Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians’ Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Research Setting

2.3. Participant Selection

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Interview Guides

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme One: Inconsistencies in MMA Practice

3.1.1. Pharmacists’ Absence and Lack of Standard Procedures for the Provision of Minor Ailment Services

“…many people come with a complaint of minor ailments to the pharmacy every day. However, the main obstacle is that the pharmacist is not always at service at the pharmacy. It is also impossible for me to work a full-time shift at the pharmacy…”(Pharm10)

“…In the afternoon, when the pharmacists are not in practice, many patients require self-medication, and we (the pharmacy technicians) have to serve them all, not the pharmacists because they are not in service…”(Tech6)

“Sometimes, I am in charge of serving patients (initially). Other times, it can be my wife (a pharmacist), the administrator, and staff (who graduated from pharmacy vocational high school or senior high school). Basically, anyone working in the pharmacy can be in charge of serving patients.”(Pharm6)

“SPG (sales promotion staff) will directly serve patients at the front door, welcome incoming patients, and offer their products to patients.”(Tech11)

“I always inform pharmacy technicians that whenever they are having certain issues, they can contact me (by phone or WhatsApp) because serving medicine cannot be done carelessly…”(Pharm10)

“If one pharmacist was having a day off, the other pharmacist will only serve in the afternoon shift…in case we need to ask anything, we can consult with a senior staff… we can call the pharmacist to consult the patient’s complaint according to their need.”(Tech11)

“The pharmacist here is freshly graduated and does not have full-time work at the pharmacy, so I never recommend consulting a pharmacist for patients….the pharmacist will consult me because I have worked in this field for nine years…”(Tech3)

3.1.2. Non-Qualified Assistants’ Involvement Providing Basic Services

“Non-qualified assistants are sometimes involved in providing pharmacy services to patients presenting with minor ailments, but they shall consult the pharmacist or pharmacy technicians for service provision.”(Pharm1)

“They (non-qualified assistants) cannot provide such service. The law has stipulated that they are not supposed to provide the service. However, during the peak hours at the pharmacy, non-qualified assistants (who collects the prescriptions or deliver medicines) will come to help us…”(Pharm3)

3.1.3. Inconsistent Education and Training of Pharmacy and Pharmacy Technician Students

“Back then, the lectures at the university only provided us with theoretical explanation without going to further detail regarding what we can experience during the practice…there was no special course on minor ailments since the materials related to minor ailments were covered in some units such as Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Science. Apart from that, there is a wide gap between theoretical aspects and practical aspects.”(Pharm9)

“I was not confident back then, because I had to learn everything from scratch (when graduated).”(Pharm6)

“I believe that confidence is more closely related to experience…Some universities may provide no clinical placement program for the undergraduate level…”(Pharm2)

“…there should be some kinds of training or seminars and internships with hands-on experience with patients because a mere theoretical practice will not prepare students with the real practices.”(Pharm3)

“…it is necessary to add a clinical placement at a community pharmacy, because in the past, clinical placements were only conducted in hospitals or in industries.”(Tech7)

“…clinical placement would be better if the duration was extended….ideally there should be a longer duration for fieldwork practice.”(Pharm4)

“….clinical placement should be made available at the undergraduate level and if possible, the duration should be increased to at least three months or one semester.”(Pharm2)

3.2. Theme Two: Lack of Understanding of the Scopes of Practice of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians

3.2.1. No Clear Demarcation between the Scope of Practice of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians

“There is no such difference (scope of practice) at my pharmacy. But there should be a difference. Patients are mostly served by both pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.”(Pharm1)

“Since I work in this pharmacy, there is no strict difference between the service provision for minor ailments that should be handled by a pharmacy technician or by a pharmacist. From my experience, the complaints of minor ailments are all the same…”(Tech2)

3.2.2. Inconsistencies in When to Refer Serious Minor Ailments to a Doctor

“…I shall refer some patients who suffer from shortness of breath and heartburn, complaints of pain in the left chest to see a doctor. In the case of a swollen leg, I will suggest the patient see the doctor.”(Pharm9)

“Whenever we have patients with complaints of diabetes and refuse to go to the doctor, I usually check their sugar levels and ask if they have shortness of breath. If the patient is only taking metformin, I suggest that they change their medicine because it did not downgrade their sugar levels.”(Tech3)

