Clinical Impact of Implementing a Nurse-Led Adverse Drug Reaction Profile in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medicines in UK Primary Care: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

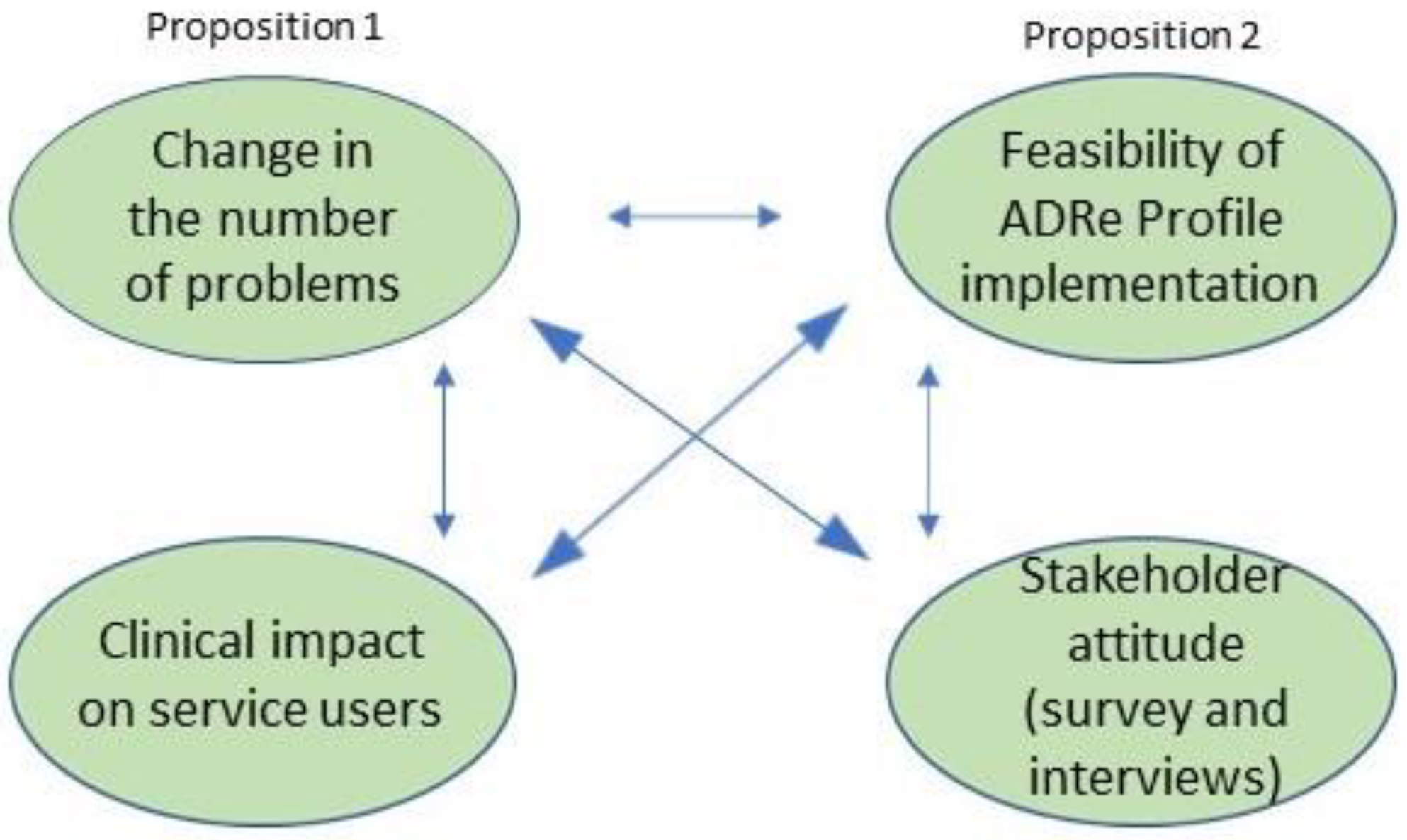

2. Materials and Methods

Design

3. Phase One: Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial

3.1. Participants

- Age ≥ 65 years;

- At least one long-term medicated condition;

- Prescribed ≥ 5 medications daily (vitamin and nutritional supplements and moisturising skin preparations will not be counted as ‘medicines’ for the purpose of this trial);

- Willing and able to give informed, signed consent themselves;

- Patients who, in the opinion of their nurses, lack capacity will be included if a consultee/representative is available and willing to confer with the patient and give consent on their behalf—a consultee may be a relative or friend who cares for the individual lacking capacity, but not professionally/for payment [45].

