Jamaican Community Pharmacists-Determined Barriers to Availability of Smoking Cessation Aids

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objective of This Study

- To determine if Jamaican pharmacists are willing to stock and dispense smoking cessation aids.

- To determine the number of pharmacies in the parishes of Kingston and Saint Andrew that stock cessation aids and the most prevalent option provided.

- To assess the knowledge of Jamaican pharmacists on the range of smoking cessation aids available to support the process.

- To identify the pharmacist-determined barriers to the offering for sale of smoking cessation aids.

- To identify the demographics of patients requesting or using smoking cessation aids.

- To obtain the perceptions of smoking cessation advocates and regulatory authorities on the availability of smoking cessation aids and the involvement of pharmacists in the quitting process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Population and Sampling

- (i)

- The Ministry of Health and Wellness: Non-Communicable Diseases and Injuries Prevention Unit, responsible for NCD risk reduction, health promotion, disease management, surveillance, policy advocacy, and capacity building.

- (ii)

- The National Council on Drug Abuse, which provides information on substance use and promotes treatment and prevention programs.

- (iii)

- The Pharmaceutical Society of Jamaica, advocating for high professional standards, safe medication use, and healthcare cooperation.

- (iv)

- The Medical Association of Jamaica, an advisory body for medical professionals on health sector reform.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Measurement of Variables

2.6. Data Collection and Management

2.7. Reliability and Validity

2.8. Data Analysis

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate, Distribution, Age of Respondents, Years of Experience/Practice