3.3. Theme Three: Provision of Prescription-Only Medicines for MMA

3.3.1. Commonly Purchased Medicines, including the Non-Prescribed Sales of Antibiotics and Its Existing Regulations

“…even though the patient came without a prescription, whenever their blood pressure turned out to be high, and they had never taken any medicine, usually I would give them a common blood pressure medicine such as amlodipine *.” * Labelled as prescription-only medicines.(Tech8)

“…we do serve to patients because antibiotics are affordable. You can get amoxicillin only for Rp.4500 (USD 0.30). Even you can have it only for Rp.2000 (USD 0.15).”(Pharm12)

“Yes, if they bring a sample of the medicine (antibiotics), they can easily get the medicine. Bringing a sample of the medicine means that they have used the medicine before.”(Tech6)

3.3.2. Source of Non-Prescribed Sale of Antibiotics

“In practice, even though my pharmacy does not sell antibiotics freely (supplied), it turns out that some midwives and nurses uncontrollably provide patients with antibiotics. They keep on providing patients with antibiotics…”(Pharm4)

“I saw some midwives and mantri (orderlies) providing some medicines that were out of their scope, and sometimes they gave the wrong medicine. Even worse, they also gave the patient who had a cardiac history with the medicine that contradicted the illness…”(Pharm12)

3.3.3. Patients Misconceptions about Antibiotics

“A common example that allows the provision of antibiotics is urinary tract infection…patients prefer to come directly to the pharmacy rather than check with the doctor. Pharmacists will usually suggest increasing broader spectrum of activity, such as giving urinary Urotractin * antibiotics.” * Antibiotic contains pipemidic acid.(Tech8)

“Patients will surely become upset. Instead, they will try to obtain antibiotics in other pharmacies. In their view, why cannot they have them at my pharmacy?”(Pharm12)

“I have encountered some obstacles like the provision of antibiotics, as previously mentioned. If I do not give it to the patients, they remain nagging about it.”(Tech12)

3.3.4. Pharmacy Technicians’ Commercial Interest Pushing the Sale of Non-Prescribed Antibiotics

“The poor condition of the pharmacy makes it unable to receive many prescriptions. Thus, the pharmacy had to sell antibiotics easily, and sell all medicines, both prescription-only medicines and antibiotics for profit.”(Tech5)

“I know that antibiotics should not be traded easily. Nonetheless, if we do not sell antibiotics, the pharmacy will not make a profit.”(Tech6)

3.3.5. Weak Enforcement of Regulations

“BPOM (the Indonesian National Agency of Food and Drug Control) only checks medicines without a logo. BPOM never asked about antibiotics in detail.”(Pharm9)

“Each representative from the pharmacy was invited to come (to BPOM office) to have the briefing (about dispensing antibiotics). However, it remains merely a briefing and direction without any strict supervision.”(Tech6)

