Exploring the Views of Healthcare Professionals Working in a Mental Health Trust on Pharmacists as Future Approved Clinicians

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Approved Clinicians

1.2. Mental Health Pharmacists

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Recruitment

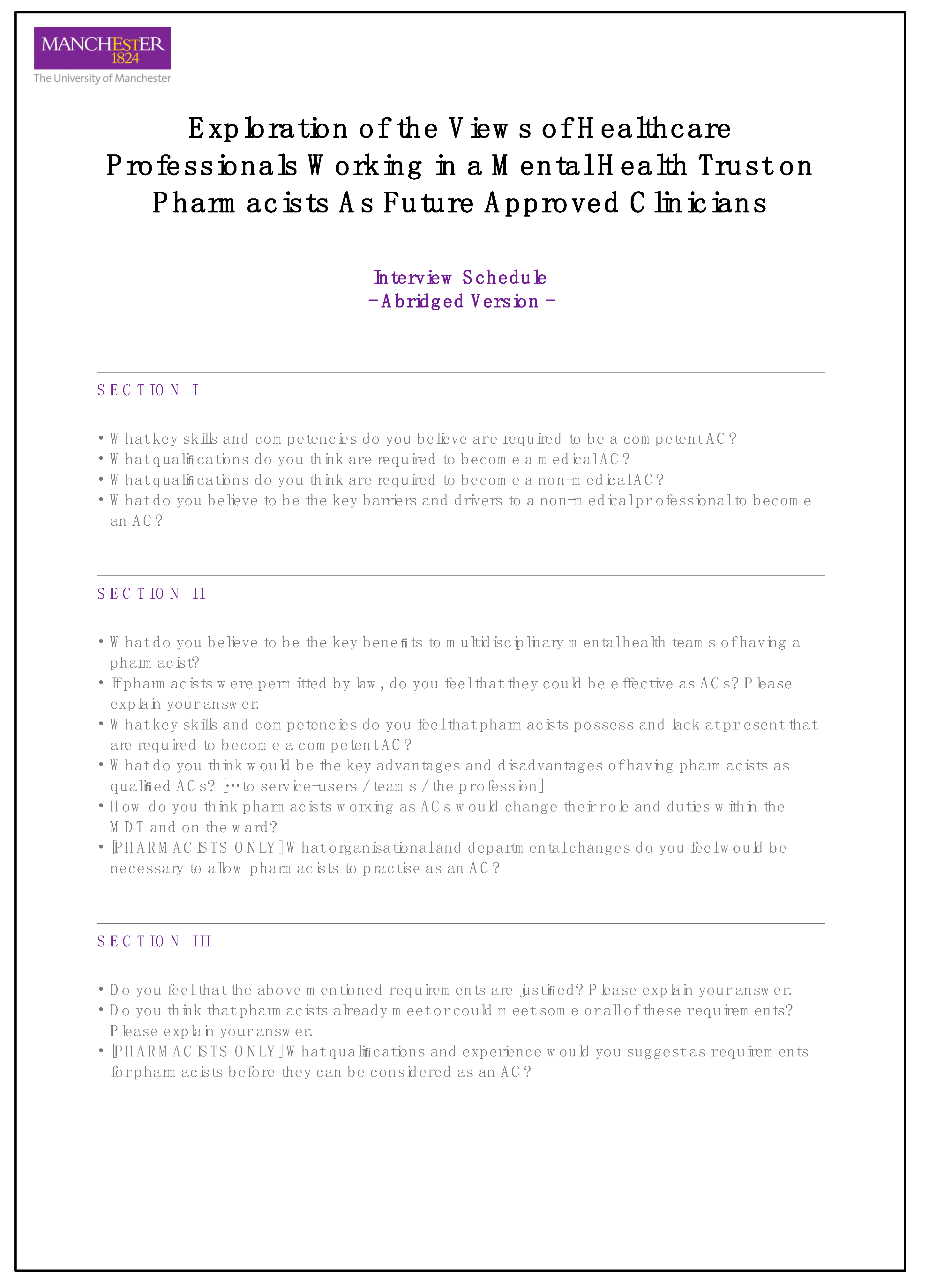

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Challenges Surrounding the Non-Medical AC Role

