The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist in the Identification of Potentially Inadequate Drugs Prescribed to the Geriatric Population in Low-Resource Settings Using the Beers Criteria: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Patients and Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Population Ageing 2019, United Nations New York. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- World Population Ageing 2020, United Nations New York. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Halli-Tierney, A.D.; Scarbrough, C.; Carroll, D. Polypharmacy: Evaluating Risks and Deprescribing. Am. Fam. Physician. 2019, 100, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Parish, A.L. Polypharmacy and Medication Management in Older Adults. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 52, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrall, D.; Just, K.S.; Schmid, M.; Schmid, M.; Stingl, J.C.; Sachs, B. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A retrospective comparative analysis of spontaneous reports to the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarqouni, L.; Palagama, S.; Chai, J.; Sivananthajothy, P.; Pathirana, T.; Bakhit, M.; Arab-Zozani, M.; Ranakusuma, R.; Cardona, M.; Scott, A.; et al. Overuse of medications in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 36–61D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjarlamudi, H.B. Polytherapy and drug interactions in elderly. J. Midlife Health 2016, 7, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, C.P.; Tremp, R.; Hersberger, K.E.; Lampert, M.L. Inappropriate prescribing: A systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, D.M.; Cooper, J.W.; Wade, W.E.; Waller, J.L.; Maclean, J.R.; Beers, M.H. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, S.; Abdi, A.M.; Uzan, A.; Basgut, B. Applying Beers Criteria for Elderly Patients to Assess Rational Drug Use at a University Hospital in Northern Cyprus. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2019, 11, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, M.F.; Sulaiman, S.A.S.; Al Jeraisy, M.; Balubaid, H. The impact of a combined intervention program: An educational and clinical pharmacist’s intervention to improve prescribing pattern in hospitalized geriatric patients at King Abdulaziz Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, C.; Gama, J.; Rodrigues, M.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G. Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Potential Prescribing Omissions in Elderly Patients Receiving Post-Acute and Long-Term Care: Application of Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment Criteria. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 747523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinman, M.A.; Beizer, J.L.; DuBeau, C.E.; Laird, R.D.; Lundebjerg, N.E.; Mulhausen, P. How to Use the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria-A Guide for Patients, Clinicians, Health Systems, and Payors. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How to Use the AGS 2019 Beers Criteria® A Guide for Patients Clinicians, Health Systems and Payors. A Clinician Education Tool. Teaching Slides. Available online: https://geriatricscareonline.org/toc/how-to-use-theags-2019-beers-criteria/S004 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2227–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.A. Falling through the cracks: Challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, K.W.; Char, C.W.T.; Yip, A.Y.F. A review on interventions to reduce medication discrepancies or errors in primary or ambulatory care setting during care transition from hospital to primary care. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.M.; Brener, S.S.; Gunraj, N.; Huo, C.; Bierman, A.S.; Scales, D.C.; Bajcar, J.; Zwarenstein, M.; Urbach, D.R. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA 2011, 306, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileff, H.M.; Whitten, L.E.; Pink, J.A.; Goldsworthy, S.J.; Angley, M.T. The effect on medication errors of pharmacists charting medication in an emergency department. Pharm. World Sci. 2009, 31, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinewine, A.; Swine, C.; Dhillon, S.; Lambert, P.; Nachega, J.B.; Wilmotte, L.; Tulkens, P.M. Effect of a collaborative approach on the quality of prescribing for geriatric inpatients: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboli, P.J.; Hoth, A.B.; McClimon, B.J.; Schnipper, J.L. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: A systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, N.; Ali, K.; Davies, J.G.; Rajkumar, C. Do the 2015 Beers Criteria predict medication-related harm in older adults? Analysis from a multicentre prospective study in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2019, 28, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tian, F. Potentially inappropriate medications in older Chinese outpatients based on the Beers criteria and Chinese criteria. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 991087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H.; Dong, N.; Zhang, H. Potentially inappropriate medications in Chinese older adults: A comparison of two updated Beers criteria. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanović, G. Procena Adekvatnosti Propisivanja Terapije Kod Starih Osoba sa Kardiovaskularnim Bolestima. Ph.D. Dissertation, Univerzitet u Kragujevcu, Kragujevac, Serbia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Díez, R.; Cadenas, R.; Susperregui, J.; Sahagún, A.M.; Fernández, N.; García, J.J.; Sierra, M.; López, C. Potentially Inappropriate Medication and Polypharmacy in Nursing Home Residents: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.G.; Weymann, D.; Pratt, B.; Smolina, K.; Gladstone, E.J.; Raymond, C.; Mintzes, B. Sex differences in the risk of receiving potentially inappropriate prescriptions among older adults. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanović, M.; Vuković, M.; Jovanović, M.; Dimitrijević, S.; Radenković, M. Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Belgrade, Serbia Nursing Home Residents: A Comparison of Two Approaches. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 44, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, A.; Alaama, T.; Alomran, Y.; Al-Jedai, A.; Almudaiheem, H.; Watfa, G. Potentially inappropriate medications in older patients based on Beers criteria: A cross-sectional study of a family medicine practice in Saudi Arabia. BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20X101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, F.; Bian, M.; Yang, K. Relationship Between Potentially Inappropriate Medications and The Risk of Hospital Readmission and Death in Hospitalized Older Patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, C. Inappropriate benzodiazepine use in elderly patients and its reduction. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, E27–E28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.M.; Laetsch, D.C.; Chen, L.J.; Holleczek, B.; Meid, A.D.; Brenner, H.; Schöttker, B. Comparison of Five Lists to Identify Potentially Inappropriate Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Older Adults. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1962–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Medicines according to the Beers criteria are potentially inappropriate, not definitely inappropriate. |

