Mental Health Evaluation in Community Pharmacies—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. GAD-7 and PHQ-9 Global Scores

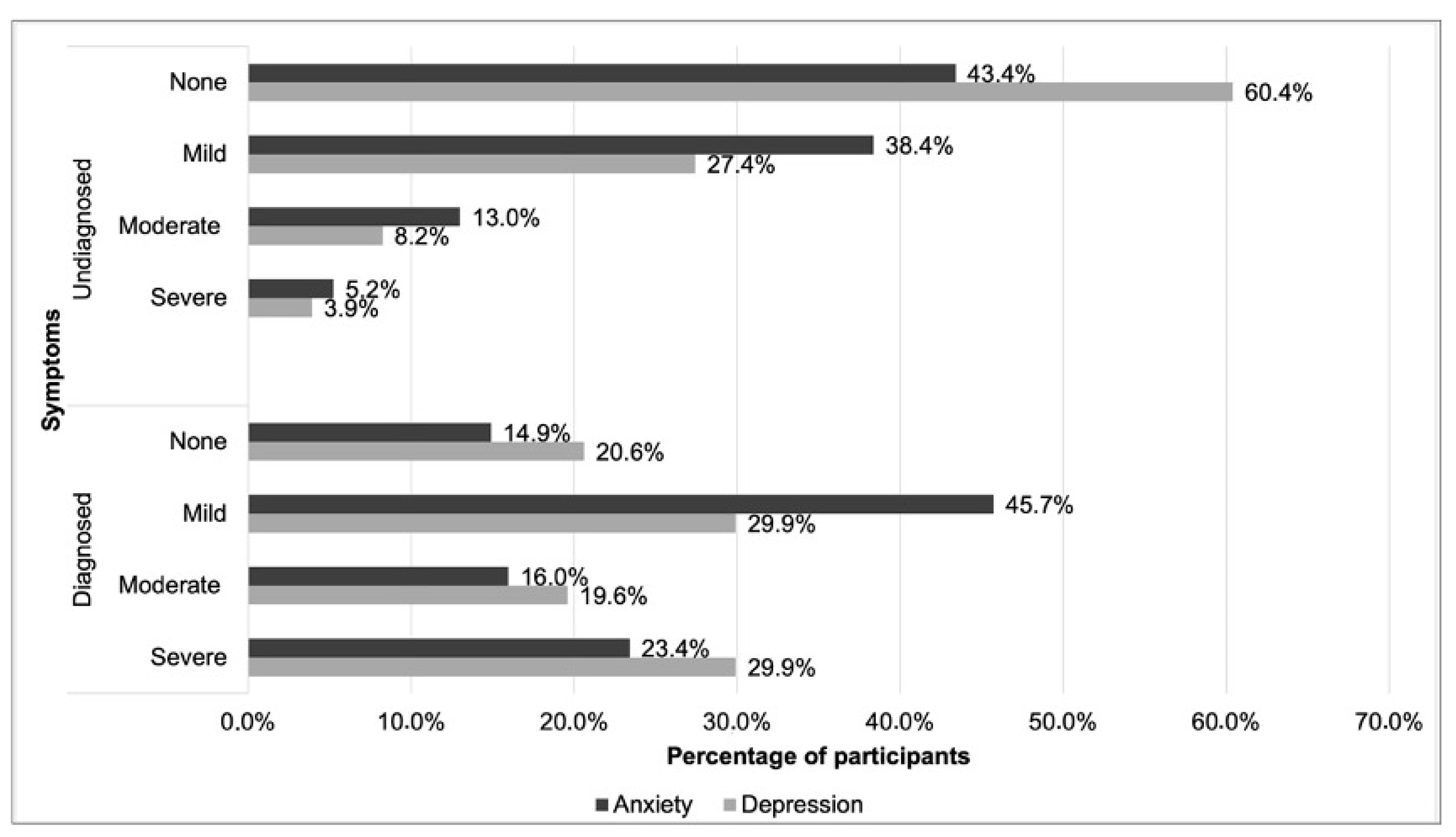

3.2. GAD-7 and PHQ-9 Scores in Undiagnosed and Diagnosed Participants with Anxiety or Depression

3.3. Analysis of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms’ Frequency

4. Discussion

4.1. Screening for Anxiety and Depression (Participants without a Diagnosis of Anxiety or Depression)

4.2. Assessment of Anxiety and Depression (Participants Diagnosed with Anxiety and Depression)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems. OECD Health Policy Studies. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/a-new-benchmark-for-mental-health-systems_4ed890f6-en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- European Commission. State of Health in the EU. Portugal. Country Health Profile 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/069af7b1-en.pdf?expires=1714043539&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=507539C29AF912EC36CFAF146555BD1C (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study; IHME: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2018_health_glance_eur-2018-en (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2022_507433b0-en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2021; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Relatório Final: SM-COVID19—Saúde Mental em Tempos de Pandemia. Available online: http://repositorio.insa.pt/handle/10400.18/7245 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Better Mental Health Together. Position Statement. 2021. Available online: https://www.europsy.net/app/uploads/2021/05/Joint-statement-Mental-health-18-May_FINAL_endorsed.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Eder, J.; Dom, G.; Gorwood, P.; Kärkkäinen, H.; Decraene, A.; Kumpf, U.; Beezhold, J.; Samochowiec, J.; Kurimay, T.; Gaebel, W.; et al. Improving mental health care in depression: A call for action. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health Care: A Handbook for Pharmacists. 2022. Available online: https://www.fip.org/file/5212 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Moore, C.H.; Powell, B.D.; Kyle, J.A. The Role of the community pharmacist in mental health. US Pharm. 2018, 43, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, T.V.; Viveiros, V.; Chai, M.V.; Vicente, F.L.; Jesus, G.; Carnot, M.J.; Gordo, A.C.; Ferreira, P.L. Reliability and validity of the Portuguese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Sousa, M.; Salgado, J. Brief assessment of depression: Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Psychol. Pract. Res. J. 2019, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonde, L.; Khunti, K.; Harris, S.B.; Meizinger, C.; Skolnik, N.S. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PORDATA. População Residente Segundo os Censos: Total e Por Sexo. 2021. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/db/municipios/ambiente+de+consulta/tabela (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- PORDATA. Censos de Portugal em 2021: Resultados por Tema e por Concelho—Famílias. 2021. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/censos/resultados/familias-alentejo-592 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Caldas De Almeida, M.; Xavier, M.; Cardoso, G.; Pereira, M.G.; Gusmão, R.; Corrêa, B.; Gago, J.; Talina, M.; Silva, J. Estudo Epidemiológico Nacional de Saúde Mental—1o Relatório; Faculdade de Ciências Médicas Universidade Nova de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ek, S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okui, T. An analysis of health inequalities depending on educational level using nationally representative survey data in Japan, 2019. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, S.; Goggins, K.; Couey, C.; Yeh, V.M.; Donato, K.M.; Schnelle, J.F.; Wallston, K.A.; Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study. Disparities in Research Participation by Level of Health Literacy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, C.H.; Nefs, G.; Pop, V.J.; Pouwer, F. Screening for and subsequent participation in a trial for depression and anxiety in people with type 2 diabetes treated in primary care: Who do we reach? Prim. Care Diabetes 2017, 11, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Navarro, R.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Moriana, J.A.; Medrano, L.A.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, P.; Agüero-Gento, L.; Rodríguez-Enríquez, M.; Pizà, M.R.; Ramírez-Manent, J.I. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder in Spanish primary care centers with the GAD-7. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujanpää, T.; Ylisaukko-Oja, T.; Jokelainen, J.; Hirsikangas, S.; Kanste, O.; Kyngäs, H.; Timonen, M. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among Finnish primary care high utilizers and validation of Finnish translation of GAD-7 and GAD-2 screening tools. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2014, 32, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, M.M.; Bieling, P.J.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Swinson, R.P. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, A.L.; Evans, K.R.; Sills, T.L.; Kalali, A.H. Symptoms of anxiety in depression: Assessment of item performance of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale in patients with depression. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E. Tradução, Adaptação Cultural e Avaliação das Propriedades Psicométricas da Escala de Ansiedade de Hamilton Numa Amostra de Pessoas Adultas com Doença Mental da População Portuguesa. Escola Superior de Enfermagem. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/39338 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Shear, M.K.; Vander Bilt, J.; Rucci, P.; Endicott, J.; Lydiard, B.; Otto, M.W.; Pollack, M.H.; Chandler, L.; Williams, J.; Ali, A.; et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depress. Anxiety 2001, 13, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D. UpToDate. 2023 Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Adults: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Course, Assessment and Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/generalized-anxiety-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis?search=tools%20for%20generalized%20anxiety%20evaluation&source=search_result&selectedTitle=6~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=6#H430164280 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Chyczij, F.F.; Ramos, C.; Santos, A.; Jesus, L.; Alexandre, J. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in patients of a family health unit in northern Portugal. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2020, 5, e19094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.; Carlbring, P.; Heedman Åsa Paxling, B.; Andersson, G. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: Point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ 2013, 1, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. The Prevalence and correlates of probable major depressive Disorder and probable generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a nationally representative survey in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl-Pehe, A.; Selinski, S.; Bächle, C.; Castillo, K.; Lange, K.; Holl, R.W.; Rosenbauer, J. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and associated factors in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes: Cross-sectional results of a Germany-wide population-based study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 184, 109197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, T.M.; Kowalski, A.; Lahrman, R. Assessing a pharmacist-provided mental health screening service in a rural community to address anxiety and depression. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, H.; Smith, P.; Berete, F.; Demarest, S.; Hermans, L.; Braekman, E.; Charafeddine, R.; Drieskens, S.; De Ridder, K.; Gisle, L. Anxiety and depression in Belgium during the first 15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rus Makovec, M.; Vintar, N.; Makovec, S. Self-reported depression, anxiety and evaluation of own pain in clinical sample of patients with different location of chronic pain. Slov. J. Public Health 2015, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büyükşireci, D.E.; Türk, A.Ç.; Erden, E.; Erden, E. Evaluation of pain, disease activity, anxiety, depression and neuropathic pain levels after COVID-19 infection in fibromyalgia patients. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Nichols, R.; Veach, S.; Alhersh, E.; Witry, M. Evaluation of an enhanced depression and anxiety screening with targeted pharmacist intervention. J. Am. Pharma Assoc. 2024, 64, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M.; Haas, M.; Larew, J.; DeJongh, B. Impact of a mental health clinical pharmacist on a primary care mental health integration team. Ment. Health Clin. 2017, 7, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, E.; McLelland, R.; Rushworth, G.F.; Stewart, D.; Gibson-Smith, K.; MacLure, A.; Cunningham, S.; MacLure, K. An evaluation of mental health clinical pharmacist independent prescribers within general practice in remote and rural Scotland. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.; Kamo, N. Utilizing clinical pharmacists to improve delivery of evidence-based care for depression and anxiety in primary care. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 2016, 5, u211816.w4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handyside, L.; Warren, R.; Devine, S.; Drovandi, A. Health needs assessment in a regional community pharmacy using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, V.A.; Stencel, N.L.; Ives, R.C.; Ward, K.M.; Fluent, T.; Choe, H.M.; Bostwick, J.R. A pilot evaluating clinical pharmacy services in an ambulatory psychiatry setting. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2018, 48, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mishriky, J.; Stupans, I.; Chan, V. Expanding the role of Australian pharmacists in community pharmacies in chronic pain management—A narrative review. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, C.; Winkler, H. Impact of a clinical pharmacist-managed clinic in primary care mental health integration at a Veterans Affairs health system. Ment. Health Clin. 2018, 8, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C.; Winkler, H.; Moore, T.A. Outcomes of mental health pharmacist-managed electronic consults at a Veterans Affairs health care system. Ment. Health Clin. 2017, 7, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 148 | 25.1 |