3.2. Knowledge of Cessation Aids

3.3. Inventory/Stocking

3.4. Reasons for Unavailability

3.5. Willingness to Include Cessation Aids in Inventory

3.6. Barriers Impacting the Stocking of Smoking Cessation Aids

3.7. Request for Smoking Cessation Aids (Patients and Medical Doctors)

3.8. Average of Requests for Smoking Cessation Aids

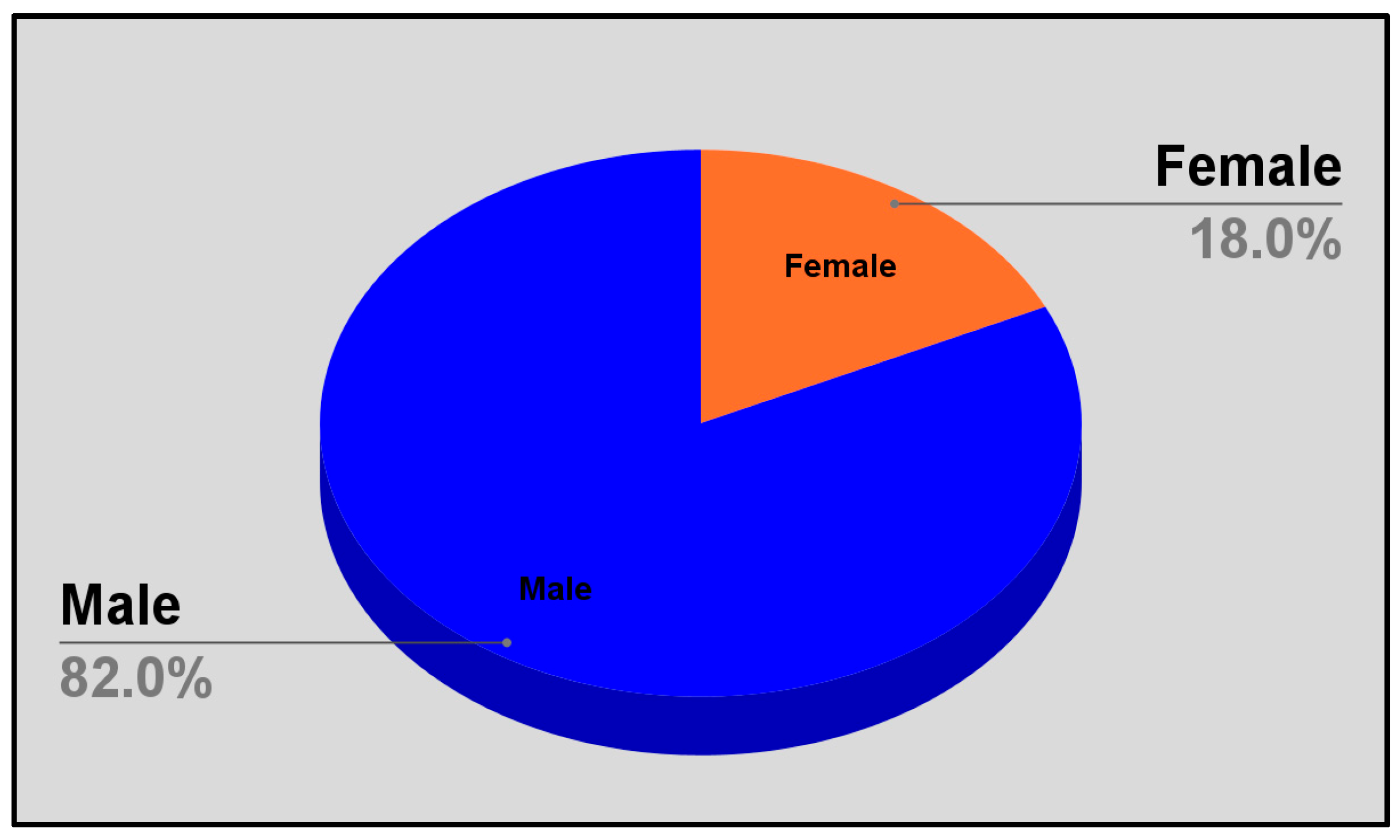

3.9. Gender Distribution of Patients Requesting Cessation Aids

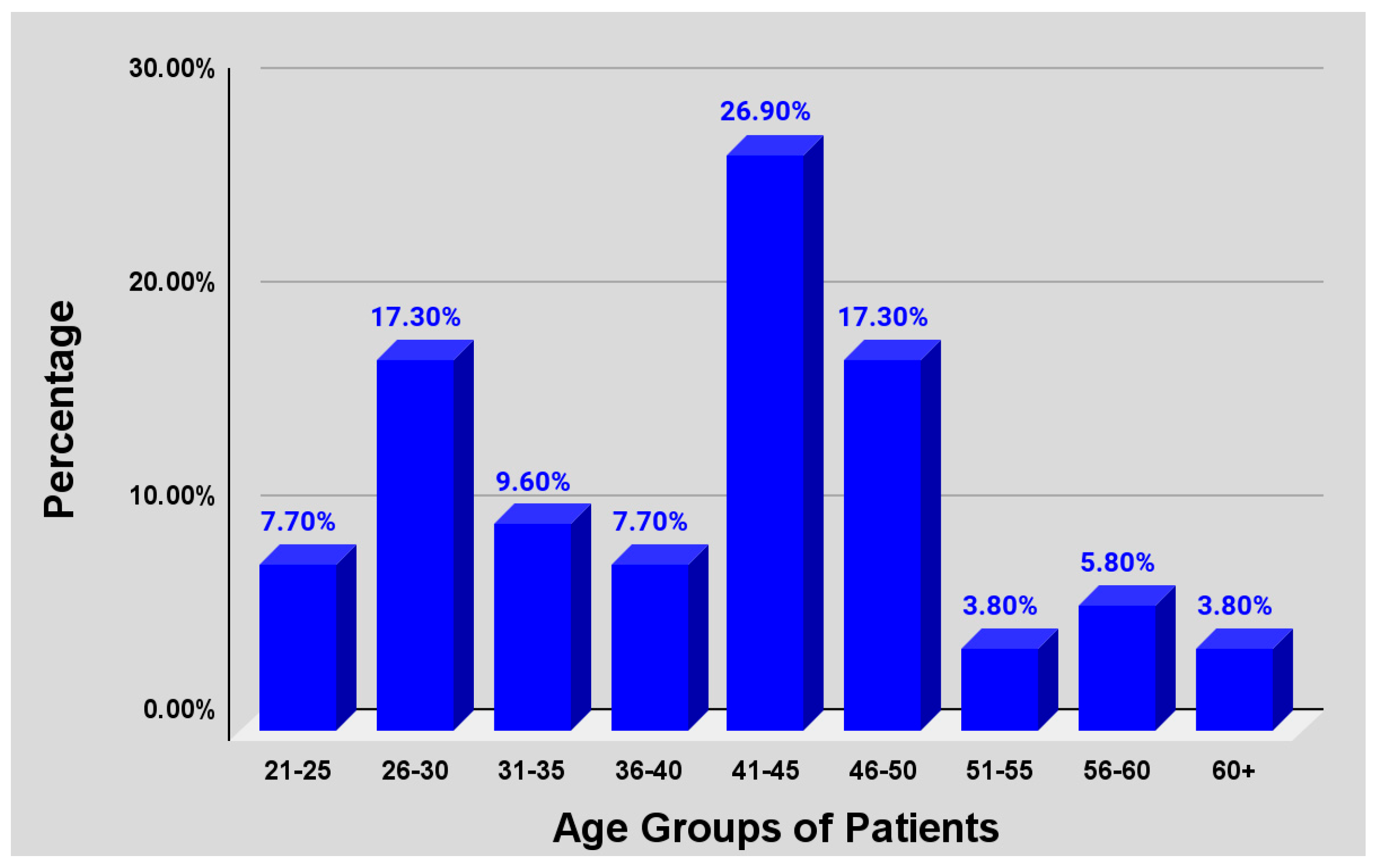

3.10. Age Distribution of Patients Requesting Smoking Cessation Aids

3.11. Bivariate Analysis: Location and Stocking

3.12. Structured Interview Response

3.13. Structured Interview Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Response Rate and Impact of COVID-19

4.2. Willingness to Stock and Dispense Smoking Cessation Aids

4.3. Determination of Stocking Pharmacies and Prevalent Options

4.4. Relative Knowledge and Range of Cessation Aids Available

4.5. Pharmacist-Determined Barriers

4.6. Reported Demographics of Patients Requesting/Using Smoking Cessation Aids

4.7. Perceptions of Smoking Cessation Advocates and Regulatory Authorities

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Liao, L.M.; Reyes-Guzman, C.; Hartge, P.; Caporaso, N.; Freedman, N.D. Association of Long-term, Low-Intensity Smoking With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjartveit, K.; Tverdal, A. Health consequences of smoking 1–4 cigarettes per day. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office on Smoking and Health (US). The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General; Preface from the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK44319/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Kuper, H.; Adami, H.; Boffetta, P. Tobacco use, cancer causation, and public health impact. J. Intern. Med. 2002, 251, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2019. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/data/profiles-ncd (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Abdulkadri, A.; Floyd, S.; Mkrtchyank, I.; Marajh, G.; Gonzales, C.; Cunningham-Myrie, C. Addressing the Adverse Impacts of Non-Communicable Diseases on the Sustainable Development of Caribbean Countries; Studies and Perspectives Series-ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 100 (LC/TS.2021/4-LC/CAR/TS.2021/2); Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC): Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Samuels, T.A.; Unwin, N. The 2007 Caribbean Community Port-of-Spain Declaration on noncommunicable diseases: An overview of a multidisciplinary evaluation. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica Pan Am. J. Public Health 2018, 42, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospedales, C.J.; Barcelo, A.; Luciani, S.; Legetic, B.; Ordunez, P.; Blanco, A. NCD Prevention and Control in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Regional Approach to Policy and Program Development. Glob. Heart 2012, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospedales, C.J.; Samuels, T.A.; Cummings, R.; Gollop, G.; Greene, E. Raising the priority of chronic noncommunicable diseases in the Caribbean. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2011, 30, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Ministry of Health and Wellness. National Screening Guidelines for Priority Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Primary Health Care: MOHW. 2020. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jm/programmes-policies/chronic-non-communicable-diseases/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Goodchild, M.; Nargis, N.; d’Espaignet, E.T. Global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases. Tob. Control 2018, 27, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.V.; McGrowder, D.A.; Barnett, J.D.; McGaw, B.A.; McKenzie, I.F.; James, L.G. Tobacco-related chronic illnesses: A public health concern for Jamaica. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2012, 13, 4733–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchman, S.C.; Fong, G.T.; Zanna, M.P.; Thrasher, J.F.; Chung-Hall, J.; Siahpush, M. Socioeconomic status and smokers’ number of smoking friends: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 143, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Parker, L.A.; Tursan d’Espaignet, E.; Chatterji, S. Socioeconomic Inequality in Smoking in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: Results from the World Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C.; Mollborn, S.; Lawrence, E.M. Life course transitions in early adulthood and SES disparities in tobacco use. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 43, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeary, J.G.; Walcott, G.; Abel, W.; Mitchell, G.; Lalwani, K. Prevalence, perceived risk and associated factors of tobacco use amongst young, middle-aged and older adults: Analysis of a national survey in Jamaica. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, P.; Alleyne, S.G. Effective global tobacco control in the next decade. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. L’Assoc. Med. Can. 2015, 187, 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; MacLennan, M.; Chaloupka, F.J.; Yurekli, A.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Palipudi, K.; Zatońksi, W.; Asma, S.; Gupta, P.C. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, 3rd ed.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 3. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343639/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- WHO. Needs Assessment for Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Jamaica, Convention Secretariat. 2015. Available online: https://moh.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Jamaica-needs-assessment-report_Jan26.2015.FINAL-VERSION.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- The Statistical Institute of Jamaica. End of Year Populations by Parish—Kingston and St. Andrew. Available online: https://statinja.gov.jm/demo_socialstats/EndofYearPopulationbyParish.aspx (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelberg, S.G.; Stanton, J.M. Introduction: Understanding and dealing with organizational survey nonresponse. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draugalis, J.R.; Coons, S.J.; Plaza, C.M. Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method 2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sardana, M.; Tang, Y.; Magnani, J.W.; Ockene, I.S.; Allison, J.J.; Arnold, S.V.; Jones, P.G.; Maddox, T.M.; Virani, S.S.; McManus, D.D. Provider-Level Variation in Smoking Cessation Assistance Provided in the Cardiology Clinics: Insights from the NCDR PINNACLE Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e011307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, C.I.; Aydin, L.Y.; Turker, Y.; Baltaci, D.; Dikici, S.; Sariguzel, Y.C.; Alasan, F.; Deler, M.H.; Karacam, M.S.; Demir, M. Comparison of smoking habits, knowledge, attitudes, and tobacco control interventions between primary care physicians and nurses. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2015, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, D.; Wagena, E.J.; Wesseling, G. Smoking cessation practices of Dutch general practitioners, cardiologists, and lung physicians. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet-Benezech, B.; Champanet, B.; Rouzaud, P. Smoking cessation at the pharmacy: Feasibility and benefits based on a French observational study with six-month follow-up. Subst. Abus. Rehabil. 2018, 17, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condinho, M.; Ramalhinho, I.; Sinogas, C. Smoking cessation at the community pharmacy: Determinants of success from a real-life practice. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.; Thomas, D. Tackling tobacco smoking: Opportunities for pharmacists. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 22, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaybi, M.; Alzahrani, S.S.; Algethmi, A.M.; Alamri, N.S.; Natto, Y.S.; Hashim, S.T.; Altammar, A.; Alzubaidi, A.S.; Alzahrani, I.B.; Alghamdi, A.A. E-cigarettes and Vaping: A Smoking Cessation Method or Another Smoking Innovation? Cureus 2022, 14, e32435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, L.F.; Perera, R.; Bullen, C.; Mant, D.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Cahill, K.; Lancaster, T. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P.; Phillips-Waller, A.; Przulj, D.; Pesola, F.; Myers Smith, K.; Bisal, N.; Li, J.; Parrott, S.; Sasieni, P.; Dawkins, L.; et al. A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rossem, C.; Spigt, M.G.; Kleijsen, J.R.; Hendricx, M.; van Schayck, C.P.; Kotz, D. Smoking cessation in primary care: Exploration of barriers and solutions in current daily practice from the perspective of smokers and healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 21, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, S.; Bancroft, A.; Parry, O.; Amos, A. ‘I came back here and started smoking again’: Perceptions and experiences of quitting among disadvantaged smokers. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.S.; Francis, D.K.; Tulloch-Reid, M.K.; Younger, N.O.; McFarlane, S.R.; Wilks, R.J. An update on the burden of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Jamaica: Findings from the Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey 2007–2008. West Indian Med. J. 2011, 60, 422–428. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Institute of Jamaica. Labour Force Survey. 2024. Available online: https://statinja.gov.jm/LabourForce/NewLFS.aspx (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Ekpu, V.U.; Brown, A.K. The Economic Impact of Smoking and of Reducing Smoking Prevalence: Review of Evidence. Tob. Use Insights 2015, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.R.; Stead, L.F.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Cahill, K.; Lancaster, T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, L.A.; Harris, K.J.; Noonan, C.W. Randomized trial assessing the effectiveness of a pharmacist-delivered program for smoking cessation. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Bachyrycz, A.; Anderson, J.R.; Tinker, D.; Raisch, D.W. Quitting patterns and predictors of success among participants in a tobacco cessation program provided by pharmacists in New Mexico. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2014, 20, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, H.K.; Bond, C.M.; Lennox, A.S.; Silcock, J.; Winfield, A.J. Knowledge of and attitudes to smoking cessation: The effect of stage of change training for community pharmacy staff. Health Bull. 1998, 56, 526–539. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, T.A.; McElnay, J.C.; Drummond, A. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention based in community pharmacies. Addiction 2001, 96, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.J.; Hudmon, K.S. Pharmacist prescriptive authority for smoking cessation medications in the United States. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. JAPhA 2018, 58, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudd, T.R. Emerging role of pharmacists in managing patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. AJHP Off. J. Am. Soc. Health-Syst. Pharmacists 2020, 77, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, V.H.; Stead, L.F. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 1, CD001188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inch, J.; Bond, C.M.; Blenkinsopp, A.; Celino, G. Progress in implementing the community pharmacy contractual framework: Provision of essential and enhanced services. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2007, 15, B50. [Google Scholar]

