Empowering Pharmacists: Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis through a Public Health Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

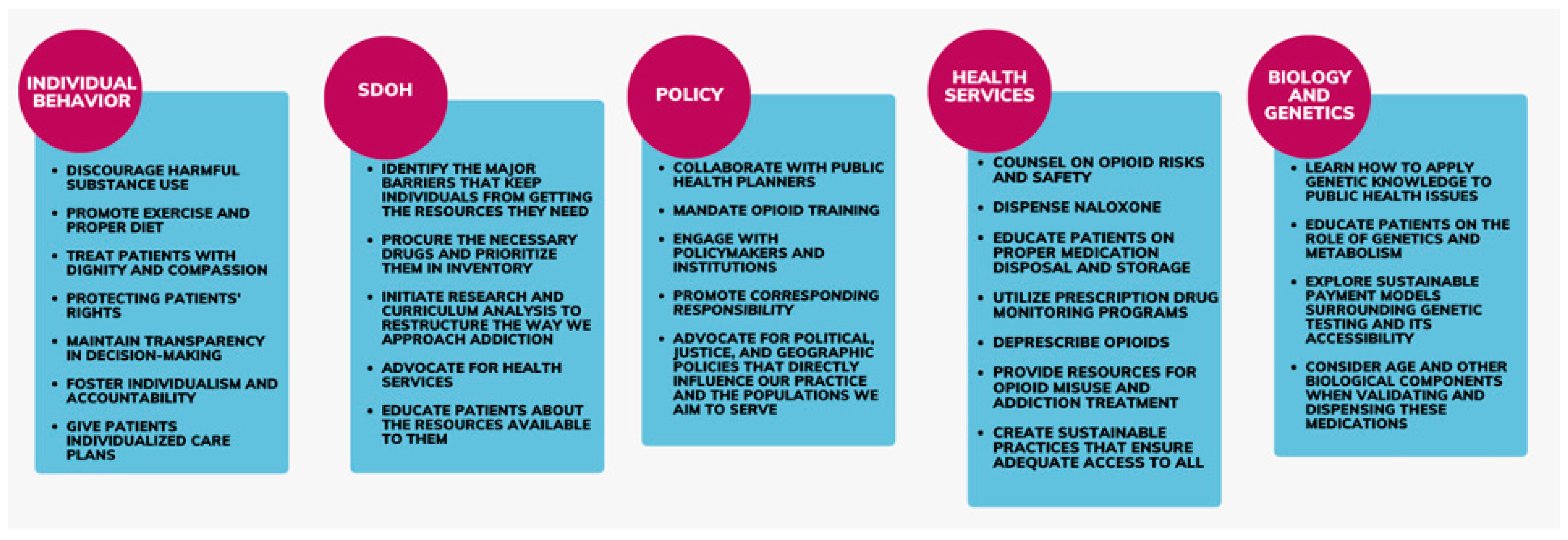

2. Pharmacists’ Roles in Addressing Health Determinants in the Opioid Crisis

2.1. Individual Behavior

- Education and Counseling: Provide personalized education on opioid use, safe storage, and disposal. Implement motivational interviewing techniques to support behavior change.

- Naloxone Training: Equip pharmacists with comprehensive naloxone training to educate patients and caregivers on its use.

- Screening Tools: Utilize validated screening tools to identify patients at risk of opioid misuse and provide early interventions.

2.2. Social Determinants of Health

2.2.1. Mitigating Barriers

2.2.2. Addressing Stigma

2.2.3. Community Outreach and Education

- Community Outreach: Develop partnerships with local health organizations, community centers, and social services to enhance resource distribution and support networks for individuals struggling with opioid use.

- Stigma Reduction Initiatives: Organize workshops and training sessions aimed at reducing stigma within the pharmacy practice. Encourage open discussions about addiction and recovery to foster empathy and understanding.

- Advocacy for Policy Changes: Work with professional pharmacy organizations and health policy advocates to push for legislative changes that empower pharmacists to engage more actively in public health initiatives.

- Curriculum Enhancements: Collaborate with pharmacy schools to ensure that training on social determinants and stigma is a core part of the curriculum. Provide continuing education opportunities for current practitioners to stay updated on the best practices.

2.3. Policymaking

- Policy Advocacy: Engage in advocacy efforts to influence legislation and regulatory changes that enhance pharmacists’ roles in opioid stewardship.

- Clear Guidelines: Collaborate with policymakers to ensure pharmacists’ perspectives are included in opioid-related legislation to develop and disseminate clear, actionable guidelines for pharmacists based on national and state policies.

2.4. Health Services

- Training and Education: Ensure pharmacists receive training in deprescribing techniques, including patient communication strategies and the management of withdrawal symptoms.

- Advocate for an Expanded Scope of Practice: Advocate for an expanded scope of practice to allow pharmacists to initiate MAT.