3.1.1. Barriers

“The traditional AC is a psychiatrist … and I imagine there may be some resistance, maybe from psychiatrists that don’t want, potentially, nurses or occupational therapists or anyone to be in that role”(Nurse 01)

3.1.2. Drivers

“I think professional autonomy and job satisfaction are probably the two biggest drivers for a lot of us, isn’t it?”(Psychiatrist 03)

“Our mental health services are traditionally structured with a consultant in the team generally taking the lead and being the lead for all the people under the care of that—either ward or community—team. So, increasing the scope for other professionals, actually, to allow a bit more for restructuring mental health services potentially.”(Pharmacist 05)

3.2. The Role and Benefits of Mental Health Pharmacists

“Well, you [pharmacists] are a font of all knowledge! You know more about drugs than me, you’ve got it off the top of your head more than me… You know the interactions, you know the monitoring requirements … You’ve got that knowledge and you know how to lay your hands on knowledge that I don’t. So, yes, it’s useful to have you in the team.”(Psychiatrist 01)

“I’m very much in favour of mental health pharmacists as part of MDTs, and particularly, in the inpatient setting. My opinion is that every MDT and every ward should have its own mental health pharmacist and, again, my opinion would be that ideally the mental health pharmacist should form part of every ward round … The ability to have a discussion between prescriber and pharmacist, I think, it really adds as a sum of a force multiplier, in terms of the effectiveness of the prescribing as well as increasing safety.”(Psychiatrist 02)

“Also, patients tend to be a lot more honest with us from what I’ve seen … patients might open up to a pharmacist because they don’t see us in the same way as they might see the consultant; that we are often seen as a problem-solvers rather than problem-makers by the patient.”(Pharmacist 03)

3.3. Skills and Competencies of Mental Health Pharmacists

“Pharmacists also have got a knowledge of the Mental Health Act, in terms of different sections and that kind of thing, which would apply very well to being an RC [or an AC].”(Psychiatrist 04)

“Assessing risks—and this is something that if you have not had experience with this, it may be difficult to master in a short period of time. It requires seeing many cases, following them up, seeing what happened with them… to understand why, when we say this person is at risk of harming themselves, why we say that. And it’s not just about doing a one-off assessment.”(Psychiatrist 05)

“I don’t think we have the skills in—I think—diagnosis … I’d be inclined to say that given that doctors go through—is it six years specialist training to become a psychiatrist?—I am not sure that this is something that pharmacist should or could be doing, actually.”(Pharmacist 01)

“So, what I’m saying is if psychologists can do it—they won’t have had a vast amount of training in their undergraduate qualification on diagnosis—because they are more into therapeutic interventions—and that’s probably the same for pharmacists—so there is a bit of a gap but they’re all in the same place, aren’t they… Nurses—well, they won’t have been used to making diagnoses … and they’ve had to learn that on their job through experience—so, none of these things are insurmountable.”(Pharmacist 05)

“On the negative side, I don’t think pharmacists interact with patients one-to-one as much as doctors, nurses or psychologists do … For me, what is lacking is that sort of patient contact; a diagnostic curiosity.”(Psychiatrist 03)

“It’s important that pharmacists are part of a team—but, of course, if they are stretched and have to visit five more wards then they’re not able to be part of the team … And this does limit their ability.”(Psychiatrist 03)

3.4. Pharmacists and ACs—Bridging the Gap

“Get them more involved in the care planning and in the assessment process… so, maybe there can be a role that is created that incorporates both and then they could build upon that pathway for the approved clinician bit.”(Nurse 01)

“I guess, department-wise, you would have to have a dedicated pharmacist part of the ward.”(Pharmacist 05)

“I think they [pharmacists] would [have to] be a lot more integrated into a team; they would probably have a bit of responsibility of managing other people and they would certainly have a clinical leadership role within the team and they would clinically be leading a multidisciplinary team.”(Pharmacist 06)

