Discordance in Addressing Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities: Patient and Provider Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Study Design

2.2. Site

2.3. Participants

- Fort HealthCare Providers (FP)—includes FHC providers from multiple specialties who were engaged volunteers on the FHC Opioid Taskforce and invested in addressing the opioid crisis.

- Patients with lived experience with opioids (PT)—includes patients who were actively managing chronic pain with prescription opioids and patients who were recovering from prescription opioid addiction.

- Community Stakeholder (CS)—includes members from the community who have strong relationships with FHC leadership and are involved in managing the opioid crisis such as county sheriff, a school district nurse, a community advocate/city council member, independent community pharmacists, public health officials, and patient advocacy group leaders.

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Interviews

2.7. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Setting

3.2. Summary of Findings

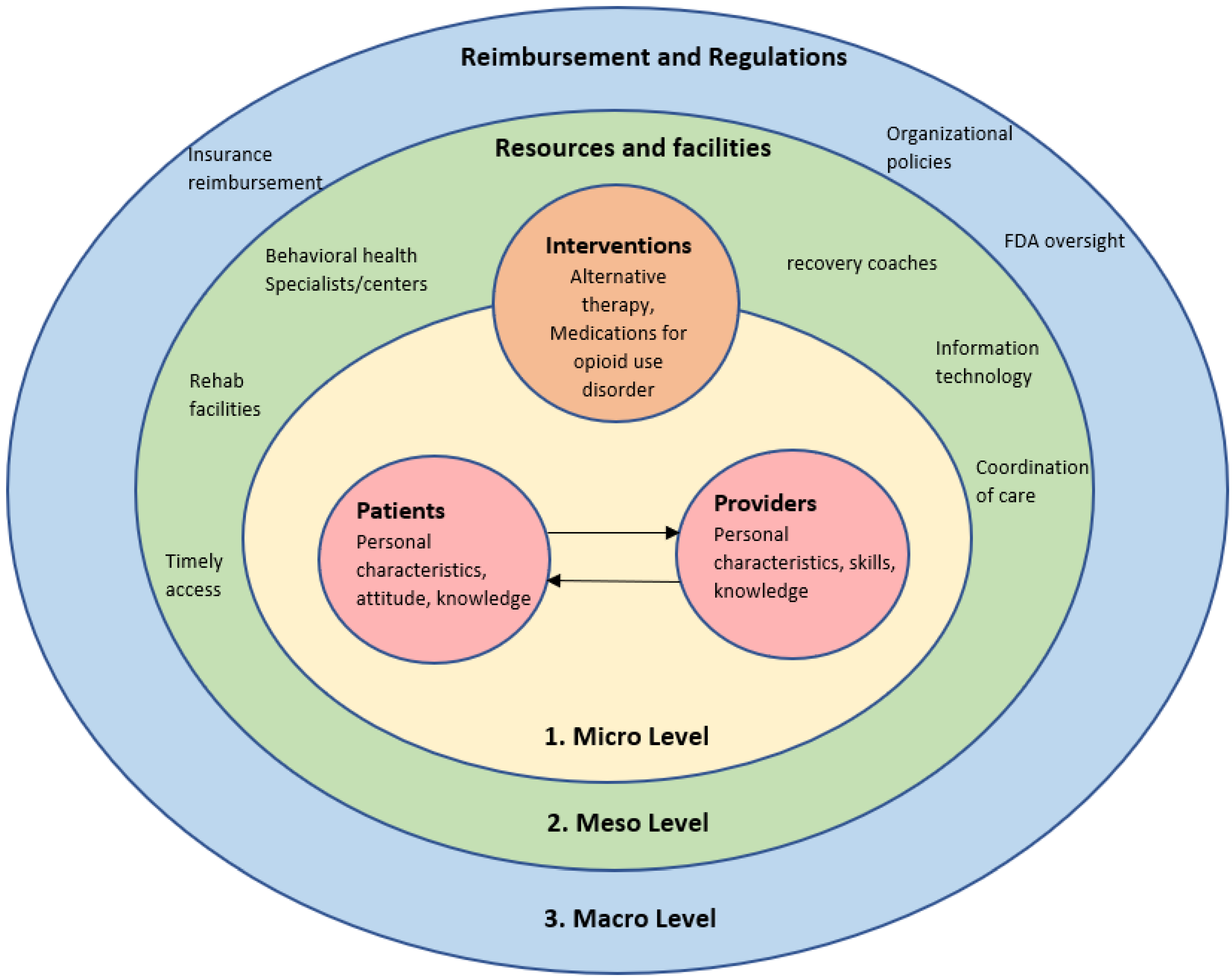

3.2.1. Microlevel: The Interaction between Patient and Providers

- Providers’ knowledge, attitude, and professional skills

- b.

- Patient characteristics and responsibilities

- c.

- Patient-provider communication about treatment goals and tapering

- d.

- Interventions

3.2.2. Mesolevel: Resources and Facilities

- Process of Care

- b.

- Infrastructure

3.2.3. Macrolevel: Structural, Financial, and Legal Conditions of Care Provision

- Financing and reimbursement

- b.