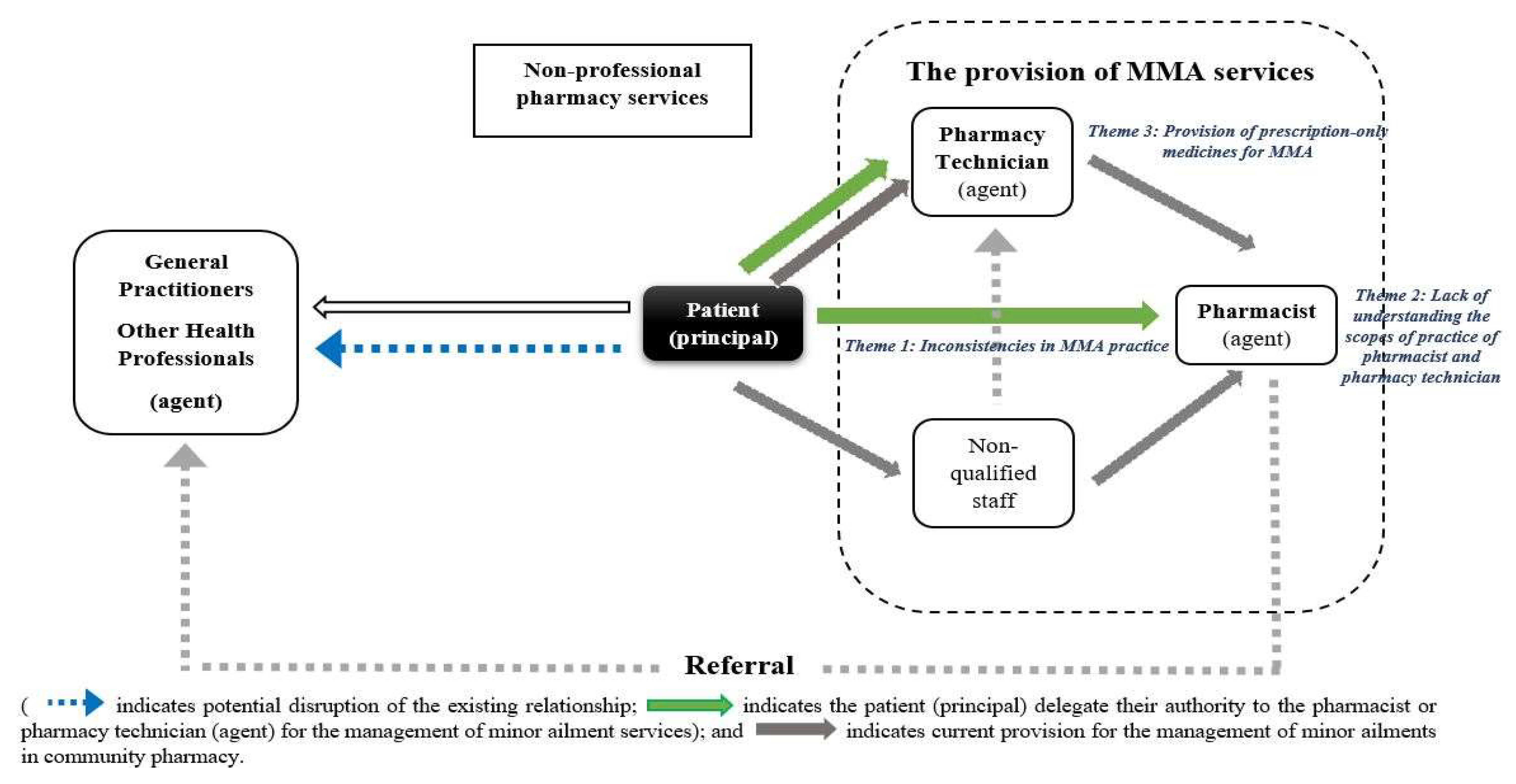

3.4. Agency Theory Application to the Provision of MMA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. COREQ Checklist—Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study

| No. Item | Guide Questions/Description | Reported on Page |

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||

| Personal Characteristics | ||

| 1. Inter viewer/facilitator | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? | (VM-investigator)—p.3 |

| 2. Credentials | What were the researcher’s credentials?, e.g., PhD, MD | MPharm—p.3 |

| 3. Occupation | What was their occupation at the time of the study? | a PhD student—p.3 |

| 4. Gender | Was the researcher male or female? | Female—p.3 |

| 5. Experience and training | What experience or training did the researcher have? | NVIVO training—p.4 |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| 6. Relationship established | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? | VM had not met the participants prior to the study start—p.3 |

| 7. Participant knowledge of the interviewer | What did the participants know about the researcher?, e.g., personal goals, reasons for doing the research | Participants knew VM reasons for doing the research as they were provided with brief information about the research prior to the interview—p.3 |

| 8. Interviewer characteristics | What characteristics were reported about the inter viewer/facilitator?, e.g., Bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic | Participants knew that VM was interested in the management of minor ailments in community pharmacies—p.3 |

| Domain 2: Study design | ||

| Theoretical framework | ||

| 9. Methodological orientation and Theory | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study?, e.g., grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis | Inductive thematic analysis—p.4 |

| Participant selection | ||

| 10. Sampling | How were participants selected?, e.g., purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball | Participants were recruited purposively—p.3 |

| 11. Method of approach | How were participants approached?, e.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email | Participants were recruited by phone—p.3 |

| 12. Sample size | How many participants were in the study? | 12 community pharmacists and 12 pharmacy technicians—p.6 |

| 13. Non-participation | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? | One pharmacist due to other commitments—p.6 |

| Setting | ||

| 14. Setting of data collection | Where was the data collected?, e.g., home, clinic, workplace | Data was collected online at either their home or workplace—p.3 |

| 15. Presence of non-participants | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? | No—p.3 |

| 16. Description of sample | What are the important characteristics of the sample?, e.g., demographic data, date | Age, gender, type of pharmacy, years of practice, average working hours, average MMA patients per week—p.4 |

