Answering the Call for Community Pharmacists to Improve Healthcare Delivery to Trans and Gender Diverse People: Guide for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating an Online Education Program in Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- Transgender Healthcare—Language, terminology, and key healthcare issues.

- Gender-affirming therapies.

- Case Studies in trans and gender diverse healthcare.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Application of Knowles Six Principles to the Design of the Program

- Adults are self-directed: Adult learners favour taking responsibility for their learning [27]. Therefore, it was essential to design a learning program that respects their autonomy and provides an opportunity to complete the modules in the participant’s own time.

- Experience: Adults use their experiences to shape their learning [27]. Pharmacists have extensive experience in providing care to various clients in the pharmacy. Drawing on these experiences provided a foundation for new learning about TGD healthcare and enhanced their understanding of new content by establishing links to their previous knowledge and experience.

- Readiness to learn: Adult learners learn when they are ready to learn and when the learning benefits their personal or professional goals [27]. The earlier research indicated that most pharmacists desired to improve their practice of providing care to TGD people [6,7]. Capitalizing on readiness enabled pharmacists to learn from theory as well as practical strategies to improve their competence in TGD healthcare.

- Problem-centred orientation: Adult learners want to see if the new learning can resolve their current problems [27]. This program design Including communication strategies, TGD healthcare knowledge, and day-to-day pharmacy practice scenarios enabled participants to immediately implement changes to their practice.

- Motivation to learn: For adult learners, intrinsic motivators such as improved self-esteem, job satisfaction, confidence and personal growth may play vital role in motivating them to learn new things [27]. Participation in the program was voluntary relying on the participant’s internal motivation to participate and complete the program. The participants received a certificate on completing the program and could count the program hours (up to eight hours) towards their continuing professional education (CPE) points, providing additional external motivation to complete this program.

- The need to know: Adults actively engage in training programs that they perceive relevant to their practice [27]. The needs analysis showed that the pharmacist participants in this program envisaged that learning new concepts and strategies in TGD care would be relevant to their current practice [6,7].

References

- Cheung, A.S.; Wynne, K.; Erasmus, J.; Murray, S.; Zajac, J.D. Position statement on the hormonal management of adult transgender and gender diverse individuals. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Is Trans? ACON. Available online: https://www.transhub.org.au/101/what-is-trans (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Chaudhary, S.; Ray, R.; Glass, B.D. “Treat us as a person”: A narrative inquiry of experiences and expectations of interactions with pharmacists and pharmacy staff among people who are transgender. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2022, 8, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, N.J.W.; Batra, P.; Misiolek, B.A.; Rockafellow, S.; Tupper, C. Transgender/gender nonconforming adults’ worries and coping actions related to discrimination: Relevance to pharmacist care. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2019, 76, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, K.; Hilera-Botet, C.R.; Vega-Vélez, D.; Salgado-Crespo, V.M.; Santiago, D.; Hernández-Agosto, J.; Muñoz-Burgos, A.; Cajigas, Z.; Martínez-Vélez, J.J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, C.E. Readiness to provide pharmaceutical care to transgender patients: Perspectives from pharmacists and transgender individuals. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Ray, R.; Glass, B. Do the attitudes and practices of Australian pharmacists reflect a need for education and training to provide care for people who are transgender? IJPP 2023, riad077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Ray, R.; Glass, B.D. “I don’t know much about providing pharmaceutical care to people who are transgender”: A qualitative study of experiences and attitudes of pharmacists. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 9, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretherton, I.; Thrower, E.; Zwickl, S.; Wong, A.; Chetcuti, D.; Grossmann, M.; Zajac, J.D.; Cheung, A.S. The Health and Well-Being of Transgender Australians: A National Community Survey. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Ray, R.; Glass, B. Pharmacists’ role in transgender healthcare: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocohoba, J. Pharmacists caring for transgender persons. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2017, 74, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, J.S.; Jann, M.W. The evolving role of pharmacists in transgender health care. Transgender Health 2019, 4, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Hughto, J.M.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfern, J.S.; Sinclair, B. Improving health care encounters and communication with transgender patients. J. Commun. Healthc. 2014, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Professional Practice Standards Version 6; Pharmaceutical Society of Australia: Canberra, Australia. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/practice-support-industry/pps/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Code of Ethics for Pharmacists; The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/practice-support-industry/ethics/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Equality Position Statement; The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Available online: https://my.psa.org.au/s/article/Equality-Position-Statement (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Frazier, C.C.; Nguyen, T.L.; Gates, B.J.; McKeirnan, K.C. Teaching transgender patient care to student pharmacists. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, C.; Chen, L.-W.; Conklin, J. Addition of Care for Transgender-Related Patient Care into Doctorate of Pharmacy Curriculum: Implementation and Preliminary Evaluation. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostroff, J.L.; Ostroff, M.L.; Billings, S.; Nemec, E.C. Integration of transgender care into a pharmacy therapeutics curriculum. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhill, A.L.; Mathews, J.L.; Fearing, S.; Gainsburg, J. A transgender health care panel discussion in a required diversity course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014, 78, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa Vega, J.; Carlo, E.; Rodríguez-Ochoa, A.; Hernández-Agosto, J.; Santiago Quiñones, D.; Cabrera-Candelaria, D.; Rodríguez-Díaz, C.E.; Melin, K. Educational intervention to improve pharmacist knowledge to provide care for transgender patients. Pharm. Pract. Off. J. GRIPP (Glob. Res. Inst. Pharm. Pract.) 2020, 18, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.; Seung, H.; Layson-Wolf, C. Student pharmacists’ perceptions of transgender health management. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019, 11, 1254–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, L.K.B.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, A.; Balandin, S.; Sigafoos, J.; Reed, V.A. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