“There may well be things like credentialing or more advanced practice—so whether through a formal process or through using or reflecting on things like the advanced pharmacy practice framework, or the multi professional advanced clinical practitioner framework, or the College of Mental Health Pharmacy credentialing—this, sort of, almost helps assure people that you do practise at a certain level; and it would help assure you, I think, as well.”(Pharmacist 05)

“I think pharmacists meet many of the requirements for being responsible clinician as it is… but they would have to have a job that is set up for development - where people are going to have to spend maybe two years on getting clinical cases, and also maybe do a kind of an exam on top of some kind of a Masters of Psychiatry or similar plus clinical cases—a portfolio of cases, and that kind of thing. So, it’s doable but it would need to be organised.”(Psychiatrist 04)

4. Discussion

4.1. Statement of Key Findings

4.2. Strengths and Weaknesses

4.3. Interpretation

4.4. Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| BARRIERS—INTERNAL | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Description with Participant Quote |

| 1 Commitment | One explanation by a large number of the participants for the relative lack of practising non-medical ACs was that albeit adequately skilled and experienced, many individuals would likely be put off by the amount of work required to eventually qualify as ACs via the portfolio route. What is more, many believed that once one had embarked on this training pathway, there was seldom sufficient continuing support from organisations—for instance, protected time for learning—which meant that a great proportion would eventually completely abandon their training. “You know, it’s very hard work to get there—I think most people will drop at the first or second hurdle. Because you’ve got your own job to do, so how are you going to find the time to skill yourself up with all this stuff you need?” (Psychiatrist 01) |

| 2 Renumeration | Participants shared doubts about the standardisation of the pay structure for newly qualified non-medical ACs. Many showed concerns that due to the perceived lack of qualified non-medical ACs, each organisation might choose to approach remuneration differently and they also expressed scepticism about there being a consistent and fair strategy across the board with regards to pay progression down the line. “Is there a clear pathway to it [practising as a non-medical AC]? And if there is, is there any extra reward as well as responsibility? So, is it associated with a higher banding, and all of that.” (Pharmacist 06) |

| 3 Responsibility and Accountability | Participants reported that many professionals considering training to be an AC might be demoralised by the amount of responsibility and accountability associated with the role. Furthermore, several participants had doubts about the provision of appropriate and sufficient indemnity by employing trusts. “This is a big thing; you have got a lot of power and influence if you’re the AC, for someone you can make decisions on their behalf, so, this is something that could be quite scary for a lot of people.” (Pharmacist 03) |

| 4 Therapeutic Relationship | Participants felt that a number of non-medical professionals working in mental health greatly valued the therapeutic relationship they established with service users. Some, therefore, feared that, by assuming the role of the AC—which includes having to apply coercive powers under the MHA—one would have to sacrifice this highly rewarding aspect of their day-to-day job. “I see it as, kind of, a barrier, thinking, why would I want to be [the responsible clinician]—let’s leave the detention to somebody else and I’m the one who does the therapeutic interventions.” (Pharmacist 06) |

| 5 Additional Jobs | Many expressed the suspicion that even after qualifying as an AC professionals might still be required to carry on working in their current substantive role for a period of time due to the assumption that there might be a greater demand for a job role that is established and widely recognised in the system—one that could be deemed by employers to be too valuable to lose—compared with one that they would likely be unfamiliar with. “So, I suspect once someone qualifies and wants to practise as an AC or an RC they would keep their current role and responsibilities and they would add the extras on to that—that’s how things work within the NHS!” (Pharmacist 01) |

| 6 Inferiority | Some participants stated that despite the fact that some non-medical ACs might also act as non-medical prescribers, some might not possess the experience and expertise to be able to prescribe completely independently, and thus might risk being regarded as inferior compared to their medical counterparts. Some felt that this was one of the fundamental issues with the non-medical AC role, too. “Certainly, I have had that with prescribing: some people don’t believe that nurses should be prescribers, and I think there is probably an element of that with ACs as well.” (Nurse 01) |

