A Review of Studies on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Community Pharmacies in States with Restrictive Pharmacist Prescription Authority in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. HIV Epidemic and Health Disparities

1.2. Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Medications

1.3. PrEP Uptake and Challenges

1.4. Pharmacist’s Role Expansion to Increase PrEP Uptake in High-Risk Populations

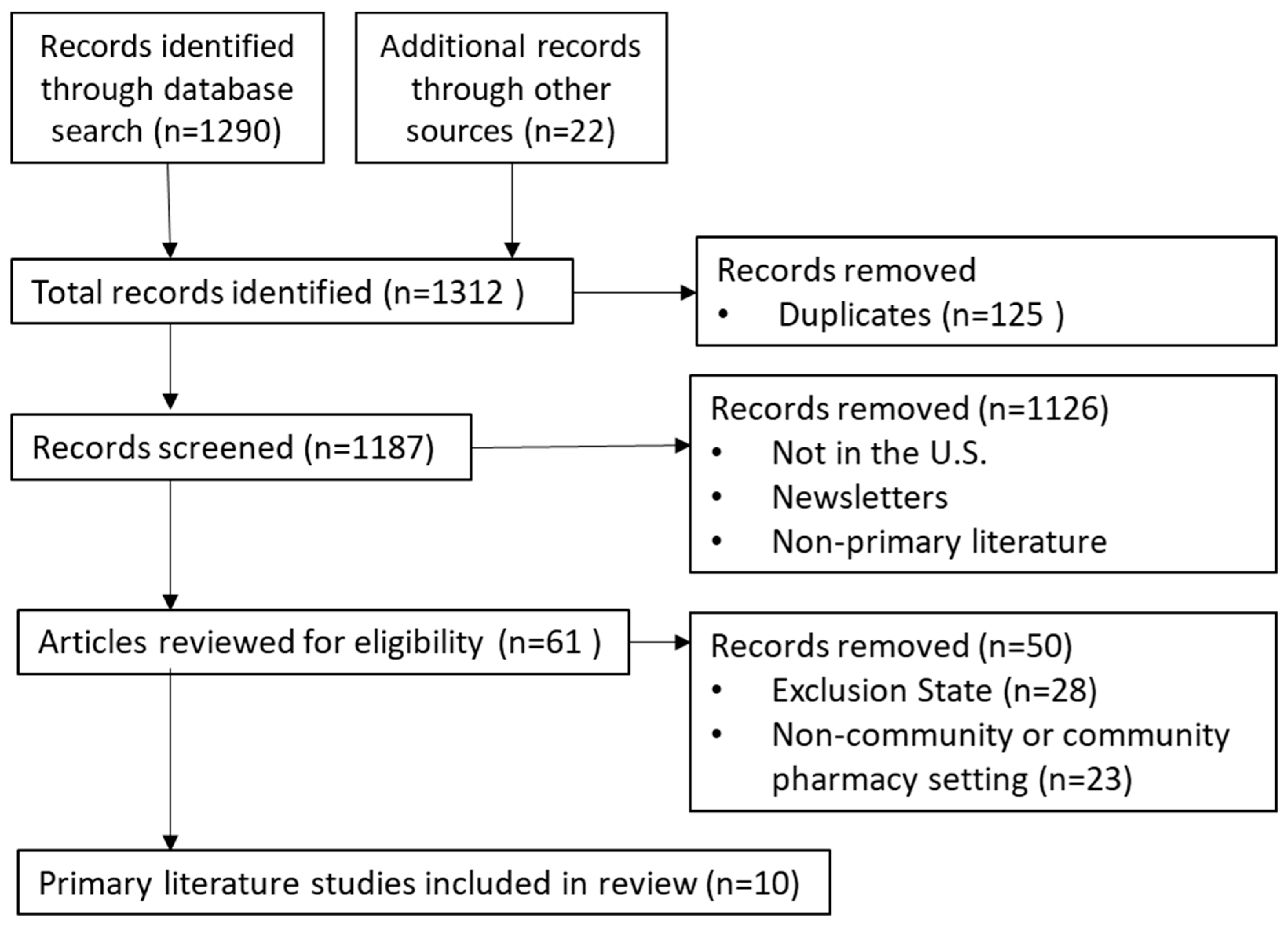

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Surveys and Interviews

3.2. Intervention Reports

3.3. Clinical Trial in Progress

4. Discussion

4.1. How Does a Pharmacist Provide HIV and PrEP Services in the Community Setting in Prescriptive Authority Restricted States?

4.2. How Do Important Stakeholders Feel about Pharmacists Providing HIV and PrEP Services in the Community Setting in Prescriptive Authority Restricted States?