| Data collection | ||

| 17. Interview guide | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? | Interview guide was not shared with the participants. The interview was pilot tested to two community pharmacists and two pharmacy technicians—p.4 |

| 18. Repeat interviews | Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? | No—p.4 |

| 19. Audio/visual recording | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? | Data were audio- and video-recorded—p.3 |

| 20. Field notes | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? | Yes—p.4 |

| 21. Duration | What was the duration of the inter views or focus group? | 45–60 min—p.3 |

| 22. Data saturation | Was data saturation discussed? | Yes—p.4 |

| 23. Transcripts returned | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? | No—p.4 |

| Domain 3: Analysis and findings | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| 24. Number of data coders | How many data coders coded the data? | One—p.4 |

| 25. Description of the coding tree | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? | No, However, coding was constantly refined—p.4 |

| 26. Derivation of themes | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? | Themes were derived from the data—p.4 |

| 27. Software | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? | NVivo (QSR NVivo version 20, QSR International)—p.4 |

| 28. Participant checking | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | No, However, one pharmacy academic (from Indonesian University) provided feedback on the final themes—p.4 |

| Reporting | ||

| 29. Quotations presented | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified?, e.g., participant number | Yes—p.9 |

| 30. Data and findings consistent | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | Yes—p.9 |

| 31. Clarity of major themes | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? | Yes—p.9 |

| 32. Clarity of minor themes | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? | Yes—p.9 |

Appendix B

- I have read the information sheet and had the nature of the study explained to me, and I agree to participate in the study described.

- I understand that the interview will be audio and video recorded. All my questions have been answered to my satisfaction.

- I understand that any personal information will be kept private and confidential. All data will be securely stored and will not be disclosed to any person other than a person authorised for the project.

- I understand that my participation in this study is voluntary and that I have the right to withdraw at any time.

- (1)

- Objective 1: To describe preparedness and factors influencing the delivery of minor ailments services

- Training and education:

- ○

- Tell me about your pharmacy education, including which university you went to?

- ○

- How did the university prepare you to deliver minor ailment services?

- ○

- How well do you consider the university prepared you to deliver minor ailment services?

- ○

- Do you think pharmacists are well prepared to manage minor ailments in the pharmacy? If yes, why? If no, why?

- ○

- Since you graduated from the university, what activities have you undertaken to ensure you are able to deliver minor ailments?

- ○

- Would you like to deliver a greater range of minor ailment services? If they answer YES, ask how could this occur? If they answer NO, ask do you feel that you are able to manage minor ailments complaint that coming to your pharmacy?

- Authority

- ○

- Do you know any legislations in Indonesia regarding pharmacist management of MMA?

- ○

- Are you aware of any limits that might restrict minor ailments that can be managed in community pharmacy in the Indonesian pharmacy services guidelines?

- (2)

- Objective 2: To investigate the scope of practice of pharmacists

- 3.

- Scope of practice (competence and accountability) of the pharmacists.

- ○

- What is the normal process when a customer comes into the pharmacy?

- ○

- Who would initially serve the costumers who come into the pharmacy?

- ○

- Have you been able to manage patients using the recent down-scheduled of medicines (Minister of Health Regulation No.3/2021)?

- (3)

- Objective 3: To explore the future practice of the MMA in community pharmacies in Central Java, Indonesia

- 4.

- Are you satisfied with the current practice of MMA? If they say YES, would you like to see any changes?

- 5.

- The impact of COVID-19 on the MMA

- Has the presence of COVID-19 changed your practice in relation to MMA?

- 6.

- Our project is about the scope of practice and factors influencing the preparedness of staff to deliver minor ailment services in community pharmacies in Central Java, Indonesia. Do you have further comments that come to mind that I have not asked about?

- (4)

- Objective 1: To describe preparedness and factors influencing the delivery of minor ailments services

- 7.

- Training and education:

- Tell me about your pharmacy education, including which university you went to?

- How did the university prepare you to deliver minor ailment services?

- How well do you consider the university prepared you to deliver minor ailment services?

- Do you think pharmacy technicians are well prepared to manage minor ailments in the pharmacy? If yes, why? If no, why?

- Since you graduated from the university, what activities have you undertaken to ensure you are able to deliver minor ailments?

- Would you like to deliver a greater range of minor ailment services? If they answer YES, ask how could this occur? If they answer NO, ask do you feel that you are able to manage minor ailments complaint that coming to your pharmacy?