- Policies, laws, and regulations

4. Discussion

4.1. Microlevel: The Interaction between Patient and Providers

4.2. Meso- and Macrolevel of Care

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chronic Pain Management and Opioid Misuse: A Public Health Concern (Position Paper). Available online: https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/chronic-pain-management-opiod-misuse.html (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ahmad, F.B.; Rossen, L.M.; Sutton, P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2021; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Li, M.; Florence, C. State-Level Economic Costs of Opioid Use Disorder and Fatal Opioid Overdose—United States, 2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, R.; Derry, S.; Taylor, R.S.; Straube, S.; Phillips, C.J. The costs and consequences of adequately managed chronic non-cancer pain and chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. Off. J. World Inst. Pain 2014, 14, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, O.; McGuire, B.E.; Finn, D.P. The effect of pain on cognitive function: A review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 93, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mack, K.A.; Jones, C.M.; Ballesteros, M.F. Illicit Drug Use, Illicit Drug Use Disorders, and Drug Overdose Deaths in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas—United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 3241–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Preventing and Treating Harms of the Opioid Crisis: An Assessment to Identify Geographic Gaps in Services and a Plan to Address These Gaps. Available online: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02605.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Rural Voices for Prosperity: A Report of the Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Rural Prosperity. Available online: Web_Governors-Blue-Ribbon-Commission-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Keyes, K.M.; Cerdá, M.; Brady, J.E.; Havens, J.R.; Galea, S. Understanding the Rural-Urban Differences in Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and Abuse in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e52–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, B.; Dhanani, L.Y.; Miller, W.C. Rural-Urban Differences in Physician Bias toward Patients with Opioid Use Disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Boekel, L.C.; Brouwers, E.P.; van Weeghel, J.; Garretsen, H.F. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 131, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, S.C.; Molloy, E.; Keating, J.L. Stigma Experienced by People with Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Ruddere, L.; Goubert, L.; Stevens, M.; de Williams, A.C.C.; Crombez, G. Discounting pain in the absence of medical evidence is explained by negative evaluation of the patient. Pain 2013, 154, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergman, A.A.; Matthias, M.S.; Coffing, J.M.; Krebs, E.E. Contrasting tensions between patients and PCPs in chronic pain management: A qualitative study. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, E.A.; De Weert-Van Oene, G.H.; Sensky, T.; Van Der Staak, C.P.; De Jong, C.A. Treatment goals in addiction healthcare: The perspectives of patients and clinicians. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 57, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Sales, C.; Ashworth, M. Does outcome measurement of treatment for substance use disorder reflect the personal concerns of patients? A scoping review of measures recommended in Europe. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 179, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, M.; Brown, J.B.; Donner, A.; McWhinney, I.R.; Oates, J.; Weston, W.W.; Jordan, J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J. Fam. Pract. 2000, 49, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fiscella, K.; Meldrum, S.; Franks, P.; Shields, C.G.; Duberstein, P.; McDaniel, S.H.; Epstein, R.M.J.M.C. Patient trust: Is it related to patient-centered behavior of primary care physicians? Med. Care 2004, 42, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinuzzi, C. The Methodology of Participatory Design. Tech. Commun. 2005, 52, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, A.C.; Commanda, L.E.; Freeman, W.L.; Gibson, N.; McCabe, M.L.; Robbins, C.M.; Twohig, P.L. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. BMJ 1999, 319, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chui, M.A.; Stone, J.A.; Holden, R.J. Improving over-the-counter medication safety for older adults: A study protocol for a demonstration and dissemination study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2017, 13, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisconsin Network for Research Support. Available online: https://winrs.nursing.wisc.edu/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; p. xiii 312. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vennedey, V.; Hower, K.I.; Hillen, H.; Ansmann, L.; Kuntz, L.; Stock, S. Patients’ perspectives of facilitators and barriers to patient-centred care: Insights from qualitative patient interviews. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear, K.; Haass-Koffler, C.L.; Chavanne, D. Opioid use and stigma: The role of gender, language and precipitating events. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 185, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.; Bhalerao, A.; Bawor, M.; Bhatt, M.; Dennis, B.; Mouravska, N.; Zielinski, L.; Samaan, Z. “Don’t Judge a Book Its Cover”: A Qualitative Study of Methadone Patients’ Experiences of Stigma. Subst. Abus. Res. Treat. 2017, 11, 1178221816685087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezell, J.M.; Walters, S.; Friedman, S.R.; Bolinski, R.; Jenkins, W.D.; Schneider, J.; Link, B.; Pho, M.T. Stigmatize the use, not the user? Attitudes on opioid use, drug injection, treatment, and overdose prevention in rural communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.M.; Kennedy-Hendricks, A.; Barry, C.L.; Bachhuber, M.A.; McGinty, E.E. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 221, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, D.; Giannetti, V.; Kamal, K.M.; Covvey, J.R.; Tomko, J.R. The relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and practices of community pharmacists regarding persons with substance use disorders. Subst. Abus. 2021, 42, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tools for Stakeholder Engagement in Research. Available online: https://www.hipxchange.org/StakeholderEngagementTools (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Goddu, A.P.; O’Conor, K.J.; Lanzkron, S.; Saheed, M.O.; Saha, S.; Peek, M.E.; Haywood, C.; Beach, M.C. Do Words Matter? Stigmatizing Language and the Transmission of Bias in the Medical Record. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weimer, M.B.; Wakeman, S.E.; Saitz, R. Removing One Barrier to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: Is It Enough? J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 325, 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy-Hendricks, A.; Barry, C.L.; Stone, E.; Bachhuber, M.A.; McGinty, E.E. Comparing perspectives on medication treatment for opioid use disorder between national samples of primary care trainee physicians and attending physicians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020, 216, 108217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, R.R.; Smith, T.B. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swift, J.K.; Callahan, J.L. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.W.; Levy, C.; Matlock, D.D.; Calcaterra, S.L.; Mueller, S.R.; Koester, S.; Binswanger, I.A. Patients’ Perspectives on Tapering of Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthias, M.S. Opioid Tapering and the Patient-Provider Relationship. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davis, M.P.; Digwood, G.; Mehta, Z.; McPherson, M.L. Tapering opioids: A comprehensive qualitative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 586–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissin, W.; McLeod, C.; Sonnefeld, J.; Stanton, A. Experiences of a national sample of qualified addiction specialists who have and have not prescribed buprenorphine for opioid dependence. J. Addict. Dis. 2006, 25, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, E.; Catlin, M.; Andrilla, C.H.A.; Baldwin, L.-M.; Rosenblatt, R.A. Barriers to Primary Care Physicians Prescribing Buprenorphine. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madden, E.F. Intervention stigma: How medication-assisted treatment marginalizes patients and providers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 232, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.P.; Fullerton, C.A.; Kim, M.; Montejano, L.; Lyman, D.R.; Dougherty, R.H.; Daniels, A.S.; Ghose, S.S.; Delphin-Rittmon, M.E. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarvis, B.P.; Holtyn, A.F.; Subramaniam, S.; Tompkins, D.A.; Oga, E.A.; Bigelow, G.E.; Silverman, K. Extended-release injectable naltrexone for opioid use disorder: A systematic review. Addiction 2018, 113, 1188–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaromy, M.; Duhigg, D.; Metcalf, A.; Carlson, C.; Kalishman, S.; Hayes, L.; Burke, T.; Thornton, K.; Arora, S. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): A new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst. Abus. 2016, 37, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QuickFacts: Wisconsin. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/WI (accessed on 17 November 2021).