| BARRIERS—EXTERNAL | |

| Theme | Description with Participant Quote |

| 1 Awareness | Some participants stated that the concept of the non-medical AC had never truly materialised and thus the role was not frequently spoken of by organisations. They argued that as the non-medical AC role was less known amongst potential candidates, it meant that very few would even consider it as a route of career progression and organisations were also unlikely to be able to provide much information to anyone even wishing to find out more about the role. “The barrier is the story around it, and the communication around it … I suppose the whole framework around it is kind of not clear to me; and there is always advertising around, you know, “Do this non-medical prescribing course or the advanced practitioner role!”, but the publicity around responsible clinician is quite small.” (Pharmacist 06) |

| 2 Training Gap | Several participants stated that unlike their medical counterparts non-medical ACs did not have a clear training pathway and that they were only able to qualify via the portfolio route. They explained that this route was a lengthy process during which the employing trust was often required to support trainees by providing additional protected time whilst also needing to manage the competing operational demands of the service. Many indicated that without a dedicated training pathway the uptake of the non-medical AC role would be unlikely to change. “I think perhaps barriers would be in terms of knowledge. There is doctrine—there is a fairly established path for psychiatrists that they’re expected to progress in order to become ACs. Whilst not absolutely compulsory, it is seen as the norm; it is very commonly done as a clear established path … My perception is that for non-medical ACs those well-trodden pathways, as it were, don’t exist; there is perhaps not such a well-defined path or at least one where a non-medic that is becoming an AC is perhaps less likely to have other colleagues who’ve been along that route to help them along that path—it may be less established.” (Psychiatrist 02) |

| 3 Status Quo | Several participants reflected that prior to the 2007 amendment only medical doctors were in possession of the AC powers under the Mental Health Act. Some believed that despite the change in law, there was still a need for a substantial shift in the culture and system of mental health provision in England and Wales, adding that there might still remain resistance—by colleagues and service users alike—toward fully accepting non-medical professionals as ACs. “I don’t understand why a pharmacist or anybody else would want to be an AC unless we all change our mindset as to what an AC is … I think it’s too big a leap for 2020.” (Psychiatrist 01) |

| 4 Impracticalities | Many argued that an important reason for the poor uptake of the non-medical AC role was that non-medical professionals were not able to completely replace medical ACs due to fundamental differences in their skills as well as in some of the powers they could wield under the MHA. They reasoned that this rendered the non-medical AC role highly impractical. “If you could have an RC who is a non-medic, you would have to have an AC—a medic—working with you. Because, for instance, a psychologist working as an RC may not know much about medications or can’t prescribe, and they will still need someone to prescribe. So, then they would have an AC who is a medical doctor working with them. Now, I’m not sure there are many ACs who would want to do that role. Because they’ll say ‘If I’m going to do this, I might as well be the RC.’” (Psychiatrist 03) |