- 8.

- Authority

- Do you know any legislations in Indonesia regarding pharmacy technician management of MMA?

- Are you aware of any limits that might restrict minor ailments that can be managed in community pharmacy in the Indonesian pharmacy services guidelines?

- (5)

- Objective 2: To investigate the scope of practice of pharmacy technicians

- 9.

- Scope of practice (competence and accountability) of the pharmacy technicians.

- What is the normal process when a customer comes into the pharmacy?

- Who would initially serve the costumers who come into the pharmacy?

- Have you been able to manage patients using the recent down-scheduled of medicines (Minister of Health Regulation No.3/2021)?

- (6)

- Objective 3: To explore the future practice of the MMA in community pharmacies in Central Java, Indonesia

- 10.

- Are you satisfied with the current practice of MMA? If they say YES, would you like to see any changes?

- 11.

- The impact of COVID-19 on the MMA

- Has the presence of COVID-19 changed your practice in relation to MMA?

- 12.

- Our project is about the scope of practice and factors influencing the preparedness of staff to deliver minor ailment services in community pharmacies in Central Java, Indonesia. Do you have further comments that come to mind that I have not asked about?

References

- University of Saskatchewan. Guidelines for Prescribing for Minor Ailments and Patient Self-Care. Available online: https://medsask.usask.ca/professional-practice/minor-ailment-guidelines.php (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Paudyal, V.; Hansford, D.; Cunningham, S.; Stewart, D. Over-the-counter prescribing and pharmacists’ adoption of new medicines: Diffusion of innovations. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013, 9, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwan, V.; Sabde, Y.D.; Byström, E.; De Costa, A. Treatment of pediatric diarrhea: A simulated client study at private pharmacies of Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2015, 9, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooling, K.L.; Kandeel, A.; Hicks, L.A.; El-Shoubary, W.; Fawzi, K.; Kandeel, Y.; Etman, A.; Lohiniva, A.L.; Talaat, M. Understanding antibiotic use in Minya District, Egypt: Physician and pharmacist prescribing and the factors influencing their practices. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhoseeny, T.A.; Ibrahem, S.Z.; Abo el Ela, A.M. Opinion of community pharmacists on use of nonprescription medications in Alexandria, Egypt. J. Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013, 88, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, A.R.; de Oliveira Sá, D.A.; Santos, A.P.; de Almeida Neto, A.; Lyra, D.P., Jr. Assessment of pharmacist’s recommendation of non-prescription medicines in Brazil: A simulated patient study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbo, P.U.; Aina, B.A.; Aderemi-Williams, R.I. Management of acute diarrhea in children by community pharmacists in Lagos, Nigeria. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 12, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Santos, A.P.; Mesquita, A.R.; Oliveira, K.S.; Lyra, D.P., Jr. Assessment of community pharmacists’ counselling skills on headache management by using the simulated patient approach: A pilot study. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 11, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showande, S.J.; Adelakun, A.R. Management of uncomplicated gastric ulcer in community pharmacy: A pseudo-patient study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmeier, K.C.; Desselle, S.P. Exploring the implementation of a novel optimizing care model in the community pharmacy setting. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Goodman, C. Performance of retail pharmacies in low- and middle-income Asian settings: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2016, 31, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, K.B.; Makhlouf, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.I. Community pharmacists’ management of minor ailments in developing countries: A systematic review of types, recommendations, information gathering and counseling practices. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, B.P.; Hassali, M.A.; Lim, C.J.; Saleem, F. Challenges in the management of community pharmacies in Malaysia. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferendina, I.; Wiryanto, W.; Harahap, U. Mapping of community pharmacy practices in Medan city Indonesia. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2021, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, A.P.; Wibowo, Y.; Setiawan, E.; Presley, B.; Mulyono, I.; Wardhani, A.S.; Sunderland, B. Evaluation of a community-based training to promote responsible self-medication in East Java, Indonesia. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitasari, H.P.; Faturrohmah, A.; Hermansyah, A. Do Indonesian community pharmacy workers respond to antibiotics requests appropriately? Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athiyah, U.; Setiawan, C.D.; Nugraheni, G.; Zairina, E.; Utami, W.; Hermansyah, A. Assessment of pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude and practice in chain community pharmacies towards their current function and performance in Indonesia. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermansyah, A.; Sukorini, A.I.; Setiawan, C.D.; Priyandani, Y. The conflicts between professional and non professional work of community pharmacists in Indonesia. Pharm. Pract. 2012, 10, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Siswati, S.; Cantika, M.; Faradila, A. Analysis of counselling services implementation by pharmacist at private pharmacies in Padang 2019. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Health Research (ISHR 2019), Bali, Indonesia, 28–30 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hoti, K.; Hughes, J.; Sunderland, B. Pharmacy clients’ attitudes to expanded pharmacist prescribing and the role of agency theory on involved stakeholders. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000, 320, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health. Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.J.; Susyanty, A.L. An analysis of pharmacy services by pharmacist in community pharmacy. Bul. Penelit. Sist. Kesehat. 2013, 15, 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rai Widowati, I.G.A.; Pradnyaparamita-Duarsa, D.; Putu-Januraga, P. Perceptions of the role of pharmacy assistants in providing patient counselling in community pharmacies in Indonesia. Med. Stud. /Stud. Med. 2021, 37, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiryanto; Harahap, U.; Karsono; Mawengkang, H. Community pharmacy practice standards as guidelines for pharmacists in performing profession in Indonesia. Int. J. Pharm. Teach. Pract. 2014, 5, 880–886. [Google Scholar]