| Female | 441 | 74.9 |

| NA | 2 | - |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | 114 | 21.1 |

| 35–64 | 306 | 56.7 |

| ≥65 | 120 | 22.2 |

| NA | 51 | - |

| Education | ||

| No school | 5 | 0.9 |

| 1st cycle (4 years) | 89 | 15.3 |

| 2nd cycle (6 years) | 30 | 5.2 |

| 3rd cycle (9 years) | 72 | 12.4 |

| Secondary (12 years) | 193 | 33.2 |

| Higher | 193 | 33.2 |

| NA | 9 | - |

| Professional status | ||

| Employee * | 401 | 68.1 |

| Retired | 132 | 22.4 |

| Unemployed | 56 | 9.5 |

| NA | 2 | - |

| Live alone | ||

| Yes | 82 | 14.1 |

| No | 501 | 85.9 |

| NA | 8 | - |

| Pets | ||

| Yes | 340 | 59.1 |

| No | 235 | 40.9 |

| NA | 16 | - |

| GAD-7 (Qualitative Scores) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | No Symptoms N (%) | Mild N (%) | Moderate N (%) | Severe N (%) | Total N (%) | Mean (CI 95%) Median | Significance |

| Sex | U = 40,042.000; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 86 (58.9) | 42 (28.8) | 13 (8.9) | 5 (3.4) | 146 (100) | 0.57 (0.44; 0.70) 0.00 | |

| Female | 133 (31.4) | 184 (43.5) | 64 (15.1) | 42 (9.9) | 423 (100) | 1.04 (0.95; 1.12) 1.00 | |

| Age | KW = 1.415; p = 0.493 | ||||||

| 18–34 | 45 (39.5) | 50 (43.9) | 13 (11.4) | 6 (5.3) | 114 (100) | 0.82 (0.67; 0.98) 1.00 | |

| 35–64 | 107 (36.1) | 120 (40.5) | 41 (13.9) | 28 (9.5) | 296 (100) | 0.97 (0.86; 1.07) 1.00 | |

| 65–83 | 48 (42.5) | 35 (31.0) | 18 (15.9) | 12 (10.6) | 113 (100) | 0.95 (0.76; 1.13) 1.00 | |

| Education level | KW = 4.443; p = 0.217 | ||||||

| <Middle school | 29 (33.3) | 32 (36.8) | 13 (14.9) | 13 (14.9) | 87 (100) | 1.11 (0.89; 1.34) 1.00 | |

| Middle school | 41 (41.8) | 30 (30.6) | 15 (15.3) | 12 (12.2) | 98 (100) | 0.98 (0.77; 1.19) 1.00 | |

| Secondary | 78 (41.3) | 69 (36.5) | 29 (15.3) | 13 (6.9) | 189 (100) | 0.88 (0.75; 1.01) 1.00 | |

| Higher | 72 (38.3) | 89 (47.3) | 18 (9.6) | 9 (4.8) | 188 (100) | 0.81 (0.69; 0.92) 1.00 | |

| Professional status | KW = 0.769; p = 0.681 | ||||||

| Active/Medical leave | 153 (39.1) | 162 (41.4) | 44 (11.3) | 32 (8.2) | 391 (100) | 0.88 (0.79; 0.97) 1.00 | |

| Retired | 50 (40.0) | 42 (33.6) | 21 (16.8) | 12 (9.6) | 125 (100) | 0.96 (0.79; 1.13) 1.00 | |

| Unemployed | 18 (34.0) | 22 (41.5) | 11 (20.8) | 2 (3.8) | 53 (100) | 0.94 (0.71; 1.18) 1.00 | |

| With whom do you live? | U = 17,315.500; p = 0.190 | ||||||

| Live alone | 27 (34.6) | 29 (37.2) | 12 (15.4) | 10 (12.8) | 78 (100) | 1.06 (0.84; 1.29) 1.00 | |

| Live together | 190 (39.1) | 195 (40.1) | 65 (13.4) | 36 (7.4) | 486 (100) | 0.89 (0.81; 0.97) 1.00 | |

| Pet owners | U = 35,711.500; p = 0.347 | ||||||

| Yes | 126 (38.0) | 130 (39.2) | 45 (13.6) | 31 (9.3) | 332 (100) | 0.94 (0.84; 1.04) 1.00 | |

| No | 90 (40.0) | 92 (40.9) | 30 (13.3) | 13 (5.8) | 225 (100) | 0.85 (0.74; 0.96) 1.00 | |

| PHQ-9 (Qualitative Scores) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | No Symptoms N (%) | Mild N (%) | Moderate N (%) | Severe N (%) | Total N (%) | Mean (CI 95%) Median | Significance |