- Noyce, P.R. Providing patient care through community pharmacies in the UK: Policy, practice, and research. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007, 41, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age Group Distribution | Percent |

|---|---|

| 26–30 | 22.8 |

| 31–35 | 12.3 |

| 36–40 | 7.0 |

| 41–45 | 15.8 |

| 46–50 | 10.5 |

| 51–55 | 12.3 |

| 56–60 | 3.5 |

| 61 and over | 15.8 |

| Years of Pharmacy Practice | Percent |

|---|---|

| 1–5 | 28.1 |

| 6–10 | 8.8 |

| 11–15 | 10.5 |

| 16–20 | 14.0 |

| 21–25 | 12.3 |

| 26–30 | 8.8 |

| 31 and over | 17.5 |

| Parishes | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingston | St. Andrew | |||||

| Do you stock smoking cessation aids in your pharmacy? | Yes | 86% | (6) | 14% | (1) | 7 |

| No | 44% | (22) | 56% | (28) | 50 | |

| Total | 49% | (28) | 51% | (29) | 57 | |

| Major Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Smoking is a contributing factor of NCDs | Large percent of deaths worldwide as a result of NCDs |

| Risk factors include tobacco use | |

| Smoking is a risk factor | |

| Noteworthy prevalence of tobacco use exists in Jamaica | |

| Implementation of strategies to mitigate use | Availability of tobacco cessation aids |

| Drug counseling | |

| These strategies are offered island-wide | |

| Referral partnerships | Clients with dual diagnosis referral to physician required |

| Strong advocacy for the use of smoking cessation aids | Preference towards encouraging non-nicotine aids |

| Use of regulated cessation aids offered by trained providers | |

| Support for any kind of cessation aids | |

| Advocacy for the use of cessation aids | |

| Link between encouraging the use of cessation aids and attaining healthy lifestyle | |

| Negative effects of smoking such as organ damage | |

| Advocates the offering of cessation aids | |

| Importance of screening for smoking habits | Disclosure of smoking habits dictates treatment plan |

| Disclosure facilitates best possible health outcome for patient | |

| Screening and disclosure of information is inter-related with care and information provided by pharmacists | |

| Utility of cessation aids | Cessation aids are important in quitting process |

| The impact of cessation aids is predicated on the patient’s willingness to change | |

| Change requires patient education and knowledge of the impact of smoking | |

| Barriers | Cost |

| Availability | |

| Accessible through prescription only | |

| Need for the strengthening of training for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals | |

| Competency of health practitioners to screen patients adequately | |

| The role of pharmacists in the quitting process | It is important that they interact with patients on a frequent basis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langlay, A.; Abrons, J.; Daly, A. Jamaican Community Pharmacists-Determined Barriers to Availability of Smoking Cessation Aids. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030081

Langlay A, Abrons J, Daly A. Jamaican Community Pharmacists-Determined Barriers to Availability of Smoking Cessation Aids. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(3):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030081

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanglay, Aleena, Jeanine Abrons, and Andrea Daly. 2025. "Jamaican Community Pharmacists-Determined Barriers to Availability of Smoking Cessation Aids" Pharmacy 13, no. 3: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030081

APA StyleLanglay, A., Abrons, J., & Daly, A. (2025). Jamaican Community Pharmacists-Determined Barriers to Availability of Smoking Cessation Aids. Pharmacy, 13(3), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030081