- Unable to consent and no consultee/representative available;

- Not fluent in English or Welsh (unless a family member can assist with translation)

- Receiving end-of-life care—the patient safety criteria and goals of care for patients at the end of life may be different to those of general populations [46] and specialist skills are needed to address these different challenges;

- Not expected to remain in the practice for the next 12 months

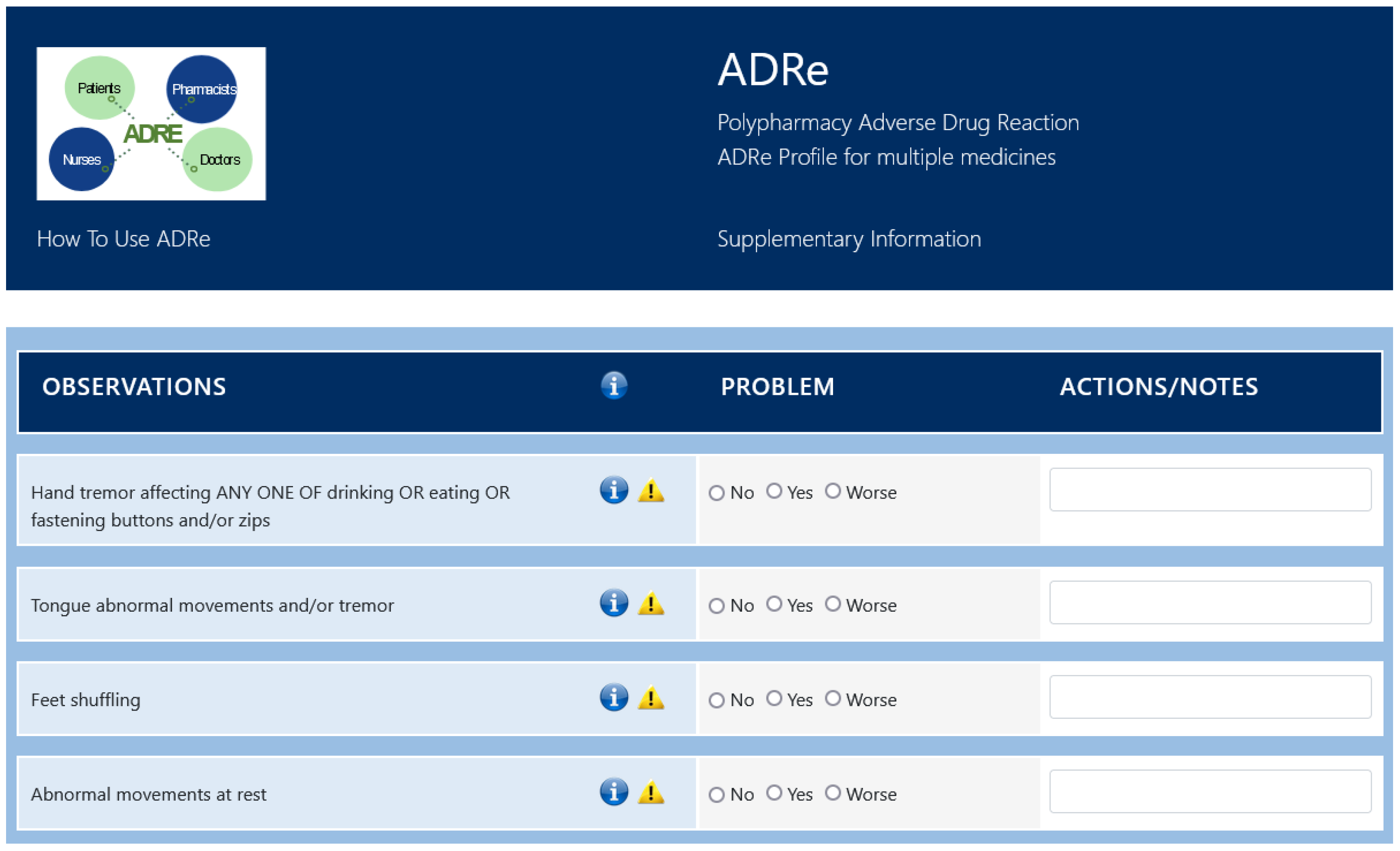

3.2. Intervention

3.3. Outcomes

- Clinical impact on patients

- New problems identified not recorded in GP notes (number and nature);

- Problems addressed (number and nature);

- Number of patients with a change in signs and symptoms potentially related to prescribed medicines (calculated as a difference between first and second ADRe Profile responses for each patient).