- Antari, N.P.; Agustini, N.; Suena, N.M.D. The performance differences between high and low sales turnover community pharmacies. J. Adm. Kesehat. Indones. 2021, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashuri, Y.A.; Wulandari, L.P.L.; Khan, M.; Ferdiana, A.; Probandari, A.; Wibawa, T.; Batura, N.; Liverani, M.; Day, R.; Jan, S.; et al. The response to COVID-19 among drug retail outlets in Indonesia: A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2022, 22, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, G.; Ryan, M. Agency in health care: Getting beyond first principles. J. Health Econ. 1993, 12, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, D.A.; Schommer, J.C.; Doucette, W.R.; Kreling, D.H. Agency theory, drug formularies, and drug product selection: Implications for public policy. J. Public Policy Mark 1998, 17, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Vick, S. Patients, doctors and contracts: An application of principal-agent theory to the doctor-patient relationship. Scott. J. Polit. Econ. 1999, 46, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, M.A.; Mohaidin, Z. Models and theories of prescribing decisions: A review and suggested a new model. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.J.; Handayani, R.S. The preparedness of pharmacist in community setting to cope with globalization impact. J. Kefarmasian Indones. 2015, 5, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansyah, A.; Pitaloka, D.; Sainsbury, E.; Krass, I. Prioritising recommendations to advance community pharmacy practice. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitasari, H.P.; Aslani, P.; Krass, I. Challenges in the management of chronic noncommunicable diseases by Indonesian community pharmacists. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 13, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indonesia Health Minister. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor: 889/MENKES/PER/V/2011 Tentang Registrasi, Izin Praktik, Dan Izin Kerja Tenaga Kefarmasian [Minister of Health Regulations No. 889/MENKES/PER/V/2011 on Registration, Practice License, and Pharmacist Work License]; Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/139675/permenkes-no-889menkesperv2011-tahun-2011 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Mizranita, V.; Sim, T.F.; Sunderland, B.; Parsons, R.; Hughes, J.D. The Pharmacists’ and pharmacy technicians’ scopes of practice in the management of minor ailments at community pharmacies in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, T.N.; Van Amburgh, J.A.; Miller, D.M. In the midst of curricular revision, remember the importance of over-the-counter and self-care education. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2020, 12, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindel, T.J.; Yuksel, N.; Breault, R.; Daniels, J.; Varnhagen, S.; Hughes, C.A. Perceptions of pharmacists’ roles in the era of expanding scopes of practice. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm 2017, 13, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, M.L.; Hubball, H.T. Curricular integration in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizranita, V.; Sunderland, B.; Hughes, J.D.; Sim, T.F. The Management and Status of Minor Ailments in Community Pharmacies in Central Indonesia: A Mixed Methods Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mossialos, E.; Courtin, E.; Naci, H.; Benrimoj, S.; Bouvy, M.; Farris, K.; Noyce, P.; Sketris, I. From “retailers” to health care providers: Transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy 2015, 119, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelavanich, D.; Adjimatera, N.; Broese Van Groenou, L.; Anantachoti, P. Prescription and non-prescription drug classification systems across countries: Lessons learned for Thailand. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2753–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.M.; Byrkit, M.; Pham, H.V.; Pham, T.; Nguyen, C.T. Improving pharmacy staff knowledge and practice on childhood diarrhea management in Vietnam: Are educational interventions effective? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, A.H.M.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Hassali, M.A. Do professional practices among Malaysian private healthcare providers differ? a comparative study using simulated patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 2912–2916. [Google Scholar]