| 2 | Read the explanation of the recommendation for each criterion. The warnings and instructions given there are important. |

| 3 | Understand why drugs are included in the list according to the Beers criteria and adjust the approach to drugs accordingly. |

| 4 | Optimal application of the Beers criteria includes the identification of potentially inappropriate drugs and, where possible, offers safer non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies. |

| 5 | The Beers criteria should be the starting point for a comprehensive process of identifying and improving the suitability and safety of medicines. |

| 6 | Access to drugs included in the Beers criteria should not be unduly restricted by prior authorization and/or health plan environmental policies. |

| 7 | Beers criteria are not equally applicable to all countries. |

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 76.31 ± 7.04 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 36 (54.50) |

| I age group (65–75 years), n (%) | 33 (50.00) |

| II age group (>75 years), n (%) | 33 (50.00) |

| Neurology, n (%) | 31 (46.97) |

| Cardiology, n (%) | 16 (24.24) |

| Pulmology, n (%) | 19 (28.79) |

| Characteristic | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurology (N = 31) | Cardiology (N = 16) | Pulmology (N = 19) | Total | |

| Number of prescribed medicines, n (%) | 307 (42.23) | 179 (24.62) | 241 (33.15) | 727 (100.00) |

| Female, n (%) | 166 (22.83) | 79 (10.87) | 83 (11.42) | 328 (45.12) |

| Male, n (%) | 141 (19.39) | 100 (13.76) | 158 (21.73) | 399 (54.88) |

| I age group (65–75 years), n (%) | 152 (20.91) | 99 (13.62) | 124 (17.06) | 375 (51.58) |

| II age group (>75 years), n (%) | 155 (21.32) | 80 (11.00) | 117 (16.10) | 352 (48.42) |

| Neurology | Cardiology | Pulmonology | Total PIMs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 46 (22.55) | 22 (10.78) | 20 (9.80) | 88 (43.14) |

| Male, n (%) | 41 (20.10) | 29 (14.22) | 46 (22.55) | 116 (56.86) |

| I age group (65–75 years), n (%) | 39 (19.12) | 26 (12.75) | 32 (15.67) | 97 (47.55) |

| II age group (>75 years), n (%) | 48 (23.53) | 25 (12.25) | 34 (16.67) | 107 (52.45) |

