma preparations and miotics | 1 (0.31%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sicilia-González, R.; Abdala-Kuri, S.; Morales-Marrero, C.; Peña-Vera, A.; Oliva-Martín, A.; Dévora-Gutiérrez, S. Detection of Problems Related to Hormonal Contraceptives in Community Pharmacy: Application of a Structured Questionnaire in Women of Childbearing Age. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040112

Sicilia-González R, Abdala-Kuri S, Morales-Marrero C, Peña-Vera A, Oliva-Martín A, Dévora-Gutiérrez S. Detection of Problems Related to Hormonal Contraceptives in Community Pharmacy: Application of a Structured Questionnaire in Women of Childbearing Age. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(4):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040112

Chicago/Turabian StyleSicilia-González, Raquel, Susana Abdala-Kuri, Chaxiraxi Morales-Marrero, Adama Peña-Vera, Alexis Oliva-Martín, and Sandra Dévora-Gutiérrez. 2025. "Detection of Problems Related to Hormonal Contraceptives in Community Pharmacy: Application of a Structured Questionnaire in Women of Childbearing Age" Pharmacy 13, no. 4: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040112

APA StyleSicilia-González, R., Abdala-Kuri, S., Morales-Marrero, C., Peña-Vera, A., Oliva-Martín, A., & Dévora-Gutiérrez, S. (2025). Detection of Problems Related to Hormonal Contraceptives in Community Pharmacy: Application of a Structured Questionnaire in Women of Childbearing Age. Pharmacy, 13(4), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040112