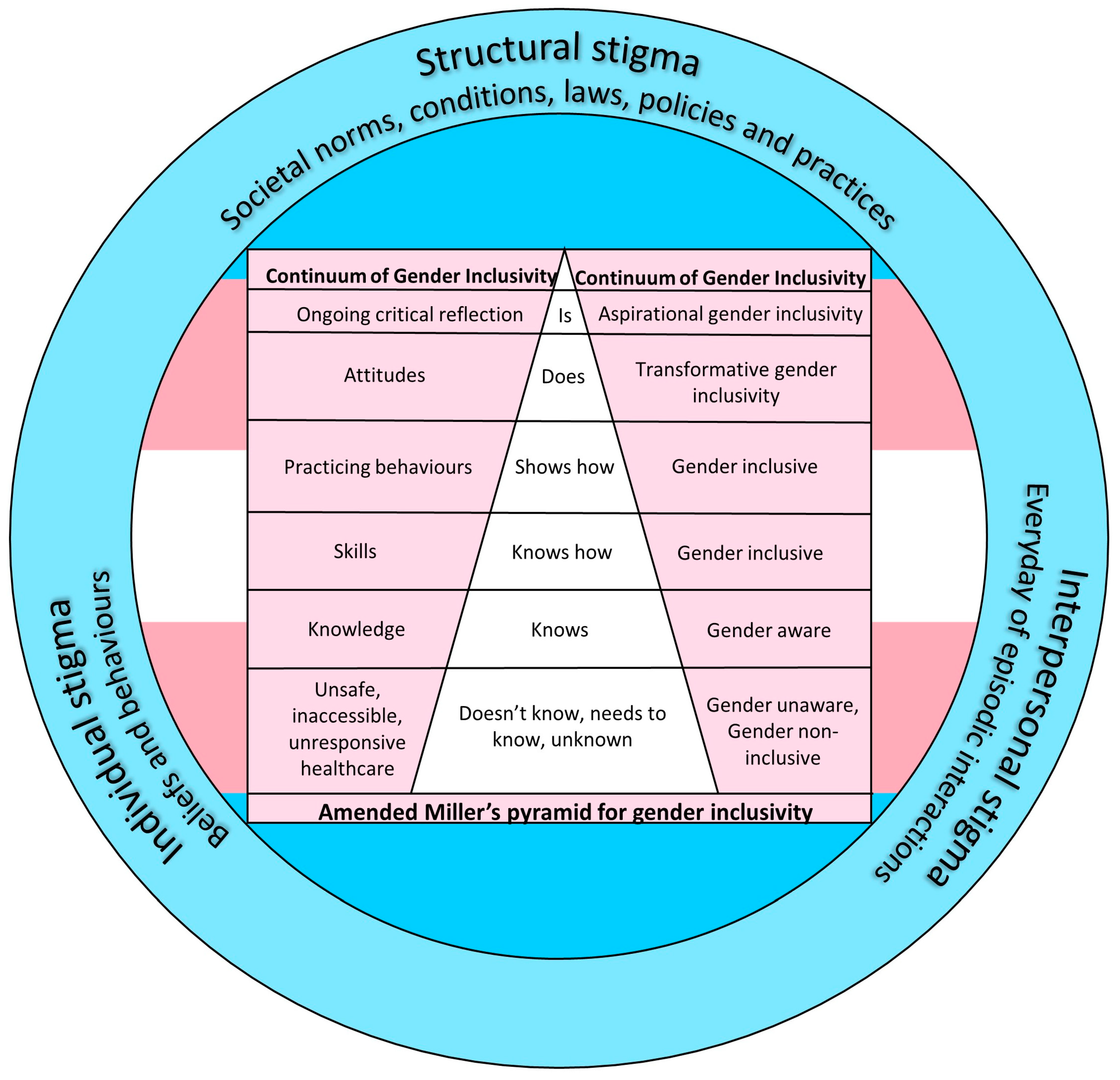

- Cruess, R.L.; Cruess, S.R.; Steinert, Y. Amending Miller’s Pyramid to Include Professional Identity Formation. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, W. Andragogy. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Online Education; Published online; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Sauzendoaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Brumpton, K.; Ward, R.; Evans, R.; Neill, H.; Woodall, H.; McArthur, L.; Sen Gupta, T. Assessing cultural safety in general practice consultations for Indigenous patients: Protocol for a mixed methods sequential embedded design study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restar, A.J.; Sherwood, J.; Edeza, A.; Collins, C.; Operario, D. Expanding Gender-Based Health Equity Framework for Transgender Populations. Transgender Health 2021, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, C.; McNaire, R.; Callegari, B.; Ansara, G.; Appleton, B.; August, M.; Carastathis, G.; Cook, T.; Erasmus, J.; Felmingham, K.; et al. The Trans GP Training. Available online: https://nwmphn.org.au/health-systems-capacity-building/trans-gp-module/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Trans GP Education Day; Australian Professional Association for Trans Health: Northern Territory, Australia; Available online: https://portalapp.ashm.eventsair.com/VirtualAttendeePortal/auspath-gp-day-2020/auspath-gp-edu-day-2020/login (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- WPATH 26th Scientific Symposium; World Professional Association for Transgender Health: East Dundee, IL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Upcoming%20Conferences/2020/WPATH%20Main%20Symposium%20Schedule_FINAL_FINAL.pdf?_t=1604501102 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Qualtrics. Wecome to XM. Available online: https://jcu.qualtrics.com/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Newsome, C.C.; Gilmer, A. Strategies to Bring Transgender and Non-binary Health Care into Pharmacy Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 8283–8322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Determinants | Module | Performance Objectives | Practical Strategy * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness—Culture and Healthcare Needs | Transgender Healthcare—Language, Terminology, and Key Health Issues | To understand the language and terminology for appropriate communication with trans and gender diverse people. To describe how to create a welcoming and inclusive pharmacy environment for trans