| Aspects of Each Level of Care | Group | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Providers’ knowledge, attitude, and professional skills | Patients | “And I remember saying to the doctor, Dr. [NAME], he’s going to get addicted, because he had him on like five different pain meds. And Dr. [NAME] said, on, don’t worry, this, in a little, we will get him off.” Patient 6 “The man literally took two steps back from me, like I had leprosy. And the first sentence out of his mouth was, I am not giving you any pills.” Patient 3 “They can believe a broken arm, a broken leg, wisdom teeth, whatever. They can believe in that. But chronic pain is something new to a lot of people.” Patient 2 “And to their credit, addicts are, we’re liars, we’re cheats, we’re thieves.” Patient 3 |

| Providers | “I’m going back to your chart and so I went back like five years before I found out that she hurt her back weeding her garden, and someone started her out on Tylenol-Codeine then they just kept increasing the dose.” Physician assistant Written on sticky note: How to handle patient who never seems able to get drug screen done or pill count done; get mixed message about discharge of patient (for failure of contract) vs. we do not want to lose patient from clinic | |

| Patients’ knowledge, attitude, and personal characteristics | Patients | “And I don’t want to be on opioids. But I don’t want to feel the results of being off of it either.” Patient 4 “We all have assumptions of whatever. But we need to be looked at as human beings, mind, body, and soul.” Patient 3 |

| Providers | “Yeah, well, “why can’t I have more ?” and then explain why we can’t have more and then they seem to understand that but they also don’t seem to understand that if you have too much, that can make the pain worse and if we back down, it might be worse for a couple of weeks but then it might actually be better it’s like they’re too afraid to try that.” Pharmacist 1 “What I’ve been finding it’s like how do I break through these roadblocks to get people to see that maybe there is a benefit” Pharmacist 1 | |

| Patient-provider communication | Patients | “Doctors kind of, do it this way, and this is the way they say it should be done, when it really should and that’s where people tend to drop off and fall off here and there in the system, because that particular way is just not working for them.” Patient 5 |

| Providers | “ I think maybe our doctors aren’t really having that conversation with the patient. They keep saying, I would like you to go down I’m not going to fill more for you.” Pharmacist 1 “and she said, like the relationship she had with her previous providers, they just kind of come in, refill them and be like okay they’re working fine and then go.” Pain management practitioner “postoperative pain management is important. You know, new people come in, being put on narcotics. If we could, you know, there are people who are going to need them, without a doubt. But if you set expectations, we set the timeframe right, that we set everybody straight so that we prevent those people from progressing into addiction.” Hospitalist | |

| Medication for opioid use disorder | Patients | “I think Suboxone can be a great treatment, but it’s not, they’re not using it as, I believe, that you’re supposed to. You know, it’s supposed to be a gateway to get off them, but they become long term. My son has been on it for seven years.” Patient 4 “and he went in to the hospital to get off the Suboxone because he didn’t want to be in that spot any longer. It was too easy to abuse. And that’s what he was doing. So I actually just talked to him today, and he’s doing really good. He’s off it completely. But we’ve talked a lot about how coming off of Suboxone was harder for him than coming off heroin.” Patient 6 “And something I wrote down is I personally believe that Suboxone should be more available. Just speaking of me trying to get off heroin starting in like 2012, I think. It was so hard to find a provider.” Patient 3 |

| Providers | Written on sticky note: “Surgical patients on methadone therapy: how to manage pre-surgery, intra surgery and post survey, how to warn anesthesia team.” | |

| Communication among staff and Coordination of care | Patients | “The ER never called pain management. I almost lost my prescription because they had given me more than what I was allowed to try to get me back down to the pain level.” Patient 2 |