4.3. What Gaps Are Yet to Be Filled to Implement HIV and PrEP Services in the Community Pharmacy Setting in Prescriptive Authority Restricted States?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNAIDS 2023 Report. UNAIDS—Global Report 2023. Available online: https://thepath.unaids.org/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention AtlasPlus—Map. Explore CDC’s Atlas Plus HIV+Hepatitis+STD+TB+Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/nchhstpatlas/maps.html (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses, Deaths, and Prevalence of HIV in the United States and 6 Territories and Freely Associated States. 2022. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/156509 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2021 Update: A Clinical Practice Guideline. CDC. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- FDA. FDA Approves First Injectable Treatment for HIV Pre-Exposure Prevention. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- CDC. Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US (EHE). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ehe/index.html (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- CDC. HIV in the U.S. by the Numbers—2021. NCHHSTP Newsroom. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp-newsroom/factsheets/hiv-in-us-by-the-numbers-2021.html (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- PrEP4All. Toward PrEP Access for All: An Analysis of Policies, Approaches, and Strategies in the Southern United States. Available online: https://prep4all.org/publication/sac-report/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Sophus, A.I.; Mitchell, J.W. A Review of Approaches Used to Increase Awareness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 1749–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenbrok, L.A.; Tang, S.; Gabriel, N.; Guo, J.; Sharareh, N.; Patel, N.; Dickson, S.; Hernandez, I. Access to Community Pharmacies: A Nationwide Geographic Information Systems Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1816–1822.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogue, M. CEO Blog. Pharmacists Expand Access to PrEP in 17 States. American Pharmacists Association. Available online: https://www.pharmacist.com/CEO-Blog/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Home|ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Ahmed, K.K.M.; Al Dhubaib, B.E. Zotero: A Bibliographic Assistant to Researcher. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C.M.; Endres, K.; Derrick, C.; Cooper, A.; Fabel, P.; Okeke, N.L.; Ahuja, D.; Corneli, A.; McKellar, M.S. A Survey of South Carolina Pharmacists’ Readiness to Prescribe Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. JAACP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2023, 6, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, N.D.; Josma, D.; Morris, J.; Hopkins, R.; Young, H.N. Pharmacy-Based Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Support among Pharmacists and Men Who Have Sex with Men. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, R.; Josma, D.; Morris, J.; Klepser, D.G.; Young, H.N.; Crawford, N.D. Support and Perceived Barriers to Implementing Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Screening and Dispensing in Pharmacies: Examining Concordance between Pharmacy Technicians and Pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaeer, K.M.; Sherman, E.M.; Shafiq, S.; Hardigan, P. Exploratory Survey of Florida Pharmacists’ Experience, Knowledge, and Perception of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2014, 54, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoth, A.B.; Shafer, C.; Dillon, D.B.; Mayer, R.; Walton, G.; Ohl, M.E. Iowa TelePrEP: A Public-Health-Partnered Telehealth Model for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Preexposure Prophylaxis Delivery in a Rural State. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 46, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasco, E.E.; Shafer, C.; Dillon, D.M.; Owens, S.; Ohl, M.E.; Hoth, A.B. Bringing Iowa TelePrEP to Scale: A Qualitative Evaluation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, S108–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosropour, C.M.; Backus, K.V.; Means, A.R.; Beauchamps, L.; Johnson, K.; Golden, M.R.; Mena, L. A Pharmacist-Led, Same-Day, HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiation Program to Increase PrEP Uptake and Decrease Time to PrEP Initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2020, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, T.; Layson-Wolf, C.; Seung, H.; Banjo, O.; Tran, D. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Program on Knowledge of College Students about Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, S30–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.J.K. FINISHING HIV: An Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) Model for Latinx Integrating One-Stop-Shop Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Services, a Social Network Support Program and a National Pharmacy Chain; Clinical Trial Registration NCT06406049. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06406049 (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Crawford, N. Advancing Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Access in Pharmacies to Improve PrEP Uptake in Disadvantaged Areas; Clinical Trial Registration NCT04393935. 2023. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04393935 (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- NASTAD. Pharmacists’ Authority to Initiate PrEP and PEP and Engage in Collaborative Practice Agreements. Available online: https://nastad.org/resources/pharmacists-authority-engage-collaborative-practice-agreements-and-initiate-prep-pep-and (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Cocohoba, J.; Tweedie, L.; Frank, M.; McElya, B.; Witt, E. Legislation Expanding Pharmacist Scope of Practice to Furnish Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: A Content Analysis. JACCP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 7, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.N.; Martin, M.T.; Tilton, J.J.; Touchette, D.R. Medication Therapy Management Services: Definitions and Outcomes. Drugs 2009, 69, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HIV Testing Sites & Care Services Locator. Available online: https://locator.hiv.gov/map (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- PrEP Locator: A National Database for US PrEP Providers. US PrEP Provider Directory. Available online: https://preplocator.org/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Gregory, P.A.; Austin, Z. How Do Patients Develop Trust in Community Pharmacists? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanczyk, D.M.; Merlo, J.R.; Bradley, B.; Flannery, A.H.; Gibson, C.M.; McBane, S.; Murphy, J.A.; Noble, J.M.; Noble, M.B.; Patton, H.M.; et al. 2023 Update to the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Pharmacotherapy Didactic Curriculum Toolkit. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 7, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Pharmacists Association. Pharmacy-Based HIV Prevention Services. Available online: https://www.pharmacist.com/Education/Certificate-Training-Programs/Pharmacy-Based-HIV-Prevention-Services (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Saberi, P.; Su, H.; Mendiola, J.; Gruta, C.; Lutes, E.R.; Dong, B.; Bositis, C.; Chu, C. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Champion Preceptorship Training for Pharmacists and Nurses in the United States. JACCP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 7, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekhuis, J.M.; Scarsi, K.K.; Sayles, H.R.; Klepser, D.G.; Havens, J.P.; Swindells, S.; Bares, S.H. Midwest Pharmacists’ Familiarity, Experience, and Willingness to Provide Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | State/Setting | Methods | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns CM et al. (2023) [14] | South Carolina Retail, hospital, independent, community, specialty, academia | 43-question online survey through a pharmacist listserv | More than half of pharmacists (n = 129) responded ready and willing to prescribe PrEP | Low response rate; only pharmacists in the university’s listserv were invited |