- Neoh, C.F.; Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Awaisu, A. Nature and adequacy of information on dispensed medications delivered to patients in community pharmacies: A pilot study from Penang, Malaysia. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 2, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112642/9789241564748_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 November 2022).

| Code | Gender | Age | Years of Practice | Pharmacy Type | Position | Average Working Hours Per Week | Average Consumers Per Week | Average MMA Patients Per Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharm1 | Female | 31–40 | 11–15 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 51+ | 251–350 | >70 |

| Pharm2 | Female | 31–40 | <2 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 51+ | 451–550 | >70 |

| Pharm3 | Female | 21–30 | <2 | Co-located with a medical centre * | Additional pharmacist | 41–50 | >700 | 61–70 |

| Pharm4 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 51+ | 351–450 | >70 |

| Pharm5 | Male | 21–30 | <2 | Franchise | Pharmacy manager | 41–50 | >700 | >70 |

| Pharm6 | Male | 41–50 | >15 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 41–50 | 551–700 | >70 |

| Pharm7 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Franchise | Pharmacy manager | 31–40 | 100–150 | 61–70 |

| Pharm8 | Female | 31–40 | 11–15 | Independent | Pharmacy manager | 41–50 | <100 | 61–70 |

| Pharm9 | Female | 41–50 | 6–10 | Independent | Pharmacy manager | 31–40 | 351–450 | 21–30 |

| Pharm10 | Female | 31–40 | 6–10 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 41–50 | 151–250 | 41–50 |

| Pharm11 | Female | 21–30 | <2 | Co-located with a doctor’s practice * | Additional pharmacist | 51+ | 551–700 | 21–30 |

| Pharm12 | Male | 31–40 | 6–10 | Independent | Pharmacy manager and owner | 41–50 | 151–250 | 41–50 |

| Code | Gender | Age | Years of Practice | Pharmacy Type | Pharmacy Ownership | Average Working Hours Per Week | Average Consumers Per Week | Average MMA Patients Per Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tech1 | Male | 21–30 | 2–5 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | 451–550 | >70 |

| Tech2 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Franchise | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | >700 | >70 |

| Tech3 | Female | 21–30 | 6–10 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 21–30 | 251–350 | >70 |

| Tech4 | Female | 21–30 | <2 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 51+ | 151–250 | >70 |

| Tech5 | Female | 21–30 | 6–10 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | 151–250 | 31–40 |

| Tech6 | Female | 41–50 | >15 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 21–30 | 451–550 | >70 |

| Tech7 | Male | 21–30 | 2–5 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | 451–550 | >70 |

| Tech8 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Franchise | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | >700 | >70 |

| Tech9 | Female | 21–30 | <2 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | 551–700 | >70 |

| Tech10 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Franchise | State-owned enterprise | 41–50 | 451–550 | >70 |

| Tech11 | Female | 21–30 | 2–5 | Independent | Non-pharmacist | 41–50 | >700 | >70 |

| Tech12 | Female | 31–40 | >15 | Co-located with a medical centre * | Regional-owned enterprises | 41–50 | >700 | >70 |

| Key Theme | Theme | Sub-Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Perspectives of the current MMA practice | Inconsistencies in MMA practice |

|

| Lack of understanding the scopes of practice of pharmacist and pharmacy technician |

| |

| Provision of prescription-only medicines for MMA |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mizranita, V.; Hughes, J.D.; Sunderland, B.; Sim, T.F. Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians’ Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050132

Mizranita V, Hughes JD, Sunderland B, Sim TF. Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians’ Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study. Pharmacy. 2023; 11(5):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050132

Chicago/Turabian StyleMizranita, Vinci, Jeffery David Hughes, Bruce Sunderland, and Tin Fei Sim. 2023. "Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians’ Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study" Pharmacy 11, no. 5: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050132

APA StyleMizranita, V., Hughes, J. D., Sunderland, B., & Sim, T. F. (2023). Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians’ Perceptions of Scopes of Practice Employing Agency Theory in the Management of Minor Ailments in Central Indonesian Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study. Pharmacy, 11(5), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050132