| Sex | U = 39,394.500; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 105 (70.9) | 25 (16.9) | 12 (8.1) | 6 (4.1) | 148 (100) | 0.45 (0.32; 0.58) 0.00 | |

| Female | 206 (47.7) | 137 (31.7) | 47 (10.9) | 42 (9.7) | 432 (100) | 0.83 (0.73; 0.92) 1.00 | |

| Age | KW = 0.0722; p > 0.05 | ||||||

| 18–34 | 60 (53.1) | 34 (30.1) | 11 (9.7) | 8 (7.1) | 113 (100) | 0.71 (0.54; 0.88) 0.00 | |

| 35–64 | 158 (52.1) | 91 (30.0) | 33 (10.9) | 21 (6.9) | 303 (100) | 0.73 (0.62; 0.83) 0.00 | |

| 65–83 | 61 (52.6) | 25 (21.6) | 13 (11.2) | 17 (14.7) | 116 (100) | 0.88 (0.68; 1.08) 0.00 | |

| Education level | KW = 13.031 p < 0.005 | ||||||

| <Middle school | 38 (42.2) | 26 (28.9) | 12 (13.3) | 14 (15.6) | 90 (100) | 1.02 (0.79; 1.25) 1.00 | |

| Middle school | 51 (50.5) | 24 (23.8) | 14 (13.9) | 12 (11.9) | 101 (100) | 0.87 (0.66; 1.08) 0.00 | |

| Secondary | 107 (56.3) | 53 (27.9) | 15 (7.9) | 15 (7.9) | 190 (100) | 0.67 (0.54; 0.81) 0.00 | |

| Higher | 113 (58.9) | 56 (29.2) | 16 (8.3) | 7 (3.6) | 192 (100) | 0.57 (0.45; 0.68) 0.00 | |

| Professional status | KW = 4.950 p = 0.084 | ||||||

| Active/Medical leave | 221 (55.8) | 116 (29.3) | 33 (8.3) | 26 (6.6) | 396 (100) | 0.66(0.57; 0.74) 0.00 | |

| Retired | 66 (51.2) | 35 (27.1) | 14 (10.9) | 14 (10.9) | 129 (100) | 0.81(0.64; 0.99) 0.00 | |

| Unemployed | 26 (47.3) | 11 (20.0) | 11 (20.0) | 7 (12.7) | 55 (100) | 0.98(0.69; 1.28) 1.00 | |

| With whom do you live? | U = 16,227.500 p = 0.007 | ||||||

| Live alone | 35 (44.3) | 18 (22.8) | 13 (16.5) | 13 (16.5) | 79 (100) | 1.05 (0.80; 1.3) 1.00 | |

| Live together | 273 (55.2) | 142 (28.7) | 46 (9.3) | 34 (6.9) | 495 (100) | 0.68 (0.60; 0.76) 0.00 | |

| Pet owners | U = 36,612.000; p = 0.219 | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (52.1) | 94 (28.1) | 34 (10.2) | 32 (9.6) | 334 (100) | 0.77 (0.67; 0.88) 0.00 | |

| No | 131 (56.5) | 63 (27.2) | 24 (10.3) | 14 (6.0) | 232 (100) | 0.66 (0.54; 0.77) 0.00 | |

| GAD-7 (Qualitative Scores) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No Symptoms N (%) | Mild N (%) | Moderate N (%) | Severe N (%) | Total N (%) | Mean (CI 95%) Median | Significance |

| Taking medicine | U = 30,901.000; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 121 (34.1) | 136 (38.3) | 59 (16.6) | 39 (11.0) | 355 (100) | 1.05 (0.94; 1.15) 1.00 | |

| No | 100 (46.3) | 90 (41.7) | 18 (8.3) | 8 (3.7) | 216 (100) | 0.69 (0.59; 0.80) 1.00 | |

| Pain medicine | U = 17,186.000; p = 0.005 | ||||||

| Yes | 24 (27.9) | 34 (39.5) | 18 (20.9) | 10 (11.6) | 86 (100) | 1.16 (0.96; 1.37) 1.00 | |