| PIMs, n (%) | 87 (42.65) | 51 (25.00) | 66 (32.35) | 204 (100.00) |

| Mean (±SD) | r | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

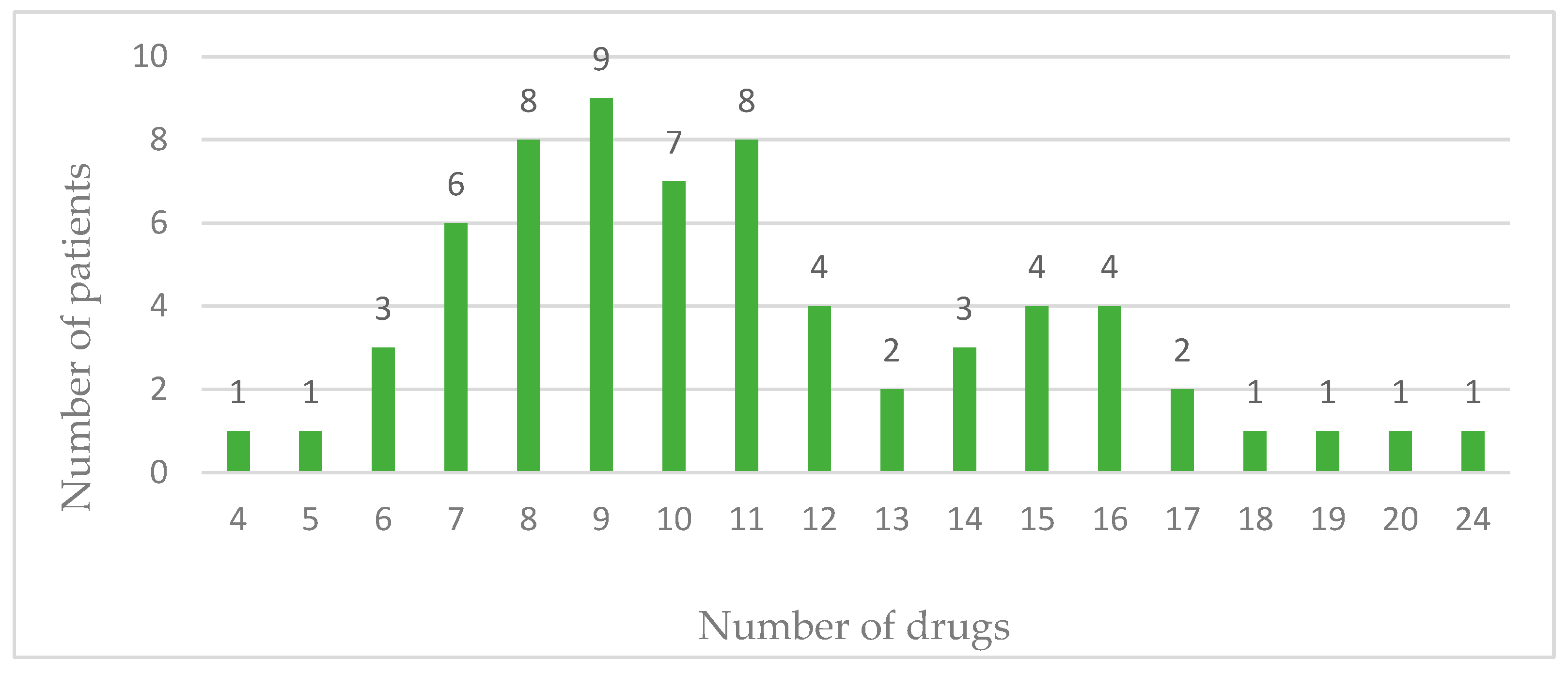

| Number of drugs | 11.02 (3.94) | 0.59 | <0.01 |

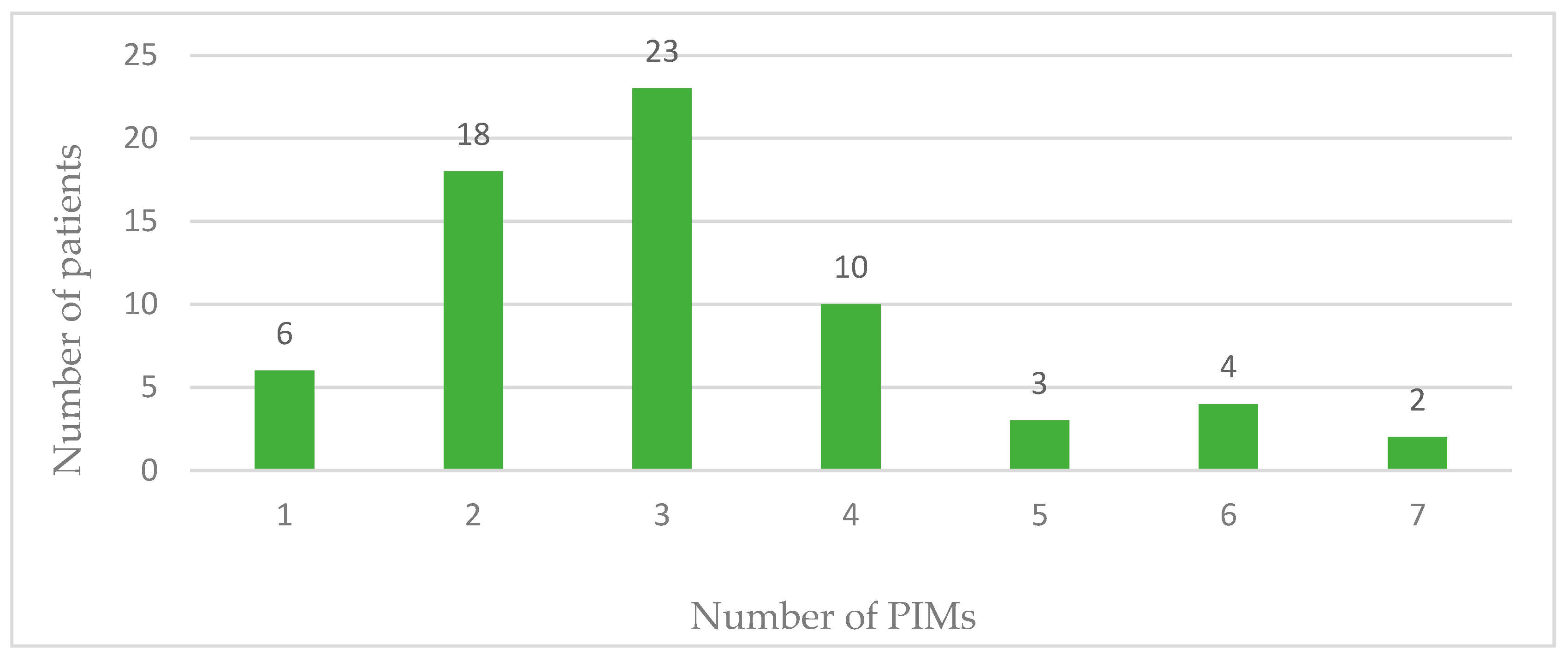

| Number of PIMs | 3.09 (1.42) |

| ATC Class of Medicines | Number of Medicines (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| C | Medicines that affect the cardiovascular system | 91 (44.61) |

| A | Medicines that affect the alimentary tract and metabolism | 41 (20.10) |

| N | Medicines that affect the nervous system | 31 (15.19) |

| M | Medicines that affect the musculoskeletal system | 28 (13.73) |

| B | Medicines with effects on blood and blood organs | 7 (3.43) |

| H | Hormonal preparations for systemic use, excluding sex hormones and insulin | 5 (2.45) |

| J | Antiinfectives for systematic use | 1 (0.49) |

| Drug | Number of PIMs, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Furosemide | 37 (18.14) |

| Pantoprazole | 34 (16.67) |

| Ketoprofen | 23 (11.27) |

| Spironolactone | 22 (10.78) |

| Bromazepam | 20 (9.80) |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 10 (4.90) |

| Digoxin | 9 (4.41) |

| Diazepam | 5 (2.45) |

| Metoclopramide | 5 (2.45) |

| Amiodaron | 4 (1.96) |

| Diclofenac | 4 (1.96) |

| Enoxaparin | 4 (1.96) |

| Indapamide | 3 (1.47) |

| Methylprednisolone | 3 (1.47) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 2 (0.98) |

| Amiloride | 2 (0.98) |

| Glimepiride | 2 (0.98) |

| Methyldopa | 2 (0.98) |

| Sertraline | 2 (0.98) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 (0.49) |

| Dexamethasone | 1 (0.49) |

| Enalapril | 1 (0.49) |

| Haloperidol | 1 (0.49) |

| Clonazepam | 1 (0.49) |

| Nimesulide | 1 (0.49) |

| Paroxetine | 1 (0.49) |

| Prednisone | 1 (0.49) |

| Promazine | 1 (0.49) |

| Ramipril | 1 (0.49) |