| Providers | “so we just told the patient, you know, we don’t know but we see that you’ve been getting scripts from your primary so like we are not touching that because we don’t want to step on anybody’s toes. Turns out the primary did want us.” Pain management nurse | |

| Timely access | Patients | “So now I’m down to two pills a day instead of four. But that’s not working for me. Can I try three? But it might take the provider a week to get back to me, right?” Patient 1 “And I’ll tell you for myself, being an addict, you give me more than 12 h, I’m going back… so the fact that, you know, you give them some hope, but then, well, they have a bed, but it won’t be available until such and such.” Patient 4 |

| Providers | NA | |

| Alternative therapy issues | Patients | “Physical therapy doesn’t do anything. It just, it makes it just flare up and that. So I have radiofrequency coming up in September because that’s, that’s not for my bulge. That’s for my arthritis that I have on four disks I’m having for that. But my bulge, I had a cortisone shot done. That didn’t do nothing for it.” Patient 2 |

| Providers | “We have really good physical therapy department. Yeah, they do more than just exercises. They have all kinds of modalities they, they’re very, very good. Again, if people would go in there open minded. Most of them actually get help.” Physician assistant | |

| Behavioral health and recovery resources | Patients | “And my other issue with [……] County in general, so gigantic, a lack of mental healthcare services. I currently see a psychiatrist and therapist at [……] County Human Services. They are swamped. We need more facilities.” Patient 3 |

| Providers | “I think, as an organization, we need to do a better job of recruiting for behavioral health professionals. And I get that it’s hard. It’s a hot area right now.” Pharmacist 1 | |

| Information technology | Patients | “It’s on your record, and it doesn’t matter if you’ve been clean for ten years. It shows up on your record, and pain management is all nice, nice, nice, until they scroll further down and read your, and see that it happened in the past, ten years ago. And says, oh, I’m not giving you any pills.” Patient 3 |

| Providers | “I’ll just add on the PDMP, I think this is an immensely powerful tool that is underutilized. And part of that is not due to anybody’s fault. It’s due to our inability to integrate it with the EHR. So you got this immensely powerful tool that is clunky to use.” Pharmacist 2 | |

| Financing and reimbursement | Patients | “The insurance companies, they make you go through loophole after loophole after loophole… you got to go through ten different things before the insurance company finally says, hey, why don’t we give that, do that procedure for that person to begin with? Patient 2 |

| Providers | “like we build them up and say, oh, drugs aren’t everything, drugs aren’t everything. And then they’re, we say, oh, we changed our minds. Since it won’t be covered by insurance, drugs are everything.” Pharmacist 1 | |

| Policies, laws, and regulations | Patients | NA |

| Providers | “[Pharmacy name] told me if an MME is over 50, they will not dispense it, period.” Pharmacist 1 “Can I add one thing on the expectation that I think works against us sometimes is we are measured on patient satisfaction based on pain control. And I think, in a lot of aspects, that works against us when you’re trying to set good expectations. There’s a question on the patient survey, did we control their pain, or something to that effect.” Pharmacist 2 “I think that if the FDA start sending out letters like they have been. That might be a wakeup call for, some providers, right, because they will be like Oh my god! they’re watching! Because they are like, outside the realm of what’s considered good practice.” Physician assistant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qudah, B.; Maurer, M.A.; Mott, D.A.; Chui, M.A. Discordance in Addressing Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities: Patient and Provider Perspectives. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040091

Qudah B, Maurer MA, Mott DA, Chui MA. Discordance in Addressing Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities: Patient and Provider Perspectives. Pharmacy. 2022; 10(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040091

Chicago/Turabian StyleQudah, Bonyan, Martha A. Maurer, David A. Mott, and Michelle A. Chui. 2022. "Discordance in Addressing Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities: Patient and Provider Perspectives" Pharmacy 10, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040091

APA StyleQudah, B., Maurer, M. A., Mott, D. A., & Chui, M. A. (2022). Discordance in Addressing Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities: Patient and Provider Perspectives. Pharmacy, 10(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040091