| No | 197 (40.6) | 192 (39.6) | 59 (12.2) | 37 (7.6) | 485 (100) | 0.87 (0.79; 0.95) 1.00 | |

| Insomnia medicine | U = 8266.000; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (10.9) | 22 (34.4) | 17 (26.6) | 18 (28.1) | 64 (100) | 1.72 (1.47; 1.97) 2.00 | |

| No | 214 (42.2) | 204 (40.2) | 60 (11.8) | 29 (5.7) | 507 (100) | 0.81 (0.74; 0.89) 1.00 | |

| Anxiety medicine | U = 14,019.500; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (14.9) | 43 (45.7) | 15 (16.0) | 22 (23.4) | 94 (100) | 1.48 (1.27; 1.69) 1.00 | |

| No | 207 (43.4) | 183 (38.4) | 62 (13.0) | 25 (5.2) | 477 (100) | 0.80 (0.72; 0.88) 1.00 | |

| Depression medicine | U = 11,474.000; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (10.9) | 36 (39.1) | 24 (26.1) | 22 (23.9) | 92 (100) | 1.63 (1.43; 1.83) 1.50 | |

| No | 211 (44.1) | 190 (39.7) | 53 (11.1) | 25 (5.2) | 479 (100) | 0.77 (0.70; 0.85) 1.00 | |

| PHQ-9 (Qualitative Scores) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No Symptoms N (%) | Mild N (%) | Moderate N (%) | Severe N (%) | Total N (%) | Mean (CI 95%) Median | Significance |

| Taking medicine | U = 30,976.500; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (47.7) | 100 (27.4) | 48 (13.2) | 43 (11.8) | 365 (100) | 0.89 (0.78; 1.00) 1.00 | |

| No | 139 (64.1) | 62 (28.6) | 11 (5.1) | 5 (2.3) | 217 (100) | 0.46 (0.36; 0.55) 0.00 | |

| Pain medicine | U = 138,898.000; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 35 (39.3) | 24 (27.0) | 18 (20.2) | 12 (13.5) | 89 (100) | 1.08 (0.85; 1.30) 1.00 | |

| No | 278 (56.4) | 138 (28.0) | 41 (8.3) | 36 (7.3) | 493 (100) | 0.67 (0.58; 0.75) 1.00 | |

| Insomnia medicine | U = 8491.500; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (17.6) | 21 (30.9) | 17 (25.0) | 18 (26.5) | 68 (100) | 1.60 (1.34; 1.86) 2.00 | |

| No | 301 (58.6) | 141 (27.4) | 42 (8.2) | 30 (5.8) | 514 (100) | 0.61 (0.54; 0.69) 0.00 | |

| Anxiety medicine | U = 14,213.500; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 29 (29) | 25 (25.0) | 20 (20.0) | 26 (26.0) | 100 (100) | 1.43 (1.20; 1.66) 1.00 | |

| No | 284 (58.9) | 137 (28.4) | 39 (8.1) | 22 (4.6) | 482 (100) | 0.58 (0.51; 0.66) 0.00 | |

| Depression medicine | U = 11,426.000; p < 0.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (20.6) | 29 (29.9) | 19 (19.6) | 29 (29.9) | 97 (100) | 1.59 (1.36; 1.81) 1.00 | |

| No | 293 (60.4) | 133 (27.4) | 40 (8.2) | 19 (3.9) | 485 (100) | 0.56 (0.48; 0.63) 0.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Condinho, M.; Ramalhinho, I.; Vaz-Velho, C.; Sinogas, C. Mental Health Evaluation in Community Pharmacies—A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030089

Condinho M, Ramalhinho I, Vaz-Velho C, Sinogas C. Mental Health Evaluation in Community Pharmacies—A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleCondinho, Mónica, Isabel Ramalhinho, Catarina Vaz-Velho, and Carlos Sinogas. 2024. "Mental Health Evaluation in Community Pharmacies—A Cross-Sectional Study" Pharmacy 12, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030089

APA StyleCondinho, M., Ramalhinho, I., Vaz-Velho, C., & Sinogas, C. (2024). Mental Health Evaluation in Community Pharmacies—A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy, 12(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030089