SMART Pharmacist—The Impact of Education on Improving Pharmacists’ Participation in Monitoring the Safety of Medicine Use in Montenegro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

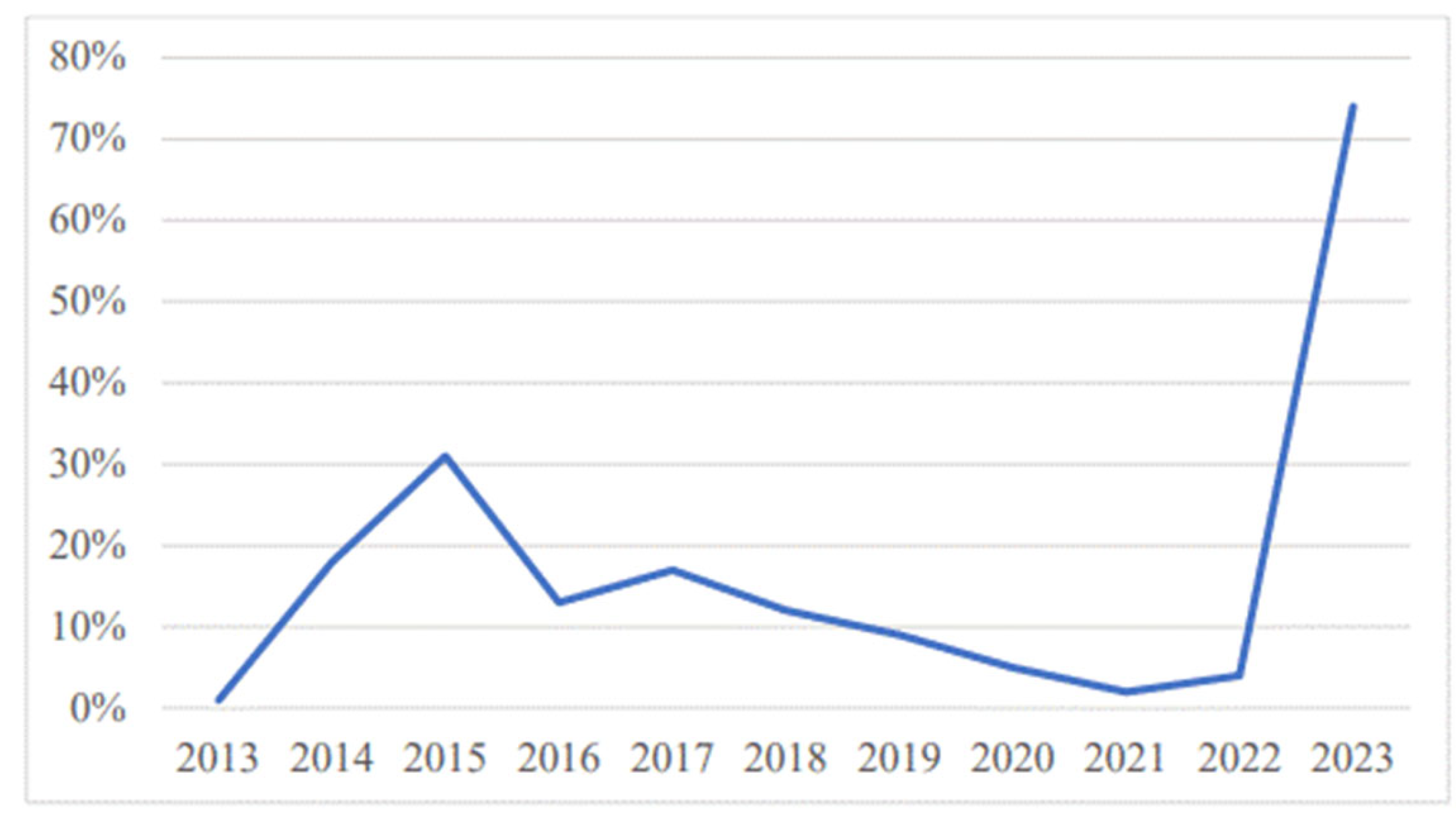

3. Results

3.1. The Severity of the Adverse Drug Reactions

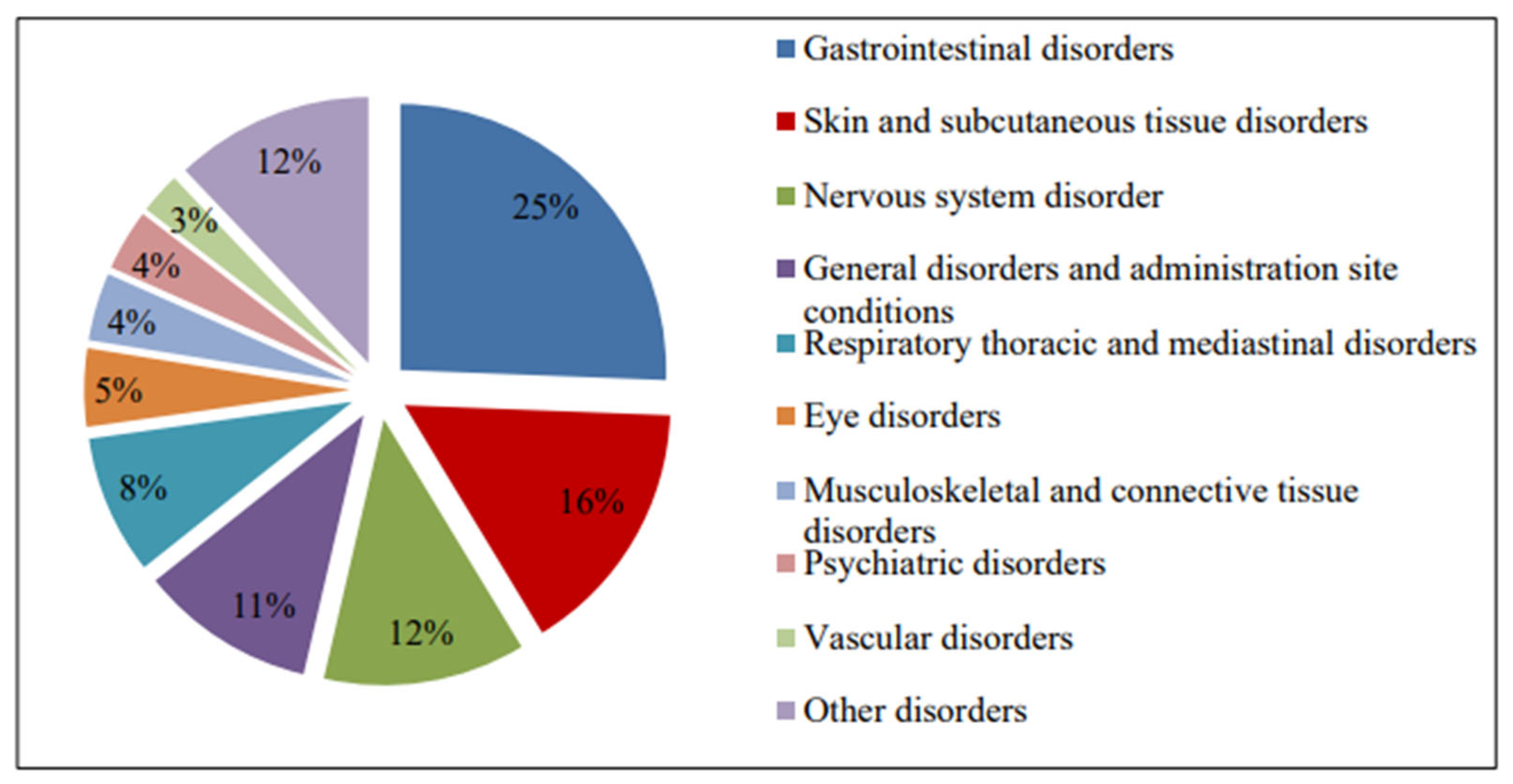

3.2. The Most Common Reported Adverse Drug Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The World Health Organization. The Importance of Pharmacovigilance: Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products. 2002. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-42493 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Drug Monitoring: The Role of National Centres; Technical Report Series No. 498; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute for Medicines and Medical Devices CInMED. Available online: https://www.cinmed.me (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Sipetic, T.; Rajkovic, D.; Bogavac Stanojevic, N.; Marinkovic, V.; Mestrovic, A.; Rouse, M.J. SMART Pharmacists Serving the New Needs of the Post-COVID Patients, Leaving No-One Behind. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apikoglu, S.; Selcuk, A.; Ozcan, V.; Balta, E.; Turker, M.; Albayrak, O.D.; Meštrović, A.; Rouse, M.; Uney, A. The first nationwide implementation of pharmaceutical care practices through a continuing professional development approach for community pharmacists. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Definition of Continuing Professional Development. Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/continuing-professional-development/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Guidance on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for the Profession of Pharmacy. Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPDGuidance%20ProfessionPharmacyJan2015.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Rouse, M.J.; Meštrović, A. Learn Today–Apply Tomorrow: The SMART Pharmacist Program. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmaceutical Chamber of Montenegro. Available online: https://fkcg.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Zakon-o-apotekarskoj-djelatnosti.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Marupuru, S.; Roether, A.; Guimond, A.J.; Stanley, C.; Pesqueira, T.; Axon, D.R. A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes from Pharmacist Provided Medication Therapy Management (MTM) among Patients with Diabetes, Hypertension, or Dyslipidemia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tharpe, N. Adverse Drug Reactions in Women’s Health Care. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2011, 56, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicines and Medical Devices Agency of Serbia (ALIMS). Available online: https://www.alims.gov.rs/english/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices of Croatia (HALMED). Available online: https://www.halmed.hr/en/Farmakovigilancija/Izvjesca-o-nuspojavama/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Bouvy, J.C.; De Bruin, M.L.; Koopmanschap, M.A. Epidemiology of Adverse Drug Reactions in Europe: A Review of Recent Observational Studies. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarou, J.; Pomeranz, B.H.; Corey, P.N. Incidence of Adverse Drug Reactions in Hospitalized Patients: A Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. JAMA. 1998, 279, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Grootheest, K.; Van Puijenbroek, E.B.; De Jong–van den Berg, W.T.L. Contribution of pharmacists to the reporting of adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2002, 11, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.F.; Mottram, D.R.; Rowe, P.H.; Pirmohamed, M. Attitudes and knowledge of hospital pharmacists to adverse drug reaction reporting. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 51, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Grootheest, K.; Olsson, S.; Couper, M.; de Jong-van den Berg, L. Pharmacists’ role in reporting adverse drug reactions in an international perspective. Pharmacoepidemol. Drug Safety 2004, 13, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, R.; Moretti, U.; D’Incau, P.; Conforti, A.; Magro, L.; Lora, R.; Velo, G. Effect of Pharmacist Involvement on Patient Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions: First Italian Study. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, M.A.; Neoh, C.F.; Zin, R.M.; Elrggal, M.E.; Cheema, E. Pharmacovigilance: Pharmacists’ perspective on spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2017, 6, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glamočlija, U.; Tubić, B.; Kondža, M.; Zolak, A.; Grubiša, N. Adverse drug reaction reporting and development of pharmacovigilance systems in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro: A retrospective pharmacoepidemiological study. Croat Med. J. 2018, 59, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices of Montenegro. Report of the Drug Side Effects for 2016; Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2017. (In Montenegrin) [Google Scholar]