- Develop Effective Referral Protocols: Develop protocols for effective referral and follow-up processes.

2.5. Biology and Genetics

- Incorporate Pharmacogenomics Training: Integrate pharmacogenomics education into PharmD programs and continuing education curricula to equip pharmacists with the necessary skills and knowledge to apply genetic testing in practice effectively.

- Promote Research Participation: Encourage pharmacists to engage in research endeavors focusing on personalized medicine approaches, including pharmacogenomics, to contribute to the advancement of evidence-based practice.

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services the Opioid Crisis and the Black/African American Population: An Urgent Issue. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Black-African-American-Population-An-Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-001 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs What Is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic? Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Injury Center, CDC Drug Overdose. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Bratberg, J.P.; Smothers, Z.P.W.; Collins, K.; Erstad, B.; Ruiz Veve, J.; Muzyk, A.J. Pharmacists and the opioid crisis: A narrative review of pharmacists’ practice roles. JACCP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.; Hughes, C. Pharmacists and harm reduction: A review of current practices and attitudes. Can. Pharm. J. CPJ 2012, 145, 124–127.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, G.; Chandra, R.N.; Ivey, M.F.; Khatri, C.S.; Nemire, R.E.; Quinn, C.J.; Subramaniam, V. ASHP Statement on the Pharmacist’s Role in Public Health. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2022, 79, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Public Health Association The Role of the Pharmacist in Public Health. Available online: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/07/13/05/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-public-health (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Meyerson, B.E.; Ryder, P.T.; Richey-Smith, C. Achieving Pharmacy-Based Public Health: A Call for Public Health Engagement. Public Health Rep. 2013, 128, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Buprenorphine Guidelines|OUD Treatment by Pharmacists. Available online: https://nabp.pharmacy/buprenorphine-guidelines/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Clinical Resources for Opioids. Available online: https://www.pharmacist.com/Practice/Patient-Care-Services/Opioid-Use-Misuse/Opioid-Clinical-Resources (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- American Pharmacists Association (APhA) APhA, Walmart Provide Free Opioid Training to Pharmacists, Technicians. Available online: https://www.drugtopics.com/view/apha-walmart-provide-free-opioid-training-to-pharmacists-techs (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Cheung, Y.W. Substance abuse and developments in harm reduction. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000, 162, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk, M.; Coulter, R.W.S.; Egan, J.E.; Fisk, S.; Reuel Friedman, M.; Tula, M.; Kinsky, S. Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm. Reduct. J. 2017, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, T.; Frey, M.; Chewning, B. Pharmacist Services in the Opioid Crisis: Current Practices and Scope in the United States. Pharm. J. Pharm. Educ. Pract. 2019, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzyk, A.; Smothers, Z.P.W.; Collins, K.; MacEachern, M.; Wu, L.-T. Pharmacists’ attitudes toward dispensing naloxone and medications for opioid use disorder: A scoping review of the literature. Subst. Abuse 2019, 40, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larochelle, M.R.; Slavova, S.; Root, E.D.; Feaster, D.J.; Ward, P.J.; Selk, S.C.; Knott, C.; Villani, J.; Samet, J.H. Disparities in Opioid Overdose Death Trends by Race/Ethnicity, 2018–2019, From the HEALing Communities Study. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1851–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohler, R. Addressing the Opioid Crisis through Social Determinants of Health: What Are Communities Doing? Opioid Policy Research Collaborative: Waltham, MA, USA, 2021; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, N.; Beletsky, L.; Ciccarone, D. Opioid Crisis: No Easy Fix to Its Social and Economic Determinants. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, M.L.; McMahan, K.B.; Chichester, K.R.; Galbraith, J.W.; Cropsey, K.L. Attitudes and availability: A comparison of naloxone dispensing across chain and independent pharmacies in rural and urban areas in Alabama. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 74, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.H.; Hur, S.; Young, H.N. Assessment of naloxone availability in Georgia community pharmacies. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. JAPhA 2020, 60, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, A.; Bauer, E.; Gallagher, S.; Karstens, B.; Lavoie, L.; Ahrens, K.; O’Connor, A. Experiences of stigma among individuals in recovery from opioid use disorder in a rural setting: A qualitative analysis. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2021, 130, 108488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drugs; Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice 21 CFR 1306.04—Purpose of Issue of Prescription. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-II/part-1306/subject-group-ECFR1eb5bb3a23fddd0/section-1306.04 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) North Carolina’s Opioid Action Plan|NCDHHS. 2017. Available online: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/opioid-epidemic/north-carolinas-opioid-action-plan (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. Naloxone Access Summary of State Laws; Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; 193p. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Drug Evaluation. Opioid Analgesic Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-drug-class/opioid-analgesic-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategy-rems (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Barlas, S. Pharmacists Step Up Efforts to Combat Opioid Abuse. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 369–401. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Board of Medicine Controlled Substances CE Requirements. Available online: https://www.dhp.virginia.gov/Boards/Medicine/AbouttheBoard/News/announcements/Content-429369-en.html (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Harm Reduction. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) Pharmacists. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/implementation-toolkits/pharmacists.html (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Valliant, S.N.; Burbage, S.C.; Pathak, S.; Urick, B.Y. Pharmacists as accessible health care providers: Quantifying the opportunity. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2022, 28, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Farrell, B. Deprescribing: What Is It and What Does the Evidence Tell Us? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2013, 66, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R.A.; Zule, W.A.; Hurt, C.B.; Evon, D.M.; Rhea, S.K.; Carpenter, D.M. Pharmacist attitudes and provision of harm reduction services in North Carolina: An exploratory study. Harm. Reduct. J. 2021, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, A. Pharmacists Hesitant to Dispense Lifesaving Overdose Drug Naloxone. Available online: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180106/NEWS/180109948/pharmacists-hesitant-to-dispense-lifesaving-overdose-drug-naloxone (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Kurian, S.; Baloy, B.; Baird, J.; Burstein, D.; Xuan, Z.; Bratberg, J.; Tapper, A.; Walley, A.; Green, T.C. Attitudes and perceptions of naloxone dispensing among a sample of Massachusetts community pharmacy technicians. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutnick, A.; Cooper, E.; Dodson, C.; Bluthenthal, R.; Kral, A.H. Pharmacy syringe purchase test of nonprescription syringe sales in San Francisco and Los Angeles in 2010. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2013, 90, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Behrends, C.N.; Lu, X.; Corry, G.J.; LaKosky, P.; Prohaska, S.M.; Glick, S.N.; Kapadia, S.N.; Perlman, D.C.; Schackman, B.R.; Des Jarlais, D.C. Harm reduction and health services provided by syringe services programs in 2019 and subsequent impact of COVID-19 on services in 2020. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 232, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) Pharmacists: On the Front Lines: Addressing Prescription Opioid Abuse and Overdose. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/43485 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Bertilsson, L.; Dahl, M.-L.; Dalén, P.; Al-Shurbaji, A. Molecular genetics of CYP2D6: Clinical relevance with focus on psychotropic drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugada, D.; Lorini, L.F.; Fumagalli, R.; Allegri, M. Genetics and Opioids: Towards More Appropriate Prescription in Cancer Pain. Cancers 2020, 12, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Gutiérrez, M.J.; Martínez-Cengotitabengoa, M.; Sáez de Adana, E.; Cano, A.I.; Martínez-Cengotitabengoa, M.T.; Besga, A.; Segarra, R.; González-Pinto, A. Relationship between the use of benzodiazepines and falls in older adults: A systematic review. Maturitas 2017, 101, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudin, J.A.; Mogali, S.; Jones, J.D.; Comer, S.D. Risks, Management, and Monitoring of Combination Opioid, Benzodiazepines, and/or Alcohol Use. Postgrad. Med. 2013, 125, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armistead, L.T.; Hughes, T.D.; Larson, C.K.; Busby-Whitehead, J.; Ferreri, S.P. Integrating targeted consultant pharmacists into a new collaborative care model to reduce the risk of falls in older adults owing to the overuse of opioids and benzodiazepines. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 61, E16–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niznik, J.D.; Collins, B.J.; Armistead, L.T.; Larson, C.K.; Kelley, C.J.; Hughes, T.D.; Sanders, K.A.; Carlson, R.; Ferreri, S.P. Pharmacist interventions to deprescribe opioids and benzodiazepines in older adults: A rapid review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2022, 18, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niznik, J.; Ferreri, S.P.; Armistead, L.; Urick, B.; Vest, M.-H.; Zhao, L.; Hughes, T.; McBride, J.M.; Busby-Whitehead, J. A deprescribing medication program to evaluate falls in older adults: Methods for a randomized pragmatic clinical trial. Trials 2022, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hughes, T.D.; Nowak, J.; Sottung, E.; Mustafa, A.; Lingechetty, G. Empowering Pharmacists: Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis through a Public Health Lens. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030082

Hughes TD, Nowak J, Sottung E, Mustafa A, Lingechetty G. Empowering Pharmacists: Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis through a Public Health Lens. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(3):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030082

Chicago/Turabian StyleHughes, Tamera D., Juliet Nowak, Elizabeth Sottung, Amira Mustafa, and Geetha Lingechetty. 2024. "Empowering Pharmacists: Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis through a Public Health Lens" Pharmacy 12, no. 3: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030082

APA StyleHughes, T. D., Nowak, J., Sottung, E., Mustafa, A., & Lingechetty, G. (2024). Empowering Pharmacists: Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis through a Public Health Lens. Pharmacy, 12(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030082