References

- Department of Health. New Ways of Working for Everyone. A Best Practice Implementation Guide. 2007. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105064321/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_079106.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Barcham, C. Understanding The Mental Health Act Changes—Challenges And Opportunities For Doctors. BJMP 2008, 1, 13–17. Available online: https://www.bjmp.org/content/understanding-mental-health-act-changes-challenges-and-opportunities-doctors (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Laing, J. The Mental Health Act: Exploring the role of nurses. Br. J. Nurs. 2012, 21, 234; discussion 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oates, J.; Brandon, T.; Burrell, C.; Ebrahim, S.; Taylor, J.; Veitch, P. Non-medical approved clinicians: Results of a first national survey in England and Wales. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2018, 60, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, S. Multi-professional approved clinicians’ contribution to clinical leadership. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2017, 13, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, L. Prescribing rights for pharmacists in Australia-are we getting any closer? Pharmacist 2008, 27, 624–629. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43496984_Prescribing_Rights_for_pharmacists_in_Australia_-_are_we_getting_any_closer (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Bissell, P.; Traulsen, J.M. Sociology and Pharmacy Practice; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Healthcare and Excellence. Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. 2015. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Department of Health. Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines (the Crown Report). 1999. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4077153.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Turner, E.; Kennedy, M.; Barrowcliffe, A. An investigation into prescribing errors made by independent pharmacist prescribers and medical prescribers at a large acute NHS hospital trust: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, R.E.; John, D.N.; Deslandes, P.N. An exploratory study of the patient experience of pharmacist supplementary prescribing in a secondary care mental health setting. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, E.; McLelland, R.; Rushworth, G.F.; Stewart, D.; Gibson-Smith, K.; MacLure, A.; Cunningham, S.; MacLure, K. An evaluation of mental health clinical pharmacist independent prescribers within general practice in remote and rural Scotland. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M.; Haas, M.; Larew, J.; DeJongh, B. Impact of a mental health clinical pharmacist on a primary care mental health integration team. Ment. Health Clin. 2017, 7, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S.; Rosen, A.; Aslani, P.; Whitehead, P.; Chen, T.F. Developing the role of pharmacists as members of community mental health teams: Perspectives of pharmacists and mental health professionals. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 2007, 3, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finley, P.R.; Crismon, M.L.; Rush, A.J. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. New Ways of Working for Psychiatrists: Enhancing Effective, Person-Centred Services through New Ways of Working in Multidisciplinary and Multi-Agency Context. Final Report. ‘But not the End of the Story’. 2005. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/reader/97904 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Gable, K.N.; Stunson, M.J. Clinical pharmacist interventions on an assertive community treatment team. Community Ment. Health J. 2010, 46, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, O.; Smith, K.; Marven, M.; Broughton, N.; Geddes, J.; Cipriani, A. How pharmacist prescribers can help meet the mental health consequences of COVID-19. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2020, 23, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.E.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Chen, T.F. A comprehensive review of the impact of clinical pharmacy services on patient outcomes in mental health. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhec, M.; Tement, V. Positive evidence for clinical pharmacist interventions during interdisciplinary rounding at a psychiatric hospital. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhec, M.; Bratoviƒá, N.; Mrhar, A. Impact of clinical pharmacist’s interventions on pharmacotherapy management in elderly patients on polypharmacy with mental health problems including quality of life: A prospective non-randomized study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuhec, M.; Pharm, M.; Gorenc, K. Positive impact of clinical pharmacist interventions on antipsychotic use in patients on excessive polypharmacy evidenced in a retrospective cohort study. Glob. Psychiatry 2020, 2, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Confederation. NHS Terms and Conditions of Service Handbook. 2022. Available online: https://www.nhsemployers.org/publications/tchandbook (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. The crucial role of pharmacists in mental health. Pharm. J. 2017, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Education England. Stepping Forward to 2020/21: The Mental Health Workforce Plan for England. 2017. Available online: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Stepping%20forward%20to%20202021%20-%20The%20mental%20health%20workforce%20plan%20for%20england.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- NHS England. NHS Operational Productivity: Unwarranted Variations—Mental Health Services. Community Health Services. 2018. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/20180524_NHS_operational_productivity_-_Unwarranted_variations_-_Mental_....pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for the Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists. 2021. Available online: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/standards-for-the-initial-education-and-training-of-pharmacists-january-2021.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Health Education England. Advanced Practice Mental Health Curriculum and Capabilities Framework. 2021. Available online: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/AP-MH%20Curriculum%20and%20Capabilities%20Framework%201.2.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Peay, J. Decisions and Dilemmas: Working with Mental Health Law; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, P. Mental Health: The New Law; Jordan Publishing Limited: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adam, B.; Keers, R.N. Exploring the Views of Healthcare Professionals Working in a Mental Health Trust on Pharmacists as Future Approved Clinicians. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040080

Adam B, Keers RN. Exploring the Views of Healthcare Professionals Working in a Mental Health Trust on Pharmacists as Future Approved Clinicians. Pharmacy. 2022; 10(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdam, Balazs, and Richard N. Keers. 2022. "Exploring the Views of Healthcare Professionals Working in a Mental Health Trust on Pharmacists as Future Approved Clinicians" Pharmacy 10, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040080

APA StyleAdam, B., & Keers, R. N. (2022). Exploring the Views of Healthcare Professionals Working in a Mental Health Trust on Pharmacists as Future Approved Clinicians. Pharmacy, 10(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040080