| Crawford ND et al. (2020) [15] | Georgia Community pharmacies in zip codes with high HIV incidence | Semi-structured interviews of pharmacists and MSM clients | Participants (n = 14) reported in supportive of HIV, STI, and PrEP screenings | Small sample size; limited to urban setting |

| Hopkins R et al. (2021) [16] | Georgia Community pharmacies in zip codes with high HIV incidence | Semi-structured interviews of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians | Community pharmacists (n = 7) and pharmacy technicians (n = 6) were supportive of implementation of HIV and PrEP screening | Small sample size; perception may differ among other stakeholders |

| Shaeer KM et al. (2014) [17] | Florida Community pharmacies | In-person and online survey | Pharmacists (n = 225) reported limited understanding of PrEP and more education was needed | Perception may have changed after the study period 10 years ago |

| Author (Year) | State/Setting | Methods | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holt AB (2019) [18] Chasco EE et al. (2021) [19] | Iowa Statewide public health departments and University of Iowa collaboration | The pharmacists provided counseling and prescribed PrEP through a collaborative practice model | 12 public health partners referred 708 individuals over 18 month period; 258 individuals received TelePrEP service; and 167 individuals initiated PrEP | Intentional sampling may lead to bias; did not measure adherence to PrEP |

| Khosropour CM et al. (2020) [20] | Mississippi An academic affiliated HIV/STD testing center located next to the state health department STD clinic | The clinical pharmacist received patient referrals from a STD clinic, collected medical history, prescribed PrEP through collaborative practice agreements, and provided a follow up appointment | 69 patients were referred to clinical pharmacy service over a 7-month period; 80% received a PrEP prescription on the same day; 77% filled the PrEP prescription; and 43% of those who filled the prescription attended a follow up appointment | Small sample size; lack of control group; not in community pharmacy setting |

| Taliaferro T et al. (2021) [21] | Washington, DC College campus | The pharmacist provided a 30-minute education to college students about HIV prevention and PrEP | Participants (n = 102) reported an increase in perception of HIV and PrEP knowledge after the education compared to baseline | Lack of control group; self-reported subjective measure of knowledge |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Guinn, D.; Ramisetty, X.R.; Giordano, T.P.; Poon, I.O. A Review of Studies on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Community Pharmacies in States with Restrictive Pharmacist Prescription Authority in the United States. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12050144

Wang H, Guinn D, Ramisetty XR, Giordano TP, Poon IO. A Review of Studies on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Community Pharmacies in States with Restrictive Pharmacist Prescription Authority in the United States. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(5):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12050144

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hongmei, Dominique Guinn, Xavier Roshitha Ramisetty, Thomas P. Giordano, and Ivy O. Poon. 2024. "A Review of Studies on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Community Pharmacies in States with Restrictive Pharmacist Prescription Authority in the United States" Pharmacy 12, no. 5: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12050144

APA StyleWang, H., Guinn, D., Ramisetty, X. R., Giordano, T. P., & Poon, I. O. (2024). A Review of Studies on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Community Pharmacies in States with Restrictive Pharmacist Prescription Authority in the United States. Pharmacy, 12(5), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12050144