- Outcomes related to understanding the process of ADR management in primary care:

- Number and nature of items on the ADRe Profile that can be populated from accessing the GP nursing and medical notes;

- Prescription changes (number of patients with changes in prescription regimens: drug or dose, number and nature of changes);

- Description of stakeholder views on ADRe Profile implementation effectiveness (survey rating of the ADRe Profile-Likert scale);

- Description of stakeholder views on ADRe Profile implementation feasibility (eliciting interview themes).

- The secondary objective is to estimate costs associated with ADRe implementation, and the associated secondary outcome measures are:

- Survey of the average nurses’, assistants’, doctors’ and pharmacists’ time to complete and/or action one ADRe Profile, as mean and median length of health professionals’ time spent with one ADRe Profile.

- Estimation of the cost of nurses’, GP’s and pharmacists’ time based on average national salary cost per hour [48].

- Description of the main stakeholders’ views on multidisciplinary collaboration (eliciting interview themes).

- Description of the patients’ views on the contribution of ADRe Profile to patient-centred care (eliciting interview themes).

3.4. List of Variables

- Age;

- Sex as m/f;

- Number, doses and formulations of medicines (prescribed and bought over the counter);

- High doses of any medicine (maximum recommended therapeutic dose);

- Morbidities, as reported by Davies and colleagues [49];

- Post code of GP practice;

- Involvement of a consultee y/n.