- Paut Kusturica, M.; Tomas, A.; Rašković, A.; Gigov, S.; Crnobrnja, V.; Jevtić, M.; Stilinović, N. Community pharmacists’ challenges regarding adverse drug reaction reporting: A cross-sectional study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2022, 38, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snežana, M.; Maja, S.; Nemanja, T.; Majda, Š.-Z.; Željka, B.; Milorad, D. Pharmacovigilance as an imperative of modern medicine—Experience from Montenegro. Vojnosanit. Pregled. 2016, 74, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkhonmath, N.; Olson, P.S.; Puttarak, P.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Sawangjit, R. Systematic review and meta-analysis on effectiveness of strategies for enhancing adverse drug reaction reporting. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2025, 65, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AGE GROUP | NUMBER OF REPORTS |

|---|---|

| 0–27 days | 0 (0%) |

| 28 days–23 months | 2 (0.7%) |

| 2–11 years | 7 (2.3%) |

| 12–17 years | 0 (0%) |

| 18–44 years | 79 (26.1%) |

| 45–64 years | 134 (44.4%) |

| 65–74 years | 50 (16.5%) |

| ≥75 years old | 30 (9.9%) |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF REPORTS | 302 (100%) |

| ATC | ATC Classification Core Group | Number of Reported Medicines |

|---|---|---|

| A | Alimentary tract and metabolism (medicines that act on diseases of the digestive system and metabolism) | 40 |

| B | Blood and hematopoietic organs (medicines used to treat blood and hematopoietic organs) | 22 |

| C | Cardiovascular system (medicines that act on the cardiovascular system) | 84 |

| D | Skin and subcutaneous tissue (medicines used to treat diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue) | 7 |

| G | Genitourinary system and sex hormones (medicines for the treatment of the genitourinary system and sex hormones) | 13 |

| H | Hormonal preparations for systemic administration, excluding sex hormones and insulin | 3 |

| J | Anti-infective drugs for systemic use | 45 |

| L | Antineoplastics and immunomodulators | 9 |

| M | Musculoskeletal system (medicines for diseases of the musculoskeletal system) | 33 |

| N | Nervous system (medicines that act on the nervous system) | 30 |

| P | Antiparasitic products, insecticides and insect repellents (medicines for the treatment of infections caused by parasites) | 4 |

| R | Respiratory system (medicines to treat diseases of the respiratory system) | 18 |

| W | Sensory organs (medicines that affect the eye and ear) | 6 |

| V | Miscellaneous | 0 |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF MEDICINES | 314 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mugoša, S.; Meštrović, A.; Vukićević, V.; Žugić, M.; Rouse, M.J. SMART Pharmacist—The Impact of Education on Improving Pharmacists’ Participation in Monitoring the Safety of Medicine Use in Montenegro. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13020057

Mugoša S, Meštrović A, Vukićević V, Žugić M, Rouse MJ. SMART Pharmacist—The Impact of Education on Improving Pharmacists’ Participation in Monitoring the Safety of Medicine Use in Montenegro. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(2):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13020057

Chicago/Turabian StyleMugoša, Snežana, Arijana Meštrović, Veselinka Vukićević, Milanka Žugić, and Michael J. Rouse. 2025. "SMART Pharmacist—The Impact of Education on Improving Pharmacists’ Participation in Monitoring the Safety of Medicine Use in Montenegro" Pharmacy 13, no. 2: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13020057

APA StyleMugoša, S., Meštrović, A., Vukićević, V., Žugić, M., & Rouse, M. J. (2025). SMART Pharmacist—The Impact of Education on Improving Pharmacists’ Participation in Monitoring the Safety of Medicine Use in Montenegro. Pharmacy, 13(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13020057