and gender diverse people. To identify key health issues faced by trans and gender diverse populations. To understand the role of pharmacists in trans and gender diverse healthcare. | Partnership with trans and gender diverse people and pharmacists. Videos with trans and gender diverse people to incorporate their lived experiences in the program. Pharmacists and trans and gender diverse people pharmacy interaction videos. Written information. |

| Knowledge | Gender Affirming Therapies | To discuss the common approaches for gender affirmation. To describe the role of hormonal and surgical therapies in gender affirmation. To identify potential drug interactions. To understand the effect of hormonal therapy on laboratory values. | Written information. |

| Skills | Case Studies Transgender Healthcare | To apply the learning from Modules 1 and 2 to address the problems and challenges faced in providing care to trans and gender diverse people, making decisions based on the evidence given. | Partnership with trans and gender diverse people and pharmacists. Case studies. Videos demonstrating appropriate counselling and interactions with trans and gender diverse people in pharmacy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaudhary, S.; Ray, R.A.; Glass, B.D. Answering the Call for Community Pharmacists to Improve Healthcare Delivery to Trans and Gender Diverse People: Guide for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating an Online Education Program in Australia. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12010007

Chaudhary S, Ray RA, Glass BD. Answering the Call for Community Pharmacists to Improve Healthcare Delivery to Trans and Gender Diverse People: Guide for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating an Online Education Program in Australia. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaudhary, Swapna, Robin A. Ray, and Beverley D. Glass. 2024. "Answering the Call for Community Pharmacists to Improve Healthcare Delivery to Trans and Gender Diverse People: Guide for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating an Online Education Program in Australia" Pharmacy 12, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12010007

APA StyleChaudhary, S., Ray, R. A., & Glass, B. D. (2024). Answering the Call for Community Pharmacists to Improve Healthcare Delivery to Trans and Gender Diverse People: Guide for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating an Online Education Program in Australia. Pharmacy, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12010007