3.5. Sample Size

3.6. Assignment of Interventions

3.7. Data Collection, Management and Analysis

3.8. Data Management

3.9. Statistical Methods

3.10. Data Monitoring

3.11. Criterion for Stopping This Study Early

3.12. Governance

3.13. Ancillary and Post-Trial Care

4. Phase Two: Stakeholder Views

5. Ethics and Dissemination

5.1. Consent

5.2. Confidentiality

5.3. Dissemination

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aronson, J.K.; Ferner, R.E. Clarification of Terminology in Drug Safety. Drug Saf. 2005, 28, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.A.; Camacho, E.; Jankovic, D.; Sculpher, M.J.; Faria, R. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2021, 30, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.; Prout, H.; Carter, N.; Dicomidis, J.; Hayes, J.; Round, J.; Carson-Stevens, A. Nobody ever questions-Polypharmacy in care homes: A mixed methods evaluation of a multidisciplinary medicines optimisation initiative. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. NICE Guideline 5. 2015. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Parekh, N.; Ali, K.; Page, A.; Roper, T.; Rajkumar, C. Incidence of Medication-Related Harm in Older Adults After Hospital Discharge: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. (JAGS) 2018, 66, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Foundation; Stafford, M.; Steventon, A.; Thorlby, R.; Fisher, R.; Turton, C.; Deenyhttps, S. Understanding the Health Care Needs for People with Multiple Health Care Conditions. 2018. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/understanding-the-health-care-needs-of-people-with-multiple-health-conditions (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Office for National Statistics. People with Long-Term Health Conditions, UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/adhocs/11478peoplewithlongtermhealthconditionsukjanuarytodecember2019 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- World Health Organisation. Medication without Harm. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255263/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.6-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Aronson, J.K. Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs: The International Encyclopedia of Adverse Drug Reactions and Interactions, 16th ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dücker, C.M.; Brockmöller, J. Genomic Variation and Pharmacokinetics in Old Age: A Quantitative Review of Age- vs. Genotype-Related Differences. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 105, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kneller, L.A.; Hempel, G. Modelling Age-Related Changes in the Pharmacokinetics of Risperidone and 9-Hydroxyrisperidone in Different CYP2D6 Phenotypes Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Approach. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Carstens, N.; Kvinge, L.; Fjell, A.; Wennersberg, M.; Folleso, K.; Skaug, K.; Seiger, A.; Cronfalk, B.S.; Bostrom, A.-M. Polypharmacy and potential drug–drug interactions in home-dwelling older people—A cross-sectional study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, P.H.; da Cruz, D.T.; Lucchetti, A.L.G.; Leite, I.C.G.; Lucchetti, G. The “iatrogenic triad”: Polypharmacy, drug–drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiris, M.A.; Sawan, M.; Hilmer, S.N.; Awadalla, R.; Gnjidic, D. Prevalence of adverse drug events and adverse drug reactions in hospital among older patients with dementia: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insani, W.N.; Whittlesea, C.; Alwafi, H.; Man, K.K.; Chapman, S.; Wei, L. Prevalence of adverse drug reactions in the primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Medication Safety in Polypharmacy: Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325454 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Duerden, M.; Avery, T.; Payne, R. Polypharmacy and Medicines Optimisation. Making It Safe and Sound. The King’s Fund. 2013. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines Optimisation: Helping Patients to Make the Most of Medicines. 2013. Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses. 2018. Available online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards-of-proficiency/nurses/future-nurse-proficiencies.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. A Competency Framework for all Prescribers; RPS: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Professional%20standards/Prescribing%20competency%20framework/prescribing-competency-framework.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Rankin, A.; Cadogan, C.A.; Patterson, S.M.; Kerse, N.; Cardwell, C.R.; Bradley, M.C.; Ryan, C.; Hughes, C. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD008165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ni, X.-F.; Yang, C.-S.; Bai, Y.-M.; Hu, Z.-X.; Zhang, L.-L. Drug-Related Problems of Patients in Primary Health Care Institutions: A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 698907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, A.C.M.; Zwart, D.L.M.; Poldervaart, J.M.; de Gier, J.J.; de Wit, N.J.; de Bont, A.A.; Bouvy, M.L. Non-dispensing pharmacists’ actions and solutions of drug therapy problems among elderly polypharmacy patients in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2019, 36, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokanovic, N.; Tan, E.C.; Sudhakaran, S.; Kirkpatrick, C.M.; Dooley, M.J.; Ryan-Atwood, T.E.; Bell, J.S. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: An overview of systematic reviews. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 661–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, G.H.; Keers, R.N.; Ashcroft, D.M. Frequency and Nature of Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events in Mental Health Hospitals: A Systematic Review. Drug Saf. 2017, 40, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdot, S.; Roudot, M.; Schramm, C.; Katsahian, S.; Durieux, P.; Sabatier, B. Interventions to reduce nurses’ medication administration errors in inpatient settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, T.; Seyedfatemi, N.; Mirzaee, M.S.; Maleki, M.; Mardani, A. Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice in Relation to Pharmacovigilance and Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6630404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S. Managing adverse drug reactions: An orphan task. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 38, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baetselier, E.; Van Rompaey, B.; Batalha, L.M.; Bergqvist, M.; Czarkowska-Paczek, B.; De Santis, A.; Dijkstra, N.E.; Fernandes, M.I.; Filov, I.; Grøndahl, V.A.; et al. EUPRON: Nurses’ practice in interprofessional pharmaceutical care in Europe. A cross-sectional survey in 17 countries. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaya, A.; Konlan, K.D.; Kim Do, H. Improving patient safety through identifying barriers to reporting medication administration errors among nurses: An integrative review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swansea University. The ADRe Profile. 2018. Available online: https://www.swansea.ac.uk/adre/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Jones, R.; Moyle, C.; Jordan, S. Nurse-led medicines monitoring: A study examining the effects of the West Wales Adverse Drug Reaction Profile. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 31, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.; Gabe, M.; Newson, L.; Snelgrove, S.; Panes, G.; Picek, A.; Russell, I.T.; Dennis, M. Medication Monitoring for People with Dementia in Care Homes: The Feasibility and Clinical Impact of Nurse-Led Monitoring. Sci. World 2014, 2014, 843621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.; Gabe-Walters, M.E.; Watkins, A.; Humphreys, I.; Newson, L.; Snelgrove, S.; Dennis, M.S. Nurse-Led Medicines’ Monitoring for Patients with Dementia in Care Homes: A Pragmatic Cohort Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jordan, S.; Banner, T.; Gabe-Walters, M.; Mikhail, J.M.; Panes, G.; Round, J.; Snelgrove, S.; Storey, M.; Hughes, D. Nurse-led medicines’ monitoring in care homes, implementing the Adverse Drug Reaction (ADRe) Profile improvement initiative for mental health medicines: An observational and interview study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Hardy, B.; Coleman, M. Medication management: An exploratory study into the role of Community Mental Health Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 29, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Knight, J.; Pointon, D. Monitoring Adverse Drug Reactions: Scales, Profiles and Checklists. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2004, 51, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: Gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol. Assess 2021, 25, 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G.; Mann, H.; Berlin, J.A.; Dickersin, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Schulz, K.F.; Parulekar, W.R.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013, 346, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Östlund, U.; Kidd, L.; Wengström, Y.; Rowa-Dewar, N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bharmal, M.; Guillemin, I.; Marrel, A.; Arnould, B.; Lambert, J.; Hennessy, M.; Fofana, F. How to address the challenges of evaluating treatment benefits-risks in rare diseases? A convergent mixed methods approach applied within a Merkel cell carcinoma phase 2 clinical trial. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, C.; Ellefsen, B. The value of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in nursing research by means of method triangulation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.K.; Elbourne, D.R.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004, 328, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Department of Health. Mental Capacity Act; HMSO: London, UK, 2005. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Akdeniz, M.; Yardımcı, B.; Kavukcu, E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211000918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.; Banner, T.; Gabe-Walters, M.; Mikhail, J.M.; Round, J.; Snelgrove, S.; Storey, M.; Wilson, D.; Hughes, D. Nurse-led medicines’ monitoring in care homes study protocol: A process evaluation of the impact and sustainability of the adverse drug reaction (ADRe) profile for mental health medicines. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSR). Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/unit-costs-2020/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Davies, L.E.; Spiers, G.; Kingston, A.; Todd, A.; Adamson, J.; Hanratty, B. Adverse Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Older People: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uitenbroek, D.G. Correlation: SISA Home. 1997. Available online: http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Cornfield, J. Randomization by group: A formal analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1978, 108, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killip, S.; Mahfoud, Z.; Pearce, K. What is an intracluster correlation coefficient? Crucial concepts for primary care researchers. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 9th ed.; International Edition; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hemming, K.; Girling, A. Cluster randomised trials: Useful for interventions delivered to groups: Study design: Cluster randomised trials. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 28.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021; Released. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer, S.; Torgerson, D.; Watson, J. Evidence for risk of bias in cluster randomised trials: Review of recent trials published in three general medical journals. BMJ 2003, 327, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez, D.; Van der Stuyft, P.; Zabala, M.C.; Castro, M.; Lefèvre, P. A modified theoretical framework to assess implementation fidelity of adaptive public health interventions. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carroll, C.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.; Booth, A.; Rick, J.; Balain, S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Health Service. National Tariff Payment System. 2021. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/21-22-National-tariff-payment-system.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Santana, M.J.; Ahmed, S.; Lorenzetti, D.; Jolley, R.J.; Manalili, K.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. Measuring patient-centred system performance: A scoping review of patient-centred care quality indicators. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.A. Some practical aspects of qualitative data analysis: One way of organising the cognitive processes associated with the generation of grounded theory. Qual. Quant. 2006, 15, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillemor, R.-M.; Hallberg. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2006, 1, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L.L. Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. A Practical Introduction to in-Depth Interviewing; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, C.; Patel, S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elderidge, S.; Campbell, M.K.; Campbell, M.K.; Drahota, A.; Giraudeau, B.; Reeves, B.; Siegfried, N.; Higgins, J. Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2). Additional Considerations for Cluster-Randomized Trials (RoB 2 CRT). 2021. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yDQtDkrp68_8kJiIUdbongK99sx7RFI-/view (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Logan, V.; Bamsey, A.; Carter, N.; Hughes, D.; Turner, A.; Jordan, S. Clinical Impact of Implementing a Nurse-Led Adverse Drug Reaction Profile in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medicines in UK Primary Care: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030052

Logan V, Bamsey A, Carter N, Hughes D, Turner A, Jordan S. Clinical Impact of Implementing a Nurse-Led Adverse Drug Reaction Profile in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medicines in UK Primary Care: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Pharmacy. 2022; 10(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLogan, Vera, Alexander Bamsey, Neil Carter, David Hughes, Adam Turner, and Sue Jordan. 2022. "Clinical Impact of Implementing a Nurse-Led Adverse Drug Reaction Profile in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medicines in UK Primary Care: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial" Pharmacy 10, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030052

APA StyleLogan, V., Bamsey, A., Carter, N., Hughes, D., Turner, A., & Jordan, S. (2022). Clinical Impact of Implementing a Nurse-Led Adverse Drug Reaction Profile in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medicines in UK Primary Care: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Pharmacy, 10(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030052