| Rivaroxaban | 1 (0.49) |

| Potentially Inappropriate Medicines | Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 3 (2–4) | <0.01 * |

| After intervention | 2 (1–3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovačević, T.; Savić Davidović, M.; Barišić, V.; Fazlić, E.; Miljković, S.; Djajić, V.; Miljković, B.; Kovačević, P. The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist in the Identification of Potentially Inadequate Drugs Prescribed to the Geriatric Population in Low-Resource Settings Using the Beers Criteria: A Pilot Study. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030084

Kovačević T, Savić Davidović M, Barišić V, Fazlić E, Miljković S, Djajić V, Miljković B, Kovačević P. The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist in the Identification of Potentially Inadequate Drugs Prescribed to the Geriatric Population in Low-Resource Settings Using the Beers Criteria: A Pilot Study. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(3):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovačević, Tijana, Maja Savić Davidović, Vedrana Barišić, Emir Fazlić, Siniša Miljković, Vlado Djajić, Branislava Miljković, and Peđa Kovačević. 2024. "The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist in the Identification of Potentially Inadequate Drugs Prescribed to the Geriatric Population in Low-Resource Settings Using the Beers Criteria: A Pilot Study" Pharmacy 12, no. 3: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030084

APA StyleKovačević, T., Savić Davidović, M., Barišić, V., Fazlić, E., Miljković, S., Djajić, V., Miljković, B., & Kovačević, P. (2024). The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist in the Identification of Potentially Inadequate Drugs Prescribed to the Geriatric Population in Low-Resource Settings Using the Beers Criteria: A Pilot Study. Pharmacy, 12(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030084